Abstract

Purpose

There is no consensus on what constitutes adequate negative margins in breast-conserving therapy (BCT). We systematically review the evidence on surgical margins in BCT for invasive breast cancer to support the development of clinical guidelines.

Methods

Study-level meta-analysis of studies reporting local recurrence (LR) data relative to final microscopic margin status and the threshold distance for negative margins. LR proportion was modeled using random-effects logistic meta-regression.

Results

Based on 33 studies (LR in 1,506 of 28,162) the odds of LR were associated with margin status [model 1: OR=1.96 for positive/close vs negative; model 2: OR=1.74 for close vs negative, 2.44 for positive vs negative; (P<0.001 both models)] but not with margin distance [model 1: >0mm vs 1mm(referent) vs 2mm vs 5mm (P=0.12); and model 2: 1mm vs 2mm vs 5mm (P=0.90)], adjusting for study median follow-up time. There was little to no evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the distance for declaring negative margins increased, adjusting for follow-up time [model 1: 1mm (OR=1.0, referent), 2mm (OR=0.95), 5mm (OR=0.65), P=0.21 for trend; and model 2: 1mm (OR=1.0, referent), 2mm (OR=0.91), 5mm (OR=0.77), P=0.58 for trend]. Adjustment for covariates such as use of endocrine therapy, or median-year of recruitment, did not change the findings.

Conclusions

Meta-analysis confirms that negative margins reduce the odds of LR however increasing the distance for defining negative margins is not significantly associated with reduced odds of LR, allowing for follow-up time. Adoption of wider relative to narrower margin widths to declare negative margins is unlikely to have a substantial additional benefit for long-term local control in BCT.

Keywords: breast cancer, margins, local recurrence, breast-conserving therapy, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Both tumour burden and tumour biology contribute to clinical outcomes in breast cancer (BC). The effectiveness of breast-conserving therapy (BCT) [breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and radiation therapy] for local treatment of invasive BC is well established.1–6 Adequate local control has been shown to confer a survival benefit at long-term follow-up.6 BCS aims to achieve a balance between complete resection of the tumour, and avoiding excessive resection of breast tissue to provide a good cosmetic outcome.7,8 Many tumour and therapeutic factors influence the risk of local (in-breast) recurrence (LR) after BCT for invasive BC6–12, including the status of surgical margins.9,10

There is consensus that the risk of LR is increased if the surgical margins are positive (ink on tumour cells at the resection margin)8,10,12,13 although estimates of effect vary between studies. However, to date, there is no consensus on what constitutes an adequate negative margin for BCS.12–17 Lack of consensus on this issue is reflected in variations in practice amongst clinicians, countries, and clinical guidelines11,17–19, with the net result that re-excision to achieve more widely clear margins is commonly performed.18,20

In this work, we extend our previous systematic review on margins10 to provide an updated summary of the evidence on the association between tumour margins in invasive BC and LR, to support the development of consensus guidelines. Using study-level meta-analysis, the evidence on surgical margins in women with early-stage invasive BC treated with BCT was systematically examined to (a) estimate the effect of microscopic margin status on LR, (b) examine the effect of various thresholds to define negative (and relative positive or close) margins, and (c) discuss whether a minimum negative distance or width can be defined for margins in relation to maximising local control.

METHODS

The methodology used in this systematic review was based on published work from Houssami et al10, and will be described relatively briefly.

Criteria for Study Eligibility

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported data allowing calculation of the proportion of LR in relation to margin status and the threshold width or distance used to declare a negative margin, and where the following pre-defined criteria10 were also met: (1) subjects had early-stage invasive BC (clinical or pathological stages I and II in at least 90%); (2) treatment consisted of BCT [BCS and whole-breast radiotherapy (WBR)]; (3) reported quantitatively-defined microscopic margins where negative margins, and relatively positive and/or close margins, were defined in terms of a threshold distance or width from the cut edge of the specimen (exception noted below); (4) provided age data; and (5) had a minimum median or mean follow-up time of 4 years.

Studies reporting LR without quantifying margins, or where all subjects had the same margin status, or using non-standard or unclear margin definitions, or limited to small subgroups, were ineligible. For the updated meta-analysis, we also considered studies that did not declare a quantified distance for negative margins (hence not meeting criterion number 3) provided that the information in the study allowed classification of negative margins as above 0 mm; however, these studies were not included in trend analysis for negative margin distance. Authors were contacted for clarification or for further information on definitions and/or data where necessary.

Study eligibility criteria considered epidemiological principles in evaluating prognostic studies10 – specifically, that subjects were assembled at a relatively common point in the course of disease, and that adequate follow-up time was allowed for clinical endpoints to have occurred.21,22 Therefore, eligibility criteria for this review integrated cancer stage and a minimum follow-up time as a quality filter, and required final microscopic margins and WBR as inclusion criteria to reflect standards of care. Additional information to help characterize and appraise eligible studies was extracted including design, population characteristics, follow-up, margin assessment, and treatment-related variables. These were partly adapted from a framework21 and recommendations22 for assessing the internal validity of studies dealing with prognosis in meta-analysis.

Literature Search & Data Extraction

A systematic literature search was conducted [MEDLINE and EBM reviews, 1965 to May 2010 (initial search); Medline search updated at January 2013] for primary studies that met eligibility criteria, using the search and study identification strategy summarised in Online-Appendix 1. One investigator (NH) screened abstracts identified in the literature search (n = 870) and full-text of potentially relevant studies (n= 115). Data from eligible studies (n =33)23–55 were extracted independently by two investigators (NH, MLM for updated data extraction; or as previously described10) using pre-defined data forms. The search strategy and identification of eligible studies (including information on related studies56–66 and excluded studies67–89) are presented in Online-Appendix 1. Where two or more papers reported the same cohort, the most recent study (that provided margin-specific LR data) was preferentially used to minimize duplicate data – additional details in Online-Appendix 1.

Extracted Variables

Descriptive and quantitative data were extracted from each study for the following: margin definition and categories, LR definition and outcomes data, duration of (and losses to) follow-up, years of study recruitment, study design, age, stage (distribution, node status, aggregate tumour size), surgery including re-excision, radiation therapy [WBR dose, boost (proportion given boost and dose), total dose to tumor bed, node irradiation], systemic therapy (endocrine or chemotherapy use), hormone receptors, tumor grade, lympho-vascular invasion (LVI), and extensive intraductal component (EIC). We did not collect the following variables (HER2 status, histology distribution) because our prior data extractions indicated that few studies reported these variables.

Definitions of Variables

Margins

Study-specific information on the definition of the final microscopic margins, from excision or re-excision, was extracted based on margin status (whether negative, close or positive) and margin distance (the width used as the threshold for declaring negative margins relative to positive or close). To standardize synthesis of the evidence on microscopic margins, we considered a standard classification for positive margins to be the presence of (invasive or in-situ) cancer at the transected or inked margin. Negative margins were defined as the absence of tumour within a specified distance (mm) of the resection margin, with a close margin indicating presence of tumour within that distance but not at the resection margin. Studies reporting margin distance for negative relative to positive (without differentiating close from positive) were also considered. To allow for variable classification of margins across studies, two models were developed (see also Analysis): model 1 included all studies, combining positive and close (because some studies did not distinguish between these categories or did not report LR data separately for positive and close) in comparison with negative; and model 2 included studies allowing comparisons across the three categories positive, close and negative.

Where an unknown margin category was reported, this was generally due to: specimen not being inked, specimen fragmented or removed in pieces; microscopic margins not given in the pathology report; or specimen not available (in studies where specimens were reviewed38,40,42,47,49). Since the unknown category cannot contribute meaningful data on the effect of margins, it has not been included in our models however data for this category were included in descriptive analyses.

Local Recurrence (LR)

Definition and data for LR as end-point was classified into 2 categories: LR (first), for studies reporting LR as the first site of relapse (including studies where LR may have occurred alone or simultaneously with regional and/or distant relapse); and LR (any), for studies reporting LR occurring at any time (including LR as the first site of relapse or concurrent with or after regional or distant relapse, or LR not further specified).

Covariates

Extracted variables were classified based on quantitative data; additional information was categorized for stage, surgery, and losses to follow-up, for analytic purposes. Studies were classified into two categories for stage:(1) all subjects had stage I-II BC; or (2) ≥ 90% of subjects were estimated to have had stage I-II BC, based on reported stage-distribution, or derived from tumor-size and node data distribution. Therefore, category 2 studies included some stage 0 (DCIS), stage III or stage unknown in <10% of subjects. Studies reporting quadrantectomy32,35,38,40,41,43,48,50,54 in some subjects were also examined separately. Studies reporting information on losses to follow-up were compared with those not reporting any information on this variable.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to examine the distribution of study-level variables. For continuous measures, the median, range, and inter-quartile range (IQR) were calculated. The proportion of women who had a LR was modeled using random effects logistic meta-regression. Random study effects were included in all models to allow for anticipated heterogeneity between studies beyond what would arise from within study sampling error alone. Taking account of both within, and between study variability provides valid standard errors, confidence intervals, and P-values. Statistical significance was set at P <0.05 (two-sided); P <0.1 was considered as weak evidence of association for analysis of covariates (see below).

Modeling was used to assess whether the odds of LR were associated with margin status and distance, adjusted for study-specific median follow-up time (given that risk of LR is known to increase with longer follow-up time and based on evidence of association in our prior and present meta-analysis). Margin status and distance were tested for interaction. Each covariate was fitted both univariately (in a model that did not include margins), and also jointly with margin status and distance, and study median follow-up time (adjusted models). Study-specific median age and median follow-up time were fitted as continuous variables. Covariates that showed at least a weak association (P<0.1) with LR either univariately or in the adjusted models were further examined and reported in the models; LR type was also included in modeling based on clinical relevance. Covariates reported in less than half of studies were not considered reliable for modeling.

In Model 1, margin status was fitted as a dichotomous variable (positive/close vs negative) and distance was fitted as a categorical variable (>0mm vs1mm vs 2mm vs 5mm), using 1mm as the referent category. Each model was refitted to test for trend across distance categories (coded as 1, 2, 3) by treating the categories as equally spaced on a continuous scale, after excluding the group >0mm (because the order of this group on a continuous scale cannot be definitively determined). In Model 2, margin status was fitted as three categories: positive vs close vs negative (referent category); distance was fitted as a categorical variable (1mm (referent) vs 2mm vs 5mm); and testing for trend across distance categories was as described for Model 1. For both adjusted models, we also examined pair-wise comparisons of the various distances used to declare a negative margin. Models were fitted using Proc NLmixed in SAS.

RESULTS

Thirty three23–55 studies reporting on 32,363 subjects were eligible for inclusion in this review, and provided margins data in 28,162 subjects (1506 LRs) included in our models. Study-specific characteristics are summarized in online-Appendix 2. Table 1 reports descriptive analyses; the median of the reported median follow-up times was 79.2 months (IQR 58.8–110.6), and the median prevalence of LR was 5.3% (IQR 2.3–7.6%) in 28,162 subjects with margins data. In 18 studies, all subjects had stage I-II BC, and 15 studies included subjects with stage I-II BC in >90% of the cohort – overall >96% of subjects in this meta-analysis had stage I-II invasive BC. Studies were retrospective, with the exception of Bellon et al36 (RCT of sequencing of therapy) and Voogd et al47 (which scored margins for BCS arms of two RCTs). The prevalence of LR in 3391 subjects with unknown margins (not included in models) was 10.0%.

Table 1.

Summary descriptive characteristics of studies in a meta-analysis of the effect of surgical margins on local recurrence in invasive breast cancer

| Variable | Number of studies providing data* | Median estimate | Inter-quartile range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study and cohort Characteristics | |||

| Recruitment time-frame (year): | |||

| Start | 33 | 1984 | 1979–1990 |

| End | 33 | 1996 | 1992–2001 |

| Mid-interval | 33 | 1990 | 1985–1995 (1980–2004) |

| Number of subjects in each study** | 33 | 701 | 452–1024 (range 79–3899) |

| Underlying prevalence of local recurrence | 33 | 5.3% | 2.3–7.6% |

| Median (or mean) follow-up time (months) | 33 | 79.2 | 58.8–110.6 (range 48.0–160) |

| Median time to local recurrence (months) | 14 | 53.5 | 47.0–60.0 |

| Proportion with systemic relapse/metastases as first (or first and only) event§ | 15 | 8.3% | 5.3–12.5% |

| Age, years: | |||

| Median (or mean) | 32 | 53.4 | 51.0–57.0 (range 45.0–60.6) |

| Minimum value in study-specific age range | 26 | 24.0 | 22.0–25.0 |

| Maximum value in study-specific age range | 26 | 86.0 | 79.0–89.0 |

| Tumour Characteristics | |||

| Stage distribution§§: | |||

| 0 | 11 | 0% | 0–1.4% |

| I | 11 | 55.0% | 52.5–56.9% |

| II | 11 | 44.4% | 39.4–45.9% |

| III | 11 | 0% | 0–0% (maximum 0.9%) |

| Node status: | |||

| Positive | 30 | 25.8% | 17.9–28.8% |

| Negative | 30 | 70.5% | 65.5–74.2% |

| Unknown or NR | 30 | 0.9% | 0–7.7% |

| Median tumour size (cm) | 8 | 1.6 | 1.5–2.1 |

| Tumour grade distribution: | |||

| Grade I | 15 | 25.0% | 16.7–32.1% |

| Grade II | 15 | 35.5% | 31.8–41.0% |

| Grade I–II combined | 17 | 66.0% | 57.5–68.9% |

| Grade III | 17 | 28.3% | 20.6–30.6% |

| Unknown or NR | 17 | 2.9% | 0.8–21.5% |

| Estrogen Receptor (ER) status: | |||

| Positive | 24 | 45.5% | 38.4–56.3% |

| Negative | 24 | 20.5% | 16.6–26.3% |

| Unknown or NR | 24 | 28.4% | 14.2–42.0% |

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) status: | |||

| Positive | 10 | 40.6% | 33.5–47.0% |

| Negative | 10 | 22.0% | 19.4–28.0% |

| Unknown or NR | 10 | 38.4% | 23.8–44.7% |

| Extensive intraductal component (EIC) (present) | 16 | 9.6% | 7.5–15.7% |

| Lympho-vascular invasion (LVI) (present) | 16 | 17.1% | 12.0–30.3% |

| Treatment Variables | |||

| Re-excision rate | 17 | 48.0% | 22.4–55.6% |

| Received chemotherapy† | 26 | 25.6% | 18.3–38.0% |

| Received endocrine therapy | 27 | 38.0% | 19.3–59.5% |

| Received any systemic therapy | 19 | 40.0% | 24.0–77.0% |

| Radiation therapy (doses in Gray, Gy) | |||

| Whole breast radiotherapy (WBR)††: | |||

| Median (or mean) WBR dose | 26 | 47.2 Gy | 45.0–50.0 Gy |

| Minimum dose in study-specific WBR range | 17 | 44.0 Gy | 40.0–46.0 Gy |

| Maximum dose in study-specific WBR range | 17 | 50.4 Gy | 50.0–54.0 Gy |

| Radiotherapy boost: | |||

| Received boost | 30 | 96.0% | 73.1–100% |

| Median boost dose | 12 | 10.0 Gy | 10.0–13.1 Gy |

| Minimum dose in study-specific boost range | 19 | 10.0 Gy | 9.0–14.8 Gy |

| Maximum dose in study-specific boost range | 19 | 18.0 Gy | 16.0–20.0 Gy |

| Total dose to tumour bed (TDT): | |||

| Median TDT | 13 | 61.0 Gy | 60.0–62.0 Gy |

| Received radiation to regional nodes± | 11 | 10.5% | 4.3–26.0% |

Variables reported in fewer than half of the included studies were not considered in our models.

Three studies reported data per affected/treated breast resulting in 42 additional breasts included as subjects in the total 32,363 subjects.

Reported in 17 studies, however we excluded 2 studies30,49 (reporting systemic relapse combined with other cancers and/or contralateral breast cancer) from descriptive analysis of this variable.

Type of chemotherapy varied across studies as well as within individual studies, or was not specified in some studies (details available from authors)

Stage distribution (where specified) – 18 studies included only subjects with stage I-II invasive breast cancer (only some of these studies reported exact distribution) and 15 studies included stage I-II in the vast majority of subjects (see Methods); overall >96% of subjects had stage I-II invasive breast cancer.

Whole breast radiotherapy (WBR) is an inclusion criterion in this review (all subjects had WBR).

Use of nodal irradiation was reported in 16 studies, however specific data were provided in 11 studies

For analytic purposes, one study using 1-high-power field47 for negative margins was included in the 1mm group, and one study using 3mm41 was included in the 5mm group. Neuschatz et al39 reported two thresholds for distance: 5mm was used in our analysis to balance the distribution of studies across distance categories.

Effect of Margins on LR

Model 1

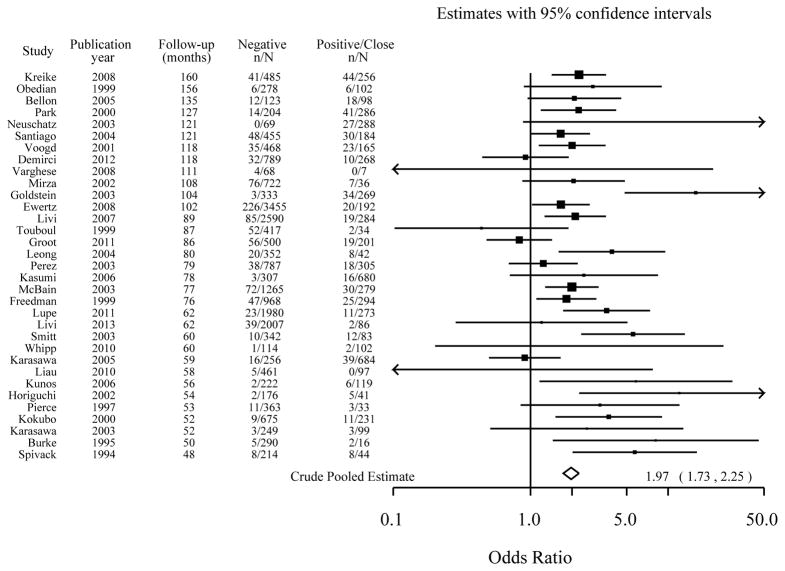

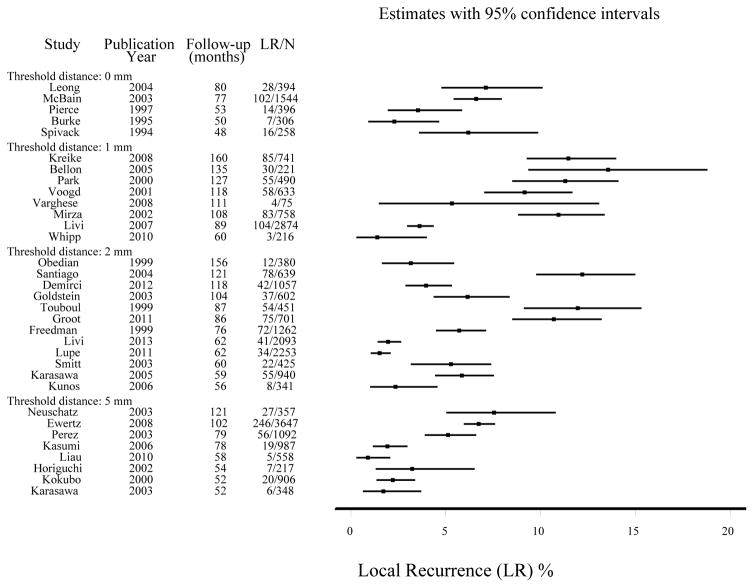

Based on 33 studies23–55 reporting LR in 1,506 of 28,162 subjects with data on positive and/or close and negative margins; study-specific and (unadjusted) pooled OR are shown in Figure 1. The proportion of subjects with LR stratified by the distance for negative margins is shown in Figure 2. Model estimates of effect are presented in Table 2 (model 1): in the unadjusted model (which does not factor differences in follow-up time between studies) the odds of LR were associated with margin status (P<0.001) and weakly associated with margin distance (P=0.060) with evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the distance for declaring negative margins increased (P=0.011 for trend). Based on prior information and evidence of association between the odds of LR and study-specific median follow-up time (P<0.0001) in this analysis, the adjusted model shows all estimates adjusted for median follow-up time (Table 2). In the adjusted model, the odds of LR were associated with margin status (P<0.001) but not with margin distance (P=0.12), and there was no statistical evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the distance for negative margins increased (P=0.21 for trend). There was no evidence of interaction: effect of margin status did not vary by distance or vice versa (P=0.17).

Figure 1.

The effect of margin status (positive/close relative to negative) on local recurrence: Study-specific odds ratios, ordered by median follow-up time.

Figure shows a crude pooled odds ratio of 1.97 (CI 1.73 – 2.25) [modeled pooled odds ratio, adjusted for negative distance was 1.98 (CI 1.73 – 2.25) and also adjusted for median follow-up time was 1.96 (CI 1.72 – 2.24)]. Data for Mirza45 and Ewertz30 are for loco-regional recurrence.

Figure 2.

Study-specific proportion with local recurrence (LR) stratified by threshold distance for negative margins, ordered by median follow-up time.

Data for Neuschatz39 were based on a 5mm distance; data for Perez41 were based on a 3mm distance (this was included in the 5mm group in our analysis); data for Mirza45 and Ewertz30 were for loco-regional recurrence.

Table 2.

Models of the effect of surgical margins on local recurrence (LR) in early-stage invasive breast cancer

| Number in model | Model estimates adjusted for study-specific median follow-up time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | LR | Odds of LR (Odds Ratio) | 95% CI | P-value§ [P for trend] | |

| Model 1 (median study-specific median follow-up time 6.6 years) | 28162 | 1506 | - | - | |

| Margin status | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 21984 | 1005 | 1.0 | - | |

| Positive/close | 6178 | 501 | 1.96 | 1.72 – 2.24 | |

| Threshold distance for negative margins† | 0.12 [0.21*] | ||||

| > 0mm | 2898 | 167 | 1.47 | 0.67 – 3.20 | |

| 1mm | 6008 | 422 | 1.0 | - | |

| 2mm | 11144 | 530 | 0.95 | 0.54– 1.67 | |

| 5mm | 8112 | 386 | 0.65 | 0.34 – 1.26 | |

| Model 2 (median study-specific median follow-up time 8.7 years) | 13081 | 753 | - | - | - |

| Margin status | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 9033 | 393 | 1.0 | - | |

| Close | 2407 | 176 | 1.74 | 1.42 – 2.15 | |

| Positive | 1641 | 184 | 2.44 | 1.97 – 3.03 | |

| Threshold distance for negative margins† | 0.90 [0.58] | ||||

| 1mm | 2376 | 235 | 1.0 | - | |

| 2mm | 8350 | 414 | 0.91 | 0.46 – 1.80 | |

| 5mm | 2355 | 103 | 0.77 | 0.32 – 1.87 | |

P reports P-value for association; P in square brackets gives P for trend and reflects whether there was statistical evidence of a decrease in the odds of LR as the threshold distance for declaring negative margins increased

Threshold distance for negative margins based on >0mm (5 studies), 1mm (referent; 8 studies), 2mm (12 studies), and 5mm (8 studies) in model 1; and based on 1mm (referent; 6 studies), 2mm (10 studies), and 5mm (3 studies) in model 2

Trend tested excluding studies using >0mm (test based on 28 studies) for model 1 – see Methods

Exclusion of two studies reporting data for loco-regional recurrence30,45 from the model had little effect on model estimates. The odds of LR were not associated with whether studies reported no losses or <5% losses27,31,36,38,41,48,54 to follow-up, or whether they did not provide any information on losses to follow-up (P=0.27; adjusted model). The odds of LR did not differ according to whether or not studies included some subjects treated with quadrantectomy (P=0.58; adjusted model).

Effect of study time-frame

Based on all 33 studies, the LR rates by median year of study recruitment declined over time (online-Figure 3); median year of study recruitment was strongly associated with LR rates (P <0.0001) in univariate analysis, and also associated with LR in the adjusted model (P =0.0086).

Effect of Covariates in model 1

Only covariates meeting pre-defined criteria for potential association or relevance (see Analysis) were further examined for effect on model estimates. Table 3 summarises results for these covariates, showing association with LR in univariate analysis, and the association once each of these covariates was entered into a model that included margins and median follow-up time; remaining associations were for age, median year of study recruitment, proportion receiving endocrine therapy, proportion ER positive, proportion that had re-excision, and LR type.

Table 3.

Model 1 – A model estimating the effect of surgical margins on local recurrence (LR) in invasive breast cancer adjusted for covariates (covariates examined in model 1 were selected using criteria described in Analysis)

| Covariate (Covariate definition and categories described in Methods) | P for association of covariate with LR | Margin status (adjusted OR) | Threshold distance for negative margins (adjusted OR) | P for association [P for trend] for margin distance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Unadjusted | Adjusted for margins & follow-up time | Negative | Positive/close | > 0 mm | 1mm | 2mm | 5mm | adjusted for covariate | |

| Effect of margins (adjusted for follow-up time) | 33 | 1.0 | 1.96** | 1.47 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.12 [0.21] | ||

| Age | 32 | 0.11 | 0.089 | 1.0 | 1.91** | 1.56 | 1.0 | 1.13 | 0.72 | 0.12 [0.29] |

| Median-year of study recruitment | 33 | <0.0001 | 0.0086 | 1.0 | 1.96** | 1.47 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.26 [0.14] |

| Proportion had endocrine therapy | 27 | <0.0001 | 0.0011 | 1.0 | 2.07** | 1.11 | 1.0 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.19 [0.32] |

| Proportion ER-positive | 24 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 1.0 | 2.26** | 0.87 | 1.0 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 0.44 [0.25] |

| Proportion had re-excision# | 17 | 0.032 | 0.088 | 1.0 | 2.06** | 1.41 | 1.0 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.22 [0.13] |

| LR type (first vs any)§ | 33 | 0.12 | 0.058 | 1.0 | 1.96** | 1.11 | 1.0 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.063 [0.074] |

Indicates OR significantly different to referent at P<0.001

Odds of LR increased as proportion receiving re-excision increased

LT type (see ‘Definition of variables’ in Methods): odds of LR were lower for ‘first’ than ‘any’

Adjusting model 1 for covariates (Table 3) did not alter the effect of margin status: there was a significant association (P<0.001) between margin status and the odds of LR in all adjusted analyses. In all (but one) of the adjusted models, there was no evidence of an association between the odds of LR and margin distance, nor evidence of a significant decrease in the odds of LR as the distance for negative margins increased (Table 3). In the model that adjusted for LR type, there was weak evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the threshold distance for negative margins increased (P=0.074 for trend).

Pair-wise comparisons for negative distance– adjusted model 1

The odds of LR were significantly higher for the studies using >0mm relative to 5mm (P=0.021): this finding persisted when adjusted for the covariates age (P=0.023), median-year of study recruitment (P=0.012), proportion with re-excision (P=0.048), or LR type (P=0.020). For all other pair-wise comparisons of negative distance, there were no statistically significant differences in the odds of LR in the adjusted model.

Model 2

Based on the subset of 19 studies24,25,28,29,31,33,35–37,39–42,47–52 reporting LR in 753 of 13,081 subjects with data on positive, close, and negative margins (from 14,952 subjects), estimates of effect are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted model, the odds of LR were significantly associated with margin status (P<0.001) but not with negative distance (P= 0.32); however there was weak evidence that LR odds decreased as the distance for negative margins increased (P=0.074 for trend). In the adjusted model 2 the odds of LR were associated with margin status (P<0.001) but not with margin distance (P=0.90) and there was no statistical evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the distance for declaring negative margins increased (P=0.58 for trend). There was no evidence of interaction between margin status and distance (P=0.53).

Effect of Covariates in model 2

Table 4 shows the covariates associated with LR (P <0.1) in a univariate analysis, and associations after entering each covariate into a model that also included margins and follow-up time. Adjusting model 2 for each covariate did not alter the effect of margin status: there was significant association (P<0.001) between margin status and the odds of LR in all adjusted models (Table 4). In all adjusted models, there was no evidence of association between margin distance and the odds of LR (P-value range 0.32 to 0.95) nor evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the threshold distance for negative margins increased (P for trend range 0.14 to 0.75).

Table 4.

Model 2 – A model estimating the effect of surgical margins on local recurrence (LR) in invasive breast cancer adjusted for covariates (covariates examined in model 2 were selected using criteria described in Analysis)

| Covariate (Covariate definition and categories described in Methods) | P for association of covariate with LR | Margin status (Adjusted OR) | Threshold distance for negative margins (Adjusted OR) | P for association [P for trend] for margin distance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Unadjusted | Adjusted for margins & follow-up time | Negative | Close | Positive | 1mm | 2mm | 5mm | adjusted for covariate | |

| Effect of margins (adjusted for follow-up time) | 19 | - | - | 1.0 | 1.74** | 2.44** | 1.0 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.53 [0.58] |

| Age | 18 | 0.089 | 0.11 | 1.0 | 1.68** | 2.35** | 1.0 | 1.12 | 0.94 | 0.86 [0.58] |

| Median-year of study recruitment | 19 | 0.0013 | 0.0055 | 1.0 | 1.76** | 2.45** | 1.0 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.32 [0.14] |

| Proportion had endocrine therapy | 16 | 0.0003 | 0.012 | 1.0 | 1.77** | 2.53** | 1.0 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.95 [0.75] |

| Proportion had radiation boost | 18 | 0.015 | 0.34 | 1.0 | 1.75** | 2.45** | 1.0 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.86 [0.75] |

| Proportion ER-positive | 15 | 0.036 | 0.078 | 1.0 | 1.92** | 2.66** | 1.0 | 1.08 | 0.63 | 0.67 [0.34] |

| Proportion had re-excision# | 11 | 0.0017 | 0.0029 | 1.0 | 1.97** | 2.84** | 1.0 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.64 [0.34] |

| LR type (first vs any) | 19 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 1.0 | 1.74** | 2.44** | 1.0 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.67 [0.34] |

Indicates OR significantly different to referent at P<0.001

Odds of LR increased as proportion receiving re-excision increased

Pair-wise comparisons for negative distance– adjusted model 2

For all pair-wise comparisons of negative distance (1mm vs 2mm, 1mm vs 5mm, or 2mm vs 5mm) there were no significant differences in the odds of LR in the adjusted model.

There was no evidence of an association between the stage-group categories (defined in Methods, ‘covariates’) and LR in the margins-adjusted models (P=0.25, P=0.65 for models 1 and 2 respectively).

DISCUSSION

It is remarkable that, more than 25 years after the demonstration that survival after BCS and whole breast irradiation is equivalent to survival after mastectomy1,2, there is still no consensus on what constitutes an adequate negative margin for BCT. Ink on tumor cells, a universally accepted definition of a positive margin, is associated with an increased risk of LR, but the amount of normal breast tissue which constitutes the optimal negative margin remains controversial. We have therefore systematically examined the evidence on the association of surgical margins with LR in early-stage invasive BC, providing estimates of effect that factor both margin status and the threshold distance for declaring negative margins across studies. We confirm that positive and close margins (combined) significantly increase the odds of LR (OR 1.96; P<0.001) relative to negative margins. However, the distance used to declare negative margins across studies was either weakly associated or not associated with the odds of LR in our two models respectively, and once adjusted for study-specific median follow-up time there was no statistical evidence that the distance used to define a negative margin significantly contributed to the risk of LR (P=0.12 and P=0.90 in models 1 and 2). In addition, in the adjusted models, there was no evidence that the odds of LR significantly decreased as the distance for defining negative margins increased (P=0.21 and P=0.58 for trend in models 1 and 2 respectively).

A survey of surgeons selected from a population-based sample, who were asked what negative margin width precluded the need for re-excision, and offered the choices of tumour not touching ink, >1–2mm, >5mm, and >10 mm, found that no choice was endorsed by more than 50% of the respondents, and only 11% selected tumour not touching ink.90 Similar findings were reported by Taghian et al15 in a survey of 1,133 radiation oncologists in North America and Europe. Again, no margin width was endorsed by more than 50% with European radiation oncologists tending to favor larger margins than their North American counterparts. The net result of this confusion is wide variation in the use of re-excision with reported rates ranging from 6% to 49% of cases91,92, with the majority noting re-excision in 15% to 30% of patients.18,20,93 McCahill et al18 reported that of 2200 BCS patients, 509 had re-excision, and 48% of these re-excisions were performed in patients with negative margins to obtain a more widely clear margin. Thus, failure to achieve consensus on margin width is a potential cause of unnecessary surgery, leading to worse cosmetic outcome, and increased health care costs. The findings of our analysis should therefore guide evidence-based practice through highlighting that more widely clear margins are unlikely to confer patient benefit.

Examination of covariates in our meta-analysis showed that the association between margin status and the odds of LR was significant in all adjusted models. The microscopic status of surgical margins, though not an exact test since it relies on sampling of representative tissue sections, is a robust prognostic factor for LR. In contrast, the distance used to define negative margins was not significantly associated with LR even after adjustment for potential confounders. We found little to no evidence of association between margin distance and the odds of LR, and there was little to no evidence that the odds of LR decreased as the distance for declaring negative margins across studies increased (Tables 3–4). It may be noted that the OR for the studies with the widest threshold distance (5mm) to define negative margins have relatively lower point estimates than the other categories, however, aside from the lack of statistical association, the estimates should be interpreted with consideration of the effect of adjustment for important covariates. For example, in Table 4, it is clear that adjustment for receipt of endocrine therapy or a radiation boost almost nullify differences in the estimated ORs for wide (5mm) relative to narrow (1mm) negative margins.

Pair-wise comparison between distance categories for negative margins (in the adjusted models) showed that there were no significant differences in the odds of LR, except that the odds of LR were higher for studies using >0mm relative to 5mm (P=0.021) in the adjusted model 1. For all other pair-wise comparisons of negative distance there were no statistically significant differences in the odds of LR in either of the adjusted models. The number of studies reporting negative margins as >0mm was small, and given the lack of significant differences among the other pair-wise comparisons of margin distance and the lack of overall significance of increasing margin width in decreasing LR in the models, this is unlikely to be clinically significant.

Relative to our previous meta-analysis on margins in BCT10, the updated OR estimates for the effect of margin status have remained largely unchanged, except for improved precision from the larger dataset in the present analysis. We previously reported weak evidence of a trend showing that the odds of LR decreased as the threshold distance for declaring negative margins increased, however this trend was not significant after adjustment for covariates.10 In the present meta-analysis that included several relatively more recent publications, there was even less evidence of an effect of negative distance (relative to our prior analysis), and after adjustment for study-specific median follow-up time there was no evidence that the distance used to define negative margins significantly contributed to the odds of LR. Overall, data synthesis in 28,162 subjects indicates that the risk of LR is not driven by the distance defining negative margins.

It is noteworthy that the overall median prevalence of LR in our analysis was only 5.3%, in spite of the fact that many of the included studies antedated the routine use of systemic therapy for small, node negative BCs. The observed temporal decline in LR can likely be attributed to the increasing use of systemic therapy, particularly in studies post-1990. Our work does not capture the full effect of improvements in systemic therapy, such as the use of aromatase inhibitors or HER2-directed therapy such as trastuzumab, on local control since the cohorts in this meta-analysis generally predated the routine use of these agents as adjuvant therapy (and given that our analysis required a minimum study median follow-up of 4 years to ensure a sufficient number of events). However, it is increasingly evident that therapies which improve distant disease-free survival result in a parallel decrease in LR94, a concept most clearly illustrated by the decrease in LR observed in patients with HER2-overexpressing cancers with the use of adjuvant trastuzumab.95,96 The failure of more widely clear margins to significantly decrease LR in the setting of relatively less use or less effective adjuvant therapy than is in use today makes it exceedingly unlikely that the inclusion of even more recently treated cohorts of BC patients would change our results, but if it did this would be expected to lead to even less effect from wider margins. Although the underlying (crude) LR rates for studies included in this review have indeed declined with time, adjusting for this covariate did not alter the estimated ORs for margin status which remained strongly associated with odds of LR. Therefore we conclude that the prognostic value of the status of surgical margins (positive vs negative) in BCT is not diminished by temporal declines in LR rates, and obtaining negative margins remains relevant to current oncologic practice.

This work focuses on the relative effect of surgical margins; the absence of a significant effect in our models for some variables may be due (at least in part) to the use of study-level information, or the infrequent reporting of data for some variables such as LVI or EIC. These limitations are inherent in study-level meta-analysis, and could be overcome by using individual patient data. Furthermore, the relatively homogeneous distribution of some covariates across studies (such as median age, aggregate dose of WBR) also accounts for a lack of association (or of strong association) for some factors. This does not mean that these factors are unrelated to LR risk – it means that these variables (at an aggregate level) were similar across studies and did not account for differences in the odds of LR in modeling the effect of margins. Additionally, it is increasingly clear that the risk of LR varies with the molecular subtype of BC as approximated by ER, PR, and HER2 status.97,98 We were unable to evaluate the interaction between BC subtype and margin width due to the lack of information on subtype or on HER2 status in a majority of studies. However, the finding that differences in rates of LR by subtype are similar after both BCT and mastectomy99 suggests that larger surgical excisions, whether in the form of more widely clear margins or mastectomy, are unlikely to alter aggressive biology. Negative surgical margins do not guarantee the absence of residual cancer within the breast; histological studies using serial sub-gross sectioning of the breast have shown that additional cancer can be found in the breast in a substantial proportion of women despite adequate surgical resection.100,101 A negative margin predicts that residual tumour burden is minimal and is likely to be controlled with adjuvant therapies.

This meta-analysis has investigated the association between surgical margins and LR, including the various distances used to define negative margins across a large number of studies. The implications for practice are that the association between margins and the risk of LR is largely driven by margin status, and ensuring negative margins in BCT contributes to reducing the risk of LR, however the threshold distance for defining negative margins does not significantly contribute to the odds of LR. The adoption of wider margins for declaring negative margins in BCT is unlikely to have a substantial additional benefit for long-term local control over a minimally-defined negative margin width in patients undergoing BCT for invasive BC.

Supplementary Material

Literature search and study selection strategy (flow-diagram adapted from PRISMA* recommendations102)

Summary of studies providing data on local recurrence in relation to quantified categories for surgical margins: Study-specific characteristics, margins definition, and treatment

Scatter plot of local recurrence rates by median year of study recruitment.

Synopsis.

Meta-analysis of the evidence on tumor margins in breast-conserving surgery for invasive breast cancer indicates that negative margins reduce the odds of local recurrence however the distance for defining negative margins is not significantly associated with reduced odds of local recurrence.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly funded by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) program grant 633003 to the Screening & Test Evaluation Program. Assoc/Prof Houssami receives research support through a National Breast Cancer Foundation (NBCF Australia) Practitioner Fellowship.

References

- 1.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Dongen JA, Voogd AC, Fentiman IS, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing breast-conserving therapy with mastectomy: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 10801 trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1143–1150. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poggi MM, Danforth DN, Sciuto LC, et al. Eighteen-year results in the treatment of early breast carcinoma with mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy: the National Cancer Institute Randomized Trial. Cancer. 2003;98:697–702. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blichert-Toft M, Rose C, Andersen JA, et al. Danish randomized trial comparing breast conservation therapy with mastectomy: six years of life-table analysis. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1992;(11):19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087–2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman LA, Kuerer HM. Advances in breast conservation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1685–1697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow M, Strom EA, Bassett LW, et al. Standard for breast conservation therapy in the management of invasive breast carcinoma. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2002;52:277–300. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.5.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singletary SE. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. American Journal of Surgery. 2002;184:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of surgical margins on local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46:3219–3232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, et al. Breast cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2009;7:122–192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz GF, Veronesi U, Clough KB, et al. Consensus conference on breast conservation. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2006;203:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singletary SE. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg. 2002;184:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow M. Margins in breast-conserving therapy: have we lost sight of the big picture? Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2008;8:1193–1196. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.8.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taghian A, Mohiuddin M, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, Ceilley E, Powell S. Current perceptions regarding surgical margin status after breast-conserving therapy: Results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2005;241:629–639. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157272.04803.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luini A, Rososchansky J, Gatti G, et al. The surgical margin status after breast-conserving surgery: discussion of an open issue. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment. 2009;113:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9929-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald S, Taghian AG. Prognostic factors for local control after breast conservation: does margin status still matter? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4929–4930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCahill LE, Single RM, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Variability in reexcision following breast conservation surgery. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:467–475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakamoto G, Inaji H, Akiyama F, et al. General rules for clinical and pathological recording of breast cancer 2005. Breast Cancer. 2005;12:Suppl-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, et al. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:1551–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in context. 2. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 228–247. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randolph A, Bucher H, Richardson WS, et al. Prognosis. In: Guyatt G, Rennie D, editors. Users’ guide to the medical literature. A manual for evidence-based clinical practice. Chicago: AMA Press; 2002. pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livi L, Meattini I, Franceschini D, et al. Radiotherapy boost dose-escalation for invasive breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery: 2093 patients treated with a prospective margin-directed policy. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demirci S, Broadwater G, Marks LB, Clough R, Prosnitz LR. Breast conservation therapy: the influence of molecular subtype and margins. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2012;83:814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupe K, Truong PT, Alexander C, Lesperance M, Speers C, Tyldesley S. Subsets of women with close or positive margins after breast-conserving surgery with high local recurrence risk despite breast plus boost radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2011;81:e561–e568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groot G, Rees H, Pahwa P, Kanagaratnam S, Kinloch M. Predicting local recurrence following breast-conserving therapy for early stage breast cancer: the significance of a narrow (<= 2 mm) surgical resection margin. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;103:212–216. doi: 10.1002/jso.21826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liau SS, Cariati M, Noble D, Wilson C, Wishart GC. Audit of local recurrence following breast conservation surgery with 5-mm target margin and hypofractionated 40-Gray breast radiotherapy for invasive breast cancer. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2010;92:562–568. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12699663903476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whipp E, Beresford M, Sawyer E, Halliwell M. True local recurrence rate in the conserved breast after magnetic resonance imaging-targeted radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2010;76:984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreike B, Hart AAM, van de Velde T, et al. Continuing Risk of Ipsilateral Breast Relapse After Breast-Conserving Therapy at Long-Term Follow-up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewertz M, Moe Kempel M, During M, et al. Breast conserving treatment in Denmark, 1989–1998. A nationwide population-based study of the Danish Breast Cancer Co-operative Group. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:682–690. doi: 10.1080/02841860802032769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varghese P, Gattuso JM, Mostafa AIH, et al. The role of radiotherapy in treating small early invasive breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livi L, Paiar F, Saieva C, et al. Survival and breast relapse in 3834 patients with T1-T2 breast cancer after conserving surgery and adjuvant treatment. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2007;82:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunos C, Latson L, Overmoyer B, et al. Breast conservation surgery achieving>or=2 mm tumor-free margins results in decreased local-regional recurrence rates. Breast Journal. 2006;12:28–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasumi F, Takahashi K, Nishimura S, et al. CIH-Tokyo experience with breast-conserving surgery without radiotherapy: 6.5 year follow-up results of 1462 patients. Breast Journal. 2006;12:Suppl-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karasawa K, Mitsumori M, Yamauchi C, et al. Treatment outcome of breast-conserving therapy in patients with positive or close resection margins: Japanese multi institute survey for radiation dose effect. Breast Cancer. 2005;12:91–98. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.12.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellon JR, Come SE, Gelman RS, et al. Sequencing of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in early-stage breast cancer: Updated results of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1934–1940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santiago RJ, Wu L, Harris E, et al. Fifteen-year results of breast-conserving surgery and definitive irradiation for Stage I and II breast carcinoma: The University of Pennsylvania experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leong C, Boyages J, Jayasinghe UW, et al. Effect of margins on ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after breast conservation therapy for lymph node-negative breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1823–1832. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuschatz AC, DiPetrillo T, Safaii H, Price LL, Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Wazer DE. Long-term follow-up of a prospective policy of margin-directed radiation dose escalation in breast-conserving therapy. Cancer. 2003;97:30–39. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein NS, Kestin L, Vicini F. Factors associated with ipsilateral breast failure and distant metastases in patients with invasive breast carcinoma treated with breast-conserving therapy: A clinicopathologic study of 607 neoplasms from 583 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:500–527. doi: 10.1309/8941-VDAJ-MKY2-GCLX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez CA. Conservation therapy in T1-T2 breast cancer: Past, current issues, and future challenges and opportunities. Cancer J. 2003;9:442–453. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smitt MC, Nowels K, Carlson RW, Jeffrey SS. Predictors of reexcision findings and recurrence after breast conservation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:979–985. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karasawa K, Obara T, Shimizu T, et al. Outcome of breast-conserving therapy in the Tokyo Women’s Medical University Breast Cancer Society experience. Breast Cancer. 2003;10:241–248. doi: 10.1007/BF02967655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McBain CA, Young EA, Swindell R, Magee B, Stewart AL. Local recurrence of breast cancer following surgery and radiotherapy: incidence and outcome. Clinical Oncology (Royal College of Radiologists) 2003;15:25–31. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mirza NQ, Vlastos G, Meric F, et al. Predictors of locoregional recurrence among patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:256–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02573063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horiguchi J, Koibuchi Y, Takei H, et al. Breast-conserving surgery following radiation therapy of 50 Gy in stages I and II carcinoma of the breast: the experience at one institute in Japan. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:1053–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voogd AC, Nielsen M, Peterse JL, et al. Differences in risk factors for local and distant recurrence after breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy for stage I and II breast cancer: Pooled results of two large European randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1688–1697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kokubo M, Mitsumori M, Ishikura S, et al. Results of breast-conserving therapy for early stage breast cancer: Kyoto university experiences. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials. 2000;23:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200010000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park CC, Mitsumori M, Nixon A, et al. Outcome at 8 years after breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy for invasive breast cancer: Influence of margin status and systemic therapy on local recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1668–1675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Touboul E, Buffat L, Belkacemi Y, et al. Local recurrences and distant metastases after breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy for early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freedman G, Fowble B, Hanlon A, et al. Patients with early stage invasive cancer with close or positive margins treated with conservative surgery and radiation have an increased risk of breast recurrence that is delayed by adjuvant systemic therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obedian E, Haffty B. Negative margin status improves local control in conservatively managed breast cancer patients. Cancer Journal from Scientific American. 1999;6:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierce LJ, Strawderman MH, Douglas KR, Lichter AS. Conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early-stage breast cancer using a lung density correction: the University of Michigan experience. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1997;39:921–928. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burke MF, Allison R, Tripcony L. Conservative therapy of breast cancer in Queensland. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1995;31:295–303. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)E0210-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spivack B, Khanna MM, Tafra L, Juillard G, Giuliano AE. Margin status and local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery. Archives of Surgery. 1994;129:952–956. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420330066013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freedman GM, Hanlon AL, Fowble BL, Anderson PR, Nicolaou N. Recursive partitioning identifies patients at high and low risk for ipsilateral tumor recurrence after breast-conserving surgery and radiation. [erratum appears in J Clin Oncol 2002 Dec 15;20(24):4727 Note: Nicoloau N [corrected to Nicolaou N]] J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4015–4021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schnitt SJ, Abner A, Gelman R, et al. The relationship between microscopic margins of resection and the risk of local recurrence in patients with breast cancer treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1994;74:1746–1751. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940915)74:6<1746::aid-cncr2820740617>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gage I, Schnitt SJ, Nixon AJ, et al. Pathologic margin involvement and the risk of recurrence in patients treated with breast-conserving therapy. Cancer. 1996;78:1921–1928. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961101)78:9<1921::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Buchholz TA, et al. Improving local control with breast-conserving therapy: A 27-year single-institution experience. Cancer. 2005;104:20–29. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horiguchi J, Iino Y, Takei H, et al. Surgical margin and breast recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. Oncology Reports. 1999;6:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wazer DE, Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Ruthazer R, et al. Factors determining outcome for breast-conserving irradiation with margin-directed dose escalation to the tumor bed. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:851–858. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00861-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smitt MC, Nowels KW, Zdeblick MJ, et al. The importance of the lumpectomy surgical margin status in long-term results of breast conservation. Cancer. 1995;76:259–267. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<259::aid-cncr2820760216>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solin LJ, Fowble BL, Schultz DJ, Goodman RL. The significance of the pathology margins of the tumor excision on the outcome of patients treated with definitive irradiation for early stage breast cancer [see comment] International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1991;21:279–287. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90772-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson ME, Schultz DJ, Reynolds C, Solin LJ. Outcomes in breast cancer patients relative to margin status after treatment with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy: The University of Pennsylvania experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Recht A, Come SE, Henderson IC, et al. The sequencing of chemotherapy and radiation therapy after conservative surgery for early-stage breast cancer. NEW ENGL J MED. 1996;334:1356–1361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Borger J, Kemperman H, Hart A, Peterse H, van DJ, Bartelink H. Risk factors in breast-conservation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:653–660. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kini VR, White JR, Horwitz EM, Dmuchowski CF, Martinez AA, Vicini FA. Long term results with breast-conserving therapy for patients with early stage breast carcinoma in a community hospital setting. Cancer. 1998;82:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiBiase SJ, Komarnicky LT, Heron DE, Schwartz GF, Mansfield CM. Influence of radiation dose on positive surgical margins in women undergoing breast conservation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:680–686. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tartter PI, Kaplan J, Bleiweis I, et al. Lumpectomy margins, reexcision, and local recurrence of breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2000;179:81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Renton SC, Gazet JC, Ford HT, Corbishley C, Sutcliffe R. The importance of the resection margin in conservative surgery for breast cancer. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 1996;22:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(96)91253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Truong PT, Jones SO, Kader HA, et al. Patients with t1 to t2 breast cancer with one to three positive nodes have higher local and regional recurrence risks compared with node-negative patients after breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2009;73:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poortmans PM, Collette L, Horiot JC, et al. Impact of the boost dose of 10 Gy versus 26 Gy in patients with early stage breast cancer after a microscopically incomplete lumpectomy: 10-year results of the randomised EORTC boost trial. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2009;90:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pittinger TP, Maronian NC, Poulter CA, et al. Importance of margin status in outcome of breast-conserving surgery for carcinoma. Surgery. 1994;116:605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yau TK, Soong IS, Chan K, et al. Clinical Outcome of Breast Conservation Therapy for Breast Cancer in Hong Kong: Prognostic Impact of Ipsilateral Breast Tumor Recurrence and 2005 St. Gallen Risk Categories Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bollet MA, Sigal-Zafrani B, Mazeau V, et al. Age remains the first prognostic factor for loco-regional breast cancer recurrence in young (<40 years) women treated with breast conserving surgery first. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hardy K, Fradette K, Gheorghe R, Lucman L, Latosinsky S. The impact of margin status on local recurrence following breast conserving therapy for invasive carcinoma in Manitoba. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:399–402. doi: 10.1002/jso.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rauschecker HF, Sauerbrei W, Gatzemeier W, et al. Eight-year results of a prospective non-randomised study on therapy of small breast cancer. The German Breast Cancer Study Group (GBSG) European Journal of Cancer. 1998;34:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones HA, Antonini N, Hart AA, et al. Impact of pathological characteristics on local relapse after breast-conserving therapy: a subgroup analysis of the EORTC boost versus no boost trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4939–4947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yoshida T, Takei H, Kurosumi M, et al. Ipsilateral breast tumor relapse after breast conserving surgery in women with breast cancer. Breast. 2009;18:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vujovic O, Cherian A, Yu E, Dar AR, Stitt L, Perera F. The effect of timing of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in patients with positive or close resection margins, young age, and node-negative disease, with long term follow-up. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2006;66:687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodriguez PA, Samper Ots PM, Lopez Carrizosa MC, et al. Early-stage breast cancer conservative treatment: high-dose-rate brachytherapy boost in a single fraction of 700 cGy to the tumour bed. Clinical & Translational Oncology: Official Publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societes & of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. 2012;14:362–368. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0809-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jobsen JJ, van der Palen J, Ong F, Meerwaldt JH. Differences in outcome for positive margins in a large cohort of breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving therapy. Acta Oncologica. 2007;46:172–180. doi: 10.1080/02841860600891325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Galimberti V, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, et al. Influence of margin status on outcomes in lobular carcinoma: experience of the European Institute of Oncology. Annals of Surgery. 2011;253:580–584. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d9a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCahill LE, Single R, Ratliff J, Sheehey-Jones J, Gray A, James T. Local recurrence after partial mastectomy: relation to initial surgical margins. American Journal of Surgery. 2011;201:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schroeder TM, Liem B, Sampath S, Thompson WR, Longhurst J, Royce M. Early breast cancer with positive margins: excellent local control with an upfront brachytherapy boost. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment. 2012;134:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu J, Hao XS, Yu Y, et al. Long-term results of breast conservation in Chinese women with breast cancer. Breast Journal. 2009;15:296–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shimauchi A, Nemoto K, Ogawa Y, et al. Long-term outcome of breast-conserving therapy for breast cancer. Radiation Medicine. 2005;23:485–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohsumi S, Sakamoto G, Takashima S, et al. Long-term results of breast-conserving treatment for early-stage breast cancer in Japanese women from multicenter investigation. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;33:61–67. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vordermark D, Lackenbauer A, Wulf J, Guckenberger M, Flentje M. Local control in 118 consecutive high-risk breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving therapy. Oncology Reports. 2007;18:1335–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Azu M, Abrahamse P, Katz SJ, Jagsi R, Morrow M. What is an adequate margin for breast-conserving surgery? Surgeon attitudes and correlates Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:558–563. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0765-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marudanayagam R, Singhal R, Tanchel B, O’Connor B, Balasubramanian B, Paterson I. Effect of cavity shaving on reoperation rate following breast-conserving surgery. Breast J. 2008;14:570–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Waljee JF, Hu ES, Newman LA, Alderman AK. Predictors of re-excision among women undergoing breast-conserving surgery for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1297–1303. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9777-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huston TL, Pigalarga R, Osborne MP, Tousimis E. The influence of additional surgical margins on the total specimen volume excised and the reoperative rate after breast-conserving surgery. Am J Surg. 2006;192:509–512. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morrow M, Harris JR, Schnitt SJ. Surgical margins in lumpectomy for breast cancer - Bigger is not better. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:79–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1202521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kiess AP, McArthur HL, Mahoney K, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab reduces locoregional recurrence in women who receive breast-conservation therapy for lymph node-negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1982–1988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Voduc KD, Cheang MCU, Tyldesley S, Gelmon K, Nielsen TO, Kennecke H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1684–1691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arvold ND, Taghian AG, Niemierko A, et al. Age, breast cancer subtype approximation, and local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3885–3891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lowery AJ, Kell MR, Glynn RW, Kerin MJ, Sweeney KJ. Locoregional recurrence after breast cancer surgery: A systematic review by receptor phenotype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:831–841. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lagios MD. Multicentricity of breast carcinoma demonstrated by routine correlated serial subgross and radiographic examination. Cancer. 1977;40:1726–1734. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4<1726::aid-cncr2820400449>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Holland R, Veling SH, Mravunac M, Hendriks JH. Histologic multifocality of Tis, T1-2 breast carcinomas. Implications for clinical trials of breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 1985;56:979–990. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<979::aid-cncr2820560502>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. 2009 (online source) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Literature search and study selection strategy (flow-diagram adapted from PRISMA* recommendations102)

Summary of studies providing data on local recurrence in relation to quantified categories for surgical margins: Study-specific characteristics, margins definition, and treatment

Scatter plot of local recurrence rates by median year of study recruitment.