Significance

Heterosis provides an important strategy for increasing crop yield, and breeding and adoption of hybrid crops is a feasible way to increase crop yields. Male sterility is an essential trait in hybrid seed production for monoclinous crops, including wheat. Heterosis in wheat was observed approximately 100 y ago. However, very little commercial hybrid wheat is planted in the world because of the lack of a suitable male sterility trait. Therefore, understanding the molecular nature of male fertility in wheat is critical for hybrid wheat development. Here, we report the cloning and molecular, biochemical, and cell-biological characterizations of Male Sterility 1 (Ms1) in bread wheat, and provide a foundation for large-scale commercial hybrid wheat breeding and hybrid seed production.

Keywords: Male Sterility 1, epigenetic silence, phospholipid binding, wheat, hybrid seed production

Abstract

Male sterility is an essential trait in hybrid seed production for monoclinous crops, including rice and wheat. However, compared with the high percentage of hybrid rice planted in the world, little commercial hybrid wheat is planted globally as a result of the lack of a suitable system for male sterility. Therefore, understanding the molecular nature of male fertility in wheat is critical for commercially viable hybrid wheat. Here, we report the cloning and characterization of Male Sterility 1 (Ms1) in bread wheat by using a combination of advanced genomic approaches. MS1 is a newly evolved gene in the Poaceae that is specifically expressed in microsporocytes, and is essential for microgametogenesis. Orthologs of Ms1 are expressed in diploid and allotetraploid ancestral species. Orthologs of Ms1 are epigenetically silenced in the A and D subgenomes of allohexaploid wheat; only Ms1 from the B subgenome is expressed. The encoded protein, Ms1, is localized to plastid and mitochondrial membranes, where it exhibits phospholipid-binding activity. These findings provide a foundation for the development of commercially viable hybrid wheat.

Wheat is an important staple food crop worldwide; it constitutes approximately 20% of the calories consumed by humans and serves as the major food source for 30% of the world’s population. Global wheat grain yields increased in the 1960s and 1970s as new varieties with mutations in the “green revolution” gene, a GAI ortholog in wheat, were adopted (1, 2). However, to meet the demand of an increasing global population for a high-quality food supply, a substantial increase in wheat grain yield is vital (3, 4). Thus, a new green revolution in wheat is necessary.

Hybrid vigor is an important consideration in increasing crop yields. The breeding and large-scale adoption of hybrid rice and corn have contributed significantly to the global food supply, indicating that the use of hybrid crops is a feasible means of increasing crop yields (5, 6). However, hybrid wheat currently accounts for less than 0.2% of the total planted wheat acreage around the world despite several decades of development (7, 8). The lack of commercial progress in hybrid wheat is the result of a lack of a practical male sterility trait, which is essential for hybrid seed production by monoclinous crops (9, 10). Therefore, identifying a nuclear recessive male sterility trait and its corresponding gene in wheat is a prerequisite for commercial hybrid wheat breeding and hybrid seed production (11), which has been demonstrated in maize (12, 13) and rice, another monoclinous crop (5, 6). Among the five stable genic male sterility (GMS) loci (MS1–MS5) identified thus far in bread wheat (14–18), ms1 and ms5 are recessive mutants (16, 19), whereas Ms2, Ms3, and Ms4 are dominant mutants (20–22). Presently, only one dominant gene, Ms2, has been cloned (23, 24). Ms2 mutants have been widely used for wheat breeding and potentially for hybrid wheat breeding (23). However, to date, recessive nuclear genes affecting male fertility have not been cloned, even though mutants were identified almost 60 y ago.

Here, we report the cloning and molecular, biochemical, and cell-biological characterization of a nuclear recessive locus, MS1, in allohexaploid bread wheat. We developed a strategy for cloning wheat genes, MutMap-based cloning, by combining MutMap (25) and traditional map-based cloning approaches. MS1 is a newly evolved gene that exists only in the Poaceae. It is specifically expressed in microsporocytes, with ortholog sister genes that are epigenetically silenced in the A and D subgenomes of allohexaploid wheat. Our work details a nuclear-recessive gene that regulates male fertility in hexaploid wheat and provides a foundation for large-scale commercial hybrid wheat breeding and hybrid seed production.

Results

Ms1 Is Required for Microgametogenesis in Wheat.

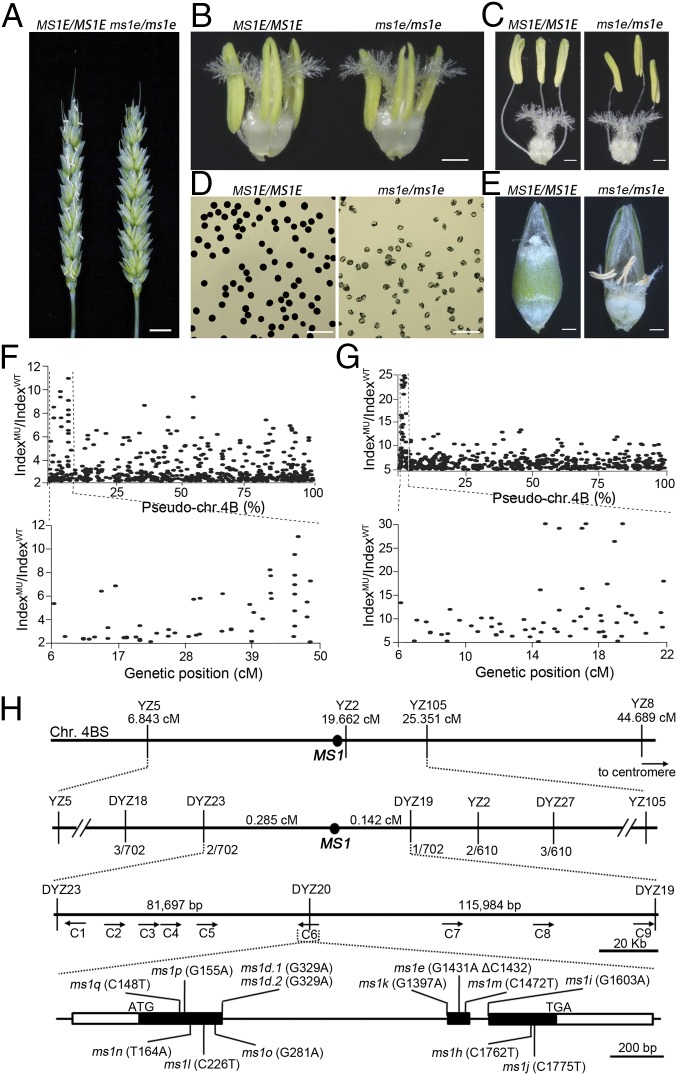

Unlike WT plants, ms1e plants lack extruded anthers and the glumes remain open at anthesis (Fig. 1A). There is no obvious difference in pistil development between WT and ms1e plants (Fig. 1 B and C); however, ms1e anthers are slightly smaller and indehiscent. Further, ms1e anthers bear aborted pollen, leading to unfertilized pistils and complete sterility (Fig. 1 C–E). To examine the role of Ms1 in pollen development, we analyzed microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in WT and ms1e plants by using DAPI staining and histological sections. No difference in pollen development was observed up to the early uninuclear stage of microsporogenesis between WT and ms1e plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A); approximately 14% of ms1e pollen grains had become shrunken with a condensed nucleus at the late unicellular stage. No normal binucleate or trinucleate pollen grains developed in ms1e (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), suggesting a defect during microgametogenesis. However, no defects were observed in the surrounding somatic cell layers in ms1e compared with WT, including defects in the tapetal layer (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). These data suggest that Ms1 is required for microgametogenesis in wheat.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic characterization of ms1 and the MutMap-based cloning of Ms1 from hexaploid wheat. (A) Spikes of Ms1 and ms1e. (Scale bar: 1 cm.) Anthers of Ms1 and ms1e before (B) and after filament elongation (C). (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (D) Mature pollen grains of Ms1 and ms1e stained with I2-KI. (Scale bar: 200 μm.) (E) Seeds of Ms1 and ms1e at 20 d after pollination. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) Scatter diagrams of SNPs between Ms1 and ms1e plants obtained from RNA-seq (F) and DNA-seq (G) by MutMap analysis. The y axis shows the indexMU/indexWT ratios [index = Nmutant/(Nreference + Nmutant), N represents the number of accumulated reads with corresponding genotypes], and the x axis presents the relative physical (Upper) and genetic (Lower) positions of each SNP on chromosome 4B (Chr. 4B) (31). (H) Map-based cloning of Ms1 using SNP markers. (Top) Genetic map of the Ms1 region on chromosome 4BS based on SNP markers obtained from RNA-seq data. The SNP markers and their corresponding genetic positions are indicated. (Middle) Fine mapping of the Ms1 region on chromosome 4BS based on the SNP markers obtained from the DNA-seq data. The numbers beneath the line in the second panel indicate the recombination frequency. (Bottom) Genetic structure of Ms1 and ms1 allele characterization. Closed boxes represent exons; connecting lines represent introns. ATG and TGA are indicated, and the mutation for each of 13 alleles is indicated. The mutation site in each allele is based on the sequence in the variety from which the allele is generated.

MutMap-Based Cloning of Ms1 in Bread Wheat.

Ms1 was formerly mapped to a region encompassing the distal 16% of the short arm of chromosome 4B (4BS) (26). In our study, we used a modified version of the MutMap approach (25) to clone Ms1. First, we used transcriptome sequence (i.e., RNA-seq) data from three Ms1 genotypes—Ms1/Ms1, Ms1/ms1e, and ms1e/ms1e—segregated from the progeny of heterozygous ms1e plants (SI Appendix, Table S1). As ms1e was recovered from an EMS-mutagenized population of WT Chris (19, 27), it was expected to carry a point mutation in Ms1. Through an alignment of the reads to predicted genes (28) and mapping to chromosome 4B (29), SNPs between the expressed genes from Ms1/Ms1 and ms1e/ms1e were found to be concentrated in an ∼50-cM region of chromosome 4BS (Fig. 1F), consistent with the notion that Ms1 is located in this region. However, the huge and highly similar three bread wheat subgenomes made it difficult to identify the SNP responsible for the mutation in Ms1. Therefore, instead of identifying Ms1 from those SNP-containing genes, we used the SNPs as markers to further map Ms1 by using 676 progeny of heterozygous ms1e plants. In this way, we narrowed down Ms1 to a 12.82-cM interval in chromosome 4BS (Fig. 1 F and H and SI Appendix, Table S2).

As the SNP markers from the RNA-seq data were not sufficiently dense to narrow the region containing Ms1, we resequenced the genomes of the Ms1/Ms1 and ms1/ms1 genotypes segregated from the progeny of the ms1e heterozygotes (SI Appendix, Table S3) to generate additional SNP markers for fine mapping (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Table S2). Eventually, we mapped Ms1 to a 198-kb interval by using the SNP markers generated from our DNA-seq data (Fig. 1 G and H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Nine predicted genes were located within this region (SI Appendix, Table S4).

To identify the gene responsible for the ms1 phenotypes from these candidates, we took advantage of three reported ms1 alleles as well as 11 newly recovered ms1 alleles from our EMS-mutagenized population of Chinese bread wheat (variety “Ningchun 4”; SI Appendix, Table S5). Sequencing revealed mutations or deletions for each of the 14 ms1 alleles in candidate gene 6 (C6; Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Table S5), indicating that C6 was Ms1. To confirm this, we transferred a genomic DNA fragment containing full-length C6 into immature embryos that are homozygous for the ms1e allele. The genomic fragment completely complemented the abnormal spike and pollen developmental phenotypes of the mutant, and it restored male fertility (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, C6 was confirmed to be Ms1 from the hexaploid bread wheat genome.

MS1 Is a Newly Evolved Gene in the Poaceae Family.

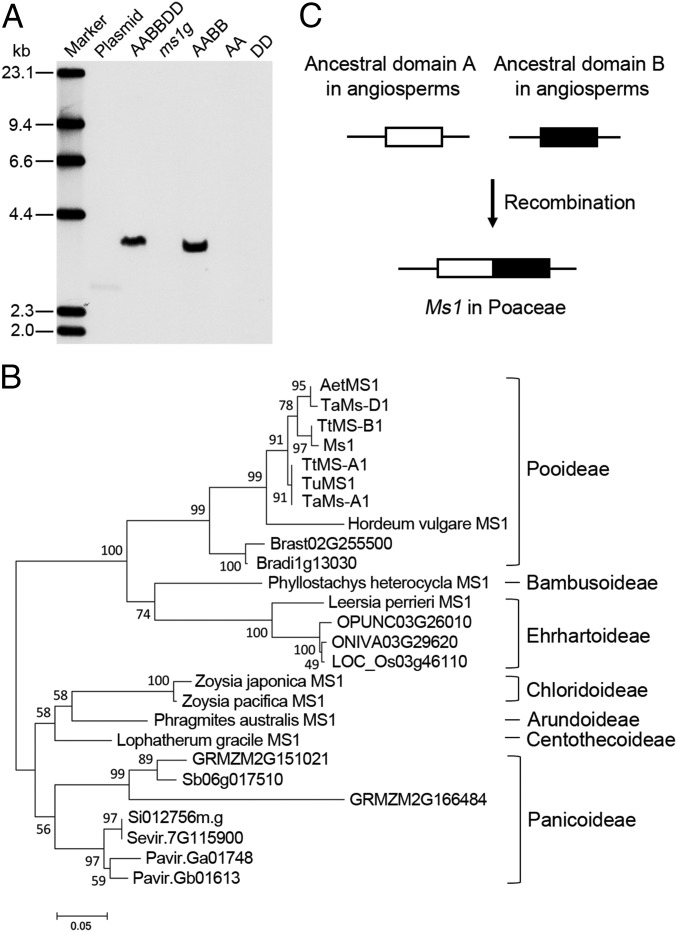

To determine the genomic structure of Ms1, we performed Southern blotting by using probes specific for Ms1. One Ms1 was detected in the hexaploid bread wheat genome, from the B subgenome; no Ms1 was detected in Triticum urartu (AA) or Aegilops tauschii (DD), and only one Ms1 was detected in allohexaploid wheat or Triticum turgidum (an allotetraploid; AABB; Fig. 2A). Moreover, no Ms1 was detected in ms1g, indicating that the Ms1 region used as the probe was deleted in ms1g (Fig. 2A). A BLAST analysis using Ms1 revealed two Ms1-related genes from the A and D subgenomes, respectively, of the hexaploid wheat genome, with DNA sequence identities of 82.9% and 83.9% between Ms1 and Ms-A1 and between Ms1 and Ms-D1, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Ms1 orthologs were identified only in the Poaceae, including all seven subfamilies for which the sequence of MS1 was available (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Table S6). No full-length Ms1 homolog was identified from other families, but sequences corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ portions of Ms1, respectively, were identified across angiosperms (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Tables S7 and S8). These results suggest that MS1 is a newly evolved gene within the Poaceae lineage, but that it contains two conserved domains that arose independently in the ancestral angiosperm lineages.

Fig. 2.

Genomic structure of Ms1 in the genomes of hexaploid, tetraploid, and diploid wheat and the origination of MS1 in Poaceae. (A) Southern blot hybridization of Ms1 in hexaploid, tetraploid, and diploid wheat using Ms1-specific probes. Genomic DNA from AABBDD (Ms1/Ms1), ms1g, AABB (T. turgidum accession Langdon), AA (T. urartu accession G1812), and DD (Ae. tauschii accession AL8/78), respectively, was digested with HindIII. The size markers are from a λ-DNA-HindIII digest. (B) Phylogenetic tree of Ms1 and its orthologs in Poaceae plants. Proteins are named according to their species. The numbers at the nodes show bootstrap values obtained for 1,000 replicates. The accession number and species name for each gene are shown in SI Appendix, Table S6. (C) The origination of MS1 in the Poaceae family.

Ms1 Is Specifically Expressed in Microsporocytes and Its Orthologs Are Epigenetically Silenced in the A and D Subgenomes of Hexaploid Wheat.

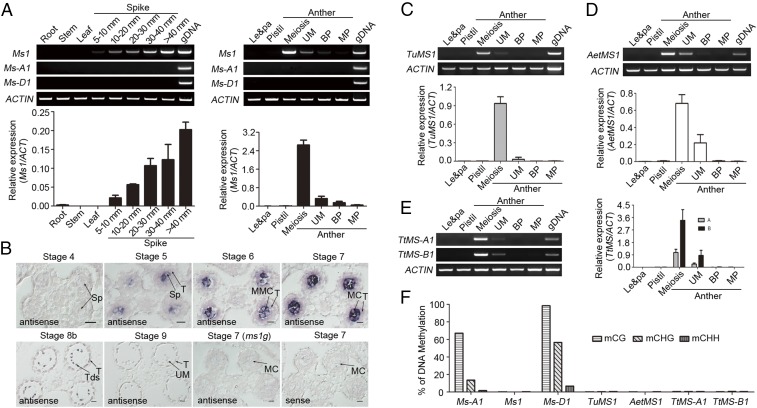

An RNA expression analysis indicated that Ms1 is not expressed in the roots, stems, or leaves of bread wheat; it is expressed only in the spikes. Further, it was highly expressed in developing anthers during microspore meiosis and detectable during the uninuclear stage of microgametogenesis, but it was not expressed in the lemma, palea, or pistil (Fig. 3A). The same expression pattern was observed for Ms1 protein in wheat anthers (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). In situ hybridization revealed that Ms1 was expressed in secondary sporogenous cells and highly expressed in microsporocytes, but not expressed in pollen grains during microgametogenesis (Fig. 3B). As a control, neither Ms1 mRNA nor Ms1 protein was expressed in ms1g (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B), consistent with the lack of Ms1 in the ms1g genome (Fig. 2A); this supports the conclusion that ms1g carries a deletion in the Ms1 region. These expression data suggest that Ms1 is expressed specifically in microsporocytes.

Fig. 3.

Ms1 expression pattern in wheat. Expression analysis of Ms1 by RT-PCR (A, C, D, Upper; and E, Left) and quantitative RT-PCR (A, C, D, Lower; and E, Right) in hexaploid T. aestivum (A), diploid T. urartu (C), diploid Ae. tauschii (D), and allotetraploid T. turgidum (E). BP, bicellular pollen stage; Le&pa, lemma and palea; MP, mature pollen stage; UM, unicellular microspore stage. ACTIN was used as an internal control. Error bars indicate the SD of three biological replicates. (B) In situ hybridization analysis of Ms1 in WT and ms1g anthers. MC, meiotic cell; MMC, microspore mother cell; SP, sporogenous cell; T, tapetum; Tds, tetrads. (F) DNA methylation analysis of the Ms1 promoter in the genomes of hexaploid, allotetraploid, and diploid wheat species.

Similar to most genes in the hexaploid wheat genome, Ms1 has orthologs, Ms-A1 and Ms-D1, in the A and D subgenomes, respectively, of hexaploid wheat (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Neither Ms-A1 expression nor Ms-D1 expression was detected in any of the tissues examined, including anthers, in which Ms1 is highly expressed (Fig. 3A). However, Ms1 orthologs from the genomes of diploid ancestral species of T. urartu (AA) and Ae. tauschii (DD) were expressed in anthers with a similar expression pattern to that of Ms1 in hexaploid wheat (Fig. 3 C and D). In addition, Ms1 orthologs from the A and B subgenomes were expressed in the anthers of allotetraploid T. turgidum (AABB), and their expression patterns were again similar to that of Ms1 in hexaploid wheat (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the transformation of Ms-A1 from T. aestivum into immature embryos homozygous for the ms1g allele completely rescued the abnormal phenotypes of the mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These data suggest that Ms-A1 is functional, similar to Ms1, but that Ms-A1 and Ms-D1 are silenced in hexaploid wheat.

To determine why Ms-A1 and Ms-D1 are silenced in hexaploid wheat, we examined the DNA methylation level in the promoter regions of Ms1, Ms-A1, and Ms-D1, and found that the promoters of Ms-A1 and Ms-D1 were hypermethylated at CG and CHG sites, whereas the Ms1 promoter was not (Fig. 3F). In addition, no obvious DNA methylation was detected in the promoters of the Ms1 orthologs in the genomes of T. urartu (AA), Ae. tauschii (DD), and allotetraploid T. turgidum (AABB; Fig. 3F). Together, our data indicate that Ms-A1 and Ms-D1 expression was epigenetically silenced during the generation and selection of allohexaploid wheat, and that only Ms1 from the B subgenome is expressed in the microsporocytes of allohexaploid wheat. Our data also demonstrate that epigenetic regulation underlies the asymmetric expression and subgenome dominance of Ms1 and its orthologs in hexaploid wheat.

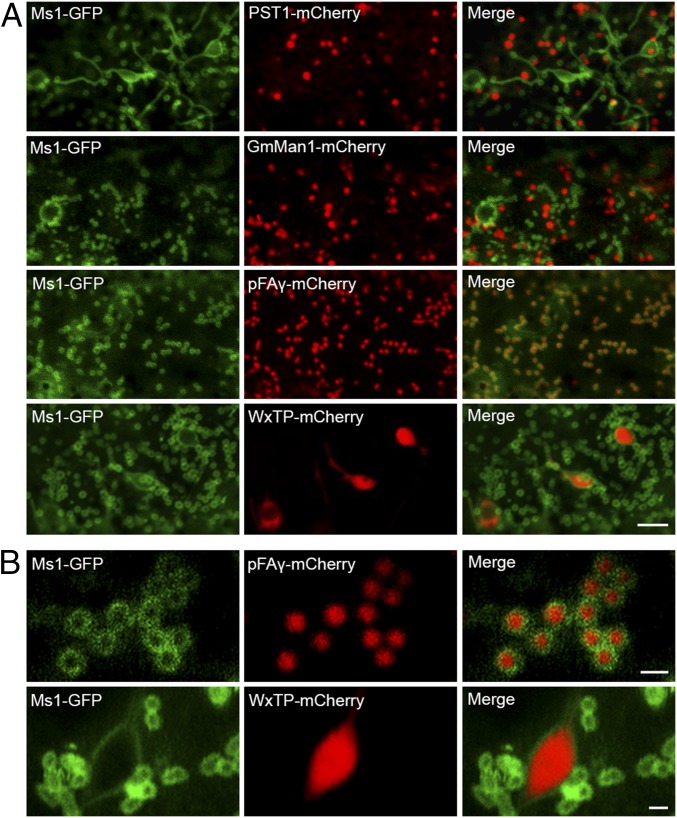

Ms1 Is Localized to the Membranes of Plastids and Mitochondria.

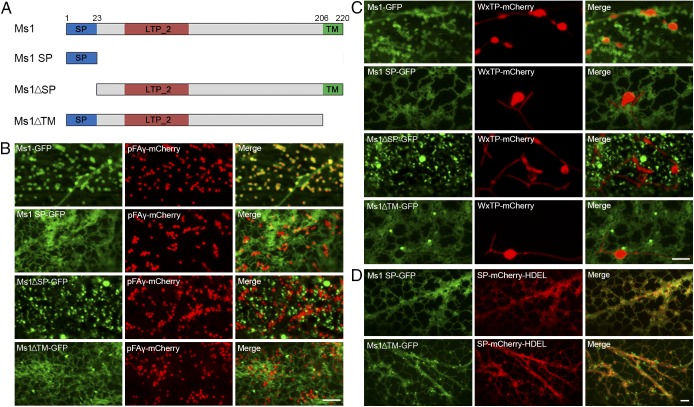

Ms1 encodes a protein containing 220 amino acids, with a predicted signal peptide between residues 1 and 23, and a predicted transmembrane domain between residues 206 and 220 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). However, Ms1 is not secreted from cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), indicating that it is a plasma or organelle membrane-localized protein. Ms1-GFP exhibited punctate and threadlike patterns in cells; it was neither colocalized with the peroxisome marker PST1 nor colocalized with the Golgi marker GmMan1, but it colocalized with the mitochondrial marker pFAγ. Ms1-GFP was also localized in plastid membranes; it was detected in rings around plastids as a result of colocalization between Ms1 and the plastid marker WxTP (Fig. 4A). Further analysis substantiated the localization of Ms1 in the plastid membrane and outer mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 4B). Deletion of the signal peptide or transmembrane domain of Ms1 disrupted its subcellular localization (Fig. 5 A–C), whereas the signal peptide domain of Ms1 alone localized the tagged protein to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; Fig. 5D). Additionally, truncated Ms1 lacking the transmembrane domain accumulated in the ER (Fig. 5D), indicating that the signal peptide domain of Ms1 is required for localization of the protein to the ER, whereas the transmembrane domain of Ms1 is required for integration into the plastid membrane and outer mitochondrial membrane from the ER, at least under its overexpression condition.

Fig. 4.

Subcellular localization of Ms1 and its colocalization with organelle markers. Onion epidermal cells were transiently cotransformed with constructs encoding Ms1-GFP and mCherry-fused organelle markers driven by the 35S promoter. GmMan1, Golgi marker; pFAγ, mitochondria marker; PST1, peroxisome marker; WxTP, plastid marker. (Scale bars: A, 5 µm; and B, 1 μm.)

Fig. 5.

The signal peptide and transmembrane domain of Ms1 are required for proper subcellular localization in plastids and mitochondria. (A) Schematic representations of the full-length and truncated Ms1 proteins used in our subcellular localization analysis. LTP_2, predicted LTP domain; SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane domain. (B–D) Colocalization of full-length or truncated Ms1 fused GFP with the mitochondrial marker pFAγ (B), plastid marker WxTP (C), or ER marker SP-mCherry-HDEL (D) in onion epidermal cells. (Scale bar: 5 μm.)

Ms1 Is a Phospholipid-Binding Protein.

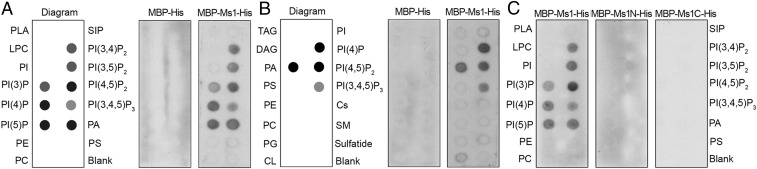

Besides the N-terminal signal peptide and C-terminal transmembrane domain, a lipid transfer protein (LTP) domain was predicted in Ms1 following the N-terminal signal peptide (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In plants, fatty acids are synthesized mainly in plastids and exported to the ER, where they are incorporated into phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylinositol-phosphates, and other membrane lipids (30). To determine whether Ms1 has lipid-binding activity, recombinant MBP-Ms1 was expressed in and purified from bacteria (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D) and then used to measure the binding activity of Ms1 to typical lipid constituents of plasma or organelle membranes. Ms1 bound PA and several phosphatidylinositols (PIs), including PI(3)P, PI(4)P, PI(5)P, PI(3,4)P, PI(3,5)P, PI(4,5)P, and PI(3,4,5)P (Fig. 6 A and B). However, no lipid-binding activity was detected for MBP (Fig. 6 B and C), indicating that Ms1 is a phospholipid-binding protein, especially for PA and PIs. In addition, neither N-terminal nor C-terminal portion of Ms1 bound lipids (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the whole Ms1 is required for its lipid binding activity. Therefore, Ms1 may transfer PA and PIs from the ER to plastids and mitochondria, and proper localization of PA and PIs is critical for microgametogenesis in wheat.

Fig. 6.

Ms1 binds phospholipids in vitro. Purified MBP-Ms1-His or MBP-His (A and B), MBP-Ms1N-His, and MBP-Ms1C-His (C) were overlaid in an Echelon P-6001 lipid strip (A and C) or Echelon P-6002 membrane strip (B). CL, cardiolipin; Cs, cholesterol; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; LPC, lysophosphocholine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PI(3)P, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate; PI(4)P, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate; PI(5)P, phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate; PI(3,4)P2, phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate; PI(3,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate; PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; PI(3,4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; TAG, triacylglycerol.

Discussion

Changes to the architecture of a gene and its encoded protein may give rise to new functions. We found that MS1 is a newly evolved gene that exists specifically in Poaceae plants; it was not found in ancestral or more recently evolved lineages other than Poaceae (Fig. 2B). Given that MS1 originated only in Poaceae, it may play an essential role in the development and survival of Poaceae plants. Indeed, Ms1 is essential for male fertility and metagenesis in bread wheat (Fig. 1A). Thus, it would be interesting to know whether MS1 plays a similar role in other Poaceae plants, especially rice and corn. Additionally, Ms1 contains two domains that are each conserved across angiosperms (Fig. 2C); the N terminus of Ms1 is predicted to contain an LTP domain, which is required for binding lipids (Fig. 6). However, compared with most plant LTPs (30), that of Ms1 is bigger (20 kDa compared with 7–10 kDa for most LTPs) as a result of the presence of the C terminus (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Thus, as new architectures arose in MS1 and its encoded protein during the evolution of Poaceae plants, new biochemical and biological functions were acquired. A point mutation in the C-terminal region of Ms1 (ms1j, S195F; Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Table S5) completely abolished the function of Ms1 in wheat, indicating that the C terminus of Ms1 is required for proper protein function. Further study is needed to reveal the role of the C-terminal portion of Ms1 in male fertility.

Heterosis in wheat was first reported approximately 100 y ago (31); since then, effort has been made to develop a hybrid wheat seed production system. Compared with its parents, the yield from hybrid wheat is as much as 30% greater (7, 8). Wheat is monoclinous and autogamous; therefore, the effort required for mechanical emasculation is prohibitive, and male sterility provides the best and most practical method for blocking self-fertilization during hybrid seed production. Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) was developed in 1951 by introducing Aegilops caudata cytoplasm into bread wheat (32); since then, cytoplasmically induced male sterile lines have been used as part of a three-line system for hybrid wheat seed production (27, 33). To date, more than 70 different male sterile cytoplasm systems have been reported in wheat (7). Chemically induced male sterility (using chemical hybridizing agents [CHAs]) has also been used to develop hybrid wheat systems (34); currently, more than 40 chemicals are available as potential CHAs (7, 8). The third approach used to develop hybrid wheat is the environmentally sensitive GMS-dependent two-line system (e.g., photoperiod- and temperature-induced GMS) (35, 36). However, the CMS system lacks effective fertility-restoring genes, CHA suffers from problems with toxicity and selectivity, and the photoperiod/thermosensitive system is not stable (7, 9, 37). These limitations have severely impeded the practicality of these systems for wheat hybrid seed production and may explain why only approximately 0.2% of all wheat acreage is currently hybrid wheat. However, the limitations inherent to these systems can be overcome by the use of a nonconditional GMS system (9, 12, 23), which was recently adapted for another monoclinous crop, rice (5). The basic requirements for a GMS system are corresponding mutations and nuclear genes controlling male sterility. In this study, we cloned a wheat nuclear-recessive gene affecting male sterility; therefore, our work has made it feasible to generate a stable and commercially viable hybrid seed production system in bread wheat.

Materials and Methods

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), diploid ancestral species of T. urartu and A. tauschii, and allotetraploid T. turgidum were used in this study. The mutants ms1d.1 and ms1e were obtained from the Wheat Genetics Resource Center at Kansas State University. We screened ms1d.2 and ms1h-p from an EMS-mutagenized population of bread wheat (variety Ningchun 4). Details of experimental procedures, such as cloning of Ms1, qPCR, in situ hybridization, Southern blot, Western blot, DNA methylation analysis, protein-lipid overlay assay, preparation of Ms1-specific antibodies, RNA-seq, resequencing and bioinformatics processing of the sequence data, microscopic analyses, and subcellular localization of Ms1, are described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jessica Habashi and Prof. Wenhua Zhang for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Transgenic Science and Technology Program of China Grant 2010ZX08010-003 (to X.W.D.) and in part by Beijing Municipal Government Science Foundation Grant CIT&TCD20150102 (to L.M.) and Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences, Peking University, (X.W.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (accession no. SRP113349).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1715570114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Peng J, et al. ‘Green revolution’ genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature. 1999;400:256–261. doi: 10.1038/22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pingali PL. Green revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12302–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912953109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilman D, Cassman KG, Matson PA, Naylor R, Polasky S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature. 2002;418:671–677. doi: 10.1038/nature01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley JA, et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature. 2011;478:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Z, et al. Construction of a male sterility system for hybrid rice breeding and seed production using a nuclear male sterility gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:14145–14150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613792113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng XW, et al. Hybrid rice breeding welcomes a new era of molecular crop design. Scientia Sinica Vitae. 2013;43:864–868. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh SK, Chatrath R, Mishra B. Perspective of hybrid wheat research: A review. Indian J Agric Sci. 2010;80:1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitford R, et al. Hybrid breeding in wheat: Technologies to improve hybrid wheat seed production. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:5411–5428. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Prat E, van Lookeren Campagne MM. Hybrid seed production and the challenge of propagating male-sterile plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longin CF, et al. Hybrid breeding in autogamous cereals. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1967-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh SP, Srivastava R, Kumar J. Male sterility systems in wheat and opportunities for hybrid wheat development. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015;37:1713. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Albertsen MC, et al.; inventors (2006) Nucleotide sequences mediating plant male fertility and method of using same. US Patent US WO2007002267.

- 13.Wu Y, et al. Development of a novel recessive genetic male sterility system for hybrid seed production in maize and other cross-pollinating crops. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:1046–1054. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugsleay T, Oram RN. Genic male sterility in wheat. Aust Plant Breed Genet Newsletter. 1959;14:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fossati A, Ingold M. A male sterile mutant in Triticum aestivum. Wheat Inf Serv (Kyoto) 1970;30:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasakuma T, Maan SS, Williams ND. EMS-induced male-sterile mutants in euplasmic and alloplasmic common wheat. Crop Sci. 1978;18:850–853. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driscoll CJ. Registration of Cornerstone male-sterile wheat germplasm. Crop Sci. 1977;17:190. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou K, Wang S, Feng Y, Ji W, Wang G. A new male sterile mutant LZ in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Euphytica. 2008;159:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klindworth DL, Williams ND, Maan SS. Chromosomal location of genetic male sterility genes in four mutants of hexaploid wheat. Crop Sci. 2002;42:1447–1450. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maan SS, Carlson KM, Williams ND, Yang T. Chromosomal arm location and gene centromere distance of a dominant gene for male sterility in wheat. Crop Sci. 1987;27:494–500. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maan SS, Kianian SF. Third dominant male sterility gene in common wheat. Wheat Inf Serv. 2001;93:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi LL, Gill BS. High-density physical maps reveal that the dominant male-sterile gene Ms3 is located in a genomic region of low recombination in wheat and is not amenable to map-based cloning. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103:998–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni F, et al. Wheat Ms2 encodes for an orphan protein that confers male sterility in grass species. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15121. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia C, et al. A TRIM insertion in the promoter of Ms2 causes male sterility in wheat. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15407. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe A, et al. Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using MutMap. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:174–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endo TR, Mukai Y, Yamamoto M, Gill BS. Physical mapping of a male-fertility gene of common wheat. Jpn J Genet. 1991;66:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franckowiak JD, Maan SS, Williams ND. A proposal for hybrid wheat utilizing Aegilops squarrosa L. cytoplasm. Crop Sci. 1976;16:725–728. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science. 2014;345:1251788. doi: 10.1126/science.1251788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman JA, et al. A whole-genome shotgun approach for assembling and anchoring the hexaploid bread wheat genome. Genome Biol. 2015;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benning C. Mechanisms of lipid transport involved in organelle biogenesis in plant cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:71–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman GF. Heredity of quantitative characters in wheat. Genetics. 1919;4:1–93. doi: 10.1093/genetics/4.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kihara H. Substitution of nucleus and its effects on genome manifestations. Cytologia (Tokyo) 1951;16:177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson JA. Hybrid wheat breeding and commercial seed development. Plant Breed Rev. 1984;2:303–319. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore RH. Several effects of maleic hydrazide on plants. Science. 1950;112:52–53. doi: 10.1126/science.112.2898.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murai K, Tsunewaki K. Photoperiod-sensitive cytoplasmic male sterility in wheat with Aegilops crassa cytoplasm. Euphytica. 1993;67:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian CM, Xu A, Uiang GH. Effects of low temperatures and genotypes on pollen development in wheat. Crop Sci. 1986;26:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen G, Gong D, Guo X, Qiu W, He Q. Problems of the hybrid with Chongqing thermo-photo-sensitive male sterility wheat C49S in the plain of Jiang Han. Mailei Zuowu Xuebao. 2005;25:147–148. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.