Abstract

Vitamin D (VD) is essential for the human body and involved in a wide variety of critical physiological processes including bone, muscle, and cardiovascular health, as well as innate immunity and antimicrobial responses. Here, we elucidated the significance of the VD system in cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, which is one of the most common opportunistic infections in immunocompromised or –suppressed patients. We found that expression of vitamin D receptor (VDR) was downregulated in CMV-infected cells within 12 hours [hrs] post infection [p.i.] to 12 % relative to VDR expression in mock-infected fibroblasts and did not recover during the CMV replication cycle of 96 hrs. None of the biologically active metabolites of VD, cholecalciferol, calcidiol, or calcitriol, inhibit CMV replication significantly in human fibroblasts. In a feedback loop, expression of CYP24A1 dropped to 3 % by 12 hrs p.i. and expression of CYP27B1 increased gradually during the replication cycle of CMV to 970 % probably as a consequence of VDR inhibition. VDR expression was not downregulated during influenza virus or adenovirus replication. The potent synthetic vitamin D analog EB-1089 was not able to inhibit CMV replication or antagonize its effect on VDR expression. Only CMV replication, and none of the other viral pathogens evaluated, inhibited the vitamin D system in vitro. In view of the pleiotropism of VDR, CMV-mediated downregulation may have far-reaching virological, immunological, and clinical implications and thus warrant further evaluations in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Human cytomegalovirus (CMV), Vitamin D receptor, Calcitriol, EB-1089, CYP24A1, CYP27B1

1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is one of the clinically most significant infectious complications of solid-organ transplantation (reviewed in [1]). CMV infection, defined as a significant rise in the titer of CMV-specific antibodies, occurs in 44 % to 85 % of kidney, heart, and liver transplant recipients – primarily in the first 3 months post transplantation, when immunosuppression is most intense. CMV disease manifests in transplant recipients primarily in the organ transplanted with the risk of consecutive dissemination and impairment of other organs such as the central-nervous system, eye, and urogenital- or gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, active CMV infection is a significant independent predictor of acute graft rejection and occurrence of opportunistic infections [1,2].

Graft dysfunction and rejection are associated with vitamin D (VD) deficiency. In patients with end-stage organ failure awaiting transplant, VD insufficiency and deficiency are extremely common. Insufficient levels of vitamin D metabolites (25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D3] and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D [1α,25(OH)2D3] have been reported for patients with terminal congestive heart failure [3], pulmonary disease [4], liver failure [5], and chronic kidney disease [6]. International agreement upon the cut-offs for vitamin D insufficiency is still pending, but optimal level of 25(OH)D3 have been widely accepted to range between 50 and 80 nM for musculoskeletal health [7]. Observations in animal studies suggest that administration of 1α,25(OH)2D3 (calcitriol), which is the active metabolite of VD, can prevent acute allograft rejection following liver [8], kidney [9], and heart [10] transplantation. These observations could be validated in kidney transplant recipients, where calcitriol supplementation was associated with fewer episodes of acute cellular rejection [11], reduced glucocorticoid requirements [12], and decreased expression of co-stimulatory and human leukocyte antigen – DR (HLA-DR) molecules that may mediate allograft rejection [13].

The VD system is vital for the human organism and is involved in a wide variety of critical physiological processes. Its major biological function is the regulation of plasma calcium and phosphate homeostasis and bone remodeling, mostly by controlling resorption and metabolism of dietary calcium. VD system regulates also a diversity of other biological processes and hence, VD deficiency may increase the risk for multiple cardiovascular, inflammatory, autoimmune and malignant diseases (reviewed in [14]).

Conversion of cholecalciferol, the biologically inactive precursor of vitamin D, to its biologically active metabolite 1α,25(OH)2D3 (calcitriol) requires two hydroxylation steps that are accomplished by the 25-hydroxylases (CYP27A1 and CYP2R1) and by the 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) [15]. After binding calcitriol, the vitamin D receptor (VDR) is imported into the nucleus and binds to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) on the promoter region of target genes as a heterodimer with the retinoid-X receptor [16,17]. Consecutively, VDR regulates transcription of 200 to 1250 genes in a cell- and tissue-dependent manner (reviewed in [18]). In parallel, calcitriol induces in a negative feedback loop its rapid degradation by upregulation of the 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) and suppression of CYP27B1 expression for a tight control of 1α,25(OH)2D3 levels [16]

Calcitriol is involved also in the regulation of the innate immunity. Calcitriol influences the priming of the immune system, migration of immune cells, induction of regulatory T-cells, and production of antibacterial peptides [19,20]. For example, activation of the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) upregulates transcription of VDR gene in human macrophages [21]. As a consequence, hundreds of genes are activated [18], including those coding for the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin [21,22].

Calcitriol may also have direct antimicrobial effects. It triggers autophagy in macrophages and thereby inhibits replication of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) [23,24]. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected children treated with cholecalciferol and antiviral drugs have an earlier sustained virological response than those receiving only antiviral drugs [25]. Low vitamin D levels are associated with treatment failure among HCV-infected patients receiving pegylated-interferon and ribavirin [26]. Moreover, vitamin D was also found to be protective against bacterial infections such as Chlamydia spp. and mycobacterial infections [27–29].

The aim of the present study was to assess a possible antiviral effect of vitamin D and its metabolites in CMV infection. Systematic screening of solid-organ transplant patients for vitamin D deficiency and, if necessary, supplementation would be a non-toxic and very likely highly efficient measure to reduce the risk of CMV disease significantly. Surprisingly, vitamin D was unable to inhibit CMV replication; in contrast, CMV, but not other human viruses evaluated, affected significantly the vitamin D system.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and viruses

For the propagation of CMV, human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF, kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Mertens, University Medical Center Ulm, Germany) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM GlutaMAX, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) and Antibiotic-Antimycotic mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). HFF were then trypsinized, seeded to approximately 80 % confluence and subsequently infected with CMV (laboratory strain AD169) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The viral suspension was replaced by culture medium after 90 minutes. Virus culture was harvested after a total cytopathic effect (CPE) was visible. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 3000 g for 20 minutes and the virus supernatant was stored in DMEM supplemented with 20 % FCS at -80 °C. MOI was measured with use of a plaque assay as described previously [30]. The human adenovirus type 2 (ATCC) was propagated in the human alveolar adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line A549 grown in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 5 % FCS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Upon observation of a CPE, the virus was harvested by performing three freezing and thawing cycles followed by centrifugation at 4000 g for 10 minutes. Aliquots of the supernatant were used for subsequent experiments. For the propagation of influenza virus, A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12; Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated FCS (Linaris, Dossenheim, Germany). African green monkey kidney Vero cells (ECACC, 88020401) were cultivated in OptiPRO medium (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The influenza A/PuertoRico/8/34 virus (H1N1) and influenza A/Aichi/2/68 virus (H3N2) were used in the present study. Influenza A virus propagation was done in Vero cells in the presence of 5 µg/ml trypsin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) after infection with a MOI of 0.1. Virus titer concentrations were assessed by plaque assays on Vero cells. All cell lines were grown in a humidified 5 % CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

For analysis of VDR and VD-associated genes, HFF cells were seeded to reach 80 % confluence at time of infection, mock- or CMV-infected (MOI=5) and harvested 1, 12, 24, 36, 72 and 96 hrs p.i. A549 cells were used at a cell density of 6 x 105 cells per well in 6-well plates, mock- or adenovirus-infected (MOI=10) and harvested 1, 12 and 24 hrs p.i. For influenza A viruses, 1 x 106 A549 cells per well were seeded on 6-well plates, infected with the two different virus strains (MOI=5) or mock-infected and harvested 1, 12, 24, 36 and 48 hrs p.i.

For western blot analysis, HFF were seeded to reach 80 % confluence and infected with CMV AD169 with a MOI of 3. Final concentrations of calcitriol and EB-1089 were maintained constant during all phases of the experiment. Cells were harvested at time points p.i. indicated for each experiment, respectively and lysed by resuspension in lysis buffer (TBS, 1 % NP-40) and sonication.

2.2. CMV plaque assay

CMV plaque assays were performed as described previously [30]. Cholecalciferol (C9756, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), calcidiol, calcitriol (cat. no. H4014 & D1530, respectively, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and Ganciclovir (cat. no. 345700, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were used at two-fold dilutions starting with a concentration of 100 µM, respectively. For the evaluation of the vitamin D agonist EB-1089 (Seocalcitol EB-1089, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) two-fold dilutions starting with a concentration of 200 nM were used and supplemented with calcitriol at a constant concentration of 1 nM; Ganciclovir was used as control starting with 200 µm. The cutoff of the antiviral effectivity of the compounds was defined by the widely used IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration).

2.3. SDS-PAGE, Western blotting and antibodies

Protein concentration of lysates was measured with use of a commercially available BCA-assay according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell lysates were diluted for western blot analysis in 5x reducing sample buffer (300 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 50 % glycerol, 0.05 % Bromophenol blue, 10 % SDS and 10 % 2-Mercaptoethanol) and boiled at 99°C for 5 minutes. Subsequently, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with use of 8 % gels. Membranes were blocked with StartingBlock T20 (PBS) Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and evaluated with use of the following primary antibodies: anti-VDR (SAB4503071, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), anti-IE1/pp72 (sc-69834, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA), and anti-beta-tubulin HRP (#ab21058, abcam, Cambridge, UK). Secondary HRP-labeled antibodies to target anti-VDR and anti-IE1 primary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immuno Research (West Grove, PA, USA). SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to visualize the blots. Membranes were stripped with Restore PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for reprobing. Band signal intensity on western blots was measured with use of a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Biorad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and analyzed using the Image Lab 5.0 software (Biorad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

2.4. Real-time PCR assays

RNA extraction was performed on a QIAcube fully automatic sample processor using the RNeasy Mini Kit with the "Customized protocol for purification of total RNA from animal cells (with QIAshredder)" (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). The elution volume was 50 µL. RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 3 µg RNA with the "High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor" (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a 60 µl reaction volume according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on the ABI Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in duplicates using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR cycling conditions were 10 minutes (min) at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds (s) at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C. Beta-2-microglobulin (hβ2M) was used as housekeeping gene. Primers for VDR, CYP24A1, CYP27B1 and hβ2M have been described previously [31–33]. The ΔΔCt method was applied to calculate fold changes in gene expression, relative to housekeeping genes and normalized to a commercially available total RNA calibrator (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to Livak et al [31].

3. Results

3.1. Expression of VDR mRNA is downregulated during CMV replication

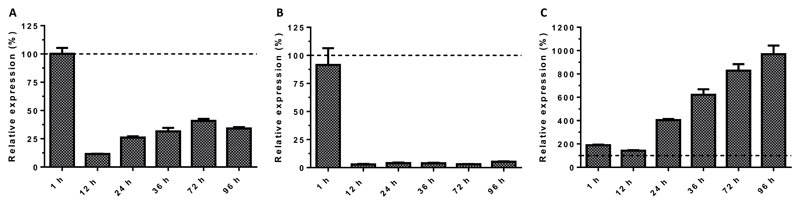

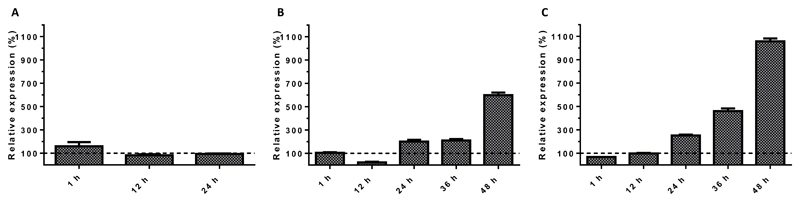

To evaluate the impact of CMV infection on the vitamin D system, we assessed the relative mRNA expression of VDR, the 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and the 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1). Quantification of VDR-specific mRNA in CMV-infected human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) revealed that VDR expression was downregulated to 12 % within 12 hours (hrs) post infection (p.i.) relative to the VDR expression in mock-infected HFF (Fig 1). After 12 hrs p.i., VDR expression recovered partially but maximum relative values did not exceed 41 % during the 96 hrs of observation, which is the equivalent time for one replication cycle of the CMV strain AD169 used. In parallel, relative gene expression of CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 were quantified to evaluate feedback loops associated with VDR expression. Relative expression of CYP24A1 dropped in CMV infected HFF to 3 % relative to mock-infected HFF 12 hrs p.i. and did not recover substantially during the observation period of 96 hrs p.i. In contrast, expression of CYP27B1 increased gradually during the replication cycle of CMV relative to that measured in mock-infected HFF from 190 % at 12 hrs p.i. to 970 % at 96 hrs p.i. (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Expression of VDR (A), CYP24A1 (B), and CYP27B1 (C) during CMV replication.

HFF were infected with CMV (strain AD169, MOI 5) and harvested at the indicated time points p.i. Expression of VDR, CYP24A1 and CYP27B1 in CMV infected HFF was analyzed by qRT-PCR relative to mock-infected cell samples harvested at the corresponding time p.i. Dashed lines indicate no change in gene expression of CMV-infected HFF relative to mock-infected HFF. Arrow bars show standard error of the mean (SEM).

3.2. Vitamin D metabolites do not inhibit CMV replication

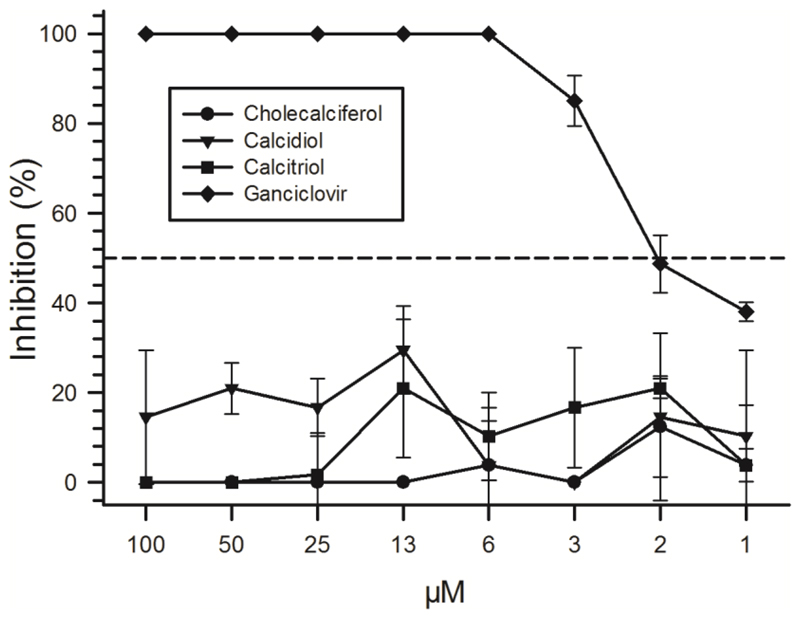

To investigate whether vitamin D or its metabolites inhibit the replication of CMV, we performed plaque reduction assays in HFF treated with decreasing concentrations of cholecalciferol, calcidiol, or calcitriol. In these experiments, neither the biologically most active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, nor its precursors cholecalciferol or calcidiol inhibited the replication of CMV significantly despite supra-physiological concentrations (Fig 2). We observed a minor inhibition of viral replication in the range of 0-30 %. However, this inhibition did not exceed the IC50 (half maximum inhibitory concentration). Of note, cholecalciferol at the maximum concentration of 100 µM induced a pronounced cytopathic effect (CPE) in the HFF cells and the antiviral effect at this high concentration was therefore not evaluated. A reduced viability of cells reduces the permissiveness for viral replication and would thereby bias results. The antiviral drug ganciclovir, used as control, had a strong antiviral effect causing 100 % inhibition of viral replication down to a final concentration of 6.25 µM.

Figure 2. Inhibition of CMV replication in vitro by vitamin D and its metabolites.

HFF were seeded to 100 % confluency, infected with CMV strain AD169, washed and incubated with two-fold dilutions of cholecalciferol, calcidiol, or calcitriol. As control, the antiviral compound Ganciclovir was used. All compounds were used in a two-fold dilution series with highest concentrations of 100 µM each. All experiments were done in triplicates (arrow bars show SEM). The dashed line indicates 50 % inhibition of CMV replication.

3.3. VDR protein levels correspond with VDR gene expression

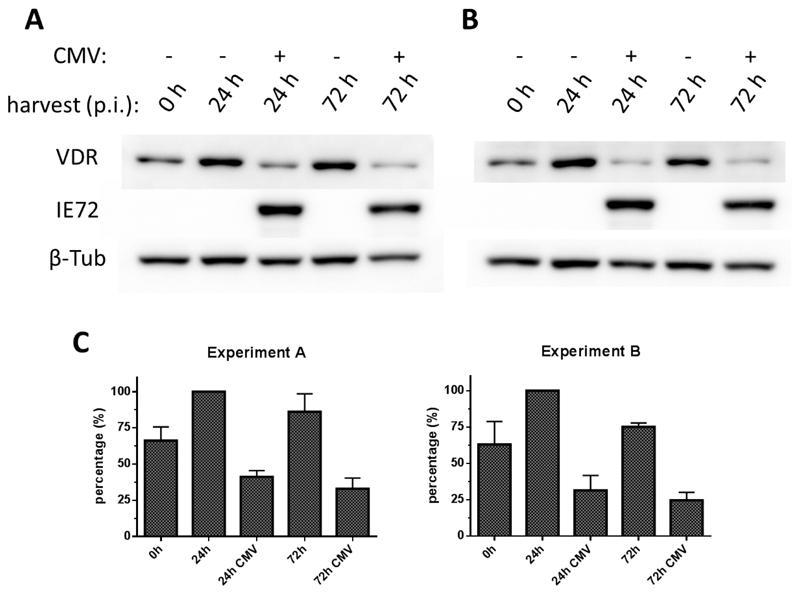

Expression of mRNA may not correlate with protein levels because of occasionally discordant regulation [34,35]. To examine VDR gene expression at the protein level, HFF were CMV- or mock-infected and VDR protein levels were evaluated by Western blotting. The VDR-specific signal measured in lysate from mock-infected, calcitriol-treated HFF was stronger 24 and 72 hrs p.i. than at 0 hrs p.i., which indicates calcitriol-mediated upregulation of VDR (Fig 3A). The VDR-specific signal measured in CMV-infected, calcitriol-treated HFF was clearly weaker than in the corresponding mock-infected samples collected at the same time points 24 and 72 hrs p.i. To confirm presence of viral infection in the HFF, all samples were also probed with a mAb specific for the immediate early antigen-1 (IE1/pp72) of CMV, which is detectable within one hour p.i.

Figure 3. Downregulation of VDR protein generation during early and late phases of CMV infection.

HFF were infected with CMV AD169 (MOI 3) or mock-infected and treated with (A) calcitriol at a final concentration of 1 nM or (B) calcitriol (1 nM) together with the VDR agonist EB-1089 at a final concentration of 100 nM. Cell lysates were probed with VDR-specific antibody to test for VDR protein expression (VDR), an anti-IE72 antibody to verify presence of virus in the infected samples (IE72) and an antibody specific for beta-tubulin to confirmed equal protein amounts loaded on the blotting membrane (β-Tub). C: From two experiments, each bands’ signal intensity was normalized to the signal intensity of the corresponding loading control (β-Tub). Percentage of each bands’ signal intensity considering the strongest band as 100 % was calculated and mean values and SEM (n=2) of the percentage evaluation are shown.

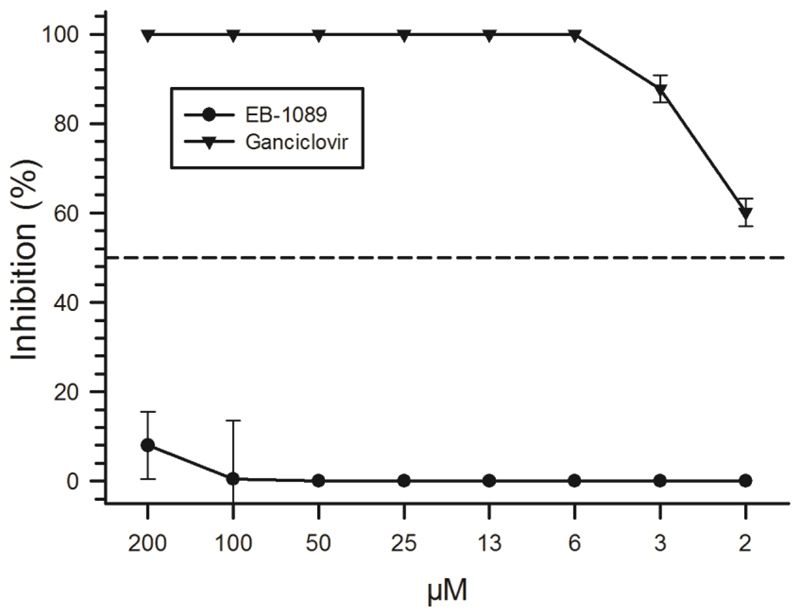

To evaluate whether the downregulation of VDR during CMV replication may be antagonized, CMV- or mock-infected HFF were treated in parallel with EB-1089, a vitamin D analog that has been used successfully to counteract the VDR gene downregulation induced by HIV replication [36,37] (Fig 3B). In these experiments, signals obtained when probing lysates from CMV- and mock-infected HFF were identical to those measured without EB-1089, which indicates that EB-1089 was not able to counteract VDR protein downregulation during CMV replication (Fig 3B). To evaluate a potential antiviral effect of EB-1089, plaque reduction assays were carried out in HFF treated with decreasing concentrations of the compound (Fig 4). In contrast to Ganciclovir, EB-1089 had only a marginal inhibitory effect (<10 %) on CMV replication compared with the mock-treated HFF - even at the highest concentrations used (200 nM).

Figure 4. Inhibition of CMV replication by the VDR agonist EB-1089.

100 % confluent HFF were seeded in 24-wells, infected with CMV strain AD169 and treated with 1 nM Calcitriol and two-fold dilution series of EB-1089 or Ganciclovir starting with 200 nM or 200 µM, respectively. All experiments were done in triplicates (arrow bars show SEM). The dashed line indicates 50 % inhibition of CMV replication.

3.4. VDR gene expression is not downregulated during influenza virus or adenovirus replication

To evaluate whether the observed down-regulation of the VDR gene during CMV replication is a common phenomenon occurring in association with viral infections, we evaluated VDR gene expression in mammalian cells infected with the influenza A/PuertoRico/8/34 virus (H1N1), influenza A/Aichi/2/68 virus (H3N2), or with one human adenovirus type 2 strain (HAdV2). Cells were harvested at 1, 12 and 24 hrs for adenovirus and 1, 12, 24, 36 and 48 hrs p.i. for influenza A viruses. These harvesting time points were chosen because of the shorter replication cycles of influenza A and adenoviruses in cell culture compared with CMV, and because the CPE occurring after 24 and 48 hrs; respectively. VDR mRNA expression of adenovirus-infected samples relative to mock-infected control peaked initially (one hour p.i.) at 160 % but decreased thereafter to 82 % and 95 % at 12 and 24 hrs p.i., respectively. Of note, this high relative expression is based on an outliner in the replicates with ~220 % in contrast to the corresponding replicate which showed almost perfectly 100 % (99.88 %). Relative VDR expression of influenza A virus infected samples increased with ongoing virus infection after an initial drop. Maximum levels were reached 96 hrs p.i. influenza A(H1N1) virus increased VDR mRNA levels by 600% while A(H3N2) by 1058 % relative to the mock-infected controls (Fig 5).

Figure 5. VDR gene expression in mammalian cells during influenza A virus or adenovirus type 2 (AdV2) infection.

A549 cells were infected with adenovirus type 2 (MOI=10) (A), influenza A/PuertoRico/8/34 virus (H1N1) (B) or influenza A/Aichi/2/68 virus (H3N2) (C) (MOI=5, respectively). Adenovirus and influenza A virus-infected cell cultures were harvested at the indicated time points p.i., respectively. Relative expression of VDR was analyzed by qRT-PCR with use of mock-infected cell samples harvested at the corresponding time p.i. Dashed lines indicate no change in gene expression of CMV-infected HFF relative to mock-infected HFF. Arrow bars show SEM.

4. Discussion

In the past few years, there has been increasing interest in the complex interplay between vitamin D and infectious pathogens (for a review see [38]). Vitamin D supplementation is beneficial for patients with HIV, hepatitis C virus, Chlamydia spp. or mycobacterial infection [23–29]. A significant reduction in the risk of CMV infection and disease by vitamin D supplementation would be highly attractive because of a high therapeutic index of vitamin D, the ease of application (oral solutions), and added benefits such as improved musculoskeletal health. Contrary to expectation, we found that CMV infection interferes with the vitamin D system of mammalian cells. CMV infection downregulated VDR expression and this downregulation was specific for CMV and was not observed for other, common human viruses. This observation may have far-reaching virological, immunological, and clinical implications.

CMV is one of the most significant viral pathogens in immunocompromised or – suppressed patients. In solid-organ and bone-marrow transplant patients, CMV is the most common opportunistic virus infection with an incidence of up to 85 % and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. HIV-infected patients are at high risk for CMV disease during periods of intense immunodeficiency [1]. Treatment of patients with the monoclonal antibody Alemtuzumab for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is accompanied with CMV reactivation and disease in up to 66 % of patients [39]. Moreover, CMV infection is the leading cause of congenital viral infection in Western countries with an overall birth prevalence of 0.64 % [40]. In view of the significant impact of CMV infection on human health, better prophylactic and therapeutic options are urgently needed. We found, however, in vitro evidence that CMV replication is not inhibited by calcitriol, the biologically active vitamin D metabolite, nor by cholecalciferol or calcidiol, even at supra-physiological concentrations. Evidence on the risk of CMV infection and disease in association with vitamin D deficiency is limited so far to the study of only one cohort of kidney transplant patients [41]. In concordance with our findings, vitamin D deficiency was not associated with CMV disease [41]. Hence, vitamin D supplementation may not affect significantly CMV replication in vivo.

We found, a rapid, pronounced, and sustained downregulation of the VDR gene during CMV replication. We validated the gene expression data also on protein level and demonstrated a significant decrease in VDR protein levels during CMV replication. VDR is ubiquitously expressed in the human body including cells of the pancreas, kidneys, intestine, bones and cartilage, epithelium, endocrine glands and testes, as well as in T-cells, monocytes and dendritic cells [42,43]. As VDR participates in multiple signaling pathways, low VDR levels would not only compromise vitamin D signaling but would also derail the homeostasis of other signaling pathways. In VDR knock-out mice the risk for severe musculo-skeletal disorders [44], dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome [45], defective autophagy [46], improper wound healing [47], or bacterial, or mycobacterial infections [29] is significantly increased. In kidney, or liver transplant patients, VDR polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of CMV disease [48,49]. The present observation that CMV replication downregulates VDR expression warrants further clinical trials to elucidate the complex interference of CMV with the vitamin D system in vivo.

Interference of CMV with vitamin D signalling may be very different compared with that of other intracellular pathogens. HIV for example, infects kidney cells, hijacks the cellular machinery to provide suitable host factors for viral replication, and thereby, downregulates VDR gene expression and triggers HIV-associated nephropathy [50]. The chemotherapeutic vitamin D analog EB-1089 inhibited this HIV-induced VDR gene downregulation in kidney cells [36]. In our study, EB-1089 did not affect VDR expression during CMV replication despite the use of comparably high concentrations [51]. EB-1089 had no significant effect on CMV replication either. HIV-caused VDR downregulation was reported to be mediated through generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [36]. In contrast to HIV, CMV induces expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes to combat ROS [52]. Hence, the mechanisms and functional consequences of VDR gene downregulation are very likely different between HIV and CMV infection explaining the differences in effectiveness of EB-1089 on replication of these two viruses.

The observed upregulation of CYP27B1 and downregulation of CYP24A1 during CMV replication may further indicate a specific viral interference with VDR gene expression. In the present study, CMV replication was associated with a marked and persistent suppression of CYP24A1 expression within 12 hrs p.i. and a gradual and marked upregulation of CYP27B1 expression. These observations may indicate not only a VDR gene downregulation during CMV replication but also an inhibition of the negative feedback loop by a relative deficiency of VDR-associated calcitriol. The relative deficiency in VDR-associated calcitriol could not be antagonized by supplementation of high concentrations of this vitamin D metabolite during CMV replication.

Regulation of VDR, CYP27B1, and CYP24A1 may vary depending on tissue or cell type and differentiation or activation status of the cells evaluated [53]. For example, VDR is expressed in activated but not in resting T-cells [42,43]. Interestingly, CMV infects several different mammalian cells – predominantly monocytes-macrophages, as well as endothelial and epithelial cells. Differentiation of monocytes into macrophages is required for achieving a fully permissive CMV infection [54]. Calcitriol enhances VDR expression of monocytes and macrophages [55]. Hence, the observed downregulation of VDR expression under CMV replication may be rather an ancillary effect of CMV during viral modulation of the cellular machinery to provide suitable host factors for viral replication.

In contrast to the observed downregulation of VDR gene expression during CMV or HIV infection, our observations indicate that downregulation of VDR gene expression is not universally associated with viral infections. To evaluate if other viral pathogens also interfere with the VDR-system, we performed the same gene expression screens on influenza virus or adenovirus-infected cells. VDR gene expression was even upregulated continuously during influenza virus infection. A potential explanation for these different VDR responses to the viral infections evaluated may be based on the innate immune response to intracellular pathogens. Activation of TLRs up-regulates expression of VDR and CYP27B1 followed by induction of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin [21,56,57]. Recently, Landais et al. demonstrated that the viral micro-RNA (miRNA) miR-UL112-3p inhibits TLR2 signaling and NFκB activation during CMV infection [58]. Moreover, innate immune responses to HIV infection follow different pathways than responses to CMV or influenza virus infection, which may also explain the differences in the observed response to calcitriol supplementation and EB-1089 treatment in vitro.

In conclusion, we found that vitamin D does not inhibit CMV replication significantly in vitro. Instead, CMV replication rapidly and efficiently downregulated VDR gene expression and modified the expression of the vitamin D system significantly. The interference with VDR expression was specific for CMV and not for other common, human viruses such as adenovirus or influenza viruses. Modifications of this system may have extensive consequences beyond the cellular level. Changes of the vitamin D homeostasis could significantly affect more than 80 pathways linked to cancer, autoimmune disorders, and cardiovascular disease [18,28,59]. Our observations in an in vitro model of CMV infection warrant further in vitro and in vivo evaluations for a comprehensive characterization of the consequences on a global scale.

Funding Information

This study was supported by a research grant from the Austrian Science Fund #P25353-B21 for CS; the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) Grant LS12-047 for EK; MS is a recipient of a DOC Fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

References

- [1].Steininger C. Clinical relevance of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with disorders of the immune system. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:953–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hartmann A, Sagedal S, Hjelmesaeth J. The natural course of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2006;82:S15–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000230460.42558.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shane E, Mancini D, Aaronson K, Silverberg SJ, Seibel MJ, Addesso V, McMahon DJ. Bone Mass, Vitamin D Deficiency, and Hyperparathyroidism in Congestive Heart Failure. Am J Med. 1997;103:197–207. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shane E, Silverberg SJ, Donovan D, Papadopoulos A, Staron RB, Addesso V, Jorgesen B, McGregor C, Schulman L. Osteoporosis in lung transplantation candidates with end-stage pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1996;101:262–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Monegal A, Navasa M, Guañabens N, Peris P, Pons F, Martínez de Osaba MJ, Rimola A, Rodés J, Muñoz-Gómez J. Bone mass and mineral metabolism in liver transplant patients treated with FK506 or cyclosporine A. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68:83–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02678145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stavroulopoulos A, Porter CJ, Roe SD, Hosking DJ, Cassidy MJD. Relationship between vitamin D status, parathyroid hormone levels and bone mineral density in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:63–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:713–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhang A, Zheng S, Jia C, Wang Y. Role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in preventing acute rejection of allograft following rat orthotopic liver transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117:408–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Becker BN, Hullett DA, O’Herrin JK, Malin G, Sollinger HW, DeLuca H. Vitamin D as immunomodulatory therapy for kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:1204–6. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000031949.70610.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hullett DA, Cantorna MT, Redaelli C, Humpal-Winter J, Hayes CE, Sollinger HW, Deluca HF. Prolongation of allograft survival by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Transplantation. 1998;66:824–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tanaci N, Karakose H, Guvener N, Tutuncu NB, Colak T, Haberal M. Influence of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 as an immunomodulator in renal transplant recipients: a retrospective cohort study. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2885–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Uyar M, Sezer S, Arat Z, Elsurer R, Ozdemir FN, Haberal M. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) therapy is protective for renal function and prevents hyperparathyroidism in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2069–73. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ahmadpoor P, Ilkhanizadeh B, Ghasemmahdi L, Makhdoomi K, Ghafari A. Effect of active vitamin D on expression of co-stimulatory molecules and HLA-DR in renal transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2009;7:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stein EM, Shane E. Vitamin D in organ transplantation. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2107–18. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1523-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gröschel C, Tennakoon S, Kállay E. Elsevier; 2015. Cytochrome P450 Function and Pharmacological Roles in Inflammation and Cancer. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pike JW, Meyer MB. The vitamin D receptor: new paradigms for the regulation of gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:255–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.007. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yasmin R, Williams RM, Xu M, Noy N. Nuclear import of the retinoid X receptor, the vitamin D receptor, and their mutual heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40152–40160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hossein-nezhad A, Spira A, Holick MF. Influence of vitamin D status and vitamin D3 supplementation on genome wide expression of white blood cells: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Verstuyf A, Carmeliet G, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: a pleiotropic hormone. Kidney Int. 2010;78:140–145. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bikle DD. Vitamin D and immune function: Understanding common pathways. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7:58–63. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Schauber J, Wu K, Meinken C, Kamen DL, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science (80-. ) 2006;311:1770–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schauber J, Dorschner Ra, Coda AB, Büchau AS, Liu PT, Kiken D, Helfrich YR, Kang S, Elalieh HZ, Steinmeyer A, Zügel U, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:803–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI30142DS1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Campbell GR, Spector Sa. Hormonally active vitamin D3 (1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) triggers autophagy in human macrophages that inhibits HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18890–18902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].vinh quoc Luong K, Thi Hoàng Nguyen L. The beneficial role of vitamin D in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eltayeb AA, Abdou MAA, Abdel-Aal AM, Othman MH. Vitamin D status and viral response to therapy in hepatitis C infected children. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1284–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gutierrez JA, Parikh N, Branch AD. Classical and emerging roles of vitamin D in hepatitis C virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:387–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bikle DD. Vitamin D and the immune system: role in protection against bacterial infection. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:348–52. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ff64a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wöbke TK, Sorg BL, Steinhilber D. Vitamin D in inflammatory diseases. Front Physiol. 2014;5:244. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].He Q, Ananaba GA, Patrickson J, Pitts S, Yi Y, Yan F, Eko FO, Lyn D, Black CM, Igietseme JU, Thierry-Palmer M. Chlamydial infection in vitamin D receptor knockout mice is more intense and prolonged than in wild-type mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;135:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Britt WJ. Human cytomegalovirus: propagation, quantification, and storage. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2010;Chapter 14 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc14e03s18. Unit 14E.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Horváth HC, Lakatos P, Kósa JP, Bácsi K, Borka K, Bises G, Nittke T, Hershberger PA, Speer G, Kállay E. The candidate oncogene CYP24A1: A potential biomarker for colorectal tumorigenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:277–85. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.954339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lucerna M, Pomyje J, Mechtcheriakova D, Kadl A, Gruber F, Bilban M, Sobanov Y, Schabbauer G, Breuss J, Wagner O, Bischoff M, et al. Sustained expression of early growth response protein-1 blocks angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6708–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maier T, Güell M, Serrano L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3966–3973. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wang D. Discrepancy between mRNA and protein abundance: Insight from information retrieval process in computers. Comput Biol Chem. 2008;32:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Salhan D, Husain M, Subrati A, Goyal R, Singh T, Rai P, Malhotra A, Singhal PC. HIV-induced kidney cell injury: role of ROS-induced downregulated vitamin D receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F503–14. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00170.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chandel N, Sharma B, Husain M, Salhan D, Singh T, Rai P, Mathieson PW, Saleem Ma, Malhotra A, Singhal PC. HIV compromises integrity of the podocyte actin cytoskeleton through downregulation of the vitamin D receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F1347–57. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00717.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kearns MD, Alvarez JA, Seidel N, Tangpricha V. Impact of vitamin D on infectious disease. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:245–62. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Laurenti L, Piccioni P, Cattani P, Cingolani A, Efremov D, Chiusolo P, Tarnani M, Fadda G, Sica S, Leone G. Cytomegalovirus reactivation during alemtuzumab therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: incidence and treatment with oral ganciclovir. Haematologica. 2004;89:1248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253–76. doi: 10.1002/rmv.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lee JR, Dadhania D, August P, Lee JB, Suthanthiran M, Muthukumar T. Circulating Levels of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Acute Cellular Rejection in Kidney Allograf Recipients. Transplantation. 2014;00:1–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang Y, Zhu J, DeLuca HF. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Brennan a, Katz DR, Nunn JD, Barker S, Hewison M, Fraher LJ, O’Riordan JL. Dendritic cells from human tissues express receptors for the immunoregulatory vitamin D3 metabolite, dihydroxycholecalciferol. Immunology. 1987;61:457–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Demay MB. Physiological insights from the vitamin D receptor knockout mouse. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9633-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jin D, Wu S, Zhang Y-G, Lu R, Xia Y, Dong H, Sun J. Lack of Vitamin D Receptor Causes Dysbiosis and Changes the Functions of the Murine Intestinal Microbiome. Clin Ther. 2015;37:996–1009.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wu S, Zhang Y-G, Lu R, Xia Y, Zhou D, Petrof EO, Claud EC, Chen D, Chang EB, Carmeliet G, Sun J. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor deletion leads to defective autophagy in colitis. Gut. 2015;64:1082–94. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Elizondo RA, Yin Z, Lu X, Watsky MA. Effect of vitamin D receptor knockout on cornea epithelium wound healing and tight junctions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:5245–51. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhao Y-G, Shi B-Y, Qian Y-Y, Bai H-W, Xiao L, He X-Y. Clinical significance of monitoring serum level of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in patients with acute kidney allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:319–22. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Falleti E, Bitetto D, Fabris C, Cmet S, Fornasiere E, Cussigh A, Fontanini E, Avellini C, Barbina G, Ceriani E, Pirisi M, et al. Association between vitamin D receptor genetic polymorphisms and acute cellular rejection in liver-transplanted patients. Transpl Int. 2012;25:314–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chandel N, Sharma B, Salhan D, Husain M, Malhotra a, Buch S, Singhal PC. Vitamin D receptor activation and downregulation of renin-angiotensin system attenuate morphine-induced T cell apoptosis. AJP Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C607–C615. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00076.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Høyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Mathiasen IS, Elling F, Jäättelä M. Vitamin D analog EB1089 triggers dramatic lysosomal changes and Beclin 1-mediated autophagic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1297–1309. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tilton C, Clippinger AJ, Maguire T, Alwine JC. Human Cytomegalovirus Induces Multiple Means To Combat Reactive Oxygen Species Human Cytomegalovirus Induces Multiple Means To Combat Reactive Oxygen Species. J Virol. 2011;85:12585–12593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05572-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Turunen MM, Dunlop TW, Carlberg C, Väisänen S. Selective use of multiple vitamin D response elements underlies the 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated negative regulation of the human CYP27B1 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2734–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Söderberg-Nauclér C, Streblow DN, Fish KN, Allan-Yorke J, Smith PP, Nelson JA. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus in CD14(+) monocytes is differentiation dependent. J Virol. 2001;75:7543–54. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7543-7554.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Campbell GR, Spector SA. Toll-like receptor 8 ligands activate a vitamin D mediated autophagic response that inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003017. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Shin D-M, Yuk J-M, Lee H-M, Lee S-H, Son JW, Harding CV, Kim J-M, Modlin RL, Jo E-K. Mycobacterial lipoprotein activates autophagy via TLR2/1/CD14 and a functional vitamin D receptor signalling. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1648–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Landais I, Pelton C, Streblow D, DeFilippis V, McWeeney S, Nelson JA. Human Cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p Targets TLR2 and Modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB Signaling Pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004881. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dobnig H, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, Renner W, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Kinkeldei J, Boehm BO, Weihrauch G, Maerz W. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1340–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]