Background

Persons receiving a diagnosis of advanced life-limiting (stage III–IV) pancreatic cancer (PC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) abruptly need to face the potential for personal mortality.[1,2] While treatment options have improved, median survival is similar at 6–12 months for persons diagnosed with PC or NSCLC. These individuals experience worsened quality of life (QOL) and suffer from symptoms of anxiety and depression due to disease progression, hopelessness, and loss of dignity.[3–8]

Emotional and social problems can impact quality of life (QOL) as much as physical symptoms of cancer and its treatment.[9] Further, facing an advanced cancer diagnosis prompts many individuals to clarify their values and determine what is most important to them in life to elicit a sense of meaning and purpose.[1] Life review for those with advanced cancer, goes beyond simple reminiscence (pleasant remembering of past life events), to examine and review one’s life to obtain deeper meaning and ease death anxiety.[10]

Dignity Therapy (DT) is one form of life review. DT is a brief, empirically-based, psychotherapeutic intervention developed with the intent of enhancing a sense of dignity and improving QOL. [11,8,7,12] DT was derived from a model of dignity, which describes aspects of dignity experienced by those facing death, including illness-related concerns, dignity conserving repertoire and social dignity inventory. The intent of DT is to lessen distress, promote QOL, validate personhood, alleviate suffering, provide meaning for the participant, and provide a legacy document for the participant’s family and friends.[7] It was developed in response to an identified need in healthcare to promote ‘death with dignity’[11] and alleviate feelings of hopelessness and despair common at end of life.[13] The reflection by individuals during DT functions as a form of life review and values clarification. As part of the DT intervention, a Generativity Document is then written to serve as a formal record of both tasks. Briefly, DT typically consists of 2–3 sessions in which one is interviewed about his/her important life events and what types of messages they would like to impart to family or other loved ones. Initial interviews are audio recorded and transcribed, then edited by the interviewer to give the resulting Generativity Document clarity and appropriate ordering of events. During the second (and subsequent sessions as needed), the interviewer reads this document to the participant and the participant has the opportunity to further edit the document, adding or deleting interview content as desired. The final Generativity Document is given to the participant to share with family as desired. Previous DT intervention studies have primarily occurred at end of life.[14–17]

A few researchers have qualitatively described themes of DT interviews. A grounded theory approach was used to describe themes from an international sample of 50 patients receiving palliative care in the hospital setting; all but two had cancer. Themes were described as 24 core values, with the most common being family, pleasure, caring, and a sense of accomplishment.[18]Topics identified by 27 community-based hospice participants receiving DT were ranked by how often they appeared in Generativity Documents, such as “autobiographical information, love, lessons learned in life, accomplishments, character traits, unfinished business, hopes and dreams, catalysts, overcoming challenges, and guidance for others.”[19] When DT participants with advanced cancer were interviewed about the benefits of DT participation, themes of generativity, hopefulness, care tenor, reminiscence and pseudo life review were described.[20]

While what individuals report as important to them at end of life has been elucidated in previous DT research,[18–20]one challenge with providing DT at the end of life is that many individuals are unable to complete the intervention. [14,21,15–17] Given the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations to provide palliative care interventions simultaneously with treatment for advanced cancer, [22] we need to understand what individuals report as important to them when DT is offered earlier in the disease trajectory, as this may be expressed differently than at end of life. The purpose of this study was to identify what individuals with advanced PC or NSCLC describe during DT as important to them when they are facing the possibility of personal mortality but not immediate end of life.

Methods

Design

As a part of a larger mixed methods pilot study, [23] we used a qualitative descriptive approach. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Participants and setting

The setting for the study was the outpatient chemotherapy suite at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA. Interviews were conducted in private treatment rooms or in 6-recliner treatment rooms, with curtains drawn for privacy. Potential participants needed to be English-speaking adults age 18 or older, within 12 months of diagnosis and undergoing chemotherapy for advanced PC or stage IIIb/IV NSCLC, with a prognosis of 6 months or more. All needed to be cognitively intact, not currently receiving hospice or formal palliative care services, participating in other psychosocial intervention research studies, and without a psychiatric diagnosis.

Procedures

The principal investigator (AMD), an experienced qualitative researcher who has undergone formal DT training, conducted all interviews. The DT intervention was provided using a manual of procedures, with slight modifications to the original DT question protocol (Table 1).[24] Modifications to the questions were intended to lessen the original focus on end of life perspectives. Probing questions were added to verify timelines of biographical information and to provide clarity to the interviews.

Table 1.

Dignity Therapy questions

| 1. | Tell me a little about your life history, particularly the parts that you either remember most, or are the most important. |

| 2. | Are there things that you would want your family to always know about you? |

| 3. | What are the most important roles you have in your life (family, work, community service, etc.)? Why are they important to you? |

| 4. | What are your most important accomplishments, and what makes you feel most proud? |

| 5. | Are there things that you want to say to your loved ones, or things that you want to say again? |

| 6. | What are your hopes and dreams for your loved ones? |

| 7. | What have you learned about life that you would want to pass along to others? What advice or guidance would you wish to pass along to your child(ren), husband, wife, parents, other(s)? |

| 8. | As we create this document, are there other things that you would like to be included? |

| (adapted from Chochinov, 2005, 2012) |

Scheduled to coincide with participants’ cancer treatment appointments, DT consisted of three interviews, each 2–3 weeks apart. During the first DT session, participants completed the interview in which they related a brief life history and identified events and people important to them. Interviews were audio-recorded using digital recording devices and transcribed verbatim, using a secure, web-based transcription service. Transcripts were deidentified, paper copies kept in a locked cabinet and electronic files backed up on a private, secure server. This interview was then edited by the study team before DT session 2 and further edited with participants during DT sessions 2 and 3 to reflect the content they wished to include in a Generativity Document to give to their families later. During or immediately after the final DT session, participants received a paper copy of the edited Generativity Document and completed outcome measures. A member of the study team met with them to complete another set of outcomes measures after 3 months, signaling the end of the DT study. Study team members held regular meetings to support one another throughout the study and ensure adherence to methods.

Analysis

We chose to analyze only the original (first) interview transcripts and not the edited Generativity Documents in order to avoid potential bias from the editing process. Interviews continued until we reached data saturation. The unabridged, verified interview transcripts were qualitatively analyzed using content analysis techniques [25,26]. We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) standards for analysis and reporting of findings.[27] Each transcript was read through in its entirety first by members of the study team (AMD, LR), to capture the overall essence of each participant’s transcript. We used NVivo 11.0 software (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) for open coding, with a priori codes identified and additional codes added as they emerged. Independent coding was done initially between two coders (AMD, LR), with subsequent comparisons of coding, determination of coder agreement, and use of consensus in the case of discrepancies. Higher order coding and conceptual ordering occurred to organize codes into relevant themes. Regular meetings occurred among coders to record coding decisions to provide an audit trail for added rigor of findings. The interviewer maintained field notes to add richness and context to interviews.

Findings

Participants

We approached 45 patients for the study; 20 refused participation. Five withdrew before the initial interview, leaving 20 participants for the initial interview. They were primarily white, non-Hispanic or Latino, and “middle-aged” (Table 2). Two participants were not able to continue the DT intervention after the initial interview and later withdrew from the study. We included them in these results, though, as they completed the first two DT sessions. [23] Slightly more than half (55%) were female, with more females with pancreatic cancer than with lung cancer. Most were married and with greater than a high school education. The lung cancer participants were further out from their cancer diagnosis (mean of 22.8 weeks vs. 4.2 weeks for those with PC).

Table 2.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Group

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic Cancer (n=10) | Lung Cancer (n=10) | |

| Age, yearsa | 63.8 (10.95) | 62.7 (13.01) |

| Women | 9 (90) | 2 (20) |

| Race | ||

| White | 9 (90) | 10 (100) |

| American Indian | 1 (10) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (10) | |

| Other | 10 (100) | 9 (90) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 7 (70) | 8 (80) |

| Divorced | 2 (20) | 1 (10) |

| Widowed | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Education | ||

| HS graduation or less | 2 (20) | 3 (30) |

| College, 1–4 years | 6 (60) | 3 (30) |

| Graduate school | 2 (20) | 4 (40) |

| Time from diagnosis to DT enrollment in weeksa | 4.2 (2.3) | 22.8 (13.3) |

Abbreviations: DT, dignity therapy; HS, high school.

Values are mean (SD); all others are number of patients (%).

Qualitative Interview Themes

Family provided the overall context and background for participants’ stories. When participants spoke of family, most were referring to children and marriage, although when asked about family, many began with discussion of their growing up years with parents and siblings. For most participants, family was described as the most important component of life, thus providing the context for the other themes. Family was interwoven through all other themes we identified.

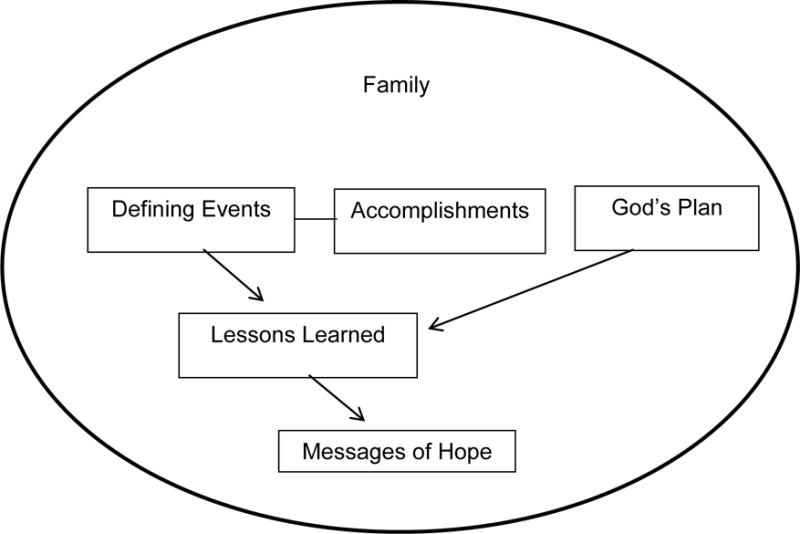

Themes identified in these twenty participants’ interviews included defining events, accomplishments, God’s plan, lessons learned, and messages of hope. Themes and their relationships are depicted in Figure 1. Defining events and accomplishments were often related. Defining events were often experiences or events that happened to participants such as experiencing hardship, illness of a family member, or abuse or neglect as a child and were often more external in nature. Accomplishments were described more often as things participants themselves did and were often described as things that they were proud of.

Fig. 1.

Qualitative interview themes

Belief in God’s plan emerged as a theme that was less related to defining events and accomplishments but did often relate to lessons learned in life. Lessons learned then became the theme most often derived from both defining events and God‘s plan. The final theme was messages of hope, or the legacy, advice, and hope participants wished to impart to family. Exemplars for each theme are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Exemplar quotes

| Defining | Childhood examples: |

| “…my stepdad was not a nice man. He was very abusive and everything… he would beat my mom a lot. He-he beat us kids…. he raped me countless times and… Well, it made it—made me who I am today, you know? (DT01) | |

| I remember growing up. We were very, very poor. But I can’t ever remember being hungry.… we …pretty much lived off the land. We had our own garden and grew most of the food we ate, canned it….We didn’t have electricity. We didn’t have running water. We didn’t have indoor plumbing. … if I could go back to those days, I would because they were good days. They were family oriented where you worked together. (DT11) | |

| “…we had to help mow, and we had to learn to do laundry, and we had to do dishes, and we had to, you know when we were young. And we had a paper route, and we—you know for things that we wanted we had to work for them, or we, we just learned to know that, that there’s a price to be paid basically for something….if you want something unlike what I think a lot of kids are taught these days. Um, so yeah we had paper routes, and then, you know, instead of doing the sports and stuff in high school we were working. Which, you know, like I said at the time it was so none of the other kids are doing it, but now I mean I wouldn’t have it … any other way.” (DT09) | |

| “…So I stayed with my grandmother, my mother’s mother and with my three younger brothers, one of them … my sister, and two boys, one of them the one that was ill. So that gave me the—I think very lucky for that opportunity because I got to be very close to my brothers, younger ones especially, and through this process of going through this special stage and special schools, I think it gave me a more, uh, sensible way of looking at life.” (DT14) | |

| Adult examples: | |

| “Just life itself, seeing a new life come into the world and then all of a sudden it’s scary because hey, you’re responsible for that child…my kids were the most important part of my whole life. Without my children, I don’t know what I’d do. (DT08) | |

| “Nothing humbles you like motherhood, right, so that was another defining moment in my life. Not moment, moments, years, but of course because you have these little rug rats I used to call them, but that was another defining time.” (DT06) | |

| …I came to the realization “I gotta make a change … was a day when I was at work on a weekend on my birthday and working, …And my wife and children all came to my workplace… uh, brought my party to me. … it made me realize I needed to do somethin’ different.” (DT20) | |

| “…about the time I learned I was pregnant with my first child. ….[my mother] ended up in the hospital and then, um, they were kind of going through this and they found something that needed be investigated. And then they found out that it was indeed something on her pancreas, um, and they were going to attempt to do the Whipple…but they opened her up and [crying] they closed her up. It had gone too far so the prognosis at that time was of course, six months…” (DT04) | |

| For a few, defining moments occurred related to their cancer diagnosis: | |

| “Well, sad thing is, is the first time I told my son that I—my oldest son—that I loved him was, um, Jesus, three months after I found out I had cancer. You know, when I said it, it about knocked him down, because we don’t talk to each other that way, you know, and I have done it with all the kids, and then I made it a point right after I got out of the first set of chemotherapy, is I took a month and left here, and I went and visited each one of my kids, and I stayed with them for two or three weeks, and I’ve never done that before, so they didn’t know what the hell to think of that, and especially my daughter, because I never did it with her. It’s a first time since she ever got married I have went and stayed in one of her houses, and I went and spent time with them.” (DT19) | |

|

| |

| Accomplishments | Children and role as parent examples: |

| “My family, my husband—ya know, I guess that’s the most thing I’m proud of. It’s the … thing that’s most important [crying]. …ya know that first of feeling of, “How could I love any more?” … It just grew and grew and grew abundantly…” (DT04) | |

| I think definitely the most important is mother and wife. I mean, I’ve been a teacher and of course that’s important. You can influence a lot of people. But when it comes down to it, your own—just being a mother has been my greatest, greatest, greatest accomplishment. So, very proud of that. (DT05) | |

| “Well, you know the thing about it is, anybody can be a father. You wanna be a daddy, it takes a hell of a lot of work, you know, and there’s a big difference in my world and a big difference in my life, you know, for being a father and being a daddy, and I pride myself on being a daddy.”(DT 19) | |

| “Three children, very successful at young age, if you talk to the people that have known them through their studies or working life, they admire them. Everybody says, “Well, to have a good kid is good luck. To have two good kids it’s a big, big luck. To have three kids like the ones you have is not luck. It’s hard work.” And my wife and I have done that very well. So I’m proud of that.”(DT14) | |

| Successful marriage examples: | |

| “We’ve been there for each other, and he had grown up in a very dysfunctional home, and so he really didn’t have anybody. I always knew he needed me…Yeah, a very good team because he’s strong where I’m weak, and I’m strong where he’s weak, and we just balance.”(DT03) | |

| “I’d say my third defining was in grad school. I met my husband. It was just defining because we’ve been good life partners all these years” (DT06) | |

| “I think another thing is being married 29 years. Anyone who’s been married learns that it’s not all like the first year. [Chuckles] You make a lot of compromises, and there’s a lot of things you go through, and I think it’s not easy. … I’m proud of the fact that we have been married that long cuz I know lots of wonderful people it doesn’t work out for, and that’s the way it is. …it’s been just a wonderful ride, and I wouldn’t do it any other way.” (DT20) | |

| Work examples: | |

| “I think, doing honest work and in a family business and helping employees develop themselves. That’s probably one of the greatest satisfactions that I have in my professional life, always helping how people grow in their job and reaching new heights.” (DT 14) | |

| “I guess accomplishment-wise, just the fact that in life, I’ve always, one way or another, found a way to take care of and provide for my family. I mean, yeah, there’s been some - some bumpiness and rockiness … but we made it through it, you know.” (DT 18) | |

| “That’s like we tried to do a good job of farmin’, ya know. The neighbors looked at it. You didn’t hear ‘em complainin’ about my weed field. I fed a lot of cattle.” (DT 12) | |

|

| |

| God’s Plan | “… no matter what, God is in control of everything. That even through these difficult times, I think that God is definitely in control… there’s a bigger picture. (DT04) |

| “…you know, we’ve had about a five and a half, almost six-month stretch here of a pretty extreme low, but it’s part of God’s plan is how I look at it. …even though she’s been more upset than me about it, my wife gets that too. … It’s part of his plan. There’s a reason. We might not totally get it yet. We may never get it, but there’s a reason. Um, so I think we just take it a day at a time and see where it takes us. (DT18) | |

| “I’m not a church-going person by no means. I have my beliefs, and I don’t believe like … a lot of people… I believe he’s up there. I believe in a higher power, always have been. …this is just a journey (DT19) | |

|

| |

| Lessons Learned | “Control the things you can control. Don’t dwell on the things you can’t. Treat people with kindness and trust until they show you that they don’t deserve your trust. … You don’t have to trust everybody … but go into interactions with people that way. Assume the best and see what happens. Make sure you make good friends and have them around you as well because it means a lot.” (DT20) |

| “First of all, never get attached to material things in life no matter how wealthy you become. Wealthy just… a result of hard work but it has to be just to support in life so you don’t need anything important, but not to make it an object in life. And the second thing is to do for others. For me it’s very important through life and I’ve taught that together with my wife to our children. Always be thinking what you can do for others. “ (DT14) | |

| “Stop and smell the roses. It’s not a joke, you know. It’s a saying for a reason. enjoy life day by day, not worry so much. It’s good to have long-term goals, you know. I think people should have one-year goals, five-year goals, ten-year goals, whatever. Don’t focus so much on that ten-year goal that you’re missing everything between now and then cuz it goes by fast, and odds are good that your ten-year goal isn’t anywhere near where you set it to begin with.” (DT18) | |

| “Appreciate what you have right now.” (DT22) | |

| Lessons learned specifically with dealing with a cancer diagnosis: | |

| “I .. always know that they’re gonna be okay cuz no matter what, they’re okay. … they came in the room and I said, “We’ve been preparing for this moment all our life. We’ve got what it takes. We’ve got all the tools. We’ve got everything.” (DT04) | |

| “…everybody should appreciate every day they have, ‘cuz you just don’t know… I’m not even specifically referring to the cancer issue. I mean, it can be… you get killed crossing the street or something. …really just enjoy every day that you have. …Let your friends and your family know that you love them. And just appreciate, appreciate every day. And don’t worry about the little things.” (DT05) | |

| “…I just wanna be home… I wanna be close to my loved ones. And I’m so lucky that I have a home …I’m just happy there. I don’t need any big trips. I don’t need any big events. … no big changes in the foreseeable future… Everybody dies of something. If you have to die of something, there’s never enough time to do everything you want to do, so you better pick whatever you enjoy. Don’t waste any of it doing things that you don’t enjoy.” (DT09) | |

| “Life’s what you make of it…when I first found out about this …you have two paths you can go down. You can either go down the “poor me” path and feel sorry for yourself and wither away and die, or you can fight. I chose to fight. I’m not done fighting.” (DT19) | |

|

| |

| Messages of Hope | “I hope they keep the family close…I don’t hope that they all become wealthy. Sometimes, that’s not a good thing. I hope they understand the things you work for are the things that are gonna be the most important to you. Just keep your family together, take good care of your kids, and teach them all the right things. Set the examples.” (DT 11) |

| “My hopes and dreams for them is that they’re happy, you know? Because… people don’t realize you could be a janitor and be happy, you know? …it’s not about how much money you make. It’s not about the job you have or anything. It just, … to be happy where you’re at, to be content.” (DT01) | |

| “I would hope that they could find… someone to love and to love them the way that… they need to be and should be loved….not to ever settle for anything less than that” (DT04) | |

| “I hope my husband can find love again after me, if he wants… I hope that I’ve been around him long enough to teach him that there’s a funnier side to life. Everything doesn’t have to be so serious, and maybe … he should just do what makes him happy.” (DT09) | |

| “we may not always understand why we go through these difficult times, but I just hope that they understand that life isn’t always gonna to be a bed of roses. I mean, we’ve learnt that first hand… It’s been a big bed of roses, and now we’ve run into some thorny areas.” (DT05) | |

| “Number one, take every day and not doomsday like it’s your last, but make the best you can of each day in your life. And you’re gonna mess up, but then go to the next day and try not to make the same mistakes again…I could tell my daughter especially, a lot of things. ‘Cause I’m seeing her do some of the same dumb things I did.” (DT10) | |

| “I’ve taught them to be tough and continue life happily, not sad. If …I’m absent they should continue a good life doing good for others and working hard and not make any changes. If tough things come, just accept them. Don’t change life. Don’t change ideas. Don’t change religion…just keep being the same good person as before. ” (DT 14) | |

| Hopes for the use of the Generativity Document: | |

| “Yeah. I just really wanted to have something that they would have….I’m hoping that … 20 years from now, they’ll look at this or will share this together and say, “Yeah, let’s look at that. See what’s changed or what I hafta’ add to it.” That’s my dream. That’s my hope. That’s my wish—and I never stop hoping. …I do want them someday to have something that they actually can have in their hands that they know was from me.” (DT04) | |

Defining events

Defining events were those life events that had a major impact on individuals’ lives. For some, this was a moment; for others it was more part of how they grew up or how life events in general shaped them. Participants talked about how their growing up years, especially their experiences as children, served as context and background for who they were today. For others, defining events were those from adult years, again with the effect of making them rethink what their lives had been until that point and these either modified their life direction or validated what they already knew. There were very few examples of defining moments that emphasized their cancer diagnoses.

Accomplishments

Accomplishments were achievements participants took pride in and that brought meaning and purpose to their lives, such as raising successful children, having a successful marriage, or work successes. These were mostly things they had done, rather than ways of being or things that happened to them. Raising successful children was defined in different ways: success in school, children being good people, or now being settled in their adult lives. Study participants viewed their role as parent as one of their biggest accomplishments. The achievement of a successful marriage was often described beginning with autobiographical information about their relationship. They spoke of the balance between strengths and weaknesses for the couple, the synergy and support between them, and the significance of the relationship to them over the years. While many spoke of successful marriages, not all participants experienced this and related very different experiences. Participants spoke of work accomplishments as part of caring for their families, but also that work was not just about bringing home a paycheck, but about doing satisfying and meaningful work. Participants enjoyed helping other people grow, working hard and trying to do a good job. For most participants, accomplishments represented longer-term experiences, not single events or moments.

God’s plan

Most individuals spoke of spiritual matters not as spirituality or religion, but as a relationship with God. In particular, participants described their belief that God has a plan. It is particularly noteworthy that none of the interview questions directly related to spirituality or religion. “God’s plan” was the language of participants. This seemed to lessen their distress and gave peace to many participants. They acknowledged that what had happened to them throughout life was bigger than what they were and provided a framework for appraisal of their present situation. Many who raised this topic spoke of comfort in accepting that what they were experiencing was part of a larger picture and that as a result things would be ok for themselves and their families. Belief that God has a plan conveyed a sense of purpose in life events, that everything that happened to them was a part of the journey, and that God was in control.

Lessons Learned

Participants also shared multiple lessons learned throughout life, which were often described as their mottos for living. These lessons were often depicted as the values by which participants wanted others to be aware of and to share. In some cases, lessons learned were the result of one or more defining events, but not always. These lessons made an impact on individuals’ lives, containing wisdom they often wanted to share with others. Some spoke directly of lessons learned specifically with dealing with their cancer diagnosis.

Messages of hope

Participants often took what lessons they had learned throughout life and then voiced their messages, hopes, and wishes, which were mostly directed to family. Most framed messages as advice, guidance, and love for family, especially children and usually adult children. Hope that the family member was already aware of the participant’s love was a central theme. Many began their messages with “they already know this…”, so messages were intended as validation of prior conversations. If advice was given, it was not to achieve wealth or success; it was to be good human beings. Participants also expressed hopes and dreams for future relationships, education and life events for their children and spouses.

Others spoke of difficult times and offered advice/comfort to get through them, as well as hope that their own family members would not have to go through cancer diagnosis/treatment. Some voiced regret and sadness for the past, as well as for the future. Some also took this opportunity to say they were sorry. In addition, many messages were faith or spirituality-based. Finally, some also spoke of hopes for the use of the Generativity Document.

Discussion

The overall context and perspective for these interview themes was family, which was the most important aspect of life to these individuals. Family was the viewpoint from which everything else emanated: defining moments, accomplishments, God’s plan, lessons learned, and messages to family. That the thematic figure emerged the way it did, with messages for family as the final product is in keeping with the intent of DT - to produce a Generativity Document to leave behind for loved ones. Through the brief autobiographical nature of the DT interview, participants were able to reflect upon what was most important to them and described what contributed to their legacy.

Many of the interviews also contained much reminiscence content (remembering of past events) and were autobiographical in some ways, which is similar to findings by others. [20,19] This was largely influenced by the questions guiding the interview (Table 1). The nature of the interviews was consistent with the purpose of DT, mainly for life review [7], particularly with the first interview question. The intent of these interviews was to produce the Generativity Document– a legacy document participants would leave for their families, so the nature of the interview questions needs to be acknowledged as influencing these findings. Participants, though, verified that the final Generativity Document reflected their personalities and individuality.

Despite the fact that these patients were cancer patients diagnosed within the past year, relatively few participants spoke about their cancer diagnosis during the interview. Healthcare practitioners might anticipate this to be a defining event, but for these participants little discussion of the cancer diagnosis was present in the interviews suggesting that their diagnosis, at least in terms of what they wanted their families to know, was not the most significant milestone. This finding is similar to those by others when DT was done closer to the end of life.[18,19] We surmise that this interview, in alignment with principles of DT, was an opportunity to talk about life, not illness. We also noted that many of these individuals had already had many defining events prior to their cancer diagnoses, such as childhood abuse, poverty, or marital abuse. Despite these challenges, no participant needed further support of counselling during or after interviews. All related these life events calmly and objectively as a part of their life reviews. We also surmise that those who declined study participation, either during recruitment or later may have anticipated that DT might be emotionally challenging. Particularly, two lung cancer participants explicitly stated that they believed the conversation would be too hard on them or they didn’t like to “talk about that stuff.” Some participants alluded to DT as a helpful distractor while they were receiving their chemotherapy, as it helped “pass the time.” Perhaps DT helped them remember who they were before cancer diagnosis.

Lessons learned was also predominantly shaped from the standpoint of family and relationships and more often than not emanated from defining events. This theme contained a flavor of advice from participants. Others have described that part of lessons learned during DT interviews is accepting and acknowledging one’s imperfection or celebrating what one has.[19] This is consistent with our findings in which lessons learned often stemmed from defining events and recognition of accomplishments.

Findings in this study are consistent with others (Hack, 2010) in which accomplishments were viewed as lasting contributions, achievements, or occupational attainment. Pride in one’s children was also included in the category of accomplishments, similar to findings by Montross et al. [19] Participants also defined accomplishments more in the realm of family roles as parent or spouse than in professional accomplishments. This aligns with previous work in which those who place higher importance on material goals in life report a lower purpose in life [1], but we also acknowledge that the majority of our respondents were married which may influence the value placed on family roles.

Participants in this study readily identified messages they wanted to leave for their family, similar to messages of hopes and dreams found in other DT studies, including how much they loved their families and had hopes for their happiness.[19,18,20] There were fewer conversations, though, about regret, which differs from work with a hospice population [19]. In addition, these messages of hope from individuals not at the end of their lives were less directive than if given at end of life. There was perhaps less urgency in participants’ messages than if DT was done in the palliative or hospice care setting.

This study adds unique insight into the use of DT in a population in which active cancer treatment was still the focus, different from work by others in which DT was offered within the last 6 months of life.[7,14,19,17,15] Challenges with delivery of DT in complex situations have been acknowledged, and include those in which participants can be undergoing rapid health decline, increasing physical symptoms, and increased emotional distress.[14] In our study, challenges included logistics surrounding the complex treatment regimens patients were navigating. We remained flexible with how we provided DT, for example, delivering the intervention after participants had their chemotherapy infusions started, but before drowsiness occurred after antiemetic medications were administered. We found it was feasible to provide DT for those still undergoing active treatment for cancer.[23]

We also did not know how much prognostic information patients had already been given or what their personal beliefs were about long-term survival. Some did talk about their cancer diagnosis, but there was no stated anxiety or depression; many spoke in terms of hope and an acceptance of God’s plan for them. This is in accord with a spiritual legacy intervention with some similarities to DT, in which relationship with God or the spiritual was a predominant theme.[28]

While this study adds new knowledge about DT in patients undergoing active cancer treatment, our findings must be interpreted in light of study limitations. All participants were recruited from a single large, tertiary care referral center. There was little racial or ethnic diversity in this sample, but it does reflect the demographics of the local and regional Midwest United States patient population. We cannot explain the gender “clumping”, e.g., the pancreatic participants being primarily female and the NSCLC participants being mostly male, but we achieved gender balance between the two groups. There were a number of individuals who refused study participation, but this is consistent with other DT studies [14,16,15] and study participation with palliative care research as a whole. [29]

Conclusions

This research adds to the current life review and psychosocial intervention research by elucidating what individuals facing life-limiting illness identify as important to them while undergoing active treatment for their advanced cancers. Family is of the utmost importance, but reflecting on who they are and have been as individuals demonstrates a sense of pride in what they have accomplished, clear identification of defining moments throughout life, and an acceptance of God’s plan for them. They were clear in sharing what they learned throughout life, but wanted to impart messages of hope to those closest to them. As oncology practitioners, we have much to glean from the lessons they have learned and the messages of hope they impart.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Catherine Krecke for coordination of this study. Grants: This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by the Saint Marys Hospital Sponsorship Board. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH or Saint Marys Hospital.

Footnotes

ORCID #0000-0003-4142-8655

Conflict of Interest

We do not have a financial relationship with the organization that sponsored this research. We have full control of all primary data and we agree to allow the journal to review data if requested.

Contributor Information

Ann Marie Dose, Nurse Scientist, Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905.

Lori M. Rhudy, Nurse Scientist, Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905.

References

- 1.Pinquart M, Silbereisen RK, Frohlich C. Life goals and purpose in life in cancer patients. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2009;17(3):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hullmann SE, Robb SL, Rand KL. Life goals in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psycho-oncology. 2016;25(4):387–399. doi: 10.1002/pon.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oechsle K, Wais MC, Vehling S, Bokemeyer C, Mehnert A. Relationship between symptom burden, distress, and sense of dignity in terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2014;48(3):313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun V, Ferrell B, Juarez G, Wagman LD, Yen Y, Chung V. Symptom concerns and quality of life in hepatobiliary cancers. Oncology nursing forum. 2008;35(3):E45–52. doi: 10.1188/08.onf.e45-e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark KL, Loscalzo M, Trask PC, Zabora J, Philip EJ. Psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer–an understudied group. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(12):1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/pon.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-oncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(24):5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2026–2030. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)12022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagland R, Richardson A, Ewings S, Armes J, Lennan E, Hankins M, Griffiths P. Prevalence of cancer chemotherapy-related problems, their relation to health-related quality of life and associated supportive care: a cross-sectional survey. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24:4901–4911. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keall RM, Clayton JM, Butow PN. Therapeutic Life Review in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Evaluations. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2015;49(4):747–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care–a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. Jama. 2002;287(17):2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM, Hack T, McClement S, Kristjanson L, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a developing empirical model. Social science & medicine (1982) 2002;54(3):433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClain-Jacobson C, Rosenfeld B, Kosinski A, Pessin H, Cimino JE, Breitbart W. Belief in an afterlife, spiritual well-being and end-of-life despair in patients with advanced cancer. General hospital psychiatry. 2004;26(6):484–486. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, Harlos M. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(8):753–762. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70153-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juliao M, Oliveira F, Nunes B, Vaz Carneiro A, Barbosa A. Efficacy of dignity therapy on depression and anxiety in Portuguese terminally ill patients: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Journal of palliative medicine. 2014;17(6):688–695. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vergo MT, Nimeiri H, Mulcahy M, Benson A, Emmanuel L. A feasibility study of dignity therapy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer actively receiving second-line chemotherapy. The Journal of community and supportive oncology. 2014;12(12):446–453. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vuksanovic D, Green HJ, Dyck M, Morrissey SA. Dignity Therapy and Life Review for Palliative Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2017;53(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hack TF, McClement SE, Chochinov HM, Cann BJ, Hassard TH, Kristjanson LJ, Harlos M. Learning from dying patients during their final days: life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliative medicine. 2010;24(7):715–723. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montross L, Winters KD, Irwin SA. Dignity therapy implementation in a community-based hospice setting. Journal of palliative medicine. 2011;14(6):729–734. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall S, Goddard C, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. “It makes you feel that somebody is out there caring”: a qualitative study of intervention and control participants’ perceptions of the benefits of taking part in an evaluation of dignity therapy for people with advanced cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2013;45(4):712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houmann LJ, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. A prospective evaluation of Dignity Therapy in advanced cancer patients admitted to palliative care. Palliative medicine. 2014;28(5):448–458. doi: 10.1177/0269216313514883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Ferrell BR, Loscalzo M, Meier DE, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Somerfield M, Stovall E, Von Roenn JH. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dose AM, Hubbard JM, Mansfield AS, McCabe PJ, Krecke CA, Sloan JA. Feasibility and Acceptability of Dignity Therapy/Life Plan for Patients With Advanced Cancer. Oncology nursing forum. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.E194-E202. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chochinov HM. Dignity therapy: final words for final days. Oxford University Press; Oxford; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giannantonio C. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd. 2. Vol. 13. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. pp. 392–394. (Organizational Research Methods). Book Review: Krippendorff, K. (2004) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care: journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piderman KM, Egginton JS, Ingram C, Dose AM, Yoder TJ, Lovejoy LA, Swanson SW, Hogg JT, Lapid MI, Jatoi A, Remtema MS, Tata BS, Radecki-Breitkopf C. I’m Still Me: Inspiration and Instruction from Individuals with Brain Cancer. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. 2016 doi: 10.1080/08854726.2016.1196975. doi: http://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/08854726.2016.1196975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]