Abstract

The stepfamily literature is replete with between-group analyses by which youth residing in stepfamilies are compared to youth in other family structures across indicators of adjustment and well-being. Few longitudinal studies examine variation in stepfamily functioning to identify factors that promote the positive adjustment of stepchildren over time. Using a longitudinal sample of 191 stepchildren (56% female, mean age = 11.3 years), the current study examines the association between the relationship quality of three central stepfamily dyads (stepparent-child, parent-child, and stepcouple) and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems concurrently and over time. Results from path analyses indicate that higher levels of parent-child affective quality are associated with lower levels of children’s concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems at Wave 1. Higher levels of stepparent-child affective quality are associated with decreases in children’s internalizing and externalizing problems at Wave 2 (6 months beyond baseline), even after controlling for children’s internalizing and externalizing problems at Wave 1 and other covariates. The stepcouple relationship was not directly linked to youth outcomes. Our findings provide implications for future research and practice.

Keywords: children, child adjustment, family processes, family relationships, stepfamily

Stepfamilies are one of the fastest growing family forms in the United States. A stepfamily is formed when one or both adults in a new committed relationship bring with them a child or children from a previous relationship (Ganong & Coleman, 2004). Nearly one-third of all children live in a stepfamily household before reaching adulthood (Bumpass, Raley, & Sweet, 1995; Pew Research Center, 2011).

Despite increasing ubiquity, stepfamilies generally face a number of stressors not experienced by members of biological nuclear families. This is attributable, in part, to the lack of legal and social clarity surrounding stepfamily relationships and roles (Coleman, Ganong, & Russell, 2013). Common stepfamily stressors include shifts in the quality of parent-child relationships, conflicting family cultures and expectations, family boundary ambiguity, stepparenting issues, uncertainty among children about how new stepparents should fit into their lives, and co-parental conflict (Jensen & Shafer, 2013; Jensen, Shafer, & Larson, 2014; Pace, Shafer, Jensen, & Larson, 2013; Papernow, 2013; van Eedeen-Moorefield & Pasley, 2013). Processes associated with parental divorce (e.g., loss of contact with one parent, declines in parental support, loss of emotional support, conflict between ex-spouses) and other precursory family transitions may exacerbate stepfamily stress (Amato, 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991; Coleman et al., 2013; Shafer, Jensen, & Holmes, 2016).

Although most children fare well in stepfamilies, children in stepfamilies are at an elevated risk of experiencing adjustment problems (Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998), and efforts to identify factors that promote stepfamily functioning and child adjustment are warranted. Yet, most studies to date focus on stepfamily deficits, examine single protective relationships (e.g., parent-child) cross-sectionally, and incorporate samples with primarily young or adolescent children. The expansion of knowledge in this area can inform the development and adaptation of programs, policies, and other interventions aimed at helping children in stepfamilies thrive. Drawing on past research and theory, the purpose of this study is to assess the extent to which the quality of three central stepfamily relationships—stepparent-child, parent-child, and stepcouple—is associated with the adjustment of stepchildren concurrently and over time during the transition to adolescence.

Children’s Adjustment in Stepfamilies

The increasing prevalence of stepfamilies, a growing awareness of stepfamily challenges, and concern for children’s well-being led to an emergence of between-group analyses by which family scholars assessed how members of stepfamilies differed from members of other family types, often biological nuclear families, with respect to adjustment (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman, Ganong, & Fine, 2000). Findings from nationally representative studies and meta-analyses indicate that children in stepfamilies are at an elevated risk of experiencing maladjustment in terms of academic, social, behavioral, and psychological well-being (Hoffman, 2002, 2006; Jeynes, 2006; Tillman, 2007).

Although these studies have been critical in understanding the risks associated with stepfamily life, they do not help differentiate stepfamilies from one another, or identify which characteristics may be linked to more effective adaptation among stepfamilies specifically. Given the unique stressors and demands faced by stepfamilies, more studies are needed to help understand families that are able to successfully adapt to new family structures (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Coleman et al,. 2013). Thus, family scholars have advocated for a normative-adaptive approach to stepfamily research that instead of comparing stepfamilies to biological nuclear families, focuses on understanding variation among stepfamilies specifically. Because there exists great variability in stepfamily adjustment, analyses on samples of stepfamilies can uncover factors that promote stepfamily resilience in terms of both family functioning and individual well-being (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2013). Consistent with a normative-adaptive approach, we investigate factors linked to positive youth adjustment in stepfamilies.

Family Relationships and Child Adjustment

The quality of family relationships may play a key role in promoting stepchildren’s well-being—including stepparent-child, parent-child, and stepcouple relationships. Children fare better in terms of psychological, social, and behavioral health when they perceive relationships in the family as positive, available, stable, and secure (Cummings et al., 2006; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Thus, in stepfamily contexts, children in families that maintain positive relationships may experience a greater sense of stability and support, whereas those with conflictual family relationships may experience the transition to stepfamily life as a significant loss, source of stress, and threat to their emotional security (Cummings et al., 2006; Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001).

In terms of past research, studies on both biological nuclear families and stepfamilies suggest that parent-child relationships play an important role in children’s adjustment. For example, children who perceive their parents as uncaring report higher levels of substance use and depression, and lower levels of self-esteem compared to children who feel that their parents care about them (Ackard, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Perry 2006). Parent-child connectedness and parental emotional availability are also linked to children’s emotional functioning and school performance (Boutelle, Eisenberg, Gregory, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2009; Sturge-Apple, Davies, Winter, Cummings, & Schermerhorn, 2008). Moreover, parent-child hostility is positively associated with children’s increased risk for internalizing and externalizing problems (Low & Stocker, 2005). In the context of family transitions and partnership instability, lower quality mothering and lower levels of maternal sensitivity are predictive of young children’s externalizing behavior problems (Cavanagh & Huston, 2006; Osborne & McLanahan, 2007). During the transition to stepfamily life, high-quality parent-child relationships are associated with a reduction in children’s self-reported stress (Jensen, Shafer, & Holmes, 2015).

The stepparent-child relationship may also have important implications for children’s well-being, although relatively few recent studies have examined the influence of stepparent-child relationships on children’s adjustment (Coleman et al., 2013). This gap in the literature is surprising, as the stepparent-child relationship represents the most unique feature of stepfamilies. Indeed, it is this relationship that makes a family a stepfamily in the first place. Stepparent roles are often far more ambiguous than biological-parent roles, and take on a variety of forms (Papernow, 2013). In some cases, stepparents and children foster a relationship over time that is unique and beneficial as stepparents enter into an “intimate outsider” mentoring role for their stepchildren (Papernow, 2013, p. 160). Stepparent-child closeness is negatively associated with higher risk for internalizing, externalizing, and academic problems among adolescents in stepfamilies (King, 2006). High-quality stepparent-child relationships have also been linked to lower levels of children’s self-reported stress amid the transition to stepfamily life (Jensen et al., 2015). Because most studies on stepfamilies have been cross-sectional (Coleman et al., 2000), we know little about how stepfamily processes are linked to youth adjustment over time.

The quality of the interparental relationship has also been linked to children’s adjustment, although most studies have focused on biological nuclear families. Children and adolescents who are exposed to interparental conflict are more likely to perceive it as threatening to their well-being or that of the family, which in turn is a key risk factor for internalizing problems (Fosco & Feinberg, 2015; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Grych, Harold, & Miles, 2003). Interparental conflict is often even more threatening to youth who have witnessed violence or experienced divorce in the past (Grych, 1998). Another perspective focuses on the spillover of hostility from interparental to parent-child relationships (e.g., Erel & Burman, 1995). Indeed, high levels of conflict between parents is related to greater adolescent-parent hostility (Fosco, Lippold, & Feinberg, 2014), as well as less warmth and lower quality parenting (Benson, Buehler, & Gerard, 2008). High levels of conflict between parents can also spillover into parent-child relationships—a process identified as a risk factor for child maladjustment (Fosco, Lippold, Feinberg, 2014). Thus, the quality of couple relationships can exert influence on children’s adjustment directly, via exposure to emotionally charged interactions between parents, and indirectly, via shifts in parenting practices and declines in parental emotional availability (Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2006; Troxel & Matthews, 2004). We note that little is known about links between stepcouple relationship quality and children’s adjustment over time.

Although previous theory and a limited body of research has linked familial factors to stepchild adjustment, existing studies tend to focus on the impact of single dyadic relationships (e.g., King, 2006; refer to Nicholson, Sanders, Halford, Phillips, & Whitton, 2008 for an overview). Very few studies have examined the influence of stepparent-child, parent-child, and stepcouple relationships on youth adjustment in a single model (see Hetherington, Henderson, & Reiss, 1999 for a notable exception). Thus, we lack a firm understanding of which stepfamily dyads exert the most influence on children’s adjustment in stepfamilies.

Family systems theory posits that the entire family system, along with its interconnected subsystems, can influence the well-being of a single system member (Cox & Paley, 1997; Minuchin, Nichols, & Lee, 2007; Robbins, Chatterjee, & Canda, 2012). Indeed, clinical experts have noted the importance of exploring the context in which individual-level symptoms appear. A proper exploration of stepfamily contexts and youth adjustment should include a wide range of dyadic relationships, including dynamics within stepparent-child, parent-child, and stepcouple relationships.

Moreover, the Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response (FAAR) Model highlights the importance of family capabilities, including psychosocial resources such as high-quality family relationships, that can help families face their demands and stressors, even those induced by the transition to stepfamily life (Patterson, 2002). Family adjustment is optimized when family capabilities exceed family demands. Evidence of family adjustment includes the extent to which families are able to carry out key functions, such as the promotion of children’s physical, social, and psychological health and development. Both family systems theory and the FAAR model call for the inclusion of numerous dyadic relationships when examining the influence of stepfamily processes, such as relationship quality, on children’s adjustment.

An understanding of which dyadic relationships and processes are most influential in terms of youth adjustment can guide the development of effective stepfamily interventions. Because change in youths’ levels of stress and perceived levels of parental support is one key mechanism that links family processes to youth adjustment (Sheeber et al., 2001), youth adjustment might be most closely tied to parent-child and stepparent-child relationship quality. Indeed, processes and interactions between youth and their parental figures are the most proximal source of adolescents’ perceived support or interpersonal stress (Sheeber et al., 2001). On the other hand, emotional security theory would highlight the prominence of the stepcouple relationship, as the nature of stepcouple interactions can hinder or bolster youths’ sense of emotional security, and as a result, influence youths’ adjustment (Cummings et al., 2006). Thus, the stepcouple relationship, although more distal, may also be linked to youth outcomes.

The Importance of Early Adolescence

Among the limited number of studies in which stepfamily processes and children’s adjustment are examined, the focus has rested primarily on adolescent stepchildren. Additional exploration of the adjustment of stepchildren during the transition to adolescence is warranted. The transition to adolescence is a developmental stage marked by significant cognitive growth and notable social transitions, such as the shift from elementary school to middle school (Charlesworth, 2015), making it an important time for research and practice aimed at bolstering children’s adjustment in stepfamilies. Indeed, early-adolescent children continue relying, to some extent, on parents and other family members to help them regulate emotions and provide social structure (Sameroff, 2010). At the same time, early adolescents begin to place emphasis on peer groups and individual autonomy (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). On the surface, adolescents’ goal of achieving autonomy might seem at odds with the goal many stepfamilies have to come together and establish family cohesiveness. Thus, developmental changes among early-adolescent children often require parents and youth to carefully renegotiate their relationship to allow for children’s growing autonomy and independence, while still maintaining positive and beneficial relationships. Although this is true among virtually all families, the successful negotiation of early adolescents’ pursuit of autonomy and the family’s desire to establish cohesion might be particularly important and nuanced in stepfamily contexts.

Overall, the early adolescent transition may be a time when stepfamily relationships are undergoing changes, and stepfamily members’ ability to successfully adapt and maintain a close relationship during these changes may have important linkages to youth adjustment. Thus, the period of time in which children begin their transition to adolescence may be a particularly beneficial time to promote stepchildren’s adjustment via protective stepfamily processes. Further, youth internalizing and externalizing problems during adolescence may have important implications over the life course: adaptive gains during early adolescence can benefit children as they continue to develop, and might prevent or buffer the development of later psychopathology (Cox, Mills-Koonce, Propper, & Gariépy, 2010).

Current Study

As informed by past research and theory, our specific aim was to examine the extent to which stepparent-child affective quality, parent-child affective quality, and stepcouple relationship quality are associated with youth adjustment. Linkages between each dyadic relationship and youth adjustment could occur concurrently or longitudinally. For example, dyadic relationships could have immediate proximal effects on youth adjustment, with poorer relationships increasing the risk of maladjustment. In addition, dyadic relationships could have more distal effects on youth adjustment. That is, associations between relationship quality and youth adjustment could occur over time, and manifest at a later time point. Given this, we examined both the proximal and distal linkages between dyadic relationship quality and youth adjustment.

Further, the distal, longitudinal associations between dyadic relationship quality and youth adjustment could occur in at least one of two ways. First, distal effects on youth adjustment might occur via concurrent youth adjustment. For example, relationships may have immediate linkages to youth adjustment, that then cumulate over time to further changes in youth adjustment at a later time point. Alternately, distal effects of relationships on youth adjustment may occur independent of concurrent influences. That is, there may be distal associations between relationship quality and youth adjustment that do not occur via concurrent changes in youth adjustment. Because of this, we also examined whether changes in concurrent adjustment mediated the distal effects of dyadic relationships on later youth adjustment.

Our measures of youth adjustment include both internalizing and externalizing problems, capturing two key domains of adjustment (Chase & Eyberg, 2008). We extend existing literature by focusing on stepfamily resilience and several key stepfamily dyads simultaneously, incorporating longitudinal analyses, and examining the influence of stepfamily relationships on children’s adjustment during early adolescence. In terms of specific hypotheses, we expect that higher levels of stepparent-child affective quality, parent-child affective quality, and stepcouple relationship quality will each be associated with lower levels of children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. As noted earlier, parent-child and stepparent-child relationships may exert greater influence than the stepcouple relationship, as parent-child relationships are more proximal social contexts for children.

Methods

Data and Sample

Our analytical sample represented 191 stepfamilies included in the in-home subsample of the Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) project. PROSPER was an effectiveness trial and diffusion of preventive interventions that targeted substance use among youth in 28 rural communities and small towns in Pennsylvania and Iowa (see Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman, & Redmond, 2004). Students from two successive cohorts of sixth graders completed in-school questionnaires. On average, 88% of all eligible students completed in-school assessments at each wave. In addition, families of students in the second cohort were randomly selected and recruited for participation in an additional in-home assessment that included a family interview, videotaping of a family interaction, and written questionnaires completed independently by the youth, mother, and, if present, father. Of the 2,267 families recruited for in-home family assessments, 977 (43%) completed the in-home assessments at Wave 1.

Given the aims of our secondary data analysis, our sample was limited to the 191 families who completed the in-home assessment and identified as stepfamilies at Wave 1. Data from in-home assessments at both Wave 1 and Wave 2 (six months later) were used. We note that no descriptive information about youths’ relationships with non-resident biological parents was available. Fifty-six percent of the sample included families with female children, and 93% of youth were identified as being White (the remaining 6% of the sample was identified as being Hispanic-Latino, African American, Asian, or other). The average youth age was 11.30 years (SD = .49 years), and ranged from age 10 to 12 (i.e., early adolescence). Nearly 90% of the youth in the analytical sample resided with a biological mother and stepfather (n = 171); the remaining 10% resided with a biological father and stepmother (n = 20). The majority of stepfamilies (82%) were formed following parental divorce. In terms of parental marital status, 65% of the stepcouples were married versus cohabiting. The average number of household residents (i.e., individuals residing in the home 50% or more of the time) was 4.84 (SD = 1.18), and the average household income was $45,703 (SD = $29,697) at Wave 1 (2003). Refer to Table 1 for more details.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Stepfamily Subsample at Wave 1 (N = 191)

| n or mean | % or SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Stepfamily Characteristics | ||

| Stepfamily Type | ||

| Mother, Stepfather | 171 | 89.5% |

| Father, Stepmother | 20 | 10.5% |

| Parental Marital Status | ||

| Married | 125 | 65.4% |

| Cohabiting | 61 | 31.9% |

| Number of household members living in home (50% or more of the time) | 4.84 | 1.18 |

| Household Income (Dollars) | 45,703 | 29,697 |

| Stepfamily Formed After Parental Divorce | ||

| Yes | 156 | 81.7% |

| No | 31 | 16.2% |

| Intervention Condition | ||

| Intervention Group | 108 | 56.5% |

| Control Group | 83 | 43.5% |

| Focal Youth Characteristics | ||

| Biological Sex | ||

| Female | 107 | 56.0% |

| Male | 84 | 44.0% |

| Racial/Ethnic Identity | ||

| White | 177 | 92.7% |

| Hispanic-Latino | 6 | 3.1% |

| African-American | 1 | 0.5% |

| Asian | 2 | 1.0% |

| Other | 4 | 2.1% |

| Age | 11.30 | 0.49 |

| Number of Stepsiblings | 0.26 | 0.67 |

Measures

Internalizing problems

Internalizing problems at Wave 1 and Wave 2 were measured using a 14-item scale from the Youth Self Report of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) that assessed adolescent depression and anxiety using items such as, “I am unhappy, sad, or depressed”, and “I worry a lot”. Response options ranged from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true), and items were averaged into an internalizing problems score (α = .88).

Externalizing problems

Externalizing problems at Wave 1 and Wave 2 were measured using a 25-item scale from the Youth Self Report of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) that assessed adolescent aggressive behavior using items such as, “I destroy things” and “I disobey my parents.” Response options ranged from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true), and items were averaged into an externalizing problems score (α = .87).

Stepparent-child affective quality

All parenting measures were adapted from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (Conger, 1989; McMahon & Metzler, 1998; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 1998). Stepparent-child affective quality (α = .76) was a 7-item composite scale. The items asked children to indicate how often during the past month a stepparent exhibited the following positive or negative affective behaviors: got angry at them; let them know she/he really cared about them; let them know that she/he appreciated them, their ideas, or the things they did; acted loving and affectionate toward them; shouted or yelled at them because she/he was mad at them; insulted or swore at them; lost her/his temper and yelled at them when the child did something wrong. Response options ranged from 1 (always) to 7 (never), and all items were coded such that higher values indicated greater stepparent-child affective quality.

Parent-child affective quality

Parent-child affective quality (α = .71) consisted of the same seven items as the stepparent-child affective quality scale, to which children indicated the frequency of their biological parents’ positive or negative affective behavior. Items were coded such that higher values indicated greater parent-child affective quality.

Stepcouple relationship quality

Stepcouple relationship quality (α = .92) was an 11-item composite scale. The items asked biological parents to indicate how often during the past month their partners: got angry at them; let them know she/he really cares about them; criticized them or their ideas; let them know that she/he appreciates them, their ideas, or the things they do; help them do something that was important to them; hit, pushed, grabbed, or shoved them; acted loving and affectionate toward them; argued with them whenever they disagreed about something; shouted, yelled, or screamed at them; swore or cursed at them; called them dumb or lazy or some other name like that. Response options ranged from 1 (always) to 7 (never), and all items were coded such that higher values indicated greater stepcouple relationship quality.

Covariates

We included the following covariates in our analyses: youth biological sex (0 = female, 1 = male), stepparent’s biological sex (0 = stepfather, 1 = stepmother), pre-stepfamily parental divorce (1 = divorce did not precede stepfamily formation [death of a parent or non-marital childbearing preceded the transition to stepfamily life], 0 = parental divorce preceded stepfamily formation), intervention condition (0 = control condition, 1 = intervention condition), parental marital status (1 = stepcouple is cohabiting, 0 = stepcouple is married), parents’ education attainment (continuous measure of average years of education between parents and stepparents), and number of stepsiblings (continuous measure).

Analysis Strategy

We employed longitudinal path analyses in Mplus 7.4 to examine associations between stepfamily relationship constructs and youth adjustment outcomes. One model was estimated in which the quality of dyadic relationships was associated with youth adjustment, both concurrently (at Wave 1) and longitudinally (at Wave 2). The youth adjustment variables at both waves were specified as endogenous and regressed on seven covariates—youth biological sex, stepparent’s biological sex, pre-stepfamily parental divorce, intervention condition, parental marital status, parents’ educational attainment, and number of stepsiblings. Thus, the association between one dyadic relationship and youth adjustment at Wave I was net the influence of covariates and each of the other dyadic relationships. Youth adjustment variables at Wave 2 were also regressed on youth adjustment variables at Wave 1. Thus, parameters associated with Wave 2 adjustment outcomes reflect change scores from Wave 1 to Wave 2. If a relationship-quality construct was significantly associated with youth adjustment at Wave 1 but not at Wave 2, we conducted tests of indirect effects between the relationship-quality construct and youth adjustment at Wave 2 via youth adjustment at Wave 1—a possible indication of a cascading effect.

The following model fit indices were used to indicate acceptable model fit: a non-significant chi-square statistic, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) values of greater than .95, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of less than or equal to .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Preliminary calculations indicated that the path models were over-identified. We used maximum likelihood estimation (ML) to estimate model parameters. Missingness ranged from 0 to 15% for each variable, and preliminary analyses provided evidence that missing data sufficiently met the MAR assumption (Enders, 2010). Thus, we used full-information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data.

Results

Table 2 displays bivariate correlations between key study variables. Stepparent-child affective quality was negatively correlated with youth internalizing and externalizing concurrently and over time. Parent-child relationship quality was negatively correlated with youth internalizing concurrently and youth externalizing concurrently and over time. Stepcouple relationship quality was negatively correlated with only concurrent levels of both youth internalizing and externalizing.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Substantive Variables (N = 191).

| Variable | Obs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Internalizing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1) Wave 1 | 191 | 0.25 | 0.27 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2) Wave 2 | 162 | 0.21 | 0.29 | .42 | * | |||||||||||||||||||

| Youth Externalizing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3) Wave 1 | 191 | 0.19 | 0.20 | .63 | * | .41 | * | |||||||||||||||||

| 4) Wave 2 | 163 | 0.19 | 0.25 | .28 | * | .69 | * | .56 | * | |||||||||||||||

| Independent Variables (Wave 1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5) Stepparent-Child Affective Quality | 182 | 5.62 | 1.21 | −.27 | * | −.21 | * | −.31 | * | −.27 | * | |||||||||||||

| 6) Parent-Child Affective Quality | 191 | 5.82 | 0.87 | −.30 | * | −.09 | −.35 | * | −.18 | * | .54 | * | ||||||||||||

| 7) Stepcouple Relationship Quality | 184 | 5.64 | 0.94 | −.15 | * | −.12 | −.14 | * | −.06 | .32 | * | .20 | * | |||||||||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8) Youth Biological Sex | 191 | −.01 | −.01 | .16 | * | .10 | −.04 | −.03 | −.11 | |||||||||||||||

| 9) Stepparent Biological Sex | 191 | .06 | .02 | .10 | .08 | −.11 | .06 | .00 | −.10 | |||||||||||||||

| 10) Pre-Stepfamily Divorce | 187 | −.03 | .10 | .04 | .03 | .00 | .02 | −.07 | .06 | −.10 | ||||||||||||||

| 11) Intervention Condition | 190 | .10 | −.06 | .10 | −.09 | .02 | −.13 | −.02 | .02 | −.06 | −.07 | |||||||||||||

| 12) Parents' Marital Status | 186 | −.05 | −.13 | .02 | −.02 | .07 | .08 | .00 | .11 | .12 | .07 | −.07 | ||||||||||||

| 13) Parents’ Educational Attainment | 188 | 12.88 | 1.67 | −.03 | −.01 | −.08 | −.08 | .11 | .10 | −.01 | .15 | * | .06 | .12 | −.01 | .07 | ||||||||

| 14) Number of stepsiblings | 191 | 0.26 | 0.69 | .06 | .11 | .11 | .21 | * | −.06 | .02 | −.09 | −.03 | .02 | .02 | −.01 | −.18 | * | −.06 |

Note:

p < .05.

Youth Internalizing

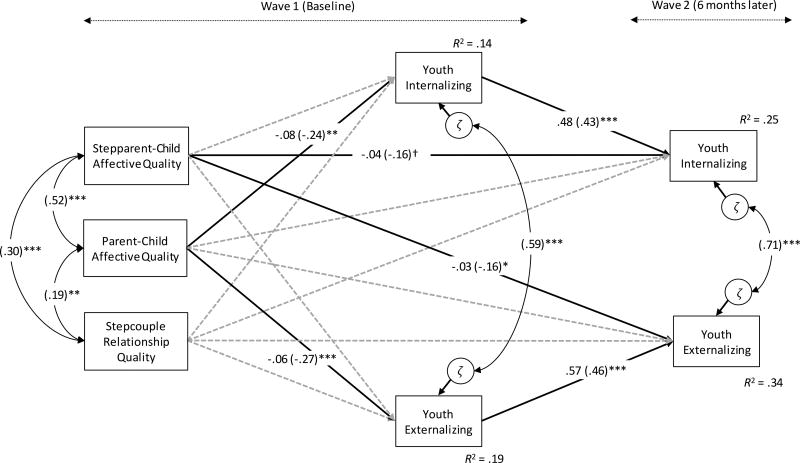

Figure 1 displays the results associated with our hypothesized model. Model fit indices were as follows: χ2(23) = 30.64, p = .13; CFI = .98; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .04 (90% confidence interval: .00, .08), all indicating acceptable model fit based on pre-specified criteria. The model explained 14% of the variance in youth internalizing at Wave 1 and 25% of the variance in youth internalizing at Wave 2.

Figure 1. Longitudinal Path Analyses of Youth Internalizing and Externalizing and Stepfamily Relationship Quality Constructs.

Note: †p ≤ .10; *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001. Standardized path coefficients are in parentheses. Maximum Likelihood estimation was used. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines. Model fit indices are as follows: χ2(23) = 30.64, p = .13; CFI = .98; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .04, 90% confidence interval [.00, .08]. Covariates: child's biological sex, stepparent's biological sex, pre-stepfamily parental divorce, intervention condition, parental marital status, parents' educational attainment, and number of stepsiblings.

In terms of structural path coefficients, stepparent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was negatively associated with youth internalizing problems at Wave 2 (b = −.04, p = .066, β = −.16), while controlling for Wave 1 youth internalizing problems and other covariates. Because youth adjustment outcomes at Wave 2 represent change scores (Wave I adjustment outcomes are controlled for), stepparent-child affective quality was significantly associated with change in youth internalizing over time. Parent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was negatively associated with concurrent youth internalizing problems at Wave 1 (b = −.08, p < .01, β = −.24). As indicated by tests of indirect effects, parent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was also indirectly associated with youth internalizing at Wave 2 via youth internalizing at Wave 1 (b = −.04, p < .01, β = −.10). The quality of the stepcouple relationship was not associated with internalizing problems at either Wave 1 or Wave 2, but was correlated with parent-child and stepparent-child affective quality (r = .19 and r = .30, respectively).

Youth Externalizing

In terms of youth externalizing problems, the model explained 19% of the variance in youth externalizing at Wave 1 and 34% of the variance in youth externalizing at Wave 2. Stepparent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was associated with Wave 2 youth externalizing problems (b = −.03, p < .05, β = −.16), while controlling for Wave 1 youth externalizing problems and other covariates. This indicated that stepparent-child affective quality was significantly associated with change in youth externalizing problems over time. Parent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was associated with concurrent youth externalizing problems at Wave 1 (b = −.06, p < .001, β = −.27). As indicated by tests of indirect effects, parent-child affective quality at Wave 1 was also indirectly associated with youth externalizing problems at Wave 2 via youth externalizing problems at Wave 1 (b = −.04, p < .01, β = −.13). The quality of the stepcouple relationship was not associated with externalizing problems at either Wave 1 or Wave 2, but was correlated with parent-child and stepparent-child affective quality (r = .19 and r = .30, respectively). Refer to the Appendix for more details pertaining to model parameters.

Appendix.

All Model Parameters

| Youth Internalizing | Youth Externalizing | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Variable | b | SE | p-value | β | b | SE | p-value | β | b | SE | p-value | β | b | SE | p-value | β | ||||

| Youth Internalizing (Wave 1) | 0.48 | 0.07 | *** | 0.00 | 0.43 | |||||||||||||||

| Youth Externalizing (Wave 1) | 0.57 | 0.07 | *** | 0.00 | 0.46 | |||||||||||||||

| Stepparent-Child Affective Quality | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.18 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.02 | † | 0.07 | −0.16 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.15 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.02 | * | 0.05 | −0.16 | ||

| Parent-Child Affective Quality | −0.08 | 0.03 | ** | 0.00 | −0.24 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.02 | *** | 0.00 | −0.27 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.08 | ||

| Stepcouple Relationship Quality | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.27 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.08 | ||||

| Youth Biological Sex | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Stepparent Biological Sex | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.30 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.05 | * | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.67 | |||||||

| Pre-Stepfamily Divorce | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.36 | ||||||||

| Intervention Condition | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.29 | −0.09 | 0.04 | † | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.32 | −0.07 | 0.03 | * | 0.03 | ||||||

| Parents' Marital Status | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.69 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.67 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.78 | ||||||||

| Parents’ Educational Attainment | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.37 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.41 | −0.06 | ||||

| Number of stepsiblings | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.17 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Correlation Matrices | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stepparent-Child Affective Quality | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Parent-Child Affective Quality | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stepcouple Relationship Quality | 0.30 | 0.19 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| Youth Internalizing (Wave 1) | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Youth Externalizing (Wave 1) | 0.59 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Youth Internalizing (Wave 2) | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Youth Externalizing (Wave 2) | 0.71 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

Note:

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

All correlations were significant at p ≤ .01. b = unstandardized coefficient. β = standardized coefficient. Standardized coefficients are only displayed for continuous variables.

Homogeneity of Results

Because we conducted a secondary analysis of data collected in an intervention trial, we wanted to assess whether our model performed differently between families in the intervention or control groups. Whereas the intervention might be expected to influence mean levels of the constructs in our models (which we handled by including the intervention condition as a covariate), we did not expect it to exert influence on the magnitude of associations between constructs (i.e., moderation). Thus, we tested the invariance of model paths between families in the intervention and control groups by comparing the fit of the model where all paths were constrained to be equal between groups to a model where all paths were freely estimated, including stability parameters (i.e., paths between youth outcomes from Wave 1 to Wave 2). Results indicated that there was not a significant difference in model fit (Δχ2 = 52.696, df = 41, p = n.s.), suggesting that all model paths were statistically indistinguishable between groups (i.e., intervention condition did not moderate the magnitude or significance of model paths). We concluded that the relations among our study variables were equivalent across intervention conditions and we present findings on the full sample.

Test of Alternative Model

Previous research has highlighted the possibility of bidirectional associations between youth adjustment and stepfamily relationship quality (King, Amato & Lindstrom, 2015), such that youth adjustment might predict the quality of relationships just as the quality of relationships might predict youth adjustment. To bolster our confidence in our model specification (which did not specify bidirectional associations), we tested an alternative model in which relationship-quality constructs at Wave 2 were added and bidirectional associations between relationship quality and youth adjustment were analyzed. Results yielded (a) the same general findings as the original model, (b) worse relative fit per model information criteria (i.e., Akaike Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC], and adjusted BIC), and (c) nonsignificant associations between youth adjustment indicators at Wave 1 and relationship-quality constructs at Wave 2. Thus, we retained our original model for interpretation and discussion.

Discussion

Stepfamilies are an increasingly common context in which children develop. Members of stepfamilies experience demands that place children at an elevated risk of experiencing adjustment problems (Hetherington et al., 1998). As a consequence, stepfamily scholars have advocated for a normative-adaptive perspective by which researchers study variation within stepfamilies to identify factors that promote children’s adjustment in this unique context (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000). Few studies have examined the influence of central stepfamily relationships on youth outcomes, and even fewer studies have examined these associations over time. Building on prior work, the purpose of this study was to examine associations between stepfamily relationship quality and youths’ adjustment during early adolescence.

Consistent with our hypotheses and previous work (Cavanagh & Huston, 2006; Osborne & McLanahan, 2007; Jensen et al., 2015), we found that parent-child affective quality was negatively associated with concurrent levels of both internalizing and externalizing problems in children. Thus, positive parent-child relationships represent an important psychosocial resource for children in stepfamilies. Children likely retain a sense of support amid the transition to stepfamily life when their relationship to the resident biological parent remains positive and of high quality (Jensen & Shafer, 2013; Jensen et al., 2015), a dynamic that may be associated with fewer concurrent internalizing and externalizing problems. The significant indirect association between parent-child affective quality and youth adjustment at Wave 2 via youth adjustment at Wave 1 might simply highlight a cascading effect; however, the parent-child relationship was not directly related to changes in youth adjustment over time, suggesting that most of their direct effects may occur early—during or prior to Grade 6. Because parent-child relationships predate stepparent-child relationships, the timing of their influence may be earlier than those of stepparents. The parent-child relationship may be stable and consequently less influential than the stepparent-child relationship in terms of change in youth adjustment over time.

More striking was the negative association between stepparent-child affective quality and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems over time. Stepparents who engage their stepchildren with love, affection, and appreciation, and avoid the expression of anger and aggression, are capable of providing support and exerting positive influence on children’s adjustment over time. Positive stepparent-child relationships might also buffer stress associated with common stepfamily challenges (Jensen et al., 2015). The process of developing the stepparent-child relationship certainly takes time, even in the best of cases (Papernow, 2013). Relationship development might be particularly gradual when involving stepchildren in early adolescence (Jensen & Howard, 2015).

Although our findings match those of previous studies (i.e., King, 2006), our study extends previous work by linking stepparent-child relationship quality to child adjustment across time. Because stepparents represent a novel and dynamic addition to pre-existing family relationships, it may be that the stepparent-child relationship makes a unique and important contribution to children’s adjustment over time, above and beyond the influence of the parent-child relationship, particularly during early adolescence. Also, because the entrance of a stepparent can induce additional family demands and stressors, a high-quality stepparent-child relationship may be a valuable psychosocial resource that helps stepfamilies and children adapt well to structural and other changes. We also note that stepparent-child affective quality had more variability than the other relationship variables, which may have made it more likely that we would detect associations with youth outcomes. Stepparent-child affective quality also had a slightly lower mean than the other relationship variables, possibly reducing the likelihood of ceiling effects. These features may help explain why stepparent-child affective quality was a more robust longitudinal predictor than the other stepfamily relationships.

We found no significant link between stepcouple relationship quality and children’s adjustment, either concurrently or over time. Thus, parent-child and stepparent-child interactions, and the support or stress associated with them, might be more salient for children in our sample than the quality of the stepcouple relationship. This finding matches our expectation that stepcouple relationships would be less influential than more proximal parent-child and stepparent-child relationships. Although stepcouple relationship quality is undoubtedly linked to stepfamily stability, our findings suggest that the nature of parent-child and stepparent-child relationship is more strongly linked to children’s adjustment than the quality of the stepcouple relationship, at least during early adolescence. Perhaps conflict between resident and nonresident biological parents exerts greater influence on youth adjustment than interactions between resident parents and stepparents. Alternatively, youth might be preoccupied with the navigation and development of their relationship with a new stepparent, making stepcouple interactions more peripheral with respect to youths’ stress and adjustment. Indeed, the stepparent-child relationship is what makes a family a stepfamily, and this relationship represents a notable shift in the family system to which youth must adjust. The nonsignificant association between stepcouple relationship quality and youth adjustment outcomes could also reflect a measurement artifact, as biological parents reported on the stepcouple relationship and youth reported on all of the other key variables in our model. Thus common-method variance may have influenced the strength or weakness of these associations. We also want to point out the possibility that associations between stepfamily relationships and child outcomes look different among children in other developmental stages (e.g., early childhood, adolescence; Sameroff, 2010).

Consistent with a family systems perspective, we also note that stepcouple relationship quality and the quality of parent-child and stepparent-child relationships are all positively interrelated, such that gains in one relationship can promote gains in the others (Ganong & Coleman, 2004; Jensen & Shafer, 2013; King, Thorsen, & Amato, 2014). Thus, there may be other linkages, such as indirect or mediating relationships between couple relationships, parenting, and youth outcomes that were not captured in this study.

In the context of the FAAR model, parent-child affective quality and stepparent-child affective quality are notable psychosocial resources that may help stepfamilies face demands and function more optimally to promote the development of children (Patterson, 2002). Further, our findings are compatible with the an attachment perspective, such that children are capable of experiencing gains in psychological and behavioral health as a result of perceiving their relationships with parents and stepparents as emotionally positive, rewarding, and engaging (Cummings et al., 2006; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Limitations and Future Research

The results of the current study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Other important variables, such as stepfamily duration and information about the relationship between youth and non-resident biological parents, were not available for our analyses. Also, similar to many studies in the stepfamily literature (see Jensen & Howard, 2015; Sweeney, 2010; van Eeden-Moorefield & Pasley, 2013), our sample was comprised of primarily White stepfamilies making it challenging to generalize our findings to those who identify with other racial/ethnic groups; however, the sample was representative of the rural population in which the data were collected (i.e., rural Iowa and Pennsylvania). Because our data came from an intervention study, we controlled for intervention condition as a covariate of all endogenous variables in our model. We also tested the invariance of structural parameters between those exposed and not exposed to the intervention. However, there is a possibility that intervention affected our findings in additional ways that were not captured in our analysis.

Associations between variables at Wave I should be interpreted with caution, as the temporal order of these variables cannot be determined with confidence. For example, at Wave I it is unclear from these analyses whether stepfamily relationship quality predicts youth adjustment or youth adjustment predicts stepfamily relationship quality. Although influence between stepfamily relationships and youth adjustment is likely bidirectional (e.g., King et al., 2015), we relied upon theory and past research to guide our decisions with respect to the direction of structural paths between variables measured at the same point in time. Further, the linkages between stepfamily relationships at Wave 1 and youth adjustment at Wave 2 account for youth adjustment at Wave 1, increasing our confidence that these results are not fully explained by pre-existing youth behavior. The results from a test of an alternative model in which bidirectional associations between youth adjustment and relationship-quality constructs were estimated also strengthen our confidence in our specified model. Future longitudinal work could build on our study by incorporating three or more waves of outcome data, which would provide an even clearer picture of longitudinal associations between relationship quality and youth adjustment (Collins, 2006). In addition, our sample size was relatively small, increasing the probability that truly significant associations were found to be non-significant (i.e., Type II error). There were also too few stepmother families to allow for informative group comparisons between stepfather families and stepmother families. Instead, we included stepparent sex as a covariate in our models. Because stepfamily dynamics and experiences can be gendered, future studies should incorporate data sets with a larger number of both stepmother and stepfather families so that gendered differences can be examined properly.

Despite limitations, our study extends the existing literature by drawing attention to stepfamily processes that may promote the adjustment of children in early adolescence. Our use of longitudinal data also marks an important departure from previous research. In our study, we were able to control for youth internalizing and externalizing problems at Wave 1, expanding our understanding of how stepfamily relationships may be linked to changes over time in children’s outcomes (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). By assessing three key stepfamily dyads simultaneously, we were also able to explore which dyadic relationships appear to be most influential over time in terms of stepchildren’s internalizing and externalizing during early adolescence.

We offer several suggestions for future research. Researchers should examine associations between stepfamily relationship quality and child adjustment within a larger, more representative sample of stepfamilies. Indeed, the influence of family structure and processes on children’s adjustment can operate differently across families with various racial/ethnic identities (Adler-Baeder et al., 2010). A larger sample would also enable investigators to examine measurement and structural path differences between members of stepfather families and members of stepmother families. The influence of other stepfamily relationships, such as between co-parents and between children and their siblings, stepsiblings, non-resident parents, and other extended kin, is also worthy of additional investigation, particularly with longitudinal data (Hetherington & Elmore, 2003). Ongoing use of longitudinal data would also allow researchers to continue exploring bidirectional or transactional associations between stepfamily processes and youth adjustment over multiple points in time.

Finally, this study examined stepcouple relationship quality as a direct predictor of youth adjustment, as is appropriate with two time points (e.g., Cole & Maxwell, 2003). However, stepcouple relationship quality may impact youth adjustment indirectly through parent-child and stepparent-child relationship quality. Thus, models that examine spillover processes are warranted (e.g., Benson et al., 2008; Erel & Burman, 1995). In addition, drawing on cognitive (e.g., Grych & Fincham, 1990) or emotional security perspectives (e.g., Cummings et al., 2006), it may be valuable to include youths’ subjective evaluations of parental relationship quality (e.g, threat appraisals) as an additional mechanism by which the stepcouple relationship may impact their psychological adjustment. All in all, future work exploring additional risk pathways (e.g., appraisals) or indirect factors (e.g., couple relationship quality) may further illuminate a more complete picture of stepfamily functioning and its impact on youth well-being.

Practical Implications

Because it is increasingly likely that practitioners will encounter children residing in stepfamily households, our findings have meaningful practical implications. Consistent with the tenets of structural family therapy, children who exhibit adjustment problems should be viewed in the context of the family system and its interconnected subsystems (Minuchin et al., 2007). Children’s adjustment problems largely represent attempts to adapt to their social environment (Cox et al., 2010). Helping professionals can explore with stepfamilies the interactional patterns and inner experiences that maintain presenting problems (e.g., children’s internalizing and externalizing problems), with a particular focus on bolstering the affective quality of parents’ and stepparents’ interactions with children. Improvements in the stepparent-child relationship might be especially important for promoting children’s adjustment in stepfamilies over time during early adolescence.

The continuation of strong parent-child ties is also important for establishing and maintaining stepfamily stability and children’s adjustment (Browning & Artelt, 2012; Papernow, 2013). Papernow (2013) recommends that practitioners coach parents to increase parental warmth and attunement toward their children, particularly in the early stages of stepfamily life. It might also be helpful for parents to monitor the number of positive interactions versus negative interactions they have with their children, striving to maintain a significantly greater number of positive interactions. Clinical experts have noted that parents often feel forced to pull away from children in order to reduce the pressure of being stuck between their children and a new romantic partner (Browning & Artelt, 2012). Although the stepcouple relationship requires attention and time, practitioners should help parents maintain a close connection with their children at all stages of stepfamily life. A focus on children’s nurturance is particularly warranted because children reside in familial contexts not of their own making (Papernow, 2013). In addition to parents, stepparents may play a particularly important role in facilitating such nurturance over time.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported in part by research grants R01 DA013709 and R03 DA038685 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Additional support was given to Todd Jensen through the Chancellor’s Fellowship and a predoctoral fellowship provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376) through the Center for Developmental Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Todd M. Jensen, School of Social Work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Melissa A. Lippold, School of Social Work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Roger Mills-Koonce, Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Gregory M. Fosco, Department of Human Development and Family Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Parent–child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Baeder F, Russell C, Kerpelman J, Pittman J, Ketring S, Smith T, Stringer K. Thriving in stepfamilies: Exploring competence and well-being among African American youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):396–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(3):355–370. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Buehler C, Gerard JM. Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: Spillover via maternal acceptance, harshness, inconsistency, and intrusiveness. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:428–454. [Google Scholar]

- Boutelle K, Eisenberg ME, Gregory ML, Neumark-Sztainer D. The reciprocal relationship between parent–child connectedness and adolescent emotional functioning over 5 years. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;66(4):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning S, Artelt E. Stepfamily therapy: A 10-step clinical approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Raley RK, Sweet JA. The changing character of stepfamilies: Implications of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing. Demography. 1995;32(3):425–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, Huston AC. Family instability and children's early problem behavior. Social Forces. 2006;85(1):551–581. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth LW. Middle childhood. In: Hutchison E, editor. Dimensions of human behavior: The changing life course. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. pp. 177–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chase RM, Eyberg SM. Clinical presentation and treatment outcome for children with comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(2):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong LH. Remarriage and stepfamily research in the 1980s: Increased interest in an old family form. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(4):925–940. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, Fine M. Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):1288–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, Russell L. Resilience in stepfamilies. In: Becvar D, editor. Handbook of family resilience. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Iowa Youth and Families Project, Wave A. Report prepared for Iowa State University, Ames, IA: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Mills-Koonce R, Propper C, Gariépy JL. Systems theory and cascades in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(03):497–506. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48(1):243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77(1):132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Feinberg ME. Cascading effects of interparental conflict in adolescence: Linking threat appraisals, self-efficacy, and adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:239–252. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Emotional, cognitive, and family systems mediators of children's adjustment to interparental conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(6):843. doi: 10.1037/a0013809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Lippold M, Feinberg ME. Interparental boundary problems, parent–adolescent hostility, and adolescent–parent hostility: A family process model for adolescent aggression problems. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2014;3(3):141–155. doi: 10.1037/cfp0000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH, Coleman M. Stepfamily relationships: Development, dynamics, and interventions. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Children's appraisals of interparental conflict: Situational and contextual influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(3):437. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Harold GT, Miles CJ. A prospective investigation of appraisals as mediators of the link between interparental conflict and child adjustment. Child Development. 2003;74(4):1176–1193. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children's adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Elmore AM. Risk and resilience in children coping with their parents’ divorce and remarriage. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Henderson S, Reiss D. Adolescent siblings in stepfamilies: Family functioning and adolescent adjustment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64 doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00046. (Serial No. 259) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J. The community context of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(2):314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP. Family structure, community context, and adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(6):867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis. Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, Howard MO. Perceived stepparent–child relationship quality: A systematic review of stepchildren's perspectives. Marriage & Family Review. 2015;51(2):99–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, Shafer K. Stepfamily functioning and closeness: Children's views on second marriages and stepfather relationships. Social Work. 2013;58(2):127–136. doi: 10.1093/sw/swt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, Shafer K, Holmes E. Transitioning to stepfamily life: The influence of closeness with biological parents and stepparents on children’s stress. Child & Family Social Work. 2015 doi: 10.1111/cfs.12237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, Shafer K, Larson JH. (Step)parenting attitudes and expectations: Implications for stepfamily functioning and clinical intervention. Families in Society. 2014;95(3):213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes WH. The impact of parental remarriage on children: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review. 2006;40(4):75–102. [Google Scholar]

- King V. The antecedents and consequences of adolescents' relationships with stepfathers and nonresident fathers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(4):910–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V, Amato PR, Lindstrom R. Stepfather–adolescent relationship quality during the first year of transitioning to a stepfamily. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77:1179–1189. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V, Thorsen ML, Amato PR. Factors associated with positive relationships between stepfathers and adolescent stepchildren. Social Science Research. 2014;47:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low SM, Stocker C. Family functioning and children's adjustment: associations among parents' depressed mood, marital hostility, parent-child hostility, and children's adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(3):394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Metzler CW. Selecting parenting measures for assessing family-based prevention interventions. In: Ashery RS, Robertson EB, Kumpfer KL, editors. Drug abuse prevention through family interventions. NIDA Research Monograph 177. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver P. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S, Nichols M, Lee W. Assessing families and couples: From symptoms to systems. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, McLanahan S. Partnership instability and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(4):1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Pace GT, Shafer K, Jensen TM, Larson JH. Stepparenting issues and relationship quality: The role of clear communication. Journal of Social Work. 2015;15(1):24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Papernow P. Surviving and thriving in stepfamily relationships: What works and what doesn’t. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Pew social & demographic trends survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SP, Chatterjee P, Canda ER. Contemporary human behavior theory: A critical perspective for social work. 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development. 2010;81(1):6–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer K, Jensen TM, Holmes E. Divorce stress, stepfamily stress, and depression among emerging adult stepchildren. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0617-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4(1):19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009524626436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M, Bierman K, Redmond C. PROSPER community–university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):31–39. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013979.52796.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Direct and indirect latent-variable parenting outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: Extending a public health-oriented research base. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:385–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silk J. Parenting adolescents. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple M, Davies P, Cummings E. Hostility and withdrawal in marital conflict: Effects on parental emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):227–238. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Winter MA, Cummings EM, Schermerhorn A. Interparental conflict and children's school adjustment: The explanatory role of children's internal representations of interparental and parent-child relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(6):1678–1690. doi: 10.1037/a0013857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM. Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Tillman KH. Family structure pathways and academic disadvantage among adolescents in stepfamilies. Sociological Inquiry. 2007;77(3):383–424. [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W, Matthews K. What are the costs of marital conflict and dissolution to children's physical health? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7(1):29–57. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000020191.73542.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eeden-Moorefield B, Pasley K. Remarriage and stepfamily life. In: Peterson GW, Bush KR, editors. Handbook of marriage and the family. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 517–546. [Google Scholar]