Abstract

PKA signaling is essential for growth and virulence of the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Little is known concerning the regulation of this pathway in filamentous fungi. Employing LC-MS/MS, we identified novel phosphorylation sites on the regulatory subunit PkaR, distinct from those previously identified in mammals and yeasts, and demonstrated the importance of two phosphorylation clusters for hyphal growth and cell wall stress response. We also identified key differences in the regulation of PKA subcellular localization in A. fumigatus compared to other species. This is the first analysis of the phosphoregulation of a PKA regulatory subunit in a filamentous fungus and uncovers critical mechanistic differences between PKA regulation in filamentous fungi compared to mammals and yeast species, suggesting divergent targeting opportunities.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, Protein kinase A, Phosphorylation, Signaling pathway regulation, Cell wall integrity, Echinocandin

INTRODUCTION

The filamentous fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus is a major infectious cause of mortality in immunocompromised patients [1–3]. In this fungus, the cAMP signaling pathway is responsible for regulating diverse processes and has been shown to be essential for virulence in an immunosuppressed murine model of invasive aspergillosis [4–6]. The master regulator of the cAMP pathway is protein kinase A (PKA), activated by release of the PKA catalytic (C) subunit from an inhibitory complex with the regulatory (R) subunit following binding of cAMP to the latter component. In contrast to the highly conserved structure of the PKA C subunit, marked diversity is observed among the R subunits of various species, allowing for refinement of regulatory function and consequent modulation of PKA activity to suit the specific requirements of different groups of organisms [7].

In mammals, multiple R subunits direct the subcellular localization of PKA in various tissues through interaction with A-kinase Anchor Proteins (AKAPs) [8]. While AKAP homologues have not been identified in fungi, PKA R subunits have been shown to control PKA localization in a number of fungal species, primarily via shuttling of the C subunit between the cytoplasm and nucleus, though the specific mechanisms are not well understood [9]. In the ascomycete model yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, localization of both the PKA C and R subunits is carbon source-dependent. In these species, both subunits are primarily observed in the nucleus during rapid log phase growth in the presence of abundant glucose, whereas glucose starvation during stationary phase growth or growth on an alternate carbon source results in migration of both subunits into the cytoplasm [10, 11]. In contrast, the PKA C subunit of the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans was found to be primarily localized to the nucleus during stationary phase growth [12], indicating differences in R subunit function even among closely related species. In all three yeasts, C subunit localization appears to be directed by the R subunit under non-cAMP-inducing conditions (i.e. low glucose), when the inactive PKA holoenzyme tetramer would be expected to assemble [10–12].

While cAMP-mediated activation of PKA occurs through a highly conserved mechanism, other more specialized avenues for regulating PKA activity have also been identified. In particular, phosphorylation of both C and R subunits is known to play an important regulatory role in a number of species. In addition to activation through conserved C subunit phosphorylation as in mammals and other fungi, we previously reported a unique mechanism of PKA inhibition in the pathogenic filamentous fungus A. fumigatus involving phosphorylation of the C subunit substrate-binding cleft [13]. We also showed that deletion of pkaC1, encoding the major PKA C subunit, resulted in hypersensitivity to the cell wall-targeting antifungal agent caspofungin, implicating a role for the PKA-signaling pathway in the cell wall-stress response. Genomic analyses undertaken to identify genes involved in caspofungin susceptibility in budding yeast have revealed the importance of the PKC-mediated cell wall integrity pathway in addition to other genes involved directly in cell wall and cell membrane biosynthesis [14]. Furthermore, PKC inhibition was found to result in increased susceptibility to cell wall inhibitors in clinical Aspergillus species isolates [14].

Regulation through R subunit phosphorylation has been primarily studied in S. cerevisiae, wherein phosphorylation of N-terminal serine clusters in this protein has been shown to mediate carbon source-dependent migration from the nucleus into the cytoplasm [15–19]. A mutant mimicking constitutive phosphorylation in these clusters displayed increased cytoplasmic localization in the presence of glucose, while a phosphorylation-deficient mutant localized to the nucleus during growth with ethanol as the sole carbon source [18]. Phosphorylation of a specific site within this N-terminal region was found to have a suppressive effect on PKA function, suggesting that this modification enhances the inhibitory capacity of the S. cerevisiae R subunit [16]. Both mammalian type II and S. cerevisiae R subunits possess an autoinhibitory PKA target site identified as phosphorylated in vivo [20–22]. Phosphorylation of this site in S. cerevisiae was shown to occur via PKA C subunit in vitro, and mutation to alanine resulted in greater binding affinity between the C and R subunits, leading to a tenfold increase in inhibition efficiency, while the phosphomimetic mutation to glutamate or aspartate resulted in reduced inhibition [20]. In vivo, phosphorylation of the autoinhibitory site was found to increase during stationary phase growth and the alanine substitution strain exhibited a markedly slower doubling time relative to the wild-type strain, as well as a transition to stationary phase at a lower optical density [20].

No experimental observations are available regarding specialized regulatory mechanisms of the PKA R subunit in filamentous fungi, including model organisms or fungal pathogens. In A. fumigatus, deletion of the single PKA R-subunit-encoding gene (pkaR) results in numerous phenotypic defects similar to those resulting from C subunit deletion, including reduced hyphal growth, decreased conidiation, and attenuated virulence [5], indicating that proper regulation of PKA activity is comparably important to A. fumigatus physiology as the presence of the kinase itself. Given this importance in virulence, we sought to delve into the specific regulatory mechanisms of A. fumigatus PKA R subunit by examining phosphoregulation of the protein under optimal growth conditions and cell wall stress conditions, as well as verify its role in localization of the PKA C subunit. We undertook a detailed functional analyses of phosphorylation sites identified via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS) and report marked variance between the phosphoregulation and function of the PKA R subunit in this filamentous fungal pathogen compared to mammalian and yeast species. These findings serve to highlight the unique nature of filamentous fungi and underscore the potential novelty associated with even highly conserved cellular pathways in this important group of organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein extraction and purification

A. fumigatus recombinant strains expressing wild-type or mutant forms of PkaR-GFP or PkaC1-GFP fusion protein were cultured in liquid glucose minimal medium (GMM) with 250 rpm shaking for 24 h at 37°C with or without 1μg/mL CSP. Total cell lysate was obtained by homogenizing mycelia (1g wet weight) using a mortar and pestle as previously described [23, 24]. Total protein in the crude extracts was quantified by the Bradford method and samples were normalized to contain 10 mg protein each. GFP-Trap® (Chromotek) affinity purifications were performed from crude extracts according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described [24].

Phosphopeptide enrichment and LC-MS/MS analysis

Phosphopeptide enrichment and LC-MS/MS were carried out as described previously [13]. Briefly, GFP-Trap® purified samples were processed for TiO2 phosphopeptide enrichment and mass spectrometry as previously described [23, 24]. Proteolytic digestion was performed by the addition of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) directly to the resin. Peptides were subjected to phosphopeptide enrichment then resuspended and subjected to chromatographic separation on a Waters NanoAquity UPLC. Samples were analyzed on a QExactive Plus mass spectrometer using a data-dependent mode of acquisition. MS/MS spectra of the 10 most abundant precursor ions were acquired with a CID energy setting of 27 and a dynamic exclusion of 20 s was employed for previously fragmented precursor ions.

Qualitative identifications and quantitative analysis of selected ion chromatograms from raw LC-MS/MS data

Raw LC-MS/MS data files were processed in Mascot distiller (Matrix Science) and then submitted to independent Mascot database searches (Matrix Science) against a custom NCBI_Aspergillus database containing both forward and reverse entries of each protein as described previously [13]. Phosphorylation site localization was assessed by exporting peak lists directly from Scaffold into the online AScore algorithm (http://ascore.med.harvard.edu/ascore.html). Peak area calculations from extracted ion chromatograms were generated within Skyline v3.5 (MacCoss Lab, University of Washington) following manual peak integration based on identification of retention time and accurate mass.

Modeling of PkaC1 three dimensional structure

The sequences of the A. fumigatus PKA catalytic subunit and PKA regulatory subunit were threaded using Coot [25] onto source models with highest sequence homologies, S. cerevisiae PKA [26] and Mus musculus PKR [27], respectively. Structural figures were rendered in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC.).

Construction of pkaR mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus

Mutant strains were generated as described previously [13]. Briefly, deletion of the gene encoding PkaR was accomplished by replacement of the pkaR coding region with a selectable pyrG marker in an akuBKU80 pyrG-auxotrophic strain (See Table S1 for all strains used) via homologous recombination. Deletion was confirmed via PCR and Southern blot. C-terminal GFP-labeling of PkaR and PkaC1 was accomplished by insertion of the appropriate coding region (lacking a stop codon) 5′ to, and in frame with, the egfp coding region within the pUCGH vector, followed by transformation into the akuBKU80 strain and screening via hygromycin B selection as described [23]. Site-directed mutagenesis of pkaR was accomplished by amplifying coding regions of the gene containing the desired point mutations via fusion PCR as described previously [13]. All mutant strains, as well as the pkaR-egfp strain expressing GFP-tagged native PkaR protein, were verified for homologous integration of mutations and egfp coding sequence at the native pkaR locus. Genomic DNAs amplified from mutant strains using a forward primer targeting a genomic DNA sequence upstream of the transformation construct and a reverse primer targeting the egfp coding region were sequenced to confirm mutations and in-frame gfp fusion. Expression of GFP-labeled PkaC1 in the pkaR deletion background was accomplished by co-transformation of an akuBKU80 pyrG-auxotrophic strain with linearized plasmids for each modification, followed my hygromycin B selection of transformants.

Determination of PKA enzyme activity

PKA activity assays were carried out as described previously [13]. Briefly, crude protein extract normalized by the Bradford method was added in duplicate for each strain to reaction mixtures containing fluorescent dye-coupled PepTag® (Promega) as a test substrate. Activity was assessed based on migration of phosphorylated peptide on an agarose gel. For quantification, gel fragments containing phosphorylated peptide were excised, melted and fluorescence readings were taken using a 540 nm excitation wavelength in a 96-well plate using a SpectraMax M3 plate reader (Molecular Devices) and compared to a standard curve. For statistical analysis, the activity of each mutant strain was compared to that of the pkaR-egfp strain via Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

Assessment of radial growth and CSP sensitivity

For radial growth assays, conidia (104) were point inoculated on solid agar media in petri plates and incubated for 5 days at 37°C, 40°C or 50°C. Media used included standard GMM (1% glucose, pH 6.5) as well as modified GMM containing 0 or 0.1% glucose, substitution of 1% sodium acetate for glucose, omission of nitrogen source sodium nitrate, substitution with alternate nitrogen source ammonium tartrate, and altered pH levels of 4.0 and 8.0. The mean radial growth rates for each of the strains were compared statistically by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). For CSP sensitivity determination, CLSI M38-A2 in vitro antifungal susceptibility standards were used [28].

Fluorescence Microscopy

Conidia (104) of GFP-labeled strains were cultured on coverslips immersed in 10 mL of liquid growth medium and incubated for 20 h at 37°C. Alternative growth media were as described above for radial growth assessment, substituting liquid for solid agar media. Hyphae were visualized using an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss) equipped with AxioVision 4.6 imaging software

RESULTS

A. fumigatus PkaR is phosphorylated at multiple sites in both caspofungin-dependent and independent manners

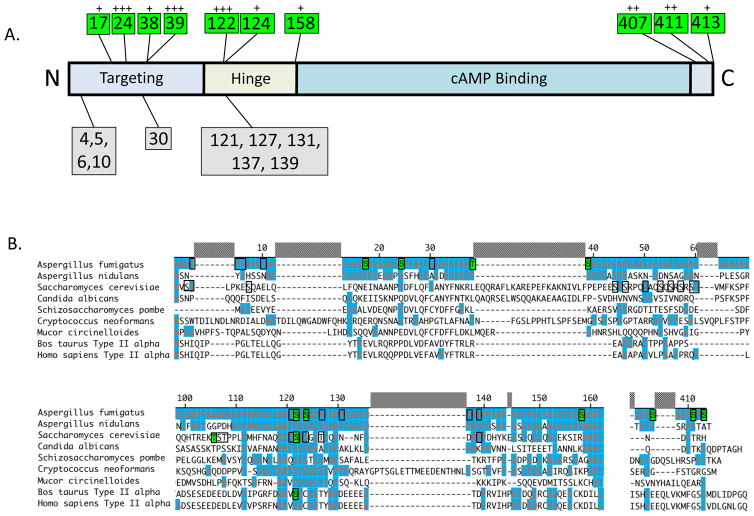

In order to assess the phosphorylation state of PkaR during growth under both optimal and cell wall stress conditions, two A. fumigatus strains expressing either C-terminally GFP-labeled PkaR (PkaR-GFP) or PkaC1 (PkaC1-GFP) fusion proteins were constructed and each cultured in the presence or absence of the anti-cell wall antifungal agent caspofungin (CSP; 1μg/mL). The GFP-labeled proteins from each strain were purified by GFP-Trap® affinity purification (Chromotek) and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. In the case of the PkaC1-GFP fusion strain, PkaR protein was indirectly isolated based on association with the labeled catalytic subunit. Thus, phosphorylation sites were identified independently for PkaR protein isolated through two distinct methods, one direct and one indirect, enhancing the robustness of the site determinations made. The majority of phosphorylated residues were identified from PkaR purified using both of these methods. The analysis led to the discovery of 20 potentially phosphorylated serine and threonine residues within the PkaR protein in total. These were clustered in three primary regions (Fig. 1A), including the less conserved amino-terminal portion associated with subcellular localization/targeting in S. cerevisiae [10], the “hinge” or autoinhibitory region homologous to the catalytic subunit binding domain of other species [7, 29], and the non-conserved extreme carboxyl terminus. Figure 1B shows amino acid sequence alignments of phosphorylated regions of A. fumigatus PkaR with other fungal and mammalian species. Of the sites identified here, S4, T121, S122, S124, S127 and T139 display identity to sites previously reported as phosphorylated in S. cerevisiae [16, 18]. However, with the exception of the S122 homologue, localization of these phosphorylation sites in the yeast species is imprecise due to the analytical methods employed. Some such studies have used gel shifts to indicate the presence or absence of phosphorylation without regard to localization [17, 21] or in conjunction with mutational analysis to identify general phosphorylated regions [18]. When more sophisticated mass spectroscopic techniques have been applied, phosphorylation data were reported without analysis of localization probabilities for specific sites [16]. Nonetheless, general phosphorylation of the N terminal and hinge regions appears conserved between the two fungal species. Only phosphorylation of the S122 homologue has previously been reported in mammalian species [21, 22].

Figure 1. Multiple sites of phosphorylation identified in PkaR by mass spectrometry.

(A) Diagram showing locations of phosphorylated sites within the PkaR protein. Residues highlighted in green were identified by LC-MS/MS as phosphorylated with greater than 50% localization probability, while residues highlighted in gray had less than 50% localization probability. (B) Clustal W alignment of phosphorylated regions of PKA regulatory subunits of selected fungal and mammalian species. Amino acids highlighted in blue indicate their conservation in relation to A. fumigatus PkaC1. Amino acids highlighted in green indicate residues that have been experimentally determined to undergo phosphorylation in the associated organism. Numbering of the residues showing the respective phosphorylation is based on the A. fumigatus protein.

Due to clustering of serine and threonine residues in these regions, precise localization of phosphorylation sites is sometimes difficult. Table 1 shows localization probability scores (Ascore) for each potential site identified. Of the 20 potential sites, only 10 had localization scores of 50 percent or higher. Sites with lower scores are likely in some cases to represent misattributions of adjacent phosphorylation sites with higher scores. For example, the phosphorylation identified at S30 with a 30.08 localization score may in fact represent misattributed phosphorylation at S24, which has a localization score of 100.00 and is also present in the peptide used to identify S30. Sites with lower localization scores frequently result from random attribution by the analysis software in cases where distinctions cannot be made between adjacent phosphorylatable residues. Sites with higher localization scores (here a score of greater than 50 is used as a cutoff as this indicates nonrandom assignation of a particular phosphorylation site) presumably represent true distinctions between sites, indicating that peptides analyzed have been fragmented adequately to isolate individual phosphorylatable residues, as illustrated in the associated spectrum plots (Fig. S1). Thus, we considered the 10 identified sites with localization scores above the cutoff value of 50 to be likely true phosphorylation sites, while those below the cutoff value were considered indeterminate. In the case of the most N terminal identified phosphorylation, no distinction could be made between sites S4, S5, S6 or T10, but it is probable that at least one of these sites was phosphorylated in the analyzed sample.

Table 1.

PkaR Phosphorylation Sites Identified by LC-MS/MS Analysis.

| Phos-phorylated Residue | Peptide Sequencea | m/z | Charge | Mass Error (ppm) | Mascot Ion Scoreb | Ascore Localization Probabilityc | Total Peptides Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S4, S5, S6, or T10 | MADSS[pS]FPGTNPFLK | 774.3443 | 0 | 2.30 | 10.3 | N/A | 1 |

| S17 | V[pS]TKDDKYSPIQK | 530.2598 | 2 | 1.97 | 22.9 | 67.89 | 2 |

| S24 | VSTKDDKY[pS]PIQK | 794.8847 | 2 | 0.20 | 68.2 | 100.00 | 101 |

| S30 | KYSPIQKI[pS]EEEEYEVT[pS]PTDPTFR | 1002.4272 | 1 | −2.28 | 19 | 30.08 | 4 |

| T38 | ISEEEEYEV[pT]SPTDPTFR | 1104.9654 | 0 | 0.73 | 39.5 | 56.11 | 8 |

| S39 | ISEEEEYEVT[pS]PTDPTFR | 1104.9645 | 0 | −0.15 | 53.9 | 87.25 | 468 |

| S121 | R[pT]SVSAESLNPTSAGSDSW[pT]PPCHPK | 977.0815 | 1 | 2.58 | 16.1 | 39.79 | 1 |

| S122 | RT[pS]VSAESLNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 950.4237 | 1 | 0.20 | 67.5 | 78.54 | 61 |

| S124 | RTSV[pS]AESLNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 713.0707 | 1 | 1.71 | 49.4 | 73.44 | 8 |

| S127 | RTSVSAE[pS]LNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK-TEEQLSR | 923.9208 | 2 | −0.84 | 21.5 | 37.04 | 8 |

| S131 | RTSVSAESLNP[pT]SAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 898.3883 | 0 | −1.68 | 25.7 | 17.48 | 2 |

| S137 | TSVSAESLNPTSAGSD[pS]WTPPCHPK | 898.3907 | 0 | 0.97 | 16.5 | 15.14 | 5 |

| S139 | R[pT]SVSAESLNPTSAGSDSW[pT]PPCHPK | 977.0815 | 1 | 2.58 | 16.1 | 38.06 | 1 |

| S158 | TAV[pS]NNFLFSHLDDDQFR | 735.9932 | 0 | 2.19 | 45.6 | 95.38 | 4 |

| S407 | RAEY[pS]AKP[pS]PS | 676.7689 | 1 | 1.68 | 29.8 | 99.31 | 12 |

| S411 | AEYSAKP[pS]PS | 558.7351 | 0 | 1.76 | 39.9 | 94.14 | 27 |

| S413 | RAEYSAKPSP[pS] | 636.7849 | 1 | 0.36 | 24.3 | 59.75 | 5 |

[pS/T] indicates phosphorylated residue

Mascot identity score of > 41 indicates identity or extensive homology (p < 0.05)

Probability of phosphorylated residue localization based on Ascore algorithm

For relative quantitative comparisons in a non-targeted LC-MS/MS based experiment, only area-under-the-curve measurements from the exact same modified peptide species (including position of phosphorylated modification within the full peptide sequence) can be directly compared across samples. This is due to the fact that peptides of different primary amino acid sequences or modification positions have different physical chemical properties and therefore ionize at different efficiencies even if they are present in equal molar quantities. Thus, statistical comparisons of phosphorylation abundance can only be made between the same phosphorylated residue across different samples in this study. However, comparison of the total numbers of peptides identified for multiple sites (that is, the number of times any peptide was identified displaying phosphorylation at each of the particular residues in question) can still help to generate hypotheses regarding relative abundance of phosphorylation at these sites. For this reason we have included these values in Table 1. This comparison suggests a relatively high degree of phosphorylation at sites S24, S39 and S122, an intermediate degree of phosphorylation at S407 and S411, and a lower degree of phosphorylation at the other sites identified. The number of peptides identified for sites closely adjacent to hypothesized highly abundant sites (e.g. T38 and S39) may be inflated due to some of these peptides representing misattribution of phosphorylation at the more abundant site.

Direct quantitative comparison of phosphorylation levels for the same site across multiple samples is possible using LC-MS/MS, so we compared abundance of phosphorylated peptides for selected sites in the presence and absence of 1 μg/mL CSP in order to identify phosphorylation events that might play a role in cell wall stress. Table 2 summarizes the results of phosphorylation level comparisons between CSP-treated and untreated samples for PkaR isolated from the PkaR-GFP and PkaC1-GFP-expressing strains. Two replicates were included for each strain type and each CSP treatment condition. Statistically significant (P < 0.05) dependence of phosphorylation on CSP exposure was identified for several sites. Phosphorylation was found to be downregulated during CSP exposure for T38 and S39, while it was upregulated during CSP exposure for S122, S124, S127, S137, T121/S139 dual phosphorylation, and S407/S411 dual phosphorylation. Upregulation was dramatic in the case of hinge region phosphopeptides (residues 121–139), ranging from 18.9 to 182.4 fold increases.

Table 2.

Caspofungin-Dependence of Phosphorylation at Selected PkaR Sites Identified by LC-MS/MS Analysis.

| Phos-phorylated Residue | Peptide Sequencea | PkaC1-GFP CSP− Peak Area | PkaC1-GFP CSP+ Peak Area | PkaC1-GFP Fold Change | PkaR-GFP CSP− Peak Area | PkaR-GFP CSP+ Peak Area | PkaR-GFP Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S17 | V[pS]TKDDKYSPIQK | 1.43e9 | 1.00e9 | −1.4 | 3.43e9 | 1.78e9 | −1.9 |

| S24 | VSTKDDKY[pS]PIQK | 1.43e9 | 9.95e8 | −1.4 | 3.45e9 | 1.80e9 | −1.9 |

| T38 | ISEEEEYEV[pT]SPTDPTFR | 3.04e10 | 254e10 | −1.2 | 5.93e10 | 2.24e10 | −2.7* |

| S39 | ISEEEEYEVT[pS]PTDPTFR | 3.04e10 | 2.54e10 | −1.2 | 5.93e10 | 2.24e10 | −2.6* |

| S121;S139 | R[pT]SVSAESLNPTSAGSDSW[pT]PPCHPK | 2.16e6 | 1.13e7 | 52.3 | 1.52e5 | 2.77e7 | 182.4* |

| S122 | RT[pS]VSAESLNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 6.39e7 | 6.31e9 | 98.7 | 5.71e8 | 1.08e10 | 18.9* |

| S124 | RTSV[pS]AESLNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 6.39e7 | 6.10e9 | 95.4 | 5.72e8 | 1.08e10 | 18.9* |

| S127 | TSVSAE[pS]LNPTSAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 3.38e7 | 4.82e8 | 14.3 | 1.46e7 | 9.16e8 | 62.9* |

| S131 | RTSVSAESLNP[pT]SAGSDSWTPPCHPK | 2.07e7 | 3.14e7 | 1.5 | 8.17e7 | 4.09e7 | −2.0 |

| S137 | TSVSAESLNPTSAGSD[pS]WTPPCHPK | 6.42e7 | 6.31e9 | 98.3 | 5.71e8 | 1.08e10 | 18.9* |

| S158 | TAV[pS]NNFLFSHLDDDQFR | 6.47e6 | 1.80e7 | 2.8 | 2.44e7 | 1.54e7 | −1.6 |

| S407;S411 | RAEY[pS]AKP[pS]PS | 4.33e8 | 6.66e8 | 1.5* | 2.20e6 | 2.32e5 | −9.5 |

| S411 | AEYSAKP[pS]PS | 1.24e9 | 1.03e9 | −1.2 | 2.12e6 | 5.79e6 | 2.7 |

| S413 | RAEYSAKPSP[pS] | 6.17e9 | 5.72e9 | −1.1 | 8.08e6 | 5.22e6 | −1.5 |

Indicates statistical significance (P<0.05).

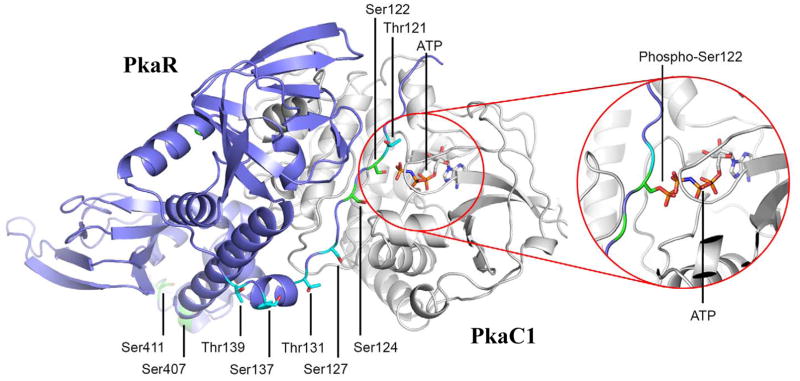

Structural modeling of A. fumigatus PkaR predicts key roles for phosphorylation in regulation of PkaC1 binding

To determine a structural role for phosphorylated residues in the PKA holoenzyme, the A. fumigatus PkaC1 and PkaR sequences were threaded onto S. cerevisiae [26] and Mus musculus source models [27], respectively, as previously reported [13] (Fig. 2). Phosphorylation of S122 was predicted to have the largest single effect on C subunit binding due to its proximity to ATP in the holoenzyme structure. According to the model, the side chain of S122 may be in favorable geometry to accommodate the gamma-phosphate of bound ATP and possibly participate in hydrogen bonding with it. Modeling a phosphoserine side chain at position 122 proved to be difficult due to steric clashes with protein in virtually every rotameric configuration; thus the phosphoserine was modeled in the singular way that it did not clash with protein. In this configuration, it clashed head-on with the gamma-phosphate of bound ATP (Fig. 2, inset). This is expected to cause strong charge repulsion between the phosphate functional groups of phosphoserine and ATP.

Figure 2. Serine and threonine residue phosphorylation in A. fumigatus PkaR.

The threaded Aspergillus fumigatus PkaR-PkaC1 model is shown with the PkaC1 polypeptide backbone in white, the PkaR backbone in violet, and the ATP cofactor in atom colors. Serine and threonine residues found to be phosphorylated with greater than 50% localization probability are highlighted in green while those with less than 50% are highlighted in cyan. The inset shows the effect of a phosphorylated Ser122 residue: massive steric clash and charge repulsion with the gamma-phosphate of bound ATP.

Other phosphorylated residues including T121 and S124 may influence holoenzyme formation and function with less impact. Specifically, T121 has its side chain oriented toward solvent in the structure, so while a phosphothreonine at position 121 would avoid steric clash, there may still be some charge repulsion with nearby ATP. S124 represented the opposite case: with a phosphoserine at position 124, significant charge repulsion would not be expected due to the distance from the ATP triphosphate moiety, however the additional electronic bulk of a phosphoserine side chain may alter the PkaC1-PkaR interface in ways that could affect function. It is notable that phosphorylation at this cluster of residues is most closely associated with the PkaC1-PkaR interface (also including S127) and is also strongly increased in response to CSP exposure (Table 2).

S24 and S39 were unfortunately not in any available structural models. They are part of the conserved regulatory subunit N-terminal dimerization domain (“D/D”) that is connected to the inhibitory polypeptide region via flexible linker ([30, 31]. Since evidence suggests the D/D interaction to be structurally symmetrical, it may be that phosphorylation of S24 and S39 could cause steric clash and/or charge repulsion with their equivalents thus disrupting the assembly of subunits in some way. The serine and threonine residues spanning positions 127–139 were not involved in either the PkaC1-PkaR holoenzyme or the quaternary tetrameric protein structure, reflecting a diminished potential role for their rates of phosphorylation. S407 and S411 were found to be phosphorylated with greater than 50% localization probability though they are not in the PkaC1-PkaR interface region. These residues are part of the C-terminal domain that is conserved and associated with cAMP binding. The extreme C-terminal portion bearing these residues is highly variable and the structural significance of phosphorylation in that region remains unclear.

Phosphorylation of PkaR contributes to hyphal growth and cell wall stress tolerance

In order to assess the functional role of phosphorylation at identified sites, site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate strains expressing mutant PkaR isoforms with non-phosphorylatable alanines substituted for selected phosphorylated residues. In the N-terminal domain, sites S24 and S39 were selected for examination due to the high number of phosphopeptides identified for these sites (Table 1), which would seem to suggest abundant phosphorylation and therefore a greater likelihood of functional significance. A strain was therefore generated expressing PkaR with alanine substitutions at these residues (PkaRS24A;S39A). In the hinge region, S122 was targeted for mutagenesis due to both the abundance of phosphopeptides identified and because the site is homologous to the conserved autoinhibitory sites of yeast and mammalian PKA regulatory subunits, in which systems its phosphorylation is of known functional importance. For this site, strains were generated expressing substitutions to both alanine (PkaRS122A) and glutamate (PkaRS122E), the latter meant to represent a constitutively phosphorylated state, as constitutive phosphorylation and dephosphorylation at this site might be expected to have unique functional consequences due to altered catalytic subunit interaction. Additionally, because both S122 and the adjacent predicted phosphorylation sites T121 and S124 were found to exhibit increased phosphorylation during CSP exposure (Table 2), a mutant strain was generated in which all three sites were mutated to alanines (PkaRT121A;S122A;S124A) to examine the possibility that tandem phosphorylation of this amino acid cluster is required to produce significant physiological effects. Finally, the S158 residue located at the junction between the hinge region and cAMP binding domains, was targeted for mutagenesis to alanine (PkaRS158A) due to the high localization probability score associated with this site and because phosphorylation has not previously been identified in homologous areas of other species studied (Fig. 1B), suggesting the potential for novel functionality. Sites within the extreme C-terminal region were not pursued for further examination in this study due to the fact that phosphorylation at these sites was not identified through analysis of directly purified GFP-labeled PkaR, but only through analysis of native PkaR indirectly purified through association with GFP-labeled PkaC1, possibly due to inhibition of phosphorylation at these sites by the presence of the C-terminal GFP label. The lack of any discernable phenotypic variation between strains expressing native PkaR versus PkaR-GFP (Fig. S2) despite the apparent absence of C terminal phosphorylation in the latter strain argues against functional significance of phosphorylation in this region. All PkaR mutant isoforms were C terminally labeled with GFP to aid in downstream analyses and comparisons were made to a strain expressing GFP-labeled native PkaR.

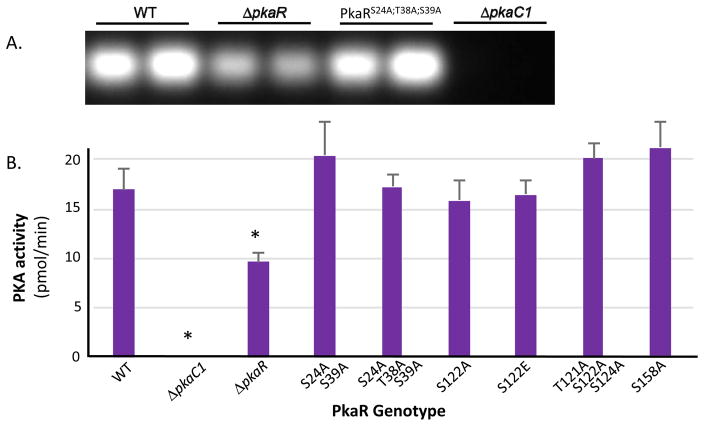

Strains expressing the described PkaR mutant isoforms were examined for altered PKA activity based on phosphorylation of a fluorescently labeled PepTag substrate peptide (Promega) added to whole cell extracts from each mutant and compared in duplicate to PkaR-GFP (WT; positive control) and PkaR deletion (ΔpkaR) strains, as well as a PkaC1 deletion strain (ΔpkaC1) [13] as a negative control. While none of the mutant strains exhibited significantly altered catalytic activity, phosphorylation of the target peptide was reduced by approximately half in the ΔpkaR strain compared to WT in a statistically significant manner (Fig. 3A, B).

Figure 3. Impact of PkaR phospho-mutations on protein kinase activity.

(A) Protein normalized crude cellular extracts for each mutant strain were added in duplicate to reaction mixtures containing fluorescent dye-coupled PepTag peptide (Promega) as a PKA-specific test substrate and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Activity was assessed qualitatively based on migration of negatively charged, phosphorylated peptide towards the anode of an agarose gel. Results shown for representative set of strains. (B) Activity was quantified by comparing fluorescence of phosphorylated substrate for each sample to a standard curve using a plate reader and the average values for each mutant were plotted. Activity was defined as pmol of substrate phosphorylated per minute. Error bars represent standard deviation. Activities were compared to the PkaR-GFP (WT) control via Student’s t-test and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by asterisks above columns. Other than the ΔpkaC1 negative control, only the ΔpkaR strain demonstrated significantly altered PKA activity.

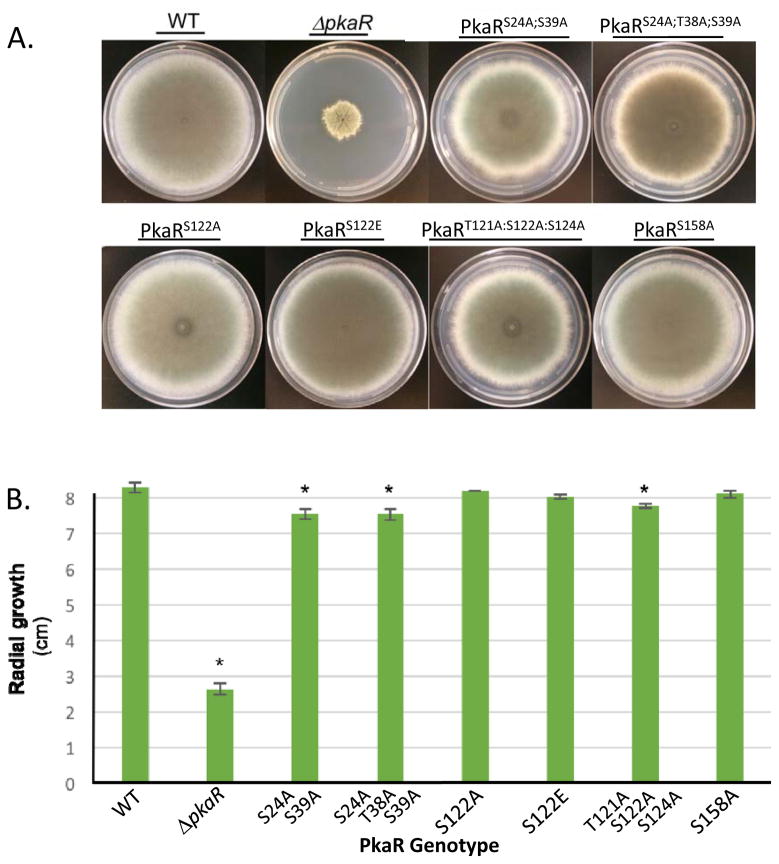

PKA activity has been previously associated with alternate carbon source utilization and heat stress tolerance in A. fumigatus [6, 13], carbon and nitrogen stress responses in S. cerevisiae [32, 33] and pH stress response in Cryptococcus neoformans [34]. To determine whether PkaR phosphorylation plays a role in hyphal growth under normal or stress-inducing conditions, the PkaR phosphorylation mutant strains were further examined for altered radial growth under optimal growth conditions on glucose minimal medium (GMM) as well as growth on the non-fermentable carbon source acetate, under carbon and nitrogen starvation conditions, heat stress, and alkaline and acidic pH stresses. Of the strains examined, the PkaRS24A;S39A, PkaRS24A;T38A;S39A and PkaRT121A;S122A;S124A mutants demonstrated slight but significant (P < 0.01) growth defects under optimal growth conditions (Fig. 4A, B) that were not exacerbated disproportionately to the control strain under any of the stress conditions tested (Fig. S3). None of the other strains exhibited significant growth defects compared to the control strain under any conditions tested, including the single alanine and glutamate substitution mutants at the S122 locus.

Figure 4. Radial growth of A. fumigatus pkaR mutants.

(A) Conidia of the indicated strains were point inoculated onto GMM agar plates and incubated for five days at 37°C. WT indicates control strain expressing GFP-tagged native PkaR (PkaR-GFP). (B) Quantitation of radial growth. Columns represent an average of three to eight replicates and error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks above columns represent statistically significant differences compared to WT as determined by Student’s t-tests (P < 0.05). Significant growth defects were identified for the DpkaR, PkaRS24A;S39A, PkaRS24A;T38A;S39A, and PkaRT121A:S122A:S124A strains.

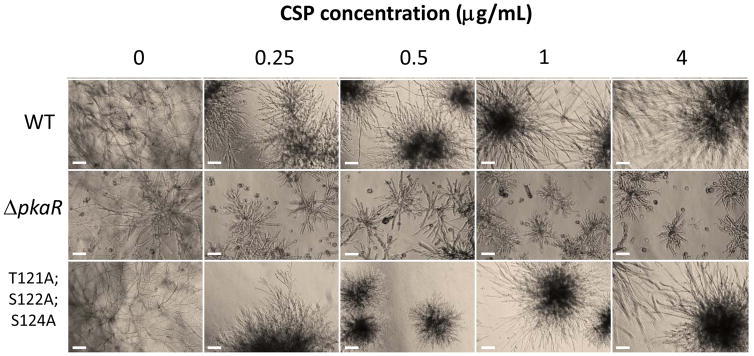

Mutants were also tested for cell wall stress tolerance by exposure to various concentrations of CSP (Fig. 5). The ΔpkaR strain showed markedly attenuated growth during exposure to CSP concentrations as low as 0.25 μg/mL compared to the control strain, and did not display paradoxical growth recovery [35] at higher concentrations, as observed in the wild-type strain at 4 μg/mL. Of the mutant strains, only the PkaRT121A;S122A;S124A strain displayed increased sensitivity to caspofungin. The growth pattern of this mutant was noticeably more aberrant than the wild-type strain at CSP 0.25 ug/mL, and hyphal elongation was markedly attenuated compared to the wild-type strain at CSP 0.5 ug/mL. While some paradoxical growth recovery was observed in this strain at higher CSP concentrations, it was less pronounced than in the wild-type strain. Although phosphorylation levels of S122 had been found to increase markedly during CSP exposure via LC-MS/MS, neither the PkaRS122A or PkaRS122E mutant strains demonstrated altered sensitivity to the compound. Thus, mutation of this site alone was insufficient to alter CSP sensitivity.

Figure 5. Caspofungin tolerance of A. fumigatus pkaR mutants.

Sensitivity of WT and PkaR mutants to caspofungin (CSP). 102 conidia were inoculated into liquid RPMI medium containing 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, or 4 μg/mL of CSP and incubated at 37°C for 48 hours. The ΔpkaR strain and a strain deficient for phosphorylation at three phosphorylated hinge region residues showed increased sensitivity to CSP compared to WT. PkaR deletion also resulted in a loss of paradoxical growth recovery at higher CSP concentrations. Scale bars represent 100 mm.

Loss of PkaR does not influence localization of PkaC1 under basal or stress-inducing growth conditions

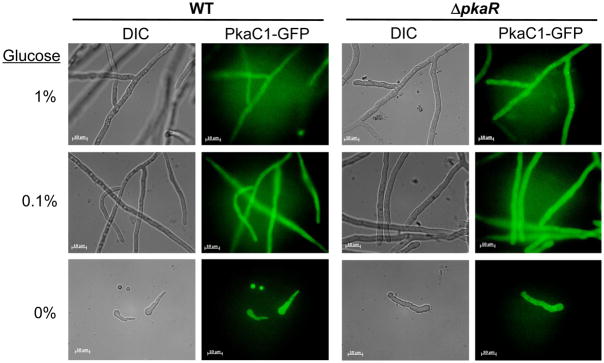

As a primary function of the PKA regulatory subunit in both mammalian and yeast species studied appears to be directing the subcellular localization of the catalytic subunit, we examined the localization patterns of GFP-labeled PkaC1 in both native (WT) and PkaR-deletion (ΔpkaR) genetic backgrounds via fluorescence microscopy grown for 24 hours under a variety of conditions including: basal (1% glucose), glucose limitation (0.1% glucose), glucose starvation (0% glucose), alternative nonfermentable carbon source (sodium acetate), alternative nitrogen source (ammonium tartrate), nitrogen starvation, pH4, and pH8. In contrast to observations reported in yeast species, we found primarily cytoplasmic localization of PkaC1 under all the conditions examined, and loss of PkaR did not have any clear impact of PkaC1 localization. Figure 6 shows representative images of PkaC1 localization in both genetic backgrounds during growth in the presence of various glucose concentrations (data not shown for alternative growth conditions).

Figure 6. Localization PkaC1 in WT and DpkaR strains.

Conidia (104) of strains expressing GFP-labeled PkaC1 (PkaC1-GFP) in wild-type (WT) and pkaR gene deletion (ΔpkaR) backgrounds were cultured on coverslips immersed in liquid broth with the indicated glucose concentrations and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Hyphae were visualized using an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss) equipped with AxioVision 4.6 imaging software. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images are shown to the left, while GFP fluorescence (PkaC1-GFP) images are shown to the right. Scale bars indicate 10 mm distances. In all instances, PkaC1 localization appeared to be primarily cytosolic.

DISCUSSION

We have defined novel mechanisms through which the PKA regulatory (R) subunit of A. fumigatus is regulated. We identified numerous novel sites of phosphorylation within this important protein, including two phosphorylation clusters with roles in regulating hyphal growth and/or the cell-wall integrity of the fungus. This is the first report identifying specific phosphorylation sites for the PKA R subunit of a filamentous fungus. For the majority of sites identified in this study, homologous sites in other species are not known to be phosphorylated, indicating the potential for both novel mechanisms of phosphorylation and unique downstream effects on PKA function. In further support of this concept, we have demonstrated that localization of the catalytic (C) subunit in this species is independent of the regulatory subunit across a range of growth conditions, in contrast to the established roles of PKA R subunits in both mammalian and yeast species.

Similarly to findings in S. cerevisiae, we identified clustered phosphorylation in the N-terminal portion of PkaR, within the less-conserved region upstream of the autoinhibitory hinge region where C subunit binding occurs. In S. cerevisiae, phosphorylation of this region has been shown to be important for the nuclear localization of the R subunit Bcy1 [18]. However, the amino acid sequence of this region in A. fumigatus PkaR bears only a low degree of similarity to the corresponding region of Bcy1, and the specific phosphorylation sites identified are not generally conserved between the two species (Fig. 1). Thus, it is plausible that phosphorylation of this domain may play a different role in A. fumigatus. We found that mutation of the two sites in this region most heavily phosphorylated based on peptide counts (S24 and S39, Table 1) resulted in slight but significant attenuation of radial growth. This appeared to be a general defect in hyphal growth and was not exacerbated disproportionately during growth under any of the environmental stresses examined. While additional mutation of T38 did not influence the phenotype further, it is possible that phosphorylation at the various identified sites within this region may function redundantly, so that mutation of a greater number of sites would be required to produce a strong phenotypic effect. In the future, it would be of interest to examine the physiological impact of truncating this region in order to better assess its importance and specific role in PKA function, as has been previously performed in budding yeast [10].

The identification of phosphorylation within this N terminal domain homologous to the targeting region of yeast raised the question of whether this phosphorylation would play a similar role in A. fumigatus. However, we were unable to identify a role for PkaR in controlling PkaC1 subcellular localization under conditions in which such a role has been previously established in S. cerevisiae, C. albicans and the fission yeast S. pombe. In these yeast species, shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm in response to environmental factors, particularly glucose abundance, appears to be an essential component of PKA function. In this study, we found that under all conditions examined PkaC1 remained primarily cytoplasmic, and that deletion of PkaR did not have a discernable effect on localization. This result is thus indicative of major discrepancy between the function of PKA R subunits in the yeasts and A. fumigatus. As the R-subunit-dependence of PKA localization has not previously been examined in a filamentous fungus, it is possible that this may represent a divergence between yeast species and filamentous fungi in general.

While phosphorylation of the highly conserved autophosphorylation site residue S122 was identified in our study, mutation of this site alone to either a non-phosphorylatable alanine or a phosphomimetic glutamate had no discernable phenotypic effects. This sharply contrasts with findings in yeast, in which the homologous site was identified as integral to regulating the stability of R and C subunit interaction and the mutation of which had pronounced physiological impact [20, 36]. In A. fumigatus, we found that mutation of additional phosphorylation sites within this hinge region was required in order to observe phenotypic alteration. These observations would also seem to be inconsistent with predictions based on our structural modeling (Fig. 2), wherein S122 phosphorylation alone was expected to strongly inhibit interaction between PkaR and ATP-bound PkaC1, which would presumably result in significant dysregulation of PKA activity and commensurate phenotypic effects in the PkaRS122E mutant strain. The phenotypic effect produced through the mutation of adjacent phosphorylation sites in addition to S122 reflects possible structural differences between A. fumigatus PkaR and/or PkaC1 in comparison to the source model structures used, resulting in altered biochemical interactions between the subunits compared to those predicted. As in the case of the N terminal region of the protein, phosphorylation of this hinge region may exhibit functional redundancy between specific sites. As in yeast, this phosphorylation may act to destabilize R and C subunit interaction. The strong increase in phosphorylation observed in this region during caspofungin exposure is of particular interest. As we found a notable increase in sensitivity to this antifungal compound in the PkaRT121A;S122A;S124A triple mutant, it would be worthwhile to determine whether mutation of the other caspofungin-dependent phosphorylation sites in this region would result in even greater sensitivity. It is possible that phosphorylation of the PkaR hinge region during caspofungin exposure may serve to enhance PKA activity to a minor degree through reduced R subunit binding, promoting tolerance to cell wall stress through undetermined mechanisms. Better understanding of the mechanisms involved in regulating this response could potentially lead to new methods for enhancing the efficacy of caspofungin and other cell-wall-targeting agents.

In order to explore possible pathways involved in PkaR phosphoregulation, we performed a bioinformatic analysis using the NetPhos 3.1 server [37] to identify potential kinases involved in phosphorylation at sites found to be involved in hyphal growth and/or caspofungin tolerance (Table 3). For the S24, T38, S39 cluster, moderate hits were produced for both MAP (p38 MAPK) and casein (CKI) kinases. The prediction of MAP kinase involvement is bolstered by the reported direct phosphorylation of the targeting region of S. cerevisae Bcy1 by MPK1[16], homologous to A. fumigatus MpkA, a key regulator of the cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway [38]. This result thus suggests potential cross talk between the cAMP and CWI pathways, or possibly involvement of the high osmolarity glycerol response pathway, regulated by the MAP kinase SakA [39, 40]. Analysis of the hinge region cluster comprising T121, S122 and S124 produced moderate hits for both calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM Kinase-II) and glycogen synthase kinase (GKS3) at all three sites (though in the case of S122 the strongest prediction was for PKA, as expected). Interestingly, in addition to CaM kinases, both the GSK3 homologue GskA and the CKI homologue CkiA have been found to play important roles in the calcium signaling pathway of Aspergillus nidulans [41]. Thus, calcium signaling might potentially be involved in regulating phosphorylation of both the hinge and targeting region clusters of PkaR. More research is needed to verify these possibilities.

Table 3.

Potential Kinases Targeting PkaR Phosphorylation Sites

| Phosphorylation Site | Kinases | NetPhos Prediction Score |

|---|---|---|

| S24 | CKI | 0.525 |

| p38 MAPK | 0.489 | |

| GSK3 | 0.483 | |

| T38 | CKI | 0.52 |

| S39 | p38 MAPK | 0.532 |

| CKI | 0.519 | |

| GSK3 | 0.495 | |

| T121 | GSK3 | 0.444 |

| CaM-II | 0.429 | |

| S122 | PKA | 0.794 |

| CaM-II | 0.494 | |

| GSK3 | 0.431 | |

| S124 | CaM-II | 0.474 |

| GSK3 | 0.441 |

This work represents the first foray into understanding the regulation of PKA R subunit function in filamentous fungi. Our findings highlight important differences between the mechanisms of PKA regulation in A. fumigatus compared to mammals and previously examined yeast species. Though R subunit phosphorylation as a means of PKA regulation is common to each group, the specific regulatory functions appear to be quite different. While this work provides new insight into PKA regulation in filamentous fungi, questions concerning the precise mechanisms through which R subunit phosphorylation impacts PKA function remain to be resolved in future studies. Though the basic PKA signaling mechanism is conserved throughout the eukarya, control of this activity through diverse R subunit isoforms represents a highly versatile component to this essential pathway and a promising focus for identifying key variations between signaling among different taxa. Elucidating the functional importance of the PKA R subunit and how its functions are specifically regulated through phosphorylation and other mechanisms in A. fumigatus will therefore represent an important step forward in our overall understanding and eventual targeting of this important human fungal pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Spectra indicating phosphorylation at specific PkaR residues. Tandem mass spectra of peptides from PkaR reveal ten unique phosphorylated serine residues. The presence of each identified C-terminal (y) and N-terminal (b) product ions are indicated within the peptide sequence. Peaks indicating phosphorylation are represented in yellow.

Figure S2. Radial growth of A. fumigatus pkaR-GFP and PkaR mutant strains. (A) Comparison of hyphal growth in strains expressing native or GFP-tagged PkaR. Conidia of the pkaR-egfp strain (expressing C-terminally GFP-tagged PkaR, PkaR-GFP) and its parent strain akuBKU80 were point inoculated onto GMM agar plates and incubated for five days at 37°C in triplicate. No significant differences in radial growth rate were measured between the two strains. Representative plates are shown. (B) Quantitation of radial growth of selected PkaR mutants under stress conditions. Conidia of the indicated strains were point inoculated onto agar plates and incubated for five days. “Standard” refers to growth at 37 C on GMM (pH 6.5). The “40 C” and “50 C” groups were grown on GMM at those temperatures. For the “pH 4” and “pH 8” groups, GMM was adjusted to the indicated pHs. For the “Acetate” group, sodium acetate (1%) was substituted for glucose in the medium. Columns represent an average of 8 replicates for standard conditions and 3 replicates for all other conditions. Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks above columns represent statistically significant differences in comparison to the WT (PkaR-GFP) control as determined by Student’s t-tests (P < 0.05). For the stress conditions depicted here and others not shown but referenced in the text, only the DpkaR strain showed significantly altered growth in comparison to the WT control.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING INFORMATION

These studies were supported by the Tri-Institutional Molecular Mycology and Pathogenesis Training Program (2T32 AI052080-11) post-doctoral fellowship to EKS and NIH/NIAID multi-PI R01 award AI112595 to WJS.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PKA

protein kinase A

- CSP

caspofungin

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy

References

- 1.Pagano L, Caira M, Candoni A, Offidani M, Fianchi L, Martino B, Pastore D, Picardi M, Bonini A, Chierichini A, Fanci R, Caramatti C, Invernizzi R, Mattei D, Mitra ME, Melillo L, Aversa F, Van Lint MT, Falcucci P, Valentini CG, Girmenia C, Nosari A. The epidemiology of fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: the SEIFEM-2004 study. Haematologica. 2006;91:1068–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, Pfaller M, Chang C, Webster K, Marr K. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:265–273. doi: 10.1086/595846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, Ito J, Andes DR, Baddley JW, Brown JM, Brumble LM, Freifeld AG, Hadley S, Herwaldt LA, Kauffman CA, Knapp K, Lyon GM, Morrison VA, Papanicolaou G, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Schuster MG, Walker R, Wannemuehler KA, Wingard JR, Chiller TM, Pappas PG. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001–2006: Overview of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Database. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 SRC - GoogleScholar:1091–1100. doi: 10.1086/651263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leibmann B, Müller M, Braun A, Brakhage A. The cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase a network regulates development and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5193–5203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5193-5203.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao W, Panepinto JC, Fortwendel JR, Fox L, Oliver BG, Askew DS, Rhodes JC. Deletion of the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A in Aspergillus fumigatus alters morphology, sensitivity to oxidative damage, and virulence. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4865–4874. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00565-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller KK, Richie DL, Feng X, Krishnan K, Stephens TJ, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Askew DS, Rhodes JC, Kinase A. Divergent Protein isoforms co-ordinately regulate conidial germination, carbohydrate metabolism and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1045–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canaves J, Taylor S. Classification and phylogenetic analysis of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit family. J Mol Evol. 2002;54:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colledge M, Scott J. AKAPs: from structure to function. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:216–221. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffioen G, Thevelein J. Molecular mechanisms controlling the localisation of protein kinase A. Curr Genet. 2002;41:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s00294-002-0308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffioen G, Anghileri P, Imre E, Baroni MD, Ruis H. Nutritional control of nucleocytoplasmic localization of cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic and regulatory subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275 SRC - GoogleScholar:1449–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo Y, McInnis B, Marcus S. Regulation of the subcellular localization of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in response to physiological stresses and sexual differentiation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1450–1459. doi: 10.1128/EC.00168-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassola A, Parrot M, Silberstein S, Magee BB, Passeron S, Giasson L, Cantore ML. Candida albicans lacking the gene encoding the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A displays a defect in hyphal formation and an altered localization of the catalytic subunit. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3 SRC - GoogleScholar:190–199. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.190-199.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shwab EK, Juvvadi PR, Waitt G, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, Nicely NI, Asfaw YG, Steinbach WJ. A Novel Phosphoregulatory Switch Controls the Activity and Function of the Major Catalytic Subunit of Protein Kinase A in Aspergillus fumigatus. MBio. 2017;8:e02319–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02319-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markovich S, Yekutiel A, Shalit I, Shadkchan Y, Osherov N. Genomic approach to identification of mutations affecting caspofungin susceptibility in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3871–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3871-3876.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffioen G, Swinnen S, Thevelein JM. Feedback inhibition on cell wall integrity signaling by Zds1 involves Gsk3 phosphorylation of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit. J Biol Chem. 2003;278 SRC - GoogleScholar:23460–23471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210691200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soulard A, Cremonesi A, Moes S, Schütz F, Jenö P, Hall MN. The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3475–3486. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budhwar R, Lu A, Hirsch JP. Nutrient control of yeast PKA activity involves opposing effects on phosphorylation of the Bcy1 regulatory subunit. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21 SRC - GoogleScholar:3749–3758. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffioen G, Branduardi P, Ballarini A, Anghileri P, Norbeck J, Baroni M, Ruis H. Nucleocytoplasmic distribution of budding yeast protein kinase A regulatory subunit Bcy1 requires Zds1 and is regulated by Yak1-dependent phosphorylation of its targeting domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:511–23. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.511-523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budhwar R, Fang G, Hirsch J. Kelch repeat proteins control yeast PKA activity in response to nutrient availability. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:767–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.5.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuret J, Johnson KE, Nicolette C, Zoller M. Mutagenesis of the regulatory subunit of yeast cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Isolation of site-directed mutants with altered binding affinity for catalytic subunit. J Biol Chem. 1988;5:9149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner-Washburne M, Brown D, Braun E. Bcy1, the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in yeast, is differentially modified in response to the physiological status of the cell. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19704–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rangel-Aldao R, Rosen O. Dissociation and reassociation of the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from bovine cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:3375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juvvadi PR, Belina D, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, Steinbach WJ. Filamentous fungal-specific septin AspE is phosphorylated in vivo and interacts with actin, tubulin and other septins in the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2013;431 SRC - GoogleScholar:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juvvadi PR, Ma Y, Richards AD, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, Lamoth F, Steinbach WJ. Identification and mutational analyses of phosphorylation sites of the calcineurin-binding protein CbpA and the identification of domains required for calcineurin binding in Aspergillus fumigatus. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:175. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan KD. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr Crystallogr. 2010;66 SRC - GoogleScholar:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng J, Trafny EA, Knighton DR, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Ten Eyck LF, Sowadski JM. A refined crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with MnATP and a peptide inhibitor. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1993;49 SRC - GoogleScholar:362–365. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Cheng CY, Saldanha SA, Taylor SS. PKA-I holoenzyme structure reveals a mechanism for cAMP-dependent activation. Cell. 2007;130:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute, C. a. L. S. CLSI document M38-A2. 2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinaldi J, Wu J, Yang J, Ralston CY, Sankaran B, Moreno SSST. Structure of yeast regulatory subunit: a glimpse into the evolution of PKA signaling. Structure. 2010;18:1471–82. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor SS, Ilouz R, Zhang P, Kornev AP. Assembly of allosteric macromolecular switches: lessons from PKA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:646–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González Bardeci N, Caramelo JJ, Blumenthal DK, Rinaldi J, Rossi S, Moreno S. The PKA regulatory subunit from yeast forms a homotetramer: Low-resolution structure of the N-terminal oligomerization domain. J Struct Biol. 2016;193:141–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan X, Heitman J. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4874–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamaki H. Glucose-stimulated cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;104:245–50. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Meara TR, Norton D, Price MS, Hay C, Clements MF, Nichols CB, Alspaugh JA. Interaction of Cryptococcus neoformans Rim101 and protein kinase A regulates capsule. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000776. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiederhold NP. Attenuation of echinocandin activity at elevated concentrations: a review of the paradoxical effect. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:574–578. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f1be7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin LR, Kuret J, Johnson KE, Powers S, Cameron S, Michaeli T, Wigler M, Zoller MJ. A mutation in the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase that disrupts regulation. Science. 1988;240:68–70. doi: 10.1126/science.2832943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blom N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004;4:1633–49. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain R, Valiante V, Remme N, Docimo T, Heinekamp T, Hertweck C, Gershenzon J, Haas H, Brakhage AA. The MAP kinase MpkA controls cell wall integrity, oxidative stress response, gliotoxin production and iron adaptation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du C, Sarfati J, Latge J, Calderone R. The role of the sakA (Hog1) and tcsB (sln1) genes in the oxidant adaptation of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2006;44:211–8. doi: 10.1080/13693780500338886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma D, Li R. Current understanding of HOG-MAPK pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycopathologia. 2013;175:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernández-Ortiz P, Espeso EA. Phospho-regulation and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of CrzA in response to calcium and alkaline-pH stress in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:532–51. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Spectra indicating phosphorylation at specific PkaR residues. Tandem mass spectra of peptides from PkaR reveal ten unique phosphorylated serine residues. The presence of each identified C-terminal (y) and N-terminal (b) product ions are indicated within the peptide sequence. Peaks indicating phosphorylation are represented in yellow.

Figure S2. Radial growth of A. fumigatus pkaR-GFP and PkaR mutant strains. (A) Comparison of hyphal growth in strains expressing native or GFP-tagged PkaR. Conidia of the pkaR-egfp strain (expressing C-terminally GFP-tagged PkaR, PkaR-GFP) and its parent strain akuBKU80 were point inoculated onto GMM agar plates and incubated for five days at 37°C in triplicate. No significant differences in radial growth rate were measured between the two strains. Representative plates are shown. (B) Quantitation of radial growth of selected PkaR mutants under stress conditions. Conidia of the indicated strains were point inoculated onto agar plates and incubated for five days. “Standard” refers to growth at 37 C on GMM (pH 6.5). The “40 C” and “50 C” groups were grown on GMM at those temperatures. For the “pH 4” and “pH 8” groups, GMM was adjusted to the indicated pHs. For the “Acetate” group, sodium acetate (1%) was substituted for glucose in the medium. Columns represent an average of 8 replicates for standard conditions and 3 replicates for all other conditions. Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks above columns represent statistically significant differences in comparison to the WT (PkaR-GFP) control as determined by Student’s t-tests (P < 0.05). For the stress conditions depicted here and others not shown but referenced in the text, only the DpkaR strain showed significantly altered growth in comparison to the WT control.