Abstract

Context

Episodic dyspnea is one of the most common, debilitating and difficult-to-treat symptoms.

Objective

We conducted a pilot study to examine the effect of prophylactic FBT on exercise-induced dyspnea.

Methods

In this parallel, double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial, opioid-tolerant patients were asked to complete a 6 minute walk test (6MWT) at baseline, then a second 6MWT 30 minutes after a single dose of FBT (equivalent to 20-50% of their total opioid dose) or matching placebo. We compared dyspnea numeric rating scale (NRS, 0-10, primary outcome), walk distance, vital signs, neurocognitive function and adverse events between the two 6MWTs.

Results

Among 22 patients enrolled, 20 (91%) completed the study. FBT was associated with a significant within-arm reduction in dyspnea NRS between 0 and 6 minutes (mean change -2.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] -3.5, -1.3) and respiratory rate (mean change -2.6, 95% CI -4.7, -0.4). Placebo was also associated with a non-statistically significant decrease in dyspnea (mean change -1.1). Between arm comparison of dyspnea scores in the second 6MWT favored FBT, albeit not statistically significant (estimate -0.25, P=0.068). Global impression revealed more patients in the FBT group than placebo group reporting their dyspnea was at least “somewhat better” in the second 6MWT (4/9 vs. 0/11, P=0.03). The other secondary outcomes did not differ significantly between arms.

Conclusions

This study supports that prophylactic FBT was associated with a reduction of exertional dyspnea and was well-tolerated. Our findings support the need for larger trials to confirm the therapeutic potential of rapid-onset opioids.

Keywords: controlled clinical trials, dyspnea, fentanyl, neoplasms, opioid analgesics, physical exertion

Introduction

Episodic dyspnea is one of the most common, debilitating and difficult-to-treat symptoms in patients with advanced illnesses.(1) Transient and recurrent in nature, it is often induced by exertion and has a substantial impact on patients' daily function and quality of life.(2-4) Because of the paucity of treatment options for this challenging symptom, multiple professional organizations including the Institute of Medicine and National Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association identified dyspnea as a priority for research.(5, 6)

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis concluded that there was some evidence to support the use of opioids for dyspnea.(7) However, a majority of the included trials examined the use of opioids for patients with dyspnea at rest instead of episodic dyspnea. Because of their rapid onset of action, fast-acting fentanyl formulations may be particularly effective for episodic dyspnea.(8, 9) Several case series of oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate and intranasal fentanyl reported some benefits.(10-12) However, subsequent randomized controlled trials of subcutaneous fentanyl,(13) nebulized fentanyl (14, 15) and fentanyl pectin nasal spray (FPNS)(16) yielded mixed results compared to placebo.

Fentanyl buccal tablet (FBT) represents an attractive option for episodic dyspnea. It was approved by the US Food and Drugs Administration in 2006 for “breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant patients with cancer”. It has an absolute bioavailability of 65%.(17) The time to maximal effect (Tmax) was between 0.58-0.75 hour.(17, 18) FBT has been found in clinical trials to provide greater and more rapid breakthrough pain relief compared to placebo.(19, 20) A recent crossover trial of 6 patients reported that FBT had a faster onset of action than oral morphine for episodic dyspnea.(21) A better understanding of FBT's effect on exertional dyspnea may open up novel therapeutic options for this distress symptom. In this pilot placebo-control randomized controlled trial, we estimated the within-arm effects of prophylactic FBT and placebo on the intensity of exercise-induced episodic dyspnea. We also examined their effects on dyspnea at rest, 6 minute walk distance, neurocognitive function and adverse effects.

Patients and Methods

Patients

We enrolled adult patients with an active diagnosis of cancer from the Supportive Care outpatient clinics at MD Anderson Cancer Center who also met the following criteria: episodic dyspnea of at least 3/10 on a numeric rating scale (NRS), opioid tolerant at morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) of 60-130 mg for at least 1 week, ambulatory with or without walking aid and Karnofsky performance status ≥50%. Patients with dyspnea at rest ≥7/10, allergy to fentanyl, history of opioid abuse, required supplemental oxygen >6 L/minute, had a Memorial Delirium Rating Scale of ≥13/30, or any contraindication to completing a 6 minute walk test (6MWT) were excluded. The Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center approved this study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design

In this parallel, double-blind randomized trial (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01856114), patients completed a 6MWT at baseline, then rested until their dyspnea level returned to baseline+1 or lower for up to 1 hour. They were then randomly assigned to a single dose of FBT or placebo and waited for 30 minutes before completing a second 6MWT (corresponding to the Tmax of FBT).

Randomization and Blinding

After enrollment by our study coordinator, the study pharmacist assigned patients to the study intervention. Randomization was conducted in a 1:1 ratio using permuted blocks, stratified by baseline level of dyspnea numeric rating scale (NRS) at rest (i.e. 0-3 vs. 4-6). We concealed allocation using a secured website that was only accessible to the study pharmacist after patient enrollment. A research nurse who was not otherwise involved in this study administered the study medication without disclosing its identity. The patient, research coordinator conducting the study assessments and principal investigator were blinded to the study intervention and the randomization sequence. Maintenance of blinding was assessed at the end of study. Among patients, 13 (65%) stated they did not know the identity of the study medication, 4 (20%) were correct and 3 (15%) were incorrect in their guesses. Among research staff conducting the study assessments, 18 (90%) did not know the identity and 2 (10%) guessed correctly.

Study Interventions

The FBT were supplied by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and similar appearing placebo effervescent tablets were provided by a compounding pharmacy (Westchase Pharmacy Innovations, Houston, TX) because matching placebo were unavailable. The FBT/placebo tablet was placed in the buccal cavity between the upper cheek and gum until complete disintegration. We dosed the study medication using a proportional approach instead of a titration approach because only a single dose was administered in this study and a recent study found that proportional dosing of FBT was effective for breakthrough pain.(22) FBT was proportionally dosed to be equivalent to 20-50% of their total opioid dose over the past 24 hours because a previous study reported that a single rescue opioid dose proportional to 25-50% of the MEDD was safe and effective for relief of dyspnea at rest.(23) Based on the assumptions that 1 mg of IV morphine was equivalent to 10 mcg of fentanyl and that FBT had a bioavailability of 65%,(24) patients with MEDD of 60-65 mg/day received one tablet of 100 mcg, and those with MEDD of 66-130 mg/day received one tablet of 200 mcg.

Study Assessments and Endpoints

At baseline, we collected information on patient characteristics, such as age, sex, race and dyspnea level. The MicroLoop Spirometer (Micro Direct Inc, Lewiston, ME) was used at baseline to obtain vital capacity (VC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC, peak inspiratory flow, and peak expiratory flow.

Our primary outcome was dyspnea intensity “now” using a NRS that ranges from 0 (“no shortness of breath”) to 10 (“worst possible shortness of breath”).(25-27) This was assessed every minute during the 6MWTs, and then every 5 minutes during the rest period. 6MWT were carried out following guidelines from the American Thoracic Society and have been described in detail.(13, 28) We also assessed both dyspnea and fatigue using the 0-10 modified Borg scale before and after each 6MWT, and measured the distance walked every minute.(28) The minimal clinically significant difference was 1 point for both the NRS and modified Borg scale.(29, 30)

Other outcomes included vital signs, adverse effects and neurocognitive testing. We assessed heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation immediately before and after each 6MWT. Neurocognitive testing including finger tapping, arithmetic, reverse memory of digits and visual memory were assessed prior to medication administration and then after the second 6MWT according to published procedures.(16, 31) Adverse effects such as dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, and itchiness “now” were assessed immediately prior to medication administration and after the second 6MWT using an 11-point NRS, with 0 being absent and 10 denoting worst possible.

After completion of the second 6MWT, we also assessed patients' overall impression of change by asking them if their dyspnea was “a good deal worse”, “moderately worse”, “somewhat worse”, “almost the same, hardly any worse at all”, “about the same”, “almost the same, hardly any better at all”, “somewhat better”, “moderately better”, or “a good deal better”.(32, 33)

Statistical Analysis

This study was designed to estimate the effect of FBT on breathlessness in a within-patient comparison. We also included a placebo arm to examine the magnitude of placebo effect. Ten evaluable patients in the fentanyl arm provided 80% power to detect an effect size as small as 1.0 using a two-sided paired t-test with a significance level of 5% to compare the change of dyspnea between the first and second walk tests. 10 patients provided a 95% confidence for the standard deviation of the difference within treatment of (1.4, 3.7). This study is not powered for a direct comparison between FBT and placebo.

We summarized the baseline demographics using descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SD), ranges, 95% confidence intervals and frequencies. We calculated the mean difference between the first and second 6MWTs, along with 95% confidence interval for study outcomes. We used all available data for analysis and did not conduct imputation for missing data.

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

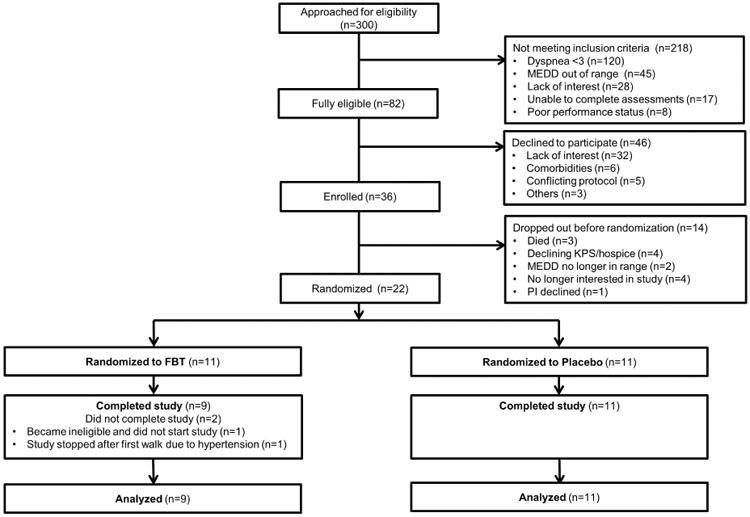

Among 22 patients enrolled between July 2014 and May 2016, 20 (91%) completed the study (Figure 1). The average age was 55 (range 31-72), 12 (60%) were female and 13 (65%) were White (Table 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

| FBT N=9 (%)a | Placebo N=11 (%)a | All patients N=20 (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (range) | 52 (31-67) | 57 (45-72) | 55 (31-72) |

| Female sex | 6 (66.7) | 6 (54.5) | 12 (60) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 7 (77.8) | 6 (54.5) | 13 (65) |

| Black | 2 (22.2) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (25) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 2 (10) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 7 () | 9 () | 16 () |

| College | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 2 (10) |

| Advanced degree | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Cancer type | |||

| Breast | 1 (11.1) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (15) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 (22.2) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (15) |

| Genitourinary | 2 (22.2) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (15) |

| Gynecologic | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5) |

| Lung | 3 (33.3) | 5 (45.5) | 8 (40) |

| Others | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (10) |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Metastatic/recurrent | 9 (100) | 10 (91) | 18 (90) |

| Locally advanced | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5) |

| Average dyspnea NRS during breakthrough episodes over the last week, mean (SD) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.9) | 5.2 (1.7) |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| COPD | 2 (22.2) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (15) |

| Heart failure | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5) |

| Asthma | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Bronchiectasis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Concurrent therapies (Scheduled) | |||

| Opioids | 9 (100) | 11 (100) | 20 (100) |

| Bronchodilators | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (10) |

| Steroids | 3 (33.3) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (20) |

| Supplemental oxygen | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bedside spirometry measures | |||

| FEV1 | 2 (1) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) |

| FEV1 % predicted | 66.4 (27.9) | 50.2 (23.9) | 57.9 (26.5) |

| FVC | 2.8 (1) | 2 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.0) |

| FVC % predicted | 73.3 (23.8) | 55.4 (20.2) | 63.9 (23.3) |

| FEV1 / FVC ratio (%) | 83.9 (16.9) | 90.7 (28.2) | 87.3 (22.8) |

| Morphine equivalent daily doses, median (interquartile range) in mg | 118 (85, 120) | 100 (70, 110) | 103 (73, 120) |

| Karnofsky performance status, mean (SD) | 72.2 (6.7) | 70 (8.9) | 71 (7.9) |

| Morphine equivalent daily dose (mg) | |||

| 60-65 | 0 | 2 (18) | 2 (10) |

| 66-130 | 9 (100) | 9 (82) | 18 (90) |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NRS, numeric rating scale; SD, standard deviation

unless otherwise specified

Dyspnea Scores

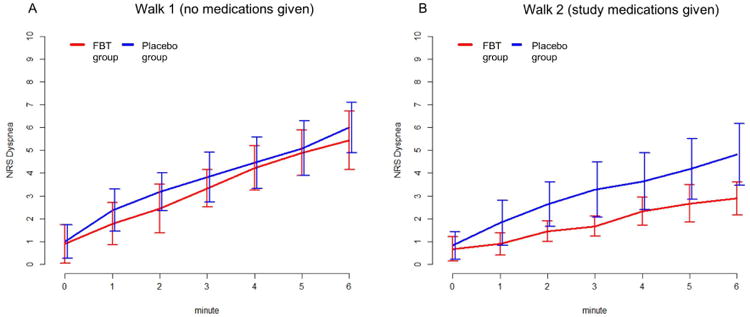

FBT was associated with a significant within-arm reduction in dyspnea NRS between 0 and 6 minutes (mean change -2.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] -3.5, -1.3) (Figure 2 and Table 2). Placebo was also associated with a non-statistically significant decrease in dyspnea (mean change -1.1, 95% CI -2.5, 0.2). Between arm comparison of dyspnea scores in the second 6MWT favored FBT, albeit not statistically significant (estimate -0.25, P=0.068). Dyspnea Borg scale showed similar findings favoring the FBT group (Table 2).

Figure 2. Change in Dyspnea Scores With and Without Study Medications.

(A) Without study medications, the two study groups had similar increase in dyspnea with exertion during walk 1. (B) With study medication, both study groups experienced a lower level of increase in dyspnea with exertion during walk 2 compared to the first walk. Patients who received fentanyl buccal tablet had a trend toward greater level of dyspnea relief compared to placebo (estimate -0.25, P=0.068). The error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

Table 2. Change in Dyspnea, Walk Distance and Fatigue Between with Fentanyl Buccal Tablet and Placeboa.

| Variables | Baseline walk test, mean (SD) | Second walk test, mean (SD) | Difference between first and second walk test, mean (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | FBT | Placebo | FBT | Placebo | FBT | |

| Dyspnea numeric rating scale (0-10) | ||||||

| 0 minutesb | 1 (1.2) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0.8 (1) | 0 (-0.7, 0.6) | -0.1 (-0.7, 0.5) |

| 6 minutes | 6 (1.8) | 5.4 (2.1) | 4.8 (2.2) | 2.9 (1.2) | -1.2 (-2.5, 0.1) | -2.6 (-3.9, -1.2) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 5 (1.9) | 4.6 (1.7) | 3.9 (2.4) | 2.1 (0.9) | -1.1 (-2.5, 0.2) | -2.4 (-3.5, -1.3) |

| Dyspnea Borg scale (0-10) | ||||||

| 0 minutesb | 1 (1.1) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.7 (0.8) | -0.2 (-0.9, 0.6) | -0.1 (-0.7, 0.6) |

| 6 minutes | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.1 (1.6) | 3.8 (2) | 2.4 (1.2) | -0.7 (-1.9, 0.5) | -1.7 (-2.6, -0.7) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 3.5 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.8) | 3 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.3) | -0.5 (-1.9, 0.8) | -1.6 (-2.9, -0.3) |

| Walk distance at 6 minutes (m) | 373.1 (92.5) | 410.9 (80.3) | 379.8 (92.4) | 409.9 (81.8) | 6.7 (-3.4, 16.9) | -1 (-22.3, 20.3) |

| Fatigue Borg Scale | ||||||

| 0 minutesb | 1.8 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | -0.3 (-1.2, 0.7) | -0.6 (-2.1, 1) |

| 6 minutes | 4 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.8) | 3.1 (2.5) | 1.3 (1.1) | -0.9 (-2.4, 0.6) | -2.1 (-3.6, -0.6) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 2.2 (3.1) | 1.9 (2.8) | 1.6 (2.9) | 0.3 (1) | -0.6 (-2.6, 1.4) | -1.6 (-4, 0.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FPNS, fentanyl pectin nasal spray; SD, standard deviation

Statistically significant values are highlighted in bold

The moment just prior to the 6 minute walk test, 30 minutes after FBT/placebo administration (i.e. at rest)

Walk Distance, Fatigue and Physiologic function

Comparing between the first and second 6MWT, we detected no significant difference in the change in fatigue and walk distance in both study arms (Table 2).

FBT was associated with a significant reduction in respiratory rate between the first and second 6MWTs (mean change -2.6, 95% CI -4.7, -0.4). Otherwise, no significant differences in heart rate, blood pressure or oxygen saturation were observed in either study arm (Table 3).

Table 3. Change in Physiologic Variables and Neurocognitive Testing Between with Fentanyl Buccal Tablet and Placebo.

| Variables | Baseline walk test, mean (SD) | Second walk test, mean (SD) | Difference between first and second walk test, mean (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | FBT | Placebo | FBT | Placebo | FBT | |

| Heart rate | ||||||

| 0 minutes | 82.9 (16) | 90.6 (12.9) | 83.9 (16.3) | 92.6 (12.8) | 1 (-4, 6) | 2 (-3.8, 7.8) |

| 6 minutes | 83.5 (19.6) | 97.9 (13.7) | 88.5 (21) | 94.6 (11.9) | 5 (-10, 20) | -3.3 (-8.4, 1.7) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 0.6 (16.2) | 7.3 (9.2) | 4.6 (11.6) | 2 (5.1) | 4 (-14.1, 22.1) | -5.3 (-13.4, 2.7) |

| Respiratory rate | ||||||

| 0 minutes | 17.5 (4.6) | 17.7 (3.1) | 17.5 (3.4) | 17.9 (2.9) | 0.1 (-2.4, 2.5) | 0.2 (-1.2, 1.6) |

| 6 minutes | 20.3 (5.2) | 20.4 (2.9) | 19.3 (4) | 18.1 (2.9) | -1 (-3.5, 1.5) | -2.3 (-3.9, -0.8) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 2.8 (3.4) | 2.8 (2.9) | 1.7 (3.4) | 0.2 (1.2) | -1.1 (-3.5, 1.3) | -2.6 (-4.7, -0.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||||

| 0 minutes | 115.1 (11.6) | 121.9 (12.7) | 121.3 (15.7) | 121.9 (14.5) | 6.2 (-3.8, 16.2) | 0 (-7.1, 7.1) |

| 6 minutes | 123.1 (18.1) | 131 (13.1) | 122.4 (13.7) | 129.9 (10.4) | -0.7 (-9.8, 8.4) | -1.1 (-11.2, 9) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 8 (15.7) | 9.1 (10.5) | 1.1 (16.5) | 8 (10.4) | -6.9 (-20.8, 7) | -1.1 (-13.6, 11.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| 0 minutes | 71 (7.4) | 77.1 (10.2) | 76.2 (12.1) | 77.3 (9.1) | 5.2 (0.5, 9.8) | 0.2 (-2.7, 3.1) |

| 6 minutes | 78.4 (8.8) | 77.9 (9.8) | 77.5 (12.3) | 75.4 (8.4) | -0.8 (-5.7, 4.1) | -2.4 (-6.8, 1.9) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 7.4 (7.3) | 0.8 (2.9) | 1.4 (5.3) | -1.9 (4.9) | -6 (-11.7, -0.3) | -2.7 (-7, 1.7) |

| Oxygen saturation | ||||||

| 0 minutes | 97.1 (2.2) | 97.9 (1.5) | 97.3 (1.2) | 98.2 (0.8) | 0.2 (-1.2, 1.5) | 0.3 (-0.5, 1.2) |

| 6 minutes | 97.4 (1.8) | 98.3 (1.9) | 96.8 (2.5) | 97.9 (1.9) | -0.5 (-1.9, 0.9) | -0.4 (-1.5, 0.6) |

| Δ (6-0) minutes | 0.1 (2.8) | 0.4 (1.7) | -0.5 (2.2) | -0.3 (1.4) | -0.6 (-3, 1.8) | -0.8 (-2.2, 0.6) |

| Neurocognitive testing | ||||||

| Tapping (average of 3 trials) | 35.7 (10.9) | 39.1 (8.5) | 41.8 (12.2) | 43.2 (7.7) | 6.2 (-1.2, 13.5) | 4 (0.5, 7.5) |

| Arithmetic | 62 (40.2) | 64.4 (76) | 59.1 (40.1) | 102.9 (191.9) | -2.9 (-11.6, 5.8) | 38.4 (-51, 127.9) |

| Reverse | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.4 (2.5) | 3.8 (2) | 0 (-1, 1) | -0.8 (-2.3, 0.7) |

| Visual | 5.7 (0.9) | 6 (0) | 5.5 (1) | 5.6 (0.9) | -0.2 (-0.6, 0.2) | -0.4 (-1.1, 0.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FBT, fentanyl buccal tablet; SD, standard deviation

Statistically significant values are highlighted in bold

Adverse Effects

FBT was associated with a significant improvement in one of the four neurocognitive tests between 6MWTs (tapping mean change 4, 95% CI 0.5, 7.5). There were no differences observed in the other neurocognitive tests (Table 3). FBT was well tolerated without an increase in dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, itchiness when assessed after medication administration (Table 4).

Table 4. Adverse Effects in FPNS and Placebo Armsa.

| Average Change (SD) | Number of patients with worse scores after the 6MWT (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | FBT | Placebo | FBT | Placebo |

| Dizzy | -0.4 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (18.2) |

| Drowsy | -0.1 (0.3) | 0.6 (2.3) | 0 | 2 (18.2) |

| Nausea | 0 (0) | -0.2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Itchiness | -0.3 (1) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (18.2) |

Abbreviations: FBT, fentanyl buccal tablet; SD, standard deviation; 6MWT, 6 minute walk test

Each adverse effect was measured using an 11-point numeric rating scale (0=none, 10=worst) immediate before drug administration and immediately after the second walk test (approximately 30 minutes later).

Global Symptom Evaluation

At the end of the study, a greater proportion of patients in the FBT group than the placebo group reported that their dyspnea was at least “somewhat better” in the second 6MWT compared to the first 6MWT (4/9 vs. 0/11, P=0.03).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, patients who received prophylactic, proportionally dosed FBT reported lower level of dyspnea with 6MWT and lower respiratory rate. This was in contrast to the placebo group in which no significant differences were detected. A single dose of FBT was well tolerated and did not result in significant neurocognitive adverse effect. Taken together, our study supports the need for larger trials to confirm the therapeutic potential of FBT for exertional dyspnea.

A 2013 systematic review on the effect of fentanyl for breathlessness included 13 studies and only 2 randomized controlled trials.(34) It concluded that “descriptive studies yielded promising results for the use of fentanyl for the relief of breathlessness; however, efficacy trials are lacking… require pilot studies to evaluate effective size, study procedures, and outcome measures.” In this study, patients who took FBT reported a statistically and clinically significant improvement in dyspnea NRS at the end of the 6MWT compared to without medication. Of interest is that the magnitude of change (2.4 points) is greater than 1 effect size and is higher than the cutoff for minimal clinical important difference (i.e. 1 point). Our findings are further supported by the observation that both Dyspnea Borg scale and global impression also showed similar effect favoring FBT.

These findings are consistent with our previous pilot studies examining other fentanyl formulations using a similar design, in which the intra-individual comparison allowed us to control for potentially confounding variables.(13, 16) In a double-blind, randomized controlled trial, we found that prophylactic subcutaneous fentanyl given at proportional dose of 15-25% of MEDD was safe and significantly improved dyspnea at rest, dyspnea at the end of 6MWT, walk distance, fatigue and respiratory rate in intra-individual comparison.(13) In another double-blind randomized controlled trial, FPNS at proportional dose of 15-25% of MEDD was also found to significantly improve dyspnea at rest, dyspnea at the end of 6MWT, and walk distance.(16) Interestingly, the walk distance and the dyspnea at rest did not improve significantly in the current study, which may be related to the differences of medication, timing of administration and variability among patients. More recently, Simon et al. also compared FBT to oral morphine for treatment (not prevention) of episodic dyspnea in an open-label, crossover trial. Although only 6 patients were recruited, the investigators reported that FBT had a non-statistically significant trend towards faster onset and greater efficacy for breakthrough dyspnea relief.(21)

We included a control arm in this study to better understand the impact of placebo effect. In contrast to previous studies in which the magnitude of placebo effect was comparable to the intervention effect,(13, 16) we found that the effect of FBT was quite a bit higher than placebo. Although our study was not powered for between-arm comparison, there was a clear trend, albeit not statistically significant, favoring the FBT arm for dyspnea improvement. This may be related to the use of a higher proportional dose of FBT (25-50%) compared to 15-25% for other agents.

Reassuringly, we found that FBT proportional to 20-50% of total daily dose did not have any significant impact on neurocognitive function. Patients also did not report any short term opioid adverse effects such as dizziness or drowsiness. Instead, we observed a few individuals with nocebo effect. Future studies should examine the longer term adverse effects and addictive potential of FBT.

Proportional dosing for rapid onset fentanyl formulations has been a contentious issue.(35) On the one hand, the pivotal studies resulting in approval of these agents all used a titration approach;(19, 36) and some investigators reported the lack of association between baseline MEDD and effective dose for pain relief.(37) On the other hand, the rescue dose of all other classes of opioids are typically proportionally dosed, and it is unclear that the pharmacokinetic of these fentanyl formulations is significantly different. Indeed, Mercadente et al. reported that proportionally dose fentanyl products, including FBT, FPNS, sublingual fentanyl were effective for breakthrough pain management.(38-41) Our study lends support to the use of proportionally dosed FBT for episodic dyspnea, which eliminates the cumbersome process of titration.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size can result in false negative findings. Instead of statistically significance, it is important to focus on the magnitude of effect and distribution, which would allow us to estimate the effect size for future study power calculation. A crossover trial may improve the power; however, the requirement for a washout period would make this a multiple day study and potentially increase the rate of attrition. Second, we included multiple exploratory outcomes; any positive findings should be considered hypothesis generating. Third, patients were recruited from the Supportive Care Center at a single tertiary care cancer center. Thus, the findings in this explanatory study may not be generalizable to other settings. Fourth, the maximal MEDD was limited to 130 mg/day in this study because it was unclear if proportionally dosed FBT could be safely given when we designed this study. Based on the findings from this trial, future studies should consider including patients with higher MEDD. Fifth, we only examined a single dose under carefully designed experimental conditions. Pragmatic studies are needed to examine the use of FBT in real life situations.

In summary, this pilot study provided promising results to support that prophylactic, proportionally dose FBT may improve exertional dyspnea. Adequately powered randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm its effect compared to placebo. Future studies should also consider testing the use of FBT for longer term and in the home setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study personnel and study medications were supported by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. through an investigator-initiated research award to D.H. D.H. was also supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant (R21CA186000-01A1) and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (MRSG-14-1418-01-CCE), and the Andrew Sabin Family Fellowship. M.P. and D.L. were supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA016672).

The funding sources were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Simon ST, Weingartner V, Higginson IJ, Voltz R, Bausewein C. Definition, categorization, and terminology of episodic breathlessness: consensus by an international Delphi survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:828–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy SK, Parsons HA, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, Bruera E. Characteristics and correlates of dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:29–36. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon ST, Bausewein C, Schildmann E, et al. Episodic breathlessness in patients with advanced disease: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:561–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercadante S, Aielli F, Adile C, et al. Epidemiology and Characteristics of Episodic Breathlessness in Advanced Cancer Patients: An Observational Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Board IOMNCP. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck H, Brody AA, Campbell ML, et al. Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association 2015-2018 Research Agenda. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2015;17:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes H, McDonald J, Smallwood N, Manser R. Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:Cd011008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011008.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MJ, Hui D, Currow DC. Opioids, Exertion, and Dyspnea: A Review of the Evidence. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:194–200. doi: 10.1177/1049909114552692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benitez-Rosario MA. Fentanyl for episodic dyspnoea in cancer patients. Annals of palliative medicine. 2014;3:4–6. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2014.01.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benitez-Rosario MA, Martin AS, Feria M. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate in the management of dyspnea crises in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:395–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitte T, Bausewein C. Intranasal fentanyl for episodic breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:e3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauna AA, Kang SK, Triano ML, Swatko ER, Vanston VJ. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate for dyspnea in terminally ill patients: an observational case series. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:643–648. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui D, Xu A, Frisbee-Hume S, et al. Effects of prophylactic subcutaneous fentanyl on exercise-induced breakthrough dyspnea in cancer patients: a preliminary double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen D, Alsuhail A, Viola R, Dudgeon DJ, Webb KA, O'Donnell DE. Inhaled fentanyl citrate improves exercise endurance during high-intensity constant work rate cycle exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotrach HG, Bourbeau J, Jensen D. Does nebulized fentanyl relieve dyspnea during exercise in healthy man? Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985) 2015;118:1406–1414. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01091.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui D, Kilgore K, Park M, Williams J, Liu D, Bruera E. Impact of Prophylactic Fentanyl Pectin Nasal Spray on Exercise-Induced Episodic Dyspnea in Cancer Patients: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lecybyl R, Hanna M. Fentanyl buccal tablet: faster rescue analgesia for breakthrough pain? Future oncology (London, England) 2007;3:375–379. doi: 10.2217/14796694.3.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darwish M, Tempero K, Kirby M, Thompson J. Relative bioavailability of the fentanyl effervescent buccal tablet (FEBT) 1,080 pg versus oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate 1,600 pg and dose proportionality of FEBT 270 to 1,300 microg: a single-dose, randomized, open-label, three-period study in healthy adult volunteers. Clin Ther. 2006;28:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portenoy RK, Taylor D, Messina J, Tremmel L. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of fentanyl buccal tablet for breakthrough pain in opioid-treated patients with cancer. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2006;22:805–811. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210932.27945.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slatkin NE, Xie F, Messina J, Segal TJ. Fentanyl buccal tablet for relief of breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant patients with cancer-related chronic pain. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon ST, Kloke M, Alt-Epping B, et al. EffenDys-Fentanyl Buccal Tablet for the Relief of Episodic Breathlessness in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Randomized, Morphine-Controlled, Crossover, Phase II Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercadante S, Gatti A, Porzio G, et al. Dosing fentanyl buccal tablet for breakthrough cancer pain: dose titration versus proportional doses. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:963–968. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.683112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, MacEachern T, Ripamonti C, Hanson J. Subcutaneous morphine for dyspnea in cancer patients. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:906–907. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-9-199311010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darwish M, Kirby M, Robertson P, Jr, Tracewell W, Jiang JG. Absolute and relative bioavailability of fentanyl buccal tablet and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:343–350. doi: 10.1177/0091270006297749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorman S, Byrne A, Edwards A. Which measurement scales should we use to measure breathlessness in palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:177–191. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gift AG, Narsavage G. Validity of the numeric rating scale as a measure of dyspnea. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui D, Morgado M, Vidal M, et al. Dyspnea in Hospitalized Advanced Cancer Patients: Subjective and Physiologic Correlates. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:274–280. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva C, et al. Minimal Clinically Important Differences in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in Cancer Patients: A Prospective Study. Cancer. 2015;121:3027–3035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ries AL. Minimally clinically important difference for the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire, Borg Scale, and Visual Analog Scale. COPD. 2005;2:105–110. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruera E, Miller MJ, Macmillan K, Kuehn N. Neuropsychological effects of methylphenidate in patients receiving a continuous infusion of narcotics for cancer pain. Pain. 1992;48:163–166. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90053-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redelmeier DA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein RS. Assessing the minimal important difference in symptoms: a comparison of two techniques. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1215–1219. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon ST, Koskeroglu P, Gaertner J, Voltz R. Fentanyl for the relief of refractory breathlessness: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:874–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui D, E B. Breakthrough Pain In Cancer Patients: The Need For Evidence. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portenoy RK, Messina J, Xie F, Peppin J. Fentanyl buccal tablet (FBT) for relief of breakthrough pain in opioid-treated patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:223–233. doi: 10.1185/030079906X162818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagen NA, Fisher K, Victorino C, Farrar JT. A titration strategy is needed to manage breakthrough cancer pain effectively: observations from data pooled from three clinical trials. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:47–55. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercadante S, Porzio G, Aielli F, Averna L, Ficorella C, Casuccio A. The use of fentanyl buccal tablets for breakthrough pain by using doses proportional to opioid basal regimen in a home care setting. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2335–2339. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mercadante S, Prestia G, Casuccio A. The use of sublingual fentanyl for breakthrough pain by using doses proportional to opioid basal regimen. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1527–1532. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.826640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mercadante S, Adile C, Cuomo A, et al. Fentanyl Buccal Tablet vs. Oral Morphine in Doses Proportional to the Basal Opioid Regimen for the Management of Breakthrough Cancer Pain: A Randomized, Crossover, Comparison Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercadante S, Aielli F, Adile C, Costanzi A, Casuccio A. Fentanyl Pectin Nasal Spray Versus Oral Morphine in Doses Proportional to the Basal Opioid Regimen for the Management of Breakthrough Cancer Pain: A Comparative Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]