Abstract

It is not clear how often epithelial tumours affect young women. This study aimed to evaluate the clinico-pathological pattern and survival outcome of women, 40 years and younger, with cancer ovary. Women 40 years and younger, operated between 2008 and 2012 for ovarian cancer, were retrospectively recruited and followed up. The study design was descriptive as well as a survival analysis. A hybrid of retrospective and prospective cohort design was used for risk factor analysis. Of the 115 women less than 40 years being operated for probable ovarian cancer, 22 were excluded for various reasons. Demographic details, clinical presentations, histopathological features, treatments and survival outcomes were studied. The primary outcomes looked for were death and recurrence. Secondary outcomes were complications of treatment and fertility. The predominant histology in the study population was epithelial tumour (70%), and serous adenocarcinoma was the commonest tumour type. The overall survival rate was 87%, and progression free survival was 63%. Time to death and recurrence were dependent on stage of disease, histology of tumour, primary treatment and residual disease at surgery. In multivariate analysis, the hazard ratio for recurrence in advanced stages was 12.6 (95% CI 3.5 to 45.5; p < 0.001) as compared to early stage disease. Epithelial ovarian cancers are common in young women. Death and recurrence are more likely in women with epithelial cancers, advanced stage disease and in those with residual tumour at cytoreductive surgery.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Young women

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the third most common cancer among Indian women, next to cancer of the breast and the cervix [1]. It has the highest fatality to case ratio of all female cancers due to its insidious and vague clinical presentation, lack of effective screening methods and advanced presentation in two-third of cases [2]. It is accepted that epithelial ovarian tumours constitute 90% of all ovarian cancers with germ cell tumours, sex cord stromal tumours, other rarer tumours and metastatic tumours making up the rest.

Ovarian cancer is generally considered as a disease of postmenopausal women with only 10 to 15% found in premenopausal women [3]. The peak incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer, which is the commonest histological type, is at 60 to 65 years of age with less than 1% of epithelial ovarian cancers found in women less than 30 years of age [4]. Ovarian germ cell tumours occur primarily in women between 10 and 30 years of age and constitute 70% of ovarian tumours in this age group [5]. Although most studies in the literature combine clinical features, treatment and outcomes of epithelial and non-epithelial ovarian cancers in young women, these need to be studied separately. The aim of this observational study was to present the clinico-pathological patterns of ovarian cancer in women 40 years or younger in a tertiary care centre in India and to compare the survival outcomes based on stage, histology, residual tumour and the effect of chemotherapy given prior to or after surgery.

Methods

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Settings

This study was conducted in a tertiary level hospital in Tamil Nadu state, India which has a dedicated oncology unit. Patients who underwent surgical treatment (primary surgery or interval debulking) for ovarian cancer from 1st January 2008 to 31st December 2012 were included in this study.

Study Design

The study was done as a retrospective audit of operated cases in a single institution. It was a hybrid of a retrospective and prospective design in that the follow-up was done in a prospective fashion. Survival analysis was done for the primary outcomes, and a cohort design was used for assessing risk factors.

Data Collection

Patients were identified through the electronic medical records. All the patients fulfilling our inclusion criteria were contacted by phone or letter and asked to come for review. Oral consent was obtained to include the patient for study, and written consent was taken if they attended clinic as requested. If patient had expired, the details of death were obtained from a relative. The patient’s demographic details, clinical presentations, histological features, treatments and survival outcome data were collected mainly by reviewing the electronic medical records. When necessary, inpatient and outpatient paper charts were also studied.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients ≤40 years with histologically proven ovarian cancer

Underwent surgery (primary cytoreduction or interval debulking) in our hospital between January 2008 and December 2012

Primary ovarian cancers

Exclusion Criteria

Patients above 40 years of age

Those who did not have ovarian cancer in final histology

Patients who were treated with chemotherapy only and not operated

Those who were operated in other centres

Those who had ovarian tumours secondary to cancer from other organs

Outcomes

The primary outcomes analysed were survival and recurrence. Death and time to death, recurrence and time to recurrence were studied in women 40 years or younger who had surgery for ovarian cancer at our institution from January 2008 to December 2012.

The secondary outcomes analysed were complications of treatment, fertility after treatment and risk factors for death and recurrence.

Sample Size

With 90% expected survival probability, 95% confidence interval, 7.5% precision and alpha error of 5%, the calculated sample size was 72. This was calculated as the follow-up was done prospectively to get statistical significance.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for all variables. Continuous variables which were normally distributed were expressed using mean and standard deviation, and non-normal continuous variables were expressed using median and range. For categorical variables, percentages were used, and for comparing two categorical variables, crosstabs with chi-square statistics were obtained. Kaplan-Meir estimation method was used to get the estimates of mean survival and recurrence time. Tarone-Ware test was applied to check the significance of difference in survival between two groups. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 20.

Results

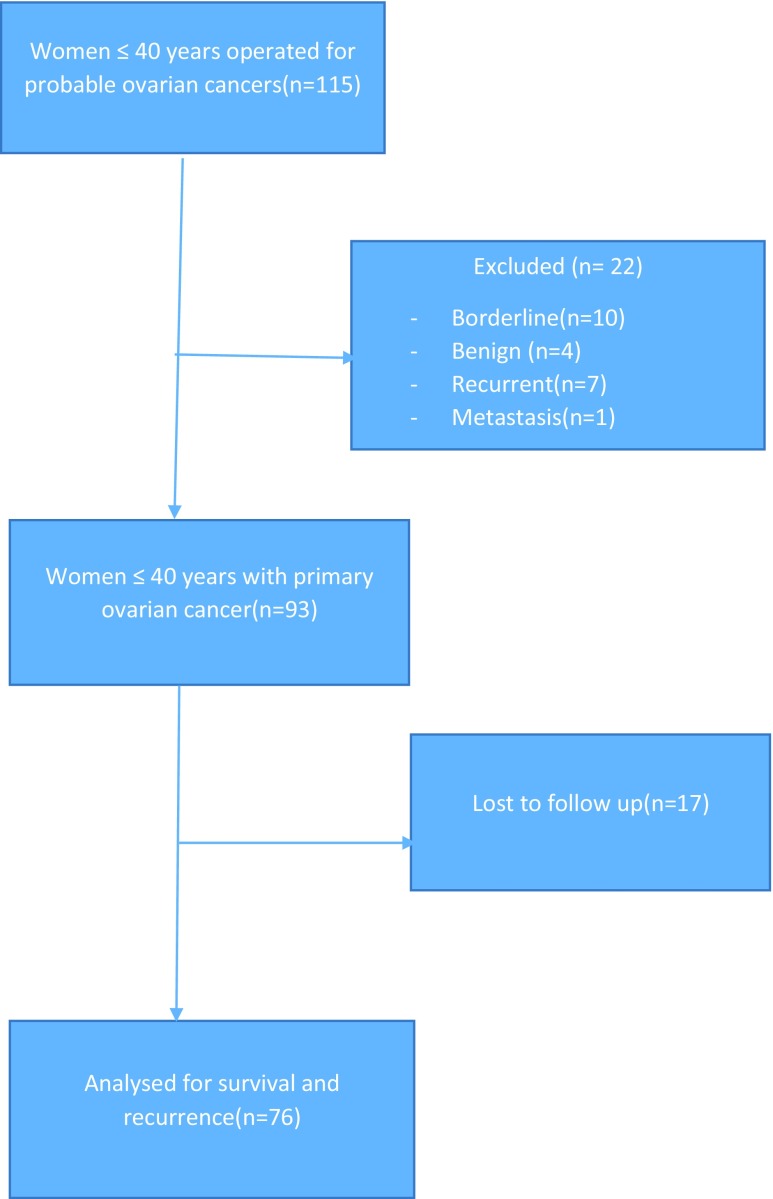

There were 1084 women who underwent surgery for probable ovarian cancer during the study period in all age groups of which 115 women (8.5%) were less than 40 years of age. Among the 115 women, 22 women were excluded as the final histopathology report was borderline ovarian tumour in 10, non-cancers in 4, recurrent tumours in 7 and metastatic tumour in 1. Thus, 93 women fulfilled our eligibility criteria and the baseline characteristics, clinico-pathological patterns, treatment given and immediate complications were analysed in them. However, follow-up for survival and recurrence could be done in only 76 patients as others did not have correct contact information (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing patient recruitment

The baseline characteristics, histopathological pattern and treatment details of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. Of the 93 patients with primary ovarian cancers, 72 (77.4%) had primary debulking surgery and 21 (22.6%) had neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking. Surgical staging was done according to the FIGO 1988 system. The complexity of the surgery was graded as simple, intermediate or complex, depending upon the procedures done during the surgery. Surgeries of simple complexity involved salpingo-ophorectomy and hysterectomy. Surgeries involving pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissections and complete omentectomy also were classified as intermediate complexity surgeries and those involving bowel resections, bladder involvement or repairs, diaphragm stripping, liver nodule resection or splenectomy were classified under severe complexity surgeries.

Table 1.

Histopathological pattern and treatment details of the study patients

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Feature | n | Range | Number | Percentage |

| Age < 20 | 93 | 13 to 40 | 10 | 10.8 |

| Nulliparous | 93 | 0 to 6 | 31 | 33.3 |

| BMI > 30 | 85 | 17.1 to 43 | 28 | 32.9 |

| ECOG >2 | 87 | 0 to 3 | 6 | 6.9 |

| Albumin <3.5 | 63 | 2 to 5 | 12 | 19.1 |

| CA 125 > 200 | 82 | 2 to 19,100 | 28 | 34.2 |

| hCG > 5 | 35 | 0.1 to 6142 | 14 | 40.0 |

| AFP > 5.5 | 36 | 0.5 to 4,96,274 | 18 | 50.0 |

| LDH > 460 | 35 | 67.3 to 17,400 | 24 | 68.6 |

| Histopathological characteristics (n = 93) | ||||

| Feature | Number | Percentage | ||

| TYPE | ||||

| Epithelial | 67 | 72.0% | ||

| Germ cell | 21 | 22.5% | ||

| Sex cord stromal | 3 | 3.2% | ||

| Others | 2 | 2.2% | ||

| GRADE | ||||

| 1 | 15 | 16.1% | ||

| 2 | 13 | 14.0% | ||

| 3 | 21 | 22.6% | ||

| Not done | 44 | 47.3% | ||

| STAGE | ||||

| Early stage (Ia–IIc) | 47 | 50.5% | ||

| Advanced (IIIa–IVb) | 46 | 49.5% | ||

| Treatment details (n = 92) | ||||

| TREATMENT MODE | ||||

| Primary surgery | 72 | 77.0% | ||

| Primary chemotherapy | 21 | 23.0% | ||

| SURGICAL COMPLEXITY | ||||

| Simple | 21 | 22.6% | ||

| Intermediate | 69 | 74.2% | ||

| Complex | 3 | 3.2% | ||

| RESIDUAL DISEASE | ||||

| None | 56 | 60.2% | ||

| ≤1 cm | 15 | 16.1% | ||

| >1 cm | 22 | 23.7% | ||

| FERTILITY SPARING | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 24.7% | ||

| No | 70 | 75.3% | ||

Of the 67 patients with epithelial ovarian cancers, 31 (46.3%) had serous histology, 23 (34.3%) had mucinous tumour, 11(16.4%) had endometrioid and 2 (3.0%) had clear cell tumours. There were 21 patients with malignant germ cell tumours, of which 9 (42.9%) were mixed germ cell tumours, 5 (23.8%) were immature teratoma, 4 (19.0%) were yolk sac tumours and 3 (14.3%) were dygerminomas. There were 3 granulosa cell tumours in the sex cord stromal group. There was one patient with granulocytic sarcoma of the ovary and one with malignant haemangio-endothelioma. About 47.3% of histopathology reports did not describe grade of the tumour. Many serous tumours and clear cell tumours did not have grading. Sex cord and germ cell tumours are usually not graded. About 46 patients (49.5%) had advanced carcinoma of the ovary, of which follow-up could be done in 38 patients (82% of advanced cases). Among the advanced group, 37 patients (80.1%) belonged to the epithelial group, of which 31 patients were followed up and 9 patients (19.5%) belonged to non-epitheloid group of which 7 patients were followed up.

Out of 93 patients, 71 (76.3%) patients had optimal debulking, of which 51 patients (n = 67, 76.1%) belonged to epithelial ovarian group and 20 patients (n = 26, 76.92%) belonged to non-epitheloid group.

Fertility sparing surgery was done in 23 patients; all of whom belonged to the non-epithelial ovarian cancer group—21 patients with germ cell tumours, 2 with granulosa cell tumours and 1 with haemangio-endothelioma. On follow-up, we found that 3 (13.0%) of our patients who had germ cell tumours had become pregnant after completion of treatment and had given birth to live term babies. Two patients conceived without any treatment, and one patient conceived after ovulation induction.

There were no patients who died intraoperatively or within 28 days of surgery among the 93 patients who were operated. The commonest complication was postoperative fever which was found in 19.4% of those who had surgery. There were 5 cases of wound infection, a case of paralytic ileus and a case of parastomal abscess. One patient who had ureteric injury intraoperatively underwent ureteroneocystostomy, and her postoperative period was uneventful. A patient with mucinous adenocarcinoma who underwent interval debulking procedure had relaparotomy for haemoperitoneum on postoperative day 2. Another patient who developed burst abdomen on postoperative day 10 underwent repair with vicryl mesh. There was no case of thromboembolism in any of our operated patients.

Only 76 (52 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and 24 patients with non-epithelial ovarian cancer) out of the 93 patients could be followed up for analysing primary outcome measures like survival and recurrence. There were 10 deaths recorded during our follow-up period with an estimated mean survival time of 5.4 years (95% CI 4.9 to 5.9). Of the 76 patients who were followed up, 28 (36.8%) developed recurrence with a mean recurrence time of 4.3 years with a standard error of 0.29 years (95% CI 3.7 to 4.8).

Survival and recurrence based on variables like histology, stage of the disease, primary treatment given and residual tumour at the end of surgery were analysed separately.

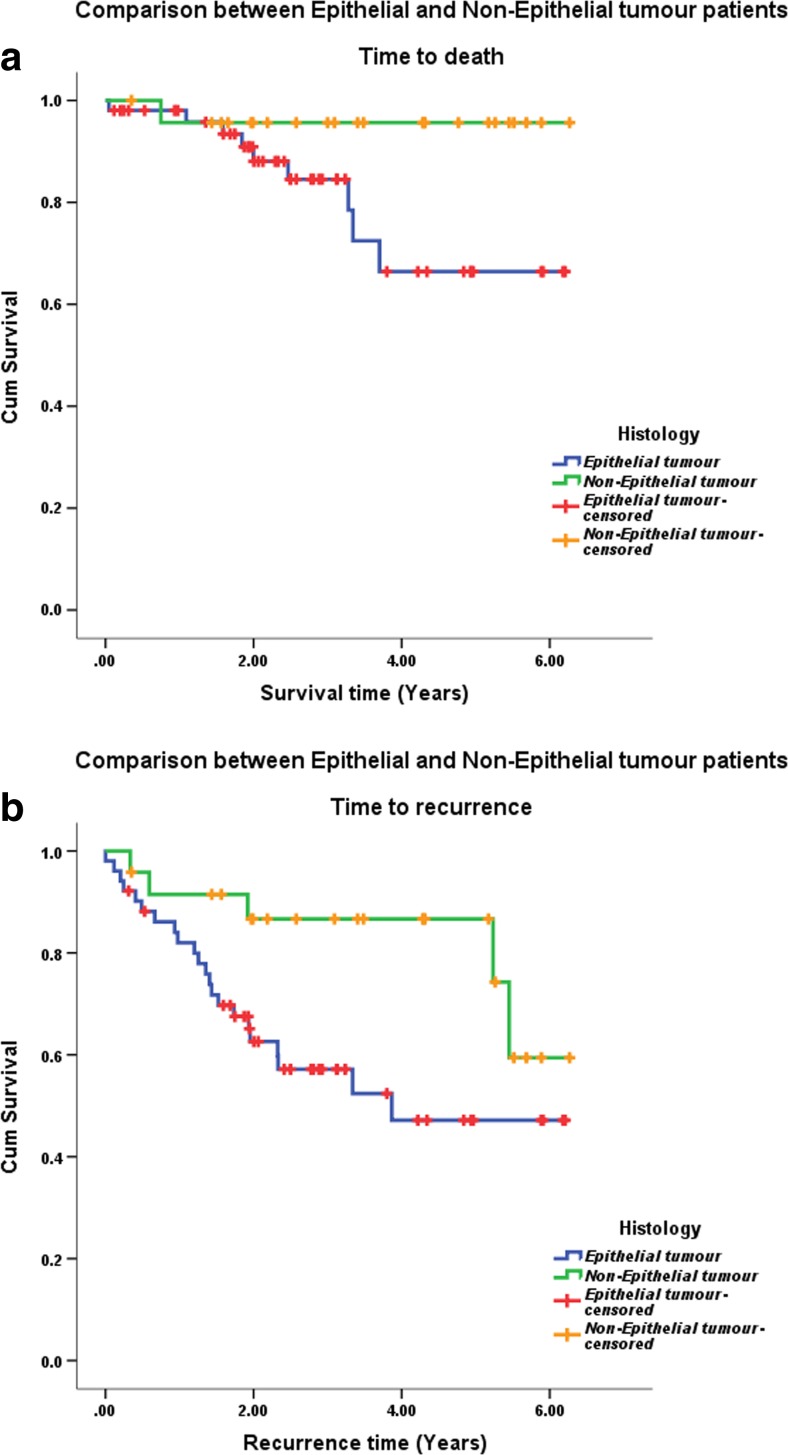

As for comparison of survival time for epithelial and non-epithelial tumours, there were a total of 52 patients in the epithelial group with a mean survival time of 5 years (95% CI 4.3 to 5.7) and 24 patients in the non-epithelial group with a mean survival time of 6 years (95% CI 5.6 to 6.5). The epithelial group had 9 deaths and non-epithelial group had 1 death. The patient who died in the non-epithelial group had haemoangio-endothelioma of the ovary. There were no deaths found among those who could be followed up after germ cell tumours and sex cord stromal tumours. There was no statistically significant difference in the overall survival by histology.

There were 23 patients (44.23%) who developed recurrence in the epithelial group and 5 patients who had recurrence in the non-epithelial group (20.83%). Of the 5 patients in the non-epithelial group, 4 patients (19.04%) had germ cell tumour and 1 had ovarian sarcoma. There was no recurrence detected in the sex cord stromal group during our follow-up period. The time to recurrence for epithelial tumours was 3.8 years (95% CI 3.1 to 4.5) and for non-epithelial tumours was 5.3 years (95% CI 3.7 to 4.9), as shown in Fig. 2. This was statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (a) and disease-free survival (b) by tumour histology

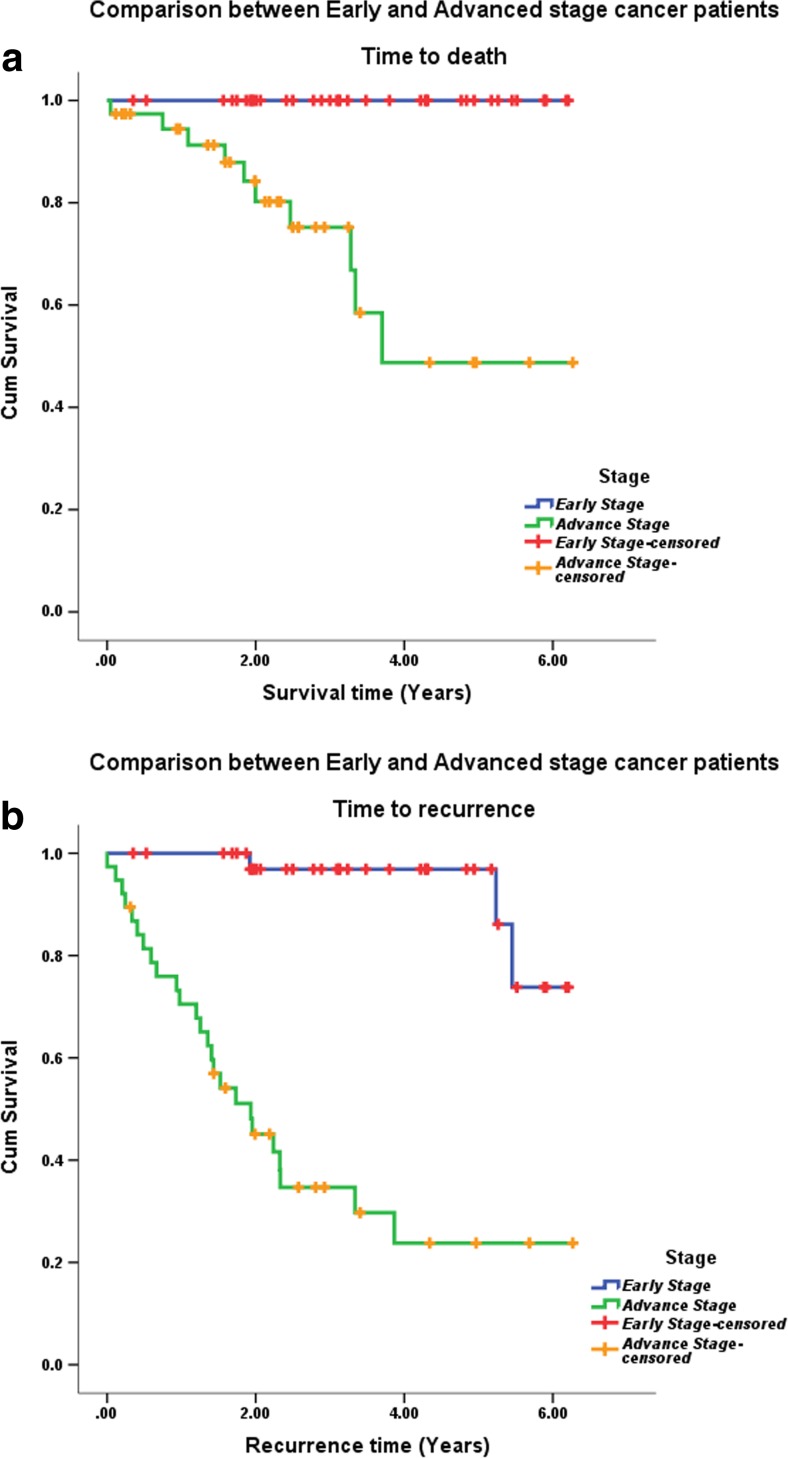

The time to death by stage of cancer could not be calculated as all the 38 patients in early stage had survived till the follow-up period. In the advanced stage group (stages III and IV), 10 out of the 38 patients had died with an overall survival of 73.7%. A clear difference in survival curves was seen between early and late stage disease, as shown in Fig. 3. There was a statistically significant difference in time to recurrence (5.9 versus 2.7 years) between patients with early stage and advanced stage disease (p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Overall survival (a) and disease-free survival (b) by stage of disease

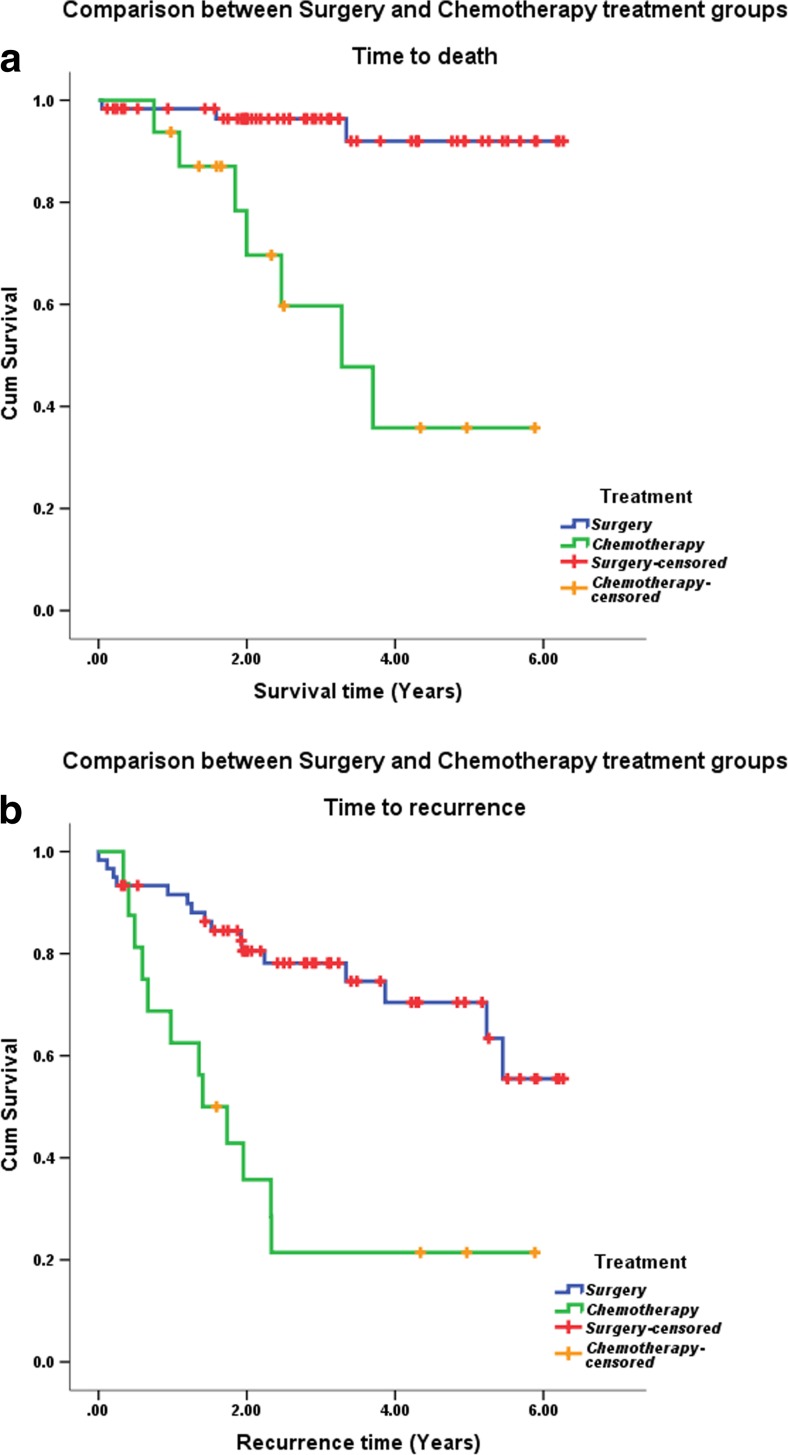

The mean overall survival time for primary surgery was 6 years (95% CI 5.6 to 6.3) and for primary chemotherapy was 3.6 years (95% CI 2.2 to 4.7), as shown in Fig. 4. This was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The mean time to recurrence after primary surgery was 4.8 years (95%CI 4.2 to 5.4) and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 2.3 years (95% CI 1.2 to 3.3). This too was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Overall survival (a) and disease-free survival (b) by primary treatment

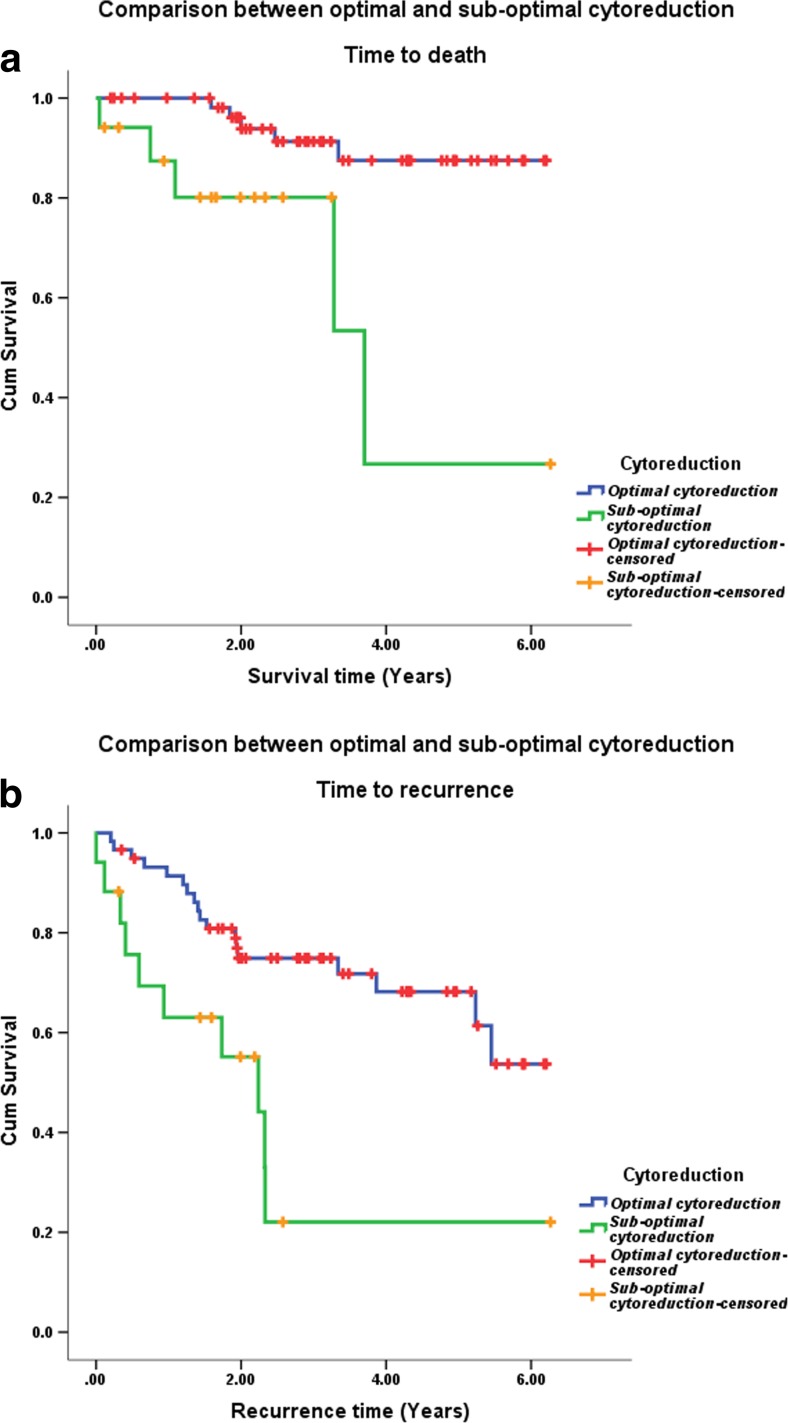

The overall survival and progression free survival based on optimal versus suboptimal debulking are shown in Fig. 5. The overall survival rate was 91.5% for optimal cytoreduction with mean survival time of 5.7 years (95% CI 5.3 to 6.1). The survival rate was 70.6% for suboptimal cytoreduction with a mean survival time of 3.7 years (95% CI 2.3 to 5.1). This was statistically significant (p value 0.003). Progression-free survival was 70 and 41%, while mean survival time was 4.7 and 2.4 years (p value 0.002) for optimal and suboptimal groups, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Overall survival (a) and disease-free survival (b) based on optimal vs suboptimal debulking

The univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of potential risk factors affecting survival of ovarian cancer patients after surgery in women less than 40 years of age showed that only primary treatment modality was significant for overall survival, as depicted in Table 2. Those who had primary chemotherapy were 10 times more likely to die as compared to those who had primary surgery.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of potential risk factors affecting survival and recurrence of ovarian cancer patients after surgery

| Factors affecting survival | Number | Survival status | Unadjusted (univariate) | Adjusted (multivariate) | |||

| Dead (n) | Alive (n) | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| 1. Histology | |||||||

| Non-epithelial | 0.10 | 0.49 | |||||

| Tumour | 24 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Epithelial tumour | 52 | 9 | 43 | 5.81 (0.73–46.22) | 2.22 (0.23–21.34) | ||

| 2. Treatment | <0.001 | 0.25 | |||||

| Surgery | 60 | 3 | 57 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 16 | 7 | 9 | 10.17 (2.62–39.4) | 2.42 (0.54–10.64) | ||

| Variables affecting recurrence | N | Recurrence status | Unadjusted (univariate) | Adjusted (multivariate) | |||

| Yes (n) | No (n) | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| 1. Histology | |||||||

| Non-epithelial | 24 | 5 | 19 | 1 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Epithelial | 52 | 23 | 29 | 2.7 (1.02–7.30) | 2.36 (0.74–7.51) | ||

| 2. Treatment | |||||||

| Surgery | 60 | 16 | 44 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.42 |

| Chemotherapy | 16 | 12 | 4 | 4.3 (2.01–9.31) | 1.44 (0.60–3.48) | ||

| 3. Stages | |||||||

| Early stage | 38 | 3 | 35 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Advanced stage | 38 | 25 | 13 | 14.1 (4.21–47.4) | 12.6(3.49–45.49) | ||

Cox proportional hazard model for recurrence is shown in Table 2. Epithelial histology, primary chemotherapy and advanced stage at presentation were significant adverse factors for recurrence on univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, the only independent risk factor for recurrence was stage of the disease. The hazard ratio for recurrence in advanced stages was found to be 12.6 (95% CI 3.5 to 45.5, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Most of the studies from India on ovarian cancer in women 40 years and younger are case reports and clinico-pathological studies. Survival studies done for ovarian cancer below 40 years of age, especially for epithelial ovarian cancers in India, are scarce. The aim of our study was to look at the clinico-pathological patterns of ovarian cancer in women 40 years and younger treated at a tertiary care hospital in India and to find out the overall survival and progression-free survival for the same based on histology, stage, chemotherapy given prior to or after surgery and residual disease after surgery.

We were able to follow-up 76 patients out of the 93 patients with ovarian cancer at or below 40 years of age (81.7%). In spite of trying to contact the patients and their relatives by letters, phone calls and e-mail, 18.3% of patients were lost to follow-up. This is a common problem in our country where patients default due to ignorance, poverty and lack of a permanent address. Access to cancer care is limited, and often patients have to travel long distances. Most patients do not have insurance. Cancer hospitals are also ill equipped to contact patients who default and arrange financial help for the poor.

The commonest clinical presentation was abdominal pain in 46% of these young women with ovarian cancer in our study. In another Indian series on young women with malignant ovarian tumours, the most common presentation was pain abdomen [6]. About 50% of our women were in Stage 1 or II. In our study, the survival of early stage ovarian cancer was almost 100%, advanced stage ovarian cancer was 74% with an overall survival rate of 87%. A study on clinico-pathological and survival pattern in 72 patients with malignant germ cell tumour done by Neeyalavira et al. found that two-thirds of the patients presented at an early stage and advanced stage was found to be a risk factor for recurrence similar to our study [7]. In a study from eastern India on 957 women with ovarian neoplasms over a period of 10 years, the overall survival rate was 85% for Stage I, 65% for Stage II, 30% for Stage III and 15.5% for Stage IV tumour [8]. Women of all age groups were included in the above study.

In our study, epithelial cancers were seen in 72% of all ovarian cancers less than 40 years of age. The commonest histological type was serous cystadenocarcinoma which constituted 33.3% of all ovarian cancers in young women. Germ cell tumours constituted 23% of cases. Early stage disease and non-epithelial histology had the best prognosis in multivariate analysis. Though there was statistically significant difference in time to recurrence between epithelial and non-epithelial tumours (3.8 versus 5.3 years), we could not show a significant difference in time to death between the 2 groups as the numbers were small. A Chinese study by Tang et al. on young women with epithelial ovarian cancer showed the commonest histologic type to be serous adenocarcinoma (56%) [9]. For Stage IA disease, their 2- and 5-year survival was 86 and 82%. They concluded that women under 35 years with epithelial ovarian cancer mostly have early stage serous adenocarcinoma with good prognosis and so such women could have fertility sparing surgery.

Cox proportional hazard model showed that those who had primary debulking surgery had better overall survival compared to neoadjuvant chemotherapy which was statistically significant. Although this was statistically significant, it may be because primary surgery was done mainly for those with early stage disease and neoadjuvant chemotherapy was done for those with advanced disease and morbidly ill at presentation. The survival rate and progression-free survival rate also improved with optimal cytoreduction when compared to suboptimal surgery which was also statistically significant. Most studies have shown that optimal cytoreduction is the most important prognostic variable, at least the one variable that something can be done about. A study done by Talukdar et al. showed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by fertility sparing surgery could be a reasonable option for malignant germ cell tumours not suitable for optimal cytoreductive surgery [10]. A study on granulosa cell tumour done over a 10-year period showed that optimal cytoreduction was a good prognostic factor [11]. The presence of nuclear atypia and increased mitosis was the other factors that impacted survival significantly. Age, stage of the tumour, parity and size of the tumour had no significant effect on survival in this study.

Limitations

The present study analysed available data of all the patients who underwent surgery for ovarian tumour in our hospital during a 5-year period from 2008 to 2012. The major limitation of our study is that 18.3% of patients were completely lost to follow-up after surgery. Information on the others were also gained mainly by phone calls and letters. It was a big challenge to contact our patients as telephone numbers were often not provided. Also, telephone and postal numbers provided to the hospital were incorrect or had not been updated. There could be a bias in the follow-up in that there could have been more complications, recurrences and deaths in the 17 women who were completely lost to follow-up. Since this was mainly a retrospective analysis, collection of information could have been incomplete with a differential bias. Another limitation was the small number of events. Only 10 deaths had been identified in the 76 patients that were followed up. This made risk factor analysis difficult. The treatment outcomes of epithelial ovarian tumours are compared with non-epithelial tumours which is a heterogenous group consisting of germ cell tumours, sex cord stromal tumours and other miscellaneous types. Though it would have been ideal to compare outcomes of all the groups separately as they are biologically different, the number of patients with sex cord stromal tumours and other miscellaneous types were too small for meaningful statistical analysis. Statistical assumptions could have been violated in the multivariate analysis.

Strengths

This study is one of the first in India to look at ovarian cancers in young women. In our hospital, the medical records, laboratory data and radiological reports are stored electronically. Hence, access and retrieval of patient information are relatively easy. In the past few years, more and more patients and their family members have mobile phones and can be easily contacted.

Another strength of this study was the good statistical analysis as the institution has a well-established department of biostatistics. Survival analysis could be done stratified for the important variables such as histology, stage of the disease, primary treatment type and optimal cytoreduction.

Suggestions for Improved Care

In order to improve our comprehensive cancer treatment services, capacity building of all the professionals responsible for patient care as well as documenting and storing medical records of the patients is essential. There has been a push for a Cancer Registry for the country. Standardizing our diagnostic methods and our treatments so that these can be audited for quality improvement is to be encouraged. All the professionals concerned should follow a minimum standard of reporting and documentation. Electronic entry of all information about the patient, contact address, e-mail and phone numbers would make follow-up and ascertainment of disease status easier. The employment of social workers to contact defaulters and referral to professionals nearer the patient’s home would ensure that compliance to treatment is enhanced.

Conclusion

Even in women 40 years and less, 72% of the ovarian cancers were epithelial in origin with serous adenocarcinoma being the most common histology. Germ cell tumours constituted 23% of the ovarian cancers of which mixed malignant germ cell tumour was the commonest type. The mean overall survival was 5.4 years, and the overall survival was 87%. For epithelial tumours, the overall survival was 82% and for non-epithelial tumours it was 96%. For early stage disease, it was 100%, but for advanced stages, it was 73%. Disease recurrence was seen in 37%. The mean overall progression free survival time was 4.3 years. For epithelial tumours, the mean progression-free survival time was 3.8 years, and for non-epithelial tumours, it was 5.3 years. For early stage disease, it was 5.9 years, and for advanced stages, it was 2.7 years. Early stage disease and non-epithelial histology had the best prognosis.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Takiar R, Nadayil D, Nandakumar A. Projections of number of cancer cases in India by cancer groups. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1045–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin LM, Trivers KF, Matthews B, Andrilla CHA, Miller JW, et al. Vignette based study of ovarian cancer screening: do US physicians report adhering to evidence based recommendations? Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:182–194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berek JS, Bast RC Jr. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR et al.,editors. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th ed.Hamilton(ON): BC Decker;2003

- 4.Chen LM, Berek JS. Ovarian and fallopian tubes. In: Haskell CM, editor. Cancer treatment. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2000. p. 55

- 5.Zalel Y, Piura B, Elchalal U, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant germ cell ovarian tumours in young females. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;55:1. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(96)02719-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deodhar KK, Suryawanshi P, Shah M, Reki B, Chinoy RF. Immature teratoma of the ovary: a clinico-pathological study of 28 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:730–735. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.85097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neeyalavira V, Suprasert P. Outcomes of malignant ovarian germ cell tumours treated in Chiang Mai University Hospital over a nine year period. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:4909–4913. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.12.4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondal SK, Banyopadhyay R, Nag DR, Roychowdhury S, Mondal PK, Sinha SK. Histologic pattern, bilaterality and clinical evaluation of 957 ovarian neoplasms: a 10 year study in a tertiary hospital of eastern India. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7:433–437. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.92011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang L, Zheng M, Xiong Y, Ding H, Liu FY. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer in young reproductive women. Ai Zheng Chin J Cancer. 2008;27:951–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talukdar S, Kumar S, Bhatla N, Mathur S, Thulkar S, Kumar L. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced malignant germ cell tumours of ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranganath R, Sridevi V, Shirley SS, Shantha V. Clinical and pathologic prognostic factors in adult granulosa cell tumours of ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:929–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]