Abstract

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is an important deterministic factor in predicting colorectal carcinoma (CRC) progression. It is also evident that microsatellite instability (MSI) which results in a hypermutable phenotype of genomic DNA is common in CRC. Owing to the scarcity of reports from India, our aim of this study was to understand the clinicopathological correlations of CEA status with surgery and chemotherapy, correlate the same with socio-demographic status of the patients, determine the MSI status amongst them and understand the prognostic implications of CEA and MSI as CRC progression marker amongst patients. The serum CEA level was estimated by chemiluminescence assay (CLIA). Serum liver enzyme assay was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions using auto-analysers (E. Merck and Sera mol. Health Care, India). MSI analysis was carried out by PCR-SSCP. From our study, most frequently detected colorectal cancer was in 40–49 years age group (25.26%) with 61.05% male and 38.95% females. CEA showed a significant association with higher TNM staging, tumour size, smoking habit and MSI status (p < 0.05) but not with sex and site of cancer (p > 0.05). After surgery and chemotherapy, CEA and WBCs were decreased significantly (p < 0.05), while liver enzymes did not change significantly (p > 0.05). Overall, microsatellite instability was observed in approximately 40% of the populations. From our study, it was also evident that for both, MSI and abnormal CEA level predicted poor prognosis for the patient (by using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis; p = 0.04). Thus, CEA and initial MSI status can be used as prognostic markers of CRC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13193-017-0651-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CRC, CEA, Chemotherapy, MSI, Socio-demographic status

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer in men and the third most common for women worldwide [1]. During the past few decades, the incidence of CRC has increased two to four times in many Asian countries, with the concurrent etiological factors being genetic predisposition, physical activity, chemical exposure, high caloric intake and decreased intake of low-fibre diet [2]. A strong association exists between socio-demographic factors and self-evaluation of health status, lifestyle and environmental factors [3]. Thus, clinical assessment as well as cytology or histopathological examinations play a vital role in the management of CRC [4]. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a set of glycoproteins, normally found in foetal gastrointestinal tissue, is abundantly expressed in CRC and is widely used as a serum tumour marker of CRC [5]. Based on the TNM staging (i.e. Primary tumour, nodal status and metastases), CRC patients are grouped into four stages—stage I (within the subserosa, node-negative tumours), stage II (beyond the subserosa, node-negative tumours), stage III (non-metastatic node-positive tumour) and stage IV (any metastasis).

Advanced tumour stages and risk of recurrence can be indicated by high pre-operative and pre-chemotherapeutic CEA level (>5 ng/ml). One aim of the present study was designed to assess the effect of surgical removal and chemotherapeutic treatment on the level of CEA and other liver enzymes, as in most of the cases of CRC, metastasis to liver has been reported leading to liver abnormality and elevated liver enzymes. To this effect, initial purpose of this study was to correlate CRC with several clinicopathological parameters viz. age groups, sex, site of cancer, dietary habits, CEA status, TNM staging and tumour size. This is also to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of CEA as a diagnostic as well as a prognostic tool.

Defective DNA mismatch repair, a commonly found molecular alteration, results in microsatellite instability i.e. repeat length polymorphism of a microsatellite marker, resulting in DNA hypermutability. From previous study, prevalence of MSI was reported to be 12–15% of CRC patients [6]. MSI and locally advanced stage of CRC influence the role of CEA as a prognostic marker [7].

To understand the contributing effect of MSI on CRC, blood DNA of a random set of 70 patients with or without high CEA and before surgery was screened for MSI status using conventional markers (Table S-I). Our study was aimed to analyse the role of CEA as well as high MSI status to be a prognostic marker for CRC amongst Eastern Indian patients.

Materials and Methods

This is an analytical, cross-sectional study. Ninety-five patients (aged between 18 years to above 70 years) were included in this study after confirmed endoscopic examinations leading to a diagnosis of CRC. Out of the 95 CRC patients, 70 were also taken for MSI analysis. A detailed clinical history was taken during the last 3 years i.e. from April 2012 to April 2015. Seventy subjects attending hospital for routine check-up and no abnormalities were included as control group.

During this study, the signs and symptoms of these patients have been critically observed along with their complete blood count and other blood parameters. These were performed at an interval of 2 weeks through routine check-up. The entire study was approved by the ethical committee of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Cancer Research Institute, Kolkata, following the guidelines given by Indian council of Medical Research. Consents were obtained from the patients before including them in the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients who were suffering from CRC, currently diagnosed by endoscopic examination and biopsy and who have not previously received any anticancer therapy were included in this study. Healthy subjects with or without any type of infections, other than CRC, or any other cancer were also taken for MSI analysis (n = 70) but were excluded from other analysis.

Chemotherapeutic Regimen

Combination of 5-fluorouracil (450 mg/m2) and calleucovorin (20 mg/m2) chemotherapeutic regimen was used daily for 5 days given by intravenous infusion, and the cycle was repeated every 28 days for 6 cycles.

Blood Sample Collection for Biochemical Study

Blood samples were taken from the patients 1 week before and after the surgery. For patients receiving chemotherapy after surgery, blood samples were collected after 1 week of the first cycle of chemotherapy.

Preliminary Haematological Study

Haematological parameters like red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC) and haemoglobin (Hb) were analysed in Sysmex-KX 21 (Selangor, Malaysia).

Serum Liver Enzyme Assay

Alanine transaminase (ALT), total serum bilirubin (TSB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bilirubin levels were estimated, following the manufacturer’s instructions using auto-analysers (E. Merck and Sera mol. Health Care, India).

CEA Level

The serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was estimated by chemiluminescence assay (CLIA) using automated PC-RIA Mas Stratec (Germany), Beckman Coulter AccessR 2 (USA), Beckman Coulter Uniccel™ DXI 600 (USA), AdviaCentaurR (Siemens, USA), AdviaCentaurR XP (Siemens, USA). The reference range was 5 ng/ml.

Histopathology

Histopathological tests were done in the laboratory with standard laboratory protocol by using 10% formalin as fixative and double stained with haematoxylin and eosin to study the cell morphology and tumour grade.

CT Scan

CT scan of whole abdomen (plain and contrast study) was done.

Blood DNA Isolation and MSI Analysis

Blood DNA isolation followed by MSI analysis of patients (n = 70) and healthy subjects (n = 70) was carried out by PCR-SSCP following Giannattasio et al. [8] and Faghani et al. [9] with little modifications. Briefly, 100 ng/μl DNA templates were used in a PCR mixture containing 10 pmol of each primer, 1.5–2 mM MgCl2 and 1 U Taq polymerase. PCR amplification was performed by the following methods: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s (for BAT 25), 45 °C for 30 s (for BAT 26) and 55 °C for 30 s (other markers), and extension at 72 °C for 30 s with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were checked for MSI status by running in 15% non-denaturing acrylamide (60: 1, acrylamide/bisacrylamide) gels followed by EtBr stain. Due to more sensitivity and specificity of mononucleotide markers than dinucleotide markers in identifying MMR-deficit cancers, the specific panel of mononucleotide markers was selected for our study [10, 11]. Table S-I indicates the markers used for MSI.

Statistical Analysis

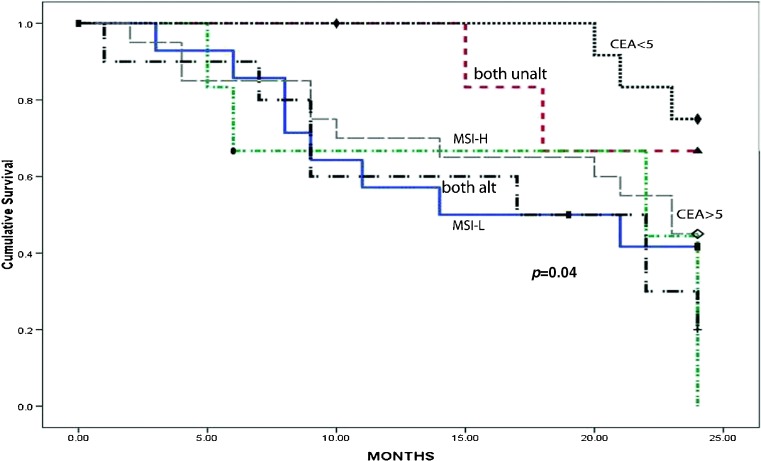

The result of different biochemical assays was expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). Finally, statistical analysis was done by one-way ANOVA, Spearman correlation and receiver operating curve (ROC) using SPSS (Version 20). Mean value of CEA was determined by average ± 2 SD (standard deviation). For all comparisons, p < 0.05 was considered as level of significance. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of surgery to the date of most recent follow-up or death (up to 3 years) by using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival of CRC patients (up to 3 years) with/without alterations of MSI and/or CEA

Results

Patient Demography

Out of the 95 CRC patients included in this study, 58 were males (61.05%) and 37 were females (38.95%). The age distribution of patients ranged from 18 years to above 70 years with peak age between 40 and 49 years (25.26%). The detailed age distribution of colorectal cancer patient is shown in Fig. S1.

Among 95 cases, majority were from urban population (68.42%; n = 65) followed by rural population (31.58%; n = 30) cases (Table S-II). Among the study population, 86 patients (90.53%) thrived on normal food containing fish, meat and vegetable (Table S-II).

Association of CEA Status with Tumour Stage, Grade, Size of Tumour, Smoking Habit and Liver Enzymatic Status

Significant association of high CEA status was found with stage II in comparison to stage I (p = 0.0475) and also in stage IV than stage II (p = 0.004), increasing tumour size (p = 0.001) and smoking habit (p = 0.013) (Table 1), but not with sex and site of cancer (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison between the patients (N = 95) with preoperative low CEA, high CEA in different T, N, M staging, tumour size, primary location, sex, habits, MSI status with p values

| CEA < 5 (N = 27) | CEA > 5 (N = 68) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distant metastasis (M) | M0 | 15 | 13 | 0.0004 |

| M1 | 12 | 55 | ||

| Nodal status (N) | N0 | 12 | 14 | 0.0221 (N2 vs N3) 0.0006 (N0 vs N3) 0.001 (N1 vs N3) |

| N1 | 11 | 19 | ||

| N2 | 4 | 12 | ||

| N3 | 0 | 23 | ||

| Primary tumour size (T) | T1 | 7 | 1 | 0.018 (T1 vs T2) 0.004 (T3 vs T4) 0.0003 (T2 vs T4) |

| T2 | 9 | 14 | ||

| T3 | 11 | 20 | ||

| T4 | 0 | 33 | ||

| Stages | I | 4 | 0 | (I vs II) 0.0475 (II vs IV) 0.004 |

| II | 19 | 21 | ||

| III | 4 | 32 | ||

| IV | 0 | 15 | ||

| Tumour size | <5 | 11 | 10 | 0.001 |

| ≥5 | 16 | 58 | ||

| Site | Colon | 16 | 41 | 0.312 |

| Rectum | 11 | 27 | ||

| Sex | M | 16 | 42 | 0.889 |

| F | 11 | 26 | ||

| Habit | Smoker | 12 | 43 | 0.013 |

| Non-smoker | 15 | 25 | ||

| MSI status (n = 70) | MSI-H + L | 3 | 25 | 0.003 |

| MSI-S | 30 | 12 |

Prognostic factors of CRC not only act as a guide to overall prognosis but also determine the need for adjuvant therapy. These factors are interrelated. In the present study, tumour size (T), nodal status (N), grade of the tumour and serum CEA level were taken as prognostic factors (Tables 2, 3, and 4). After surgery and subsequent first cycle of chemotherapy, patients showed significant decrease of CEA and WBCs (p < 0.05), while liver enzymes did not change significantly (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 2.

Relationship between size of tumour and lymph node involvement in colon cancer patients (N = 95)

| Nodal status | Primary tumour size | Total no. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | ||

| No. (%) | |||||

| N0 | 8 (30.77) | 13 (50) | 5 (19.23) | – | 26 (100) |

| N1 | – | 10 (33.33) | 20 (66.67) | – | 30 (100) |

| N2 | – | – | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 16 (100) |

| N3 | – | – | – | 23 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Total no. (%) | 8 (8.42) | 23 (24.21) | 31 (32.63) | 33 (34.74) | 95 (100) |

Table 3.

Relationship between histopathological grading and primary tumour size in colon cancer patients (N = 95)

| Primary tumour size | Histopathological grade | Total no. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| T1 | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | – | – | 8 (100) |

| T2 | – | 20 (86.96) | 3 (13.04) | – | 23 (100) |

| T3 | – | 16 (51.61) | 15 (48.39) | – | 31 (100) |

| T4 | – | – | 18 (54.55) | 15 (45.45) | 33 (100) |

| Total no. (%) | 4 (4.21) | 40 (42.11) | 36 (37.89) | 15 (15.79) | 95 (100) |

Table 4.

Profile of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), WBCs, and liver function tests in colorectal cancer patients (N = 95) before and after resection and chemotherapy

| Parameters | CEA (ng/ml) | WBC (103/μl) | ALP (U/l) | ALT (U/l) | TSB (mg/dl) | Albumin (g/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | |

| Before surgery | 39.48 ± 8.58 | 10.40 ± 0.68 | 272.93 ± 9.40 | 44.15 ± 3.13 | 1.63 ± 0.10 | 3.62 ± 0.15 |

| After surgery | 26.46 ± 5.87 | 7.13 ± 0.25 | 258.73 ± 8.06 | 40.16 ± 1.50 | 1.54 ± 0.08 | 3.82 ± 0.11 |

| After chemotherapy (after 1 week of first cycle) | 14.74 ± 3.03 | 4.97 ± 0.18 | 276.41 ± 10.65 | 42.80 ± 1.78 | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 3.67 ± 0.12 |

| p value | .022 (S) | .000 (S) | .376 (NS) | .446 (NS) | .447 (NS) | .507 (NS) |

p value—among groups

ALP alkaline phosphatase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, TSB total serum bilirubin, S significant, NS non-significant

CEA as a Marker for CRC

The staging of CRC is crucial for optimal management of the disease. The mean value of CEA was 1.09 ± 1.95 (ranged from 0.86 to 3.04 ng/ml) for lower grade of CRC, while for grade II, grade III and grade IV patients, the mean serum CEA ranged from 5.69 ± 10.08 to 91 ± 124.12, respectively.

In addition, 95 patients with CRC were further investigated with a receiver operating curve (ROC) (Fig. S2) to evaluate whether the preoperative serum CEA level can be used as a marker of CRC recurrence. The area under ROC curve of CEA preoperative level was 0.979 (95%CI 0.957 to 1.000, p = 0.000); the sensitivity was 81% when the cut-off value was 5 ng/ml.

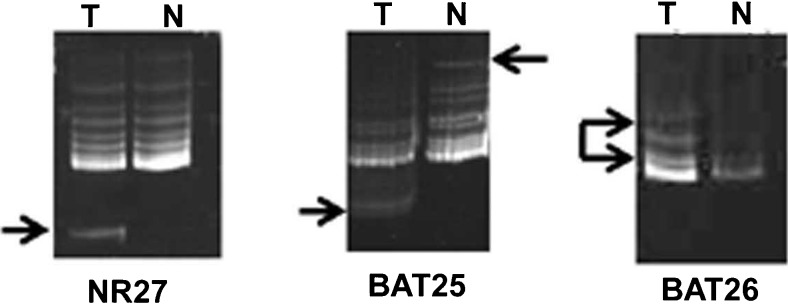

MSI Status

Out of the 70 patients screened for MSI, 40% presented with high MSI status (Table 1, Fig. 2) indicating repeat length polymorphism of STRs analysed here, arising from defects in mismatch repair pathways of DNA damage resulted in development of CRC in those patients. In our present study, a strong correlation was found between CEA and MSI status (p = 0.003) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Arrowheads indicating positive results of MSI as detected by PCR-SSCP in non-denaturing 10% PAGE. T blood DNA from CRC patients, N blood DNA from normal individual

Survival Analysis

The Kaplan-Meier (K–M) survival analysis revealed poor prognosis of CRC patients with MSI positivity alone or along with high serum CEA (>5) than in patients with both unaltered or those with low CEA (<5) or (p value = 0.04).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first report from Eastern India highlighting the implication of both MSI and CEA status in predicting patient outcome. In the present study, 95 cases of colorectal cancer patients were taken as the studied population. The majority of the previous studies from Western countries [12] showed a mean age of 60 years. Whereas in our study, the frequencies of colorectal cancer was 25.26% in the age group of 40–49 years followed by 22.1% cases in 50–59 years age group (Fig. S1). The mean age ± SEM of the study population was 46.35 ± 1.8. In our study, males (61.05%) were predominant than female (38.95%) (Table 1). Similar reports were observed in Western Countries [13]. This study revealed that CRC is mostly prevalent among urban population (68.42%) (Table S-II) which portrays the exact similar scenario of other study [14]. This may be the cause of dietary factor, distance barriers, economic factor and other resource constraints which reduce rural population to access primary health care.

In the past few years, CRC have experienced unprecedented boom in India. Although there have been great improvements in early detection and treatment of CRC, it remains an important public health problem. Modern research on the carcinogenesis mechanisms stimulate the investigation for molecular biomarkers which would help to provide better prognosis for disease advancement [15]. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) remains the most studied contemporary tumour marker of colon cancer [16]. The prognostic value of CEA level is not yet clear, but many authors believe that CEA can be used as a supportive criterion to assess the colon cancer prognosis. From previous studies, we have come to know that high pre-operative CEA level indicates poor prognosis [17]. Another study by Ahmad et al. [18] revealed that CEA has implication in diagnosis of CRC. Thus, this study will help to gather more information to evaluate the usefulness of serum CEA level as a diagnostic as well as a prognostic tool. The reason behind lower prevalence of CEA in woman population might be attributed to their oestrogen status as it is evident that oestrogen may have a protective effect against the progression of CRC [19]. Sajid et al. [20] confirmed that the rate of smoking plays an important role in elevating the CEA levels which was also observed in the present study (Table 1). Like previous reports [21], our study also showed significant association between TNM staging and tumour size with the serum CEA level (p < 0.05) (Table 1). This may be the cause of tumour vascularization with an increased possibility of occult systemic metastases. From our study, we have found that grade I CRC patients had threshold value of serum CEA of 0.86–3.04 ng/ml, while CEA level of 4.39–15.77, 16.86–69.84 and 33.12–215.12 ng/ml indicates grades II, III and IV, respectively. The correlations of serum CEA level threshold value with increasing CRC grade and stage can be a useful prognostic marker for CRC in Eastern India.

Microsatellite instability (MSI), another hallmark of CRC, has been found to be high in our study as well as in previous reports [22, 23]. Out of 70 samples screened for MSI, 6 were MSI-H (8.6%), 22 were MSI-L (31.4%) and 42 were MSI-S (60%). This indicated the emergence of MSI type CRCs in India. Halder et al. [24] reported a gradual increase of right-sided colon cancer in Eastern India, the factor that might contribute to the increased prevalence of MSI-type colon cancer. A previous study showed a positive correlation between MSI and CEA as a prognostic marker [25], which is also reflected in our present study (p = 0.003) (Table 1). Thus, both MSI and CEA level can be used as a useful predicting marker of CRC. Concurrent with our findings, a strong association of CEA and MSI has also been previously reported in Søreide et al., indicating their prognostic implication in CRC detection [7]. In the present study, MSI status, however, did not show any correlation with age, sex, tumour size, stage, grade and node involvement (data not shown).

This study also evaluated the level of CEA expression with MSI status in relation to recurrence and survival during 3 years follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed positive MSI status and high preoperative CEA level in CRC patient to be associated with poor prognosis, indicating that both MSI and preoperative high CEA level are a necessary event for development of CRC (Fig. 1).

After surgery and chemotherapy, there was a significant fall of WBC count, compared to the same in untreated CRC patients (Table 4). In colon cancer, profuse neutrophil infiltration can contribute to initial high level of WBC count, which can get decreased after surgical removal of the tumour and even at a lower value upon chemotherapeutic interventions. In a previous study, Wang et al. [26] reported that increased neutrophil count can foster CRC progression through recruitment of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1/IL-6. In the present study, although the WBC count had fallen after surgical removal of tumour, it remained within the normal range (Table 4). Lee et al. [27] also figured out a strong association of increased WBC with CRC progression and increased mortality.

Liver function tests were done to detect liver metastasis. Unlike previous reports [28], our data did not find any liver metastasis (Table 4).

Thus, to conclude, our data showed that CEA as well as MSI can be used in monitoring disease progression. Initial CEA level and MSI status is needed for predicting CRC progression in day-to-day clinical practice.

Conclusions

Our data showed that high CEA (>5) has significant correlation with TNM staging, tumour size, smoking habit and MSI status (p = 0.00–0.013) and it is an important diagnostic as well as a prognostic marker in advanced stages of CRC. This study will also help to identify different stages of CRC with their cut-off value of CEA. Our data also showed that 40% of the CRC patients were MSI-positive categories and no distinct clinico-pathological correlation was observed between high MSI status with patient age, sex, tumour size, grade, stage and node involvement. However, a distinct correlation was observed with positive MSI status and elevated level of serum CEA (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis also indicated poor prognosis amongst patients with both MSI and high CEA (Fig. 1), indicating their prognostic implication as CRC markers. Thus, to conclude, both CEA and MSI should be included as useful prognostic markers in predicting CRC, especially in the Eastern Indian population.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Age profile of colorectal cancer patients (N = 95) (GIF 5 kb)

Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) for pre-operative levels of CEA to predict the colorectal cancer recurrence (N = 95). (GIF 10 kb)

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all the patients and other staffs of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Cancer Research Institute for their continuous support. All grants were received from institutional research and development section.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13193-017-0651-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23(38):6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. LancetOncol. 2005;6(11):871–876. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauliūnė S, Kalėdienė R, Kaselienė S, Jaruševičienė L. Health profile of the urban community members in Lithuania: do socio-demographic factors matter? Medicina. 2014;50(6):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpelan-Holmstom M, Haglund C, Lundin J, Jarvinen H, Roberts P. Pre-operative serum levels of CA 242 and CEA predict outcome incolorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(7):1156–1161. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ojima T, Iwahashi M, Nakamura M, et al. Successful cancer vaccine therapy for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-expressing colon cancer using genetically modified dendritic cells that express CEA and T helper-type 1 cytokines in CEA transgenic mice. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(3):585–593. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2073–2087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Søreide K, Søreide JA, Kørner H. Prognostic role of carcinoembryonic antigen is influenced by microsatellite instability genotype and stage in LocallyAdvanced colorectal cancers. World J Surg. 2011;35(4):888–894. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannattasio S, Lattanzio P, Bobba A, Marra E. Detection of microsatellites by ethidium bromide staining. The analysis of an STR system in the human phenylalanine hydroxylase gene. Mol Cell Probes. 1997;11(1):81–83. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1996.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faghani M, FakhriehAsl S, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Aminian K, Tarang A, Seighalani R, Javadi A. The correlation between microsatellite instability and the features of sporadic colorectal cancer in the north part of Iran. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:756263. doi: 10.1155/2012/756263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suraweera N, Duval A, Reperant M, Vaury C, Furlan D, Leroy K, Seruca R, Iacopetta B, Hamelin R (2003) Evaluation of tumor microsatellite instability using five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats and pentaplexPCR. Gastroenterology 123(6):1804–1811. doi:10.1053/gast.2002.37070 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Søreide K. High-fidelity of five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats to high-frequency microsatellite instability distribution in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the colon. Anticancer. Res. 2011;31(3):967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmignani CP, Hampton R, Sugarbaker CE, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Utility of CEA and CA 19-9 tumor markers in diagnosis and prognostic assessment of mucinous epithelial cancers of the appendix. J SurgOncol. 2004;87(4):162–166. doi: 10.1002/jso.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cushiari A, Steele RJC, Moossa AR (2002) Essential surgical practice. 4thed. New York. Arnold 581-5.

- 14.Cole AM, Jackson JE, Doescher M. Urban–rural disparities in colorectal cancer screening: crosssectional analysis of 1998–2005 data from the centers for disease Control’s behavioral risk factor surveillance study. Cancer Med. 2012;1(3):350–356. doi: 10.1002/cam4.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanopienė D, Smailytė G, Vidugirienė J, Bacher J. Impact of microsatellite instability on survival of endometrial cancer patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2014;50(4):216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold P, Freedman SO. Demonstration of tumor-specific antigens in human colonic carcinomata by immunological tolerance and absorption techniques. J Exp Med. 1965;121:439–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.121.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma CJ, Hsieh JS, Wang WM, Su YC, Huang CJ, Huang TJ, Wang JY. Multivariate analysis of prognostic determinants for colorectal cancer patients with high preoperative serum CEA levels: prognostic value of postoperative serum CEA levels. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22(12):604–609. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70360-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad B, Gul B, Ali S, Bashir S, Mahmood N, Ahmad J, Nawaz S. Comparative study of carcinoembryonic antigen tumor marker in stomach and Colon cancer patients in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(11):4497–4502. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.11.4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sajid KM, Parveen R, Durr-e-Sabih, Chaouachi K, Naeem A, Mahmood R, Shamim R. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in hookah smokers, cigarette smokers and non-smokers. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57(12):595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Ahwal MS, Abdo Al-Ghamdi A. Pattern of colorectal cancer at two hospitals in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(3):164–169. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.33320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shemirani AI, et al. Simplified MSI marker panel for diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(8):2101–2104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jass JR. HNPCC and sporadic MSI-H colorectal cancer: a review of the morphological similarities and differences. Familial Cancer. 2004;3(2):93–100. doi: 10.1023/B:FAME.0000039849.86008.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halder SK, Bhattacharjee PK, Bhar P, Pachaury A, Roy Biswas R, Majhi T, Pandey P (2013) Epidemiological, clinico-pathological profile and management of colorectal carcinoma in a tertiary referral Center of Eastern India. JKIMSU 2(1)

- 25.Søreide K, Søreide JA, Kørner H. Prognostic role of carcinoembryonic antigen is influenced by microsatellite instability genotype and stage in locally advanced colorectal cancers. World J Surg. 2011;35(4):888–894. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Wang K, Han GC, Wang RX, Xiao H, Hou CM, Guo RF, Dou Y, Shen BF, Li Y, Chen GJ. Neutrophil infiltration favors colitis associated tumorigenesis by activating the interleukin-1 (IL-1)/IL-6 axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7(5):1106–1115. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YJ, Lee HR, Nam CM, Hwang UK, Jee SH. White blood cell count and the risk of colon cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47(5):646–656. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.5.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffy MJ. Carcinembryonic antigen as a marker for colorectal cancer: is it clinically useful? ClinChem. 2001;47(4):624–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Age profile of colorectal cancer patients (N = 95) (GIF 5 kb)

Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) for pre-operative levels of CEA to predict the colorectal cancer recurrence (N = 95). (GIF 10 kb)

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)