Abstract

Adverse perinatal health outcomes are heightened among women with psychosocial risk factors, including childhood adversity and a lack of social support. Biological aging could be one pathway by which such outcomes occur. However, data examining links between psychosocial factors and indicators of biological aging among perinatal women are limited. The current study examined the associations of childhood socioeconomic status (SES), childhood trauma, and current social support with telomere length in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in a sample of 81 women assessed in early, mid, and late pregnancy as well as 7–11 weeks postpartum. Childhood SES was defined as perceived childhood social class and parental educational attainment. Measures included the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and average telomere length in PBMCs. Per a linear mixed model, telomere length did not change across pregnancy and postpartum visits; thus, subsequent analyses defined telomere length as the average across all available timepoints. ANCOVAs showed group differences by perceived childhood social class, maternal and paternal educational attainment, and current family social support, with lower values corresponding with shorter telomeres, after adjustment for possible confounds. No effects of childhood trauma or social support from significant others or friends on telomere length were observed. Findings demonstrate that while current SES was not related to telomeres, low childhood SES, independent of current SES, and low family social support were distinct risk factors for cellular aging in women. These data have relevance for understanding potential mechanisms by which early life deprivation of socioeconomic and relationship resources affect maternal health. In turn, this has potential significance for intergenerational transmission of telomere length. The predictive value of markers of biological versus chronological age on birth outcomes warrants investigation.

Keywords: childhood SES, childhood trauma, social support, telomeres, pregnancy

1. Introduction

Risk for pregnancy complications (e.g., preeclampsia) and adverse birth outcomes (e.g., preterm birth, low birth weight) are enhanced among women with psychosocial risk factors, including low socioeconomic status, history of childhood trauma, and a lack of social support (e.g., Blumenshine et al., 2010; Dunkel Schetter, 2011). For example, among pregnant women, each adverse childhood experience has been associated with a 16.33g reduction in infant birth weight and a 0.063 week decrease in gestational age at delivery (Smith et al., 2016). In addition, evidence has shown that social support may have direct and/or indirect effects on perinatal outcomes, such as birth weight, small for gestational age, and postpartum depression, (Dunkel Schetter, 2011; Yim et al., 2015). Although data have indicated that poorer health behaviors, such as cigarette use, play a role in the association between psychosocial stress and perinatal health outcomes (e.g., Lobel et al., 2008), they do not fully account for these effects. The role of biological pathways requires explication.

In relation to biology, indicators of aging may be of particular relevance for women of childbearing age. Advancing maternal age is a strong predictor of risk for adverse perinatal health outcomes; these risks are observed as early as age 30 but advance considerably at 35 years (e.g., Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2015). Of importance, individuals of similar chronological age can vary considerably in indicators of aging at the cellular level (Müezzinler et al., 2013). Thus, it is plausible that psychosocial factors may increase risk for adverse perinatal health outcomes in part by promoting biological aging.

Telomere length is a key indicator of biological aging. Defined as DNA-protein complexes found at the end of chromosomes, telomeres play a crucial role in the protection of genetic stability (Blackburn, 2005). Telomere length shortens with each replication of the cell, and is further reduced by oxidative stress. When telomeres shorten to a critical length, genomic instability ensues, cellular replication ceases, and cell senescence occurs (von Zglinicki, 2002). As a sensitive indicator of cellular aging, shorter telomere length has been linked with various health outcomes, such as myocardial infarctions, strokes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (D’Mello et al., 2015).

Importantly, a growing literature links psychosocial exposures with telomere length. For example, a lack of social support has been associated with shorter telomeres in non-pregnant adults (Barger and Cribbet, 2016; Carroll et al., 2013; Uchino et al., 2012). However, effects of unique sources of social support remain to be elucidated. In addition, experiences of childhood trauma have been associated with shorter telomeres in adulthood in multiple studies (for metaanalyses, see Hanssen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017). Given the large literature on early childhood maltreatment and telomere length, data on effects of childhood socioeconomic disadvantage are notably lacking. In addition, studies examining psychosocial factors and telomere length have largely focused on older adults (Schutte and Malouff, 2015; Starkweather et al., 2014), with less data specific to women of childbearing age.

Finally, pregnancy is a time of considerable physiological changes including marked increases in serum and salivary cortisol, serum proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), and ex vivo LPS-stimulated proinflammatory cytokine production (e.g., Christian and Porter, 2014; Gillespie et al., 2016). Notably, elevations in cortisol and serum inflammatory markers have been linked with telomere shortening in non-pregnant adults (Révész et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2014). Given that these inflammatory and neuroendocrine adaptations represent typical pregnancy-related physiology (e.g., Christian and Porter, 2014; Glynn et al., 2007) and are important for critical processes in pregnancy, such as parturition (McLean et al., 1995; Mor et al., 2011), it is unknown if similar effects on telomere biology occur in context of pregnancy.

To address gaps in the literature, the current study examined the associations of childhood socioeconomic status, childhood trauma, and current social support with telomere length in PBMCs in a racially diverse sample of 81 pregnant women who were assessed during each trimester of pregnancy and at 7–11 weeks postpartum. In the current study, it was hypothesized that a) lower childhood socioeconomic status (per perceived childhood social class and parental educational attainment), b) exposure to childhood trauma (per self-reported abuse and neglect) and c) lower perceived social support would be associated with shorter telomere length of PBMCs. The predictive value of perceived support from different sources (friends, family, significant other) was determined. Finally, stability in telomere length across the course of pregnancy and postpartum visits was examined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

This study included 84 women recruited from the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC) Prenatal Clinic and the community of Columbus, Ohio. Data collection occurred from 2011 to 2014. Blood samples and psychosocial data were collected in early, mid, and late pregnancy as well as 7–11 weeks postpartum. The broader study consisted of 144 women with data collected from 2009 to 2011; blood for telomere assays was only available for women from the second wave of the study (n = 84). Exclusion criteria included multi-fetal gestation, known fetal anomaly, medications or health conditions with a major immunological or endocrine component (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism). No women self-reported alcohol consumption after pregnancy was known. Women who used illicit drug use other than marijuana during or in the six months prior to the current pregnancy were excluded. The current analyses included women who participated in at least two study visits; two women were excluded because they did not meet these criteria. Fourteen women were missing data on childhood SES (n = 1, maternal education level; n = 13, paternal education level) and five were missing data on childhood trauma; thus, these women were excluded from respective analyses. Written informed consent was obtained at the first study visit, and participants received modest financial compensation at the completion of each study visit, for a total of $230 if all study visits were completed. The study was approved by the OSU Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographics

Race/ethnicity, age, marital status, annual household income, education level, and number of prior births (parity) were collected by self-report at the first study visit. Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) was calculated utilizing self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and measured height at the first visit. Pregnancy complications (i.e., gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes) were obtained per medical record review.

2.2.2 Health behaviors

At the first study visit, smoking status and exercise were assessed via self-report. Smoking was categorized as current or not current. In terms of exercise, participants responded to an item assessing the frequency with which they engaged in vigorous activity long enough to build up a sweat: less than once per month, once per month, 2–3 times per month, once per week, or more than once per week. Prenatal vitamin use was defined as never, 1–3 days/week, 4–6 days/week, or 7 days/week.

2.2.3 Childhood socioeconomic status (SES) indicators

Childhood SES was assessed at the first study visit using three different indicators: perceived childhood social class, maternal educational attainment, and paternal educational attainment. Women responded to perceived childhood social class on a 5-point scale: lower class, working class, lower middle class, upper middle class, and higher class. Maternal and paternal educational attainment were categorized as less than high school, high school graduate/some college, or college graduate, based on participant report.

2.2.4 Childhood trauma

The 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) is comprised of 5 subscales: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect (Bernstein et al., 2003). Each item is responded to on a 5-point scale, from “Never true” to “Very often true.” This scale has shown good criterion, convergent, and discriminant validity in adults (Bernstein et al., 2003). The CTQ was administered at the third study visit to reduce respondent burden in earlier visits and increase opportunities to build rapport with participants. In the current study, women were categorized on each subscale as reporting prior abuse or neglect below versus above the clinical cutoff. The clinical cutoff was defined using the moderate to severe cutoff on each CTQ subscale (emotional abuse > 13, physical abuse > 10, sexual abuse > 8, emotional neglect > 15, physical neglect > 10); these cutoffs have been used in prior studies (e.g., Heim et al., 2009). Total trauma exposure was defined as the number of times above the moderate to severe cutoff across all subscales: none, one type of trauma, two or more types of trauma.

2.2.5 Depressive symptoms

Given the evidence supporting a link between depression and telomere length (e.g., Schutte and Malouff, 2015), childhood SES and social support indicators were examined as predictors of telomere length independent of depressive symptoms at the first study visit. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item measure of cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, and somatic depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is predictive of physiological processes as well as perinatal health outcomes (e.g., Christian et al., 2009).

2.2.6 Social support

Perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others was assessed using the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) at the first study visit (Zimet et al., 1988). This scale has shown good construct validity and reliability with pregnant women (Zimet et al., 1990). The three-factor structure of the scale (family, friends, and significant others) has been supported in a sample of pregnant women (Zimet et al., 1990); thus, these subscales were examined as separate total scores. Regarding the significant other subscale, directions on the original MSPSS ask the participant to reflect on a “special person” for these items. Data have shown that adults aged 18 to 77 often consider other family members, children, or friends in addition to romantic partners as a “special person” (Prezza and Giuseppina Pacilli, 2002). Thus, consistent with other studies, we adapted the wording on the significant other subscale items to “a special person (husband, boyfriend, or other romantic partner)” to specifically capture perceived support from this source.

2.2.7 Telomere measurement

Blood was collected in vacutainer tubes while participants were in a seated position. Total genomic DNA was purified from whole blood using QIAamp® DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN, Cat#51104) and stored at −80°C for batch telomere length measurement. DNA quantity and quality was assessed using 260/280 UV spectrophotometery and Picogreen Assay. The telomere length measurement assay is adapted from the method originally published by Cawthon (Cawthon, 2002). The telomere thermal cycling profile consists of: Cycling for T(telomic) PCR: Denature at 96°C for 1 minute, one cycle; denature at 96°C for 1 second, anneal/extend at 54°C for 60 seconds, with fluorescence data collection, 30 cycles. Cycling for S (single copy gene) PCR: Denature at 96°C for 1 minute, one cycle; denature at 95°C for 15 seconds, anneal at 58°C for 1 second, extend at 72°C for 20 seconds, 8 cycles; followed by denature at 96°C for 1 second, anneal at 58°C for 1 second, extend at 72°C for 20 seconds, hold at 83°C for 5 seconds with data collection, 35 cycles.

The primers for the telomere PCR are tel1b [5'-CGGTTT(GTTTGG)5GTT-3'], used at a final concentration of 100 nM, and tel2b [5'-GGCTTG(CCTTAC)5CCT-3'], used at a final concentration of 900 nM. The primers for the single-copy gene (human beta-globin) PCR are hbg1 [5' GCTTCTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC-3'], used at a final concentration of 300 nM, and hbg2 [5';-CACCAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3'], used at a final concentration of 700 nM. The final reaction mix contains 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4; 50 mM KCl; 200 µM each dNTP; 1% DMSO; 0.4× Syber Green I; 22 ng E. coli DNA ; 0.4 Units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Inc.) 10 ng of genomic DNA per 11 µl reaction. Tubes containing 26, 8.75, 2.9, 0.97, 0.324 and 0.108 ng of a reference DNA (from Hela cancer cells) are included in each PCR run so that the quantity of targeted templates in each research sample can be determined relative to the reference DNA sample by the standard curve method. The same reference DNA was used for all PCR runs.

To control for inter-assay variability, 8 control DNA samples are included in each run. In each batch, the T/S ratio of each control DNA is divided by the average T/S for the same DNA from 10 runs to get a normalizing factor. This is done for all 8 samples and the average normalizing factor for all 8 samples is used to correct the participant DNA samples to get the final T/S ratio. The T/S ratio for each sample was measured twice. When the duplicate T/S value and the initial value vary by more than 7%, the sample was run the third time and the two closest values were reported. All timepoints for the same participant were run in the same assay plate to rule out potential plate-to-plate batch variation. The CV for this study is 2.9%. Lab personnel who performed the assays were blind to all demographic and clinical data.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in SPSS 24.0. Three outlier data points, as defined by the a priori chosen cut-off of ± 3 SD from the mean, were excluded from analyses (telomere length = 2; depressive symptoms = 1). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all participants. To examine whether telomere length changed across pregnancy and postpartum visits, a linear mixed model was conducted. A subject-level random effect was included in this model to account for dependency between repeated measures; restricted maximum likelihood estimation was utilized to address missing data. Next, group differences on telomere length among childhood SES indicators, exposure to childhood trauma, and current social support were examined using analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs). Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) was used for post-hoc tests.

All models with covariates adjusted for age, race, current income, education level, marital status, BMI, exercise, smoking status, and depressive symptoms based on findings in the literature (Starkweather et al., 2014). A mean value for telomere length across pregnancy and postpartum was determined and served as the outcome variable. In this sample, 14 women could not recall their mother’s (n = 1) or father’s (n = 13) education level, and 5 women did not participate in the study visit when childhood trauma was assessed; thus, these women were excluded from the respective analyses, resulting in final analytic samples of 81, 80, 68, and 76 for self-reported childhood social class (per 5-point rating scale), maternal education level, paternal education level, and childhood trauma exposure, respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Demographic characteristics, health behaviors, and childhood SES indicators distributions are detailed in Tables 1 & 2. Study visits occurred during early (12.41 ± 1.59 weeks), mid (20.64 ± 1.29 weeks), and late pregnancy (29.23 ± 1.41 weeks), as well as 7–11 weeks postpartum (8.86 ± 0.82 weeks). The average maternal age was 25.48 years (SD = 4.27; range = 18–33), 52% were White (n = 42), 42% were married (n = 34), and 53% reported an annual household income of less than $30,000 (n = 43). In this sample, no women reported alcohol use after pregnancy was known and two women reported marijuana use.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (n = 81)

| Age [Mean (SD)] | 25.5 (4.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 42 (51.9) |

| Black/African American | 39 (48.1) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 34 (42.0) |

| In a relationship | 37 (45.7) |

| Single | 10 (12.3) |

| Current Education | |

| Less than High School | 7 (8.6) |

| High School Graduate | 16 (19.8) |

| Some College | 30 (37.0) |

| College Degree | 28 (34.6) |

| Income | |

| <$15,000 | 25 (30.9) |

| $15,000-$29,999 | 24 (29.6) |

| $30,000-$49,999 | 14 (17.3) |

| >$50,000 | 18 (22.2) |

| Parity (# of prev. births) | |

| 0 | 27 (33.3) |

| 1 | 28 (34.6) |

| 2 or more | 26 (32.1) |

| Smoking Status | |

| No current use | 72 (88.9) |

| Current use | 9 (11.1) |

| Exercise | |

| Less than once per month | 21 (25.9) |

| Once per month | 10 (12.3) |

| 2–3 times per month | 21 (25.9) |

| Once per week | 13 (16.0) |

| More than once per week | 16 (19.8) |

| Prenatal Vitamin Use | |

| Never | 6 (7.4) |

| 1–3 days/week | 10 (12.3) |

| 4–6 days/week | 15 (18.5) |

| 7 days/week | 50 (61.7) |

| BMI [Mean (SD)] | 27.3 (6.2) |

| CES-D [Mean (SD)] | 14.7 (9.8) |

| Pregnancy Complications | 5 (6.2) |

Note. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale.

Pregnancy complications defined as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or gestational diabetes. n(%) unless otherwise noted

Table 2.

Childhood Socioeconomic Status Indicators and Trauma Exposure Subscales

| [n (%)] | |

|---|---|

| Perceived Childhood Social Class (n = 81) | |

| Lower/Working Class | 31 (38.3) |

| Lower Middle Class | 31 (38.3) |

| Upper Middle Class | 19 (23.5) |

| Higher Class | 0 (0.0) |

| Maternal Educational Attainment (n = 80) | |

| Less than High School | 16 (20.0) |

| High School Graduate, Some College | 41 (51.3) |

| College Degree | 23 (28.8) |

| Paternal Educational Attainment (n = 68) | |

| Less than High School | 14 (20.6) |

| High School Graduate, Some College | 32 (47.1) |

| College Degree | 22 (32.4) |

| Trauma Exposure (n = 76) | |

| Emotional Abuse | 10 (13.2) |

| Physical Abuse | 5 (6.2) |

| Sexual Abuse | 15 (19.7) |

| Emotional Neglect | 9 (11.8) |

| Physical Neglect | 12 (15.8) |

| Total Trauma Exposure | |

| None | 50 (65.8) |

| One | 12 (15.6) |

| Two or more | 14 (18.1) |

Note. Values represented as n (%). Frequencies associated with abuse and neglect subscales depict the number of women above the clinical cutoff. Total trauma exposure was defined as the number of times above the moderate to severe cutoff across all subscales.

3.2 Telomere length stability across pregnancy and postpartum

Means and standard deviations for telomere length at each respective visit are described in Table 3. A linear mixed model was conducted to examine changes in telomere length across pregnancy and postpartum visits. No significant effect of time was observed (F(3,73) = 0.12, p = 0.95). Thus, for subsequent analyses, telomere length was defined as the average across all available timepoints.

Table 3.

Telomere Length Means and Standard Deviations for each Study Visit

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Early Pregnancy | 1.66 | 0.26 |

| Mid Pregnancy | 1.67 | 0.28 |

| Late Pregnancy | 1.66 | 0.30 |

| Early Postpartum | 1.65 | 0.36 |

Note. Missing data ranges from 4 to 12 data points depending on the visit.

3.3 Indicators of childhood SES and telomere length

ANCOVAs were conducted to examine whether childhood SES was associated with telomere length (per average of all available datapoints), after adjustment for participant’s age, race, current household income, participant’s education level, participant’s marital status, BMI, exercise, smoking status, and depressive symptoms.1

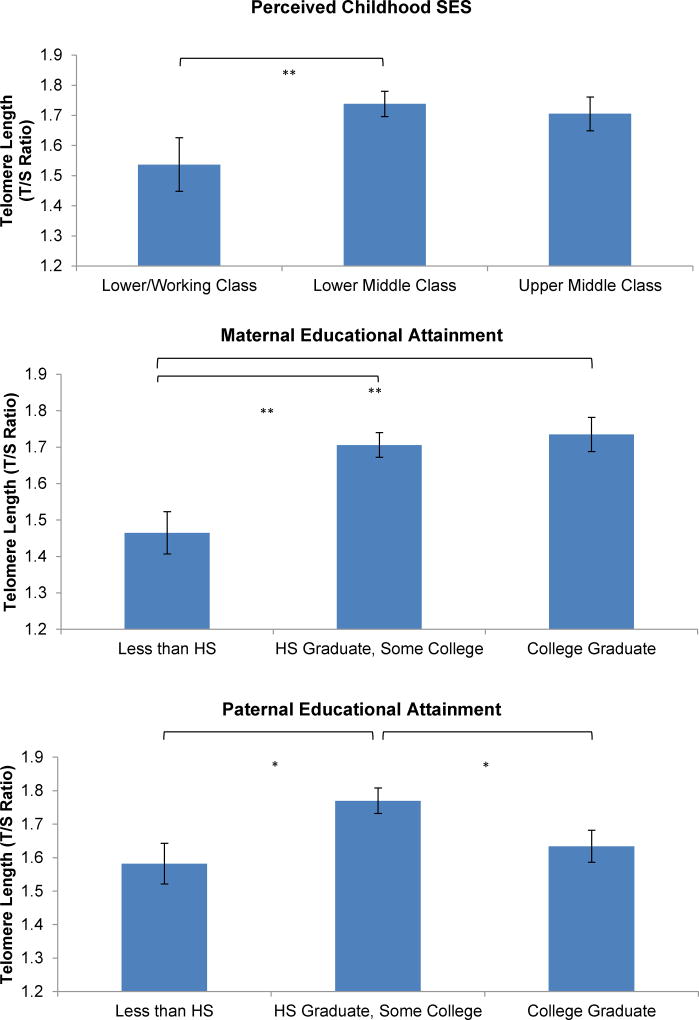

First, group differences by perceived childhood SES were examined. Because of a low response rate to lower class (n = 7), these women were collapsed with those from working class (n = 24) for analyses. After accounting for all specified covariates, as shown in Figure 1, a main effect was found for perceived childhood SES on telomere length (F(2, 81) = 4.26, p = 0.02, η2partial = 0.11); as expected, women in lower-middle class during childhood exhibited longer telomere length than women in lower-working class (p = 0.007). The effect between upper middle class compared to lower/working class did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07).

Figure 1. Relationships between Childhood SES Indicators and Telomere Length.

Main effects on telomere length were observed for perceived childhood SES (p = 0.02), maternal educational attainment (p = 0.001), and paternal educational attainment (p = 0.01). Post-hoc findings are signified with asterisks. Models were adjusted for age, race, current income level, participant education level, marital status, smoking status, pre-pregnancy body mass index, exercise, and depressive symptoms. HS refers to high school. *p < 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

Next, maternal education was examined. After accounting for all specified covariates, maternal educational attainment was associated with telomere length (F(2, 80) = 7.38, p = 0.001, η2partial = 0.18); women with a maternal educational attainment of high school graduate/some college (p = 0.001) or college graduate (p = 0.001) exhibited longer telomeres than those with a maternal educational attainment of less than high school.

Finally, paternal education was examined. Following adjustment for all specified covariates, paternal educational attainment was associated with telomere length (F(2, 68) = 4.58, p = 0.01, η2partial = 0.14). Consistent with expectations, women with a paternal educational attainment of high school graduate/some college were found to have longer telomeres compared to those with a paternal educational attainment of less than high school (p = 0.01). However, in contrast to hypotheses, women with a paternal educational attainment of high school graduate/some college exhibited longer telomere length than those with a paternal education of a college degree (p = 0.04). Findings in relation to childhood SES largely remained when women with pregnancy complications were excluded from analyses, with the exception that the post-hoc finding of longer telomeres among women with paternal education of high school graduate/some college exhibiting versus college degree was no longer significant.

3.4 Childhood trauma and telomere length

The effect of childhood trauma exposure on telomere length (per average of all available datapoints) was examined with separate ANCOVAs using the clinical cutoff on each respective subscale as well as the total trauma exposure. All models adjusted for participant’s age, race, current household income, participant’s education level, participant’s marital status, BMI, exercise, smoking status, and depressive symptoms. No significant effects on telomere length were observed in relation to emotional abuse (F(1, 76) = 0.05, p = 0.82, η2partial = 0.001), physical abuse (F(1, 76) = 0.48, p = 0.49, η2partial = 0.007), sexual abuse (F(1, 76) = 0.93, p = 0.34, η 2partial = 0.01), emotional neglect (F(1, 76) = 1.56, p = 0.22, η2partial = 0.02), physical neglect (F(1, 76) = 0.10, p = 0.75, η2partial = 0.002), or total trauma exposure (F(1, 76) = 0.08, p = 0.92, η2partial = 0.002).2

3.5 Perceived social support and telomere length

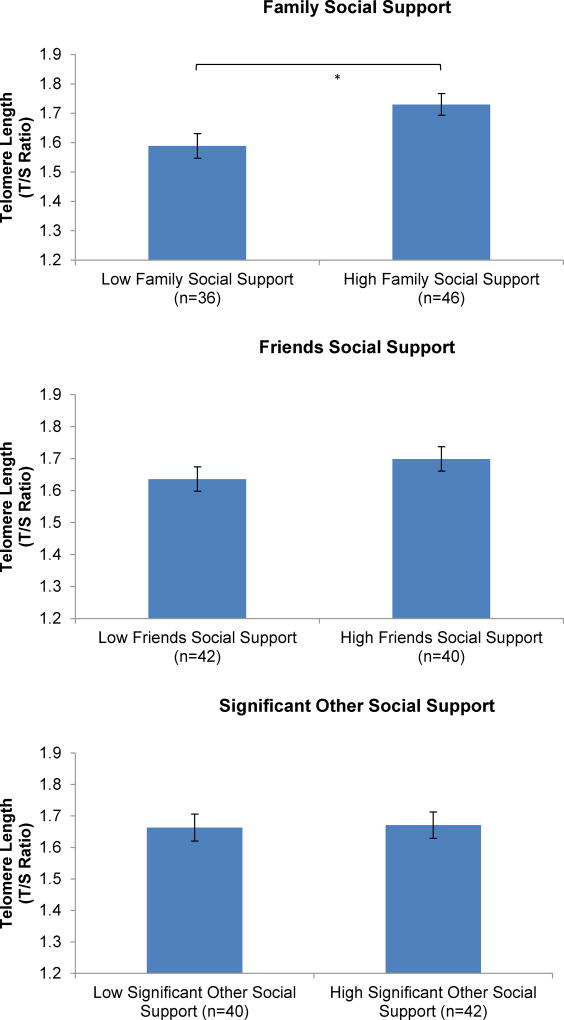

The effect of current social support on telomere length (per average of all available datapoints) was examined with ANCOVAs using a dichotomous median split on each respective subscale of social support: family, friends, and significant other. All models adjusted for participant’s age, race, current household income, participant’s educational attainment, participant’s marital status, BMI, exercise, smoking status, and depressive symptoms.1

A main effect was found for family social support (F(1, 81) = 5.31, p = 0.02, η2partial = 0.07) on telomere length. As expected, women with low social support exhibited shorter telomeres than those with high social support. Findings remained when women with pregnancy complications were excluded from analyses. No significant effects of social support on telomere length were observed in relation to friends (F(1, 81) = 1.28, p = 0.26, η2partial = 0.02) or significant others (F(1, 81) = 0.02, p = 0.90, η2partial = 0.00). Findings regarding significant other social support did not change when single women without romantic partners (n = 11) were excluded from analyses (p = 0.90).

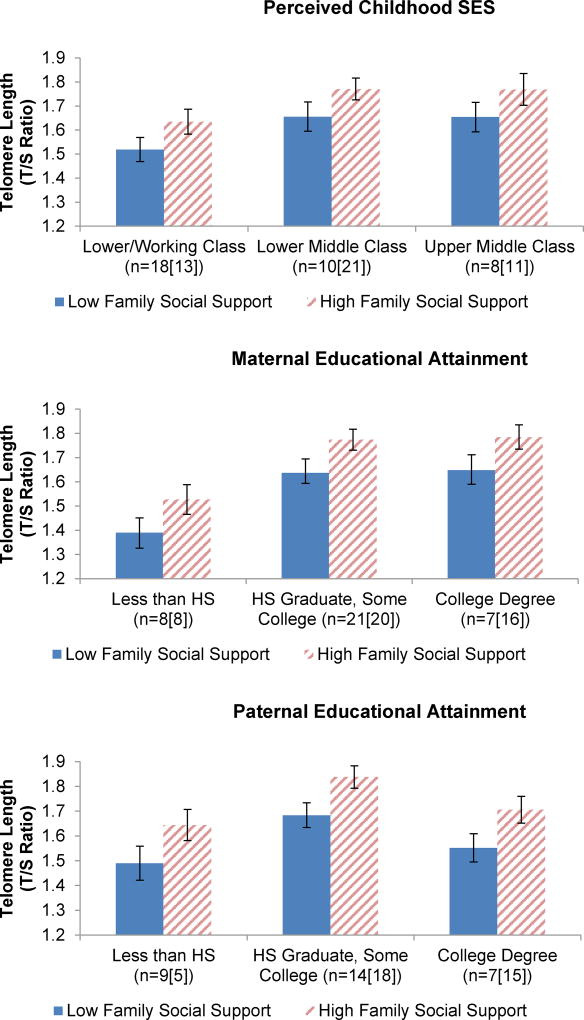

To determine whether the effect of family social support on telomere length was independent of childhood SES, ANCOVAs were conducted with both family social support and respective childhood SES indicators entered into the models. In educational attainment models, both family social support (ps < 0.02) and the respective parent education level (ps < 0.01) remained as significant main effects (Figure 3). In the perceived childhood SES model, as shown in Figure 3, family social support was not statistically significant (p = 0.07) while SES remained significant (p = 0.04). No significant interactions between family social support and childhood SES indicators on telomere length emerged (ps > 0.14).

Figure 3. Associations between Childhood SES Indicators and Family Social Support with Telomere Length.

No significant interactions between family social support and childhood SES indicators on telomere length emerged (ps ≥ 0.14). In educational attainment models, both family social support (ps < 0.02) and the respective parental educational indicator (ps < 0.01) remained as significant main effects. In the childhood SES model, family social support was not significant (p = 0.07) while SES remained significant (p = 0.04). Models were adjusted for age, race, current income level, participant education level, marital status, smoking status, pre-pregnancy body mass index, exercise, and depressive symptoms. HS refers to high school. (n=Low Family Social Support Group [High Family Social Support Group])

4. Discussion

The current data demonstrate effects of both early life exposure to socioeconomic adversity and current social support on PBMC telomere length in perinatal women. Specifically, lower childhood SES, defined by either perceived childhood social class, maternal education, or paternal education, was associated with shorter telomere length. In addition, greater social support, specifically from one’s family, predicted longer telomere length. These data add to a growing literature on risk factors linked with cellular aging.

Although mixed findings have been reported, a review of 31 studies linked low current SES, particularly educational attainment, to shorter telomeres (Robertson et al., 2013). Associations between current SES indicators and telomere length were not observed in the current study. While a few studies have examined telomeres in relation to a broad assessment of childhood adversity, even occasionally including an item related to SES (e.g., Kananen et al., 2010), data examining the unique effect of childhood SES on telomere length are limited. A few studies have linked adverse environmental exposures with shorter telomeres in children (Coimbra et al., 2017; Theall et al., 2017), though it is unclear whether these effects persevere into adulthood. Notably, in a sample of 135 men and women, fewer years of parental home ownership during childhood was associated with shorter telomeres (Cohen et al., 2013). In addition, childhood SES indicators were linked with telomere length in a cohort of adults approximately age 35; however, this relationship was not observed among older cohorts (i.e., adults aged 55 or 75 years) (Robertson et al., 2012). This may be due to survival bias or the changing meaning in SES indicators across generations (as discussed in Robertson et al., 2012). Consistent with these findings, the current data show that the effects of childhood SES are independent of current SES indicators, suggesting that this early life exposure has unique and lasting effects.

In the current study, childhood maltreatment (per the CTQ subscales and total exposure) was not significantly associated with telomere length. Prior data have shown a relationship between exposure to childhood trauma and shorter telomeres in adulthood (Tyrka et al., 2010). While other data have shown null findings (Glass et al., 2010) or only significant effects in combination with another stressor, such as separation from parents (Savolainen et al., 2014), associations may emerge in larger cohorts particularly in the context of multiple exposures (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2011); such cases were infrequent in the current study (n = 14). Per the current data and prior studies, early life adversity is negatively associated with adult telomere length. However, a growing literature in humans and animal models indicates that threat (e.g., trauma) versus deprivation (e.g., poverty) in early life has distinct neurodevelopmental consequences (McLaughlin et al., 2014). This may be relevant in the context of telomere length. Meta-analyses of early life adversity and telomere length demonstrate stronger relationships when comprehensive evaluations of adversity are used, rather than focusing on specific types of trauma (Ridout et al., 2017); Li et al., 2017; Hanssen et al., 2017). Additional research will elucidate the degree to which threat versus deprivation may have differing effects on telomere length.

The second main finding of this study was that women reporting lower current perceived social support exhibited shorter telomeres. Of note, this effect was found only in relation to perceived support from the family rather than friends or significant other. The stress associated with a lack of perceived family support may subsequently shorten telomeres. This is consistent with data that found, in a sample of 136 adults, shorter telomeres in those reporting greater ambivalence in relationships with parents (Uchino et al., 2012). Alternatively, it is possible social support plays a protective role with regard to telomere length; buffering the rate at which telomeres shorten during cell replication or mitigating the adverse effects of stress on telomeres. In the current study, low childhood SES was associated with shorter telomeres across both low and high levels of social support and thus did not serve as a protective mechanism. While other data have shown interactions between social relationship functioning and stressors on telomere length (Robles et al., 2016), suggesting a buffering effect, those studies were assessing current stressors. In our study, current family social support had a positive relationship with telomere length, but unsurprisingly, did not buffer historical exposure to childhood stress.

Formulation of one’s perception of support is largely rooted in early life interactions, with studies showing family interactions are indicative of later perceptions of support from various relationship sources. In addition, family support may be distinct from other sources of support (e.g., friends, significant other) in part by the duration and stability with which it is present or absent from an early age. Poor family support may be a reflection of other dynamics found in families under economic distress, such as harsh parenting strategies, greater family conflict, and a lack of routine (Chen and Miller, 2013). Thus, in the current study, the significant findings with family social support in particular could be a result of adverse early life family interactions, consistent with childhood vulnerability models (e.g., Miller et al., 2011). Prospective examinations of the associations between sources of perceived social support and telomere length would allow for stronger conclusions regarding the timing of such relationship dysfunction.

Early life deprivation of socioeconomic and relationship resources may contribute to biological dysregulation (Miller et al., 2011). A substantial literature, including both observational and experimental studies, has shown that childhood adversity is associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, including epigenetic changes in glucocorticoid receptors (e.g., Ehlert, 2013). Greater salivary cortisol levels as well as flatter diurnal cortisol slopes have been associated with reduced telomerase activity, a ribonucleoprotein reverse transcriptase which supports the maintenance of telomere length during cell replication (Tomiyama et al., 2012). In addition, glucocorticoids have been shown to increase oxidative stress damage, and oxidative stress has been implicated in telomere shortening (von Zglinicki, 2002). Early life stress has also been linked to elevated inflammatory markers, and the combined effects of oxidative stress and inflammation on telomere length may be particularly damaging (Rawdin et al., 2013). Thus, oxidative stress, HPA dysregulation, and inflammation are potential pathways by which early life deprivation may contribute to telomere length. Collectively, these data suggest biological pathways that may play a role in how modified stress-sensitivity contributes to increased rates of health conditions among adults with exposure to childhood adversity.

In this study, no change in telomere length was observed across pregnancy and postpartum visits. Further, examination of potential moderating effects of pregnancy-specific anxiety, per the Revised Pregnancy Distress Questionnaire (NUPDQ) as well as psychosocial factors of focus herein (childhood SES, trauma, social support) on change in telomere length across time showed no significant interactions (data not shown). These data are consistent with a prior study of 65 women which found no significant change in telomere length measured in early pregnancy (≤ 16 weeks gestation), 3 months postpartum, and 9 months postpartum (Leung et al., 2016). Although women who decreased their sugary beverage intake did exhibit telomere lengthening over this period (Leung et al., 2016), this was a function of this health behavior rather than pregnancy. In the current study, the average gestational age for the early pregnancy visit was 12 weeks; thus, it is unlikely that any changes compared to a pre-pregnancy state would be reflected within this relatively brief timeframe. The stability of telomere length across pregnancy visits, a time of considerable inflammatory changes in healthy pregnancies (e.g., Christian and Porter, 2014; Gillespie et al., 2016), suggests that pregnancy-related physiological changes do not affect telomere length. Pregnancy-induced physiological changes may differ from those induced by psychological stress in that compensatory mechanisms among multiple physiological systems interact to promote a healthy pregnancy.

In this study, childhood SES was defined using three indicators: self-reported social class, maternal educational attainment, and paternal educational attainment. A meta-analysis of 29 studies examining the effects of low childhood SES on adult health found that paternal educational attainment was the most commonly used indicator of SES during childhood (Galobardes et al., 2004). In the current sample, 26% of participants resided only with their mothers during childhood. However, similar effects emerged on telomere length in relation to both maternal and paternal education. It is possible that these indicators identified an overlapping subset of women. Of note, examination of correlations among SES indicators did not indicate multicollinearity (data not shown). Although these data show similar predictive value across measures, when possible, using multiple indicators in examining childhood SES allows for a more nuanced and comprehensive assessment.

One limitation of the current study is the use of PBMCs as the source for telomere length assay. PBMCs contain a mixture of different cells, including T cells, B cells, natural killer cells and monocytes. Telomere length in some cell types within PBMCs may be more sensitive to factors related to telomere shortening, such as chronic stress, as evidenced by a greater attenuation rate across 18 months in B cells and CD8+CD28− T cells. However, within individuals, PMBC telomere length is concurrently and longitudinally associated with telomere length of B and T cells specifically (Lin et al., 2016). Prior data showed a positive association between childhood SES and telomeres, as measured in adult CD8+CD28− T cells (Robertson et al., 2013); our findings extend this relationship to telomere length measured in PBMCs. In addition, while we considered multiple demographic variables and health behaviors known to affect telomere length, the inclusion of different types of psychological distress in models can result in statistical concerns, such as multicollinearity, and odd interpretations, particularly in a small sample size. Thus, although our key findings held in models with and without depressive symptoms as well as models with additional psychological distress variables as controls, identification of the most parsimonious model will be important for future research examining telomere length. Furthermore, while meaningful covariates were considered in these models (e.g., participant’s chronological age, race), paternal age was not captured. Paternal age at the time of birth has been positively associated with telomere length in adults (Broer et al., 2013) and thus should be considered in future studies. Finally, this study did not include analyses of telomere length in the neonate; maternal stress during pregnancy has been associated with shorter offspring telomeres (e.g., Marchetto et al., 2016). Examination of offspring telomere length in association with maternal early life exposures would be informative.

In terms of clinical applicability, maternal telomere length may play a role in maternal and offspring health. As mentioned earlier, chronological maternal age is strongly associated with increased risk for adverse maternal and fetal health outcomes. In the current sample, the age range was 18 to 33 years, with 22% of women over 30 years. Given the marked effects observed in cellular aging in relation to psychosocial exposures within women of this relatively young age range, examination of the predictive value of biological versus chronological age for adverse outcomes warrants examination, particularly among women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Moreover, these effects may have even greater relevance among women of advanced maternal age (i.e., ≥ 35 years), an important future direction in this line of inquiry.

Research to date pertaining to biological age is limited and has focused almost exclusively on placental telomere length (Biron-Shental et al., 2016). However, some data have found shorter maternal telomeres in women with gestational diabetes, recurrent miscarriages, and idiopathic pregnancy loss (e.g., Harville et al., 2010). Relatedly, evidence supports a strong relationship between maternal and offspring telomere length (Broer et al., 2013), and preterm birth has an intergenerational transmission pattern. Thus, it is plausible that factors affecting maternal telomere length have immediate and long-term consequences for maternal and offspring health.

While data have shown that shorter telomere length in mothers and fathers is associated with shorter telomeres in offspring, this relationship may not simply be due to heritability. In particular, there is an epigenetic-like transmission (non-genetic) of telomere length that has been described elsewhere (Aubert et al., 2012; Collopy et al., 2015) which applies to parents with very short telomeres. This may also be relevant for those within normal ranges of telomere length. Therefore our findings have potential significance for intergenerational transmission of telomere length. In other words, shorter telomeres from early adversity among perinatal women could theoretically be passed on to their offspring; this warrants examination in future studies.

Associations between maternal PBMC telomere length and adverse birth outcomes were unable to be examined in the current study. In this sample, only seven women exhibited adverse birth outcomes (i.e., preterm birth, low birth weight). Further, controlling for maternal age, African American women exhibited a trend toward longer telomeres than Whites (p = 0.10). Although not statistically significant in this cohort, this race effect is consistent with research (Hunt et al., 2008). Various biological factors, including replication rates of hematopoietic stem cells, may contribute to this racial difference (Hunt et al., 2008). Regardless of the cause, the predictive value of telomere length for health outcomes may be race-specific. Given that African American women experience markedly higher rates of PTB and other adverse maternal and fetal health outcomes, the examination of telomere length in association with birth outcomes requires a sample of sufficient size or racial homogeneity to permit statistical power for race-specific associations.

In sum, these data demonstrate that childhood socioeconomic status and social support, particularly from one’s family, are related to telomere length in pregnant women. Sample size and racial composition prevented examination of telomere length in relation to maternal health outcomes in the current study. Future research should examine the potential unique predictive power of biological age (i.e., telomere length as a marker), beyond chronological age, for adverse outcomes. These findings show that low childhood SES, independent of current SES indicators, and low family social support are risk factors of cellular aging in pregnant women. Both childhood SES and family social support remained significant predictors of telomere length in a combined model. These findings have relevance for understanding the mechanisms by which early life stress contributes to perinatal health. Examination of the role of maternal telomere length for adverse birth outcomes in these models would be informative.

Figure 2. Relationship between Social Support and Telomere Length.

A main effect on telomere length was observed in relation to family social support (p = 0.02), with women reporting lower versus higher social support exhibiting shorter telomeres. No effects on telomere length emerged with regard to social support from friends (p = 0.26) or significant others (p = 0.90). Models were adjusted for age, race, current income level, participant education level, marital status, smoking status, pre-pregnancy body mass index, exercise, and depressive symptoms.

Highlights.

Data are lacking regarding effects of pregnancy on telomere length.

Psychosocial predictors of telomere length in perinatal women are understudied.

Telomere length was stable across early, mid, and late pregnancy.

Low childhood SES and low family social support were linked to shorter telomeres.

Findings have implications for linking psychosocial stress and maternal health.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contributions of our Clinical Research Assistants and students to data collection. We also thank the staff and study participants at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Prenatal Clinic.

Role of Funding Sources: This study was supported by NICHD (HD067670, LMC) and NINR (R01NR013661, LMC). The project described was supported by Award Number Grant UL1TR001070 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Secondary analyses of significant models were conducted. First, significant models were run without depressive symptoms as a covariate. Main effects for indicators of childhood SES and current family social support on telomere length remained significant. In post-hoc analyses, only one small change occurred; the unexpected finding of shorter telomeres among women with fathers in the highest versus lowest category of educational attainment dropped below statistical significance (p = 0.066). Second, significant models were run with additional psychological distress variables were included as controls: 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983), 6-item State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Marteau and Bekker, 1992), 18-item Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (Lobel, 1996a), and the Prenatal Life Events Scale (PLES) (Lobel, 1996b; Lobel 2008). Main effects for indicators of childhood SES and current family social support on telomere length remained significant. In post-hoc analyses, only one small change occurred; the finding that women with a paternal educational attainment below high school exhibited shorter telomeres than those high school graduate or some college was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.067).

Analyses were also conducted using continuous childhood trauma exposure variables. In linear regression models, covariates were entered as the first step of the model and the respective childhood trauma exposure type in the second step of the model. No significant effects of childhood trauma on telomere length were observed (ps > 0.09)

Conflicts of Interest: JL is a co-founder and consultant of Telomere Diagnostics which did not have a role in the current study. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Aubert G, Baerlocher GM, Vulto I, Poon SS, Lansdorp PM. Collapse of telomere homeostasis in hematopoietic cells caused by heterozygous mutations in telomerase genes. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8:e1002696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SD, Cribbet MR. Social support sources matter: Increased cellular aging among adults with unsupportive spouses. Biological Psychology. 2016;115:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron-Shental T, Sadeh-Mestechkin D, Amiel A. Telomere homeostasis in IUGR placentas-A review. Placenta. 2016;39:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase: Their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS letters. 2005;579:859–862. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer L, Codd V, Nyholt DR, Deelen J, Mangino M, Willemsen G, Albrecht E, Amin N, Beekman M, de Geus EJ. Meta-analysis of telomere length in 19 713 subjects reveals high heritability, stronger maternal inheritance and a paternal age effect. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;21:1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JE, Roux AVD, Fitzpatrick AL, Seeman T. Low social support is associated with shorter leukocyte telomere length in late life: Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75:171–177. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828233bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Bommarito K, Madden T, Olsen MA, Subramaniam H, Peipert JF, Bierut LJ. Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19:1202–1211. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and health: Mediating and moderating factors. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, Iams JD. Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. 2009;23:750–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Porter K. Longitudinal changes in serum proinflammatory markers across pregnancy and postpartum: Effects of maternal body mass index. Cytokine. 2014;70:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB, Marsland AL, Casselbrant ML, Li-Korotky H-S, Epel ES, Doyle WJ. Childhood socioeconomic status, telomere length, and susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;34:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra BM, Carvalho CM, Moretti PN, de Mello MF, Belangero SIN. Stress-related telomere length in children: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2017;92:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collopy LC, Walne AJ, Cardoso S, de la Fuente J, Mohamed M, Toriello H, Tamary H, Ling AJ, Lloyd T, Kassam R. Triallelic and epigenetic-like inheritance in human disorders of telomerase. Blood. 2015;126:176–184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello MJ, Ross SA, Briel M, Anand SS, Gerstein H, Paré G. Association between shortened leukocyte telomere length and cardiometabolic outcomes systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2015;8:82–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:531–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert U. Enduring psychobiological effects of childhood adversity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1850–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: Systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:7–21. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SL, Porter K, Christian LM. Adaptation of the inflammatory immune response across pregnancy and postpartum in Black and White women. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2016;114:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass D, Parts L, Knowles D, Aviv A, Spector TD. No correlation between childhood maltreatment and telomere length. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:21–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Chicz-DeMet A, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Ethnic differences in adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol and corticotropin-releasing hormone during pregnancy. Peptides. 2007;28:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen LM, Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Epel ES. The relationship between childhood psychosocial stressor level and telomere length: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Research. 2017;5:6378. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2017.6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Williams MA, Qiu C-f, Mejia J, Risques RA. Telomere length, pre-eclampsia, and gestational diabetes. BMC Research Notes. 2010;3:113–119. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nater UM, Maloney E, Boneva R, Jones JF, Reeves WC. Childhood trauma and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: Association with neuroendocrine dysfunction. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:72–80. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SC, Chen W, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Srinivasan SR, Eckfeldt JH, Berenson GS, Aviv A. Leukocyte telomeres are longer in African Americans than in whites: The national heart, lung, and blood institute family heart study and the Bogalusa heart study. Aging Cell. 2008;7:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananen L, Surakka I, Pirkola S, Suvisaari J, Lönnqvist J, Peltonen L, Ripatti S, Hovatta I. Childhood adversities are associated with shorter telomere length at adult age both in individuals with an anxiety disorder and controls. PloS One. 2010;5:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J-P, Weng N-p, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, Glaser R. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C, Laraia B, Coleman-Phox K, Bush N, Lin J, Blackburn E, Adler N, Epel E. Sugary beverage and food consumption, and leukocyte telomere length maintenance in pregnant women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition Advanced online publication. 2016:1–3. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, He Y, Wang D, Tang J, Chen X. Association between childhood trauma and accelerated telomere erosion in adulthood: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2017;93:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Cheon J, Brown R, Coccia M, Puterman E, Aschbacher K, Sinclair E, Epel E, Blackburn EH. Systematic and cell type-specific telomere length changes in subsets of lymphocytes. Journal of Immunology Research. 2016;2016:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2016/5371050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M. The revised prenatal distress questionnaire (NUPDQ) Stony Brook, NY: State University of New York at Stony Brook; 1996a. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M. The Revised Prenatal Life Events Scale (PLES) Stony Brook: Stony BrookUniversity; 1996b. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel M, Cannella DL, Graham JE, DeVincent C, Schneider J, Meyer BA. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology. 2008;27:604. doi: 10.1037/a0013242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto NM, Glynn RA, Ferry ML, Ostojic M, Wolff SM, Yao R, Haussmann MF. Prenatal stress and newborn telomere length. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;215:94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.177. e91–94.e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1992;31:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Lambert HK. Childhood adversity and neural development: deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2014;47:578–591. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean M, Bisits A, Davies J, Woods R, Lowry P, Smith R. A placental clock controlling the length of human pregnancy. Nature medicine. 1995;1:460–463. doi: 10.1038/nm0595-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor G, Cardenas I, Abrahams V, Guller S. Inflammation and pregnancy: The role of the immune system at the implantation site. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1221:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müezzinler A, Zaineddin AK, Brenner H. A systematic review of leukocyte telomere length and age in adults. Ageing Research Reviews. 2013;12:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezza M, Giuseppina Pacilli M. Perceived social support from significant others, family and friends and several socio-demographic characteristics. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2002;12:422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rawdin B, Mellon S, Dhabhar F, Epel E, Puterman E, Su Y, Burke H, Reus V, Rosser R, Hamilton S. Dysregulated relationship of inflammation and oxidative stress in major depression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;31:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Révész D, Verhoeven JE, Milaneschi Y, de Geus EJ, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Dysregulated physiological stress systems and accelerated cellular aging. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014;35:1422–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout K, Levandowski M, Ridout S, Gantz L, Goonan K, Palermo D, Price L, Tyrka A. Early life adversity and telomere length: A meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson T, Batty GD, Der G, Fenton C, Shiels PG, Benzeval M. Is socioeconomic status associated with biological aging as measured by telomere length? Epidemiologic Reviews. 2013;35:98–111. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson T, Batty GD, Der G, Green MJ, McGlynn LM, McIntyre A, Shiels PG, Benzeval M. Is telomere length socially patterned? Evidence from the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. PloS One. 2012;7:e41805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Carroll JE, Bai S, Reynolds BM, Esquivel S, Repetti RL. Emotions and family interactions in childhood: Associations with leukocyte telomere length emotions, family interactions, and telomere length. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen K, Eriksson JG, Kananen L, Kajantie E, Pesonen A-K, Heinonen K, Räikkönen K. Associations between early life stress, self-reported traumatic experiences across the lifespan and leukocyte telomere length in elderly adults. Biological Psychology. 2014;97:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The association between depression and leukocyte telomere length: A meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32:229–238. doi: 10.1002/da.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MV, Gotman N, Yonkers KA. Early childhood adversity and pregnancy outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather AR, Alhaeeri AA, Montpetit A, Brumelle J, Filler K, Montpetit M, Mohanraj L, Lyon DE, Jackson-Cook CK. An integrative review of factors associated with telomere length and implications for biobehavioral research. Nursing Research. 2014;63:36–50. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Shirtcliff EA, Dismukes AR, Wallace M, Drury SS. Association between neighborhood violence and biological stress in children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171:53–60. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama AJ, O'Donovan A, Lin J, Puterman E, Lazaro A, Chan J, Dhabhar FS, Wolkowitz O, Kirschbaum C, Blackburn E. Does cellular aging relate to patterns of allostasis?: An examination of basal and stress reactive HPA axis activity and telomere length. Physiology & Behavior. 2012;106:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Kao H-T, Porton B, Marsella SA, Carpenter LL. Childhood maltreatment and telomere shortening: Preliminary support for an effect of early stress on cellular aging. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cawthon RM, Smith TW, Light KC, McKenzie J, Carlisle M, Gunn H, Birmingham W, Bowen K. Social relationships and health: Is feeling positive, negative, or both (ambivalent) about your social ties related to telomeres? Health Psychology. 2012;31:789–796. doi: 10.1037/a0026836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zglinicki T. Oxidative stress shortens telomeres. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2002;27:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JY, De Vivo I, Lin X, Fang SC, Christiani DC. The relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and telomere length in an occupational prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim IS, Tanner Stapleton LR, Guardino CM, Hahn-Holbrook J, Dunkel Schetter C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: Systematic review and call for integration. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2015;11:99–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-101414-020426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55:610–617. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]