Abstract

Context

Ventricular assist devices (VADs) improve quality of life in advanced heart failure (HF) patients, but there are little data exploring psychological symptoms in this population.

Objective

This study examined the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and disease over time in VAD patients.

Methods

This prospective multicenter cohort study enrolled patients immediately before or after VAD implant and followed them up to forty-eight weeks. Depression and anxiety were assessed with PROMIS SF8a questionnaires. The panic disorder, acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM were used.

Results

Eighty-seven patients were enrolled. Post-implant, depression and anxiety scores decreased significantly over time (p=0.03 and p<0.001 respectively). Two patients met criteria for panic disorder early after implantation but symptoms resolved over time. None met criteria for ASD or PTSD.

Conclusions

Our study suggests VADs do not cause serious psychological harms and may have a positive impact on depression and anxiety. Furthermore, VADs did not induce PTSD, panic disorder or ASD in this cohort.

Keywords: Ventricular assist device, depression, anxiety

Introduction

Ventricular assist devices (VADs) are increasingly used to treat patients with advanced heart failure (HF).1 VADs were originally approved as a temporary therapy to “bridge” patients as they waited for a donor organ for cardiac transplantation but are now also implanted in patients who are ineligible for transplantation (destination therapy). Nearly 12500 patients have received a device since 2006 in the United States alone.2 As the number of patients with VADs has increased, there has been expanded discussion on integrating palliative care into patients with advanced HF.3, 4 This, in addition to Medicare’s requirements for palliative care to be involved in the care of patients who are undergoing VAD implantation as destination therapy5, reinforces the relevance of fully understanding the natural history of symptoms after implant in order to tailor palliative care intervention.

While these devices improve survival and quality of life in patients with advanced HF6, there are little data exploring the natural history of psychological symptoms over time in these patients. This is an important topic to examine as heart failure itself can have an effect on psychiatric health, in particular depression.7 The literature on psychological symptoms in patients with VADs is restricted to depression, anxiety8–12, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the majority of these studies included only a small number of patients (e.g. a range of 14–30 patients). Psychological symptoms may have an impact on adherence to treatment in heart failure, as demonstrated in recent studies.13

We studied VAD patients to examine prevalence of depression, anxiety, panic disorder, acute stress disorder and PTSD, and change in psychological symptoms over time.

Methods

Design Overview

This was a multi-center prospective cohort study conducted from November 2010 through December 2012. Patients were enrolled during the hospitalization when the device was implanted at four high volume VAD implanting medical centers across the United States immediately before or after implant and followed for up to forty-eight weeks after VAD placement. If patients received a transplant, they were censored at transplantation. Patients were eligible for this study if they were age 21 and older, fluent in English, had a caregiver or family member who was willing to be enrolled in a related cohort study, and had reliable access to a telephone. We limited eligibility to English-speakers because most of the study instruments have only been validated in English. Institutional review boards of participating centers and the coordinating center approved the protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent. We anticipated there may be a lack of response at any one interval as this is a sick population and they may often not feel well enough to answer the surveys. By providing six opportunities after the peri-implant period, we maximized our ability to capture symptoms after implant. We felt it was important to take into consideration exactly what time this data was collected, thus rigorously labeled the time period symptoms were assessed. We applied statistical models that took into consideration timing of the survey responses.

Instruments

Outcomes were elicited through structured patient questionnaires. These were administered peri-implant by cardiology nurse practitioners (NPs) at the bedside. After implant, surveys were conducted by a research assistant via telephone. Patients were called during the day, but if they did not answer, there was a least one attempt at night and one attempt during the weekend to reach them. The depression and anxiety modules of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form 8A were used and administered at the time periods indicated in Figures 2 and 3. PROMIS is a system developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that provides reliable measures of patient-reported outcomes for use in clinical studies in patients who have chronic diseases and in the general population.14, 15 It provides comparability, reliability and validity, flexibility, and inclusiveness15 across a range of patients and diagnoses. The PROMIS raw score for depression or anxiety are normed against a national sample and are converted to t-scores with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The panic disorder, acute stress disorder and PTSD modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID) were also used. Appendix A describes the times each survey was administered, if the instrument was not scheduled to be administered at a particular time point, “N/A” is in the corresponding box. Peri-implant questionnaires were administered either immediately before implant (Pre-Implant) or immediately after implant (“Immediately after implant”).

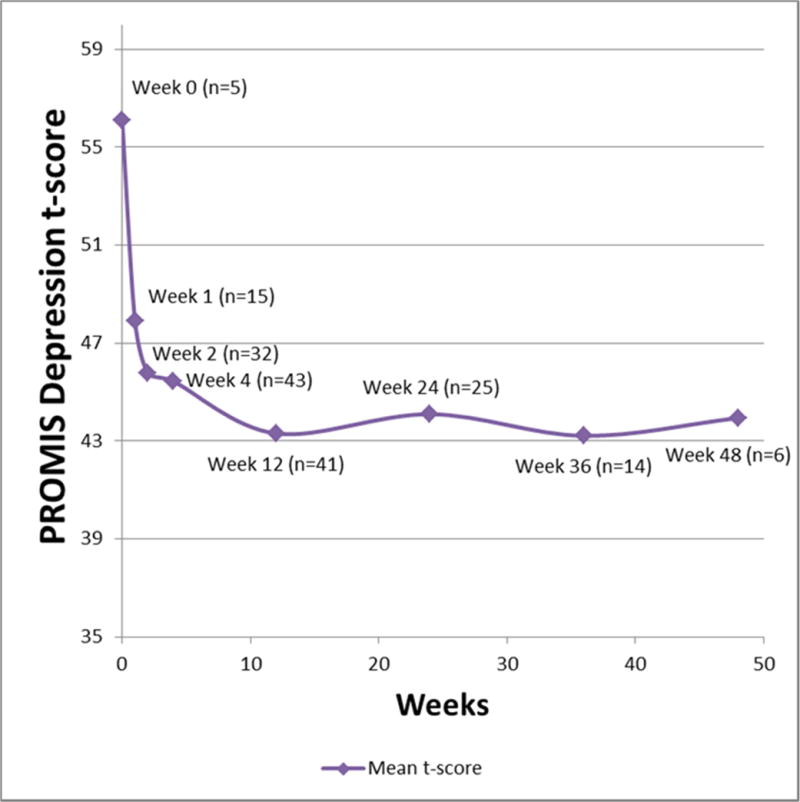

Figure 2.

PROMIS Depression SF8a scores over time in a cohort of VAD implanted patients. The score decreased over time (p=.03), indicating less depressive symptoms over time.

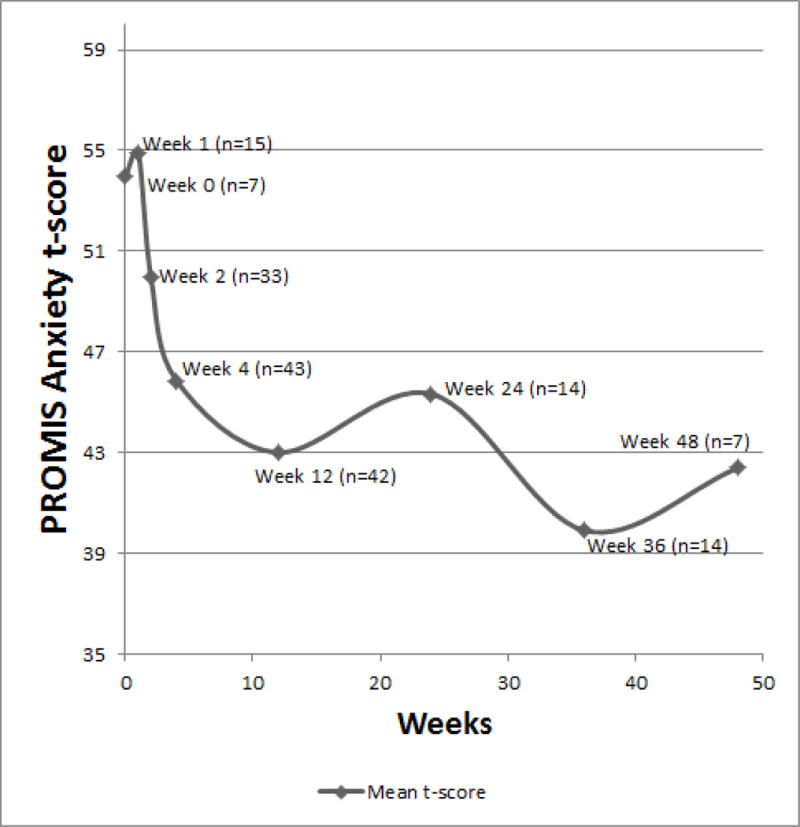

Figure 3.

PROMIS Anxiety SF8a scores over time in a cohort of VAD implanted patients. The score decreased over time (p<0.001), indicating less anxiety symptoms over time.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.3. We summarized dichotomous variables as proportions and continuous variables with a mean and standard deviation if they were normally distributed, if not, with a median and interquartile range.

We determined the overall prevalence and severity (as applicable) of the psychosocial symptoms over time. The linear mixed model regressions (PROC MIXED for normally distributed data and PROC GLIMMIX for non-normally distributed data) accounted for the structure of the data where assessments were nested within participants. These procedures implement two likelihood-based methods: maximum likelihood (ML) and restricted/residual maximum likelihood (REML).18 We found that missing data were missing at random – i.e. there was no specific pattern of missing data.19 A favorable theoretical property of ML and REML is that they accommodate data that are missing at random.20 Similar to multiple imputation, ML gives unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors. Linear mixed model regressions can also use subjects with missing data points as the time points with data still contribute to the ML.

Results

Patient Characteristics

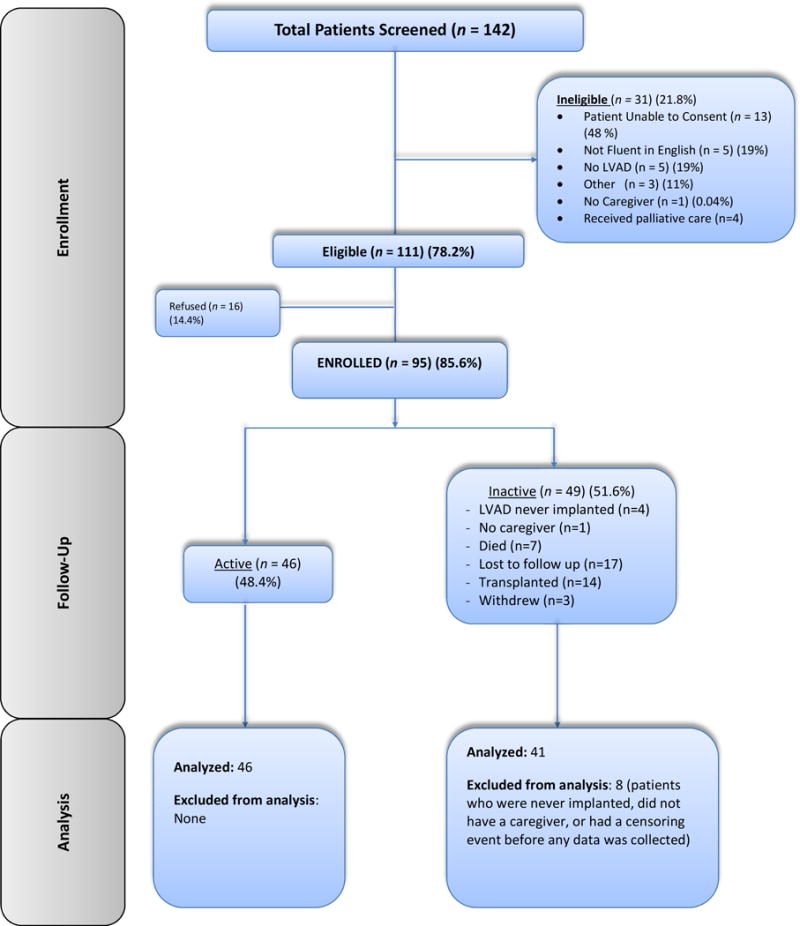

One hundred and forty-two patients were screened by nurses at each center and 111 (78%) were eligible for this study. From the eligible group, ninety-five patients (86% of eligible group) were enrolled, and ultimately eight-seven patients were analyzed (see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram). Forty patients were enrolled before implant. Thirty-four were enrolled immediately after implant. Five patients were enrolled two weeks after implant. Eight patients were enrolled four weeks or later after implant. A majority of the patients (57%) reported a history of myocardial infarction, 42% reported a history of diabetes, and few had cancer or other serious medical problems other than heart disease (See Table). The indication for VAD was bridge to transplant for 39% of this group, and 52% received the VAD as destination therapy. Indication was unknown for 9% of patients. Over the course of the study period, 7% of the patients died and 17% received a heart transplant.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of participant flow.

Instrument Outcomes

For each instrument, there was a 24%–88% (mean 49%, median 46%) response rate at each included time period. There was no bias between the instruments. If they were reached, the vast majority responded to all surveys that were administered at that time (see Appendix A).

Psychological Outcomes

The PROMIS Depression SF8a questionnaire mean t-score was 56 (±5) pre-implant, and 44 (±6) at forty-eight weeks, with decreasing scores over the study period (Figure 2). A generalized linear mixed (GLM) confirmed that the score decreased over time (p=.03). When BTT patients and DT patients were analyzed separately in a sensitivity analysis, there was no significant decrease over time (p=0.23 and p=0.16, respectively).

The PROMIS Anxiety SF8a questionnaire had a mean anxiety t-score of 53 (±12) pre-implantation, and 42 (±9) at forty-eight weeks post-implantation. A GLM model demonstrated that the score decreased over time (p<0.001) (Figure 3). When BTT patients and DT patients were analyzed separately in a sensitivity analysis, anxiety scores still significantly decreased over time (p<0.01 and p=0.03, respectively)

The SCID found two patients who met criteria for panic disorder. One of these patients met criteria at two weeks post implant but no longer met criteria at four weeks post implant. One patient met criteria at two and four weeks post implant but did not meet criteria for the screening question at twelve weeks post implant. None of the patients met criteria for acute stress disorder or PTSD.

Discussion

We evaluated depression, anxiety, panic disorder, acute stress disorder, PTSD and religiosity over time in a group of patients who underwent VAD implant. This study is the first to examine the prevalence of such a wide range of psychiatric diagnoses and religiosity in patients with VADs.

Psychological Outcomes

Undergoing a major procedure such as a VAD implant may produce anxiety or other psychological harms. Depression is the most common psychiatric diagnosis associated with HF. The overall prevalence of depression in HF patients in literature ranges from 15% to 55%21–25, with most studies demonstrating prevalence higher than in the general population (18%).26 As VAD patients received this device in order to ameliorate symptoms of HF, they may have an impact on depressive symptoms which are associated with HF.

We found depression and anxiety symptoms decreased over time for VAD patients (Figures 2 and 3). This may indicate patients were mildly depressed and anxious in anticipation of device implantation, and resolved after the procedure. There also may be a positive impact on psychological outcomes in these patients with end-stage HF because they feel reassured the VAD will extend their lives.6 There was a small increase in scores at the twelve month mark, however there were few patients remaining in the cohort at this time and 63% still in the study at 12 months were destination therapy patients. This increase may represent a “remainder effect” where the sickest patients remained as they were not eligible for transplant. In addition, depression scores did not significantly decrease over time when BTT and DT patients were analyzed separately, however, the results of these sensitivity analyses are questionable because analyzing the groups separately leaves few patients at certain time points and decreases the power of the analysis. Further studies should examine BTT and DT separately as these patients may be different as the indication for the VAD is different.

Previous studies examining depression in patients with VADs have been cross-sectional8–10, or have included infrequent follow up over about 6–15 months11, 12. Mapelli and Modica’s studies demonstrated that after VAD implantation, patients experienced mild anxiety or depression without significant changes over time. However, these studies examined small numbers of patients and were conducted in Italy where the patient population may be different from the United States, particularly with regard to disease severity and alternative treatment options, such as transplant. Our study also found some symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline, but symptoms decreased over time. VAD patients may have a lower prevalence of depression and anxiety at baseline compared to other HF patients because VAD patients are required to have a strong social network in order to be eligible for a VAD in many implanting centers. Given that a VAD can represent a significant life change for these patients, it is heartening to know that these devices do not appear to cause depression or anxiety.

Acute stress disorder and PTSD are also psychiatric disorders that are important to investigate in VAD patients, as the implantation of a relatively large device may be traumatic for some patients. None of the patients in our study met criteria for PTSD or acute stress disorder. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans is about 6.8%27 and there is limited research examining the prevalence of PTSD among patients with HF. A case control study among veterans demonstrated a 49% increase in the risk of PTSD in HF patients.28 Another cross-sectional study conducted in Europe examined the prevalence of PTSD in patients who were implanted with a VAD.29 Similar to our findings, none of the patients in that study met criteria for PTSD. Research on acute stress disorder after VAD placement is even more limited. One study demonstrated that 4% of 1344 patients admitted for myocardial infarction were diagnosed with acute stress disorder.30 While we did not observe any instance of acute stress disorder or PTSD, larger studies should be performed.

In contrast, 2.3% of our patients met criteria for panic disorder. The lifetime prevalence of panic disorder in the United States is 4.7%27, and a cross-sectional study of HF patients estimated the prevalence of panic disorder in HF patients to be about 9%.31 Our study demonstrated that VAD patients may experience a lower incidence of panic disorder compared to the general HF population. As noted above, we selected a group of patients that had caregivers, which may result in a lower prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Limitations

Our study is limited by high non-response rates at certain time points, particularly peri-implant. The window of time between the decision for VAD implant and the surgery can be very short, from a few hours to less than a day. This made completing surveys before VAD implantation difficult. In addition, the surveys done immediately after implant were performed by cardiology nurse-practitioners who also needed to teach the patient and his/her family about the VAD. Thus in many cases the completion of the survey instruments was a lower priority. We attempted to address the issue of missing data through using a mixed models approach. This approach allows us to use subjects with missing data points, as the time points with data still contribute to the overall maximum likelihood of the regression model, and provide insight on the progression of symptoms over time.

Lack of response later may have been because patients were too ill or were called at an inconvenient time to complete an in-depth survey. This may result in ascertainment bias. However, 16.7% of this cohort received a heart transplant, and were dis-enrolled after transplantation. Patients who are eligible for transplant tend to be healthier than patients that had the VAD placed as destination therapy. This may offset the ascertainment bias.

Given the differences in indications for patients who go for VAD placement, we performed a sensitivity analysis stratifying by indication that would control for the different demographic characteristics; however given the small numbers at certain time points this may not be a valid analysis and will need to be considered in future work examining this population.

We did not have the opportunity to rigorously define the baseline prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the majority of the study cohort prior to VAD implantation, due to the severity of illness and need to expedite VAD implantation.

Finally, we do not have information on complications after surgery such as infection, stroke, or bleeding, and these complications may also have a significant impact on psychological health.

Conclusions

VADs contribute meaningfully to patients’ quality of life. Our study suggests that VADs do not induce depression, anxiety, or PTSD. More studies need to be performed for illnesses such as panic disorder and acute stress disorder as our study was underpowered to assess these diseases.

The assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders is important to the overall care of VAD patients. Our data demonstrate that there are time periods during which patients with recently implanted VADs need increased attention to their psychological symptoms. Palliative care consultation in the care of patients with VADs provides an opportunity to address psychological and physical symptoms. The natural history this study demonstrates may have clinical implications. For example, one or two follow-ups with the palliative care team in the weeks post-implant may be sufficient to meet the needs of the vast majority of these patients. This can guide palliative care teams in allocating resources to the patients most in need, assuring better quality of care for patients with advanced cardiac disease and their families.

Table 1.

Baseline and Implant Characteristics* Among a Cohort of Patients Undergoing VAD Implant at Four Academic Medical Centers. The number of responses varies due to the timing of when patients completed the questionnaire; in many cases patients were enrolled either immediately before the VAD was implanted (and thus there was not time to complete the demographic form) or immediately after and they may not have been well enough to complete the questionnaires.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Indication for VAD placement (n=87) | |

|

| |

| Destination Therapy | 51.7 % (45) |

| Bridge to Transplant | 39.1% (34) |

| Unknown Indication | 9.2% (8) |

|

| |

| Device Type (n=87) | |

|

| |

| BiVAD | 1.1% (1) |

| LVAD | 95.4% (83) |

| Unknown | 3.4% (3) |

|

| |

| Manufacturer (n=87) | |

|

| |

| HeartMate II | 82.8%% (71) |

| Heartware | 13.8% (12) |

| Unknown | 4 (4.6%) |

|

| |

| Age (n=87) | 58.0 +/− 11.7 |

|

| |

| Gender (n=87) | |

| Women | 23% (20) |

| Men | 77% (67) |

|

| |

| Marital Status (n=45) | |

|

| |

| Married | 75.6% (34) |

| Separated | 11.1% (5) |

| Widowed | 2.2% (1) |

| Single/Never Married | 11.1% (5) |

| Divorced | 0 |

| Partnered/Living with Significant Other | 0 |

|

| |

| Medical Center (n=87) | |

|

| |

| Mount Sinai | 34.5% (30) |

| Columbia-Presbyterian | 19.5% (17) |

| University of Pennsylvania | 11.5% (10) |

| Jewish Hospital | 34.5% (30) |

|

| |

| Number of years of school (n=41) | |

|

| |

| <12 years | 9.8% (4) |

| 12–16 years | 75.6% (31) |

| >16 years | 14.6% (6) |

|

| |

| Highest Degree Obtained (n=41) | |

|

| |

| None | 4.9% (2) |

| Technical Degree/Diploma | 2.4% (1) |

| High School Diploma/GED | 48.8% (20) |

| Associates Degree | 14.6% (6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 12.2% (5) |

| Masters Degree | 12.2% (5) |

| Doctorate | 2.4% (1) |

| Other non-US Degree | 2.4% (1) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity (n=41) | |

|

| |

| Not of Hispanic/Latino/Spanish Origin | 90.2% (37) |

| Puerto Rican | 4.9% (2) |

| Other Hispanic/Latino/Spanish Origin | 4.9% (2) |

|

| |

| Race (n=41) | |

|

| |

| White | 58.6% (24) |

| Black/African American | 29.3% (12) |

| Asian | 2.4% (1) |

| Other | 7.3% (3) |

| White & Native American/Alaska Native | 2.4% (1) |

|

| |

| Income(n=41) | |

|

| |

| $10,000–$29,999 | 12.2% (5) |

| $30,000–$59,999 | 9.8% (4) |

| $60,000–$99,999 | 17.1% (7) |

| $100,000–$199,999 | 19.5% (8) |

| Don’t Know | 22.0% (9) |

| Refused | 17.1% (7) |

| Not Applicable | 2.4% (1) |

|

| |

| How much money do you have left over at the end of the month? (n=41) | |

|

| |

| Some money left over | 43.9% (18) |

| Just enough money to make ends meet | 34.2% (14) |

| Not enough money to make ends meet | 9.8% (3) |

| Don’t Know | 7.32% (3) |

| Refused | 2.4% (1) |

| Not Applicable | 2.4% (1) |

|

| |

| Comorbidities (n=50) | |

|

| |

| History of Heart Attack | 57.1% |

| History of Surgery for Peripheral Vascular Disease | 19.5% |

| History of Stroke/TIA | 12.2% |

| Asthma | 7.3% |

| COPD | 2.4% |

| Stomach problems/Peptic Ulcer Disease | 17.1% |

| Alzheimer’s disease/Other Dementia | 0.0% |

| Cirrhosis/Liver damage | 4.9% |

| Diabetes | 41.5% |

| Kidney problems/Dialysis/Transplant | 4.9% |

| RA/Lupus/PMR | 0.0% |

| Lymphoma | 0.0% |

| Leukemia/Polycythemia Vera | 0.0% |

| Other Cancer | 7.3% |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.0% |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD, categorical values are n (%)

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Mount Sinai Claude D Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG028741; New York, NY; Washington D.C.), grants from the Kornfeld Program in Bioethics (New York, NY), the Greenwall Foundation (New York, NY), and the NRSA T32 training grant (T32-HP10262; Washington D.C.). They had no role in the in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data. They played no role in writing the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication

Disclosures

Dr. Pinney has received consulting fees and honoraria from Thoratec, Inc. Dr. Slaughter has received research and grant support from HeartWare.

Appendix A: Instrument response rates

Denominator is the number of eligible enrolled patients at each time point. Patients were disenrolled if they received a heart transplant or died.

| Pre- Implant |

Immediately after implant |

2 weeks post |

4 weeks post |

12 weeks post |

24 weeks post |

36 weeks post |

48 weeks post |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression response rate | 42% (5/12) |

26% (16/62) |

42% (32/77) |

52% (43/83) |

55% (41/75) |

47% (26/75) |

88% (14/16) |

44% (7/16) |

| Anxiety Response Rate | 58% (7/12) |

24% (15/62) |

43% (33/77) |

52% (43/83) |

56% (42/75) |

49% (27/55) |

88% (14/16) |

44% (7/16) |

| Panic total response rate | N/A | N/A | 42% (32/77) |

52% (43/83) |

55% (41/75) |

45% (25/55) |

88% (14/16) |

44% (7/16) |

| ASD total response rate | N/A | N/A | 42% (32/77) |

52% (43/83) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| PTSD total response rate | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 55% (41/75) |

45% (25/55) |

88% (14/16) |

44% (7/16) |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. Vol. 29. United States: 2010. Second INTERMACS annual report: More than 1,000 primary left ventricular assist device implants; pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. Vol. 33. United States: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; 2014. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: A 10,000-patient database; pp. 555–564. All rights reserved. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein NE, May CW, Meier DE. Circ Heart Fail. Vol. 4. United States: 2011. Comprehensive care for mechanical circulatory support: A new frontier for synergy with palliative care; pp. 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelfman LP, Kalman J, Goldstein NE. J Palliat Med. Vol. 17. United States: 2014. Engaging heart failure clinicians to increase palliative care referrals: Overcoming barriers, improving techniques; pp. 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Proposed decision memo for ventricular assist devices for bridge-to-transplant and destination therapy (CAG-00432R) Washington D.C.: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Vol. 345. United States: 2001. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure; pp. 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMahon KALG. Psychological factors in heart failure: A review of the literature. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:509–516. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baba A, Hirata G, Yokoyama F, et al. J Artif Organs. Vol. 9. Japan: 2006. Psychiatric problems of heart transplant candidates with left ventricular assist devices; pp. 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro P, Levin H, Oz M. Left ventricular assist devices. psychosocial burden and implications for heart transplant programs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:30S–35S. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00076-x. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wray J, Hallas CN, Banner NR. Clin Transplant. Vol. 21. Denmark: 2007. Quality of life and psychological well-being during and after left ventricular assist device support; pp. 622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mapelli D, Cavazzana A, Cavalli C, Bottio T, Tarzia V, Gerosa G, Volpe B. Clinical psychological and neuropsychological issues with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2014:3. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.08.14. Available from: http://www.annalscts.com/article/view/4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Modica M, Ferratini M, Torri A, et al. Artif Organs. International Center for Artificial Organs and Transplantation and Wiley Periodicals, Inc; 2014. Quality of life and emotional distress early after left ventricular assist device implant: A mixed-method study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez JS, Goldraich LA, Nunes AH, et al. Arq Bras Cardiol. Vol. 106. scielo; 2016. Association between spirituality and adherence to management in outpatients with heart failure; pp. 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ader DN. Med Care. Vol. 45. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) pp. S1; S1–S2; S2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.PROMIS. Promis adult profile instruments: A brief guide to the PROMIS profile instruments for adult respondents. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. JAMA Intern Med. Vol. 173. United States: 2013. Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life; pp. 1109–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. J Clin Oncol. Vol. 25. United States: 2007. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life; pp. 555–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laird NM, Ware JH. Biometrics. Vol. 38. UNITED STATES: 1982. Random-effects models for longitudinal data; pp. 963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 9th. Philadelphia: Wolters Klower Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.RUBIN DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kop WJ, Synowski SJ, Gottlieb SS. Heart Fail Clin. Vol. 7. United States: Elsevier Inc; 2011. Depression in heart failure: Biobehavioral mechanisms; pp. 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Arch Intern Med. Vol. 161. United States: 2001. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure; pp. 1849–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havranek EP, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, Jones PG, Rumsfeld JS. J Am Coll Cardiol. Vol. 44. United States: 2004. Predictors of the onset of depressive symptoms in patients with heart failure; pp. 2333–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koenig HG. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Vol. 20. UNITED STATES: 1998. Depression in hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure; pp. 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gnanasekaran G. Heart Fail Clin. Vol. 7. United States: Elsevier Inc; 2011. Epidemiology of depression in heart failure; pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. JAMA. Vol. 276. UNITED STATES: 1996. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder; pp. 293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Vol. 62. United States: 2005. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication; pp. 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martz E, Cook DW. Physical impairments as risk factors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2001;44:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunzel B, Laederach-Hofmann K, Wieselthaler GM, Roethy W, Drees G. Transplant Proc. Vol. 37. United States: 2005. Posttraumatic stress disorder after implantation of a mechanical assist device followed by heart transplantation: Evaluation of patients and partners; pp. 1365–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberge MA, Dupuis G, Marchand A. Psychosom Med. Vol. 70. United States: 2008. Acute stress disorder after myocardial infarction: Prevalence and associated factors; pp. 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller-Tasch T, Frankenstein L, Holzapfel N, et al. J Psychosom Res. Vol. 64. England: 2008. Panic disorder in patients with chronic heart failure; pp. 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein NE, May CW, Meier DE. Circ Heart Fail. Vol. 4. United States: 2011. Comprehensive care for mechanical circulatory support: A new frontier for synergy with palliative care; pp. 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]