Abstract

The electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) has emerged as popular electronic nicotine delivery devices (ENDs). However, the general safety and validity of e-cigarettes for nicotine delivery efficacy are still not well understood. This study developed a new method for efficient measurement of nicotine levels in both the liquids (e-liquids) used in e-cigarettes and the aerosols generated from the e-cigarettes. Protonation of the pyrrolidine nitrogen of nicotine molecules by addition of excess hydrochloric acid affords an aminium salt that is readily quantified by Fourier transform ion cyclotron mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS). The kinetics of nicotine protonation was studied using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Quantitative analyses of nicotine in commercial e-liquids and in the corresponding derived e-cigarette aerosols were carried out using direct infusion FT-ICR-MS. The 1H NMR study of nicotine protonation revealed a first order reaction and an activation energy of 30.05 kJ mol−1. The nicotine levels measured in the commercial e-liquids were within a wide and highly variable range of −2.94% to +25.20% around the manufacturer’s stated values. The results indicated considerable differences between the measured levels and the advertised levels of nicotine in the e-liquids. The nicotine quantity measured in aerosols increased linearly both with nicotine level in e-liquids (same number of puffs) and with number of puffs (same e-liquids). These data show that quality control of e-liquids and use characteristics are major variables in efficacy of nicotine delivery.

TOC image

Analysis of nicotine in e-liquids and aerosols of e-cigarettes by protonation of nicotine in acidic solution and direct infusion into FT-ICR-MSMS.

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes are battery-powered, tobacco-free nicotine delivery devices. The devices aerosolize a nicotine-containing solution known as an e-liquid without combustion or smoke.1 An electronic cigarette device consists of three major parts: a rechargeable lithium ion battery, an atomizing unit where the e-liquid is heated and vaporized, and a cartridge that serves as a receptacle for the e-liquid.2 The e-liquid contains humectants (propylene glycol or glycerol or both), flavorings, and nicotine in varying amounts.3 The aerosol of electronic cigarettes simulates classic tobacco cigarette smoke in that the bulk of the aerosol is delivered to the user’s mouth and lung by inhalation after puffing.4

The use of electronic cigarettes is on a steady rise. In 2014, close to 4% U.S. adults and 16% of U.S. adult smokers used e-cigarettes. Experimentation with and use of e-cigarettes tripled among teenagers and youths from 2013–2014 — more youths now use electronic cigarettes than classic tobacco cigarettes.5 According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 2 million high school students and 450,000 middle school students currently use e-cigarettes.6,7

Nicotine is a toxic and potent alkaloid that is quickly absorbed through the skin and mucous membranes in its base form.8 It plays a significant role in the development of cardiovascular disease.9 Nicotine is known to constrict blood vessels and reduce the flow of blood to the hands and feet. In addition to its central nervous system effects, nicotine also inhibits the release of prostacyclin, a vasodilation prostaglandin, from vascular tissue and induces hormonal changes associated with hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA).10 The health effects, which are of major concern, include coronary artery and peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, peptic ulcer disease, and reproductive disorders.11 Nicotine has been implicated in stimulating neuroendocrine tumor cell line proliferation,12 a factor in the pathogenesis of lung cancer13 and apoptosis prevention.4 Also, the effects of nicotine are seen in every trimester of pregnancy, from increased spontaneous abortions in the first trimester to increased premature delivery rates and decreased birth weights in the final trimester.13 A lethal dose of nicotine in humans is 30–60 mg.14

Nicotine levels in e-liquids are intentionally formulated to create target strengths, yet measured levels may not match the manufacturer’s claim. There are a variety of e-liquids with different formula and nicotine strength (typically from 0 to 36 mg/mL). The efficacy of nicotine delivery by e-cigarettes is not well understood and there is a great variety of flavored e-liquids. Consequently, there is a great public health concern regarding exposure to harmful chemicals in aerosols of e-cigarettes.1–3,15 Therefore, there is a need for efficient measurement of nicotine in e-liquids and in aerosols of e-cigarettes and evaluation of the efficacy of nicotine delivery by ENDs.

The standard method for collection and analysis of nicotine in air (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, NIOSH 2551) requires a packed sorbent tube to trap nicotine by flowing air samples through the tube and using ethyl acetate to desorb nicotine from the sorbent for gas chromatography (GC) analysis. The method has issues including nicotine escaping from the sorbent tube during sample collection process and desorption efficiency of nicotine in solvents from the sorbent. The whole process is also time consuming and cumbersome. The analysis of nicotine in e-liquids by GC requires extraction of nicotine from the e-liquids using solvents such as ethyl acetate and toluene.16–17 Incomplete extraction causes great measurement errors. Recently, other methods were reported for collection of nicotine in the aerosols of e-cigarettes including flowing aerosols through filters or cold solvents.16–18 We describe here a novel method for effective measurement of trace nicotine in e-liquids and collecting nicotine in aerosols based on its protonation in acidic solution. Protonated nicotine in both e-liquids and as collected from derived aerosols facilitates effective and quantitative analysis by FT-ICR-MS.

Experimental

Materials

One popular electronic cigarette, blu plus® battery with two different flavored blu plus® cartridges (Classic Tobacco, Magnificent Menthol) was selected for this study. Ten popular e-liquids in the US market: three different flavored Halo e-liquids, two NJOY e-liquids, two VaporFi e-liquids with different levels of nicotine, an eVo Black diamond e-liquid, a Perfected Vapes e-liquid, and a Smooththol Nic Quid e-liquid were also purchased. Table 1 lists detailed information of these e-liquids and cartridges. 37% Hydrochloric acid, nicotine, and methanol were acquired from Sigma Aldrich. Deuterated nicotine was purchased from CDN Isotopes Inc. XRD-4 sorbent tubes for trapping nicotine were purchased from SKC company. The ultra-pure water used in this study was prepared using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Results of nicotine analysis from selected commercial e-liquids. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and the data is expressed as the average [±SD] of the measured values.

| EC code | Brand name | Model/Flavor | Country | Source of product | Vendor’s labeled nicotine (mg/mL) | Nicotine (mg/mL) measured | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL01 | EVO | Blackdiamond | USA | Kiosk | 6.00 | 6.28±0.17 | 4.67 |

| EL02 | NicQuid | Smooththol | USA | Kiosk | 6.00 | 6.54±0.41 | 9.00 |

| EL03 | PerfectedVapes | Clearwater | USA | Kiosk | 6.00 | 7.04±0.40 | 17.33 |

| EL04 | Halo | Menthol Ice | USA | Online | 6.00 | 6.53±0.20 | 8.83 |

| EL 05 | Halo | Mocha Café | USA | Online | 6.00 | 6.42±0.05 | 7.00 |

| EL06 | Halo | South Classic | USA | Online | 6.00 | 6.26±0.05 | 4.33 |

| EL07 | NJOY | Classic Tobacco | USA | Online | 10.00 | 12.25±0.53 | 25.20 |

| EL08 | NJOY | Classic Tobacco | USA | Online | 15.00 | 16.22±0.72 | 8.13 |

| EL09 | VaporFi | Classic Tobacco | USA | Online | 18.00 | 17.47±0.45 | −2.94 |

| EL10 | VaporFi | Classic Tobacco | USA | Online | 36.00 | 37.22±1.26 | 3.39 |

| ECC01 | Blu | Magnificent Menthol | USA | Online | 13–16 | 14.14±0.73 | 8.76 to − 11.63 |

| ECC02 | Blu | Classic Tobacco | USA | Online | 13–16 | 15.67±1.01 | 20.53 to −2.06 |

Measurement of nicotine by NMR Spectroscopy

To prepare a calibration curve for measurement of nicotine using 1H NMR spectroscopy, six solutions containing different amounts of nicotine dissolved in 400 μL DMSO-d6 were prepared. The concentrations of nicotine from solution 1 to solution 6 were set at 0.78, 1.56, 3.11, 7.78, 15.55, and 38.88 μmol•mL−1, respectively. Benzene was added to each solution as an internal reference at a concentration of 56.11 μmol/mL. 1H NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian 7600-AS instrument (400 MHz for 1H). The integration of the benzene hydrogen signal at δ 7.37 ppm was set at a constant 6, while the integrations of the nicotine hydrogens between δ 8.45–8.49 ppm were recorded.

Kinetics Measurement of nicotine protonation

A kinetics study on the protonation of nicotine (Scheme 1) was conducted by measuring the amount of nicotine at different reaction times at reaction temperatures of 0, 22, 40, and 60°C using 1H NMR. To a solution of nicotine (5.0 μL, 31.1 μmole) in water (291 μL) at a given temperature, 37% HCl (3.8 μL, 37.4 μmole) was added. The mixture was magnetically stirred for a specified time. The reaction was terminated at a set time by addition of ethyl acetate (400 μL) to extract any unprotonated nicotine. The organic layer then was separated from the aqueous layer with the aid of a pasture pipette and evaporated under vacuum. DMSO-d6 (400 μL) was added to the extracted neutral nicotine and the solution was analyzed by 1H NMR using benzene as the internal reference for quantification.

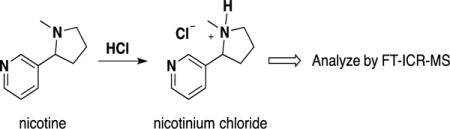

Scheme 1.

Protonation of nicotine and analysis of the salt form.

The first order reaction kinetics for nicotine protonation under the experimental conditions can be written as in equation 1,

| (1) |

where [nicotine] indicates the concentration of nicotine at t minutes and k is the apparent first order reaction rate coefficient. Integration of both sides of equation 1 and rearrangement affords equation 2,

| (2) |

where [nicotine]0 denotes the initial concentration of nicotine. Taking the natural logarithm of Arrhenius’ equation yields equation 3,

| (3) |

where Ea is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, T is the reaction temperature, and A is the pre-exponential factor.

Analysis of nicotine in e-liquids

Typically, 10 μL of each e-liquid was added to a solution of 37% HCl (5.0 μL, 49.2 μmole) in a mixture of MeOH (457.5μL) and water (37.5 μL) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for a minimum of 30 minutes to protonate nicotine. Then, 10 μL of the reaction solution was removed and directly analyzed, in triplicate, by FT-ICR-MS. The measured nicotine was expressed as the average [±SD] values.

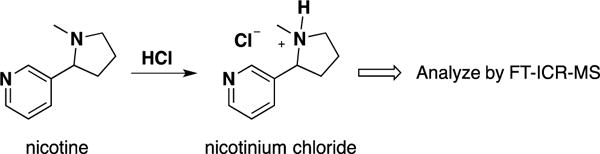

Collection and analysis of nicotine in e-cigarette aerosols

A software-controlled (FlexiWare) cigarette-smoking robot (CSR) (Sci-Req, Montreal, CAN) was used to generate aerosols from blu plus® electronic cigarette battery (fixed voltage 3.7V) with e-liquids in the refillable mystic® cartridges. The puffing topography of e-cigarette users has been intensively studied.19–20 The mean puff duration, puff flow rate, and puff volume varied significantly among the subjects.19 The puffing protocol in this work consisted of 4 seconds of puff durations, 91.1 mL of puff volumes, and 26 seconds of puff intervals to closely mirror typical puffing topography of e-cigarette users.19–20 Aerosols generated by the smoking robot flowed through a series of three impingers as shown in Figure 1 of the schematic diagram. Each impinger was charged with a solvent mixture of MeOH (91.5 mL), water (7.5 mL), and 37% HCl (1 mL). Initial experiments for collection of the aerosols with a series of four impingers indicated no nicotine in the fourth impinger. These experiments verified that the use of three impingers was sufficient for collection of all the aerosolized nicotine. After collection, 3 μL nicotinium-d3 was added to 500 μL of the solution from each impinger as an internal standard. The solution was then analyzed using FT-ICR-MS. To compare this collection of nicotine in aerosls with standard sorbent adsorption method (NIOSH 2551), nicotine in e-cigarette aerosols was also collected using XRD-4 sorbent tubes. NIOSH 2551 instruction was followed for collection of nicotine by the sorbent tubes, desorbing nicotine from the sorbent in ethyl acetate solution and analysis by GC-MS.

Figure 1.

The Schematic diagram of the inExpose Scireq smoking robot connected to the three impingers connected in series for trapping nicotine in aerosol of e-cigarettes.

FT-ICR-MS

An FT-ICR-MS instrument (Finnigan LTQ-FT, Thermo Electron, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a TriVersa NanoMate ion source (Advion BioSciences, Ithaca, NY) fitted with an electrospray chip (nozzle inner diameter 5.5 μm) was used for all mass spectrometric analyses. The TriVersa NanoMate was operated in positive ion mode by applying 2.0 kV with no head pressure. Initially, low-resolution MS scans were acquired for 1 min to ensure the stability of ionization, after which high mass accuracy data were collected using the FT-ICR analyzer, where MS scans were acquired for 5 min and at the target mass resolution of 100,000 at 200 m/z.

Results and discussion

Reaction kinetics of nicotine protonation

Based on pKb considerations, El Hellani et al21 reported that nicotine is predominantly present in free base form in both e-liquids and aerosols of electronic cigarettes. Nicotine in e-liquids was extracted using toluene and amenable to analysis by GC-MS. The hypothesis of this work is that protonation of nicotine in e-liquids using strong acid, such as hydrochloric acid, will form a nicotinium ion (Scheme 1) that can be readily measured by direct infusion FT-ICR-MS. We were gratified to learn that this approach is effective — the nicotinium cation was readily quantified using FT-ICR-MS. For more efficient extraction of free nicotine for NMR analysis, we chose ethyl acetate rather than toluene, as reported by El Hellani et al.21 Supplementary Fig. S1 shows a good linear dependence of n(nicotine)/n(benzene) on H(nicotine)/H(benzene), where n = moles and H = corresponding proton integration of NMR spectra. We used this plot as an NMR calibration curve to measure nicotine concentration in the following kinetics study of nicotine protonation.

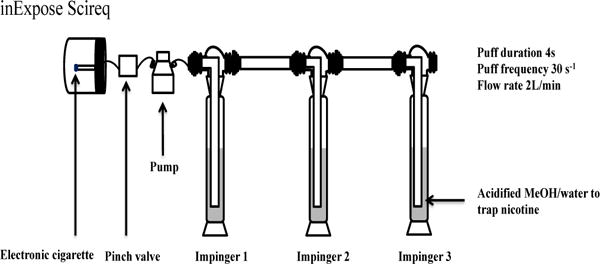

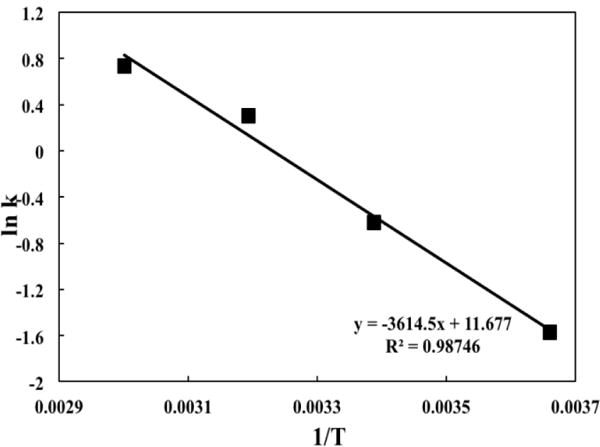

The 1H NMR spectra of 5μL pure nicotine added to 400 μL DMSO-d6 and the ethyl acetate extract in 400 μL DMSO-d6 obtained after reaction of 5μL pure nicotine with HCl in water for 30 min are compared in Supplementary Figure S2. More than 98% of nicotine was protonated and retained in the aqueous phase based on the NMR data of this experiment. To determine the reaction rates, protonation of nicotine was measured at different reaction times and at temperatures 0, 22, 40, and 60 °C. The plotted results of ln[nicotine] vs. time t at 0, 22, 40, and 60 °C in Fig. 2 demonstrate a good linear relationship in agreement with equation 2, and validates the assumption of the first order reaction kinetics. Figure 3 shows the slope of the plot of lnk vs. the reciprocal of T and the intercept (lnA). When applying equation 3, A is obtained as 2.46 × 105 min−1 and the activation energy (Ea) for nicotine protonation is 30.05 kJ mol−1.

Figure 2.

Dependence of ln[nicotine] on reaction temperature T (°C).

Figure 3.

The relationship between ln k and 1/T for protonation of nicotine in HCl solution.

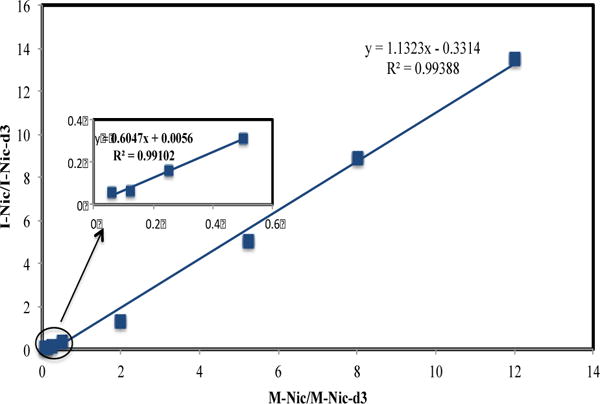

Calibration curve of protonated nicotine by FT-ICR-MS

Having confirmed complete protonation of nicotine, we proceeded to measure nicotine in e-liquids and aerosols of electronic cigarettes by FT-ICR-MS. A nicotine calibration curve using FT-ICR-MS for quantitative measurement was obtained by plotting the ratio of the relative abundance of nicotine to an internal standard (y) against the mole ratio of the analyte to the internal standard (x). Deuterated nicotine (nicotine-d3) was used as the internal standard, and this gave reproducible measurements. In addition, the deuterated nicotinium ion, [nicotine-d3-H]+, gave a strong and stable signal ion in FT-ICR-MS at m/z =164.1418. In this study, a fixed amount of 7.78 nano-mole of protonated deuterated nicotine was added to serially diluted protonated nicotine solutions as an internal reference to obtain a calibration curve. Figure S3 in Supplementary Information shows the FT-ICR-MS spectra overlay of the calibration working samples at different protonated nicotine concentrations. Figure 4 shows the calibration curve of nicotine measured by FT-ICR-MS that was used to determine the amount of nicotine in all e-liquids as well as the collected aerosols for puff-by-puff nicotine delivery measurements. The calibration curve showed an excellent linearity between the intensity ratio of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 (I-Nic/I-Nic-d3) and the molar ratio of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 (M-Nic/M-Nic-d3) in the working mole ratio range of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 from 1 to 12 (y= 1.1323x−0.3315, R2 =0.99388). To determine the limit of detection (LOD) for nicotine, a series of low concentration nicotine samples was prepared and analyzed by FT-ICR-MS. The insert in Figure 4 shows the linearity between the intensity ratio of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 and the molar ratio of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3. The LOD of nicotine defined as nicotine signal-to-noise ratio of 3 (S/N=3) was obtained as 1×10−12 mol/L.

Figure 4.

The calibration curve of nicotine by plotting the ratio of intensity of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 (I-Nic/I-Nic-d3) against the ratio of the amounts (mole) of nicotine–to–nicotine-d3 (M-Nic/M-Nic-d3).

Nicotine levels in e-liquids

To validate the method of protonation of nicotine in e-liquids and analysis by FT-ICR-MS, a known amount of nicotine was spiked into a PG/VG (50/50) mixture (zero nicotine e-liquid). One aliquot of the mixture was used for protonation of nicotine described in e-liquids and analyzed by FT-ICR-MS, and the other aliquot was used for extraction of nicotine to ethyl acetate from the e-liquid humectants and analyzed by GC-MS. The results indicated that the FT-ICR-MS analysis was within 2% difference from the spiked amount of nicotine, while the GC-MS analysis was 10 to 15% less than the spiked amount of nicotine due to the loss of nicotine from ethyl acetate extraction. After validation of the method of protonation of nicotine in e-liquids, Popular brands of e-liquids and blu plus® cartridges shown in Table 1 were examined for nicotine content. The measured nicotine values for all e-liquid brands in Table 1 had standard deviations less than 7%. Of the 10 brands tested, we found that the range difference between the measured nicotine content and the manufacturer-specified content ranged from −2.9% to 25.2%.

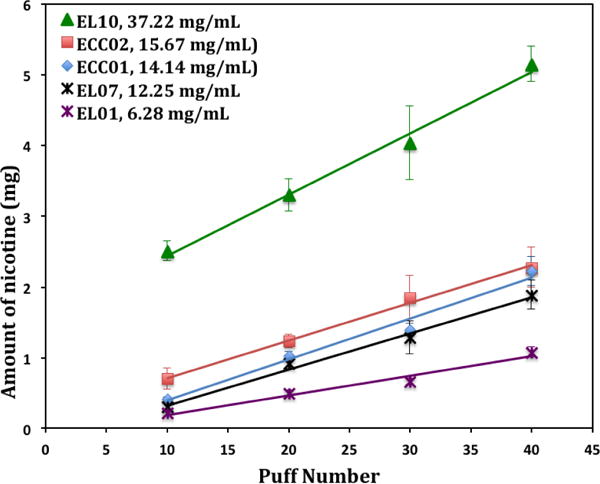

Nicotine levels in e-cigarette aerosols

The smoking robot was used to generate aerosols from blu plus® e-cigarette filled with a number of e-liquids. The generated aerosol flowed through three traps (impingers) connected in a series. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the data were expressed as the average [±SD] of the measured values. Figure 5 shows the plots of nicotine in aerosol vs. the puff number for five different e-liquids with measured actual nicotine level from 6.28 mg/mL to 37.22 mg/L shown in Table 1. There is a good linear relationship between the total amount of nicotine in the aerosols and the puff number in the studied puff number range. The measurements indicate the difference of nicotine in aerosols even for 10 puffs from e-cigarette cartridge ECC01 (measured nicotine 14.14 mg/mL) and ECC02 (measured nicotine 15.67 mg/mL) even though both cartridges were labeled as 13–16 mg/mL of nicotine level. The slopes relate to the efficacy of nicotine delivery of the e-cigarette related to the tested e-liquids. Table 2 shows a comparison of nicotine in aerosols of e-cigarettes collected by the impinger method and the NIOSH 2551 sorbent method. The results indicate that nicotine collected by the sorbent tube method has consistently lower values than that collected by the impinger method. The lower values of the NIOSH method were induced by the escape of nicotine from the sorbent tube and incomplete desorption of nicotine from the sorbent.

Figure 5.

Nicotine delivery profile for e-cigarette cartridges and e-liquids with different nicotine levels.

Table 2.

Comparison of measurements of nicotine in aerosol samples collected by sorbent tube and impinger methods.

| E-liquids | EL01 (mg) |

ECC01 (mg) |

EL10 (mg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 puffs | Sorbent | 0.104 | 0.184 | 2.07 |

| Impinger | 0.214 | 0.422 | 2.51 | |

| 20 puffs | Sorbent | 0.214 | 0.406 | 2.86 |

| Impinger | 0.488 | 1.03 | 3.29 | |

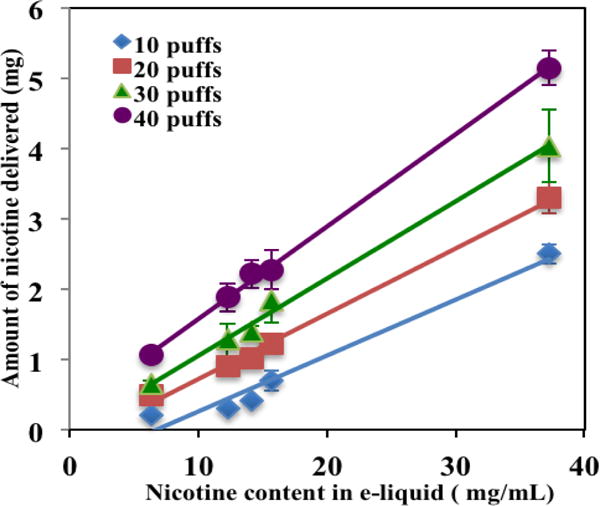

Figure 6 shows plots of measured nicotine concentration in the e-liquids vs the amount of nicotine in aerosols at constant puff numbers of 20, 30, 40. Again, there is a good linear relationship between nicotine concentration in these e-liquids vs nicotine amount in aerosols at the same total puff numbers. These results show that the amount of nicotine in aerosols depends on both its level in e-liquids and puff numbers.

Figure 6.

The relationship between nicotine in aerosol and nicotine levels in the e-liquids at constant puff number.

The average nicotine levels in aerosols for a single puff at the puff volume of 91 ml/puff were from 21 μg of e-liquid EL01 with 6.28 mg/mL nicotine to 42 μg of e-liquid ECC01 cartridge with 14.14 mg/mL nicotine. Previous publications indicates nicotine levels from a single puff of 70 mL e-liquids was between 1.7 and 51.3 μg.17 However, the nicotine levels in e-liquids, puff volume and e-cigarette power affect nicotine level in aerosols. Therefore, it is hard to make an accurate comparison. A dose inhaled from one conventional cigarette smoke was measured from 1.54 to 2.0 mg.22 If assuming a series of 10 puffs of e-cigarettes is equivalent to smoking one tobacco cigarette, the e-liquids might deliver 0.21 mg to 0.42 mg nicotine, which is lower than one tobacco cigarette. Our results appear to confirm previously reported finding.23 However, if the e-liquid with the highest nicotine level of 37.22 mg/mL in this study is used, the e-cigarette may deliver 2.5 mg for 10 puffs of aerosols which is comparable with nicotine inhaled from the mainstream smoke of one tobacco cigarette. A survey of e-liquid market indicates that some e-liquid manufactures provide the highest nicotine strength of 36 to 42 mg/mL in e-liquids.

Conclusions

We have developed a new method for collection and analysis of nicotine in the aerosols of e-cigarettes. The method involves protonation of nicotine to exploit use of FT-ICR-MS for nicotine quantification. The kinetics of nicotine protonation was determined as a first order reaction. The activation energy (Ea) for nicotine protonation was found to be 30.05 kJ mol−1. The measured nicotine levels of commercial e-liquids were within a difference range of −2.94% to 25.20% from the manufacturer specified values. Nicotine in aerosols linearly increased as the number of puffs increased. Nicotine in aerosols also linearly increases with the nicotine concentration in e-liquids at the same puff number.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant numbers P50HL120163, from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), HL122676, and GM 103492 from NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. MAO thanks the UofL School of Interdisciplinary and Graduate Studies for a graduate research fellowship. We acknowledge Dr. Pawel Lorkiewicz for help with FT-ICR-MS measurements.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(4):472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchiyama S, Ohta K, Inaba Y, Kunugita N. Anal Sci. 2013;29(12):1219–1222. doi: 10.2116/analsci.29.1219. doi: http://doi.org/10.2116/analsci.29.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vansickel AR, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1493–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoshiba K, Nagai A, Yasui S, Konno K. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;127(2):186–194. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(96)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015;64(14):381–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. NCHS data brief. Vol. 217. Center for Disease Control and Prevention Web site; 2015. pp. 1–8. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db217.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribisl KM, Seidenberg AB, Orlan EN. J Pol Anal Manag. 2016;35(4):978–983. doi: 10.1002/pam.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etter JF, Zäther E, Svensson S. Analysis of refill liquids for electronic cigarettes. Addiction. 2013;108(9):1671–1679. doi: 10.1111/add.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yildiz D. Nicotine, its metabolism and an overview of its biological effects. Toxicon. 2004;43(6):619–632. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickworth WB, Fant RV. Endocrine effects of nicotine administration, tobacco and other drug withdrawal in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benowitz NL, Porchet H, Sheiner L, Jacob P. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44(1):23–28. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuller HM. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38(20):3439–3442. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambers DS, Clark KE. The maternal and fetal physiologic effects of nicotine. Semin Perinatol. 1996;20(2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(96)80079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer B. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(1):5–7. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sleiman M, Logue JM, Montesinos VN, Russell ML, Litter MI, Gundel LA, Destaillats H. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(17):9644–51. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tayyarah R, Long GA. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;70:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goniewicz ML, Kuma T, Gawron M, Knysak J, Kosmider L. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:158–166. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trehy M, Ye W, Hadwiger ME. J Liq Chrom Rel Tech. 2011;34:1442–1458. doi: 10.1080/10826076.2011.572213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson RJ, Hensel EC, Morabito PN, Roundtree KA. PLOS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/jounal.pone.0129296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans SE, Hoffman AC. Tob Control. 2014;23:ii23–29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Hellani A, El-Hage R, Baalbaki R. Free-Base and Protonated Nicotine in Electronic Cigarette Liquids and Aerosols. Chem Res Toxicol. 2015;28(8):1532–1537. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Djordievic M, Stellman SD, Zang E. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:106–111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.