Abstract

This research, a descriptive qualitative analysis of self-defined serious illness goals, expands the knowledge of what goals are important beyond the physical—making existing disease-specific guidelines more holistic. Integration of goals of care discussions and documentation is standard for quality palliative care but not consistently executed into general and specialty practice. Over 14 months, lay health-care workers (care guides) provided monthly supportive visits for 160 patients with advanced heart failure, cancer, and dementia expected to die in 2 to 3 years. Care guides explored what was most important to patients and documented their self-defined goals on a medical record flow sheet. Using definitions of an expanded set of whole-person domains adapted from the National Consensus Project (NCP) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 999 goals and their associated plans were deductively coded and examined. Four themes were identified—medical, nonmedical, multiple, and global. Forty percent of goals were coded into the medical domain; 40% were coded to nonmedical domains—social (9%), ethical (7%), family (6%), financial/legal (5%), psychological (5%), housing (3%), legacy/bereavement (3%), spiritual (1%), and end-of-life care (1%). Sixteen percent of the goals were complex and reflected a mix of medical and nonmedical domains, “multiple” goals. The remaining goals (4%) were too global to attribute to an NCP domain. Self-defined serious illness goals express experiences beyond physical health and extend into all aspects of whole person. It is feasible to elicit and record serious illness goals. This approach to goals can support meaningful person-centered care, decision-making, and planning that accords with individual preferences of late life.

Keywords: goal-oriented, decision-making, palliative care, patient-centered care, patient preferences, serious illness

Introduction

People are living longer with multiple medical conditions,1 causing functional, social, and emotional stresses that threaten an individual’s independence and quality of life.2 Multiple comorbidities become serious illness in the presence of disease progression, complications with high mortality, disabling physical and cognitive decline, and significant disease burden that affects daily life, eventually leading to death.3,4 Disease management practices and guidelines rely on biomarkers5 and typically do not account for whole-person needs and individual preferences.6,7 Over the experience of a changing disease trajectory, personal preferences may proceed over a spectrum from desiring to cure, to living longer, to prioritizing meaning, and quality over quantity of life.8,9 This discordance between individual preferences and disease-specific guidelines makes it difficult to match care to desired preferences.

Person-centered, person-directed care10,11 can create challenges for providers in adhering to medical guidelines.12 Goal-oriented care better supports the health and well-being of chronic illness and end-of-life (EOL) care and recommends parting from problem-oriented medical care that focuses on diagnosing, treating, and fixing.13 Goal-oriented care14 promotes the use of self-defined health goals in decision-making and assists providers in managing multiple often conflicting, disease-specific guidelines and an individual’s ideal state of health.15 Palliative Care guidelines,16 preferred practices,17 and a recent Institute of Medicine report18 call for incorporation of earlier practices that include ongoing goals of care discussions and advance care planning (ACP). Research suggests substantial gaps remain between the type of care patients receive at the EOL and care they would prefer to receive,19,20 indicating a need to understand individual goals beyond physical, disease-specific medical care.

There is less understanding of care goals for patients with serious illness in the last years of life than for those who are sick enough to die within weeks or months.21 Most EOL goals focus on life-sustaining treatment options, whereas other goals are described in terms of varied and diverse outcomes of maintaining physical function and independence, relief from pain, symptoms, suffering, and longer survival.8,22 Current tools (eg, disease-specific guidelines and advance directives) designed to address medical needs and preferences are not well suited to individualized care of patient’s psychosocial nonmedical needs.23 Strategies to move palliative care upstream from traditional models of delivery suggest a shift to person-centered individualized care beyond the EOL experience.24 Whole-person planning could best be accomplished when self-identified physical and psychosocial goals have been elicited and shared.

Poor completion of advance directives and stated EOL concerns of Americans25 makes it difficult to know whether patients received desired care throughout the serious illness experience upstream from EOL preferences. To ensure care desired matches care received, we first need to expand our knowledge of what kind of goals are important beyond the physical domain and EOL planning—making goals of care discussions and disease-specific guidelines more holistic. This research is a descriptive analysis that examined whole-person goals of patients with serious illness identified during their last 2 to 3 years of life. The qualitative results should help to better understand whole-person priorities that could be missing from existing clinical assessments, disease-specific guidelines, decision-making, and care planning.

Methods

The current research is part of a 4-year late life supportive care study within a large Midwestern metropolitan health-care system in the United States. An upstream community-based palliative care approach, called LifeCourse, provided whole-person, patient-centered support alongside existing care services for patients and families with advanced medical conditions expected to be in the last 2 to 3 years of life. Intervention activities were expected to show positive results in quality of life, patient experience,26 and total cost of care. Trained lay health-care workers (care guides [CGs]) visited monthly and collaborated with the patients’ primary care team members. The CGs were supported by an interdisciplinary team that included nurses, social workers, a chaplain, a family therapist, and a pharmacist.27 Each CG supported patients through a set of palliative care activities, assessment tools,28–33 a whole-person conversation guide, and specific visits.34,35 This approach allowed the CG to provide a person-centered approach driven by self-defined goals, linking patients and families to existing health-care services and community resources. Subsequent to the research, CGs are being integrated into high-risk care management populations, primary and specialty care, and a federally qualified health center.

The present analysis was an initial inquiry to describe self-defined goals patients living with advanced heart failure, cancer, and dementia shared with their CG. The CGs entered goals into an electronic health record (EHR) flow sheet using direct quotes or patient-validated statements. A major focus of the CG work was to help patients’ articulate goals by identifying what was most important at the time. Each monthly visit utilized a framework that began with questions like, “What is most important to you?” and “What are you willing to work on?” The CGs used broad, uniform, open-ended questions to encourage identification of whole-person goals beyond illness and physical health. The CGs were trained in motivational interviewing to standardize the variability in individual approaches and encouraged exploration of patient-stated goals. This study was approved by the relevant institutional review boards. Patients consented to take part in the study, making their EHR data available for research purposes.

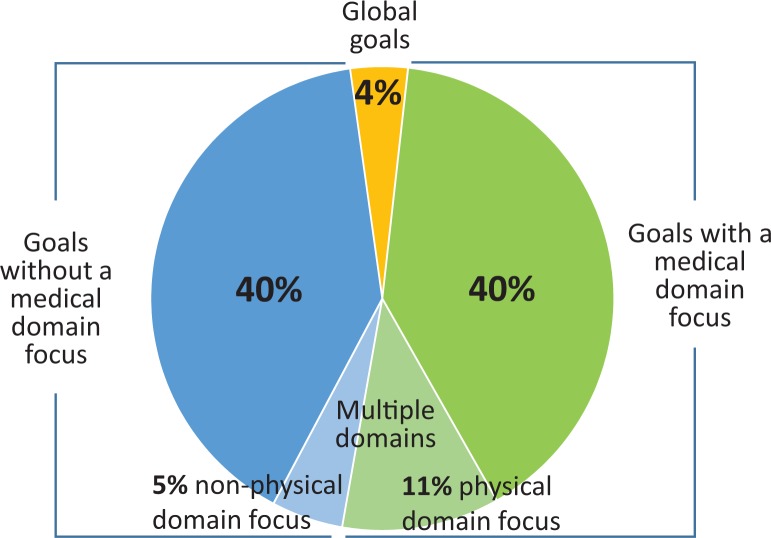

Researchers exhaustively sampled 160 patients, who enrolled during the first 17 months of the larger study period between November 7, 2012, and March 25, 2014 (Table 1). Researchers analyzed the contents of individual goals’ flow sheets, accommodating up to 30 goals that changed or were carried forward over time. Data were drawn from the “description” and “plan” flow sheet fields. Medical record documentation of goals available for the broader care team to review were automatically populated into the CG visit notes (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 160 Participants at Baseline.

| Characteristics | N = 160 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, mean (±SD) | 79 (11) |

| Female, n (%) | 77 (48) |

| Race: white, n (%) | 141 (88) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 57 (35) |

| College or 4-year degree | 73 (35) |

| Graduate school | 32 (20) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single, unmarried partners | 16 (16) |

| Married, domestic partners | 74 (46) |

| Divorced, separated | 27 (17) |

| Widowed | 43 (27) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Home | 106 (66) |

| Assisted living | 21 (13) |

| Nursing home | 33 (21) |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Cancer | 25 (16) |

| Dementia | 27 (17) |

| Heart failure | 108 (68) |

| Comorbidity score (SD) | 5 ± 1.5 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Example of serious illness goals documentation in the medical record.

Note. The patient Joanne is a fictionalized name.

The overarching analytic strategy for this research was a fundamental qualitative descriptive approach aimed to describe the content of patient goals in everyday language.36 Deductive analysis and coding were conducted according to the methods outlined by Saldana37 and based upon an expanded set of whole-person domains of the National Consensus Project (NCP) Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care.16 The NCP presented 8 whole-person domains, physical, social, ethical, and other aspects of care, which LifeCourse expanded by adding family/caregiver, financial/legal, and legacy/bereavement domains during development of the broader intervention. The NCP domain “structures and processes of care” did not focus on individualized planning and was not used for this analysis.

The first part of the analysis sought to operationalize the whole-person domains by developing code definitions. First, each researcher independently coded 25% of the data and developed a definition for each code based upon their review. All researchers compared coding associated with each domain until consensus on definitions for each code was achieved.

Second, 2 researchers (S.E.S. and E.W.A.) independently coded 100% of the data using the established code definitions and met to resolve discrepancies. The primary source of information examined for coding was the “description” field in the flow sheet. The “plan” field was used when “description” did not include enough information to enable coding to a specific domain(s). While resolving discrepancies, researchers identified 3 additional domains that resulted in 13 unique definitions and domains (Table 2). Ten domains described aspects of whole person. Simultaneous coding was avoided.37 Goals reflecting 2 or more whole-person domains were coded as “multiple.” An additional domain identified as “housing” was derived using an eclectic coding37 approach that reflected complex meanings expressed by patients about a strong desire or a sense of importance about where, how, and with whom patients wanted to live. Finally, we identified broad goals or aspirations, coded as “global.” Each domain was then categorized and grouped according to themes.

Table 2.

Definitions of Whole-Person Domains.

| Domain Node | Definition |

|---|---|

| Care at the end of life (EOL) | Preparing, recognizing, and then engaging in the final stage of life for the dying and their loved ones; recognizing and anticipating EOL concerns, fears, care needs, preferences, planning, and EOL closure |

| Cultural | Who you are, where you come from, where you have been/what has shaped you, and what is important to you, and how you interact with others |

| Ethical | Includes values, norms, moral principles, and rules of conduct and also ethical conflicts that occur between individuals. Example: advance care planning and interpreting advanced directives |

| Family/caregiver | Any group of people related biologically, emotionally, or legally: the group of people (outside of the medical team) the patient defines as significant for his or her well-being. Example: reference to family conversations |

| Financial/legal | Money and finances that affect living with illness. Legal actions, including making financial wills and durable power of attorney |

| Housing | Staying in own home or moving to a facility or another level of care |

| Legacy/bereavement | The value(s) or meaning(s) of one’s life passed from one to another. The period of mourning and grief experienced following the death of a loved one |

| Physical | Physical symptoms and comfort, functional status and safety, and understanding of illness and treatment plan. Example: symptom or medication review |

| Psychological | Individual adaptation to living with illness, including the presence of strengths, assets, and resources contributing to psychological health. Example: wife needs someone to cover so she feels husband is safe |

| Social | Individual strengths, assets, and connections to social networks and resources. Example: “activities” but not physical activity, social relationships, networks, and resources, not living situation (eg, occupation and work related, hobbies, leisure activities, such as sports) |

| Spiritual/existential | How individuals express meaning, purpose, and connection to others and things. It may or may not involve embracing a particular religious or spiritual identity, affiliation, community, and/or practices |

| Global | Global or broad statements about beliefs, values, and preferences can pertain to multiple domains. What matters most (WMM) statements do not easily lead to a course of action or clear action steps |

| Multiples (2 or more domains) | Pertains to statements that relate to more than 2 whole-person domains |

Results

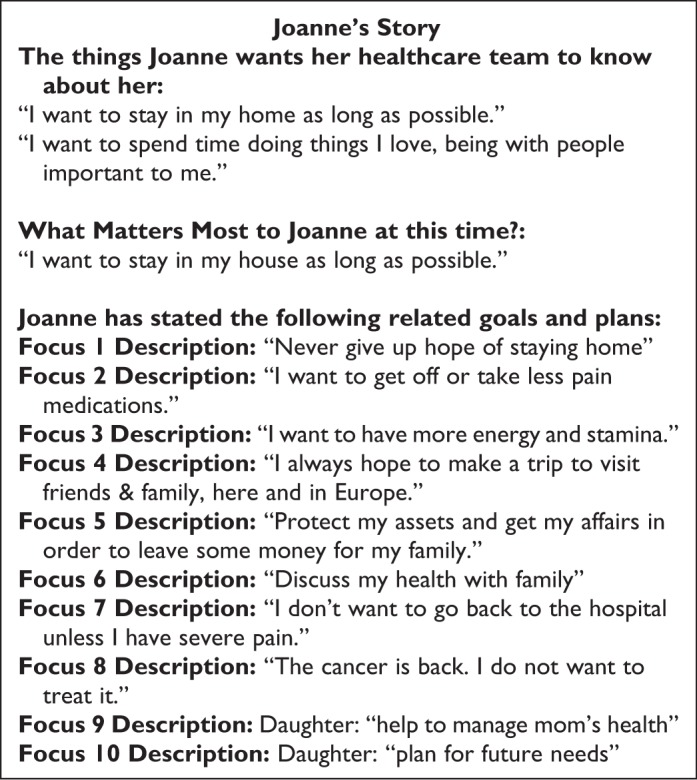

This data set included 999 goal entries. Some goals were repeated over time, averaging 1.83 occurrences per unique goal. Patients expressed a range of 1 to 16 goals each, with an average of 4.2 and a median of 4 goals. We found some goals were repeated with little change to the wording or plan over time, so it was difficult to determine when a goal transitioned to a new focus. Analysis revealed a variety of goal statements categorized into 4 broad themes—medical, nonmedical, multiple, and global. The distribution of goal statements by broad theme was 40% medical goals, 40% nonmedical goals, 16% were a mixture of “multiple” domain goals, and 4% global statements (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of 999 serious illness goals by theme.

Medical goals

Medical goals described activities that promoted change in physical and cognitive well-being or health. Medical goals such as “get through chemotherapy,” “take less medications,” and “manage my blood sugar” were attributed to the physical domain and reflected desires for completing treatment plans to cure or arrest a medical condition. Some goals, such as “reduce Hemoglobin A1c and lower my high blood pressure,” were very specific to controlling and managing medical conditions. Goals related to symptom reduction, such as “I want to breathe better without oxygen,” “resolve facial edema,” and “get rid of the tingling in my arm” revealed patients’ desires to feel better and reduce symptoms. Goals to reduce and/or improve physical or cognitive limitations included “get stronger,” “walk without a cane,” “avoid being in a wheelchair,” and “be less forgetful.” Some medical goals had 2 physical foci; for example, “I want to lose weight so I can breathe better” and “I want to improve my appetite, eat more so I can take chemo.”

Nonmedical goals

There were almost as many nonmedical goals as physical goals. Nonmedical goals reflected other aspects of whole person and were coded in terms of the following domains—social (9%), ethical (7%), family/caregiver (6%), financial/legal (5%), psychological (5%), housing (3%), legacy/bereavement (3%), care at the EOL (1%), spiritual (1%), and culture (0%). Although these goals were not individually as prevalent as medical goals, each domain ended up having specific themes identified. The following analysis includes the findings within each nonmedical domain node.

Social goals included activities focused on connecting to others (eg, “getting Internet to email,” “get a phone in my room,” and “go on a fishing trip in Canada”); giving back to others (eg, “volunteer for AARP [American Association of Retired Persons]” and “volunteer for others with heart failure”); maintaining vocational activities and hobbies (eg, writing, woodworking, quilting, and sewing); and accessing resources and support (eg, “get medications and food delivered” and “apply for metro mobility”).

Ethical goal statements reflected ACP activities, such as completing a health-care directive and changing health-care agent, “I’d like to have a health-care directive.” Family/caregiver goals focused on getting support and resources for family/caregivers (eg, “My daughter and I need some support”) and managing relationships (eg, “I want to spend time with family” and “I want to reconcile with my son”).

Financial/legal goals reflected statements about financial security, preparing paperwork for family, and paying for current care needs, such as “have enough money while I am alive and after I die,” “I want to get my affairs in order,” “I want to create a will,” and “pay for medications at a lower cost.” Psychological goal statements focused on activities to change the state of emotional and mental health, such as “I want to keep a positive mental attitude,” “acupuncture for relaxation,” and “I need emotional support to deal with my illness and other concerns.”

Although few, housing goals reflected desires about where, how, and with whom patients wanted to live and the location and type of care for the purpose of preserving independence (eg, “to stay in my home,” “find new housing so…only one more move required”). Housing goals also reflected a desire to live with others and reduce financial and family burden of care (eg, “to decide on a new place to live with my son David” and “…move to a place where there are increasing levels of care…when I need it”).

Legacy/bereavement goals focused on the donation of time and talents, reflection of personal life values and beliefs, and worries or concerns about grief and loss, for example, “I want to complete my novel,” “organize my stuff for my family,” and “I worry about my family being sad after I die.”

The care at the EOL, spiritual, and cultural goals contained the fewest self-defined goals. The EOL goals focused on care options and preparation for the EOL (eg, “explore hospice options and plan for funeral” and “die peacefully—die in my sleep”). Goals reflecting spiritual activities were about staying connected to a spiritual community and counseling to support spiritual needs, such as “go to church every week” and “talk with pastor about experience with dementia.” There were no cultural domain goals.

Multiple domain goals were complex and not easily attributed to a single domain leaving 16% coded to 2 or more domains. The majority (11%) of multiple domain goals were coded into the “physical” and to 1 or more nonmedical domains (Figure 2). For example, “I’m hoping to continue feeling well so I can continue playing golf, doing art, attending church, and seeing friends” was coded into both “physical and social” domains. In another example, a patient’s goal focused on physical activities to stay healthy, so he could enjoy life with his wife. The corresponding plan for this goal included additional domains of “family/caregiver, global, and housing” domains (eg, “John (a fictionalized patient name) is, while struggling with his illness, acting as a care giver for his wife who has early stages of dementia.…He is hopeful to continue to live well enough to enjoy life and is prepared to make measured steps…to accommodate that (ie, nursing home, etc).”

The remaining 5% of multiple domain goals reflected a mix of nonmedical goals beyond the “physical” domain and expressed a combination of issues specific to all other domains. For example, the goal “I want to visit my daughter in Chicago” was coded to the “family/caregiver” domain, and because the “plan” for this goal included arranging for dialysis in Chicago and setting up affordable transportation, it was also coded into the “physical, financial/legal, and social” domains. Some “multiple” domain goals included more than 1 focus making it difficult to target a single domain. Goals of this type were coded to all domains represented in both goals (eg, “I want to walk and be more independent to avoid moving to assisted living” was coded into the “physical, global, and housing” domains).

The fourth theme, “global,” included aspirational statements that often conveyed emotions, hope, or meaning and purpose in relation to something bigger than an individual aspect of self (eg, “I want to stay alive” and “I want to see my grandchildren grow up”). Global statements usually had no desired plan or identified actions attached to them (eg, “I want to wake up and breathe”). In the absence of an attached plan, “global” goals described a broader sense of meaning and hope, such as “I want to feel alive every day.” “Global” statements focused on living a healthy lifestyle, living longer, emotional or spiritual well-being, relationships, “being normal,” and independence.

Discussion

Movement from problem-oriented disease-specific care implying a desire to be fixed toward goal-oriented care based upon individual desires of health within all aspects of whole person has potential to improve or maintain quality of life when physical decline is inevitable.13 Research results demonstrate that patients express a diverse range of goals related to global aspirations and many facets of the whole person, which patients identify nonmedical goals as often as medical goals. Identification and consideration of medical, nonmedical, multiple, and global goals of serious illness presents an opportunity to individualize assessments and care planning processes.38 Whole-person assessments realign disease-specific goals with views of well-being beyond physical health39 that have been shown to support broader psychosocial needs.7 Care planning and goals of care discussions including self-defined goals can assist in individualizing and setting context to established disease-specific guidelines and assist decision-making that more fully reflect current health status and psychosocial spiritual aspects of patients’ lives.7,40

Integrating nonmedical day-to-day living goals41 is especially relevant for serious illness to sustain a sense of hope and healing when physical decline, cure, or controlling a disease is no longer possible.42,43 Research participants were less likely to identify goals specific to EOL and few had global aspirational goals. Serious illness discussions will miss the psychosocial and emotional issues that help individualize care if providers fail to acknowledge whole-person goals before embarking on disease-specific medical plans and advance directive life-sustaining treatment options. Expanding EOL discussions to include a whole-person approach which includes nonmedical goals may help increase understanding about what is at the heart of patient wishes and individualized care needs.

Advance directive completion is a gold standard to documenting patient goals. The physical decline expected in serious illness increases the potential for goals to change, indicating a need for ongoing conversations which advance directive completion alone cannot support.44,45 This research indicates that it is possible to review and document patient goals beyond ACP and disease-specific interventions and could enable systems that support individualized serious illness care.38 Research findings demonstrated goals articulated by a patient in discussions can be documented in the medical record and made available to other clinicians.

This analysis is a first step to exploring the expressed goals of patients with serious illness and offers a platform for how self-defined goals may be collected and evaluated in generalized palliative care approaches. The results are relevant to a primarily Caucasian group of patients with heart failure, cancer, and dementia, likely in their final 2 to 3 years of life, who received care within a Midwest Health System. These results can inform future research about the goals of a more representative population of patients with serious illness and how patient-defined goals may be collected and used by clinicians.

Patient self-defined goals reveal a rich mix of preferences attributed to medical, nonmedical, multiple, and global goals. When patients living with serious illness are asked what they feel is most important to them, most goals reveal deeper wishes and desires beyond physical needs and express a host of social, ethical, family, psychological, financial, and bereavement needs. Looking further into the relationship between particular goals and more global aspirations may help us better understand what is at the heart of our patients’ wishes in order to receive an individualized care approach.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: From the Robina Foundation.

References

- 1. Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chron Dis Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;11:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(10):1041–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kelley AS. Defining “serious illness”. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(9):985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lynn J, Forlini JH. “Serious and complex illness” in quality improvement and policy reform for end-of-life care. J Gen Intern. Med. 2001;16(5):315–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krahn M, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development. Incorporating patient preferences. JAMA. 2008;300(4):436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fried TF, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O’Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1854–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandsdalen T, Hov R, Hoye S, Rystedt I, Wilde-Larsson B. Patients’ preferences in palliative care: a systematic mixed studies review. Palliat Med. 2015;29(5):399–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty J, Loignon C, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Patient-centered care in chronic disease management: a thematic analysis of the literature in family medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lines LM, Lepore M, Weiner JM. Patient-centered, person-centered, and person-directed care. They are not the same. Med Care. 2015;53(7):561–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hansen E, Walters J, Howes F. Whole person care, patient-centred care and clinical practice guidelines in general practice. Health Sociol Rev. 2016;25(2):157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mold JW, Blake GH, Becker LA. Goal-oriented medical care. Fam Med. 1991;23(1):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rueben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care—an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 3rd ed Pittsburgh, PA: National Concensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Quality Forum (NQF). A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2006. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx. Accessed November 22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. IOM (Institue of Medicine). Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson J, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JPW, et al. Change in end-of-life care for medicar beneficiaries. Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309(5):470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living Well at the End of Life. Adapting Health Care to Serious Chronic Illness in Old Age. SantaMonica, CA: RAND Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fried TR, Tinetti M, Agostini J, Iannone L, Towle V. Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(2):278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Weaver F, et al. Contextual errors and failures in individualizing patient care. A multicenter study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(2):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Quality Forum (NQF). National Quality Partners (NQP): Strategies for Change—A Collabortive Journey to Transform Advanced Illness Care. Washington, DC: NQF; 2016. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Events/Education_Programs/2016/National_Quality_Partners_(NQP)__Strategies_for_Change__A_Collaborative_Journey_to_Transform_Advanced_Illness_Care.aspx. Accessed December 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F-C, Laux JP. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shippee ND, Shippee TP, Mobley PD, Fernstrom KM, Britt HR. Effect of whole-person model of care on patient experience in patients with complex chronic illness in late life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;35(1):104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schellinger S, Cain CL, Shibrowski K, Elumba D, Rosenberg E. Building new teams for late life care: lessons from LifeCourse. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(6):561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walke LM, Byers AL, McCorkle R, Fried TR. Symptom assessment in community-dwelling older adults with advanced chronic disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ho F, Lau F, G. DM, Lesperance M. A reliability and validity study of the palliative performance scale. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7(10):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The mini-cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel A, Parikh R, Howell EH, Hsich E, Landers SH, Gorodeski EZ. Mini-cog performance. Novel marker of post discharge risk among patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(1):8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Briggs L. Shifting focus of advance care planning: using an in-depth interview to build and strengthen relationships. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1233–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Della Santina C, Bernstein RH. Whole-patient assessment, goal planning, and inflection points: their role in achieving quality end-of-life care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):595–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mount BM, Boston PH, Cohen SR. Healing connections: on moving from suffering to a sense of well-being. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):372–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weiner SJ. Contextualizing medical decision to individualize care. Lessons from the qualitative sciences. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MH. Fostering coping and nutruring hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their caregivers. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1965–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mount B. Existential suffering and the determinants of healing. Eur J Palliat Care. 2003;10(2):40–42. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Duggleby WD, Degner L, Williams A, et al. Living with hope: initial evaluation of psychosocial hope intervention for older palliative home care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(3):247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. Br Med J. 2005;330(7498):1007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals. A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]