Abstract

Gap junctions provide the basis for electrical synapses between neurons. Early studies in well-defined circuits in lower vertebrates laid the foundation for understanding various properties conferred by electrical synaptic transmission. Knowledge surrounding electrical synapses in mammalian systems unfolded first with evidence indicating the presence of gap junctions between neurons in various brain regions, but with little appreciation of their functional roles. Beginning at about the turn of this century, new approaches were applied to scrutinize electrical synapses, revealing the prevalence of neuronal gap junctions, the connexin protein composition of many of those junctions, and the myriad diverse neural systems in which they occur in the mammalian CNS. Subsequent progress indicated that electrical synapses constitute key elements in synaptic circuitry, govern the collective activity of ensembles of electrically coupled neurons, and in part orchestrate the synchronized neuronal network activity and rhythmic oscillations that underlie fundamental integrative processes.

Keywords: Neuronal gap junctions, Mixed chemical/electrical synapses, Connexins, Cell localization, Ultrastructural diversity, Protein composition

1. Introduction

Electrical synapses, formed by gap junctions between neurons, have been studied extensively in the CNS of non-mammalian vertebrates beginning in the mid-20th century, and more recently have received intensive scrutiny in the mammalian CNS following the development and application of an arsenal of genetic and molecular biological tools. To many established scientists in the neuroscience community who are uninitiated with respect to the many decades of literature on electrical synaptic transmission, the field of electrical synapses in mammalian systems may appear to have emerged suddenly at the beginning of this century, with the subsequent pace of progress in the area being nothing short of astonishing. Consequently, because electrical synapses are now unambiguously recognized to constitute a vital component in mammalian brain circuitry, it would be appropriate for those outside our field to ask why recognition of their importance and widespread distribution did not occur much earlier, and what factors contributed to this apparently abrupt transformation in knowledge. This is perhaps best answered by our initial consideration of two points in this review. First is the evolution in understanding of electrical synapses in invertebrates and non-mammalian vertebrates beginning mid-way through the 20th century, as contrasted with the more convoluted history surrounding investigations of those synapses in mammals, beginning shortly thereafter. Second is the confluence of multiple discoveries and technical advances that enabled major leaps in understanding and ultimately general acceptance of the critical role of electrical synapses in the mammalian CNS.

Also covered in this review are overlapping studies that implicate roles for electrical synapses in the high-speed neuronal network oscillatory activities that underlie the intricate processes of human consciousness, learning and memory, fine motor control, and complex information processing. Scores of investigations not only repeatedly confirmed earlier observations of neuronal gap junctions in various CNS areas and at different developmental stages, but they also revealed numerous previously unsuspected regions where electrical synapses occur. In particular, studies have for the first time exposed the high density that neuronal gap junctions occur in many of those locations, as visualized by immunofluorescence imaging of identified neuronal connexins. In addition, these investigations established the remarkable diversity of electrical synapses in the mammalian CNS, including the disparate neuronal types that are coupled by these synapses, the distinct subcellular sites at which these synapses are deployed, the connexin proteins that form neuronal gap junctions, and the wide variety of ultrastructural configurations that these junctions exhibit. And in the two final components, we focus on a few key unresolved issues, including those recently appearing on the horizon. One of these concerns the many brain regions where electrical synapses are almost certain to occur based on the presence of neuronally expressed connexin proteins, but where these synapses have not yet been studied by electrophysiological or other approaches. Another is the increasing evidence for the presence of gap junctions at mammalian axon terminals in the CNS, forming morphologically-mixed (i.e., chemical plus electrical) synapses but where the functional contribution of the gap junction component of these abundant synapses remains an enigma.

2. Electrical synapses in non-mammalian vertebrates

Following on the heels of the debate during the first half of the last century regarding whether neuronal communication was mediated electrically vs. by neuronal release of diverse chemical mediators, and shortly after the mid-century conclusion of that debate in favor of neurotransmission by chemical neurotransmitters, reports began to reveal the occurrence of direct intercellular electrical transmission, at least between neurons in non-mammalian systems. The first evidence for the presence of electrical transmission was obtained at contacts between the giant axon and the giant motor fiber of the crayfish [1], and it was soon followed by evidence in fish [2–8] and birds [9], demonstrating the presence of electrical synaptic communication in vertebrates. Moreover, the ability to combine electrophysiological analysis with ultrastructural imaging led to the identification of areas of close apposition between neurons and the discovery of gap junctions, the intercellular structures that underlie electrical transmission. Thus, studies in fish were seminal in establishing the basic properties and structural basis of electrical transmission in vertebrates, including the role of electrical synapses in promoting synchronized activity, and later providing evidence for the plasticity and diverse molecular composition of the constituent gap junctions (reviewed in [10]).

Many of the examples in which electrical transmission was observed in fish occurred at contacts in which gap junctions were associated with chemical synapses. The most studied of this synaptic configuration was the large myelinated club endings on the goldfish Mauthner cell [11]. At these large synapses, transmission is simultaneously supported by both chemical and electrical means [12,13], the coexistence of which greatly contributed to the identification of the presence and structural bases of electrical transmission in vertebrates [4,5]. These contacts later contributed to the description of novel plastic properties and exposed close interactions between electrical and chemical synapses (see below). Besides goldfish and electric fish, functional evidence for the presence of mixed synapses was also observed in lamprey ([14–16] and other cold-blooded vertebrates [17–22]; reviewed in [23]). Interestingly, coincident with the description of mixed synapses in the goldfish Mauthner cell, Martin and Pilar [9] reported the presence of mixed synaptic transmission in the chick ciliary ganglion, an anatomically peculiar synaptic contact between a parasympathetic preganglionic cholinergic fiber and the cell body of a postganglionic cell. These findings suggested that such mixed synaptic configurations in warm-blooded animals could occur elsewhere, including in mammals. A decade later, mixed synaptic transmission was reported to occur between primary vestibular afferents in the rat [24] and other species, including primates and humans (reviewed in [25]), and increasing anatomical evidence suggested their widespread distribution in the mammalian brain (see below).

3. Mammalian neuronal gap junctions; pre-millennial perspectives

Early on, direct cell-to-cell electrical and ionic communication and, in particular, proposals for direct intercellular propagation of electrical action potentials [26] were correlated with the existence of newly-recognized intercellular junctions called “gap junctions” (aka “nexuses”) in diverse neuronal and non-neuronal tissues [26–29]. The role of gap junctions in intercellular electrical communications was further confirmed in vitro by the de novo formation of gap junction-like close membrane appositions between pre-fusion skeletal myoblasts within seconds of the onset of electrical coupling [30] and by the subsequent freeze-fracture confirmation of abundant gap junctions between adjacent pre-fusion myoblasts in vivo [31]. Now, with electrical synapses as secure participants in the process of mammalian neuronal communication, it is perhaps less appreciated that the relatively recent work documenting the existence, abundance, functionality, and ultrastructural diversity of these synapses was preceded by a considerable body of literature suggesting the presence, if not the abundance, of these synapses in mammalian systems. This included more than 50 early ultrastructural, dye-coupling, and electrophysiological reports of neuronal gap junctions and electrical synapses in various areas of adult mammalian CNS published in the 1960’s [32], 1970’s [24,25,33–50], 1980’s [51–68], and 1990’s [69–75]; reviewed in 2000 [76]).

As discussed in reviews contemporaneous with the early reports [77–80], a number of factors contributed to the early general ambivalence surrounding the functional relevance of electrical synapses in mammals:

1. Ultrastructural factors

Neuronal gap junctions in mammalian CNS were difficult to find by thin-section electron microscopy (EM), which required optimal tissue fixation and staining, and much higher magnifications than used to find chemical synapses. Many more hours of microscope time than usually used for analyses of the much wider variety of excitatory, inhibitory and modulatory chemical synapses was necessary, and time-consuming goniometric tilting) analyses was required to obtain the requisite optimum viewing angles that allowed convincing visualization of the tell-tale close heptalaminar structures of gap junctions. The appearance of these structures (e.g., pentalaminar or septalaminar) depended on the chemical fixatives and stains used – potassium permanganate, osmium tetroxide alone, glutaraldehyde/osmium tetroxide fixation [81], with or without aqueous uranyl acetate post-stain [82]) to define gap junctions in thin sections [41,46,54,83]. The few neuronal gap junctions that had been found were relatively large (often >0.5 μm), leading to the idea that gap junctions/electrical synapses in mammals were equally large as those in lower vertebrates; and where these large gap junctions were found in mammalian brain, they were proposed to represent an evolutionary vestige remaining from “when we were fish”. Consequently, the much more abundant but much smaller gap junctions subsequently found in mammalian CNS [73,84] did not conform with earlier functional perspectives, in part, because the intercellular transmission capabilities of very small gap junctions were not consistent with the then-current ideas that regarded gap junctions as devices that serve primarily for rapid and efficient intercellular propagation of action potentials [27–29,85].

2. Synapse complexity and flexibility

Because electrical synapses were already known to occur widely in non-mammalian vertebrates, they initially were considered evolutionarily primitive, and perhaps not suited for the more sophisticated computations afforded by the diversity and flexibility of chemical synapses. Voicing a then common concept, Shepherd [86] proposed that the apparent absence of gap junctions in most areas of the CNS of higher vertebrates “could reflect a mechanism to increase the metabolic and functional independence of neurons, in order to permit more complex information processing” (emphasis added). This concept of gap junctions as sites for high-efficiency electrical coupling for direct relay of action potentials appeared to account for the reported restriction of gap junctions to “primitive” areas of the mammalian brain [24,32–35] and spinal cord [87,88], wherein propagated electrical activity was proposed to exist for synchronization of nerve activity in networks responsible for stereotyped motor behaviors as occurs for example, in direct conduction of sensory action potentials into the Mauthner cells that then initiate the “tail-flip” escape response, and in motoneurons controlling ocular movements in fish [8]. Thus, in those early days, propagation and synchronization of action potentials was the only electrical function that was widely recognized for neuronal gap junctions.

3. Technical challenges to addressing function

Except in ideal test systems, such as the locations where large gap junctions were found in lower vertebrates [3–6,89], early electrophysiological approaches to studies of electrical synapses in more complex systems were technically challenging; and only a few sites in mammalian brain lent themselves easily to even indirect detection of electrical coupling [24,35,40,41,44]. Even in mammalian CNS regions having strong neuronal coupling, this technical challenge was compounded by the absence of specific and robust pharmacological agents that could be used to manipulate or perturb functions of electrical synapses. Further, studies that did provide evidence for neuronal gap junctions by dye-transfer between neurons following injection of single neurons in tissue slices suffered criticisms that transfer of dye might have been artefactual, resulting from unrecognized impalement of multiple cells (the “shish kabob effect” [90]). Thus, technical limitations led to a paucity in functional correlates of electrical synapses in mammalian systems, which diminished enthusiasm for studies of these synapses.

4. Speed advantage of electrical transmission

A more subtle point related to the comparative speed advantage of electrical vs. chemical synaptic transmission is that the speed of chemical transmission was known to be temperature dependent, whereas transmission speed of electrical synapses was thought to be essentially independent of temperature. In cold blooded species, electrical synapses therefore were thought to provide an advantage, especially in sensory and motor systems, where speed of synaptic transmission is essential, as in the well-documented escape response in fish (reviewed in [91]). Indeed, in non-mammalian vertebrates, it was widely presumed that likely sites within neuronal networks in which to find electrical synapses were those where speed of transmission confers obvious survival advantages [92], but it should be noted that equivalent examination of other CNS areas in the same species were not conducted to determine whether they, too, contained gap junctions -- of any size. Instead, recent studies revealed abundant electrical synapses throughout goldfish brain [93]. Nevertheless, in early studies, such sites in mammals that were presumed to require rapid propagation of action potentials were less obvious, so much so that arguments were made that warm-blooded animals had abandoned or greatly reduced their reliance on fast electrical synapses. Even though all of these considerations fueled doubt about the importance of electrical transmission in mammals, it was repeatedly emphasized by Bennett that speed difference in electrical vs. chemical transmission can be minimal in warm blooded animals [78–80,94]. Thus, at mammalian body temperature, synaptic delay times in the two modes can be very nearly the same. Gap junctions, particularly the small gap junctions now documented to occur abundantly between mammalian neurons [73,84,95,96], may subserve as-yet-unidentified electrical, ionic, or metabolic functions [97] other than propagation of action potentials.

5. Electrical vs. chemical transmission

Perhaps because electrical transmission had been debated since early in the last century as a serious contender for mediation of neuronal communication, initial demonstrations of its occurrence in lower vertebrates and invertebrates were met with relatively little resistance and quickly accepted. This was in contrast to mammalian systems, where concepts regarding electrical synapses had a more prolonged emergence, beginning at a time when their potential roles needed to be considered against a slew of already-well-entrenched ideas and concepts surrounding chemical transmission.

6. Neuronal gap junctions during CNS development in mammals

A wealth of evidence indicating that electrical synapses are widely expressed during early stages of mammalian brain development became available in the early-mid nineties, and those observations included structures such as the neo-cortex [98–100], retina [101], and spinal cord [102]. Early gap junction connections were believed to create functional compartments and determine early network connectivity [98–100]; and coupling, often at the limit of detectability [102], was extrapolated to disappear (but not explicitly shown to disappear) as brain and spinal cord development progressed [102,103]. These observations provided unambiguous evidence for the presence and functional relevance of electrical synapses in mammalian brain development, with emphasis placed on relevance in immature systems and less so in adult CNS, where tools did not then exist that allowed equivalent analyses in adult brain and spinal cord slices (cf. [51]). By the turn of the new millennium, however, studies of electrical synapses in developing neural systems helped pave the way to the recognition that these synapses persist in vast areas of adult brain, particularly those gap junctions between inhibitory interneurons [58,104,105], which are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system.

For some of us, it was difficult to imagine at that time that the above cited bulk of early data on neuronal gap junctions in mammals did not have more profound implications; hence the impetus and dogged determination to study them with the then-available approaches. Perhaps better said is a quote from an early review by Bennett [77], where in considering favorably the value of electrical synapses vs. the then-current bias regarding the primacy of chemical transmission, in biasing his comparisons of electrical vs. chemical transmission to include only what were at that time physiologically demonstrated cases, he stated “This bias is introduced in order to confront the prejudices of those who regard electrical mediation as beneath the lofty mental processes of higher animals”. We conclude from the foregoing that, prior to about 1998, there was already sufficient evidence to seriously consider potential roles for electrical synapses in the mammalian CNS, with clear examples in the retina and inferior olive; but cautious interpretation, mixed with healthy skepticism and a modicum of bias against these synapses, prevailed in the absence of knowledge surrounding the biochemical underpinnings, abundance, and functional/electrophysiological manifestations of mammalian neuronal gap junctions, all of which came to light in close temporal succession with the technical and conceptual advances described below.

4. Transformative surge in understanding

By the last decade of the last century, a number of developments occurring in multiple disciplines led to a surge of reports that revitalized efforts to delve broadly and deeply into what would eventually become understanding of the occurrence, diverse types, wide-spread distribution, and functional roles of electrical synapses in mammalian brain and spinal cord. The evolution of events leading up to and beyond the renaissance that occurred at the turn of the century is illustrated in Figure 1. These developments included:

Fig. 1. Time line of significant technical advances and discoveries regarding electrical synapses in vertebrate species.

The blue overlay is a graphical representation of the previous 2632 publications that have investigated electrical synapses by a diversity of approaches in a variety of invertebrate and vertebrate species, with average number of publications per year for each decade indicated by numbered blue dots on the left margin. The center column indicates years from the point electrical synapses were discovered to the present. The left side lists the discovery dates for all mammalian connexins, with the first neuronal connexin identified towards the end of the 1990’s. The right side indicates landmark discoveries regarding the structure, function, and connexin composition of neuronal gap junctions and the development of methods used to study electrical synapses. Note the dense concentration of significant event around the turn of the century.

1. Discovery of Cx36

Among the family of 20 connexin protein members in mammals, connexin36 (Cx36), the 14th connexin to be discovered in 1998 [106,107] (1998) (Fig. 1), was the first found unequivocally to be expressed in multiple types of neurons in retina, brain, and spinal cord [84,108], strongly suggesting the presence of electrical synapses in widespread regions of the CNS. Cx36 protein was then quickly detected in ultrastructurally-defined gap junctions in retinal and spinal cord neurons [109–111]. Of note is that mRNA for Cx35, the fish ortholog of mammalian Cx36, was identified two years earlier in skate neurons [112], but Cx35 and Cx34.7 proteins were not immunocytochemically localized to neurons until 2003–2004 [113,114]. The relatively late discovery of Cx36 was much to the consternation of those of us seeking to study connexins localized at neuronal gap junctions, having examined its thirteen predecessors for such localization. Further, many other connexins, either based on detection of their mRNAs or their proteins, had (erroneously) been ascribed to neurons, including Cx26 [115], Cx32 [115–121], Cx47 [122], or a combination of Cx26, Cx37, Cx40, Cx43 [123–125]; but none of those connexin proteins were confirmed to be present by their detection in ultrastructurally-defined gap junctions [109–111] that simultaneously were found to contain Cx36 (with or without Cx45). Detection of connexin mRNAs without detection of the corresponding protein was later proposed, but not as yet demonstrated, to result from active suppression of translation of specific mRNAs into protein by newly-discovered micro interfering RNA (miRNA) mechanisms present in mammalian CNS neurons vs. glia ([126,127], as discussed in [128].

Subsequently, mRNAs for at least two more connexins, Cx45 and Cx57, were found to be expressed in neurons [129–135], and Cx45 was quickly documented to occur in ultrastructurally-defined gap junctions [136]. More recently, Cx57 and Cx50 immunofluorescence was localized to discrete puncta in the outer plexiform layer of rabbit and mouse retina [137–140] and localized to putative gap junctions in thin sections examined by TEM [138,140]. To date, neither of these connexin proteins has been documented in other brain regions. We have also found Cx57 in a few ultrastructurally-defined gap junctions in the outer plexiform layer of rat retina (Rash and Nagy, unpublished observations.) Likewise, lacZ reporter expression systems indicate that Cx30.2 may also be expressed in neurons throughout the brain and spinal cord [141], including in retinal ganglion cells [142], but remains to be confirmed by demonstration of Cx30.2 protein expression. Nevertheless, to date, Cx36 remains the most abundantly detected neuronal connexin protein in mammals.

The discovery of Cx36 allowed the generation of antibodies against this protein, use of which provided all of the powerful approaches that antibodies afford. In particular, visualization of Cx36 localization by immunofluorescence is well-correlated with its localization in gap junctions at the ultrastructural level [84,114] (Fig. 2), at least in vivo [95,96,128,137]. This is a fortuitous feature arising from immunofluorescence labeling for Cx36 exclusively at gap junctions, with its other potential subcellular and intracellular sites (i.e., rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, or cytoplasmic transport vesicles) either remaining masked or below the limit of fluorescence detectability by all anti-Cx36 antibodies that we have tested [138,143,144]. Such sites of gap junctions are illustrated by punctate immunofluorescence labeling of Cx36 in the olfactory bulb (Fig. 3A–C). Where visualization of marker proteins in neurons that express Cx36 is possible, labeling of Cx36 appears as Cx36-puncta distributed on neuronal somata and dendrites, as shown in cerebral cortex (Fig. 3D, striatum (Fig 3E), arcuate nucleus (Fig. 3F) and sexually dimorphic motor nuclei in spinal cord (Fig. 3G,H). Thus, visualization of Cx36 immunofluorescent puncta along neuronal surfaces provides a powerful tool for light microscopic identification of Cx36-containing neuronal gap junctions above a certain minimal size, represented roughly by >30–50 connexons, which corresponds to >70% of gap junctions in both retina [84] and spinal cord [73], thereby revealing their quantitative cellular and subcellular localization over large areas of the CNS [84,95,96,128,136–138,143–148]. It is highly likely that other sites with Cx36 puncta contain bona fide gap junctions, and will reveal functional correlates of both electrical and tracer coupling.

Fig. 2. Correlation of immunofluorescence and FRIL methods used to identify, quantify, map, and immunocytochemically characterize the wide variety of Cx36-containing gap junctions in adult rat retina.

A: Confocal image showing Cx36-puncta (green) vs. Nissl stained (red) neurons in a full-thickness section of rat retina. B: Correlative FRIL image showing exact locations of photomapped immunogold-labeled gap junctions. Numbered red triangles = locations of string gap junctions (all in sublaminae S2 and S1). Numbered blue circles = plaque gap junctions (in S2–S5). C: Higher magnification of boxed area in B. This crystalline plaque gap junction, mapped to sublamina S4, contains ca. 300 connexons that were immunogold double-labeled for Cx36 by 6-nm and 18-nm gold beads. D: Small string gap junction, mapped to S2, contains ca. 30 connexons labeled by 18-nm gold beads. E: Tiny crystalline plaque gap junction mapped to S2; 11 connexons are labeled by a single 12-nm gold bead. Based on quantitative FRIL analysis [84] showing that virtually all string gap junctions (mostly <100 connexons) and many small plaque gap junctions were abundant in S2 of both rats and mice (where others had found few or no gap junctions), we calculated that conventional immunofluorescence imaging had not revealed gap junctions smaller than ca. 100 connexons, which comprise the majority of gap junctions in retina, particularly in S1 and S2. F–G: For correlation, we compared immunofluorescence imaging protocols in which photomultiplier gain was reduced to avoid autofluorescence “noise” in tissue sections (F), with images in which photomultiplier gain was set at increased (optimum) gain in the same 8-μm section of retina (G). In F, relatively few puncta were detected in sublamina S2, where FRIL had revealed a high density of string and miniature plaque gap junctions (<100 connexons). With photomultiplier gain increased, many additional puncta were detected in the same area of S2 (G; circles), but without significantly increasing background autofluorescence. In contrast, the number of puncta visible in ON sublamina S4 (F; square) (where small gap junctions were rare by FRIL) was only slightly increased (G; square box), thereby allowing the first semi-quantitative immunofluorescence detection of this new class of abundant gap junctions containing 30–100 connexons. (Those smaller than 30 connexons remain undetectable by immunofluorescence in tissue slices.) F–G may be viewed as a stereo pair to visualize the 3-D distribution of small to large puncta in the various sublaminae. Offset arrows at C reveal gap junctions at top and bottom of section. RPE = retinal pigment epithelium; OS and IS = outer and inner segments of rods and cones; ONL = outer nuclear layer; OPL = outer plexiform layer; INL = inner nuclear layer; IPL = inner plexiform layer; GCL = ganglion cell layer; Ax = axons on the anterior surface of the retina. Numbers at left margins indicate approximate locations of sublaminae S1–S5. All images modified from [84], with permission. Calibration bars in all FRIL images are 0.1 μm unless otherwise indicated.

Fig. 3. Immunofluorescence labeling of Cx36 in various CNS regions of adult mouse and rat.

A: Main olfactory bulb of mouse, showing overview of a fluorescence Nissl-stained whole transverse section of the olfactory bulb. B,C: Higher magnification images showing labeling of Cx36 in an area (B) of the mitral cell layer (MCL) indicated by the boxed region to the right in A, and labeling of Cx36 in an area (C) of the glomerular cell layer (GCL) shown by the boxed region to the left in A. Detection of Cx36 appears exclusively punctate in both the mitral cell layer and glomeruli, which correspond to sites of heavily-concentrated neuronal gap junctions. D–F: Double immunofluorescence labeling for Cx36 and parvalbumin (PV) in the cerebral cortex (D) and the striatum (E), and double labelling for Cx36 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (F), showing PV-positive and TH-positive neurons (arrowheads) with Cx36-puncta distributed on their somata and/or processes (arrows). G,H: Double immunofluorescence labeling for Cx36 and the motoneuron marker peripherin, showing closely packed peripherin-positive motoneurons in the sexually dimorphic dorsomedial nucleus (DMN) (G, arrows) in a horizontal section of the lumbosacral region of rat spinal cord, with Cx36-puncta surrounding the motoneuronal somata and localized along motoneuron dendrites. Higher magnification shows peripherin-positive motoneurons (H, arrowheads) displaying Cx36-puncta at their somatic appositions (H, arrows).

2. Development of Cx36 null mice

The identification of Cx36 as a major neuronal connexin led to the generation of Cx36 null mice and the revelation of functional deficits in various neural systems of these mice, including visual, motor and memory impairments [149–156], helping considerably to expose the functional contributions of electrical synapses in mammalian neuronal networks. Some of the deficits found in these mice are further indicated in section 5.1 below.

3. Development and application of FRIL

Anatomically, difficulties imposed in the identification, documentation, and quantification of neuronal gap junctions by thin-section EM and by conventional freeze fracture were substantially surmounted by the advent of novel approaches to ultrastructural detection and characterization of neuronal gap junctions and their connexin constituents. These included the development of freeze-fracture replica immunogold labeling (FRIL), first introduced as SDS-FRL [157,158], and latter improved for use in complex CNS neuropil by combining SDS-FRL with “confocal grid-mapped freeze fracture” as “FRIL” [159]. The term FRIL was coined by Gruijters a decade earlier [160], and has precedence. More recent developments have included “matched-double-replica FRIL” (MDR-FRIL) [93,136], specific applications of which are described below. This approach allowed high-resolution, semi-quantitative analyses of symmetric vs. asymmetric connexin labeling in matching apposed hemiplaques of individual ultrastructurally-visualized gap junctions throughout the CNS. In contrast to thin-section EM, searches for neuronal gap junctions was facilitated by traditional freeze fracture because the fracture plane exposed much broader areas of tissue and revealed defining features of gap junctions in readily identifiable cell types [38,73,161]. Additional to the advantages of conventional freeze fracture, FRIL allows immunogold labeling and examination of connexins at ultrastructurally-identified gap junctions in equally broad expanses of tissue (Fig. 4). Moreover, the larger immunogold beads (20- and 30-nm) served as highly-visible “flags” that were readily detected at much lower magnifications than used when searching for gap junctions by conventional freeze fracture, and hence allowed rapid examination of greater tissue areas. Thus, the rapid advancement that FRIL provided for studies of electrical synapses is that many-fold more neuronal gap junctions were found by FRIL (now >4000) than by all previous ultrastructural studies in mammals combined (op cit), with the additional advantage that their constituent connexins were identified [84,109,128], simultaneously revealing the presence of Cx36 [110,111,162] and/or Cx45 [136] and absence of Cx26, Cx30, Cx32, and Cx43 [110,111].

Fig. 4. FRIL images of a Cx36 immunogold-labeled reticular gap junction on neuronal soma in adult rat suprachiasmatic nucleus.

A: Neuron cell body, revealing its nucleus (N, with abundant nuclear pores), cross-fractured cytoplasm (*), and its somatic plasma membrane containing an immunogold-labeled gap junction (inscribed box). Note the complete absence of “background” labeling. Double-ended arrow traces continuity of cytoplasm, as maintained by the carbon support film, even in the absence of an electron-dense platinum coating. B: High magnification of the boxed area in A, showing a distinctive reticular gap junction, characterized by the presence of connexon-free voids within the junction (modified from Fig. 3 in [96] with permission). Both images originally published as stereo pairs to facilitate 3-D analysis.)

4. Dual cell recording under direct visualization

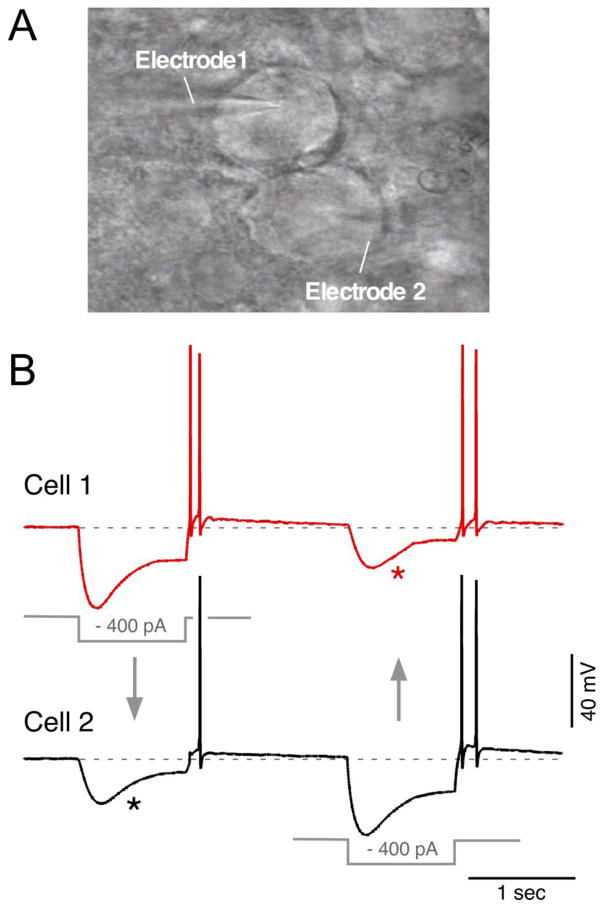

A greater sophistication of electrophysiological analyses was achieved in the late nineties with the advent of dual cell recording [163–165] (Fig. 5), which was enabled by the development of patch-clamp electrodes (reviewed in [166]) that allowed simultaneous recordings of neighboring cells, thereby increasing the probability of detecting electrical coupling. Dual whole-cell recording under visualized conditions, permitted recording from neighboring neurons, at which the incidence of coupling is much higher [164], thus overcoming difficulties arising from the pattern of connectivity that is unknown to the experimenters when doing blind simultaneous recording from two cells in morphologically complex tissue [167]. Moreover, recordings from electrically-coupled pairs was faciitated by the generation of transgenic mice at which cell-specific proteins are labeled with fluorescent proteins (i.e., parvalbunim) and transgenic mice with Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) expression of EGFP linked to Cx36 promoter (Cx36-BC-EGFP). This rapid expansion of electrophysiological technology provided strong support for functional electrical coupling of CNS neurons at a time when morphological evidence was mounting for wider and wider occurrence of neuronal gap junctions and for widespread expression of Cx36 in their gap junctions.

Fig. 5. Visualized paired recordings of electrically coupled cells in the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus (MesV).

A: Infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) image of two contiguous MesV neurons during a simultaneous whole-cell recording (electrode 1 and electrode 2). B: Simultaneous recordings from a pair of strongly coupled MesV neurons. Voltage responses to 200 ms hyperpolarizing ( 400 pA) current pulses injected either in cell 1 (red trace) or cell 2 (black trace) evoke corresponding coupling potentials (asterisks). Rebound depolarization after hyperpolarizing pulses causes cell firing. Unpublished image and recordings kindly provided by S. Curti (UdelaR, Montevideo, Uruguay).

5. New tracer molecules

While dual cell recording may still remain challenging, an alternative means for analysis of neuronal gap junction coupling is through intracellular dye- or tracer-injection, and subsequent visualization of tracer transferred between cells via gap junctions. Such transfer between neurons in mammalian CNS first utilized the dye Lucifer Yellow (LY; mw = 444) [55,56,69]. However, its use and use of other higher molecular weight dyes was soon contraindicated with emerging data showing that most mammalian electrical synapses are composed of Cx36, and by findings that LY is poorly permeable through Cx36-containing gap junction channels [152,168]). The development and use of smaller tracers, including Neurobiotin (mw = 287) and biocytin (mw = 372) [72], for visualization of neuronal coupling and, in particular, demonstration of large networks of coupled neurons (Fig. 6), represented another major improvement and addition to the arsenal of approaches available to tackle questions surrounding mammalian electrical synapses. It is noteworthy, nevertheless, that early demonstrations of LY transfer between neurons suggested the possible presence of neuronal gap junctions composed of a connexin (other than Cx36) that forms channels that are at least weakly permeable to this dye. It should also be noted that among some neurons known to be electrically coupled by Cx36-containing neuronal gap junctions, such as preganglionic sympathetic neurons in the spinal cord [169,170] and neocortical interneurons [164], tracer transfer, even with the above lower molecular weight tracers, was not detectable or was barely detectable above fluorescence noise. This was possibly due to the very small size and low rate of flux through the otherwise abundant gap junctions associated with these neurons, as determined by their display of a high concentration of albeit very small Cx36-puncta (Nagy unpublished observations).

Fig. 6. Tracer coupling reveals the organization of functional compartments formed by electrical synapses.

A: Cluster of neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus following intracellular injection of Neurobiotin (0.5% in the internal solution) during a whole cell recording. While the injected cells appear completely filled and labeled by Neurobiotin, only the cell bodies and proximal process are Neurobiotin-positive in the coupled cells. B: Dye coupling reveals that clusters can be spherical or elongated (compare the extension and spread of clusters), suggesting differences in coupling architecture. These clusters project to different regions of the ventrobasal (VB) and posterior medial (POm) nuclei of the thalamus. Panels A and B are modified from Lee et al, 2014 [253], with permission.

6. More effective gap junction blockers

A wider range of drugs with gap junction actions became available, and their specificity and off-targets effects were better characterized. These included the quinine derivative, mefloquine [171–173], which more specifically blocked Cx36-containing gap junctions. Although less specific, an additional gap junction blocker, meclofenamic acid, also has been useful in the study of electrical synapses [174,175].

7. Spikelets correlated with gap junctions

Transmission of spikes (action potentials) through electrical synapses evokes corresponding coupling potentials in a postsynaptic cell, roughly resembling the time course of the presynaptic action potential (see below). These so called “spikelets” (or “fast pre-potentials”) can be spontaneously observed in electrically-coupled networks, indicating the occurrence of action potentials (spikes) in cells that are presynaptic to the recorded cell. However, spikelets were initially proposed to represent dendritic spikes [176] (i.e., active dendritic signals), casting doubts on whether spikelets were indicative of the presence of electrical synapses, as had been proposed [52]. More recently, paired recordings [163–165,177–179] confirmed initial observations [52] indicating that indeed spikelets often represent the intercellular propagation of presynaptic action potentials. Moreover, the detection of spikelets was found to be correlated with dye coupling [179] and with immunolabeling for neuronal connexins [180]. Spikelets have also been observed during in-vivo intracellular recordings [181,182]. The detection of spikelets as indicative of the presence of electrical synapses should, however, be taken with caution, as dendritic spikes were also reported to occur in many cell types [183–185], and the presence of gap junctions should be independently confirmed using additional approaches such as freeze fracture, dye coupling, immunolabeling, and/or paired simultaneous recordings.

5. Mammalian electrical synapses; post-millennial perspectives

5.1. Functional impact of electrical synapses

Application of the newly-derived knowledge and innovations described above, together with an expanded effort of neuroscientists venturing into the field of electrical synaptic transmission, led to a surge of reports indicating both the prevalence and functional importance of electrical synapses in many diverse regions of the mammalian CNS, especially in inhibitory interneurons [104,186], which are widely distributed in many CNS structures. Most enlightening were revelations that electrical synapses participated in mediating neuronal electrical activities and physiological processes that were already well-established to be fundamental properties of neural circuitry, including synchronization of neuronal network activity [150–152]. A short but non-exhaustive list of structures in the mammalian CNS where evidence has been gathered for the functional importance of electrical synapses includes: 1. Retina is the CNS structure with the highest diversity of neuronal connexins, and where electrical synapses and their regulation are known to underlie a variety of functional processes [187]. For example, electrical synapses, often at glutamatergic mixed synapses, are essential in the transmission and modulation of rod and cone signals through multiple pathways, ultimately to retinal ganglion cells, and where transmission of these signals is impaired in Cx36 null mice [188,189]; 2. Olfactory bulb, where electrical synapses formed primarily by Cx36 [128] are necessary for rapid spike synchronization of mitral cell activity [190]; 3. Cerebral cortex, where electrical coupling between GABAergic interneurons is proposed to generate synchronous activity in interneuronal networks and in neocortical pyramidal cells [163,164,186,191–194]; 4. Hippocampus, where electrical synapses promote synchronous activity among inhibitory interneurons, enabling synchronous high-frequency γ-oscillations in pyramidal cells, and these γ-oscillations are disrupted in Cx36 null mice [105,195–200]; 5. Reticular thalamic nucleus, where Cx36-containing gap junctions promote synchronization of burst-firing [201] and are capable of supporting spindle frequency rhythms among small clusters of neurons [201,202]; 6. Suprachiasmatic nucleus, where Cx36-containing neuronal gap junctions [96] are reportedly required for normal circadian behavior and where deficits in circadian rhythms may arise from loss of these gap junctions in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in Cx36 null mice [203,204]; 7. Hypothalamus, where electrical synapses linking magnocellular neurons are thought to enable synchronization of burst firing for pulsatile oxytocin release [67,205–207]; 8. Inferior olive, where electrical synapses [41] containing Cx36 [208–211] provide for subthreshold network oscillations and for synchronous and rhythmic activation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers, providing for temporal precision of movement, which is impaired in Cx36 null mice and is also impaired after manipulations of junctional coupling between inferior olivary neurons [209–216]. 9. Brainstem, where electrical synapses in respiratory nuclei contribute to inspiratory-phase synchronous activity and modulation of respiratory frequency of coupled neurons [217–220]; 10. Spinal cord motor systems, where electrical synapses between interneurons provide synchronization of subthreshold potentials and rhythmic firing that is in phase with ventral root motor output, suggesting a contribution of these synapses to operation of the locomotor central pattern generator [221]. 11. Spinal cord sensory systems, where the well-known phenomenon of primary afferent presynaptic inhibition was found to be impaired in Cx36 null mice [146], indicating that electrical synapses play an essential role somewhere in the circuitry governing this inhibition. 12. Gastrointestinal system, where enteric neurons of the myenteric plexus were found to be linked by Cx36-containing gap junctions, and where Cx36 null mice displayed physiological deficits in regulation of gut smooth-muscle contractility [222].

In the above examples, promotion of synchronous activity is one recurring feature attributed to the activity of electrical synapses. Transmission at electrical synapses is usually bidirectional, and therefore changes in the membrane potential of cells within an electrically-coupled compartment are presumably shared with all the partners of the network [151,223]. This includes not only action potentials but also subthreshold responses, such as synaptic potentials [224] and spontaneous oscillations [210]. Such arrangement allows electrical synapses to serve as coincidence detectors [179,225,226], because temporally-correlated changes in the membrane potential of some of the cells will be detected by the others. This occurs because electrical synapses allow electrical currents to leak to coupled cells, which markedly reduce cellular excitability. However, this effect can be transiently cancelled if both cells are simultaneously depolarized. This “coincidence detection” property enormously impacts the integrative properties of circuits and can lead to coordinated cellular activity.

Another salient property of electrical synapses in mammals is that they behave as low pass filters [151]. This is not a property of the gap junction per se, but results from the interaction of the passive properties of the coupled cells. The strength of electrical transmission is determined by the conductance of the gap junction and the resistance and time constant of the coupled cells [227]. Brief, high frequency-containing signals such as spikes are greatly attenuated, whereas longer lasting, low frequency-containing signals are less attenuated by the time constant of the postsynaptic cell. One of the functional consequences of low-pass filtering is that the coupling evoked by presynaptic spikes containing a long-lasting pronounced after-hyperpolarization will be predominantly hyperpolarizing and thus inhibitory, as the after-hyperpolarization will be substantially less attenuated than the spike [151,180,228]. Interestingly, this property was shown to lead to the desynchronization of the cerebellar Golgi cell network [180], indicating that electrical synapses can endow networks with more complex properties.

Finally, electrical synapses have been reported to be highly plastic and capable of modifying their coupling strength under various physiological conditions [229–233], and these changes could quickly reconfigure networks, such as occurs in the retina [187]. Thus, altogether, these properties provide sophisticated computational capabilities to neuronal networks containing electrical synapses.

The efficiency with which electrical synapses promote synchronization of neuronal activity has led prominent investigators to suggest that “the presence of electrical synapses among a population of neurons should prompt us to ask when and why they need to synchronize their activity” [234]. In this context, an emerging principle is that synchronous neuronal activity enables synchronous oscillations (e.g., theta 4–12 Hz, gamma 30–80 Hz, and high-frequency 200 Hz oscillations) among ensembles of neurons, where these oscillations temporally correlate firing patterns in disparate networks. It has been stated [235–238] that “brain oscillations are generated in almost every part of the brain”, that “network oscillations may take part in representing information, regulate the flow of information in neural circuits, and help store and retrieve information in synapses distributed throughout cortical networks”, and that “in primate brain there is growing evidence that oscillations are linked to behavior and cognitive tasks”. Further, “even the Holy Grail of cognitive neuroscience – consciousness – has been proposed to involve oscillations of coordinated neural activity in multiple brain areas” [239], as elaborated in several reviews [240,241]). Thus, electrical synapses, with their propensity to support synchronous neuronal activity, have emerged from relative obscurity in mammalian brain to now a place at center stage in contributing to the generation of network oscillations that are considered to be fundamental for information processing in the CNS. Indeed, it has been considered that “as more is learned, we may soon witness the emergence of the electrical synapse as an important element in textbook wiring diagrams of the vertebrate brain” [239]. And finally, it has been noted that “if one considers the experimental evidence indicating that connexins are important for neurophysiology, it is also likely that they may be involved in pathology” [152]. For example, mutation in the non-coding (regulatory) region of the gene for Cx36 has been linked to debilitating juvenile myoclonic epilepsy [242,243].

5.2. Anatomical distribution of electrical synapses

Although it is common to read in the literature that neuronal gap junctions are localized primarily to inhibitory GABAergic interneurons [68,104,105,186], this generalization belies the true diversity of neuronal systems in which these synapses occur. In fact, studies involving analyses of either electrical coupling, dye-coupling, localization of ultrastructurally-identified neuronal gap junctions, and/or immunofluorescence imaging of Cx36 have provided evidence for abundant electrical synapses (including morphologically-mixed synapses) interlinking excitatory neurons, including those with long-axon projections [25]. The best examples of these latter categories were the first systems in which mammalian electrical synapses were identified, namely between: 1. Excitatory glutamatergic inferior olivary cells [41], which project as climbing fibers to the cerebellum; and 2. Glutamatergic excitatory trigeminal mesencephalic primary afferent neurons [34,35], which innervate masseter muscles and periodontal ligaments. Other examples include: 3. Excitatory glutamatergic retinal ganglion cells [188,244], which have long centrally-projecting axons to several brain areas; 4. Excitatory glutamatergic olfactory mitral cells [245,246], which also have long centrally-projecting axons to multiple brain regions; 5. Excitatory glutamatergic cortical and hippocampal pyramidal cells [177,247], whose projections are numerous and extend into diverse regions of the brain; 6. Noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons [248], which have widespread projections throughout the brain; 7. Vestibular and cochlear primary afferents, which innervate the auditory complex and terminate in the central vestibular nucleus (see [143] and references therein) and cochlear nuclei ([249] and references therein); 8. Excitatory glutamatergic fusiform and inhibitory stellate interneurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus, where fusiform neurons are electrically coupled to stellate cells, and stellate cells are coupled amongst themselves in this nucleus [250]; 9. Cholinergic spinal preganglionic sympathetic neurons [169,170], which have long projections to diverse peripheral tissues; 10. Glutamatergic spinal myelinated primary sensory afferent neurons [144], whose cell bodies located in dorsal root ganglia have large-diameter fibers that innervate muscle spindles and terminate centrally on motoneurons in the spinal cord ventral horn; 11. Cholinergic sexually dimorphic motoneurons [87,120,147], which innervate sexually dimorphic perineal musculature; 12. Spinal unmyelinated primary afferent neurons [64,251,252], which are likely peptidergic, innervate skin, and terminate in the dorsal spinal cord.

Based on these diverse examples, it is almost certain that electrical coupling will be found to be a feature of additional non-GABAergic neuronal populations. Detailed studies of coupled GABAergic systems, however, have also reached a considerable level of sophistication [253,254]. Moreover, a novel combination of sequential confocal immunofluorescence mapping and TEM examination of the same contact areas revealed Cx36-containing gap junctions linking GABAergic interneurons in striatum [255] and cortex [256], with those studies providing novel quantitative insights into neuronal network connectivity.

5.3. Subcellular locations of diverse types of electrical synapses

Based on cumulative immunocytochemical, ultrastructural, and physiological data from diverse disciplines, it is now clear that in mammalian CNS: a) there are at least five anatomical and functional types of electrical synapses, b) each type of electrical synapse contains from one to several gap junctions, all of which are composed predominately of a single distinguishing type of connexin (i.e., Cx36, Cx45, or Cx57), c) each type of electrical synapse occurs at a specific subcellular location that is related to its primary function, and d) that there are specific targeting mechanisms for these neuronal connexins at each type of subcellular location, as well as for co-targeting of their accessory synaptic proteins (e.g., cell adhesion molecules, neurotransmitter receptors, synaptic vesicle proteins). These broadly-defined electrical synapse types include:

1. Purely electrical dendro-dendritic synapses [58,59,62,68,105,186,245,257–260]

So far, Cx36 is the only connexin localized at these purely electrical synapses [178,180,261] in various brain regions other than retina. In retina, purely electrical synapses formed by connexins Cx57 occur at dendro-dendritic contacts between horizontal cells in rabbit [139], whereas axo-axonic and axo-dendritic contacts between horizontal cells in mice are reportedly formed primarily by Cx50 [140]. Note, however, that either or both of these types of appositions have not been determined physiologically or ultrastructurally to be purely electrical vs. morphologically-mixed synapses.

2. Purely electrical somato-somatic synapses

As originally described in fish (relay cells in electric fish), electrical synapses have been shown to occur between the cell bodies of neurons, such as in the case of the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus [32,34,35,179].

3. Axo-axonic electrical synapses

Although these were originally reported in fish [6–8], there is substantial literature on the role of hypothesized axo-axonal gap junctions in high-frequency electrical network activity in rodents. Sharp-wave ripples (SWRs) occurring at a frequency of 100–250 Hz in the hippocampus are of particular importance because these oscillations are reported to be generated in axons [262], have high temporal and spatial coherence, and occur during experience-specific reactivation (“replay”) of sequences of neurons [263–265]. The mechanisms responsible for production of SWRs are not known, but experimental and modeling data predict their mediation by electrical synapses that have been proposed (but not yet documented) to link the axon initial segments (AIS) of principal cells in the hippocampus and in the cerebral cortex [266–270]. The AIS of hippocampal pyramidal cells are devoid of labeling for Cx36 (Nagy, unpublished observations), and SWRs apparently persist in Cx36 ko mice [195,197,271], yet the inference of gap junctions in the AIS presumably composed of some neuronal connexin other than Cx36 is supported by observations of dye-coupling between hippocampal pyramidal cells [266], elimination of SWRs by gap junction blockers [272], and observations that SWRs can occur in the absence of chemical synaptic transmission [266,270].

4. Excitatory “mixed” synapses

These are combined chemical plus electrical synapses [25,37,40,41] that are established, at the minimum, to link axon terminals with somata or dendrites (axo-somatic and axo-dendritic), where the gap junction component contains Cx36, as we have shown in rodent spinal cord [144,147,148], trigeminal motor nucleus [144,148], and lateral vestibular nucleus [143], and which so far are exclusively glutamatergic [137,143,273]. However, in the retina [136] and olfactory bulb [128], a few axo-somatic and axo-dendritic gap junctions also contain Cx45 [136] or a mixture of Cx36 and Cx45, the latter forming “bi-homotypic” gap junctions [136]. In the latter, MDR-FRIL (Fig. 7) revealed domains of Cx36 gold beads (10-nm) opposite domains of gold beads for Cx36, and domains of gold beads for Cx45 (5-nm) opposite domains of gold beads for Cx45, the combination not forming heterotypic (i.e., Cx36:Cx45 gap junctions) but instead, forming bi-homotypic (Cx36:Cx36 plus Cx45:Cx45) gap junctions in retina. Such MDR-FRIL mapping has not yet been conducted in olfactory bulb or in other locations co-expressing Cx36 and Cx45.

Fig. 7. Matched double-replica FRIL (MDR-FRIL) showing separate gap junctional domains labeled solely for Cx36 adjacent to domains labeled solely for Cx45.

The image shows a single gap junction viewed after capture of both its hemiplaques in apposing membranes, with one hemiplaque showing areas of particles (A, arrow) and pits (A, arrowhead) and the other in corresponding areas showing instead pits (B, arrowhead) and particles (B, arrow), separating the regions where the membrane fracture skips from one apposed membrane to the other (B, double arrowhead). This and six other matched gap junctions displayed separate domains of Cx36 localization in one hemiplaque opposite Cx36 localization in the apposed hemiplaque, and similarly, Cx45 localization in the same hemiplaque opposite labeling for Cx45 in the apposed hemiplaque. Combined with data from 60 other unmatched hemiplaques containing both Cx45 and Cx36, we concluded that most/all retinal neurons expressing Cx45 also express Cx36, with both connexins co-existing in both apposed hemiplaques. Thus in retina, these two connexins form bi-homotypic (Cx36:Cx36 + Cx45:Cx45) gap junctions [136], rather than forming heterotypic Cx36:Cx45 gap junctions, as previously proposed (references cited in [136]). (Modified from Fig. 6 in [136], with permission.)

5. “Reciprocal” (mirror) dendro-dendritic mixed synapses [83,128,159,190,274,275]

These have been proposed to form high-speed “reciprocal” (positive feedback or self-amplifying) oscillations, and so far have been found only at these glutamatergic appositions, which apparently contain only Cx36 [128].

Among the above configurations of gap junctions where Cx36 has been identified, it is noteworthy that, in at least mammalian systems, this connexin has been found so far to be engaged exclusively in homotypic gap junction channels, meaning that Cx36 on one side of a hemiplaque always couples with Cx36 in the apposing hemiplaque, and never to another connexin. Indeed, it was reported that Cx36 was non-permissive for coupling with nearly half of the other connexin family members that were tested for coupling permissiveness [276]. This extraordinary selectivity of Cx36 coupling only with itself distinguishes Cx36 and Cx36-containing neuronal gap junctions from other connexins that are found in a variety of other cell types. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, for example, each express three connexins, five of which engage in various combinations of heterotypic coupling, in both homologous (i.e., same cell type) and heterologous (i.e., different cell type) configurations. Notwithstanding assorted cellular factors that may determine different cell types that have capability to form gap junctions with each other, about which little is known, the lack of coupling permissiveness of Cx36 with other connexins may be required in part to prevent its coupling with, for example, the various glial connexins.

The above five synaptic configurations established so far may provide evidence for multiple mechanisms of regulation of electrical synapses in neuronal synaptic circuitry, but if so, most configurations are not yet characterized physiologically. It also should be noted that inhibitory mixed synapses formed by GABAergic axon terminals on neuronal somata and dendrites (axo-somatic and axo-dendritic) have been suggested, but evidence for the existence of inhibitory mixed synapses is considered tenuous because the single report [277] showing a gap junction at a putative inhibitory mixed synapse ostensibly labeled for GABAa receptors has not been confirmed by others, and the clump of gold beads denoting GABA receptors was present in an area of membrane E-face that did not exhibit clusters of intramembrane particles or pits, which are widely acknowledged as the freeze-fracture correlates of all transmembrane proteins.

5.4. Ultrastructural diversity of Cx36-containing gap junctions

Gap junctions have been almost universally described as “plaques” of tightly clustered intramembrane particles (“connexons”), either in regular hexagonal array (“crystalline”) or in irregular distributions (“non-crystalline”) (Fig. 8a). Early reports attempted to determine whether gap junctions with regular crystalline order were either the conductive or the non-conductive form, or whether one or the other of those two forms resulted from artifacts of chemical fixation ([278,279] and references therein). However, reports of unusual but rare “string” gap junctions in retina [38], and descriptions of gap junctions with dispersed connexons or with internal voids [38,280] (“lacey” or “reticular” gap junctions [84,96,281]) hinted at more diverse forms. With the advent of FRIL, with its capacity for finding large numbers of immunogold-labeled neuronal gap junctions (now >4000 FRIL-labeled mammalian neuronal gap junctions individually photographed by us), at least seven distinct gap junction morphologies based on connexon distributions are now recognized [84]: 1. crystalline plaques (Fig. 8A), ranging from a few connexons to a few thousand connexons, all in crystalline hexagonal array; 2. non-crystalline plaques (Fig. 8B), ranging from a few connexons to several thousand connexons in irregular, sometimes slightly dispersed array; 3. reticular gap junctions (Fig. 8C; also Fig. 4B), having from a few dozen to several hundred connexons, with one or more internal voids larger than 30 nm; 4. ribbon gap junctions (Fig. 8D), composed of one or more extended but centrally-connected or circular strips 2–4 connexons wide and up to 100 connexons long; 5. string gap junctions (Fig. 8E), consisting of a few to several hundred connexons arranged as rows of individual connexons (like beads on a string); 6. “meandering” gap junctions (Fig. 8F), consisting of a few to several dozen loosely-organized, non-crystalline connexons that sinuously wander over short distances; and 7. “cluster” gap junctions, consisting of several small, closely-spaced groups of connexons, with no obvious linkages between clusters. In addition, plaque gap junctions with greatly increased spacing between connexons have been reported in gap junctions of the outer plexiform layer in rabbits [280]. Whether these represent an eighth type of gap junction formed from a different connexin having more dispersed connexins (e.g., Cx50 or Cx57 [282]), species-specific differences, or other factor, remains unexplored. The functional relevance of these distinctive ultrastructural configurations are unknown, but the abundant string gap junctions in the inner plexiform layer normally occur only in the functionally-defined OFF lamina, primarily in sublamina S2 [84,161], as well as occasionally in the outer plexiform layer [280]. Although quantitative analysis of gap junction morphologies have been conducted primarily in retina [84], reticular gap junctions also have been reported linking hippocampal neurons [283] and neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus [96] (Fig. 4). Moreover, preliminary data suggest the inter-convertibility of plaque, ribbon, and string gap junctions, based on patterns and frequency of neuronal activity and on state of connexin phosphorylation [284], but such studies are in their infancy [285–287].

Fig. 8. Seven basic morphologies of neuronal gap junctions in retina and hippocampus immunogold labeled for Cx36.

A: Large-diameter crystalline plaque gap junction from ON lamina of adult rat retina (ca. 900 connexons); B: E-face image of small-diameter non-crystalline plaque gap junction in ON sublamina of rat retina (ca. 90 connexons immunogold labeled with two sizes of gold beads. C: Reticular gap junction from adult rat hippocampus. D: Large multi-strand ribbon gap junction (ca. 490 connexons; pink overlay) in the OFF sublamina of adult rat retina (S2) labeled for Cx36 with two sizes of gold beads. E. Portion of E-face image of large compound string gap junction in the OFF sublamina S2 (previously unpublished image). F: “Meandering” gap junction in rat hippocampus, consisting of 25 connexons labeled for Cx36 beneath their E-face pits. G: Dispersed clusters of connexons in adult rat hippocampus (unpublished image). (A and B, modified form Fig. 3 in [84]; C and F, modified from Fig. 11 in [273]), D, modified from Fig. 5A in [84]; all with permission.

6. Mixed synapses in mammalian brain

Shortly after or concomitant with demonstrations of neuronal gap junctions in the inferior olive and the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus of rat [32,35,40], ultrastructural investigations of mammalian brain convincingly revealed mixed chemical/electrical synapses [25] in regions corresponding anatomically to those in non-mammalian vertebrates, where mixed synapses were first found [4–7,22]. These and several more recently-identified areas at which immunolabeling for Cx36, in combination with the nerve terminal synaptic vesicle marker vesicular glutamate transporter-1 (vglut1), has been found at axon terminals in rat and/or mouse, presumably forming mixed synapses, include: 1. Lateral vestibular nucleus [24,25,33,44,54,143]; 2. Cochlear nucleus [54,249]; 3. Medial nucleus of the trapazoid body [249]; 4. Lateral superior olivary complex. [249]; 5. Hippocampus, specifically in the CA3 region of rat ventral hippocampus [138,273]; 6. Brainstem and spinal cord motoneurons [73,144,148], and 7. Retina [38,84,161,280].

In many of the above mammalian systems, there is a paucity of electrophysiological evidence that the gap junction component of those mixed synapses serves to mediate electrical transmission. Such evidence, albeit obtained by indirect means, has been reported in primary vestibular afferent fibers contacting vestibular neurons [24,39], and in mixed synapses formed by hippocampal mossy fibers [288,289]. This is in contrast to the extensive studies on electrical transmission by mixed synapses formed by, for example, eighth nerve afferents in goldfish (discussed above), as well as in other species, including toadfish [22], frog [19,290], lizard [291], and pigeon [292]. In contrast to studies in lower vertebrates, analysis of electrical transmission at mixed synapses is more challenging in mammalian systems, where synaptic delay of chemical vs. electrical mediation is less distinguishable due to the slower time constant of mammalian neurons that attenuate brief changes in membrane potential (low pass filtering effect). More detailed considerations of mixed synapses in mammalian CNS and their possible functional roles are discussed elsewhere [293].

7. Issues on the horizon

Early on, it was considered by some that the presence of neuronal gap junctions, as identified ultrastructurally or by immunofluorescence visualization of their connexin constituents, did not necessarily require that these junctions ever serve as functionally-active electrical synapses. The field has moved beyond such views, which should be held as no longer tenable because electrical coupling and/or dye-coupling between specific neurons has been found at many locations where there is evidence for gap junctions between those same neurons. At the current state of knowledge, it might be more prudent to suppose that where neuronal gap junctions occur, they are likely to have and will ultimately be found to have functional roles. Nevertheless, many outstanding issues remain, some of which are listed as follows.

1. Gap junction and connexin characterization required at identified sites of coupling

There are situations where electrical and/or dye-coupling between neurons has been demonstrated, but where there is an absence of evidence for gap junctions linking those coupled neurons. Examples of this, among others, include pyramidal cells in the cerebral cortex [247], pyramidal cells in the hippocampus [138,177], and dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [60,294]. A different version of this scenario occurs where neurons have been found to be electrically-coupled and to display gap junctions, but where the connexin constituent of those junctions have defied identification. Examples of this are the hypothalamic magnocellular nuclei, including neurons that express oxytocin or vasopressin in the supraoptic nucleus and paraventricular nucleus, where we have failed to detect Cx36 (Nagy, unpublished observations) or any other putative neuronal connexin.

2. Neuronal connexin compensation

A related problem concerns examination of electrical coupling in Cx36-null mice. In at least three brain areas where neurons are extensively coupled by gap junctions, the primary known constituent of which is Cx36, Cx36 null mice still exhibit residual electrical coupling. These include the reticular thalamic nucleus [253,295], inferior olivary nucleus [296], and the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus [179]. While compensation for the absence of Cx36 by another connexin in these areas is possible, we have failed to detect at least a dozen candidate connexins in the two latter regions of Cx36 null mice, including Cx45 and Cx57 (Nagy, unpublished observations). However, connexins may be present in fewer than 30–50 connexons, and therefore be functional but not detectable by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2F,G; modified from Fig. 10 in [84]). The nature and extent of the residual coupling and the identity of the connexin involved remains an important issue because the full scope of functional deficits examined in the Cx36 null mice might not be manifest if some degree of coupling compensation occurs. Moreover, it is not known whether the connexin that underlies the observed residual coupling in the Cx36 null mice is normally present in gap junctions between neurons in the above three systems and, if so, whether it contributes to coupling in wild-type mice.

3. Morphologically-mixed vs. functionally-mixed synapses

Morphologically-mixed synapses in mammals were first identified and characterized by Sotelo, Llinas, and coworkers at axon terminals on somata and dendrites [25,33]. Within the axon terminal, as identified by its content of abundant uniform-diameter synaptic vesicles, pre-synaptic “active zones”, and distinctive electron-dense postsynaptic densities (PSDs), the gap junction component was found to occur in close proximity to one or more specializations characteristic of chemical synapses, including electron-opaque active zones that in turn were in direct intercellular apposition to an electron-opaque PSD. In this “dyadic” arrangement (the classical morphologically-mixed synapse), depolarization or hyperpolarization of the postsynaptic cell is thought to influence, via the electrical synapse, the amount of neurotransmitter released during each axon terminal depolarization, as recently shown to occur after depolarization or hyperpolarization at other types of axon terminals [297]. Subsequent to the discovery of dyadic mixed synapses, a “‘triadic” arrangement, where an axon terminal forms a chemical synapse to one dendrite, which is separately coupled via a gap junction to a second, immediately adjacent dendrite, has been observed in multiple CNS locations (see Figs. 13–14 in [25]). In this first of several forms of “functionally-mixed” synapse, the gap junction linking to the second dendrite could allow depolarization/calcium influx into the second dendrite to activate “silent” AMPA receptors in the first (postsynaptic) dendrite, providing another potential type of regulatory circuit mechanism, especially during development wherein both electrical and silent glutamatergic synapses coexist [99,298,299]. Conversely, influx of Ca++ through postsynaptic NMDA glutamate receptors in the first dendrite may modulate electrical conductance of the nearby gap junction, potentially providing yet another type of regulatory mechanism [300–302].

Unfortunately, the word “functional” (as opposed to “non-functional”) has also been applied to mixed synapses (“functional mixed synapse”), in analogy to active vs. “silent synapses” [303], further confusing terminology. For the purposes of this review, the term “functionally-mixed” synapses applies only to several diverse triadic arrangements in which a gap junction links two closely successive postsynaptic elements, as described above.

4. Regulation of electrical synapses

It is long established that gap junctional coupling in peripheral tissues is highly regulated [304,305], and it is therefore no surprise that gap junction channels between neurons are equally subject to regulation of their deployment, turnover, and permeability state. Indeed, there recently has been considerable emphasis placed on the plastic nature of electrical synapses [232,301,306]. Ideas surrounding this plasticity have resurrected interest in earlier work showing that neuronal gap junctional coupling in mammalian systems can be altered by a host of neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory substances, including dopamine [307–310], noradrenaline [200], serotonin [311], histamine [312], acetylcholine [313], and nitric oxide [311,314]. It is now accepted that the coupling strength of electrical synapses, involving changes in gap junctional conductance, is regulated by modulatory neurotransmitters, and mounting evidence indicates it is also influenced by the activity of the network in which they participate via activation of glutamatergic synapses. Interactions between glutamatergic transmission and electrical synapses, as well as activity-dependent regulation of these synapses in developing and adult CNS, have gained more recent attention (reviewed in [301,306]). While the presence of neuromodulators seems to be required to maintain the changes in coupling strength, plastic changes involve long-term modifications in coupling strength triggered by brief activation of chemical synapses, which outlast the induction period. This distinction is somehow arbitrary, as neuromodulators were reported to trigger long-term changes in electrical transmission that outlast the exposure period [315,316]. Neuronal burst firing was also shown to trigger long-term changes in coupling strength, adding a second form of activity-dependent plasticity [231,317].

The influence of monoamines on electrical coupling has particularly far-reaching implications. Neuromodulatory transmitters were shown to modify electrical coupling in the retina, leading to profound reorganization of neural circuits [187], suggesting that electrical synapses in other areas of the CNS could be similarly regulated to modify function. Widespread axonal projections to many areas of the CNS arise from dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus, serotonergic neurons in brainstem nuclei, and histaminergic neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus. Each of these systems has a broad influence on a variety of physiological processes, motor and sensory functions, and cognition. Further, the first three of these systems are acted upon by many drugs used clinically to treat neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, depression) and by drugs of addiction (e.g., cocaine, amphetamine). It is quite possible that by modifying activities of these transmitters, therapeutic and addictive drugs may exert their beneficial or adverse actions, in part, by altering signal transmission at electrical synapses [318–322]. In the case of the locus coeruleus, which has been intensively studied in relation to roles in learning, memory, and reinforcement behavior [323,324], its diverse projections greatly expand brain regions where monoamines and drugs acting on monoamine systems could modulate neuronal electrical coupling. Further, neurons in the locus coeruleus are themselves coupled by gap junctions [95] and are heavily innervated by dopaminergic fibers [325], providing for potential dopamine and dopaminergic drug actions at electrical synapses between these neurons. Just as understanding of processes involved in chemical synaptic transmission has served as a basis for deciphering sites and mechanisms of drug action at chemical synapses, so too, knowledge of modulators and cellular processes that regulate electrical synapses will be essential for understanding how malfunction of these synapses may contribute to CNS disease and is expected to provide insight into mechanisms for potential actions of drugs on cellular processes that regulate electrical synapses.

5. Regulation of Cx36 by phosphorylation

Cx36 contains three c-terminus serine amino acid residues (ser293, ser306 and ser315) and an additional cytoplasmic loop residue (ser110), all of which are phosphorylated by protein kinase (PKA) in vitro, with ser293 being the primary phosphorylation site [326,327]. Several early studies of the effects of Cx36 phosphorylation state on conductance at electrical synapses in mammalian CNS [326,328,329] suggested that uncoupling of ON cone bipolar cells and AII amacrine cells [326] resulted from phosphorylation of Cx36 following activation of D1 receptors and consequent activation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) and PKA acting on Cx36 [326]. This view has been challenged by Kothmann et al [330], who provided evidence that uncoupling occurs via an alternative pathway to that proposed by Urschel et al [326]. In this model, D1 receptors activate PKA, which in turn activates protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A) localized to Cx36-containing gap junctions, resulting in uncoupling by Cx36 dephosphorylation. Indeed, small ensembles of gap-junctionally-coupled neurons were shown to undergo modulated moment-to-moment changes in their strength of coupling based on state of phosphorylation, as determined by differential labeling using antibodies against phosphorylated vs. non-phosphorylated Cx36 [330].

6. Rectification of electrical transmission in the mammalian CNS