Abstract

Rationale:

Fracture of the clavicle is a very common injury in children. However, association between clavicle fracture and atlantoaxial rotatory displacement is rarely observed.

Patient concerns:

We present a case of an 8-year-old girl, who suffered a right clavicle fracture as a result of a sledge accident. Six weeks after figure of 8 casting for a right clavicle fracture, an 8-year-old girl was brought to the Pediatric Orthopedic Department due to torticollis.

Diagnoses:

Standard X-ray examination revealed nonunion of the clavicle without any clinical symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) examination was performed and subluxation of cervical vertebrae 1/cervical vertebrae 2 was detected.

Interventions:

The use of Glisson's traction followed by a soft cervical collar resulted in the resolution of all the symptoms. Control CT and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed reduction.

Outcomes:

The patient fully recovered and currently is fully active. The neurological status of the child before and after procedure remained normal.

Lessons:

Clavicle fracture rarely may be associated with atlantoaxial rotatory displacement. Therefore, careful examination including rotation of the neck is necessary to confirm that associations. Moreover, three-dimensional CT scan enables proper spine examination and provides correct diagnosis. As shown in available literature and as well in presented case report, none operative treatment is usually effective.

Keywords: AARD, atlantoaxial rotatory displacement, clavicle fracture

1. Introduction

Fracture of the clavicle is a very common injury in children. Surgical intervention is usually unnecessary. The outcomes of the treatment are satisfactory; after several weeks all symptoms such as pain and deviation of the head disappear. In the last few years, several cases of infrequent but significant association between clavicle fracture and atlantoaxial rotatory displacement (AARD) were reported.[1–3] Subluxation of the cervical spine in children is very rare but sometimes might be lethal.[4] The patient usually suffers from some neurological symptoms and requires surgical stabilization.[5,6]

The fracture is also diagnosed in cases resulting from serious road traffic accidents or during iatrogenic operative procedures under general anesthesia in otolaryngology or when inflammation processes occur.[7] Fracture of the clavicle associated with subluxation of cervical vertebrae 1/cervical vertebrae 2 (C1/C2) is very rare.[3,8] This case report focuses on a clavicle fracture associated with AARD in an 8-year-old girl.

The aim of the paper is to present diagnostic difficulties occurring in the fracture of the clavicle associated with subluxation of C1/C2. The first diagnosis was isolated clavicle fracture and the patient was treated with a figure of 8 cast. Over time the pain disappeared but the wry neck symptoms (torticollis) remained. Facing the clinical features and the fracture union as well as torticollis, the parents came to our clinic for help.

2. A case

The patient was an 8-year-old girl who was admitted to the Pediatric Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Department due to stiffness and left side rotation of the neck and wry neck symptoms accompanying the right clavicle fracture that have sustained over a 6-week period. Right after the incident, the girl was treated by a third party for an isolated clavicles fracture with a figure of 8 cast (Fig. 1). After 6-week treatment, a severe stiffness and wry neck were still present; the patient was referred to our department for a diagnosis. Standard X-ray showed asymptomatic nonunion of the clavicle, the arms had full range of motion with symmetrical muscle force, and the physiological cervical lordosis was flattened (Figs. 2 and 3). Computed tomography (CT) examination with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction was performed and subluxation of C1/C2 was recognized (Figs. 4 and 5).[9–11] Traction harness according to Glisson was used for 8 days and the symptoms of the torticollis subsided. Control CT (Fig. 6) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 7A–C) confirmed reposition. The patient was discharged with the instruction of using a soft cervical collar. After 14-month treatment the patient was fully active and the use of a cervical collar was discontinued. The neurological status of the child before and after treatment remained normal.

Figure 1.

Initial radiograph performed after the injury.

Figure 2.

AP radiograph of the cervical spine performed at time of admission. Visible forced position of the head – torticollis dextra.

Figure 3.

Lateral cervical spine radiograph performed at time of admission. Visible lack of lordosis of the cervical spine.

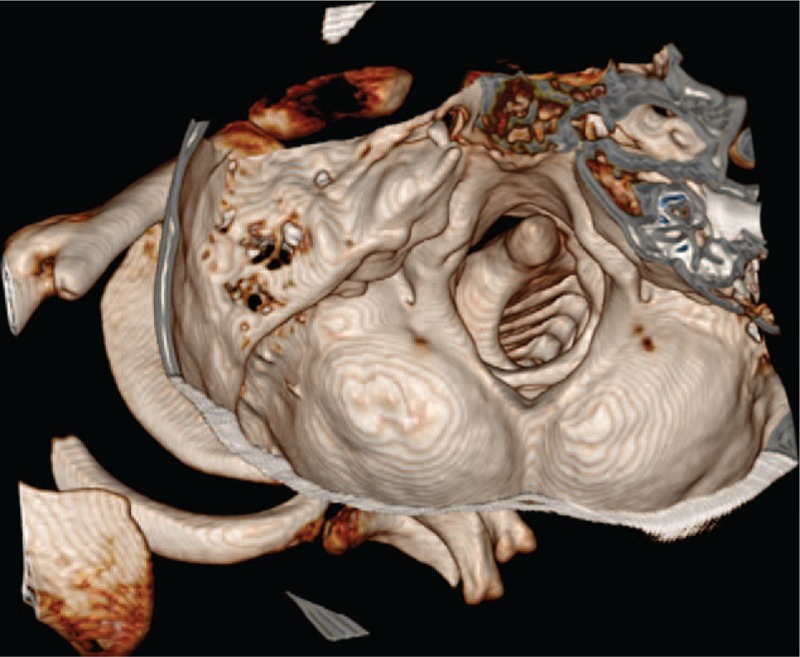

Figure 4.

CT scan confirmed the C1/C2 subluxation.

Figure 5.

3D CT scan of the cervical spine—subluxation of the C1/C2.

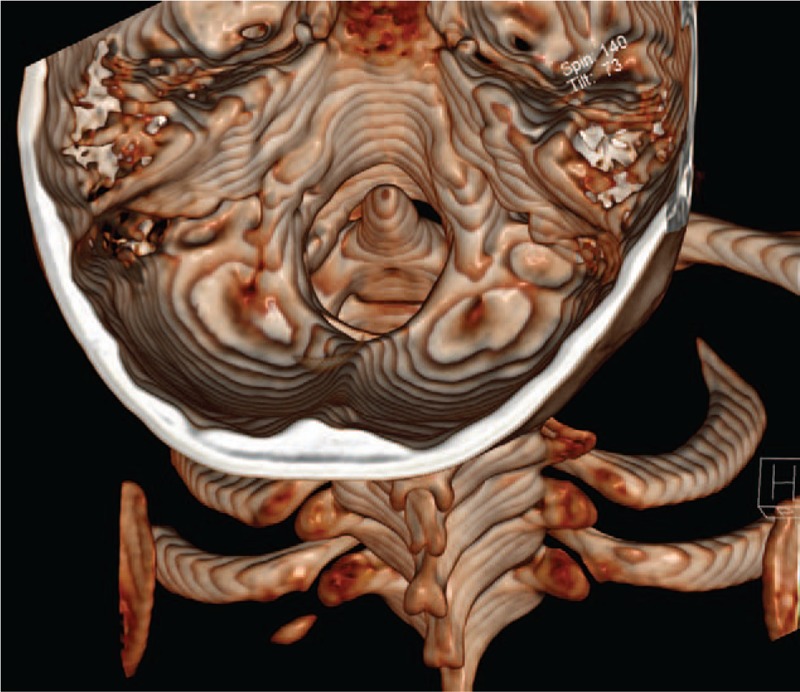

Figure 6.

A follow-up CT examination performed after the treatment confirms proper position of C1/C2.

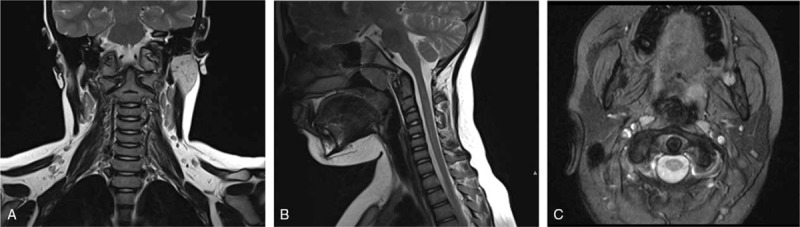

Figure 7.

A follow-up MRI examination performed after the treatment confirms proper position of C1/C2. Images of spinal cord show no signs of myelopathy at the level of former injury (A—coronal view, B—sagittal view, and C—transverse view).

The ethical committee approval was not necessary. Informed consent was given by patient's parents.

3. Discussion

An 8-year-old girl suffered from a right clavicle fracture treated by figure of 8 casting, and 6 weeks after she was brought to the Pediatric Orthopedic Department due to pain of the neck and persistent torticollis. X-ray and CT diagnostics were performed showing union of clavicle fracture, but AARD was recognized. A similar sequence of events is described in the literature.[2,3,6] Corner was the first who in 1907 described the association of AARS and fracture of the clavicle.[3] Boven et al say that most cases occur in girls 6 to 10 years old. In patients the head is laterally bent toward and rotated away from the fractured clavicle.[2] Atlantoaxial rotatory displacement is reported to be rare.[3] Some literature reports that AARD can be sustained during otolaryngology operative procedures under general anesthesia that require head hyperextension.[7] A total of 14 cases of clavicle fractures associated with atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation have been presented in orthopedic surgery. The association of rotatory subluxation of C1/C2 with a clavicular fracture is difficult to appreciate clinically because of the masking of the torticollis by the acute symptoms of the fractured clavicle.[12] Therefore, Nannapaneni et al claim that careful clinical examination would have demonstrated the absence of spasm of the sternomastoid and help heighten suspicion of an associated pathology as the cause of the torticollis.[6]

The prevalence in this group of patient's results from an increased ligamentous laxity linked to estrogen's function. The authors explain the mechanism of subluxation by functional shortening of sternocleidomastoid muscle on the same side as the clavicle fracture and secondary spasm of the muscle which, when accompanied by laxity, can result in AARD.[3,7,13] It is confirmed by rotation of the head away from the clavicle fracture. The diagnosis is made in the following order: first, clavicle fraction, then torticollis with AARD. The delayed in a proper diagnosis is usually caused by severe pain and forced position of the head.[13] The correct diagnosis was made in 7 cases within the first 3 weeks and in the remaining cases between 6 weeks and 3 years after the injury. Prompt diagnosis is crucial for establishing proper treatment regimen. In the cases diagnosed within the first 6 weeks after an injury, merely a soft cervical collar or traction harness according to Glisson was sufficient. Delayed diagnosis can lead to posterior cervical fusion.

4. Conclusions

Clavicle fracture rarely may be associated with AARD. Therefore, careful examination including rotation of the neck is necessary to confirm that associations. Moreover, 3D CT scan enables proper spine examination and provides correct diagnosis. As shown in available literature and as well in presented case report, none operative treatment is usually effective.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 3D CT = three-dimensional reconstruction of computed tomography, AARD = atlanoaxial rotatory displacement, C1/C2 = cervical vertebrae 1/cervical vertebrae 2, CT = computed tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Bagouri E, Deshmukh S, Lakshmanan P. Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation as a cause of torticollis in a 5-year-old girl. BMJ Case Rep 2014;bcr2013202990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bowen Richard E, Mah Jung Y, Otsuka Norman Y. Midshaft clavicle fractures associated with atlantoaxial rotatory displacement: a report of two cases. J Ortho Trauma 2003;17:444–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Goddard NJ, Stabler J, Albert JS. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation and fracture of the clavicle: an association and a classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:72–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Loder RT. Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL. The cervical spine. Lovell and Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics. 4th ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. 748–51. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fielding JW, Hawkins RJ. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation (fixed rotatory subluxation of the atlanto-axial joint). J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nannapaneni R, Nath FP, Papastefanou SL. Fracture of the clavicle associated with a rotatory atlantoaxial subluxation. Injury 2001;32:71–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kawabe N, Hirotani H, Tanaka O. Pathmechanism of atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Niibayashi H. Atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation: a case report. Spine 1998;23:1494–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dvorak J, Hayek J, Zehnder R. CT-functional diagnostics of the rotatory instability of the upper cervical spine: Part 2. An evaluation on healthy adults and patients with suspected instability. Spine 1987;12:726–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fielding JW, Stillwell WT, Chynn KY, et al. Use of computed tomography for the diagnosis of atlanto-axial rotatory fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978;60:1102–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ono K, Yonenobu K, Fuji T, et al. Atlantoaxial rotatory fixation: radiographic study of its mechanism. Spine 1985;10:602–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Al-Etani H, D’Astous J, Letts M, et al. Masked rotatory subluxation of the atlas associated with fracture of the clavicle: a clinical and biomechanical analysis. Am J Orthop 1998;27:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kowalski HM, Cohen WA, Cooper P, et al. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of atlanto-axial rotary subluxation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1987;8:697–702. [Google Scholar]