Abstract

Objectives

To describe a family caregiver communication typology and demonstrate identifiable communication challenges among four caregiver types: Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Lone.

Data Sources

Case studies based on interviews with oncology family caregivers.

Conclusion

Each caregiver type demonstrates unique communication challenges that can be identified. Recognition of a specific caregiver type will help nurses to adapt their own communication to provide tailored support.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Family-centered cancer care requires attention to the communication challenges faced by family caregivers. Understanding the challenges among four family caregiver communication types will enable nurses to better address caregiver burden and family conflict.

Keywords: family caregiver, communication, family caregiver types, family communication patterns

Communication with families can be challenging for oncology nurses because family members may avoid communication about the illness, certain family members can be excluded from decision-making, and there is a propensity for the patient and family to hide their feelings from one another.1,2 Different communication styles among family members contribute to communication difficulties and a family member’s illness can trigger the re-emergence of previous family conflicts.3 Low-quality relationships among family members, the patient’s inability or unwillingness to express emotion, and greater family conflict all contribute to caregiver depression, suggesting that communication constraints potentially influence caregiver distress.4,5

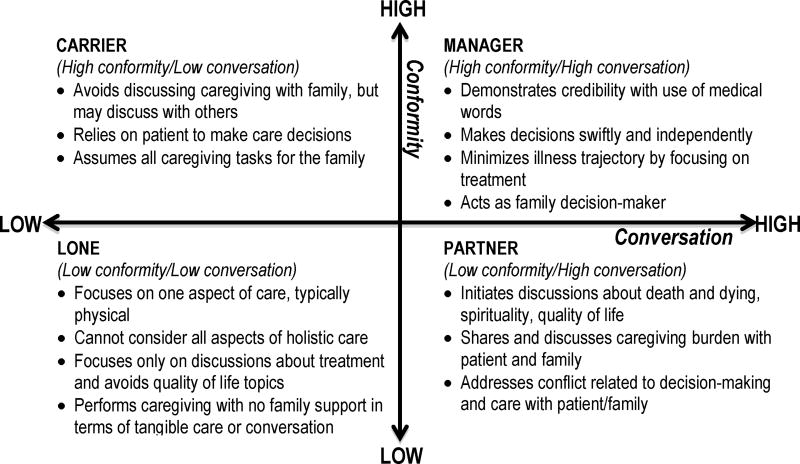

When a family member is diagnosed and treated for cancer, family communication patterns are highlighted by the illness crisis. Family communication patterns develop from implicit and explicit rules for communicating within the family system. Family rules govern appropriate topics and frequency of discussion (family conversation) and a hierarchy among family members (family conformity). Patterns of family conversation and family conformity range from high to low to form-specific communication behaviors among family members.6 Previously, we have written about four family caregiver communication types: Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Lone caregivers.3,7 Figure 1 illustrates each caregiver type based on a family communication pattern.

FIGURE 1.

Family caregiver communication typology.

Patients and caregivers share a unique relational history and thus not all family members are the same family caregiver type.2,8 The emergent caregiver type is dependent upon the relationship between the patient and the family caregiver based on communication patterns established over time within the family system. For example, a woman providing care to her mother would likely exhibit a different communication type if providing care to her sister. Among married couples, each spouse can be a different caregiver type when caring for each other.9 When asked to identify the caregiver’s communication type, our research has found that cancer patients are likely to identify the same type self-identified by the caregiver.10

Understanding family communication patterns can give insight into caregiver communication challenges related to family roles and responsibilities. This article will present a family caregiver communication typology based on family communication patterns. Each caregiver type will be illustrated through a case study analysis of an oncology family caregiver who participated in a communication coaching telephone call with an intervention nurse. Case studies are presented to depict each caregiver type and demonstrate identifiable challenges for caregivers.

Family Caregiving and Communication

The reciprocal nature of the cancer experience between patient and family caregiver has been well documented. As the patient’s cancer and treatment-specific symptoms increase, patients’ and caregivers’ distress levels also increase,11 caregiver physical and psychological health are negatively impacted,12–15 and caregivers' depression and burden increases.16 Caregiving-related health problems cause further distress within the patient-caregiver dyad17 and caregiver depression is likely to have a direct influence on patient outcomes.18–24 For instance, a patient's fear of recurrence at 3 months post-diagnosis is predictive of a caregiver’s increased distressed over time.25

Communication between caregiver and patient, family, and health care providers has a strong influence on the caregiving experience.26 Caregiver quality of life and well-being are correlated with cancer patients' perception of their care, including communication with clinical staff and care coordination.18 Family caregivers have a key communicative role in helping physicians learn about the patient and in facilitating information exchange between the doctor and the patient.27 Conflict occurs between family caregivers and staff when there is a lack of communication about advance care planning, when words are interpreted negatively and caregivers feel staff have been dismissive, and when there are different understandings regarding the disease process.28 Family environment has also been shown to influence the emotional well-being of both the cancer patient and caregiver.5 Family avoidance of cancer contributes to patient depression and anxiety,29 and low levels of communication about dying within the family and little communication during caregiving is associated with pre-loss grief symptoms.30

There is a need to further understand how caregiver distress and quality of life is impacted by the relationship between the caregiver and cancer patient.31 Caregiver burden can cause caregivers to have a decreased capacity to coordinate care, understand or recall treatment instructions, or provide emotional support to the patient.18 It is crucial to examine certain caregiving factors, such as communication and patient-caregiver expectations, which might influence patients’ and caregivers’ overall quality of life.32

Working with family caregivers presents an opportunity for oncology nurses to engage in family-centered care by tailoring and adapting their communication. Knowledge of the four different types of caregivers will aid oncology nurses in addressing caregiver burden and family communication challenges. Case studies of each caregiver type are presented to understand the unique caregiver communication challenges and distinguish appropriate nursing interventions.

Methods

The case studies presented here were selected from data collected as part of a pilot study aimed at assessing the feasibility and utility of a nurse-delivered communication coaching telephone intervention for lung cancer caregivers. Family caregivers were identified by lung cancer patients as the primary caregiver and recruited in an outpatient clinic setting in the Western United States. The Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Family caregivers were approached in the clinic and written consent was obtained. Caregivers participated in a communication coaching telephone call scheduled 1 week from study consent. Communication coaching calls were audio-recorded and transcribed. The Family Caregiver Communication Tool (FCCT) was used to determine the caregiver type upon study enrollment. The FCCT is a 10-item clinical assessment tool that measures family conversation and conformity.8 A Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (frequently) is used for each item and score interpretation is based on high (12–20) and low (0–11) cutoff points on each subscale to produce a specific caregiver type (manager, carrier, partner, lone). As part of the communication coaching call protocol, caregivers were provided a summary of all four caregiver types, informed about their type based on the FCCT, and asked to confirm the type or identify a more appropriate type.

At baseline and 1 month post coaching telephone call, caregivers completed the Caregiver Confidence in Communication survey developed by the research team to measure caregiver-reported confidence with patient, family members, and health care providers. The Caregiver Confidence in Communication survey measures the caregiver’s confidence in communicating across four specific topic areas (cancer diagnosis, cancer treatment and goal of treatment, symptom management including managing pain and side effects, and broader life topics such as spirituality and stress from caregiving). Caregivers rated their communication confidence using a Likert scale rating from 0 (not confident) to 10 (very confident).

To select case studies, we reviewed family caregivers from each type. From 20 caregivers who participated in the pilot, we selected one case for each type from those who had congruent FCCT scores and self-identified caregiver types. However, there was only one lone caregiver in the sample and that case is summarized here. In all cases caregiver names have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Results

Case 1: The Manager Caregiver

Mona is a white female, 70 years old, college-educated, and is retired. She is the primary family caregiver to her husband, Saul, who recently started treatment for lung cancer. Mona and Saul have been married 28 years and they each have two children from prior marriages. Saul’s diagnosis was sudden and Mona describes the journey: “It’s been very, very stressful for everybody because his ex-wife just died of cancer 2 years ago… and his kids are still kind of reeling from that.” She describes getting along with all the children, both his and hers, and identifies Saul’s son as the key family member she turns to for help. In her role as manager caregiver, she diligently and thoroughly follows directions set forth by the health care providers. When Saul was asked to complete an advance directive, Mona informed the research nurse, “I filed that with them downstairs last time we were there.” When reviewing suggestions for ways to talk with health care providers, Mona admitted that she had already tried all of the suggestions, including keeping a little notebook of questions and asking for copies of Saul’s medical tests to keep in her own binder. Typical of the Manager caregiver, she commonly asks for explanations for any questions she has and reports complete confidence communicating with Saul, family members, and health care providers.

As Manager caregiver, Mona is centrally concerned with prognosis: “One question I would have, and I don’t want to ask it in front of Saul, is what does she (oncologist) think the outcome is… I would like to know what, what are we looking at in reality as far as what’s happening … is it going to be 6 months or is it going to be a year?”

She describes wanting the information for herself as important, but she cautions how the information will impact Saul: “I don’t want him to be less optimistic … but reality would be good for us [she and the children] without pulling him down.” When asked if she understands what the outcomes of the treatment are supposed to be, Mona explains that she doesn’t understand but intends to discuss this with Saul: “I will, when he’s in a good mood, I will see if I can talk about that.” Mona’s desire to keep harmony and pleasantness restricts discussions about prognosis between she and Saul.

Implications for practice

While Mona reports high family conversation about the illness (“we do talk”) and a large support network (eg, friends, family), there is no real evidence of actual caregiving support. She reports communication confidence with health care providers and family members, yet conversations about treatment side effects (ie, chemo brain) and broader life topics (ie, prognosis) are difficult with Saul. The communication challenge for the Manager caregiver is the need for medical information to serve as caregiver and how to share this information, which may be upsetting, with the patient. A communication dilemma is created because sharing medical information such as treatment side effects and prognosis (high family conversation) threatens the family’s structure and roles (high family conformity). Thus, initiating a conversation about treatment side effects and prognosis with Saul is a difficult communication task for Mona.

Summary of key points

The Manager caregiver prioritizes obtaining medical information but does not necessarily have the skills for sharing subsequent information with the patient.

A focus on the social support network, described as large and comprehensive, masquerades the caregiver’s supportive resources and inability to engage in self-care.

Manager caregivers can adapt to the information systems and requirements of the health care system with ease, such as completing advance directive paperwork and following directions from health care providers.

There is a need to teach Manager caregivers how to initiate conversations with the patient in a manner that preserves and bolsters the family structure that is so valued.

Case 2: The Carrier Caregiver

Sherman is a self-employed 71-year-old white man who has been married to his wife Lena for 48 years. They have one daughter who lives about 30 miles away and three grandchildren. Last month Lena was undergoing pre-op tests for an upcoming surgery when a lesion was identified on her lung. She was later diagnosed with stage III lung cancer and started initial treatment within the last 30 days. Throughout their marriage, Sherman has relied on Lena “to take care of my business, my personal life, and everything.” Congruent with the Carrier Caregiver, Sherman is committed to serving as her caregiver: “She’s always done everything for me, and now I should step up and do a little bit more.” While he shares that they are “a close family,” Sherman reports never talking with Lena or his daughter about his wife’s illness. Sherman explains: “I gave up everything to devote to her [Lena], and it’s hard for me to ask my daughter to do anything.” As a Carrier Caregiver, Sherman relies on his wife to make all care decisions.

Since the diagnosis, he describes that Lena has become ‘short tempered’ and explains: “before she was able to cope with a lot of things, but now she’s just a little bit more frustrated.” Communication between the two of them has become difficult because Lena gives a “one word answer” and Sherman confesses that he is “afraid to ask her different questions.” He emphasizes that he can absorb his wife’s stress and is empathetic to her situation: “I say to myself, well, I know she’s stressed. I know she’s feeling that she has no control… she’s not comfortable in her body right now.” He recognizes that Lena “feels that she’s the one to carry everybody” and surmises that she is worried about who will take care of the three grandchildren when she is gone. Avoiding talk about cancer is emphasized as a way of protecting his wife from being uncomfortable with her illness: “It’s only because I don’t want to make it harder on her with what she’s going through right now…I shrug my shoulders and put my arm around her and I say ‘we’ll get through this’.”

Implications for practice

Similar to the Manager caregiver, Sherman is concerned that talk about the cancer would upset Lena. While both the Manager and Carrier caregiver have high conformity patterns, they vary in conversation patterns. Thus, Sherman and Mona have different reasons for feeling less confident about discussing broader life topics and goals of treatment with the patient. For Sherman, the Carrier caregiver, these topics would upset his wife and that would be disrespectful given all that she has done for him. On the other hand, Mona (Manager caregiver) enjoys high conversation about the disease but doesn’t discuss broader life topics that reveal changes to family structure as a result of her husband’s illness. In both instances, family harmony is prioritized – the Carrier caregiver absorbs patient stress and the enormity of caregiving tasks (“I can take it”) as part of quality caregiving, while the Manager caregiver considers high conversation to be central to caregiving tasks aimed at reducing patient stress. While both the Manager and Carrier caregivers both decline offers of supportive care services, their rationale is very different. Manager caregivers would emphasize large, open family structure and social support networks, while Carrier caregivers would emphasize their deep obligation to do it alone.

Summary of key points

Emphasis is placed on the vital role of the patient in the caregiver’s life, giving a rationale for why the caregiver will not talk about caregiving stress.

Carrier caregivers underscore their strength and ability to handle caregiving, repeatedly pointing out that they are capable of handling the patient’s psychological stress.

Explanations for the patient’s feelings (eg, anger, frustration, sadness) and empathy for the patient’s illness are frequent topics for the Carrier caregiver and used to prioritize quality patient care over caregiver self-care.

Case 3: The Partner Caregiver

Saeed is a 75 year-old Indian man and is the primary caregiver to his wife, Tala, who he has been married to for 45 years. They are both educated from an Ivy League university. Saeed is a retired engineer. They have two children and one grandchild who are regularly involved in their lives. Their daughter and their son, a physician, live several hundred miles away. Tala was diagnosed with lung cancer over 9 months ago and was given roughly 6 months or less to live. Saeed reported that ever since her diagnosis, “instead of traveling we are always home now…But, she helps me. I help her. And we talk about everything.” Both children fly in roughly every 2 weeks to attend their mother’s appointments and to assist Saeed with her care. Saeed shared that he experiences low levels of stress as Tala’s primary caregiver because they are so open about her cancer. He explains: “I think she’s the one who carries me rather than me being the caretaker….she’s the one who’s helping me… keeps my morale and enthusiasm up. She does all that for me.”

Indicative of a Partner caregiver, Saeed discusses all aspects of Tala’s health with her and their children, including the use of pain medication, tumor progression, and quality of life. With Tala’s prognosis of 6 months or less, Saeed reports that he has had no difficulty having end-oflife conversations with Tala and his two children. Family members’ opinions and concerns are taken into consideration and he explains that they “all have [their] input” into what course of action is taken for Tala’s care. While the family emphasizes quality of life as important, ultimately they respect the wishes of Tala: “My wife makes the decision of [how] she wants to proceed... [It’s] her decision, not mine… she’s aware of [the options]. All of them.” Saeed shares that he and his wife, along with their son, feel comfortable asking questions and believe they often receive straightforward answers and explanations from health care providers. He explained that having his son present at family meetings helps him to understand the options and prognosis better: “The [health care providers] communicate well, but if we miss something, my son turns around and explains to us.”

Implications for practice

Although Saeed and Tala have no family close by, their adult children remain actively involved and visit regularly. Saeed’s son, a physician, plays an integral part in supporting Saeed’s role, monitoring Tala’s medications and interpreting information from the health care team. In contrast to the Manager caregiver, who also describes open communication within the family, Saeed’s son has a specific role wherein Manager caregivers are reluctant to allow other family members to assist with unique caregiving tasks. As Tala’s tumor progresses, Saeed experiences decreased confidence in communication over time. For Saeed, communication difficulties are not about a lack of understanding about the disease or seeking prognosis information, rather, communication challenges are inherent as he embraces the final stages of Tala’s life.

Summary of key points

The patient willingly and actively serves as a major part of the caregiver’s social support network, minimizing caregiver burden by openly discussing caregiver stress with the caregiver.

Distance between family members is easily overcome by the Partner caregiver, who shares resources available through the health care system with others.

While quality-of-life issues are discussed among family members, there is an emphasis on patient dignity and respecting the patient’s decisions.

Case 4: The Lone Caregiver

Keith is Asian, 51 years old, college educated, and works full-time. He is married and has three children. Keith speaks English as a second language and is the primary caregiver, with assistance from his wife, to his father-in-law, Kai, who recently was diagnosed with lung cancer and has not yet begun treatment. Kai’s diagnosis came by surprise to his family and Keith describes the experience so far as both stressful and burdensome. Despite Kai coming from a large family, Keith repeatedly shared how he has, “no support from the family… nobody cares…it’s like [the family] tries to stay away from [Kai’s] problem.” None of his sibling-in-laws are willing to provide regular care for Kai. Keith surmised that his father-in-law “chose” him to serve as the caregiver. He explained: “I have been helping him for years.” Communication between Keith and Kai is limited: “if it is related to medical or his treatment, I tell him everything. But everything else, I just keep to myself.”

Conversations about Kai are essentially non-existent with his in-laws. Family members rarely talk about death and dying with his father-in-law or with one another and Keith has difficulty initiating such conversations with the family. He describes high caregiving burden, sharing that family members “still all rely on me… I try to bring the family together to help,” but he feels guilty doing so because “they’d never ask me for help.” Keith shared that every time he reaches out to Kai’s family to provide an update on their father: “They don’t care …They never care about anything. [My brother-in-law] said, ‘No,’ with no reason when asked if he wanted to know how his father is doing.”

Reminiscent of a Lone Caregiver, Keith shared that he had difficulty communicating about cancer. He reported low confidence in communicating symptoms, cancer pain management, and treatment side effects with his father-in-law and with his family members. He also reported having low confidence in communicating with health care providers overall and indicated he felt the least confident discussing his father-in-law’s diagnosis with them: “I feel that they are too busy or something, and even then sometimes I don’t get enough information.” Explanations regarding Kai’s treatments and prognosis are often difficult for Keith to comprehend.

Implications for practice

Across all caregiver types, the Lone caregiver reports the least confidence in communication with health care providers. Keith reports difficulty understanding and is not able to receive enough information from the health care team. The inability to understand medical information and prognosis limits Keith’s opportunities for discussions with Kai about his wishes. Communication is further obfuscated by family members who do not wish to know information about Kai’s disease. While Partner and Lone caregivers both have low family conformity, it is low family conversation that presents increased challenges for the Lone caregiver. Keith feels that he should inform his in-laws about Kai’s disease and is dismayed when they do not want to discuss it. Altogether, low conversation between Keith and health care providers, and a lack of pressure from family for information, results in limited communication about cancer overall.

Summary of key points

Despite low family conversation with other family members, the Lone caregiver and patient share communication about disease and treatment decisions.

In addition to caregiving tasks, the Lone caregiver experiences increased burden as he or she struggles to understand why other family members do not want to be involved in the care of the patient.

Lone caregivers have difficulty understanding health care providers, lowering their communication confidence and restricting the topics that they are comfortable talking about with the patient.

Discussion

Oncology nurses can support family caregivers by fostering patient–caregiver teamwork, family communication, self-care, providing information, and referring to appropriate resources.33 There is a need for caregiver assessment, education, and resources.34 Given the variance in communication patterns among family members and families in general, family members talk to each other differently. Understanding the family caregiver’s unique needs and preferences can help determine appropriate interventions.

The case studies presented here illustrate the variance in communication challenges among family caregivers. Manager and Carrier caregivers both report difficulty communicating with the patient. As a result of high family conformity, these caregiver types have a tendency to protect the patient by avoiding communication about disease and prognosis. In the case studies presented here, both caregiver types indirectly asked the research nurse about prognosis yet conveyed that they did not wish to share the information with the patient. In contrast, Partner and Lone caregivers reported no communication difficulties with the patient. In our prior work, Partner and Lone caregivers reported the lowest psychological distress, which may be a result of quality patient–caregiver communication.35 Of note, the Lone caregiver was the only caregiver type to report difficulty with health care providers.

The case studies presented here show the need for caregiver assessment, the importance of educating nurses about family caregiver types, and the unique communication challenges faced by family caregivers. The FCCT is a caregiver assessment tool that can be used to learn more about potential caregiver needs. Findings from these case studies illustrate the need to incorporate tailored communication approaches as part of family-centered care. Overall, primary communication tasks among all family caregiver types include initiating conversations about prognosis and end-of-life wishes, asking for and receiving help from others, and sharing with others the caregiver burden and need for self-care.

Our findings indicate that oncology nurses must be able to address questions posed by family caregivers and support family communication challenges. There is a need to routinely include family caregivers in cancer care. These case studies illustrate the need to provide communication training on how to identify caregiver types and provide tailored communication strategies that are in line with these specific needs. Table 1 provides a simple description of each type that can be provided to a family caregiver and Table 2 provides questions that can be asked to learn more about a caregiver’s family communication patterns. Table 3 offers suggestions for ways to support each family caregiver communication type.

TABLE 1.

Descriptions of Each Type for Family Caregivers

| Family Caregiver Type | Description Provided to Family Caregiver |

|---|---|

| Carrier | You are probably focused on doing a lot and making sure that you get everything you need from the health care providers. You likely don’t talk with others about the stress of caregiving, and you may feel very uncomfortable talking about the possibility of not finding a cure. You may have a hard time asking for or receiving help from others. |

| Partner | You are probably very comfortable accepting help from other family members. You likely are comfortable talking about how the disease has affected your family and the patient, including spiritual topics and the possibility of not finding a cure. You may have already had these conversations with your family and the patient. |

| Manager | You are probably very familiar with medical words and terminology. You are likely comfortable making decisions and acting on recommendations from health care providers. Often, you serve as the family decision-maker for the rest of the family and for the patient. |

| Lone | You are probably very focused on helping the patient and getting treatment and you worry about getting the best care possible for the patient. You may be uncomfortable talking about topics other than treatment. It may be hard for you to think about things like spirituality or how you feel about caring for the patient. You may have a hard time asking for or receiving help from others. |

TABLE 2.

Learn about Family Communication Patterns

Questions to learn about family conversation patterns

|

Questions to learn about family conformity patterns

|

TABLE 3.

Recommended Support by Caregiver Type

| Family Caregiver Type | Recommended Support for the Caregiver |

|---|---|

| Carrier |

|

| Partner |

|

| Manager |

|

| Lone |

|

Nurses can support family caregivers by teaching ways to facilitate communication in the family about cancer.30 Information about the patient’s prognosis and plan of care should be individualized to family caregiver preferences and caregivers also need support for sharing this information with other family members and, if applicable, with the patient.30 There is a need to cultivate communication skills for caregivers to empower them to advocate for the patient.36

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA33572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elaine Wittenberg, Communication Studies, California State University, Los Angeles, CA.

Haley Buller, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA.

Betty Ferrell, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA.

Marianna Koczywas, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA.

Tami Borneman, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA.

References

- 1.Friedemann ML, Buckwalter KC. Family Caregiver. J Fam Nurs. 2014;20:313–336. doi: 10.1177/1074840714532715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caughlin JP, Mikucki-Enyart S, Middelton A, Stone A, Brown L. Being open without talking about it: a rhetorical/normative approach to understanding topic avoidance in families after a lung cancer diagnosis. Commun Mono. 2011;78:409–436. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demiris G, Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. A noninferiority trial of a problem-solving intervention for hospice caregivers: in person versus videophone. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:653–660. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, Walsh M, Yonker JA. Complicated grief symptoms in caregivers of persons with lung cancer: the role of family conflict, intrapsychic strains, and hospice utilization. Omega (Westport) 2010;62:201–220. doi: 10.2190/om.62.3.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siminoff LA, Wilson-Genderson M, Baker S., Jr Depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients and their family caregivers and the influence of family environment. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1285–1293. doi: 10.1002/pon.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns theory: observations on its development and application. J Fam Commun. 2004;4:167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Oliver DP, Demiris G, Rankin A. Targeting communication interventions to decrease caregiver burden. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittenberg E, Ferrell B, Goldsmith J, Ruel NH. Family caregiver communication tool: a new measure for tailoring communication with cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1222–1224. doi: 10.1002/pon.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldsmith J, Wittenberg Lyles E, Burchett M. When patient becomes caregiver: one couple, two cases of advanced cancer. In: Brann M, editor. Contemporary case studies in health communication: theoretical and applied approaches. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company; 2015. pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldsmith J, Wittenberg E, Platt CS, Iannarino NT, Reno J. Family caregiver communication in oncology: advancing a typology. Psychooncology. 2016;25:463–470. doi: 10.1002/pon.3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badr H, Gupta V, Sikora A, Posner M. Psychological distress in patients and caregivers over the course of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oral oncology. 2014;50:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, van de Berg B, Dinant HJ, Koopmanschap MA, van den Bos GA. Burden of caregiving: evidence of objective burden, subjective burden, and quality of life impacts on informal caregivers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:570–577. doi: 10.1002/art.20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes A, While A, Mathes L. Informal carer activities, carer burden and health status in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:563–575. doi: 10.1177/0269215507075035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sautter JM, Tulsky JA, Johnson KS, et al. Caregiver experience during advanced chronic illness and last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1082–1090. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maguire R, Hanly P, Hyland P, Sharp L. Understanding burden in caregivers of colorectal cancer survivors: what role do patient and caregiver factors play? Eur J Cancer Care. 2016 Jun 8; doi: 10.1111/ecc.12527. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170:1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milbury K, Badr H, Fossella F, Pisters KM, Carmack CL. Longitudinal associations between caregiver burden and patient and spouse distress in couples coping with lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:2371–2379. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1795-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, Rowland JH. How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3554–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litzelman K, Yabroff KR. How are spousal depressed mood, distress, and quality of life associated with risk of depressed mood in cancer survivors? Longitudinal findings from a national sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:969–977. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kershaw TS, Mood DW, Newth G, et al. Longitudinal analysis of a model to predict quality of life in prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galbraith ME, Pedro LW, Jaffe AR, Allen TL. Describing health-related outcomes for couples experiencing prostate cancer: differences and similarities. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:794–801. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.794-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ejem DB, Drentea P, Clay OJ. The effects of caregiver emotional stress on the depressive symptomatology of the care recipient. Aging Ment Health. 2014;19:55–62. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segrin C, Badger TA. Psychological and physical distress are interdependent in breast cancer survivors and their partners. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:716–723. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.871304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litzelman K, Green PA, Yabroff KR. Cancer and quality of life in spousal dyads: spillover in couples with and without cancer-related health problems. Supportive Care Cancer. 2016;24:763–771. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence and psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients and their carers. Psychooncology. 2009;18:841–848. doi: 10.1002/pon.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, Schumacher K. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff JL, Guan Y, Boyd CM, et al. Examining the context and helpfulness of family companion contributions to older adults' primary care visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francois K, Lobb E, Barclay S, Forbat L. The nature of conflict in palliative care: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of staff and family members. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:1459–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong A, Shin DW, Kim SY, et al. The effects on caregivers of cancer patients' needs and family hardiness. Psychooncology. 2016;25:84–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Vedsted P, Bro F, Guldin MB. Preloss grief in family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Psychooncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.4416. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldron EA, Janke EA, Bechtel CF, Ramirez M, Cohen A. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of life. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1200–1207. doi: 10.1002/pon.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterba KR, Zapka J, Cranos C, Laursen A, Day TA. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patient-caregiver dyads: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:238–250. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittenberg E, Kravits K, Goldsmith J, Ferrell B, Fujinami R. Validation of a model of family caregiver communication types and related caregiver outcomes. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15:3–11. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]