Abstract

Presyncope and syncope are common medical findings, with greater than 40% estimated lifetime prevalence. These conditions are often elicited by postural stress and can be recurrent and accompanied by debilitating symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion. Therefore, it is critical for physicians to become familiar with diagnosis and treatment of common underlying causes of presyncope and syncope. In some patients, altered postural hemodynamic responses are due to failure of compensatory autonomic nervous system reflex mechanisms. The most common presentations of presyncope and syncope secondary to this autonomic dysfunction include vasovagal syncope, neurogenic orthostatic hypotension, and postural tachycardia syndrome. The most sensitive method for diagnosis is a detailed initial evaluation with medical history, physical examination, and resting electrocardiogram to rule out cardiac syncope. Physical examination should include measurement of supine and standing blood pressure and heart rate, to identify the pattern of hemodynamic regulation during orthostatic stress. Additional testing may be required in patients without clear diagnosis following initial evaluation. Management of patients should focus on improving symptoms and functional status, and not targeting arbitrary hemodynamic values. An individualized structured and stepwise approach should be taken for treatment starting with patient education, lifestyle modifications, and use of physical counter-pressure maneuvers and devices to improve venous return. Pharmacological interventions should only be added when conservative approaches are insufficient to improve symptoms. There are no gold standard approaches for pharmacological treatment in these conditions, with medications often used off-label and with limited long-term data for effectiveness.

Introduction

The autonomic nervous system rapidly engages physiological cardiovascular reflex mechanisms to maintain blood pressure (BP) during postural changes. The assumption of upright posture produces a shift of 500–1000 mL of blood to capacitance vessels in the lower extremities and splanchnic circulation.1 This gravitational pooling impairs venous return to the heart and preload, to reduce cardiac output and BP. The reduction in BP elicits unloading of arterial baroreceptors to elicit sympathetic activation and concurrent vagal withdrawal to the heart and blood vessels, to increase heart rate (HR), systemic vasoconstriction, and venous return.1 Neurohumoral responses are also engaged upon prolonged standing to conserve sodium and water. In healthy individuals, these compensatory mechanisms are sufficient to maintain hemodynamics during standing with a transient decrease in systolic BP (SBP; 10–15 mmHg), small increase in diastolic BP (DBP; 5–10 mmHg), and increase in HR (10–25 bpm).2

Abnormalities in autonomic reflex pathways can produce altered postural hemodynamic responses to promote presyncope, or feeling of imminent loss of consciousness due to symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion (e.g. lightheadedness, dizziness, blurred vision). Some patients may also experience syncope, defined as sudden transient loss of consciousness with inability to maintain postural tone and rapid spontaneous recovery.3 Presyncope and syncope are common findings in emergency departments, cardiology and neurology clinics, and primary care centers. Syncope accounts for up to 2% of emergency department visits and 6% of hospital admissions.4, 5 The estimated lifetime prevalence of syncope is up to 41%, with approximately 13% of patients having recurrent syncopal episodes.3 Given this high prevalence and impact on quality of life, it is critical to raise awareness on diagnostic and treatment approaches for these patients. This review focuses on common presentations of presyncope and syncope secondary to autonomic dysfunction including vasovagal syncope (VVS), neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH), and postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

General Evaluation and Treatment Considerations

As shown in Table 1, initial evaluation of patients presenting with presyncope or syncope should include a detailed medical history, physical examination with orthostatic vitals, and resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).3 This approach identifies cause of syncope in 23–60% of patients.6 Additional testing may be needed in patients with an unclear diagnosis, and should be guided by clinical signs and symptoms supporting specific underlying causes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Current Guideline Recommendations for Evaluation of Patients with Syncope

| Investigation | Utility | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Evaluation | ||

| Medical History | Essential | Document details of syncopal episodes, medications, other medical conditions, and family history. Rule out cardiac syncope. |

| Physical Examination | Essential | Detailed cardiovascular, neurologic, and other systems assessment. |

| Orthostatic Vitals | Essential | Blood pressure and heart rate should be measured while lying down (>5 minutes) and ideally again after 1 and 3 minutes of standing. |

| Electrocardiogram | Recommended | Rule out pre-existing cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular conduction abnormalities. |

| Additional Evaluation | ||

| Blood Work | Some Patients | In patients with evidence for specific underlying causes such as dehydration, anemia, benign infections, and diabetes mellitus. |

| Cardiovascular Testing or Monitoring | Some Patients | In patients with suspected cardiac syncope (e.g. echocardiogram, exercise stress testing, in- hospital telemetry, electrophysiological study) |

| Head-Up Tilt Table Testing | Some Patients | In patients with an unclear diagnosis after the initial evaluation, or in patients with convulsions or a seizure disorder. |

| Autonomic Function Testing | Some Patients | In patients with suspected autonomic nervous system impairment including orthostatic hypotension with blunted compensatory heart rate increase, or autonomic symptoms (e.g. constipation, neurogenic bladder, erectile dysfunction, decreased sweating). |

Medical History

Details of presyncopal or syncopal episodes, medications, and other medical conditions should be documented. Information related to episodes includes triggers (e.g. posture, pain, fatigue), frequency, time of day, prodromal symptoms, physical findings during and post-recovery, and witness accounts when available. Cardiac syncope due to underlying heart disease is potentially life-threatening.3 Therefore, personal and family history of cardiac disease (e.g. valvular and ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, arrhythmia, sudden cardiac death), and red flags for cardiac precipitants (e.g. episodes while supine or exertional onset, dyspnea, rapid palpitations) should be considered. Other medical conditions predisposing to syncope include volume depletion (e.g. dehydration), anemia, benign infections (e.g. urinary tract infection), and systemic diseases involving autonomic nerves (e.g. diabetes mellitus). Common contributory medications include diuretics, dopaminergic drugs, anticholinergics, venodilators, vasodilators (e.g. nitrates), α and β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, and tricyclic antidepressants. These cardiac and non-neurogenic causes should be ruled out before exploring diagnoses of VVS, nOH and POTS.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include orthostatic vital signs and detailed cardiopulmonary, neurologic, and other system assessments. For orthostatic vitals, BP and HR should be measured while supine (>5 minutes), and ideally again after 1, 3, 5, and 10 minutes of standing (see Supplemental Figure S1 for orthostatic vital sign assessment form). Detailed information on how to measure orthostatic vital signs is provided in this issue in, “Orthostatic hypotension – a practical approach to investigation and management.”7 Orthostatic symptoms should be documented; however, some patients may be asymptomatic. Passive head-up tilt (HUT) table testing to an angle >60° is not required for diagnosis, but may help document hemodynamics while reproducing symptoms of episodes, or in patients with confounding features such as convulsions or a seizure disorder.

Cardiac Testing

Resting 12-lead ECG is recommended to detect pre-existing cardiac disease and cardiac conduction abnormalities.3 An abnormal ECG may suggest underlying cardiac syncope. Additional testing may be needed in patients with suspicion of cardiac syncope (e.g. echocardiogram for structural heart disease, computed tomography of chest and abdomen for aortic dissection), but this should be driven by initial history and physical examination. Normal ECG findings are usually seen in VVS, nOH, and POTS.

Laboratory Tests

Routine laboratory testing has limited value in initial evaluation, and should only be performed based on clinical signs for specific illnesses.3 This may include complete blood count for anemia, basic metabolic panel for electrolyte disturbances, urinalysis for urinary tract infection, and blood glucose levels for diabetes.

Autonomic Function Testing

Standardized autonomic function testing should be considered in patients with signs of autonomic impairment including a drop in BP upon standing (>20/10 mmHg) with blunted compensatory HR increase (<15 bpm) suggesting autonomic failure, or presence of autonomic symptoms (e.g. decreased sweating, constipation, neurogenic bladder, sexual dysfunction).8 Autonomic testing requires continuous BP and HR monitoring and may necessitate referral to a tertiary care center. Autonomic function tests can include HUT, sinus arrhythmia, Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, cold pressor, isometric handgrip, quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing, and thermoregulatory sweat testing.9

General Treatment Considerations

Potential contributory medications should be discontinued when possible. Management should focus on improving symptoms and functional status, and not targeting arbitrary hemodynamic values. Providers should help manage patient expectations; treatment should lessen symptoms, but it is unlikely patients will be asymptomatic. Treatment should involve an individualized structured and stepwise approach, starting with patient education and non-pharmacological interventions, and adding pharmacological interventions only as needed. Patients should frequently document BP and HR, symptoms, precipitating factors, and timing for presyncopal and syncopal episodes. This will help to modify behaviors based on risk factors, and document efficacy of non-pharmacological or pharmacological interventions. There is limited long-term efficacy data for all pharmacological interventions used in these conditions, with recommendations often based on small studies performed in carefully selected patients. All medications discussed in this article are currently available in Canada, with the exception of droxidopa and ergotamine.

Vasovagal Syncope

An estimated 30–50% of patients presenting with syncopal episodes have VVS, a form of syncope associated with inappropriate reflex vasodilation and bradycardia (Table 2).10, 11 VVS is elicited in most patients by orthostatic stress, but can also result from exposure to pain, emotional distress, or medical settings.10 VVS is more common in females with a median age of onset at 17 years; however, it is the most common presentation of syncope across all age and gender groups.10 While VVS can be recurrent and impair quality of life, it is not associated with mortality.12, 13 In patients with frequent VVS, syncope tends to cluster over time with varying lengths of duration, prolonged breaks, and high rates of spontaneous remission.14, 15

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria and Clinical Features of Common Conditions Associated with Presyncope or Syncope Secondary to Autonomic Dysfunction

| Clinical Features | Vasovagal Syncope | Neurogenic OH | Postural Tachycardia Syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Criteria | Syncopal episode associated with hypotension and bradycardia; may occur in response to standing, pain, emotional stimuli or medical settings. | Progressive drop in BP ≥ 20/10 mmHg within 3 minutes of standing | HR increase ≥ 30 bpm within 10 minutes of standing; Absence of OH; Chronic symptoms orthostatic intolerance (≥ 6 months); Absence of other overt causes for tachycardia |

| Typical Onset Age | Any age; first episode usually in 2nd or 3rd decade | > 50 years | 13–50 years |

| Gender (% female) | 60% | 40% | >75% |

| Presyncope | + | +++ | ++++ |

| Syncope | +++ | ++ | +/− |

| Presence Orthostatic Symptoms | After prolonged sitting or standing | Immediate with sitting or standing | Immediate with sitting or standing |

| Presence OH | +/− (usually only at time of faint) | ++++ | − |

| Supine Plasma NE | Normal | Normal (MSA) or Low (PAF) | Normal |

| Standing Plasma NE | Normal | Minimal to No Increase | Normal or Exaggerated Increase (Hyperadrenergic) |

Abbreviations: OH, orthostatic hypotension; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; NE, norepinephrine; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PAF, pure autonomic failure.

Pathophysiology

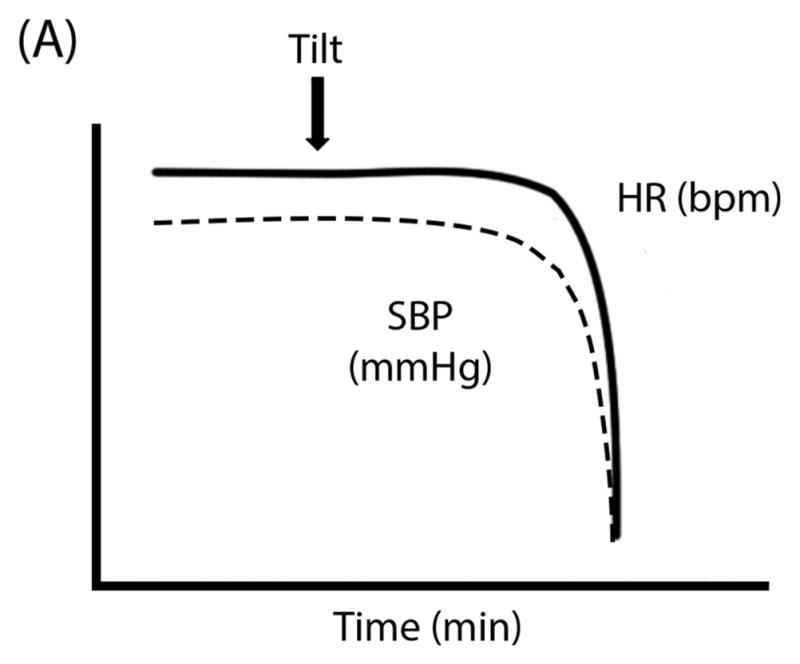

The hemodynamic pattern of VVS includes steady BP and HR upon standing for at least 30 seconds (and often several minutes), followed by rapid development of hypotension and bradycardia (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure S2B). In these patients, reduced venous return and cardiac preload during standing activates ventricular mechanoreceptors to increase cardiac contractility. When this is sensed as “overactive” by afferent unmyelinated C fibers, it produces reflex sympathetic withdrawal, vasodilation, and ultimately hypotension and bradycardia.16

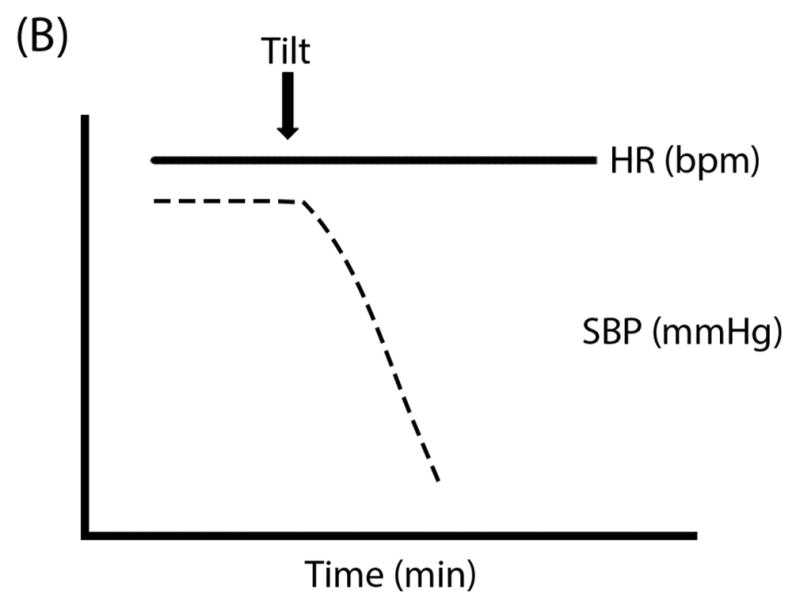

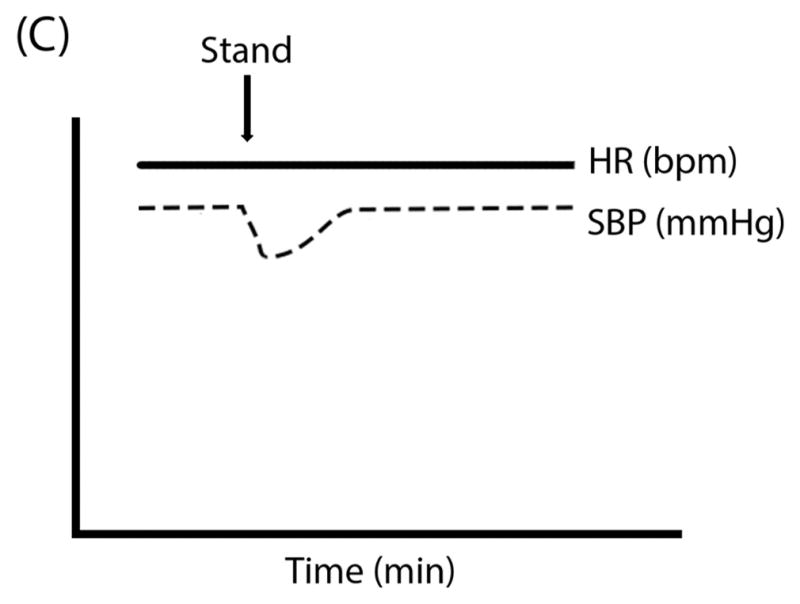

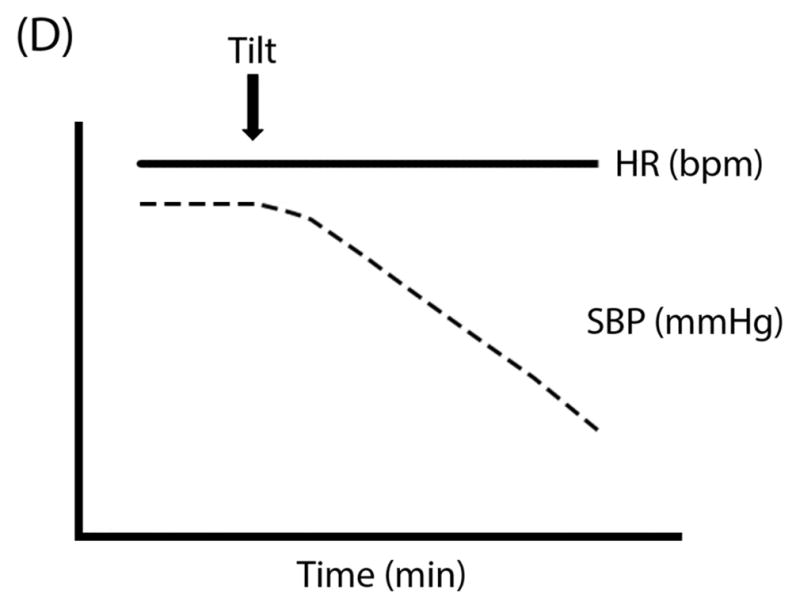

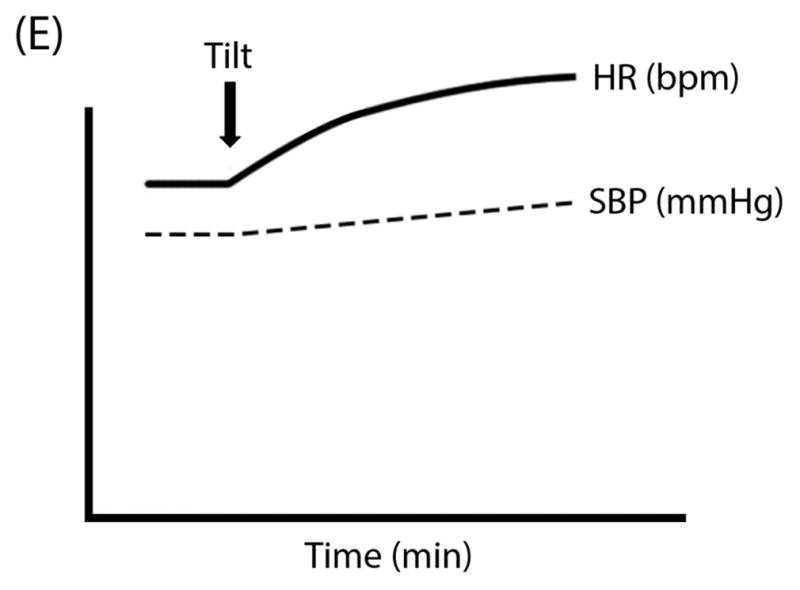

Figure 1. Schematic “Ball & Hill” Cartoons of heart rate (HR; solid line) and systolic blood pressure (SBP; dashed line) response patterns in different disorders. Panel A.

Vasovagal Syncope can often have preserved HR and SBP even after tilt until the SBP (the “ball”) suddenly falls off of a cliff; Panel B: Classical Orthostatic Hypotension (OH) shows a rapid drop in SBP with tilt, like a ball rolling down a steep hill; Panel C: Initial OH shows a very early and transient (but potentially large magnitude) drop in SBP with rapid recovery, like a ball rolling into and then out of a ditch; Panel D: Delayed OH has a more gradual drop in SBP that can take a prolonged time to reach the threshold for OH, like a ball steadily rolling down a gentle hill; and Panel E: Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is marked by an exaggerated increase in HR without OH.

Diagnostic Considerations

VVS is associated with classic prodromal symptoms including diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and pallor;17 however, older adults may be asymptomatic18. Patients may also experience symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion. Syncopal episodes should be transient, with patients remaining unconscious and motionless for a short time (usually <1 minute), followed by rapid spontaneous recovery and often long lasting post-recovery fatigue.10 Patients should not exhibit major changes in BP and HR from supine to standing positions; hypotension and bradycardia are only observed immediately prior to syncopal episodes. Short-term ambulatory monitoring may be useful in some patients to establish a symptom-rhythm correlation; however, given the short duration of recordings (a few days to weeks depending on the specific technology), syncopal episodes must be very frequent to detect with this approach. For infrequent, but bothersome spells, an implantable loop recorder under the skin may be considered. Laboratory investigations are usually normal (e.g. blood and urine tests, ECG, autonomic function tests), with abnormalities increasing likelihood of an alternate diagnosis.3 A clear history of features consistent with VVS in the absence of red flags is sufficient for clinical diagnosis.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Approximately 90% of patients can be controlled with education and non-pharmacological approaches. Patients should be educated that VVS is itself not associated with mortality,12, 13 to lie down at onset of prodromal symptoms, and to avoid triggers for syncopal episodes19. Dietary sodium and water intake should be increased in patients without renal failure, heart failure, or hypertension.3, 10 Approaches to increase venous return such as physical counter-pressure maneuvers (e.g. leg crossing, clenching the buttocks, inspiratory resistance) and devices (e.g. compression stockings or abdominal binders) may be useful.3 Orthostatic training may reduce syncopal episodes in VVS (e.g. repeated HUT testing or standing against a wall); however, there is limited efficacy data and poor patient compliance.3, 20 Patients managed by a syncope expert may report improvement in absence of therapy (“expectancy effect”).14

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological interventions should only be added in refractory patients. Small prospective studies have shown that midodrine, an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist pro-drug promoting vasoconstriction, improves orthostatic tolerance in VVS.21–23 A prospective, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled study is currently ongoing to determine effects of midodrine to prevent VVS (www.clinicaltrials.gov/NCT01456481).24 Due to its short duration of action (~4 hours), midodrine can be used as needed prior to upright activities with typical dosing at 8am, 12pm, and 4pm. Midodrine is often used as first line pharmacological therapy in VVS, but caution is recommended in patients with history of cardiovascular disease or urinary retention. Side effects can include piloerection, scalp pruritus, urinary retention in males, hypertension, and potential teratogenic effects. Patients should not lie down within 5 hours of taking midodrine due to risk of supine hypertension. In patients with inadequate responses to increased sodium and water intake and without cardiovascular disease, fludrocortisone (0.2 mg/day PO; synthetic mineralocorticoid) may be used as an adjuvant to enhance intravascular blood volume, either alone or in combination with midodrine. A recent multi-center controlled study showed significant risk reduction in frequent VVS after 2-week dose stabilization.25 Side effects include fatigue, nausea, hypokalemia, and hypertension. β-blockers and selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors have not convincingly proven effective in VVS.10 Additional studies are ongoing to determine efficacy of the synthetic norepinephrine precursor droxidopa (NCT02558972), selective β1-blocker metoprolol (NCT02123056), and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine (NCT02874937, NCT02500732) to prevent VVS.

Pacemaker Therapy

Initial uncontrolled studies showed symptomatic improvement and reduced syncopal episodes with dual-chamber pacing (DDD) with rate-drop response algorithm in VVS.26–28 Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled studies, however, showed a non-significant effect of active pacing to prevent syncopal recurrence in tilt-induced VVS.29, 30 A subsequent study showed efficacy of DDD with rate-drop response algorithm to reduce syncope recurrence in patients ≥40 years of age with severe asystolic VVS; however, this response was largely in tilt-negative patients limiting its utility.31 More recent studies demonstrated significant improvement in syncope recurrence with DDD with a closed-loop stimulation algorithm (DDD-CLS; Biotronik) compared to standard DDD pacing in asystolic tilt-positive VVS.32 Further studies of pacing in patients >40 years with recurrent VVS are ongoing.33 While CLS pacing may be more effective than other forms of pacing, there have not been any trials comparing CLS pacing to non-CLS pacing for the reduction of VVS.

Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is defined as a sustained decrease in SBP ≥20 mmHg or DBP ≥10 mmHg within 3 minutes of standing or greater than 60° HUT testing (Table 2).17 In nOH, the underlying cause of the postural drop in BP is impaired autonomic pathways. nOH accounts for up to 15% of syncope in general population cohorts, and approximately 24% of syncope-related cases in emergency room settings.12, 34, 35 nOH is more prevalent with advanced age, and is a common cause of hospitalization in patients >65 years of age.36 Importantly, nOH is a significant predictor of cardiovascular events and is associated with all-cause mortality.37

Pathophysiology

nOH results from impaired arterial baroreflex-mediated vasoconstriction to counteract gravitational pooling and reduced venous return to the heart during standing. The resulting hypotension can produce inadequate cerebral perfusion pressure to produce presyncopal symptoms or syncope. nOH can arise from primary neurodegenerative disorders or secondary to systemic conditions with peripheral autonomic nerve damage. Primary autonomic failure is due to α-synuclein protein deposits in central nervous system glial cells [e.g. multiple system atrophy (MSA)] or in postganglionic autonomic neurons [e.g. pure autonomic failure (PAF), Parkinson’s disease]. Primary autonomic failure is usually observed in patients >50 years of age. MSA is a rapidly progressing disease, whereas PAF and other peripheral forms have slower progression and generally better prognosis.38 The most common secondary cause of nOH is diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Other secondary causes include autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy, paraneoplastic syndrome, amyloidosis, and other various neuropathies (e.g. vitamin deficiency, drug-induced).

Diagnostic Considerations

Non-neurologic causes of OH should be excluded including dehydration, cardiac disease, and deleterious medications. Diagnosis of OH requires orthostatic vital signs. The three most common patterns of postural hemodynamic responses in OH include: (1) rapid drop in BP within 3 minutes of standing or tilt (classical variant; Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure S2C); (2) immediate, precipitous drop in BP within 15 seconds of standing, with recovery within 45 seconds (initial variant; Figure 1C); and (3) slow or ongoing, not reaching the diagnostic threshold until after 3 minutes (delayed variant; Figure 1D).3, 17 Ambulatory BP monitoring may be useful in some patients to provide information on BP lability and comorbidities such as postprandial hypotension and nocturnal hypertension. These devices, however, do not generally track body position, making it difficult to correlate changes directly to OH. Severely affected patients can only stand for a few seconds to minutes due to disabling symptoms including dizziness, lightheadedness, blurred vision, nausea, palpitations, tremulousness, weakness, fatigue, and headache. These symptoms are usually worse with upright posture and greatly improve or resolve with recumbence. Symptoms are usually worse early in the morning due to nocturnal pressure diuresis, and may be exacerbated by stimuli (e.g. prolonged standing, hot weather, alcohol, heavy meals, exercise). Non-cardiovascular autonomic symptoms may include gastroparesis, constipation, erectile dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, and anhidrosis. In MSA, motor symptoms may also be evident on neurologic examination including extrapyramidal signs or cerebellar ataxia. Initial blood tests that may be useful include complete blood count to exclude severe anemia, serum Vitamin B12 to exclude deficiency-related neuropathy, blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c to exclude diabetes, and serum and urine electrophoresis to exclude monoclonal proteins that might cause amyloidosis.

Patients with nOH due to autonomic failure often exhibit sustained postural BP drop with blunted compensatory HR increase (<15 bpm) (Supplemental Figure S2C). These patients should be referred for standardized autonomic function testing to determine integrity of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. HR variability during deep breathing (sinus arrhythmia) can be blunted in nOH suggesting cardiovagal impairment. BP and HR responses are also altered during forced expiratory effort (Valsalva maneuver; Supplemental Figure S3). Patients with nOH are often not able to generate appropriate α–adrenergic receptor-mediated sympathetic vasoconstriction to compensate for hypotension during strain (late phase II), and are not able to normalize venous return to produce a BP overshoot during release (phase IV). Rapid and deep breathing (hyperventilation) can produce profound drops in BP and presyncopal symptoms in nOH. Pressor responses to placing a hand in ice water (cold pressor) or to gripping weight with the hand at one-third maximal effort (isometric hand grip) are often also blunted in nOH suggesting impaired sympathetic adrenergic function. In patients with autonomic failure, supine and upright catecholamine concentrations may be useful to help distinguish between central and peripheral forms of the disease. Supine norepinephrine levels are usually normal in MSA, but often very low in PAF (<100 pg/mL) due to peripheral sympathetic denervation. The normal compensatory increase in norepinephrine upon standing, however, is blunted in MSA and other forms of autonomic failure. Detailed information on diagnostic tools for primary autonomic failure is provided in recent reviews.39, 40

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

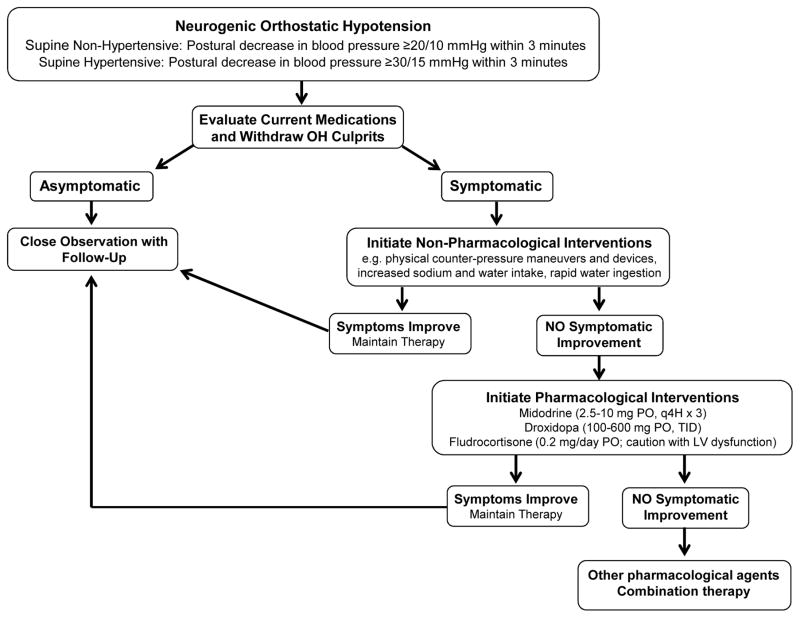

Treatment approaches for nOH are similar to idiopathic OH, and are described in detail in this issue in, “Orthostatic hypotension – a practical approach to investigation and management.”7 As shown in Figure 2, medications aggravating OH should be discontinued when appropriate (e.g. nitrates, diuretics, dopaminergic drugs, anticholinergics, antidepressants, sympatholytics). Patients should be educated on non-pharmacological approaches to improve venous return including physical counter-pressure maneuvers and devices.8 Lifestyle modifications include increased sodium and water intake (6–10 grams/day and 2–3 liters/day, respectively), physical activity to limit deconditioning, eating small frequent meals to prevent postprandial hypotension and avoiding alcohol, Valsalva-like maneuvers (e.g. heavy lifting, straining with defecation), and situations that increase core body temperature (e.g. hot showers).8 Rapid water ingestion can also be used as a rescue measure to acutely elevate BP (500 ml ingested within 2–3 minutes).8 This effect is observed within 5 minutes of ingestion, peaks between 20–40 minutes, and returns to baseline within 60–90 minutes. The pressor response is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system, with potentially greater BP responses in nOH patients with residual sympathetic tone.41

Figure 2.

Recommended approach for treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH). OH, orthostatic hypotension; LV, left ventricular; PO, orally; q4h, every 4 hours; TID, three times a day.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological interventions may be added, when conservative approaches are insufficient to improve symptoms (Figure 2).8, 35 In patients with cardiovascular disease, short-acting pressor agents are preferred such as midodrine (2.5–10.0 mg PO Q4H x3; α1-adrenergic agonist) and droxidopa (100–600 mg PO, TID; synthetic norepinephrine precursor). In nOH patients without cardiovascular disease, volume expansion with fludrocortisone (0.2 mg/day; mineralocorticoid agonist) can be considered, either alone or in combination with midodrine or droxidopa. In milder forms of OH, pyridostigmine (60 mg PO; cholinesterase inhibitor) can also be considered to preferentially increase standing BP.42 In patients with MSA, atomoxetine (18 mg PO; norepinephrine transporter inhibitor) and yohimbine (5.4 mg PO; α2-adrenergic antagonist) improve seated and standing BP by harnessing residual sympathetic tone.8 When these agents fail, other medications that can be tried in nOH include pseudoephedrine (30 mg PO; sympathomimetic), ergotamine (1 mg, PO) and octreotide (12.5–25 μg SC; somatostatin analog).8 Patients refractory to standalone therapy may benefit from combination therapy such as fludrocortisone (0.1–0.2 mg/day, PO) plus midodrine (5–10 mg, PO), ergotamine (1 mg, PO) plus caffeine (100 mg, PO), and midodrine (5–10 mg, PO) or pseudoephedrine (30 mg, PO) plus water (500 mL).43, 44 Ongoing studies for nOH include atomoxetine (NCT02784535), the investigational norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor TD-9855 (NCT02705755), and long-term efficacy of droxidopa (NCT02586623).

nOH and Supine Hypertension

At least 50% of nOH patients exhibit supine hypertension, defined as supine SBP ≥150 mmHg and DBP ≥90 mmHg.45 Since severity of supine hypertension correlates with magnitude of OH, a decrease in SBP ≥30 mmHg upon standing is a more appropriate diagnostic threshold in these patients.17 Supine hypertension complicates use of pressor agents to treat nOH, increases nocturnal pressure natriuresis, and contributes to cardiovascular end organ damage.45 The need to treat supine hypertension is illustrated by the finding that uncontrolled hypertension worsens risk of falls in patients with OH,46 perhaps by promoting pressure natriuresis. Non-pharmacological approaches include avoiding supine position during daytime, avoiding pressor agents while lying down or within 5 hours of bedtime, elevating the head of the bed 6–9 inches, and ingesting a sweet dessert (high carbohydrate) at bedtime to induce postprandial hypotension.45 In patients not controlled with these approaches, BP should ideally be monitored throughout the night in patients prior to initiating pharmacological therapy, as one-third of patients dip to normal BP levels during the night obviating need for treatment.47 In non-dipping patients, short-acting anti-hypertensive medications are recommended, with bedtime dosing and careful BP and symptom monitoring.

There are no medications currently approved for treatment of supine hypertension, but several drugs have been shown to acutely lower overnight BP in patients with nOH. First line therapy is transdermal nitroglycerin patch (0.2–2 mg/hour; removed 10–15 min prior to rising), with some patients experiencing limiting severe headaches. The α2-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine (0.1 mg PO) is effective to reduce nocturnal BP in MSA due to residual sympathetic tone; however, it can elicit paradoxical increases in BP in PAF with depressed sympathetic outflow. Despite this potential pressor effect in PAF, clonidine is not commonly used to raise BP in these patients. Additional medications shown to lower nocturnal BP in nOH include losartan (50 mg PO; angiotensin receptor blocker), eplerenone (50 mg PO; mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist), nebivolol (5 mg PO; β1 receptor antagonist), sildenafil (25 mg PO; phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor), and nifedipine (30 mg PO; calcium channel blocker).45 None of these medications improve morning orthostatic tolerance.

Postural Tachycardia Syndrome

POTS is characterized by excessive orthostatic tachycardia in the absence of hypotension and with chronic symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (Table 2).17 While the true prevalence is unknown, it is estimated that POTS affects 0.1–1% of the population in North America. At least 75% of patients are female, with typical onset between 13 to 50 years of age. Family history of orthostatic intolerance is reported in ~13% of patients.48 Syncope is not a predominant feature of POTS, but many patients experience presyncopal episodes that impair quality of life. Common comorbidities include chronic fatigue syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome hypermobility type, acrocyanosis, and gastroparesis.10 While natural history is currently unknown, POTS is not associated with significant mortality.

Pathophysiology

POTS is a clinical syndrome reflecting several heterogeneous disorders. The precise underlying causes remains unclear, but several subtypes have been proposed often with overlapping clinical features.10 First, hypovolemia is observed in ~70% of patients, perhaps due to impaired ability of the renin-angiotensin system to expand blood volume.10 This could further impair venous return during standing to elicit reflex sympathetic activation and tachycardia. Second, ~50% of patients have a neuropathic subtype associated with asymptomatic small fiber neuropathy affecting sympathetic innervation of the lower limbs.49 Third, up to 50% of patients have a hyperadrenergic phenotype characterized by tachycardia, SBP increase >10 mmHg, plasma norepinephrine >600 pg/mL, and symptoms of sympathetic activation (e.g. palpitations, tremulousness, anxiety) upon standing.10 Fourth, some patients report acute viral-like illnesses prior to POTS onset suggesting immune-mediated responses. Circulating antibodies to the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor (AChR), α1-adrenergic receptor, and β-adrenergic receptors have been discovered in POTS.50, 51 These autoantibodies could contribute to sympathetic activation; however, their importance in POTS pathogenesis is currently unknown. Fifth, some patients have mast cell activation disorder (MCAD) in the absence of an overt trigger, and present with severe episodic flushing of the face or upper trunk and hyperadrenergic features.52 Finally, norepinephrine transporter (NET) deficiency may contribute to POTS, by increasing synaptic norepinephrine levels to promote sympathetic activation. A loss of function mutation in the NET gene has been identified in one family with hyperadrenergic POTS.53 Decreased NET protein expression has also been observed in vein biopsies from POTS patients.54 Of interest, NET inhibitors (which are often used for treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions) mimic the clinical presentation of POTS.

Diagnostic Considerations

As shown in Table 2, diagnostic criteria for POTS includes: (1) HR increase ≥30 bpm within 10 minutes of standing; (2) absence of OH (drop in BP ≥20/10 mmHg); (3) chronic symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (>6 months); and (4) absence of acute physiological stimuli (e.g. exercise, panic attacks, pain, deconditioning), medications (e.g. sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, rebound tachycardia from β-blocker withdrawal), dietary influences (e.g. alcohol, caffeine), or other medical conditions (e.g. hyperthyroidism, anemia, dehydration) contributing to sinus tachycardia.3, 17 In adolescent patients (<19 years of age), there is a higher HR threshold (≥40 bpm change from supine to standing) due to physiological orthostatic tachycardia.17 Orthostatic symptoms can be cardiac or non-cardiac in nature and include palpitations, chest pain, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, headache, nausea, fatigue, tremulousness, exercise intolerance, sleep disturbances, and mental clouding. Orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms are often worse in the morning.55

Ambulatory ECG monitoring may be useful in some patients to document elevated HR, and may provide clarification related to sinus tachycardia versus other cardiac causes (e.g. paroxysmal supra-ventricular tachycardia), but many devices do not record posture or activity. Cardiovagal and sympathetic adrenergic function is usually intact or exaggerated in POTS patients during autonomic function testing. To detect hypovolemia, blood volume can be measured in nuclear medicine laboratories using indicator dye-dilution technique (intravenous infusion of 131I-labeled human serum albumin). In patients with suspected neuropathic subtype, neurologic examination and thermoregulatory sweat test may help identify small fiber neuropathy. Supine plasma norepinephrine is usually normal in POTS, but standing levels >600 pg/mL may indicate hyperadrenergic subtype. Routine testing of autoantibodies to adrenergic receptors or AChR is not recommended at this time, as their clinical utility remains uncertain. If a patient has features suggestive of an autoimmune disorder that could cause an autonomic disorder, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, then targeted testing may be warranted. In suspected MCAD, levels of methylhistamine (the primary metabolite of histamine) should be measured in urine collected within 4-hours of a severe spontaneous flushing episode. Finally, in patients with resting sinus tachycardia (≥100 bpm or 24-hour mean ≥90 bpm) and symptomatic palpitations, the diagnosis of inappropriate sinus tachycardia should be considered.

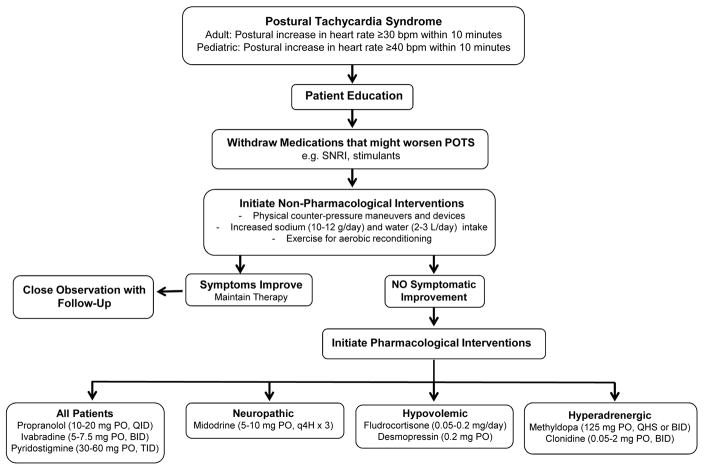

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

A multi-disciplinary approach is recommended involving physicians, nurses, physical therapists, and psychologists. As shown in Figure 3, patients should be educated that POTS is not associated with mortality. Non-pharmacological approaches should be initiated including withdrawal of medications that might worsen POTS (e.g. selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), increasing dietary sodium and water intake (10–12 grams/day and 2–3 L/day, respectively), physical counter-pressure maneuvers and devices to reduce venous pooling, and exercise to limit deconditioning.10 Patients should engage in recumbent or semi-recumbent exercise to minimize symptoms (e.g. rowing, recumbent cycling, swimming). Endurance exercise training reduces orthostatic tachycardia, improves quality of life, and restores blood volume, stroke volume, and left ventricular mass in POTS.56 Acute blood volume expansion with intravenous saline (1–2 L) may improve orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms in POTS.57 While useful for rescue during acute decompensation, chronic use is complicated by need for continued vascular access. Sinus node modification should not be encouraged, as POTS is associated with normal sinus rhythm and many patients do poorly post-procedure.

Figure 3.

Recommended approach for treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, PO, orally; QID, four times a day; BID, twice a day; TID, three times a day; q4h, every 4 hours; QHS, every bedtime.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological interventions may be needed in severely affected patients (Figure 3). Given heterogeneity of POTS, treatment must be individualized based on clinical features and underlying pathophysiology. Low dose propranolol (10–20 mg PO, QID; nonselective β-blocker) can be used as first line therapy and acutely improves orthostatic tachycardia, symptoms, and exercise capacity in POTS.58, 59 Higher doses are not well tolerated due to hypotension and fatigue, and other β-blockers have not been actively studied. Ivabradine (5.0–7.5 mg PO, BID), a selective If current channel blocker that slows HR, also produces symptomatic improvement in POTS.60 In patients with hypovolemia, volume expanders should be considered in combination with increased dietary sodium and fluid intake. Fludrocortisone (0.05–0.20 mg/day) can expand plasma volume, but there are no controlled studies showing efficacy in POTS. Desmopressin (0.2 mg PO) is a synthetic version of vasopressin that promotes renal sodium retention, and has been shown to acutely improve orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms in POTS.61 Midodrine (5–10 mg PO, q4H x3) reduces standing HR and improves symptoms in POTS,57 and may be particularly useful in patients with neuropathic subtype to improve systemic vascular resistance upon standing. In hyperadrenergic POTS, sympatholytics such as methyldopa (125 mg, PO QHS or BID) and clonidine (0.05–0.2 mg PO BID or preferably a long acting patch) may decrease central sympathetic tone to lower BP and HR. Clonidine, however, can produce drowsiness, fatigue, and mental clouding. Pyridostigmine (30–60 mg PO, TID), a peripheral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, is also effective to restrain tachycardia in POTS by enhancing parasympathetic outflow.62 This drug enhances bowel motility and is not recommended in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Ongoing studies for POTS include pyridostigmine (NCT00409435), ivabradine (NCT03182725), droxidopa (NCT02558972), vagal nerve simulation (NCT02281097; NCT03124355), and the psychostimulant modafinil (NCT01988883).

Conclusions

Presyncope and syncope often occur in response to orthostatic stress and secondary to autonomic dysfunction such as in VVS, nOH, and POTS. The most sensitive approach to determine underlying cause includes detailed medical history, physical examination with orthostatic vitals, and resting ECG. Orthostatic vitals are particularly helpful to differentiate conditions by showing hemodynamic patterns in response to standing. Management of these conditions should start with patient education, lifestyle modifications, and physical counter-pressure maneuvers and devices to improve venous return. Pharmacological interventions should only be added in patients failing conservative management. There are no gold standard treatment approaches and limited long-term efficacy data for pharmacological interventions in these conditions. Given the high prevalence and debilitating nature of symptoms in patients with presyncope and syncope, there is need to improve understanding of the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of these conditions.

Supplementary Material

Brief Summary.

Failure of cardiovascular autonomic reflex mechanisms can produce altered hemodynamic responses during standing, predisposing to presyncope and syncope to impair quality of life. Practical advice is given on initial evaluation and treatment of patients presenting with presyncopal or syncopal episodes. Specific information is provided on the most common presentations of presyncope and syncope secondary to autonomic dysfunction including vasovagal syncope, neurogenic orthostatic hypotension, and postural tachycardia syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL122507). SRR receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; Ottawa, ON, Canada) grant MOP142426 and the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada (CANet; London, ON, Canada) grants SRG-15-P01-001 and SRG-17-P27-001.

Footnotes

Disclosures: ACA, JN, and LL report no disclosures. SRR is a consultant for Lundbeck NA Ltd. and GE Healthcare, and has received research support from Medtronic Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith JJ, Porth CM, Erickson M. Hemodynamic response to the upright posture. J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;34:375–386. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1994.tb04977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chisholm P, Anpalahan M. Orthostatic hypotension: Pathophysiology, assessment, treatment and the paradox of supine hypertension. Intern Med J. 2017;47:370–379. doi: 10.1111/imj.13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, Cohen MI, Forman DE, Goldberger ZD, Grubb BP, Hamdan MH, Krahn AD, Link MS, Olshansky B, Raj SR, Sandhu RK, Sorajja D, Sun BC, Yancy CW. 2017 acc/aha/hrs guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines, and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daccarett M, Jetter TL, Wasmund SL, Brignole M, Hamdan MH. Syncope in the emergency department: Comparison of standardized admission criteria with clinical practice. Europace. 2011;13:1632–1638. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel PR, Quinn JV. Syncope: A review of emergency department management and disposition. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015;2:67–74. doi: 10.15441/ceem.14.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croci F, Brignole M, Alboni P, Menozzi C, Raviele A, Del Rosso A, Dinelli M, Solano A, Bottoni N, Donateo P. The application of a standardized strategy of evaluation in patients with syncope referred to three syncope units. Europace. 2002;4:351–355. doi: 10.1053/eupc.2002.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold ACR, SR Orthostatic hypotension - a practical approach to investigation and management. Can J Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibao C, Lipsitz LA, Biaggioni I American Society of Hypertension Writing G. Evaluation and treatment of orthostatic hypotension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013;7:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low PA, Tomalia VA, Park KJ. Autonomic function tests: Some clinical applications. J Clin Neurol. 2013;9:1–8. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, 2nd, Olshansky B, Shen WK, Calkins H, Brignole M, Raj SR, Krahn AD, Morillo CA, Stewart JM, Sutton R, Sandroni P, Friday KJ, Hachul DT, Cohen MI, Lau DH, Mayuga KA, Moak JP, Sandhu RK, Kanjwal K. 2015 heart rhythm society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:e41–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganzeboom KS, Mairuhu G, Reitsma JB, Linzer M, Wieling W, van Dijk N. Lifetime cumulative incidence of syncope in the general population: A study of 549 dutch subjects aged 35–60 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1172–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Chen MH, Chen L, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:878–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solbiati M, Casazza G, Dipaola F, Rusconi AM, Cernuschi G, Barbic F, Montano N, Sheldon RS, Furlan R, Costantino G. Syncope recurrence and mortality: A systematic review. Europace. 2015;17:300–308. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pournazari PSI, Sheldon R. High remission rates in vasovagal syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2017;3:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahota ISMC, Pournazari P, Sheldon RS. Clusters, gaps, and randomness: Vasovagal syncope recurrence patterns. J Am Coll Cardiol EP. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folino AF, Russo G, Porta A, Buja G, Cerutti S, Iliceto S. Modulations of autonomic activity leading to tilt-mediated syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, Benditt DG, Benarroch E, Biaggioni I, Cheshire WP, Chelimsky T, Cortelli P, Gibbons CH, Goldstein DS, Hainsworth R, Hilz MJ, Jacob G, Kaufmann H, Jordan J, Lipsitz LA, Levine BD, Low PA, Mathias C, Raj SR, Robertson D, Sandroni P, Schatz IJ, Schondorf R, Stewart JM, van Dijk JG. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2011;161:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieling W, Thijs RD, van Dijk N, Wilde AA, Benditt DG, van Dijk JG. Symptoms and signs of syncope: A review of the link between physiology and clinical clues. Brain. 2009;132:2630–2642. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raj SR, Coffin ST. Medical therapy and physical maneuvers in the treatment of the vasovagal syncope and orthostatic hypotension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffin ST, Raj SR. Non-invasive management of vasovagal syncope. Auton Neurosci. 2014;184:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufmann H, Saadia D, Voustianiouk A. Midodrine in neurally mediated syncope: A double-blind, randomized, crossover study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:342–345. doi: 10.1002/ana.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Lugones A, Schweikert R, Pavia S, Sra J, Akhtar M, Jaeger F, Tomassoni GF, Saliba W, Leonelli FM, Bash D, Beheiry S, Shewchik J, Tchou PJ, Natale A. Usefulness of midodrine in patients with severely symptomatic neurocardiogenic syncope: A randomized control study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:935–938. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samniah N, Sakaguchi S, Lurie KG, Iskos D, Benditt DG. Efficacy and safety of midodrine hydrochloride in patients with refractory vasovagal syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:A7, 80–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raj SR, Faris PD, McRae M, Sheldon RS. Rationale for the prevention of syncope trial iv: Assessment of midodrine. Clin Auton Res. 2012;22:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s10286-012-0167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheldon R, Raj SR, Rose MS, Morillo CA, Krahn AD, Medina E, Talajic M, Kus T, Seifer CM, Lelonek M, Klingenheben T, Parkash R, Ritchie D, McRae M Investigators P. Fludrocortisone for the prevention of vasovagal syncope: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benditt DG, Sutton R, Gammage MD, Markowitz T, Gorski J, Nygaard GA, Fetter J. Clinical experience with thera dr rate-drop response pacing algorithm in carotid sinus syndrome and vasovagal syncope. The international rate-drop investigators group. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1997;20:832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly SJ, Sheldon R, Roberts RS, Gent M. The north american vasovagal pacemaker study (vps). A randomized trial of permanent cardiac pacing for the prevention of vasovagal syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:16–20. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen ME, Chamberlain-Webber R, Fitzpatrick AP, Ingram A, Williams T, Sutton R. Permanent pacing for cardioinhibitory malignant vasovagal syndrome. Br Heart J. 1994;71:274–281. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly SJ, Sheldon R, Thorpe KE, Roberts RS, Ellenbogen KA, Wilkoff BL, Morillo C, Gent M Investigators VI. Pacemaker therapy for prevention of syncope in patients with recurrent severe vasovagal syncope: Second vasovagal pacemaker study (vps ii): A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2224–2229. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.17.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raviele A, Giada F, Menozzi C, Speca G, Orazi S, Gasparini G, Sutton R, Brignole M, Vasovagal S, Pacing Trial I. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of permanent cardiac pacing for the treatment of recurrent tilt-induced vasovagal syncope. The vasovagal syncope and pacing trial (synpace) Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1741–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brignole M, Menozzi C, Moya A, Andresen D, Blanc JJ, Krahn AD, Wieling W, Beiras X, Deharo JC, Russo V, Tomaino M, Sutton R International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology I. Pacemaker therapy in patients with neurally mediated syncope and documented asystole: Third international study on syncope of uncertain etiology (issue-3): A randomized trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2566–2571. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.082313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo V, Rago A, Papa AA, Golino P, Calabro R, Russo MG, Nigro G. The effect of dual-chamber closed-loop stimulation on syncope recurrence in healthy patients with tilt-induced vasovagal cardioinhibitory syncope: A prospective, randomised, single-blind, crossover study. Heart. 2013;99:1609–1613. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brignole M, Tomaino M, Aerts A, Ammirati F, Ayala-Paredes FA, Deharo JC, Del Rosso A, Hamdan MH, Lunati M, Moya A, Gargaro A, Committee BISS. Benefit of dual-chamber pacing with closed loop stimulation in tilt-induced cardio-inhibitory reflex syncope (biosync trial): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:208. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarasin FP, Louis-Simonet M, Carballo D, Slama S, Junod AF, Unger PF. Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension among patients presenting with syncope in the ed. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:497–501. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.34964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale GM, Valdes J, Brenner M. The treatment of primary orthostatic hypotension. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51:417–428. doi: 10.1177/1060028016689264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibao C, Grijalva CG, Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Griffin MR. Orthostatic hypotension-related hospitalizations in the united states. Am J Med. 2007;120:975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maule S, Milazzo V, Maule MM, Di Stefano C, Milan A, Veglio F. Mortality and prognosis in patients with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Funct Neurol. 2012;27:101–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Sharabi Y, Wu T. Survival in synucleinopathies: A prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2015;85:1554–1561. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurens B, Vergnet S, Lopez MC, Foubert-Samier A, Tison F, Fernagut PO, Meissner WG. Multiple system atrophy - state of the art. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:41. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nwazue VC, Raj SR. Confounders of vasovagal syncope: Orthostatic hypotension. Cardiol Clin. 2013;31:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Black BK, Ali Y, Farley M, Costa F, Diedrich A, Robertson RM, Biaggioni I, Robertson D. The pressor response to water drinking in humans : A sympathetic reflex? Circulation. 2000;101:504–509. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singer W, Opfer-Gehrking TL, McPhee BR, Hilz MJ, Bharucha AE, Low PA. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition: A novel approach in the treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1294–1298. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnold AC, Ramirez CE, Choi L, Okamoto LE, Gamboa A, Diedrich A, Raj SR, Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Shibao CA. Combination ergotamine and caffeine improves seated blood pressure and presyncopal symptoms in autonomic failure. Front Physiol. 2014;5:270. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Diedrich A, Black B, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Water potentiates the pressor effect of ephedra alkaloids. Circulation. 2004;109:1823–1825. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126283.99195.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biaggioni I. The pharmacology of autonomic failure: From hypotension to hypertension. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69:53–62. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.012161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gangavati A, Hajjar I, Quach L, Jones RN, Kiely DK, Gagnon P, Lipsitz LA. Hypertension, orthostatic hypotension, and the risk of falls in a community-dwelling elderly population: The maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly of boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:383–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okamoto LE, Gamboa A, Shibao C, Black BK, Diedrich A, Raj SR, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Nocturnal blood pressure dipping in the hypertension of autonomic failure. Hypertension. 2009;53:363–369. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, Benrud-Larson LM, Fealey RD, Vernino S, Lennon VA, Shen WK, Low PA. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: The mayo clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:308–313. doi: 10.4065/82.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibbons CH, Bonyhay I, Benson A, Wang N, Freeman R. Structural and functional small fiber abnormalities in the neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Yu X, Liles C, Khan M, Vanderlinde-Wood M, Galloway A, Zillner C, Benbrook A, Reim S, Collier D, Hill MA, Raj SR, Okamoto LE, Cunningham MW, Aston CE, Kem DC. Autoimmune basis for postural tachycardia syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000755. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vernino S, Low PA, Fealey RD, Stewart JD, Farrugia G, Lennon VA. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:847–855. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009213431204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shibao C, Arzubiaga C, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Raj S, Black B, Harris P, Biaggioni I. Hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in mast cell activation disorders. Hypertension. 2005;45:385–390. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000158259.68614.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, Jacob G, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:541–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lambert E, Eikelis N, Esler M, Dawood T, Schlaich M, Bayles R, Socratous F, Agrotis A, Jennings G, Lambert G, Vaddadi G. Altered sympathetic nervous reactivity and norepinephrine transporter expression in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:103–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.750471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brewster JA, Garland EM, Biaggioni I, Black BK, Ling JF, Shibao CA, Robertson D, Raj SR. Diurnal variability in orthostatic tachycardia: Implications for the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:25–31. doi: 10.1042/CS20110077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu Q, Levine BD. Exercise in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2015;188:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacob G, Shannon JR, Black B, Biaggioni I, Mosqueda-Garcia R, Robertson RM, Robertson D. Effects of volume loading and pressor agents in idiopathic orthostatic tachycardia. Circulation. 1997;96:575–580. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Ramirez M, Dupont WD, Robertson D. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: Less is more. Circulation. 2009;120:725–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arnold AC, Okamoto LE, Diedrich A, Paranjape SY, Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Gamboa A. Low-dose propranolol and exercise capacity in postural tachycardia syndrome: A randomized study. Neurology. 2013;80:1927–1933. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318293e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald C, Frith J, Newton JL. Single centre experience of ivabradine in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Europace. 2011;13:427–430. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coffin ST, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Orozco C, Black PW, Dupont WD, Robertson D, Raj SR. Desmopressin acutely decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raj SR, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Harris PA, Robertson D. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition improves tachycardia in postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:2734–2740. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.497594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.