Abstract

Gap junction channels facilitate the intercellular exchange of ions and small molecules. While this process is critical to all multicellular organisms, the proteins that form gap junction channels are not conserved. Vertebrate gap junctions are formed by connexins, while invertebrate gap junctions are formed by innexins. Interestingly, vertebrates and lower chordates contain innexin homologs, the pannexins, which also form channels, but rarely (if ever) make intercellular channels. While the connexin and the innexin/pannexin polypeptides do not share significant sequence similarity, all three of these protein families share a similar membrane topology and some similarities in quaternary structure. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Gap Junction Proteins edited by Jean Claude Herve.

Keywords: Connexin, Innexin, Pannexin

1. Introduction

Intercellular communication through gap junction channels is critical for coordinating the functions of cells in the tissues of all multicellular organisms by allowing direct exchange of ions and small molecules (including second messengers like Ca2+, IP3 and cyclic nucleotides and oligonucleotides). Gap junction mediated coupling allows groups of cells to respond to a ligand synchronously, even when only a few cells express the ligand receptor. During development, gap junctions form communication compartments in which coupled cells differentiate together, while those that are not coupled acquire a different fate.

2. Connexins

In vertebrates, gap junctions are formed by members of a family of proteins that are called connexins (Cx). Twenty connexins are expressed in humans and in mice (Table 1). The corresponding genes are identified with a symbol starting with “GJ” (for gap junction), while the most commonly used protein nomenclature employs an abbreviation beginning with “Cx” (for connexin) followed by a number corresponding to the molecular mass of the predicted polypeptide in kilodaltons [10]. The connexins form a closely related family exhibiting extensive amino acid identity and similarity within their transmembrane and extracellular domains. The similarities in their extracellular loops can be described by two connexin signatures (PS00407 and PS00408, http://prosite.expasy.org/PDOC00341). Differences and similarities in the connexin sequences have been used to define connexin subfamilies [7,30], and sequence comparisons between different species have been used to identify orthologs [18]. Currently, five connexin subfamilies are recognized (α, β, γ, δ, and ε or GJA, GJB, GJC, GJD, and GJE) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The connexin protein and gene families in humans and mice.

| Human | Mouse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Gene symbol |

Protein name |

Synonyms | Gene symbol |

Protein name |

| GJB1 | CX32 | CMTX1, CMTX | Gjb1 | Cx32 |

| GJB2 | CX26 | DFNB1, DFNA3, NSRD1 | Gjb2 | Cx26 |

| GJB3 | CX31 | DFNA2, EKV | Gjb3 | Cx31 |

| GJB4 | CX30.3 | Gjb4 | Cx30.3 | |

| GJB5 | CX31.1 | Gjb5 | Cx31.1 | |

| GJB6 | CX30 | DFNA3, ED2, EDH, HED | Gjb6 | Cx30 |

| GJB7 | CX25 | – | – | |

| GJA1 | CX43 | ODDD, ODOD, SDTY3 | Gja1 | Cx43 |

| GJA3 | CX46 | CZP3 | Gja3 | Cx46 |

| GJA4 | CX37 | Gja4 | Cx37 | |

| GJA5 | CX40 | Gja5 | Cx40 | |

| – | – | Gja6 | Cx33 | |

| GJA8 | CX50 | CAE1, CZP1, CAE | Gja8 | Cx50 |

| GJA9 | CX59 | – | – | |

| GJA10 | CX62 | Gja10 | Cx57 | |

| GJC1 | CX45 | Gjc1 | Cx45 | |

| GJC2 | CX47 | SPG44 | Gjc2 | Cx47 |

| GJC3 | CX30.2/31.3 | Gjc3 | Cx29 | |

| GJD2 | CX36 | Gjd2 | Cx36 | |

| GJD3 | CX31.9 | Gjd3 | Cx30.2 | |

| GJD4 | CX40.1 | Gjd4 | Cx39 | |

| Gje1 | Cx23 | |||

Modified from Beyer and Berthoud [8] and from http://www.genenames.org/genefamilies/GJ. Cx has been generally used as an abbreviation for Connexin. Many of the synonyms refer to genetic diseases or syndromes linked to mutations of the connexins.

A wide range of genetic diseases have been mapped to mutations of the connexin encoding genes (including deafness, neuropathies, cataracts, skeletal abnormalities, and skin diseases) (reviewed in [9,31,37,38,46,48,53,55]). Connexins have sometimes been identified by abbreviations corresponding to these diseases, such as ODDD (oculodentodigital dysplasia), CMTX (X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease), and Erythrokeratoderma variabilis (EKV). Many of these abbreviations are included as synonyms in Table 1.

The ability of connexins to form intercellular channels is well documented in many different tissues and expression systems. Connexins can also form plasma membrane channels in unapposed cells [36]; these connexin “hemi-channels” have been implicated in a variety of physiological and pathological processes (reviewed in [47]).

3. Innexins

Cell-to-cell junctions and the process of direct intercellular communication are present even in some of the most primitive multicellular organisms [22,23,25,26]. Indeed, some of the first demonstrations of direct intercellular communication came from studies in invertebrates [22]. Although they perform similar functions to their vertebrate counterparts, invertebrate gap junctions are encoded by members of a very different gene family, the innexins (reviewed in [5,42]). The innexins do not exhibit significant sequence similarity to the connexins.

The innexins have been most extensively studied in model organisms like the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), the nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans), and the medicinal leech (Hirudo verbana). Their members are listed in Tables 2–4. Unlike most of the connexin genes (which usually contain the full coding sequence in a single exon), several innexin genes contain the coding region in more than one exon. The number of introns can vary among members of the family (e.g., innexin genes from Hirudo verbana [28] and Drosophila melanogaster [51]). The presence of multiple introns within the DNA encoding the coding region allows the generation of different protein products through alternative RNA splicing (e.g., the Drosophila shak-B locus [17]). Interestingly, the Drosophila melanogaster inx2 gene locus localizes in opposite orientation in the longest intron of the inx7 gene; this structural organization has been proposed to serve for reciprocal control of gene expression of these innexins [16].

Table 2.

Drosophila melanogaster innexins.

| Gene symbol |

Gene name | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| inx2 | Innexin 2 | kropf, prp33, l(1)G0043, l(1)G0035, l(1)G0118 |

| inx3 | Innexin 3 | Dm-Inx3, inx-3 |

| inx5 | Innexin 5 | |

| inx6 | Innexin 6 | prp6 |

| inx7 | Innexin 7 | prp7 |

| ogre | Optic ganglion reduced | 1(1)ogre, inx1 |

| shakB | Shaking B | Pas, shak-B, R-9-29, shB, R9-29, inx8 |

| zpg | Zero population growth | inx4 |

Modified from http://flybase.org/reports/FBgg0000112.html and based on Abascal and Zardoya [1]. These proteins are also identified as Passover protein homologs (http://www.membranetransport.org/other_family.php?fFID=Innexin&oOID=dmel1).

Table 4.

Hirudo verbana innexins.

| Symbol | Name |

|---|---|

| inx1 | Innexin 1 |

| inx2 | Innexin 2 |

| inx3 | Innexin 3 |

| inx4 | Innexin 4 |

| inx5 | Innexin 5 |

| inx6 | Innexin 6 |

| inx7 | Innexin 7 |

| inx8 | Innexin 8 |

| inx9A | Innexin 9A |

| inx9B | Innexin 9B |

| inx10 | Innexin 10 |

| inx11A | Innexin 11A |

| inx11B | Innexin 11B |

| inx12 | Innexin 12 |

| inx13 | Innexin 13 |

| inx14 | Innexin 14 |

| inx15 | Innexin 15 |

| inx16 | Innexin 16 |

| inx17 | Innexin 17 |

| inx18 | Innexin 18 |

| inx19 | Innexin 19 |

Based on Kandarian et al. [28].

Like the connexins, the innexins are expressed with overlapping patterns allowing the formation of heteromeric hemichannels and heterotypic gap junction channels. Their wide expression in many different tissues reflects their involvement in many different cellular processes. Studies of innexins in invertebrates have particularly emphasized the importance of innexins in the nervous system. Many different innexins are expressed in the nervous system of invertebrates (at least 15 in the leech [28] and 8 in the octopus [2]). Mutations of some invertebrate innexins cause characteristic behavioral changes like shaking mutants in Drosophila melanogaster and uncoordinated mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans (reviewed in [42]). Innexins are differentially expressed during development [20]. The spatial and temporal expression differences may establish communication compartments that contribute to developmental patterning [45,54].

4. Pannexins

Surprisingly, genes and expressed transcripts with substantial sequence similarity to the invertebrate innexins have also been identified in vertebrates [35]. These genes and proteins are called pannexins [35]. Three different pannexins are expressed in human and mouse tissues (Table 5). For human PANX2, two mRNA variants have been reported that encode proteins with different C-terminal amino acids (loci, NM_001160300.1 and NM_052839.3).

Table 5.

Pannexins.

| Symbol | Name | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| PANX1 | Pannexin 1 | MRS1, UNQ2529, PX1 |

| PANX2 | Pannexin 2 | hPANX2, PX2 |

| PANX3 | Pannexin 3 | Px3 |

Like the connexins, the pannexins form oligomeric polypeptide assemblies and traffic to the plasma membrane, where they can form channels that connect the cytoplasm to the extracellular space [13]. Although PANX1 can form functional gap junction channels when expressed in Xenopus oocytes [13], pannexins do not form intercellular channels in transfected mammalian cells [50].

Unlike the connexins, pannexins undergo glycosylation within their extracellular regions. This modification may be important for the targeting of pannexins to the plasma membrane [11,39]. Pannexin glycosylation may effectively impede cell-to-cell channel formation and regulate pannexin intermixing [40]. Some innexins may also be glycosylated; for example, two yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) innexins (AeInx3 and AeInx7) contain predicted N-glycosylation sites, and immunoblots of AeInx3 show multiple immunoreactive bands. This similarity to the pannexins suggests that some innexins might have other functional roles besides intercellular communication [15].

Pannexins have been implicated in several pathologies including cardiovascular diseases, inflammation, cancer and neuropathies [6,41,57]. Due to their wide expression in many tissues and organs, deleterious pannexin gene mutations might be expected. The only human gene mutation reported to date encodes a non-functional PANX1 variant that does not inhibit the function of wild type PANX1; it was found in a patient (homozygous for this allele) with disorders in several organs [49]. Investigations of pannexin-null mice have also implicated pannexins in contributing to protection from ischemic stroke injury [4,21], modulation of neuronal excitability and learning [43,44], bone development [27], narcotic withdrawal [14], and sleep-wake cycle regulation and behavior [29].

5. Shared features of connexins, innexins, and pannexins

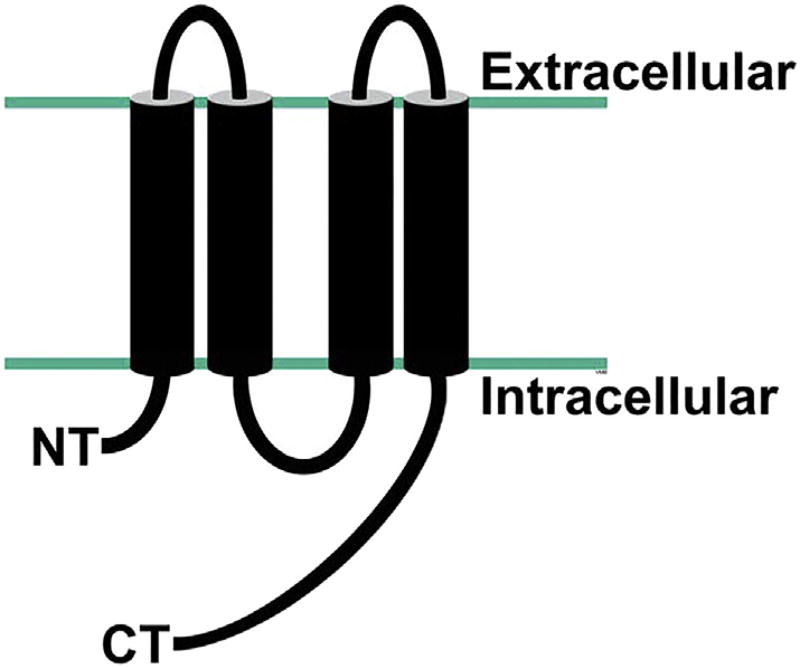

Despite their lack of amino acid sequence similarities, the connexins and the innexins/pannexins share structural and functional commonalities. All of these genes encode polytopic membrane proteins that have similar topologies within the membrane (Fig. 1). They each contain four transmembrane domains with their N- and C-termini on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, leading to the formation of two extracellular loops and one intracellular loop. The connexin topologies were originally predicted from hydropathy plots of the cloned sequences and supported by mapping of regions using site-directed antibodies [24,56]. Determination of the crystal structures of some connexins and innexins supported the topological models [32,33,34,52]. Studies confirm that connexins, pannexins and innexins form channels with similar quaternary structures [3,12,19,32,33,52]. However, while connexin hemi-gap junction channels contain 6 subunits regardless of the connexin isoform, innexin hemi-gap junction channels and pannexin channels can have 6 or 8 subunits depending on the isoform (e.g. C. elegans inx-6 forms octamers, rat Panx1 forms hexamers and rat Panx2 most likely forms octamers) [3,33,34].

Fig. 1.

Membrane topology of a connexin/innexin/pannexin. Transmembrane domains are depicted as cylinders that span the plasma membrane (boundaries indicated by teal lines). NT, N-terminus; CT, C-terminus.

The connexins, innexins and pannexins all contain cysteines in their extracellular loops, but they differ in the numbers of cysteines in each loop: connexins contain three, whereas innexins and pannexins contain two. The connexins, innexins and pannexins contain an invariant proline residue in the second transmembrane domain. This proline forms part of a motif (PXXXW) that is conserved between vertebrate pannexins and most innexins. The connexins, innexins, and pannexins are all multi-member families; within the families, sequence differences between members confer unique channel and regulatory properties.

Both connexins and pannexins participate in several processes including propagation of calcium waves, inflammation, memory consolidation and neurodegeneration. Knowledge of the sequences and structures of the connexins, pannexins, and innexins is facilitating elucidation of their individual, shared, and complementary roles in physiology and pathophysiology.

Table 3.

Caenorhabditis elegans innexins.

| Locus | Sequence | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| inx-1 | C16E9.4 | CELE_C16E9.4, opu-1, pcr55 |

| inx-2 | F08G12.10 | CELE_F08G12.10, XL914, opu-2 |

| inx-3 | F22F4.2 | opu-3, CELE_F22F4.2 |

| inx-5 | R09F10.4 | CELE_R09F10.4, opu-5 |

| inx-6 | C36H8.2 | CELE_C36H8.2, opu-6 |

| inx-7 | K02B2.4 | CELE_K02B2.4, opu-7 |

| inx-8 | ZK792.2 | opu-8, CELE_ZK792.2 |

| inx-9 | ZK792.3 | opu-9, CELE_ZK792.3 |

| inx-10 | T18H9.5 | opu-10, CELE_T18H9.5 |

| inx-11 | W04D2.3 | CELE_W04D2.3, opu-11 |

| inx-12 | ZK770.3 | opu-12, let-368, CELE_ZK770.3 |

| inx-13 | Y8G1A.2 | CELE_Y8G1A.2, let-585, opu-13 |

| inx-14 | F07A5.1 | CELE_F07A5.1, opu-14 |

| inx-15 | R12E2.9 | opu-15, CELE_R12E2.9 |

| inx-16 | R12E2.5 | CELE_R12E2.5, opu-16 |

| inx-17 | R12E2.4 | opu-17, CELE_R12E2.4, 1E733 |

| inx-18 | C18H7.2 | opu-18, CELE_C18H7.2 |

| inx-19 | T16H5.1 | nsy-5, CELE_T16H5.1, opu-19 |

| inx-20 | T23H4.1 | CELE_T23H4.1, opu-20 |

| inx-21 | Y47G6A.1 | CELE_Y47G6A.1, opu-21 |

| inx-22 | Y47G6A.2 | CELE_Y47G6A.2 |

| unc-9 | R12H7.1 | CELE_R12H7.1 |

| unc-7 | R07D5.1 | unc-124, unc-12, CELE_R07D5.1 |

| eat-5 | F13G3.8 | CELE_F13G3.8 |

| che-7 | F26D11.10 | inx-4, CELE_F26D11.10 |

Modified from http://www.wormbase.org/resources/gene_class/inx#01–10, http://www.wormbase.org/species/c_elegans/gene/WBGene00006749#0-9g-3, http://www.wormbase.org/species/c_elegans/gene/WBGene00006747#0-9g-3, http://www.wormbase.org/species/c_elegans/gene/WBGene00001136#0-9g-3, and http://www.wormbase.org/species/c_elegans/gene/WBGene00000488#0-9g-3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant EY08368.

Footnotes

Transparency Document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- 1.Abascal F, Zardoya R. Evolutionary analyses of gap junction protein families. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertin CB, Simakov O, Mitros T, Wang ZY, Pungor JR, Edsinger-Gonzales E, Brenner S, Ragsdale CW, Rokhsar DS. The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties. Nature. 2015;524:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature14668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrosi C, Gassmann O, Pranskevich JN, Boassa D, Smock A, Wang J, Dahl G, Steinem C, Sosinsky GE. Pannexin1 and Pannexin2 channels show quaternary similarities to connexons and different oligomerization numbers from each other. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:24420–24431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bargiotas P, Krenz A, Hormuzdi SG, Ridder DA, Herb A, Barakat W, Penuela S, von Engelhardt EJ, Monyer H, Schwaninger M. Pannexins in ischemia-induced neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:20772–20777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018262108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer R, Loer B, Ostrowski K, Martini J, Weimbs A, Lechner H, Hoch M. Intercellular communication: the Drosophila innexin multiprotein family of gap junction proteins. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begandt D, Good ME, Keller AS, DeLalio LJ, Rowley C, Isakson BE, Figueroa XF. Pannexin channel and connexin hemichannel expression in vascular function and inflammation. BMC Cell Biol. 2017;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s12860-016-0119-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12860-016-0119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett MVL, Barrio LC, Bargiello TA, Spray DC, Hertzberg E, Sáez JC. Gap junctions: new tools, new answers, new questions. Neuron. 1991;6:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90241-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. The family of connexin genes. In: Harris A, Locke D, editors. Connexins: A Guide. Humana Press; New York: 2009. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer EC, Ebihara L, Berthoud VM. Connexin mutants and cataracts. Front. Pharmacol. 2013;4:43. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00043. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2621–2629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boassa D, Ambrosi C, Qiu F, Dahl G, Gaietta G, Sosinsky G. Pannexin1 channels contain a glycosylation site that targets the hexamer to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:31733–31743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan MJ, Karcz J, Vaughn NR, Woolwine-Cunningham Y, De Priest AD, Escalona Y, Perez-Acle T, Skerrett IM. Tryptophan scanning reveals dense packing of connexin transmembrane domains in gap junction channels composed of connexin32. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:17074–17084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.650747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruzzone R, Hormuzdi SG, Barbe MT, Herb A, Monyer H. Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burma NE, Bonin RP, Leduc-Pessah H, Baimel C, Cairncross ZF, Mousseau M, Shankara JV, Stemkowski PL, Baimoukhametova D, Bains JS, Antle MC, Zamponi GW, Cahill CM, Borgland SL, De KY, Trang T. Blocking microglial pannexin-1 channels alleviates morphine withdrawal in rodents. Nat. Med. 2017;23:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nm.4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calkins TL, Woods-Acevedo MA, Hildebrandt O, Piermarini PM. The molecular and immunochemical expression of innexins in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti: insights into putative life stage- and tissue-specific functions of gap junctions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;183:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiusano ML, Giaimo RD, Potenza N, Russo GMR, Geraci G, del Gaudio R. A possible flip-flop genetic mechanism for reciprocal gene expression. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4919–4922. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crompton D, Todman M, Wilkin M, Ji S, Davies J. Essential and neural transcripts from the Drosophila shaking-B locus are differentially expressed in the embryonic mesoderm and pupal nervous system. Dev. Biol. 1995;170:142–158. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruciani V, Mikalsen SO. The vertebrate connexin family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:1125–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5571-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DePriest A, Phelan P, Skerrett IM. Tryptophan scanning mutagenesis of the first transmembrane domain of the innexin Shaking-B(Lethal) Biophys. J. 2011;101:2408–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dykes IM, Macagno ER. Molecular characterization and embryonic expression of innexins in the leech Hirudo medicinalis. Dev. Genes Evol. 2006;216:185–197. doi: 10.1007/s00427-005-0048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freitas-Andrade M, Bechberger JF, MacVicar BA, Viau V, Naus CC. Pannexin1 knockout and blockade reduces ischemic stroke injury in female, but not in male mice. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16937. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Furshpan EJ, Potter DD. Transmission at the giant motor synapses of the crayfish. J. Physiol. 1959;145:289–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilula NB, Satir P. Septate and gap junctions in molluscan gill epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 1971;51:869–872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.3.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodenough DA, Paul DL, Jesaitis L. Topological distribution of two connexin32 antigenic sites in intact and split rodent hepatocyte gap junctions. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1817–1824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hand AR, Gobel S. The structural organization of the septate and gap junctions of Hydra. J. Cell Biol. 1972;52:397–408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.52.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudspeth AJ, Revel JP. Coexistence of gap and septate junctions in an invertebrate epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 1971;50:92–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishikawa M, Williams GL, Ikeuchi T, Sakai K, Fukumoto S, Yamada Y. Pannexin 3 and connexin 43 modulate skeletal development through their distinct functions and expression patterns. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:1018–1030. doi: 10.1242/jcs.176883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandarian B, Sethi J, Wu A, Baker M, Yazdani N, Kym E, Sanchez A, Edsall L, Gaasterland T, Macagno E. The medicinal leech genome encodes 21 innexin genes: different combinations are expressed by identified central neurons. Dev. Genes Evol. 2012;222:29–44. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0387-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovalzon VM, Moiseenko LS, Ambaryan AV, Kurtenbach S, Shestopalov VI, Panchin YV. Sleep-wakefulness cycle and behavior in pannexin1 knockout mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2017;318:24–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar NM, Gilula NB. Molecular biology and genetics of gap junction channels. Semin. Cell Biol. 1992;3:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4682(10)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JR, White TW. Connexin-26 mutations in deafness and skin disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009;11:e35. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1462399409001276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda S, Nakagawa S, Suga M, Yamashita E, Oshima A, Fujiyoshi Y, Tsukihara T. Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 Å resolution. Nature. 2009;458:597–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makowski L, Caspar DLD, Phillips WC, Goodenough DA. Gap junction structures: analysis of the X-ray diffraction data. J. Cell Biol. 1977;74:629–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.2.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshima A, Matsuzawa T, Murata K, Tani K, Fujiyoshi Y. Hexadecameric structure of an invertebrate gap junction channel. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S. A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:R473–R474. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul DL, Ebihara L, Takemoto LJ, Swenson KI, Goodenough DA. Connexin46, a novel lens gap junction protein, induces voltage-gated currents in nonjunctional plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:1077–1089. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paznekas WA, Boyadjiev SA, Shapiro RE, Daniels O, Wollnik B, Keegan CE, Innis JW, Dinulos MB, Christian C, Hannibal MC, Jabs EW. Connexin 43 (GJA1) mutations cause the pleiotropic phenotype of oculodentodigital dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:408–418. doi: 10.1086/346090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paznekas WA, Karczeski B, Vermeer S, Lowry RB, Delatycki M, Laurence F, Koivisto PA, Van Maldergem L, Boyadjiev SA, Bodurtha JN, Wang JE. GJA1 mutations, variants, and connexin 43 dysfunction as it relates to the oculodentodigital dysplasia phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:724–733. doi: 10.1002/humu.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penuela S, Bhalla R, Gong X-Q, Cowan KN, Celetti SJ, Cowan BJ, Bai D, Shao Q, Laird DW. Pannexin 1 and pannexin 3 are glycoproteins that exhibit many distinct characteristics from the connexin family of gap junction proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3772–3783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penuela S, Bhalla R, Nag K, Laird DW. Glycosylation regulates pannexin intermixing and cellular localization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4313–4323. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penuela S, Harland L, Simek J, Laird DW. Pannexin channels and their links to human disease. Biochem. J. 2014;461:371–381. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phelan P. Innexins: members of an evolutionarily conserved family of gap-junction proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1711:225–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prochnow N, Abdulazim A, Kurtenbach S, Wildforster V, Dvoriantchikova G, Hanske J, Petrasch-Parwez E, Shestopalov VI, Dermietzel R, Manahan-Vaughan D, Zoidl G. Pannexin1 stabilizes synaptic plasticity and is needed for learning. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051767. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Retamal MA, Alcayaga J, Verdugo CA, Bultynck G, Leybaert L, Sáez PJ, Fernández R, León LE, Sáez JC. Opening of pannexin- and connexin-based channels increases the excitability of nodose ganglion sensory neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:158. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00158. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruangvoravat CP, Lo CW. Restrictions in gap junctional communication in the Drosophila larval epidermis. Dev. Dyn. 1992;193:70–82. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001930110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabag AD, Dagan O, Avraham KB. Connexins in hearing loss: a comprehensive overview. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2005;16:101–116. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2005.16.2-3.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sáez JC, Leybaert L. Hunting for connexin hemichannels. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scherer SS, Kleopa KA. X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2012;17(Suppl. 3):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shao Q, Lindstrom K, Shi R, Kelly J, Schroeder A, Juusola J, Levine KL, Esseltine JL, Penuela S, Jackson MF, Laird DW. A germline variant in the PANX1 gene has reduced channel function and is associated with multisystem dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:12432–12443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.717934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sosinsky GE, Boassa D, Dermietzel R, Duffy HS, Laird DW, Macvicar B, Naus CC, Penuela S, Scemes E, Spray DC, Thompson RJ, Zhao HB, Dahl G. Pannexin channels are not gap junction hemichannels. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:193–197. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.3.15765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stebbings LA, Todman MG, Phillips R, Greer CE, Tam J, Phelan P, Jacobs K, Bacon JP, Davies JA. Gap junctions in Drosophila: developmental expression of the entire innexin gene family. Mech. Dev. 2002;113:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Yeager M. Three-dimensional structure of a recombinant gap junction membrane channel. Science. 1999;283:1176–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Steensel MA. Gap junction diseases of the skin. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004;131C:12–19. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warner AE, Lawrence PA. Permeability of gap junctions at the segmental border in insect epidermis. Cell. 1982;28:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wingard JC, Zhao HB. Cellular and deafness mechanisms underlying connexin mutation-induced hearing loss – a common hereditary deafness. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:202. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00202. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2015.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yancey SB, John SA, Lal R, Austin BJ, Revel J-P. The 43-kD polypeptide of heart gap junctions: immunolocalization, topology, and functional domains. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:2241–2254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yanguas SC, Willebrords J, Johnstone SR, Maes M, Decrock E, De BM, Leybaert L, Cogliati B, Vinken M. Pannexin1 as mediator of inflammation and cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1864:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]