Abstract

The present work investigates the capability of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) in enhancing the intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of the g-C3N4 nanosheets (NSs). We found that ssDNA adsorbed on g-C3N4 NSs could improve the catalytic activity of the nanosheets. The maximum reaction rate of the H2O2-mediated TMB oxidation catalyzed by the ssDNA-NSs hybrid was at least 4 times faster than that obtained with unmodified NSs. The activity enhancement could be attributed to the strong interaction between TMB and ssDNA mediated by electrostatic attraction and aromatic stacking and by both the length and base composition of the ssDNA. The high catalytic activity of the ssDNA-NSs hybrid permitted sensitive colorimetric detection of exosomes if the aptamer against CD63, a surface marker of exosome, was employed in hybrid construction. The sensor recognized the differential expression of CD63 between the exosomes produced by a breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and a control cell line (MCF-10A). Moreover, a similar trend was detected in the circulating exosomes isolated from the sera samples collected from breast cancer patients and healthy controls. Our work sheds lights on the possibility of using ssDNA to enhance the peroxidase-like activity of nanomaterials and demonstrates the high potential of the ssDNA-NSs hybrid in clinical diagnosis using liquid biopsy.

Graphical abstract

Recently, a variety of nanomaterials, such as the nanoparticles of Fe3O4,1,2 gold,3 cerium oxide,4 carbon-based nanotubes5 or graphene oxide nanosheets,6 and the transition-metal dichalcogenides7 have been observed to possess unique catalytic activities that mimic natural enzymes, termed nanozymes.8,9 Compared to biological enzymes, nanozymes are more stable, less expensive, and easier to store, with a few showing higher catalytic activity.10 These advantageous features encourage extensive exploration of the applications of nanozymes in diverse areas including biosensing, imaging, and therapeutics over the past few decades.11,12 However, it remains challenging to obtain nanozymes that enhance the catalytic activity, which greatly limits the scope and performance of their applications.13–15 The typical approaches to promote the catalytic activity of nanozymes are to construct hybrid nanostructures or to combine the nanozymes with a natural enzyme.16 However, these strategies usually require rather demanding conditions such as high temperature, toxic organic solvents, or complicated assembly processes. Alternatively, a recent finding has shown that single-stranded DNA can enhance the peroxidase-like activity of the Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) if used to modify the MNPs.17,18 In this case, the negatively charged phosphate backbone and bases of DNA can increase the binding of the peroxidase substrate, TMB, to the Fe3O4 MNPs, thus facilitating its oxidation in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. This elegant work points out the direction of employing simple molecules for activity enhancement of nanozymes to be more effectively used in sensing, imaging, or therapeutic areas.

Graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets (g-C3N4 NSs) are a type of graphene-like, carbon-based two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterial, which has been explored for various applications.19–22 In particular, the high surface-area-to-volume ratio and large band gap of ca. 2.7 eV make them efficient, metal-free catalysts for hydrogen evolution under visible light.23,24 Like other carbon nanomaterials, g-C3N4 NSs were found to possess intrinsic peroxidase-like activity and employed for the detection of glucose in serum or uric acid in urine.25,26 Furthermore, just like other nanomaterials,27–29 this material has been demonstrated to selectively adsorb single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) but not double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), which can be combined with their ability to quench fluorophores to design fluorescence sensors for nucleic acids.30

Inspired by the promising capability of DNA in enhancing the peroxidase-like activity of nanozymes and the excellent affinity of g-C3N4 NSs to ssDNA, we have designed a novel hybrid nanozyme by coupling g-C3N4 NSs with ssDNAs and observed increased catalytic activity for TMB oxidation. We also demonstrate the utility of this new nanozyme by employing it for simple and sensitive detection of exosomes in biological samples. Exosomes are extracellular vesicles with diameters ranging from 30 to 100 nm that are secreted from many cell types and typically carry cellular cargoes like proteins and nucleic acids.31 Since they are present in the circulation system and play important roles in cell–cell communication and disease development,32,33 they are excellent candidates as noninvasive biomarkers for disease diagnosis.34–36 Therefore, a simple, high-sensitivity, and low-cost detection strategy for exosomes is of great significance in speeding up the implementation of liquid biopsy in patient care. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to develop colorimetric detection of exosomes in human serum.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Materials

Cyanamide, thrombin, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), 3,3′,5,5′- tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), 30 wt % H2O2 solution, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). 5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline-N-Oxide (DMPO) was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.). Recombinant Human CD63 Protein was bought from Novus Biologicals, LLC (Littleton, CO, U.S.A.). Cell lines MCF-7 Cells and MCF-10A cells were bought from the Cell Bank of the Committee on Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Minimal essential growth medium (MEGM) and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 cell culture medium were purchased from Thermo Scientific HyClone (MA, U.S.A.). The DNA probes used in this study, all HPLC-purified and lyophilized, were synthesized by TaKaRa Biotech. Inc. (Dalian, China). The sequences of these probes are shown in Table S1. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water was obtained through a Millipore Milli-Q water purification system (Billerica, MA, U.S.A.) and had an electric resistance >18.25 MΩ.

Synthesis of g-C3N4 NSs

The detailed experimental procedure for preparing g-C3N4 NSs is provided in the Supporting Information.

Instruments and Characterization

All the used instruments for characterizing g-C3N4 NSs were almost consistent with those described in our previous reports.22 All the experimental details are supplied in the Supporting Information. The electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra were recorded on an X-Band ESR Spectrometer (Bruker, MA, U.S.A.).

DNA Accelerating Peroxidase Activity Assays

To prepare ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid materials, 10 μL of ssDNA solution of different concentrations, 10 μL of 100 μg/mL g-C3N4 NSs, 10 μL of 200 mM NaAc-HAc buffer (pH 4.0) and 60 μL of ultrapure water were mixed and incubated for 30 min in the dark under mild vortexing. Subsequently, 10 μL of TMB in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution (5 mM) and 10 μL of 50 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were injected into the above mixture to initiate the oxidation reaction for an additional 30 min at 40 °C in the dark. The absorption spectra were collected by UV2450 UV–visible absorption spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan).

Cell Culture and Preparation of Exosomes

Breast cancer cells MCF-7 were cultured in PRMI 1640 supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS. Nontumorigenic MCF-10A cells were cultured in MEGM containing 10% exosome-depleted FBS and cholera toxin. All cell lines were placed in a humidified incubator containing 5 wt %/vol CO2 at 37 °C. Exosomes were extracted from the cell culture medium after 48 h incubation according to the standard ultracentrifugation method with slight modification.37 In brief, the cell culture medium was centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min, 2000g for 20 min, and 110 000g for 45 min to sequentially remove intact cells, cell debris, and protein. Subsequently, the supernatant was centrifuged at 110 000g for 2 h to sediment the exosomes. Lastly, the sediment exosomes were resuspended in 1× PBS and stored in −80 °C before further use. Exosome extraction from human serum was carried out with the following procedure: first, serum samples were centrifuged at 3000g for 30 min; second, the supernatant was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter memberane and centrifuged at 110 000g for 60 min to obtain the exosome sediment; last, the sedimented exosomes were resuspended in 1× PBS.

Characterization and Quantification of Exosomes

The collected exosomes from MCF-7 cell culture supernatant were loaded on 400 mesh carbon grids. They were stained with 2.5% uranyl acetate and embedded with 1% methyl cellulose. The grid was then allowed to dry completely at room temperature. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was then executed to characterize the morphology of obtained exosomes. The hydrodynamic radius and concentration of the purified exosomes were quantified by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) NS 300 instrument (Malvern Instruments, U.K.).

Exosome Detection

Briefly, to make sure DNA aptamers can be adsorbed onto the NSs, 10 μL of 3 μM CD63 aptamer and 10 μL of 100 μg/mL g-C3N4 NSs were mixed by vortexing. The same number of exosomes from different cell lines or human sera were added to the mixtures and vortexed, followed by the addition of 10 μL of 5mM TMB and 10μL of 50 mM H2O2 in 20 mM NaAc-HAc buffer (pH 4.0) until the final volume reached 100 μL. The resulting solutions were kept at 40 °C for 30 min in the dark. Finally, the absorbance at 652 nm was recorded by using UV2450 UV–visible absorption spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan)

Results and Discussion

Experimental Scheme

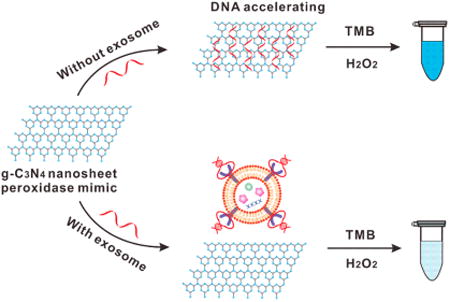

The overall design is illustrated in Scheme 1. Initially, the ssDNA aptamers for CD63 are adsorbed onto g-C3N4 NSs, and can enhance their intrinsic peroxidase activity, accelerating the oxidation of 3,3′,5,5′- tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) by H2O2 and generating the product with an intense blue color. In the presence of the exosomes carrying the surface protein of CD63, the ssDNA aptamer binds onto the exosomes in a folded structure that has lower affinity for g-C3N4 NSs, and could no longer enhance the nanozyme's peroxidase activity. TMB oxidation under the same reaction conditions yields lower amounts of the colored product. Qualitative detection can be performed by the naked eye; and measurement by visible absorbance at the product's λmax can lead to absolute quantification of exosomes based on the amount of CD63.

Scheme 1. Illustration of DNA Aptamer Accelerating the Intrinsic Peroxidase-Like Activity of g-C3N4 NSs for the Detection of Exosomes.

Characterization of Two-Dimensional (2D) g-C3N4 NSs

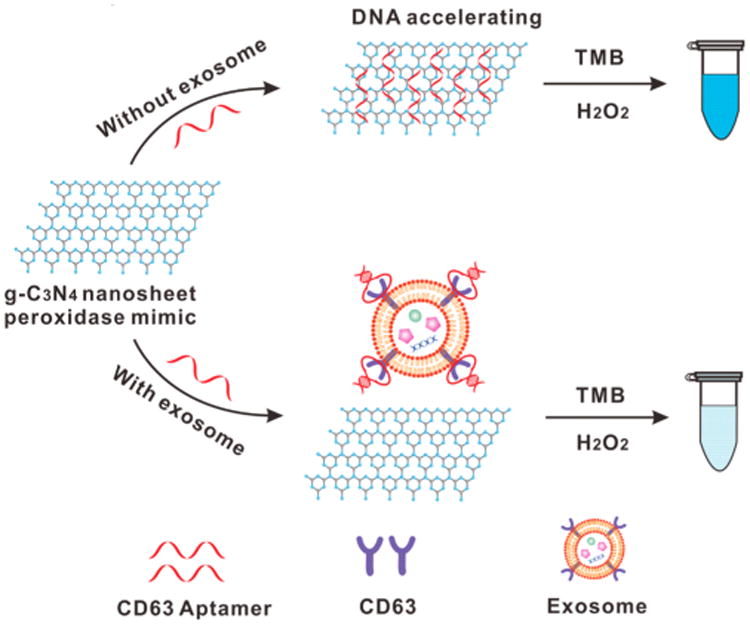

Various approaches were employed to characterize the assynthesized 2D g-C3N4 NSs. Results from transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 1A) and scanning electron microscope (SEM, Figure S1, Supporting Information) showed that the g-C3N4 NSs presented a planar sheet structure with the average diameter of about 120 nm. A slightly larger hydration size ∼140 nm was detected by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Figure S2, Supporting Information). The XRD spectrum (Figure 2B) showed a strong peak at 27.4 degree, a characteristic stacking peak of the π-conjugated layers and indexed for graphitic materials as the (002) peak, which is in good agreement with that of g-C3N4 in the previous report.19 Analysis by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Figure 1C,D) revealed that the thickness of the nanosheets was about 1.5 nm, which indicated that they mainly comprised of a single layer. The π-conjugated, atomic layer of g-C3N4 NSs support that the NSs should provide the largest specific surface area for the adsorption of ssDNA. Their surface composition was identified by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Figure 1E). The ratio of nitrogen to carbon was calculated to be 1.36, close to the theoretical value of 1.33, indicating high material purity. The relatively high oxygen content could be attributed to adsorption of oxygen on g-C3N4 NSs surfaces when using chemical oxidation and liquid exfoliation. In addition, FT-IR analysis also showed characteristic bands for the nanosheets (Figure S3, Supporting Information).38 These results proved that g-C3N4 NSs were successfully synthesized.

Figure 1.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of g-C3N4 NSs acquired with FEI Tecnai12 TEM. (B) The typical powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of g-C3N4 NSs. (C) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of g-C3N4 NSs. (D) The height profile of corresponding section of (C). (E) Survey X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of g-C3N4 NSs. (F) UV–vis absorption spectrum of g-C3N4 NSs solution.

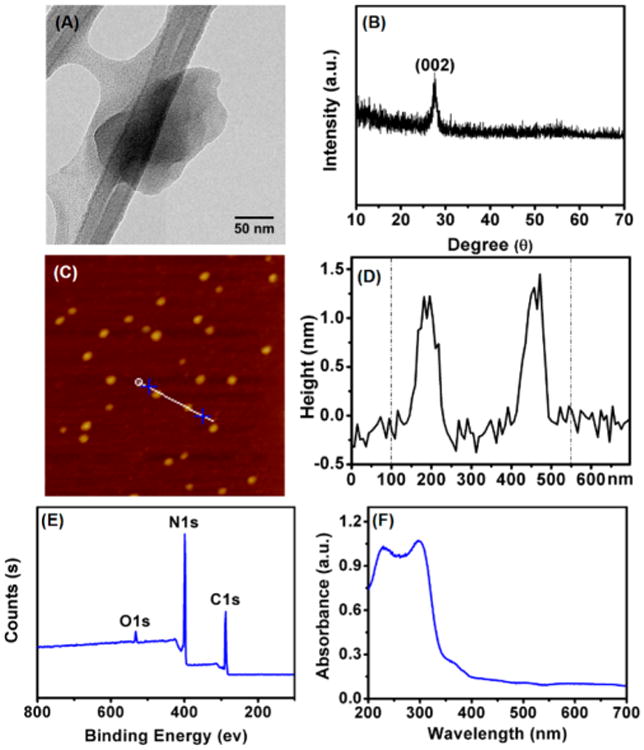

Figure 2.

(A) Absorption spectra obtained from catalytic reactions: (a) g-C3N4 NSs, TMB with H2O2 (black); (b) g-C3N4 NSs, dsDNA (Scr DNA20 A plus Scr DNA20 B), TMB with H2O2 (red); (c) g-C3N4 NSs, ssDNA (Scr DNA20 A), TMB with H2O2 (blue). Insets: photographs of corresponding reaction mixtures. (B) Acquired absorbance value at 652 nm from oxidation reactions in the presence of g-C3N4 NSs, TMB with H2O2 and (a) blank; (b) protein thrombin; (c) thrombin aptamer, protein thrombin; (d) thrombin aptamer. (C) The variation of OD at 652 nm as a function of different pH values with ssDNA (black) and without ssDNA (green). (D) Absorbance (OD at 652 nm) versus different ssDNA concentrations. Error bars indicated standard deviations across three repetitive assays. Otherwise specified, the used ssDNA sequence was Scr DNA20 A.

The photoluminescence properties of g-C3N4 NSs solution was also evaluated to confirm no spectral overlap between the NSs and the intended oxidation product of TMB. As can be seen in Figure 1F, g-C3N4 NSs did not show any obvious absorption in the visible light region due to the large 2.70 eV band gap,20 and emits at 432 nm under excitation from 220 to 410 nm (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Such fluorescent property should only be observed on nanosheets with only one or two layers, further confirming the NSs have large specific surface area.20 In addition, the as-synthesized g-C3N4 NSs solution can be stored for several months with no sign of degradation if sealed and kept in a dark environment at room temperature. Such a high stability makes it favorable for biomedical and biosensing applications.

Accelerating Peroxidase Mimicking Activity of g-C3N4 NSs Using ssDNA

We confirmed that the NSs synthesized in our hands also exhibited the peroxidase mimicking activity and optimized the reaction conditions, such as concentrations of TMB and H2O2 concentration, as well as reaction temperature, to achieve maximum enzymatic activity. According to previous reports, visible light could influence the peroxidase-like catalytic activity of g-C3N4 NSs;39 thus, we conducted all catalytic reactions in the dark. It was found that with 500 μM TMB, 5 mM H2O2, and 40 °C, the highest catalytic activity, as observed by the most intense absorption occurred at λ = 652 nm was attained (Figure S5, Supporting Information), and they were chosen as the optimal experimental conditions employed in the following experiments.

The strong interaction between ssDNA and g-C3N4 NSs has been previously reported.30 Therefore, we went on to investigate the effect of ssDNA adsorption on the peroxidase-like activity of g-C3N4 NSs with TMB and H2O2 as the substrates. As shown in Figure 2A, the unmodified g-C3N4 NSs only slowly catalyzed TMB oxidation by H2O2, producing a moderate absorption peak at 652 nm after 30 min. However, when the 20-nt ssDNA (Scr DNA20 A) was added to the reaction mixture, the peak intensity increased by ∼6.2-fold. However, in a control experiment, when only g-C3N4 NSs, ssDNA, or the ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid was added to TMB solution (in the absence of H2O2), the absorbance at 652 nm displayed negligible change (Figure S6, Supporting Information), indicating no oxidation reaction occurred. In addition, if the complementary ssDNA was added to the reaction mixture, the resultant absorbance (Abs) at λ = 652 nm dropped back to the same level as the g-C3N4 NSs (Figure 2A, red line). Formation of the dsDNA should have released the ssDNA from the g-C3N4 NSs, and thus, no enhanced catalytic activity was observed. Similarly, if the ssDNA was an aptamer, for example, the aptamer for thrombin, a significant difference in the enzymatic activity was observed with or without the presence of its target. In the presence of thrombin, the absorbance of the oxidation product λ = 652 nm was comparable to that of the bare g-C3N4 NSs and the NSs incubated with thrombin itself, > 4-fold lower than that obtained with the g-C3N4 NSs preincubated with the thrombin aptamer (29-nt) (Figure 2B).

It was observed that the enhancement in enzymatic activity is dependent on solution pH. Similar to the natural enzyme of horseradish peroxidase (HRP), highest catalytic activity of the bare NSs was observed at pH 4 (green bars, Figure 2C), in agreement with what was found in literature.25,26 With the addition of ssDNA, the trend of pH dependence remained the same, with pH 4.0 being the optimal pH, but the activity was enhanced (gray bars, Figure 2C). It is interesting to note that at pH 6, the absorbance change of TMB with DNA-modified g-C3N4 NSs is comparable to that of unmodified g-C3N4 NSs at pH 4. Therefore, adsorption of ssDNA on the NSs can expand their applications over a broader pH range than the bare materials.

The signal response is proportional to ssDNA concentration if fixing the concentration of g-C3N4 NSs. As shown in Figure 2D, the absorbance at λ= 652 nm increased linearly with increasing concentrations of the 20-nt ssDNA incubated with 10 μg/mL g-C3N4 NSs. All other reaction conditions were kept the same as in Figure 2A. The signal increase reached a plateau when the ssDNA concentration was beyond 400 nM. As low as 10 nM ssDNA can be detected. All of the above results point out that, adsorption of ssDNA on the g-C3N4 NSs produces a hybrid nanozyme that is suitable for development of biosensors.

Mechanism of DNA Accelerating the Peroxidase Activity of g-C3N4 NSs

To better understand the mechanism of activity enhancement, we carried out the steady-state kinetic assay and compared the kinetic parameters of HRP, bare g-C3N4 NS, and the g-C3N4 NSs preincubated with the 20-nt ssDNA, which were acquired by varying the concentration of one substrate (TMB or H2O2) while keeping the other one fixed (Figure S7, Supporting Information). The oxidation reaction catalyzed by ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid or the bare g-C3N4 NSs followed the typical Michaelis–Menten behavior toward both substrates (Figure S7A–D, Supporting Information). Double-reciprocal Michaelis–Menten curves were plotted (Figure S7E to H, Supporting Information) and fitted to the Lineweaver–Burk eq 1/ν = (Km/Vmax) × (1/[S]) + 1/Vmax, where ν is the initial velocity, Km is the Michaelis–Menten constant, Vmax is the maximal reaction velocity, and [S] is the concentration of the substrate. The Km and Vmax were calculated using the aforementioned equation and summarized in Table 1. As shown, the apparent Km values of bare g-C3N4 and ssDNA/g-C3N4 using H2O2 as the substrate were similar and they were both larger than that of HRP.1 However, for the substrate of TMB, the apparent Km value of ssDNA/g-C3N4 was 5.1-fold and 3.9-fold lower than that of bare g-C3N4 and HRP, respectively, indicating that the ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid had a higher affinity to TMB than the bare g-C3N4 NSs and HRP.

Table 1. Comparison of the Apparent Michaelis-Menten Constant (Km) and Maximum Reaction Rate (Vmax) of the Catalytic Reactions.

| catalyst | substrate | Km (mM) | Vmax (M/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRP | H2O2 | 3.70 | 8.71 × 10−8 |

| HRP | TMB | 0.43 | 10.00 × 10−8 |

| bare g-C3N4 | H2O2 | 4.68 | 7.23 × 10−8 |

| bare g-C3N4 | TMB | 0.56 | 14.83 × 10−8 |

| ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid | H2O2 | 4.61 | 7.39 × 10−8 |

| ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid | TMB | 0.11 | 58.53 × 10−8 |

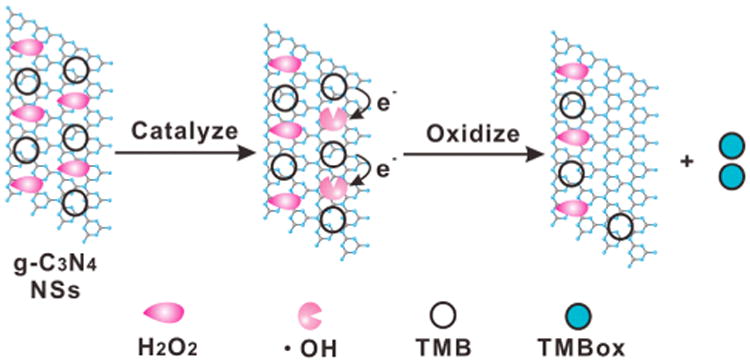

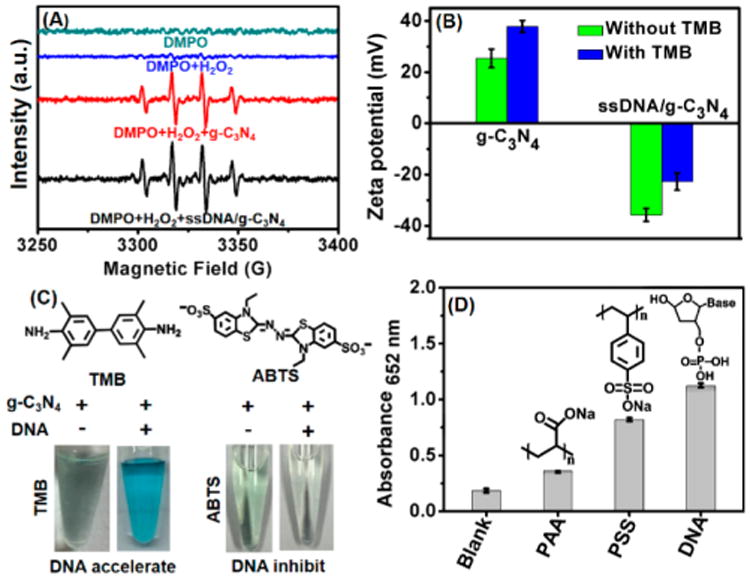

Previous reports have proposed a possible catalytic mechanism of g-C3N4 NSs that follows two steps: 1) H2O2 molecules interact with a peroxidase mimic to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and 2) TMB oxidized by •OH forms a blue color product TMBox (Scheme 2). To find out whether •OH is generated and if ssDNA can increase the amount of •OH produced, electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy was conducted by specifically trapping •OH with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO). As seen in Figure 3A, addition of H2O2 produced weak, characteristic peaks of the typical DMPO-•OH adducts, indicating the base-level decomposition of H2O2 in solution. The peak intensity increased dramatically while g-C3N4 was added to the reaction system, and the peak intensity ratio of 1:2:2:1 can be clearly observed, supporting that g-C3N4 can catalyze generation of •OH from H2O2 decomposition. However, the ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid did not show a significant increase in •OH production compared to the NSs, indicating that the enhanced enzymatic activity of this hybrid is not originated from accelerated decomposition of H2O2. This also agrees with the Km and Vmax values for H2O2 shown in Table 1.

Scheme 2. Proposed Catalytic Mechanism for the g-C3N4 NSs-H2O2-TMB System.

Figure 3.

(A) ESR spectra of different reaction systems with DMPO as the spin trap. (B) Zeta potential of bare g-C3N4 NSs and ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid at pH 4.0 with or without the addition of TMB. (C) Top: chemical structure of TMB and ABTS. Bottom: photograph of catalytic oxidation of TMB or ABTS by g-C3N4 NSs in the presence or absence of ssDNA. (D) Comparison of enzyme mimetic activity of g-C3N4 NSs coated with different negatively charged polymers. Error bars indicated standard deviations across three repetitive assays. Insets: corresponding chemical structure of polymers. Otherwise specified, the used ssDNA sequence was Scr DNA20 A.

Since ssDNA adsorption does not influence the reactivity of H2O2, the contribution of the other substrate, TMB, was then investigated. TMB adsorption on the g-C3N4 NS was evaluated by zeta-potential measurement, because the nonoxidized TMB with two amino groups has a pKa of ∼4.2 and is partially positively charged at pH 4. However, adsorption of ssDNA completely reversed the charge from positive to negative. With the addition of TMB, the surface charge of both the bare g-C3N4 NSs and the ssDNA/g-C3N4 NSs hybrid become more positive (Figure 3B). The conjugated structure of TMB could help with its adsorption on the bare g-C3N4 NSs and its partial positive charge enhances its binding to the ssDNA-modified g-C3N4 NSs. The capability of the substrate to be adsorbed by the ssDNA-modified g-C3N4 NSs surface is important for the enhanced catalytic activity. The negatively charged peroxidase substrate, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), which could be repelled by the negatively charged ssDNA, actually exhibits inhibition of the enzymatic activity of g-C3N4 NSs. As shown in Figure 3C, after adding H2O2, ABTS was oxidized by the unmodified g-C3N4 NSs but not by the ssDNA modified g-C3N4 NSs. Since electrostatic interaction can be reduced by an increase in ionic strength, ABTS oxidation by the ssDNA/g-C3N4 hybrid can be gradually recovered by adding Na+ to the solution (Figure S8, Supporting Information).

Importance of the electrostatic interaction between TMB and the adsorbed molecule on the NSs surface was also illustrated by the activity difference between the NSs modified with various negatively charged polymers: ssDNA, poly(acrylic acid) (PAA, Mw ∼ 5100) and polystyrenesulfonate (PSS, Mw ∼ 70 000). All negatively charged polymer-coated nanosheets respectively produced more oxidation product of TMB than the bare g-C3N4 NSs, with ssDNA being the most effective in activity enhancement, followed by PSS and PAA (Figure 3D). Compared with PAA, the benzene ring structure of PSS facilitate the interaction between g-C3N4 NSs and the polymer by π–π stacking. As a result, higher enzyme activity of PSS-modified NSs can be observed than PAA-modified NSs.

The sequence and length of the ssDNA can strongly affect activity enhancement while keeping the total concentration of nucleosides constant. We compared TMB oxidation by the g-C3N4 NSs modified with the 20-nt homo DNAs of A20, T20, C20, and G20 at pH 4.0 (20 mM acetate buffer). The results showed that the reaction rate was dependent on DNA sequence (Figure S9A, Supporting Information), following the trend of C20 > G20 > T20 > A20 > no DNA. In addition to the negatively charged backbone, DNA bases may also interact with TMB via hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking. Cytosine may have the strongest interaction with TMB and thus behaves the best in enhancing enzymatic activity. The length of the ssDNA also impacts on the reaction rate (Figure S9B, Supporting Information). Among the NSs modified with poly Cn (C5, C10, C20 and C30), longer the ssDNAs, more oxidized TMB was generated under the identical reaction conditions. Like graphene, longer DNAs adsorb more readily to the g-C3N4 NSs due to the presence of more binding sites (i.e., the poly valent binding effect). Similarly, ssRNA can enhance enzymatic activity as well (Figure S10, Supporting Information). These results strongly imply that adsorption of ssDNA on the NSs is crucial for activity enhancement, which is impacted by both the length and sequence of the ssDNA. The 20-nt ssRNA and ssDNA behaved similarly and the amounts of TMB oxidation product generated were not statistically different from each other. Thus, more hybrid NSs can be designed with a variety of nucleic acid structures.

Detection of Exosomes with the ssDNA/g-C3N4 NSs Hybrid

As illustrated in Figure 2, the ssDNA/g-C3N4 NSs hybrid can catalyze TMB oxidation at a higher rate than the bare NSs. The amount of oxidation product generated under a fixed reaction condition is proportional to the concentration of ssDNA in the system, which could be changed by the presence of molecules with the capability to bind to ssDNA and remove it from the NS surface, such as the complementary DNA and DNA-binding proteins. These results indicated the possibility of applying the hybrid nanozymes for biomarker detection. The nanozymes should provide the advantages of high sensitivity in detection owing to the enhanced enzymatic activity and high simplicity in operation because of the colorimetric signal recognition scheme. In the present study, we applied the enzyme mimic to detect exosomes in biological samples. Circulating exosomes hold high promise as biomarkers in liquid biopsy because of their important functions in cell–cell communication and their cell-origin-mimicking contents that could reflect the health status of the parent cells.

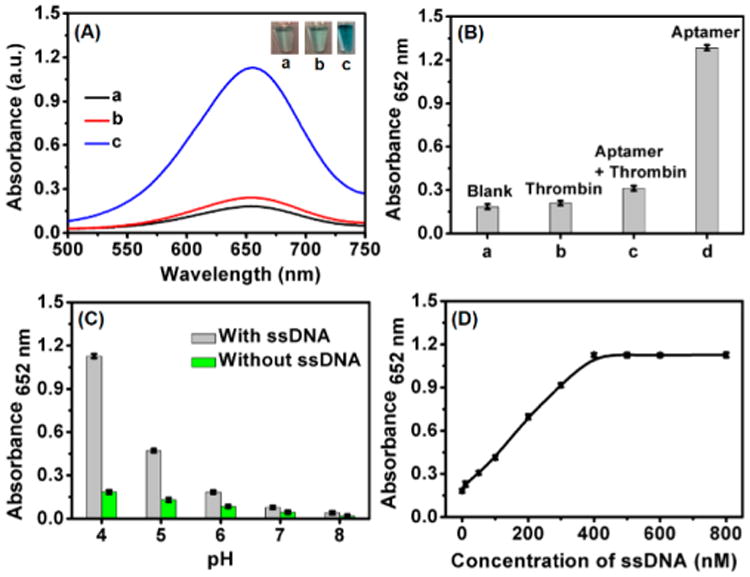

Exosomes were harvested from the exosome-free fetal bovine serum (FBS) applied to the MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells after 48-h incubation, and purified by a three-step centrifugation procedure using an ultracentrifuge. The morphology and size of the purified exosomes were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in Figure 4A, the vesicles appear spherical in shape with diameters ranging from 30 to 100 nm, consistent with previous reports.37 Size distribution and vesicle concentration were determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) at room temperature (Figure S11, Supporting Information). The median hydrodynamic diameter was found to be 100 nm and the concentration of acquired exosomes was about 1.65 × 109 particles/μL.

Figure 4.

(A) TEM image of exosomes. (B) The OD at 652 nm of reaction mixture with the addition of different components. (C) UV-vis absorption spectra of the proposed strategy in the absence and presence of different amounts of exosomes (from a to k: the amounts of exosomes are 0, 0.19, 0.48, 0.97, 1.45, 1.93, 2.41, 2.89, 3.38, 3.86, 4.35 × 107 particles/μL). Insets: digital images of corresponding reaction mixtures. (D) The selectivity toward secreted exosomes from different parent cells. Error bars indicated standard deviations across three independent experiments.

The common exosomal transmembrane protein CD63 was 40–43 Tchosen as the affinity handle for exosome recognition. The CD63 aptamer has the length of 32-nt and can be adsorbed by the NSs, forming the aptamer/g-C3N4 NSs hybrid. This material showed improved activity over the bare NSs in catalyzing TMB oxidation by H2O2. However, in the presence of 300 nM of CD63, the enzymatic activity decreased due to the release of the aptamer from NS surface after it bound to the target CD63 (Figure 4B). The enzymatic activity was not affected by the protein itself. The absorbance at λ = 652 nm from the oxidized TMB decreased proportionally with increasing concentration of the CD63-positive exosomes (from 0.19 × 107 particles/μL to 3.38 ×107 particles/μL) added to the reaction system (Figure 4C). Accordingly, the color change to the reaction solution was clearly observable by the naked eye (Insets of Figure 4C). Plotting the absorbance vs exosome concentration gave out a linear curve following the correlation equation of ΔA = 0.312 × CExosomes + 0.0174 (Figure S12 in Supporting Information), where the squared correlation coefficient (R2) is 0.9986 and the ΔA was defined as A0 – A (A0 and A were the OD at 652 nm in the absence and presence of exosomes, respectively). The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated as 13.52 × 105 particles/μL by using the 3σ method and was comparable to or better than the existing methods (Table S2 in Supporting Information). The detection time of ∼30 min was also comparable or shorter than existing assays.

We then investigated the capability of our sensor in differentiating the exosomes secreted by a breast cancer cell line (MCF-7 cells) and a nontumorigenic cell line (MCF-10A cells). According to reported literatures, the expression level of CD63 of in the MCF-7-derived exosomes was higher than that of the MCF-10A-derived exosomes.40–43 Indeed, much higher absorbance change at λ= 652 nm was detected with the exosomes produced from the MCF-7 cells than that from the MCF-10A cells while the same number of exosomes (3.38 × 107 particles/μL counted by NTA) were used (Figure 4D). These results prove that our aptamer/g-C3N4 NSs hybrid is a simple, stable, low-cost, and effective tool for exosome detection.

Our sensing platform can also detect exosomes isolated from clinical specimens. Exosomes isolated from serum samples were collected from breast cancer patients and healthy individuals. The same number of exosomes (3.65 × 107 particles/μL counted by NTA) from each sample was mixed with the DNA-NS hybrid, followed by addition of TMB and H2O2. As displayed in Figure 5, the exosomes collected from patient's serum generated a less intense blue color than those from the healthy donors, and the color difference between these samples was clearly discriminable by the naked eye (inset images in Figure 5). The averaged Abs change was about ∼2.5-fold higher for the exosomes collected from patients as compared to those from healthy controls. The increase may be a result of a higher expression level of CD63 on the surface of exosomes secreted by tumor cells than normal cells.

Figure 5.

Colorimetric detection of exosomes from serum of breast cancer patients (from a to d, gray bars) and healthy individuals (from e to h, green bars). Insets: digital images of corresponding reaction mixtures. Error bars were from three repeated measurements, and each letter represented the sample from one individual.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that ssDNA can accelerate the intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of g-C3N4 NSs. The hybrid material resultant from adsorbing the anti-CD63 aptamer onto the NSs permits sensitivie and colorimetric detection of exosomes originated from various sources. Switching the aptamer with other functional nucleic acids could produce new and simple sensing platforms for rapid detection of diverse biological targets with low-cost instrumentation.

Supplementary Material

Additional experimental details; SEM, DLS, FT-IR and fluorescence spectra for the nanosheets; evaluation of reaction rates under different conditions; steady-state kinetic study for the nanosheet and the DNA-nanosheet hybrid; evaluation of impact on reaction from DNA and RNA with different structures; size measurement of exosomes and detection curve by the nanosheets; table of DNA sequences and comparison of LODs of our method with other previous reports (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Y-M.W. received the financial support from the China Scholarship Council. The authors acknowledge the support by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA188991 to W.Z.; and the Research Training Grant in Environmental Toxicology from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES018827) to G.B.A This work was also supported by NSFC (21275045, 21190041), NCET-11-0121, and NSF of Hunan (12JJ1004) for J.-H.J. We also thank the Central Facility of Advanced Microscopy and Microanalysis and the IIGB Instrumentation facility of UCR for instrument usage.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.anal-chem.7b03335.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Gao L, Zhuang J, Nie L, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Gu N, Wang T, Feng J, Yang D, Perrett S, Yan X. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:577–583. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Z, Zhang X, Liu B, Liu JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5412–5419. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hizir MS, Top M, Balcioglu M, Rana M, Robertson NM, Shen F, Sheng J, Yigit MV. Anal Chem. 2016;88:600–605. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asati A, Santra S, Kaittanis C, Nath S, Perez JM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:2308–2312. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui R, Han Z, Zhu JJ. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:9377–9384. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Y, Qu K, Zhao C, Ren J, Qu X. Adv Mater. 2010;22:2206–2210. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin T, Zhong L, Song Z, Guo L, Wu H, Guo Q, Chen Y, Fu F, Chen G. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;62:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei H, Wang E. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:6060–6093. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35486e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin Y, Ren J, Qu X. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:1097–1105. doi: 10.1021/ar400250z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotov NA. Science. 2010;330:188–189. doi: 10.1126/science.1190094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z, Zhang C, Gao Q, Wang G, Tan L, Liao Q. Anal Chem. 2015;87:10963–10968. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Li F, Shen W, Liu X, Cui HJ. J Mater Chem C. 2016;4:3477–3484. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diez-Castellnou M, Mancin F, Scrimin P. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:1158–1161. doi: 10.1021/ja411969e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, He X, Yin JJ, Ma Y, Zhang P, Li J, Ding Y, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Chai Z, Zhang Z. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:1832–1835. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Zhao H, Chen S, Yu H, Quan X. ACS Nano. 2012;6:3142–3151. doi: 10.1021/nn3010922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu B, Liu J. Nano Res. 2017;10:1125–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B, Liu J. Chem Commun. 2014;50:8568–8570. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03264k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B, Liu J. Nanoscale. 2015;7:13831–13835. doi: 10.1039/c5nr04176g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Xie X, Wang H, Zhang J, Pan B, Xie Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18–21. doi: 10.1021/ja308249k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma TY, Tang Y, Dai S, Qiao SZ. Small. 2014;10:2382–2389. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian J, Liu Q, Asiri AM, Al-Youbi AO, Sun X. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5595–5599. doi: 10.1021/ac400924j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JW, Wang YM, Xu L, Duan LY, Tang H, Yu RQ, Jiang JH. Anal Chem. 2016;88:8355–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Maeda K, Thomas A, Takanabe K, Xin G, Carlsson JM, Domen K, Antonietti M. Nat Mater. 2009;8:76–80. doi: 10.1038/nmat2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du A, Sanvito S, Li Z, Wang D, Jiao Y, Liao T, Sun Q, Ng YH, Zhu Z, Amal R, Smith SC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4393–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja211637p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin T, Zhong L, Wang J, Guo L, Wu H, Guo L, Fu F, Chen G. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;59:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Q, Deng J, Hou Y, Wang H, Li H, Zhang Y. Chem Commun. 2015;51:12251–12253. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04231c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Sun X. Small. 2011;7:1562–1568. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu C, Zeng Z, Li H, Li F, Fan C, Zhang HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5998–6001. doi: 10.1021/ja4019572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Liu D, Hao S, Qu F, Ge R, Ma Y, Du G, Asiri AM, Chen L, Sun X. Anal Chem. 2017;89:2191–2195. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Wang W, Lei J, Xu N, Gao F, Ju H. Anal Chem. 2013;85:12182–12188. doi: 10.1021/ac403646n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Théry C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Budnik V, Ruiz-Cañada C, Wendler F. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:160–172. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tkach M, Théry C. Cell. 2016;164:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christianson HC, Svensson KJ, van Kuppevelt TH, Li JP, Belting M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17380–17385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304266110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong S, Park J, Pathania D, Castro CM, Weissleder R, Lee H. ACS Nano. 2016;10:1802–1809. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan S, Zhang L, Wang S, Liu Y, Wu C, Cui C, Sun H, Shi M, Jiang Y, Li L, Qiu L, Tan WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5289–5292. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou YG, Mohamadi RM, Poudineh M, Kermanshah L, Ahmed S, Safaei TS, Stojcic J, Nam RK, Sargent EH, Kelley SO. Small. 2016;12:727–732. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rong M, Lin L, Song X, Zhao T, Zhong Y, Yan J, Wang Y, Chen X. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1288–1296. doi: 10.1021/ac5039913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui Y, Ding Z, Liu P, Antonietti M, Fu X, Wang X. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:1455–1462. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22820j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Logozzi M, De Milito DA, Lugini L, Borghi M, Calabrò L, Spada M, Perdicchio M, Marino ML, Federici C, Iessi E, Brambilla D, Venturi G, Lozupone F, Santinami M, Huber V, Maio M, Rivoltini L, Fais S. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao H, Chung J, Balaj L, Charest A, Bigner DD, Carter BS, Hochberg FH, Breakefield XO, Weissleder R, Lee H. Nat Med. 2012;18:1835–1840. doi: 10.1038/nm.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshioka Y, Konishi Y, Kosaka N, Katsuda T, Kato T, Ochiya TJ. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2:20424. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Etayash H, Mc Gee AR, Kaur K, Thundat T. Nanoscale. 2016;8:15137–15141. doi: 10.1039/c6nr03478k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional experimental details; SEM, DLS, FT-IR and fluorescence spectra for the nanosheets; evaluation of reaction rates under different conditions; steady-state kinetic study for the nanosheet and the DNA-nanosheet hybrid; evaluation of impact on reaction from DNA and RNA with different structures; size measurement of exosomes and detection curve by the nanosheets; table of DNA sequences and comparison of LODs of our method with other previous reports (PDF)