Abstract

Purpose

The novel dual-action humanized IgG1 antibody MEHD7945A targeting HER3 and EGFR inhibits ligand-dependent HER dimer signaling. This phase I study evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antitumor activity of MEHD7945A.

Experimental Design

Patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelial tumors received escalating doses of MEHD7945A (1–30 mg/kg) every 2 weeks (q2w) until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. An expansion cohort was enrolled at the recommended phase II dose (14 mg/kg, q2w). Plasma samples, tumor biopsies, FDG-PET were obtained for assessment of pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamic modulation downstream of EGFR and HER3.

Results

No dose-limiting toxicities or MEHD7945A-related grade ≥ 4 adverse events (AE) were reported in dose-escalation (n = 30) or expansion (n = 36) cohorts. Related grade 3 AEs were limited to diarrhea and nausea in the same patient (30 mg/kg). Related AEs in ≥20% of patients ≤24 hours after the first infusion included grade 1/2 headache, fever, and chills, which were managed with premedication and/or symptomatic treatment. Pharmacodynamic data indicated target inhibition in 25% of evaluable patients. Best response by RECIST included 2 confirmed partial responses in squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck (SCCHN) patients with high tumor tissue levels of the HER3 ligand heregulin; 14 patients had stable disease ≥8 weeks, including SCCHN (n = 3), colorectal cancer (n = 6), and non–small cell lung cancer (n = 3).

Conclusions

MEHD7945A was well-tolerated as single agent with evidence of tumor pharmacodynamic modulation and anti-tumor activity in SCCHN. Phase II studies were initiated with flat (nonweight-based) dosing at 1,100 mg q2w in SCCHN and colorectal cancer.

Introduction

Dysregulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (ErbB, HER) family plays an important role in tumorigenesis (1, 2). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, HER1) and HER2 have been successfully targeted for the treatment of cancer. HER3 is a unique receptor that has impaired kinase activity and requires heterodimerization with other family members for signaling (3, 4). HER3 directly couples the PI3K–Akt pathway via six docking sites for the p85 subunit of PI3K, making it the most potent activator of the survival pathway and HER family in general. HER3 has been described as a central mediator of resistance to HER-targeted therapeutics (5–7).

EGFR is another major player in tumorigenesis; EGFR-blocking agents are approved for treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), pancreatic cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), and colorectal cancer (8).

Extensive crosstalk among the HER family receptors contributes to the activation of overlapping downstream signaling pathways (9, 10). Interruption of HER receptor–driven tumorigenesis may require the blockade of multiple HER-driven cascades. Thus, we hypothesized that inhibition of signaling of multiple HER family receptors offers superior efficacy and will potentially overcome de novo and/or acquired resistance to currently available EGFR-directed therapies.

The anti-HER3/EGFR humanized IgG1 antibody MEHD7945A has dual binding specificity that targets both HER3 and EGFR (11). Each antigen-binding arm binds to two unique epitope targets with high affinity, and inhibits signaling from all major ligand-dependent HER dimer pairs. Different from bi-specific agents, the presence of two identical Fab arms in MEHD7945A raises the possibility that for a given receptor density, any combination of EGFR and HER3 levels should be recognized with near-equivalent avidity (11). Furthermore, MEHD7945A can bind to Fcγ receptors and elicit antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. MEHD7945A has demonstrated saturable single-agent activity in multiple tumor models (12), including models with intrinsic or acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. In nonclinical safety studies, MEHD7945A was well tolerated in cynomolgus monkeys up to 30 mg/kg weekly for 12 weeks, with minimal or no rash observed (data not shown). Here, we evaluated MEHD7945A in patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelial tumors.

Materials and Methods

This was a phase I, multicenter, international, open-label study with two stages: a dose-escalation stage and an expansion stage. The protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards before patient recruitment and conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonization E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. Clinicaltrials.gov registration number is NCT01207323.

Study population

Patients ≥18 years of age were eligible after providing informed consent. Key inclusion criteria included histologically documented, incurable, locally advanced, or metastatic epithelial malignancy that had progressed despite standard therapy or for which no standard therapy existed; in the expansion stage, indications were limited to colorectal cancer, NSCLC, SCCHN, or pancreatic cancer; disease had to be evaluable or measurable by RECIST v1.0; ECOG performance status of 0 to 1. Patients had adequate hematologic, renal, or hepatic function as well as archival tumor tissue. Most relevant exclusion criteria included (i) severe, uncontrolled systemic, cardiac, lung, or liver disease; or (ii) primary central nervous system (CNS) malignancy or untreated/active CNS metastases.

Study design

The dose-escalation stage was designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of MEHD7945A administered i.v. every 2 weeks (q2w). Six dose levels (1, 4, 10, 15, 22, and 30 mg/kg) were evaluated to determine the MTD and to identify the recommended phase II dose (RP2D). Dose cohorts ≥10 mg/kg were expanded to 6 patients each (from n = 3 for 1 and 4 mg/kg) for added safety and pharmacokinetic assessment. Based on the achieved serum concentrations in patients and pharmacokinetics from nonclinical tumor models, the predicted efficacious exposure was reached at the 8 to 12 mg/kg dose level. However, in the absence of dose-limiting toxicity, escalation was continued up to maximum of 30 mg/kg to specifically evaluate the dose–response relationship to rash.

Patients were enrolled in an expansion stage at the RP2D of 14 mg/kg i.v. q2w to better characterize the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics variability of this dose, and assess preliminary antitumor activity. MEHD7945A administration was discontinued in patients who experienced a dose-limiting toxicity, disease progression, or other unacceptable toxicity.

Study treatment

The dose of MEHD7945A (supplied by Genentech) for each patient was dependent on the dose level assignment and the patient's weight on or within 14 days of day 1 of each cycle. MEHD7945A was administered over 90 ± 10 minutes for the first two doses. Subsequent doses were administered over 30 ± 10 minutes (for dose levels <10 mg/kg) or 60 ± 10 minutes (for dose levels ≥10 mg/kg).

Study assessments

Safety

Safety was evaluated according to NCI CTCAE v4.0, on days 1 and 8 of each cycle, and study completion. Dose-limiting toxicities were assessed for 28 days and included drug-related grade ≥3 hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities with exception of grade 3 rash or diarrhea that resolved to grade ≤ 2 within 7 days with standard-of-care therapy; grade 3 nausea or vomiting, in the absence of premedication, which responded to standard-of-care therapy; grade 3 fatigue in patients with baseline grade ≤ 2 fatigue; grade 3 hypomagnesemia that responded to treatment with magnesium supplement; and alopecia of any grade.

Pharmacokinetics

Serum MEHD7945 pharmacokinetics was evaluated during cycle 1 at predose, 0.5 and 4 hours, and 1, 3, and 7 days after dose (13). Additional samples were collected at predose, 0.5 hours, and 7 days (cycles 2 and 4 only) after dose for cycles 2, 3, 4, 6, and every 4 cycles thereafter, and at the study termination visit. MEHD7945A concentration was determined using a qualified ELISA assay with the minimum quantifiable concentration of 150 ng/mL. Pharmacokinetic parameters were derived from non-compartmental analysis (WinNonlin version 5.2.1) using the complete cycle 1 serum concentration–time profile of MEHD7945A from 66 patients.

Serum anti-MEHD7945A antibody (ATA) samples were collected before MEHD7945A infusion on day 1 of cycles 1, 2, 4, and at the study termination visit, and were analyzed using a validated bridging antibody immunoassay that could detect 249 ng/mL of surrogate anti-MEHD7945A positive-control antibody in the absence of MEHD7945A.

Pharmacodynamics and clinical activity

To assess pharmacodynamic effects on tumor EGFR and HER3 signaling, paired tumor biopsies were obtained at baseline and during cycle 2 from all patients in the expansion stage who had tumor lesions that could be safely biopsied and were obtained on a voluntary basis in dose-escalation stage. Tumor samples were assessed for phosphorylated proline-rich AKT substrate 40 (pPRAS40), phosphorylated ERK (pERK), and phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (pRPS6).

To assess the effects of MEHD7945A on tumor metabolism or as a surrogate marker of response to therapy, 18F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET scans were obtained in accordance to an imaging charter in both the dose-escalation and expansion stages at baseline and repeated during cycle 2 if at least one PET-assessable lesion was observed at baseline. A FDG-PET partial metabolic response (PMR) was defined as a decrease of ≥20% in measured maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of up to five tumor regions of interest.

MEHD7945A activity was evaluated by CT scans every 8 weeks, with confirmation of objective response ≥4 weeks after initial documentation (per RECIST v1.0).

At study entry, tumor tissue was collected and subsequently tested for selected molecular markers. Given its wide dynamic range as a potentially predictive biomarker, HRG (alpha and beta forms of neuregulin 1; ref. 14) mRNA expression analyses from archival or cycle 1 day 14 tissue were conducted as previously described (16) in 52 patients. Other biomarker analyses included EGFR and KRAS mutation status.

Statistical methods

Design considerations were not made with regard to explicit power and type I error, but to obtain preliminary safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic information. For the safety, all patients who received any amount of MEHD7945A were included. For activity analyses, all patients with measurable disease at baseline were included. Objective response was defined as a complete response (CR) or PR (partial response), as determined by investigator assessment using RECIST and confirmed by repeat assessments ≥4 weeks after initial documentation. Progression-free survival (PFS; and duration of a patient's stable disease by RECIST) was defined as the time from the first day of study treatment to disease progression or death within 60 days of the last study drug administration, whichever occurred first. If a patient did not experience progressive disease or die, or was lost to follow-up, PFS survival was censored at the day of the last tumor assessment.

Results

Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics

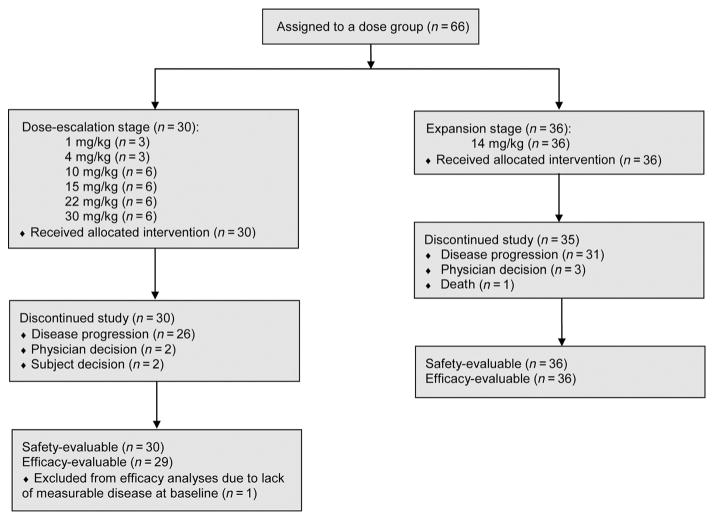

From November 2010 to October 2011, 66 patients were enrolled at 6 sites in the United States and Spain (Fig. 1). The cutoff date for analysis was December 3, 2013, resulting in a median treatment duration of 6.1 weeks (range, 0.1–113) for 66 patients. The baseline demographics are shown in Table 1. Most patients had received multiple prior regimens of systemic therapy. Most patients (52%) received prior anti-EGFR therapies (mostly cetuximab, panitumumab, or erlotinib).

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

| 1 mg/kg (n = 3) | 4 mg/kg (n = 3) | 10 mg/kg (n = 6) | 15 mg/kg (n = 6) | 22 mg/kg (n = 6) | 30 mg/kg (n = 6) | Dose expansion 14 mg/kg (n = 36) | Total (N = 66) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 50 (46–63) | 76 (60–80) | 61 (48–69) | 63 (53–76) | 57 (49–74) | 55 (44–80) | 63 (35–87) | 61 (35–87) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) | 11 (31) | 27 (41) |

| Male | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 3 (50) | 5 (83) | 2 (33) | — | 25 (69) | 39 (59) |

| ECOG status | ||||||||

| 0 | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 13 (36) | 27 (41) |

| 1 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 23 (64) | 39 (59) |

| Prior systemic therapy | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 36 (100) | 66 (100) |

| Number of prior systemic regimens, median (range) | 2 (2–3) | 6 (1–9) | 5 (2–6) | 3 (1–4) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (4–11) | 4 (1–8) | 4 (1–11) |

| Prior anti-EGFRa | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 22 (61) | 34 (52) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 24 (67) | 41 (62) |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Colorectal | — | 1 (33) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | — | 12 (33) | 21 (32) |

| KRAS wt | NA | 1 (100) | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | NA | 8 (67) | 15 (71) |

| KRAS mut | NA | — | 1 (33) | — | 1 (50) | NA | 4 (33) | 6 (29) |

| Breast (triple-negative) | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 4 (67) | — | 8 (12) |

| NSCLC | — | 1 (33) | 2 (33) | — | — | — | 9 (25) | 12 (18) |

| Head and neck | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | — | 10 (28) | 12 (18) |

| Ovarian | — | — | — | — | — | 2 (3) | — | 2 (3) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (33) | — | 1 (17) | — | — | — | 5 (14) | 7 (11) |

| Otherb | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | — | 1 (17) | — | — | — | 4 (6) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; mut, mutant; NA, not available; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; wt, wild type.

Prior cetuximab, panitumumab, erlotinib, or vendatenib therapy.

Includes esophageal and liver/biliary cancer.

Safety

In the dose-escalation cohort, grade 3 adverse events (AE) suspected to be related to MEHD7945A by the investigator (furthermore referred to as “related”) were limited to grade 3 diarrhea and nausea in 1 patient treated at the highest dose level (30 mg/kg). In the expansion cohort (14 mg/kg), no MEHD7945A-related grade ≥ 3 AEs were observed. Most common AEs occurring in ≥10% of patients are shown in Table 2. Irrespective of attribution, common AEs included headache, rash (reported as rash, dermatitis acneiform, and rash maculopapular), diarrhea, pyrexia, paronychia, chills, and dry skin. Grade ≥3 lab abnormalities were reported as an AE in less than 5% of patients.

Table 2.

MEHD7945A AEsa in ≥10% of patients and infusion-related reactions observed in ≥5% of patients

| Event term, na (%) | 1 mg/kg (n = 3) | 4 mg/kg (n = 3) | 10 mg/kg (n = 6) | 15 mg/kg (n = 6) | 22 mg/kg (n = 6) | 30 mg/kg (n = 6) | Dose expansion 14 mg/kg (n = 36) | Total MEHD7945A-related AEsb (n = 66) | Total AEs (n = 66) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | |||||||||

| Headache | — | — | 5 (83) | 6 (100) | 5 (83) | 3 (50) | 23 (64) | 37 (56) | 42 (64) |

| Rash | — | 2 (67) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 22 (61) | 34 (52) | 37 (56) |

| Diarrhea | — | 2 (67) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 19 (53) | 21 (32) | 30 (46) |

| Pyrexia | — | — | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 14 (39) | 20 (30) | 23 (35) |

| Decreased appetite | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 4 (67) | — | 13 (36) | 11 (17) | 22 (33) |

| Fatigue | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 12 (33) | 13 (20) | 22 (33) |

| Paronychia | — | 1 (33) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | — | 2 (33) | 14 (39) | 18 (27) | 20 (30) |

| Nausea | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 11 (31) | 11 (17) | 18 (27) |

| Asthenia | — | — | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 11 (31) | 7 (11) | 16 (24) |

| Chills | — | — | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 7 (19) | 16 (24) | 16 (24) |

| Vomiting | — | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | — | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 9 (25) | 9 (14) | 15 (23) |

| Dry skin | — | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 9 (25) | 14 (21) | 14 (21) |

| Cough | — | — | 1 (17) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) | — | 6 (17) | — | 12 (18) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | — | — | — | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 5 (14) | 1 (2) | 11 (17) |

| Mucosal inflammation | — | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 6 (17) | 9 (14) | 9 (14) |

| Oral pain | — | 1 (33) | 2 (33) | — | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 3 (8) | 8 (12) | 9 (14) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 4 (11) | — | 8 (12) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | — | 2 (67) | — | 2 (33) | — | — | 4 (11) | 7 (11) | 8 (12) |

| Pruritus | — | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | — | 3 (8) | 7 (11) | 8 (12) |

| Stomatitis | — | 1 (33) | — | 1 (17) | — | 3 (50) | 3 (8) | 8 (12) | 8 (12) |

| Weight decreased | — | 1 (33) | — | — | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 5 (14) | 3 (5) | 8 (12) |

| Dyspnea | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | — | — | — | 4 (11) | — | 7 (11) |

| Respiratory tract infection | — | — | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | — | — | 4 (11) | — | 7 (11) |

| Infusion-related reactionsc | |||||||||

| Headache | — | — | 5 (83) | 4 (67) | 5 (83) | 2 (33) | 22 (61) | 37 (56) | — |

| Pyrexia | — | — | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 11 (31) | 19 (29) | — |

| Chills | — | — | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 7 (19) | 16 (24) | — |

| Nausea | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 4 (11) | 7 (11) | — |

| Vomiting | — | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 4 (11) | 6 (9) | — |

| Asthenia | — | — | — | 1 (17) | — | — | 3 (8) | 4 (6) | — |

| Diarrhea | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 (11) | 4 (6) | — |

| Fatigue | — | — | — | — | — | 1 (17) | 3 (8) | 4 (6) | — |

All CTCAE v4.0 grades.

Assessed by the investigators as related. With the exception of two grade 3 events (diarrhea and nausea occurring in the same patient treated at 30 mg/kg), all other AEs were grade 1 or 2.

IRRs include any AE that was reported within 24 hours of infusion and was assessed as related to MEHD7945A. Routine premedication was recommended after the 10 mg/kg cohort.

Skin rash was mild and patients' maximum grades were mostly limited to grade 1 (56% patients) or grade 2 (11% patients) with onset mostly within the first week of administration of MEHD7945A. Overall, grade 2 rash events were seen at the 14 and 30 mg/kg doses. The majority of the nonskin events were also reported as grade 1. Results from electrocardiogram analyses did not suggest a risk of QT prolongation with MEHD7945A.

Infusion-related reactions (IRR, treatment-related AEs occurring ≤24 hours, Table 2) occurred in 48 of 66 patients (73%) treated with MEHD7945A with no IRRs reported at doses below 10 mg/kg. All IRRs were grade 1 or 2, with no discernible increase in severity with increasing dose (from 10 mg/kg to 30 mg/kg). Eighty-six percent of patients received standard premedication (mostly diphenhydramine ± acetaminophen). IRRs decreased in frequency after the first infusion (e.g., reported in 70% and 8% of patients after cycles 1 and 2, respectively), with no IRRs reported after cycle ≥ 11. Among 36 patients treated at 14 mg/kg (i.e., equivalent to the fixed phase II dose of 1,100 mg), 29 of 36 (81%) patients experienced IRRs (53% grade 1, 28% grade 2). Twenty-eight of these 29 patients (97%) had received premedication. Premedication was not mandated but recommended after observation of IRR in the 10 mg/kg dose cohort. Only 2 of the patients in the expansion phase did not receive premedication and one patient experienced grade 1 IRRs. IRRs were managed primarily and effectively with acetaminophen/paracetamol and diphenhydramine; one investigator favored prescription of opioids in 5 patients experiencing grade 2 IRRs.

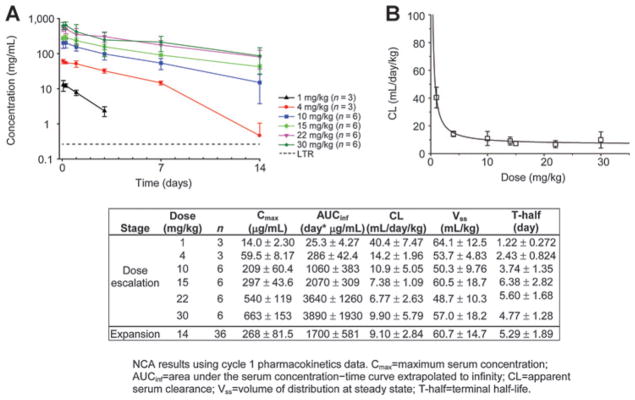

Pharmacokinetics

MEHD7945A displayed nonlinear pharmacokinetics in serum following i.v. infusions, with concentration–time profiles demonstrating a faster clearance at low dose levels (1–4 mg/kg; Fig. 2). Mean clearance of MEHD7945A decreased with increasing dose and appeared to be approaching a dose-independent mean value of 7 to 11 mL/day/kg at 10 mg/kg and above, consistent with the saturation of target-mediated drug disposition (Fig. 2). As a result, MEHD7945A exhibited pharmacokinetics that was proportional to dose where clearance was dose-independent at 10 mg/kg and above. The mean terminal T-half of MEHD7945A at 14 mg/kg in the expansion cohort was 5.3 days (range, 2.6–14 days).

Figure 2.

MEHD7945A pharmacokinetics. A, observed cycle 1 mean concentration versus nominal time. B, plot of serum clearance versus dose demonstrates that clearance is constant at doses of 10 mg/kg and higher. Consequently, receptor saturation and target-mediated elimination would be expected to reach a maximum and the phase II dose of 1,100 mg q2w (equivalent to 14 mg/kg). C, summary of noncompartmental analysis (mean ± SD).

The volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) was low (range, 49–64 mL/kg), indicating that MEHD7945A was largely confined to the vascular and interstitial spaces, which is typical for monoclonal antibodies. Additional population pharmacokinetic analysis at the end of phase I supported the use of flat dosing as currently evaluated in ongoing phase Ib and II studies (1,100 mg q2w, 1,650 mg q3w; ref. 13).

No anti-MEHD7945A antibodies were detected at any timepoint.

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamic modulation was assessed at doses ≥10 mg/kg in a total of 17 patients with colorectal cancer, NSCLC, SCCHN, ovarian, breast, and anal squamous cell carcinoma, including 11 who had previously received EGFR-targeted therapy (Table 3). Seventeen of 32 sequential biopsies obtained before and on-treatment contained sufficient tumor tissue for analysis of phosphorylation of RbS6, PRAS40, and ERK by IHC. A decrease in ≥ 1 markers was detected in 6 of 17 evaluable pairs. For the remaining 11 evaluable pairs, there was no detectable modulation in these markers. However, there was no correlation between tissue-based pharmacodynamic modulation and either dose or clinical response. Metabolic responses (≥20% decrease in FDG uptake by PET scan) were observed following doses of ≥10 mg/kg q2w in 9 of 56 (16%) patients with PET-avid disease at baseline and found to be associated with cPR by CT RECIST in 2 patients with SCCHN (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics and treatment outcomes of only those patients with signs of activity in response to MEHD7945A based on CT best response of PR or based on pharmacodynamic modulation by either tumor IHC or FDG-PET (patients with FDG-avid disease at screening only)

| Tumor type | Dose | Tumor IHC (marker reduced relative to baseline) | Best FDG-PET response (best average %SUVmax change) | Best CT response (best % change SLD) | Rash highest grade | Prior lines of treatment | Prior anti-EGFR (max duration mo) | Time on study drug (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IHC | ||||||||

| NSCLC | 10 mg/kg | pPRAS40 | SMD (12) | PD | 1 | 6 | Erlotinib (2) | 6.1 |

| CRC (Kras wt) | 10 mg/kg | pERK | SMD (−17) | PD | — | 4 | Cetuximab (6) | 6.1 |

| CRC (Kras wt) | 10 mg/kg | pPRAS40, pERK, pRbS6 | PMR (−22) | PD | 1 | 5 | Cetuximab (3) | 4.1 |

| CRC (Kras mut) | 14 mg/kg | pERK, pPRAS40, pRBS6 | SMD (0) | PD | 1 | 3 | No | 2.1 |

| CRC (Kras wt) | 14 mg/kg | pPRAS40, pERK, pRbS6 | SMD (−15) | PD | 1 | 4 | Cetuximab | 6.1 |

| CRC (Kras wt) | 15 mg/kg | pPRAS40, pERK, pRbS6 | SMD (1) | PD | 1 | 3 | Cetuximab (1) | 6.1 |

| FDG-PET | ||||||||

| CRC (Kras wt) | 14 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−23) | SD | 1 | 3 | Cetuximab (8) | 13 |

| NSCLC (EGFR wt) | 14 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−27) | NAb | — | 4 | No | 4.1 |

| NSCLCa | 14 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−25) | SD | 1 | 3 | Erlotinib (2) | 40 |

| Anal canal, SCC | 15 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−35c) | PD | 1 | 1 | No | 6.1 |

| CRC (Kras wt) | 22 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−32) | PD | — | 4 | Cetuximab (1) | 6.3 |

| Ovarian | 30 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−31) | SD | — | 5 | No | 8.3 |

| SCCHN (HPV−) | 14 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−26) | PR (−70) | 2 | 5 | Cetuximab (8) | 113.1+ |

| SCCHN (HPV−) | 14 mg/kg | n/a | PMR (−59) | PR (−70) | — | 1 | No | 50.4 |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HPV, human papillomavirus; IHC, immunohistochemistry; mut, mutant; NA, not available; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD, progressive disease; PMR, partial metabolic response; PR, partial response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SCCHN, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck; SD, stable disease; SLD, sum of longest dimension; SMD, stable metabolic disease; SMD, steady metabolic response; SUV, standardized uptake value; wt, wild type.

EGFR mutation status unknown.

CT unavailable.

Uptake time 20 minutes shorter than at screening, thus SUV percentage change may be overestimated.

CT unavailable.

Uptake time 20 minutes shorter than at screening, thus SUV percentage change may be overestimated.

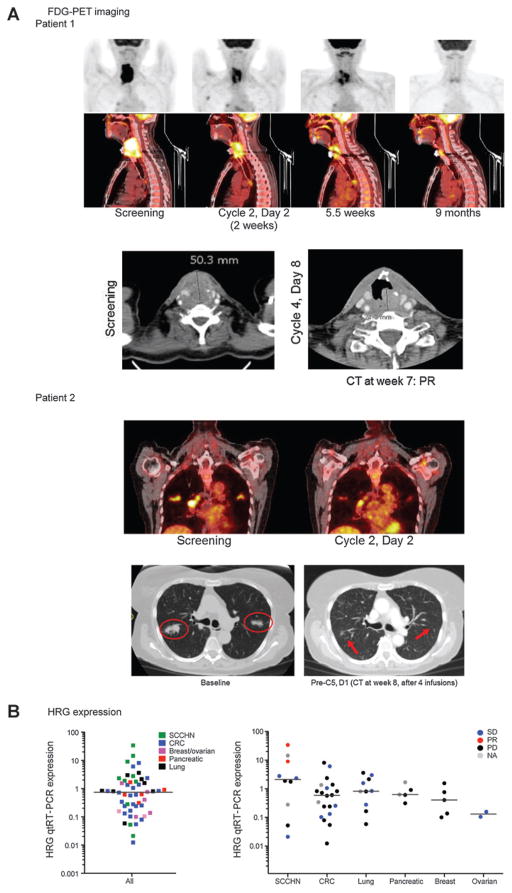

Clinical activity

Confirmed PRs were observed in 2 patients with SCCHN of the tongue and larynx with duration of PFS lasting 11.9 and 24.0+ months, respectively (Table 3; Fig. 3). Responses in both patients were associated with clinical improvement including less pain, improved phonation, and regained ability to swallow. The first patient had larynx cancer that relapsed after multiple lines of treatment, including three regimens containing cetuximab either as single agent or in combination with chemotherapy, with stable disease as a best response. The second patient had cancer of the tongue and was primarily treated with surgical excisions. Upon development of metastases to the lung, she received concurrent chemoradiation before treatment with MEHD7945A.

Figure 3.

A, marked and long-lasting tumor response by CT and FDG-PET in 2 patients with SCCHN. Patient 1 (25103) had SCCHN of the larynx, diagnosed in 2007. Prior therapies included induction chemotherapy plus chemoradiation, 3× cetuximab, plus/minus chemotherapy with a best response of stable disease. This patient showed CT PR at first tumor assessment (7 weeks) after first cycle of MEHD7945A 14 mg/kg i.v., which has been maintained to date, the patient remains on study (24.0+months duration of PFS). FDG-PET images showed pronounced reduction in FDG uptake observed at C2 and thereafter. The patient also experienced clinical improvement (less pain, improved phonation). Patient 2 (25127) had SCCHN of the tongue, diagnosed in 1994, which most recently metastasized to the lung. Prior therapies include multiple surgical resections and chemoradiation. This patient had PMR by FDG-PET and a confirmed PR after MEHD7945A at 14 mg/kg i.v. q2w and clinical improvement (regained ability to swallow). Duration of PFS was 11.9 months. B, qRT-PCR–based HRG expression levels from 52 patients with archival tissue or predose tumor samples, separated by indication and CT best response. Two patients with SCCHN had PMR by FDG-PET and confirmed PR by CT.

Tumors from both patients with PRs were human papilloma virus (HPV) negative by qRT-PCR assay for detection of E6 and E7, and expressed relatively higher levels of HRG (Fig. 3). Levels of HRG showed a broad distribution across tumor types.

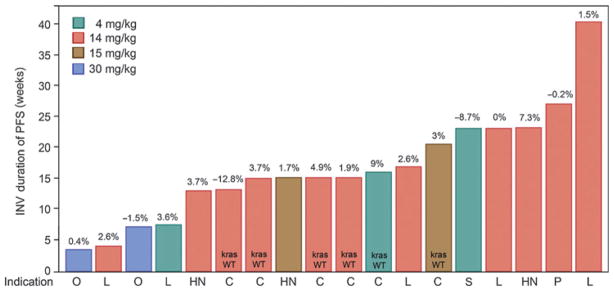

Eighteen patients experienced stable disease according to their first tumor assessment, which lasted ≥16 weeks in 8 patients with colorectal cancer (2), NSCLC (3), pancreatic cancer (1), and squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (1), and skin (ref. 1; Fig. 1). In addition, 1 patient with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) without measurable disease at baseline treated in the dose-escalation stage remained on study for ≥24 weeks without progression of pre-existing nontarget lesions.

Discussion

The anti-HER3/EGFR humanized IgG1 antibody MEHD7945A was well tolerated at a dose range up to 30 mg/kg, with no related grade ≥ 3 AEs in an expanded cohort of 36 patients receiving 14 mg/kg. Single-agent activity was observed in 2 patients with SCCHN treated in expansion stage at 14 mg/kg q2w.

The overall AE profile was largely consistent with approved monoclonal antibodies targeting EGFR with no novel safety signals. Rash was limited to grade 1 and few grade 2 events, without clear evidence of a dose–response relationship. These results are consistent with observations from nonclinical toxicology studies, where rash occurred at lower frequency and severity in cynomolgus monkeys treated with MEHD7945A compared with cetuximab. The EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibody nimotuzumab, with alternative bivalent binding and binding domain recognition, and lower binding affinity have also been suggested as possible mechanisms (15). Rash has not been identified as a toxicity associated with HER3 inhibition.

MEHD7945A demonstrated nonlinear pharmacokinetics, with faster clearance at lower doses consistent with pharmacokinetic profiles of approved EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibodies and wide expression of EGFR. However, at higher doses (≥10 mg/kg), clearance became similar (dose-independent), which is consistent with the saturation of target-clinically efficacious exposures as determined from the AUC in xenograft studies (12), and also exhibits linear clearance suggesting saturation of receptors (Fig. 2B). In addition, population pharmacokinetic analysis of the clinical data supported the use of a fixed-dose regimen by demonstrating that body weight had little influence on drug clearance, volume of distribution, and exposure, with less pharmacokinetic variability. Using the population pharmacokinetic model, 14 mg/kg was converted to an equivalent fixed dose predicted to exceed the pharmacokinetic AUC target in 90% of patients. This ultimately led to choice of RP2D of 1,100 mg q2w or 1,650 mg q3w (13).

Multiple tumor types, including colorectal cancer, NSCLC, ovarian, TNBC, and anal canal SCC, showed indirect evidence of target inhibition via pharmacodynamic modulation, by means of decreases in FDG uptake by PET scanning or decreases in phosphorylation of key signaling markers downstream from EGFR and/or HER3 as assessed by IHC in sequential tumor biopsies (although it is acknowledged that pEGFR and pHER3 would be the ideal proximate markers of intended effects, in practice neither of these assays can be reproducibly applied in a clinical setting). On-treatment pharmacodynamic analysis demonstrated targeted inhibition of EGFR and/or HER3 in a number of patients who had previously been treated with EGFR-targeted therapies. Dose-dependent changes in these pharmacodynamic assessments could not be accurately determined in large part due to the difficulty in quantitation of signals by IHC coupled with a heterogeneous staining pattern across indications and samples at baseline.

Single-agent activity was observed in 2 SCCHN patients treated at 14 mg/kg, both of which are HPV negative. Both responses were observed at the first tumor assessment after 8 weeks and were preceded by early partial metabolic responses by FDG-PET at approximately 2 weeks into treatment. Interestingly, both patients with confirmed and long-lasting PRs had tumors with high levels of HRG, and 1 patient had cetuximab-refractory disease.

These clinical findings are in line with recent studies that underscore the potential role for potent inhibition of HER3 and EGFR in SCCHN. Preclinical data show that MEHD7945A has robust antitumor activity in multiple xenograft models in which EGFR and/or HER3 signaling is important contributors to tumor growth. In an SCCHN model with high expression levels of HRG and EGFR (FaDu), the activity of MEHD7945A exceeded that of mono-specific HER family–targeting antibodies, such as cetuximab and anti-HER3 (11). Moreover, in SCCHN and NSCLC xenograft models with acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors, which were associated with enhanced activation of HER3, MEHD7945A also demonstrated substantial activity (12). A subset of SCCHN cell lines have been described that are resistant to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) exposure in vitro but are sensitive to combined EGFR/HER2 TKI inhibition in the absence of HER2 overexpression (17). Many of these cell lines were found to have high HRG expression and activation of HER3 signaling. It is hypothesized that such cells may escape the effects of EGFR inhibition via HRG-dependent signaling through an HER2/HER3 dimer. Further, analysis of >700 tumor samples from patients with SCCHN, NSCLC, colorectal cancer, breast, and ovarian cancers demonstrated that median HRG mRNA expression is significantly higher in SCCHN tumors than in the other tumor types (15) with an estimated overexpression in approximately 40% of SCCHN tumors.

Taken together, the observed responses in SCCHN tumors suggest high HRG expression to be a predictive biomarker of MEHD7495A. Dual blockade of EGFR and HER3 may enhance the targeted disruption of HER family signaling in these cancers both by blocking parallel and overlapping signaling pathways and potentially blocking the emergence of resistance. High expression of HRG could define a population of tumors that may have an oncogenic dependency on ligand-activated signaling via HER3 and may define a subpopulation of SCCHN that may be sensitive to agents targeting HER3.

In conclusion, MEHD7945A is a first-in-class dual action antibody demonstrating preliminary single-agent pharmacodynamic activity in SCCHN cancer. These results support the concept of dual EGFR and HER3 blockade in patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelial tumors in a similar fashion as previously documented in breast cancer with dual HER2 and HER3 blockade (18, 19). Ongoing studies are evaluating the clinical effectiveness of MEHD7945A in a larger phase II patient population with HER-driven cancers.

Figure 4.

Duration of PFS (weeks) as per investigator assessment for patients with stable disease at the first tumor assessment. Best percent change of sum of longest diameter (SLD) from baseline is noted on top of each bar. Indication: HN, SCCHN; L, NSCLC; P, Pancreatic; C, Colorectal; O, Ovarian; S, SCC skin. KRAS WT noted for colorectal patients only.

Translational Relevance.

This study demonstrated that the novel combination inhibitor of HER3 and EGFR could be effective in select indications, supporting continuing investigation of targeted approaches to treatment of SCCHN as single agent and colorectal cancer in combination with chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the patients and the investigators who participated in this study. They also thank Ihsan Nijem, Howard Stern, Yan Xin, Gabriele Schaefer, and Mark Sliwkowski for their scientific contributions and Rosario Roverso and Iva van den Akker for operational support. Writing assistance is provided by Genentech.

Grant Support

This work was supported by Genentech. Genentech was involved in the study design, data interpretation, and the decision to submit for publication in conjunction with the authors.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Juric D, Dienstmann R, Messersmith W, Cervantes A, Blumenschein G, Baselga J, et al. Phase I study of MEHD7945A, a first-in-class HER3/EGFR dual action antibody, in patients with locally advanced or meta-static epithelial tumors. AACR Annual Meeting, 2012.

Cervantes A, Juric D, Hidalgo M, Messersmith W, Blumenschein G, Baselga J, et al. A Phase I study of MEHD7945A, a first-in-class HER3/EGFR dual action antibody, in patients with refractory/recurrent epithelial tumors: expansion cohorts. ASCO Annual Meeting, 2012.

Hidalgo M, Calles A, Juric D, Dienstmann R, Roda D, Messersmith W, et al. Human pharmacokinetic characterization of the novel dual-action anti-HER3/EGFR antibody MEHD7945A in patients with refractory/recurrent epithelial tumors. ASCO Annual Meeting, 2012.

Juric D, Dienstmann R, Cervantes A, Messersmith W, Blumenschein G, Baselga J, et al. Pharmacodynamic assessment of drug activity in tumor tissue from patients enrolled in a Phase I study of MEHD7945A, a first-in-class HER3/EGFR dual action antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelial tumors. AACR Annual Meeting, 2013.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

W. Messersmith reports receiving a commercial research grant from Genentech/Roche. G.R. Blumenschein Jr is a consultant/advisory board member for Bayer, Biothera, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Immunogen, Novartis, and Pfizer. J. Tabernero is a consultant/advisory board member for Amgen, Genentech, Merck, Roche, and Symphogen. E. Penuel holds ownership interest (including patents) in Genentech. L.C. Amler reports receiving a commercial research grant from and holds ownership interest (including patents) in Genentech. A. Pirzkall holds ownership interest (including patents) in Genentech/Roche. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: D. Juric, R. Dienstmann, M. Hidalgo, W. Messersmith, J. Tabernero, D.S. Shames, A. Pirzkall, J. Baselga Development of methodology: R. Dienstmann, M. Hidalgo, J. Tabernero, D. Roda, X. Wang, D.S. Shames, A. Pirzkall, J. Baselga

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): D. Juric, R. Dienstmann, A. Cervantes, M. Hidalgo, W. Messersmith, G.R. Blumenschein Jr, J. Tabernero, D. Roda, A. Calles, A. Jimeno, A.V. Kapp, D.S. Shames, A. Pirzkall, J. Baselga

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): D. Juric, R. Dienstmann, M. Hidalgo, W. Messersmith, J. Tabernero, D. Roda, A. Calles, A. Jimeno, S.S. Bohórquez, C. Leddy, A.V. Kapp, D.S. Shames, E. Penuel, L.C. Amler, A. Pirzkall

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: D. Juric, R. Dienstmann, A. Cervantes, M. Hidalgo, W. Messersmith, G.R. Blumenschein Jr, J. Tabernero, D. Roda, A. Calles, A. Jimeno, C. Littman, D.S. Shames, E. Penuel, A. Pirzkall, J. Baselga

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): C. Leddy, A. Pirzkall

Study supervision: D. Juric, G.R. Blumenschein Jr, J. Tabernero, L.C. Amler, A. Pirzkall, J. Baselga

References

- 1.Sergina NV, Moasser MM. The HER family and cancer: emerging molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes NE, MacDonald G. ErbB receptors and signaling pathways in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, Levkowitz G, Alroy I, Klapper L, et al. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. EMBO J. 1996;15:2452–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbro T, Beerli RR, Maurer F, Koziczak M, Barbas CF, 3rd, Hynes NE. The ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell proliferation. PNAS. 2003;100:8933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537685100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, Blair J, Hann B, Shokat KM, et al. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature. 2007;445:437–41. doi: 10.1038/nature05474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler DL, Huang S, Kruser TJ, Nechrebecki MM, Armstrong EA, Benavente S, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to cetuximab: role of HER (ErbB) family members. Oncogene. 2008;27:3944–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand TM, Iida M, Li C. The nuclear epidermal growth factor receptor signaling network and its role in cancer. Discov Med. 2011;12:419–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RB, Gordus A, Krall JA, MacBeath G. A quantitative protein interaction network for the ErbB receptors using protein microarrays. Nature. 2006;439:168–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane RA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J. 2000;19:3159–67. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer G, Haber L, Crocker LM, Shia S, Shao L, Dowbenko D, et al. A two-in-one antibody against HER3 and EGFR has superior inhibitory activity compared with monospecific antibodies. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:472–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang S, Li C, Armstrong EA, Peet CR, Saker J, Amler LC, et al. Dual targeting of EGFR and HER3 with MEHD7945A overcomes acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors and radiation. Cancer Res. 2013;73:824–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo M, Calles A, Juric D, Dienstmann R, Roda D, Messersmith W, et al. Human pharmacokinetic characterization of the novel dual-action anti-HER3/EGFR antibody MEHD7945A in patients with refractory/recurrent epithelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl) abstr 2567. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sliwkowski MX, Schaefer G, Akita RW, Lofgren JA, Fitzpatrick VD, Nuijens A, et al. Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bebb G, Boland W, Melosky B. Don't jump to rash conclusions. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:639–41. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.7.14920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shames DS, Carbon J, Walter K, Jubb AM, Kozlowski C, Januario T, et al. High heregulin expression is associated with activated HER3 and may define an actionable biomarker in patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee-Hoeflich ST, Crocker L, Yao E, Pham T, Munroe X, Hoeflich KP, et al. A central role for HER3 in HER2-amplified breast cancer: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5878–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson TR, Lee DY, Berry L, Shames DS, Settleman J. Neuregulin-1-mediated autocrine signaling underlies sensitivity to HER2 kinase inhibitors in a subset of human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:158–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]