Abstract

The model Aquilegia coerulea x “Origami” possesses several interesting floral features, including petaloid sepals that are morphologically distinct from the true petals and a broad domain containing many whorls of stamens. We undertook the current study in an effort to understand the former trait, but additionally uncovered data that inform on the latter. The Aquilegia B gene homolog AqPI is shown to contribute to the production of anthocyanin in the first whorl sepals, although it has no major role in their morphology. Surprisingly, knockdown of AqPI in Aquilegia coerulea x “Origami” also reveals a role for the B class genes in maintaining the expression of the C gene homolog AqAG1 in the outer whorls of stamens. These findings suggest that the transference of pollinator function to the first whorl sepals included a non-homeotic recruitment of the B class genes to promote aspects of petaloidy. They also confirm results in several other Ranunculales that have revealed an unexpected regulatory connection between the B and C class genes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13227-017-0085-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aquilegia, Homeosis, Floral development, MADS box genes, ABC model, Petaloidy

Findings

Background

Botanists make very clear distinctions between petals and petaloidy. Petals, being synonymous with the corolla, are defined by the Plant Ontology Consortium as the inner whorl of non-reproductive organs that surround the androecium [1]. While these organs are often showy, the primary traits that define them are their position in the flower (the second whorl) and the fact that they are sterile. In contrast, “petaloidy” refers to an organ’s appearance and indicates non-photosynthetic organs that are modified for pollinator attraction. Petaloid organs can occur in any whorl of the flower or even be extra-floral (e.g., bracts in Poinsettia). Both second whorl petals and the general appearance of petaloidy have evolved many different times independently across the angiosperms [2]. The discovery of the genetic program controlling floral organ identity, the so-called ABC model [3], gave us candidate genes—homologs of the B class petal identity genes APETALA3 (AP3) and PISTILLATA (PI)—to explore the molecular basis of petaloidy in all its possible iterations.

The homeotic nature of the ABC model suggests a simple model in which petaloid organs can arise by spatial shifts of the B gene expression domain [4, 5]. This appears to be the case in many monocots with undifferentiated petaloid perianths, such as tulips or lilies, in which B gene expression is commonly observed in all of the perianth organs (reviewed [6]). Such undifferentiated perianths are less common in dicots, but a similar pattern has been described for lobelioid Clermontia [7]. In these examples, the first and second whorl organs are very similar at maturity, suggesting that a single organ identity program is being broadly expressed. In many other instances, however, the sepals may be petaloid, but they differ considerably in morphology relative to the petals. Several such examples have now been studied, and most of these petaloid sepals lack B gene expression, suggesting that the development of petaloid features in these organs is due to convergence rather than any degree of homeosis (e.g., [8–10]).

So are there any instances where B genes contribute to the petaloidy of the sepals? There is one clear example, in orchids, in which B class genes appear to be critical to the establishment of separate petaloid identity programs in both the sepals and petals via the deployment of AP3 paralogs [11, 12]. In Aquilegia, previous work has shown that the B class genes do not contribute to the identity of the sepals, either in terms of their gross morphology or their cell types [13]. However, these functional tests were always done using the ANTHOCYANIDIN SYNTHASE (AqANS) gene as a marker (e.g., Fig. 1b), so it cannot be ruled out that the B gene homologs contribute to anthocyanin production. We, therefore, decided to repeat this experiment using a virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) construct that only contained AqPI in order to determine whether color production in the sepals was affected. We have found that expression levels of multiple members of the anthocyanin pathway are reduced in these flowers, but, in addition, we recovered a novel phenotype, suggesting that the B class genes are required for the maintenance of AGAMOUS (AG) homolog expression in the outer whorls of stamens.

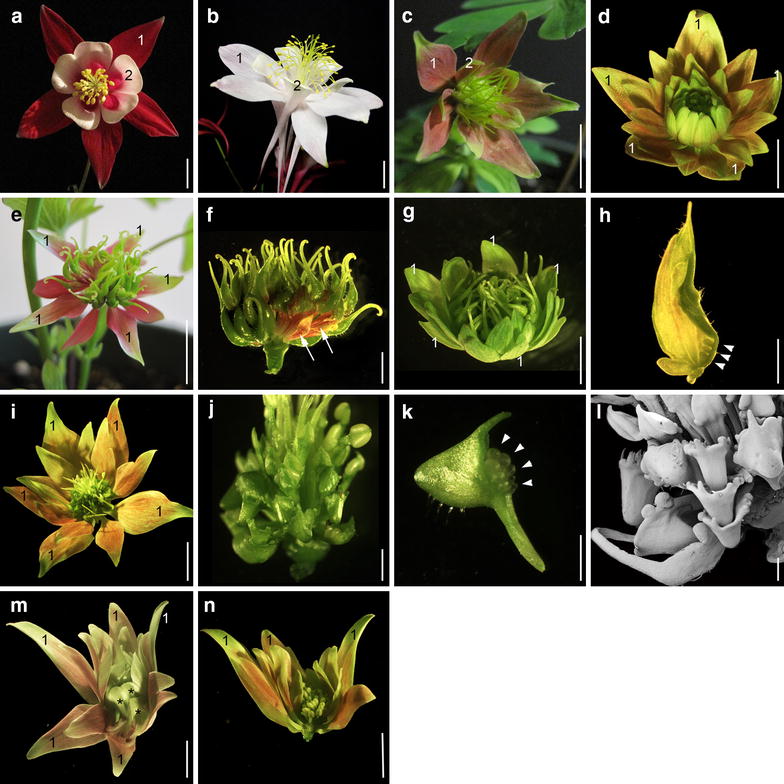

Fig. 1.

Phenotypes recovered in Aquilegia x coerulea AqPI-VIGS flowers. a Wild-type flower with labeled first whorl sepals (1) and second whorl petals (2). b Flower with only AqANS-silencing, sepals and petals labeled as in a. c–g, i, m, n Range of floral phenotypes recovered from AqPI-VIGS plants. Wherever possible, we have indicated the first whorl sepals with the label “1.” All other sepals are transformed petals or stamens. In most of these flowers, all sepals, regardless of their position, show varying degrees of color loss, ranging from pale pink (e.g., c, d) to pale green (e.g., g). While half of the recovered flowers exhibited the standard B class mutant phenotype with petal to sepal and stamen to carpel transformation (e.g., c), we commonly observed transformations in which the outer whorls of reproductive organs became sterilized, most often into sepals, rather than the expected stamen to carpel transformation (e.g., d, g, i, m, n). Weak or variable silencing produced complex organs, including sepal/carpels, as seen in the flower in e, which is shown with its perianth removed in f. Arrows indicate sepaloid base of chimeric carpels. h A single sepal/carpel chimeric organ from the flower in g, with ectopic ovules indicated by arrowheads. Also observed in inner whorls were petal/carpels, as shown in i–l, and sepal/petals, as in m (asterisks indicate inner petaloid organs). The reproductive whorls of the flower in i are shown under light microscopy in j and scanning electron microscopy in l. A single petal/carpel chimera is shown in k, with arrowheads indicating ectopic ovules. In flowers showing the weakest silencing, the petals and outermost stamens were transformed into sepals, but internal stamen whorls retained their identity (n). Size bars 10 mm in a–e, g, i, m, n; = 2.5 mm in f, h, j; = 1 mm in k and l

Results

AqPI-VIGS plants exhibit a range of floral phenotypes

After treating 90 plants with TRV2-AqPI, we recovered 50 flowers with homeotic phenotypes, which fell into two broad classes. In the first class, there were 25 flowers that displayed canonical B gene mutant phenotypes with petal to sepal and stamen to carpel transformations (Fig. 1c). Aquilegia has a fifth class of floral organs, the sterile staminodia, which are similarly transformed into carpels in these flowers. These flowers had no more than ten sepals in total, representing the first whorl sepals and the transformed second whorl organs (Table 1). Surprisingly, we also recovered 25 flowers that presented novel phenotypes due to sterilization of the outer reproductive whorls. In these flowers, there were commonly extra whorls of sepals that appear to be in place of the outer whorls of fertile organs (Fig. 2d, g, i, m; Table 1). Consistent with the variable nature of VIGS, this transformation was incomplete in some cases, yielding sepal/carpel (Fig. 1e–h), petal/carpel (Fig. 1j–l) or sepal/petal (Fig. 1m) chimeras. In all of these flowers, the sepals show various degrees of color loss, regardless of their position in the flower (Fig. 1c–e, g, i, m). These sepals are not white as in AqANS-VIGS flowers, but rather pale green (compare Fig. 1b–d, g, or i).

Table 1.

Organ counts in control and silenced flowers

| Sepals | Petals | Stamens | Staminodia | Carpels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRV2-AqANS | 5 ± 0 | 5 ± 0 | 43.1 ± 5.8 | 10 ± 0.97 | 5 ± 0.51 |

| TRV2-AqPI | |||||

| Class I | 9.5 ± 0.48 | 0 | 9.2 ± 4.27 | 0 | 55.2 ± 7.95 |

| Class II | 21.2 ± 8.79 | 1 ± 1.8 | 10.25 ± 18.5 | 1 ± 4.4 | 33.5 ± 17.06 |

Fig. 2.

qRT-PCR analyses of gene expression levels in AqPI-VIGS tissue. a Expression of AqPI in first whorl organs (W1), second whorl organs (W2), stamens transformed into sepals (STA to SEP), stamens transformed into petals (STA to PET), and stamens transformed into carpels (STA to CAR). All values are normalized to the expression of AqPI in control AqANS-VIGS samples for each organ type (dotted line). b Expression of the three Aquilegia AP3 homologs in same samples as a. All values are normalized to the expression levels of each gene in control samples for each organ type (dotted line). c Expression of AqAG1 in stamens transformed to sepals (STA to SEP), stamens to petals (STA to PET), and stamens to carpels (STA to CAR). All values are normalized to the expression of AqAG1 in control AqANS-VIGS stamens (dotted line). d Expression of AqPI, AqANS, AqF3H, and AqDFR across two classes of sepal tissue: AqANS-VIGS control tissue and AqPI-VIGS tissue. All values are normalized relative to the expression of each gene in untreated sepals (dotted line). All vertical axes represent relative expression levels, all asterisks indicate expression levels that are significantly different from the reference control organs, and all error bars represent standard deviation

Down-regulation of AqPI results in contraction of the AqAG1 expression domain and the anthocyanin production pathway

We used qRT-PCR to quantify silencing of AqPI in all affected floral organs (Fig. 2a). Every tissue tested showed 80–95% silencing except the stamen/petal chimeras, which is not surprising given their retained petal identity. We also examined the expression of the three main AP3 homologs (Fig. 2b). In the first whorl sepals, we only examined AqAP3-1 and AqAP3-2 because AqAP3-3 is expressed at extremely low levels in these organs [13]. AqAP3-1 expression was slightly lower in the sepals and transformed stamens, but increased in the transformed second whorl petals. We have previously observed increased AqAP3-1 expression in AqPI-VIGS tissue [13], so this is not particularly surprising. AqAP3-2 and AqAP3-3 expression was generally decreased in all the organs, except for an increase of AqAP3-3 in the stamen to petal transformed organs, which is consistent with the petal-specific expression of this paralog [13].

In Aquilegia, there are two homologs of the C class gene AGAMOUS, AqAG1 and AqAG2. In the mature organs used to assess expression in VIGS experiments, AqAG1 is expressed in both stamens and carpels, but AqAG2 is only detectable in carpels [13], making it unsuitable for analysis of stamen transformations. Examination of AqAG1 revealed that its expression was, in fact, dramatically reduced in the sterilized organs (Fig. 2c); however, when stamens were transformed into carpels, AqAG1 expression remained strong.

Finally, we tested the expression of three members of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway: ANTHOCYANIDIN SYNTHASE (AqANS), FLAVONOID 3-HYDROXYLASE (AqF3H), and DIHYDROFLAVONOL 4-REDUCTASE (AqDFR) (Fig. 2d). Note that AqF3H and AqDFR would be expected to be upstream in the anthocyanin synthesis pathway relative to AqANS [14]. When AqANS is silenced alone, only this member of the synthesis pathway decreases; however, when AqPI is silenced alone, all three synthesis genes show decreased expression compared to untreated sepals, although the decrease in AqF3H expression was too variable to be significant.

Conclusions

The primary goal of this experiment was to test whether the B class genes in Aquilegia contribute to color production in the petaloid sepals, which required conducting AqPI silencing without the presence of the marker AqANS. Our results reveal that the B gene homologs do, in fact, promote activation of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway in sepals, but we also recovered unexpected evidence for a role of the B class genes in maintaining the outer extent of the C class domain.

Homologous transference of function without homeosis in Aquilegia sepals

It is very common across the order Ranunculales to observe petaloid sepals, an example of what is termed transference of function, which Baum and Donoghue [15] defined as when “an ecological function performed by one structure comes to be carried out by a new structure.” In this case, the ecological function is pollinator attraction, a role that is often shared between the sepals and petals of these taxa. Unlike the undifferentiated petaloid perianths of the monocots, however, the Ranunculales have morphologically distinct sepals and petals (reviewed [16]). In fact, ranunculid petals, which typically bear nectaries, are often significantly reduced and even entirely lost in some genera. We have hypothesized that this reduction or loss of petals is facilitated by the fact that the sepals have acquired pollinator attractive functions, thereby releasing constraints on the morphology and even the presence of the petals [16].

But how did this transference of function occur? What is the genetic basis of petaloidy in the sepals? Baum and Donoghue posit two general mechanisms for transference of function, one relying on a spatial shift in the expression of a preexisting developmental program, which often results in homeosis, and the other involving convergent evolution of the functional traits without homeosis [15]. As discussed above, several examples of the latter have been observed in which petaloidy has evolved without the apparent involvement of the B class genes. Our initial studies suggested that this was also the case in Aquilegia: Although expression of B gene homologs can be detected in late-stage sepals [17], no expression was observed during the stages associated with establishment of organ identity and knockdown of the critical B gene AqPI had no effect on sepal morphology or cell types [13].

The current study has demonstrated that the reality of the situation is more complicated. Although the observed late B gene expression does not appear to be required for organ identity, it is important to the production of color in these organs. This indicates that there is what we would term partial process homology between the sepals and petals—the organs share some aspects of their developmental programs. Within Baum and Donoghue’s scheme, this condition would be considered homologous transference of function (utilization of a preexisting genetic program) without homeosis. This is distinct from other recently described cases of petaloidy in first whorl organs. In the liliaceous monocot Tricyrtis, the B gene homologs promote identity of both perianth whorls [18], while in orchids, it appears that duplications in the AP3 homologs allow the flowers to differentially encode three distinct petaloid organ identities [11, 12].

The loci that control the fundamental identity of Aquilegia sepals, including the production of petaloid-associated papillated cells on the epidermis, remain unknown, but in another ranunculid model, Nigella damascena, an AGL6 homolog has been shown to promote sepal identity [19]. Although the B genes may not be influencing identity per se, it is also interesting to ask if they are solely promoting anthocyanin or perhaps playing additional roles. Studies in A. thaliana have found that the B genes directly target loci involved in photosynthesis in order to repress these genes and allow the white color of the petal [20]. We tested whether homologs of these genes, called BANQUO1/BANQUO2, were up-regulated in our AqPI-VIGS sepals, but we did not recover any consistent results (data not shown). It remains possible that the Aquilegia B genes are important for both activation of the anthocyanin pathway and down-regulation of photosynthesis in the sepals.

Requirement of B gene function for maintenance of C gene expression

In the canonical ABC model, A and C class genes cross-regulate each other, but the B class genes are not essential for the expression of the other two classes [21]. ChIP-seq studies have shown that AP3-containing MADS complexes do target AG, which is also known to feedback positively onto its own expression (reviewed [22]). In A. thaliana, this positive feedback can be mediated by any MADS complex containing AG and does not strictly require AP3/PI [23]. In two deeply divergent members of the Ranunculales, it appears that the outer extent of the C expression domain requires B gene expression [24]. In Eschscholzia californica of the Papaveraceae, the seirena mutant, a loss of function allele of a PI/GLO homolog, shows the typical transformation of petals into sepals and most stamens into carpels, but the outer stamens are instead transformed into sepals [25]. The authors clearly demonstrate that this is due to homeosis associated with reduced expression of the C class EscAG1 locus. In N. damascena, the situation is somewhat more complicated. Here, an insertional loss of function allele of the AP3 homolog NgsAP3-3 appears to show transformation of petals into sepals and outer stamens into sepals [26, 27]. This is unexpected because AP3-3 orthologs in the Ranunculaceae are commonly petal specific [16], which makes it surprising that the locus would have an impact on AG expression in the stamens. However, in N. damascena, the early expression of NgsAP3-3 is broader than just the second whorl, clearly encompassing a region that would cover the outer whorls of stamens [26, 27]. Moreover, the other AP3 paralogs in N. damascena are weakly expressed at very early stages, so NgsAP3-3 is likely to be the predominant AP3 copy during stamen initiation. Further analysis of the NgsAP3-3 down-regulation phenotype clearly demonstrated that it involves stamen to sepal transformation in conjunction with a contraction in the NgsAG1 expression domain [19].

Our A. coerulea results are, nonetheless, rather surprising because we had not previously observed this phenotype in our TRV2-AqPI-AqANS study in the Old World species A. vulgaris [13]. Perhaps, this was an experimental artifact reflecting the fact that although we recovered many silenced flowers in the original study, they were derived from a small number of plants. Despite the fact that both experiments used VIGS, it may be that the silencing obtained in the current study is stronger or was established earlier in development. Alternatively, there may be differences between species of Aquilegia in terms of the degree to which B genes are absolutely necessary for this function. Previous studies of Old World and New World species of Aquilegia have uncovered significant differences in the genetics underlying aspects of their floral development [28, 29]. Likewise, in the Papaveraceae, the phenotype was observed in Eschscholzia, but not when B class homologs were silenced in Papaver [30]. In any case, we now appear to have independent sets of data from three divergent ranunculid taxa, demonstrating that B gene homologs are important for the initiation and/or maintenance of the outer extent of the AG homolog expression domain.

There are a number of possible contributors to the dependence of C gene expression on B gene function. First, as already noted, Arabidopsis thaliana MADS complexes containing AP3/PI do participate in positive feedback onto AG, so it may be that the process of developmental system drift [31] has produced a different pattern of regulatory redundancies that increased the importance of the B genes in this process. It is also interesting to note that in all three of these taxa—Eschscholzia, Nigella, and Aquilegia—the stamens are not present as a single whorl, but rather a broad domain encompassing many organs. In A. thaliana, AG expression is promoted by the activity of LEAFY (LFY) in conjunction with several other factors, including WUSCHEL (WUS), which is tightly expressed in the center of the meristem, but whose protein diffuses non-cell autonomously outward [32]. We currently know nothing about how AG homolog expression is activated in Ranunculales or in any angiosperm with a broad domain of stamens. Is activation still dependent primarily on WUS? Does WUS diffuse all the way to the outermost extent of the stamen domain? Perhaps not. It may be that spatial limitations in the extent of WUS diffusion have led to the evolution of a greater dependence on the B class genes for activation of AG in the outer regions of the stamen domain. Further genetic dissection of ABC gene regulation in multiple ranunculid models will provide insight into the developmental basis of this common floral morphology.

Methods

Virus-induced gene silencing

The Aquilegia VIGS protocol and construction of the TRV2-AqANS positive control plasmid have been previously described [13, 33]. To make the TRV2-AqPI construct, we PCR-amplified a 326-bp fragment of AqPI using primers that added XbaI and BamHi sites to the respective 5′ and 3′ ends of the PCR product (5′ GGTCTAGAGCTTGGCGGGAATGATAGAGAAATGGAAAATG, 5′ AAGGATCCCCATAATCAAGAGAAACTTTAAAATCATGGATA). This PCR product was used to produce the TRV2-AqPI construct in a manner similar to Gould and Kramer [33]. A total of 90 A. coerulea “Origami” plants at the four to six true leaf stage were vernalized at 4°C for three weeks, and then, one day after the plants had been removed from vernalization, they were treated as described for seedlings in [33]. Totally, 90 control plants were also treated with TRV2-AqANS. Flowers showing any floral phenotypes were photo-documented and, upon maturation, the flowers were dissected. All individual perianth organs were photographed using a Kontron Elektronik ProgRes 3012 digital camera mounted on a Leica WILD M10 dissecting microscope (Harvard Imaging Center). For the purposes of counting organ types, organs were scored as sepals if they lacked spurs and had lanceolate apices; organs were scored as petals if they had rounded apices and some degree of spur development; organs were scored as stamens if they had filaments and some degree of anther development; organs were scored as staminodia if they were sterile; and organs were scored as carpels if they possessed ovules. For every flower showing silencing, a selection of organs from each whorl was either flash frozen at − 80° for subsequent RNA analysis or fixed in freshly prepared, ice-cold FAA for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. This process was also repeated for several untreated flowers as well as flowers that were treated with TRV2-AqANS as controls. SEM analysis and light microscopy were performed as described in [13].

Expression analysis of VIGS-treated organs

Total RNAs were prepared from collected floral organs using the Qiagen RNeasy kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Each RNA sample was treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion by Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Individual cDNAs were synthesized using 1 µg of total RNA (SuperScript III™ First Strand Synthesis, Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). All primer sequences are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The primers were tested for amplification efficiency using a cDNA dilution series as templates. The efficiency (E) of the primers was determined using the slope of the linear regression line in Microsoft Excel 2015 (E = 10[(−1/slope)−1] × 100). The specificity of each primer pair was verified by dissociation curve analysis (60–95 °C). The quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using PerfeCTa qPCR FastMix, Low ROX (Quanta Biosciences Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in the Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Relative expression levels were calculated based on the 2 − ΔΔCt method [34]. AqIPP2 (GenBank KC854337) was used as the reference gene for expression normalization.

Several different sample types were examined. We determined AqPI expression in five different classes of tissue selected to represent a range of phenotypes: first whorl organs (sepals showing color changes), second whorl organs (petal to sepal transformations), and three classes of stamen transformations (stamen to sepal, stamen to petal, and stamen to carpel). Each class contained three to six separate samples, and each sample was analyzed in three technical replicates. These values were averaged across all of the silenced organs in that class and compared to equivalent pooled RNA samples from organs dissected from AqANS-VIGS flowers (Fig. 2a). The silenced sepals, petal to sepal transformants, stamen to sepal transformants, and stamen to petal transformants were similarly tested for the expression of all three main AqAP3 paralogs (Fig. 2b). These experimental values were normalized to AqAP3-1, AqAP3-2, and AqAP3-3 expression levels in control AqANS-VIGS samples. We examined AqAG1 expression in a variety of transformed stamen classes and normalized those values to AqAG1 expression in AqANS-VIGS stamens (Fig. 2c). Lastly, we determined the expression of three members of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway (AqANS, AqF3H, and AqDFR) in sepals from AqANS-VIGS flowers and AqPI-VIGS flowers, with the values normalized to the corresponding gene expression levels of those genes in wild-type sepals. All results presented are the mean ± standard deviation of the examined samples, normalized to the appropriate reference sample as described above. All error bars represent standard deviation, and unpaired Student’s t-tests were used to determine the statistical significance of differences between experimental and control values.

Authors’ contributions

BS and EMK coordinated and conceived of the study; EMK prepared the TRV2-AqPI construct; BS conducted all other experiments; BS and EMK interpreted the data, and drafted, revised, and approved the final article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of the Kramer Lab and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. IOS-07200240 to E.M.K).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AP3

APETALA3

- PI

PISTILLATA

- ANS

ANTHOCYANIDIN SYNTHASE

- AG

AGAMOUS

- VIGS

virus-induced gene silencing

- F3H

FLAVONOID 3-HYDROXYLASE

- DFR

DIHYDROFLAVONOL 4-REDUCTASE

- E. californica

Eschscholzia californica

- N. damascena

Nigella damascena

- LFY

LEAFY

- WUS

WUSCHEL

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13227-017-0085-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Bharti Sharma, Email: bsharma@cpp.edu.

Elena M. Kramer, Email: ekramer@oeb.harvard.edu

References

- 1.Cooper L, Walls RL, Elser J, Gandolfo MA, Stevenson DW, Smith B, Preece J, Athreya B, Mungall CJ, Rensing S, et al. The plant ontology as a tool for comparative plant anatomy and genomic analyses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1–23. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanis M, Soltis PS, Qiu Y-L, Zimmer EA, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analyses and perianth evolution in basal angiosperms. Ann Miss Bot Gard. 2003;90:129–150. doi: 10.2307/3298579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM. The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature. 1991;353:31–37. doi: 10.1038/353031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman JL. Evolutionary conservation of angiosperm flower development at the molecular and genetic levels. J Biosci. 1997;22:515–527. doi: 10.1007/BF02703197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer EM, Irish VF. Evolution of the petal and stamen developmental programs: Evidence from comparative studies of the lower eudicots and basal angiosperms. Int J Plant Sci. 2000;161:S29–S40. doi: 10.1086/317576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanno A, Nakada M, Akita Y, Hirai M. Class B gene expression and the modified ABC model in nongrass monocots. Sci World J. 2007;7:268–279. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofer KA, Ruonala R, Albert VA. The double-corolla phenotype in the Hawaiian lobelioid genus Clermontia involves ectopic expression of PISTILLATA B-function MADS box gene homologs. EvoDevo. 2012;3:26. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geuten K, Becker A, Kaufmann K, Caris P, Janssens S, Viaene T, Theissen G, Smets E. Petaloidy and petal identity MADS-box genes in the balsaminoid genera Impatiens and Marcgravia. Plant J. 2006;47:501–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brockington SF, Rudall PJ, Frohlich MW, Oppenheimer DG, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. ‘Living stones’ reveal alternative petal identity programs within the core eudicots. Plant J. 2012;69:193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis JB, Barnett LL, Hileman LC. Evolution of petaloid sepals independent of shifts in B-class MADS box gene expression. Dev Gen Evol. 2012;222:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mondragon-Palomino M, Theissen G. Why are orchid flowers so diverse? Reduction of evolutionary constraints by paralogues of class B floral homeotic genes. Ann Bot. 2009;104:583–594. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu HF, Hsu W-H, Yi Lee, Mao WT, Yang JY, Li JY, Yang CH. Model for perianth formation in orchids. Nat Plants. 2015;1:15046. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer EM, Holappa L, Gould B, Jaramillo MA, Setnikov D, Santiago P. Elaboration of B gene function to include the identity of novel floral organs in the lower eudicot Aquilegia (Ranunculaceae) Plant Cell. 2007;19:750–766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holton TA, Cornish EC. Genetics and biochemistry of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1071–1083. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum DA, Donoghue MJ. Transference of function, heterotopy and the evolution of plant development. In: Cronk QCB, Bateman RM, Hawkins JA, editors. Developmental genetics and plant evolution. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2002. pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen DE, Kramer EM, Zimmer EA. One size fits all? Molecular evidence for a commonly inherited petal identity program in the Ranunculales. Am J Bot. 2009;96:1–14. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer EM, Di Stilio VS, Schluter P. Complex patterns of gene duplication in the APETALA3 and PISTILLATA lineages of the Ranunculaceae. Int J Plant Sci. 2003;164:1–11. doi: 10.1086/344694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otani M, Sharifi A, Kubota S, Oizumi K, Uetake F, Hirai M, Hoshino Y, Kanno A, Nakano M. Suppression of B function strongly supports the modified ABCE model in Tricyrtis sp (Liliaceae) Sci Rep. 2016;6:24549. doi: 10.1038/srep24549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang PP, Liao H, Zhang WG, Yu XX, Zhang R, Shan HY, Duan XS, Yao X, Kong HZ. Flexibility in the structure of spiral flowers and its underlying mechanisms. Nat Plants. 2016;2:15188. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mara CD, Huang TB, Irish VF. The Arabidopsis floral homeotic proteins APETALA3 and PISTILLATA negatively regulate the BANQUO genes implicated in light signaling. Plant Cell. 2010;22:690–702. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.065946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development. 1991;112:1–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pajoro A, Biewers S, Dougali E, Valentim FL, Mendes MA, Porri A, Coupland G, Van de Peer Y, van Dijk ADJ, Colombo L, et al. The (r)evolution of gene regulatory networks controlling Arabidopsis plant reproduction: a two-decade history. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:4731–4745. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Mena C, de Folter S, Costa MMR, Angenent G, Sablowski R. Transcriptional program controlled by the floral homeotic gene AGAMOUS during early organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:429–438. doi: 10.1242/dev.01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker A. Tinkering with transcription factor networks for developmental robustness of Ranunculales flowers. Ann Bot. 2016;117:845–858. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange M, Orashakova S, Lange S, Melzer R, Theissen G, Smyth DR, Becker A. The seirena B class floral homeotic mutant of California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica) reveals a function of the enigmatic PI motif in the formation of specific multimeric MADS domain protein complexes. Plant Cell. 2013;25:438–453. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goncalves B, Nougue O, Jabbour F, Ridel C, Morin H, Laufs P, Manicacci D, Damerval C. An APETALA3 homolog controls both petal identity and floral meristem patterning in Nigella damascena L. (Ranunculaceae) Plant J. 2013;76:223–235. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang R, Guo C, Zhang W, Wang P, Li L, Duan X, Du Q, Zhao L, Shan H, Hodges SA, et al. Disruption of the petal identity gene APETALA3-3 is highly correlated with loss of petals within the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5074–5079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219690110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prazmo W. Genetic studies on the genus Aquilegia L. I. Crosses between Aquilegia vulgaris L. and Aquilegia ecalcarata Maxim. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 1960;29:57–77. doi: 10.5586/asbp.1960.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prazmo W. Genetic studies on the genus Aquilegia L. II. Crosses between Aquilegia ecalcarata Maxim. and Aquilegia chrysantha Gray. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 1961;30:423–442. doi: 10.5586/asbp.1961.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drea S, Hileman LC, de Martino G, Irish VF. Functional analyses of genetic pathways controlling petal specification in poppy. Development. 2007;134:4157–4166. doi: 10.1242/dev.013136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.True JR, Haag ES. Developmental system drift and flexibility in evolutionary trajectories. Evol Dev. 2001;3:109–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohmann JU, Hong RL, Hobe M, Busch MA, Parcy F, Simon R, Weigel D. A molecular link between stem cell regulation and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2001;105:793–803. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gould B, Kramer EM. Virus-induced gene silencing as a tool for functional analyses in the emerging model plant Aquilegia (columbine, Ranunculaceae) Plant Methods. 2007;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.