Abstract

We evaluate the anti-cancer capacity of plasma-treated PBS (pPBS), by measuring the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS, treated with a plasma jet, for different values of gas flow rate, gap and plasma treatment time, as well as the effect of pPBS on cancer cell cytotoxicity, for three different glioblastoma cancer cell lines, at exactly the same plasma treatment conditions. Our experiments reveal that pPBS is cytotoxic for all conditions investigated. A small variation in gap between plasma jet and liquid surface (10 mm vs 15 mm) significantly affects the chemical composition of pPBS and its anti-cancer capacity, attributed to the occurrence of discharges onto the liquid. By correlating the effect of gap, gas flow rate and plasma treatment time on the chemical composition and anti-cancer capacity of pPBS, we may conclude that H2O2 is a more important species for the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS than NO2 −. We also used a 0D model, developed for plasma-liquid interactions, to elucidate the most important mechanisms for the generation of H2O2 and NO2 −. Finally, we found that pPBS might be more suitable for practical applications in a clinical setting than (commonly used) plasma-activated media (PAM), because of its higher stability.

Introduction

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) is gaining increasing interest for cancer treatment, but the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood1–3. In general it is believed that the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) from the plasma are responsible for oxidative damage of biomolecules present inside the cells, eventually causing cell death4. These RONS are formed in significant amounts in CAPs operating directly in air, but even when the discharge gas is helium or argon, as is often the case in plasma jet devices, the plasma effluent comes in contact with the surrounding air when leaving the jet device, thus also forming RONS. Moreover, the discharge gas often contains some N2, O2 or H2O admixtures, thus the RONS can also directly be formed in the plasma.

The anti-cancer capacity of CAP has been reported already for many different cancer cell lines, including breast cancer5,6, lung cancer7–9, leukaemia10, pancreatic cancer11, liver cancer12–14, glioblastoma15–18, cervical cancer19, melanoma18–23, etc. Furthermore, CAP has been demonstrated to act selectively towards cancer cells, while leaving normal cells undamaged1–4. This selectivity has been attributed to the fact that cancer cells already have higher intracellular ROS concentrations than normal cells, and thus they have more difficulties to cope with extra oxidative damage caused by RONS from the plasma, while normal cells can defend themselves more easily, and thus reduce the oxidative stress and restore the balance24. In addition, other explanations have been put forward as well, such as a higher concentration of aquaporins in the plasma membrane of cancer cells, which can transport H2O2 from the plasma inside the cells25, and a lower concentration of cholesterol in the plasma membrane of cancer cells, which facilitates pore formation, and thus again enhances the transport of RONS from the plasma inside the cells26,27.

Direct CAP treatment of cancer cells or tissue also has some drawbacks, such as the need for a standardized plasma source and the way of delivery in the body, which can make it cumbersome for treatment of some organs. Therefore, plasma-activated cell media (PAM) or plasma-activated liquids (PAL) have gained increasing interest for cancer treatment18,28–37. Until now, the focus was mainly on the use of cell media for the plasma treatment of cancer cells. For instance, Sato et al. showed that PAM leads to killing of HeLa cells28 and Tanaka et al. observed that PAM selectively kills glioblastoma brain tumor cells and induces morphological changes consistent with apoptosis15. Vermeylen et al. compared CAP and PAM treatment for two melanoma and two glioblastoma cancer cell lines, in different plasma gas mixtures18. Recently, Canal et al. showed that the effect of direct treatment of cells is comparable to that of the indirect treatment of cell medium that is subsequently added to the cells29. Some efforts are also undertaken to exactly control the anti-cancer activity of PAM. Yan et al. pointed out that the killing capability of PAM can be controlled by regulating the concentration of fetal bovine serum (FBS) in media30. Furthermore, they showed that the addition of selected amino acids to the media can either enhance or reduce the anti-cancer effect of PAM31,32. Adachi et al. demonstrated that PAM stored at – 80 °C can remain stable for at least a week33. In general, PAM seems to have similar anti-cancer effects as direct CAP treatment, but it can be more generally applied, by directly injecting it into the tissue of patients.

Furthermore, instead of PAM, it could also be interesting to treat solutions with a more simple composition with plasma, and to apply these plasma-treated solutions to cancer cells. Certainly in a clinical setting, they can be seen as more standardized solutions, and they are also more suitable for the investigation of the species and mechanisms playing an important role in the anti-cancer activity of PAL, because they are not cell line dependent. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) is an example of a simple buffered solution. Yan et al.34 showed that plasma-treated PBS (pPBS) is more stable than PAM, which is an advantage for the storage of this PAL. Only recently researchers started to use PBS for plasma treatment of cancer cells17,32,35–38. Wende et al.35 studied the differences between two plasma jets and the influence of ROS scavengers on the cell cytotoxicity, as well as on the concentration of H2O2. Boehm et al.36 investigated the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of different solutions exposed to plasma, such as cell media, FBS and PBS. Yan et al.32 reported that the degradation of PAM, which they consider as the main disadvantage of PAM, can be stabilized by using pPBS. In a subsequent study, Yan et al.37 compared the anti-cancer capacity of PAM and pPBS and concluded that the vulnerability of cancer cells to PAM/pPBS is cell-dependent. Girard et al.38 studied the effect of pPBS on the viability of normal and cancer cells. Finally, Tanaka et al.39 recently used Ringer’s lactate solution as another simple solution for PAL, which was effective in killing glioblastoma cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo, due to the formation of secondary species formed via interaction of lactate with plasma RONS.

The advantages of using PAM and pPBS, or PAL in general, are rather clear, however, their anti-cancer potential is still only scarcely explored, mainly because the underlying mechanisms are largely unknown. The liquid phase chemistry of solutions exposed to plasma is quite complicated. Recently, a very comprehensive review paper was published on plasma-liquid interactions, stating the upcoming challenges, as well as the fact that there are many unresolved questions in plasma-liquid interaction40. Measuring the RONS concentrations in PAM and PAL is gaining increasing interest in recent years40–44, because they play key roles in the mechanisms taking place at cellular levels. Knowing which species are present can provide information to reveal the mechanisms taking place in the plasma treatment of cancer cells. Several RONS are suggested to play a role in the anti-cancer effect of CAP, such as OH, O2 −, O, NO, H2O2, NO2 −, NO3 −, ONOO, NO2 and ONOO−4. However, when using PAL or PAM, only the long-lived species are of interest. H2O2 31–33,45–48 and NO2 − 38,49 have been regarded as the key species in the anti-cancer activity of PAM. In the context of pPBS, only few studies on the effect of RONS on the cancer cells have been published. Girard et al.38 measured the concentrations of H2O2, NO2 − and NO3 − in pPBS and found that H2O2 and NO2 − have a synergistic effect on the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS, while NO3 − does not contribute to the killing of cancer cells. They also investigated the effects of treatment time and gas flow rate on these concentrations, but they only considered one or two different operating conditions for plasma treatment. Yan et al.37 showed that NO2 − alone has no killing capacity for cancer cells, while H2O2 does.

In the present paper, we focus on the effect of the long-lived species NO2 − and H2O2, produced in plasma-treated PBS (pPBS). In addition to the experiments, we also perform chemical kinetics simulations to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of NO2 − and H2O2 production and loss. We use an argon plasma jet kINPen® in this study (see Materials and Methods). It must be noted that different plasma sources have different characteristics, which may result in different nature and amount of plasma-induced RONS, and ultimately in different biological effects. As mentioned before, H2O2 and NO2 − are stated to play a key role in the anti-cancer effects of plasma treatment. Moreover, they can be easily identified, which is needed when considering many different conditions of plasma treatment. It is shown that different operating conditions (i.e. gap, treated volume, size of wells, etc.) have great influence on the concentrations of RONS and the anti-cancer capacity of PAM (e.g. ref.31) and therefore more efforts are needed to find the optimal operating conditions when treating liquids for plasma treatment. To identify the role of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS for plasma cancer treatment, we will measure their concentrations in pPBS, for several different operating conditions. Specifically, we will determine the effect of gas flow rate, gap, treatment time and occurrence of discharges on the liquid on these concentrations, and correlate the latter with the cell cytotoxicity effect of pPBS for exactly the same conditions. While the effects of (some of) these conditions have been investigated for PAM treatment in literature, to the best of our knowledge, they have never been studied for pPBS. The composition of PBS is quite different from that of PAM, and this may lead to specific trends in the effects of the operational conditions.

To correlate the chemical composition of pPBS with its anti-cancer capacity, we consider three different cell lines of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). GBM is the most common and lethal type of primary brain tumours50, classified as the highest rank for tumours of the central nervous system, as issued by the WHO51. These tumours are characterised by a high invasiveness, molecular heterogeneity and rapid spreading throughout the brain51. Furthermore, they exhibit a particular resistance to surgical and medical treatment and are extremely susceptible to relapse, leading to a poor median life-expectancy of 14.6 months and a 5-year survival rate of only 9.8% when treated with conventional therapy52. These numbers indicate that the treatment remains palliative in most cases, demonstrating the need for alternative approaches, such as plasma treatment.

Materials and Methods

Plasma jet device

For the plasma treatments, we use the kINPen® IND plasma jet (INP Greifswald/neoplas tools GmbH, Greifswald, Germany). It consists of a metal cap with a pin electrode (1 mm diameter) in the middle, that is separated by a dielectric capillary (internal diameter 1.6 mm) from a grounded ring electrode53,54. The plasma is created by applying a sinusoidal voltage (2–6 kVpp) to the central electrode, with a frequency between 1.0 and 1.1 MHz, and a maximum power of 3.5 W. To limit the temperature, the device operates in burst mode, i.e., the plasma is switched on and off with a frequency of 2.5 kHz and a duty cycle of 50%. The plasma is created inside the capillary, after which the reactive plasma species are carried with the gas flow towards the open side of the device, creating a plasma effluent with length of 9–12 mm and diameter of 1 mm53.

Cell culture

We evaluate the anti-cancer effect of pPBS for three human GBM cell lines (U87, U251 and LN229), which are grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco™ DMEM, Life Technologies, 10938025), to which we add 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco™ FBS, Life Technologies, 10270098), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco™, Life Technologies, 25030081), 100 units/mL penicilline and 100 µg/mL streptomycine (Gibco™, Life Technologies, 15140163). The cells are incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Plasma treatment of PBS

We apply the plasma jet to treat 2 mL PBS (pH 7.3) in a 12-well plate. We use argon gas (purity 99.999%) with a flow rate of 1–3 slm. We study the effect of three important plasma treatment parameters, i.e., gas flow rate, gap between device outlet and treated solution, and treatment time, as well as the effect of the occurrence of discharges at the liquid surface. The conditions used to link the chemical composition of pPBS with the cancer cell cytotoxicity (see below) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of conditions. Plasma treatment conditions applied for creating pPBS, for both the chemical analysis and the effect on the cancer cell cytotoxicity.

| Condition | Gas flow rate (slm) | Gap (mm) | Treatment time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 |

| 2 | 1 | 10 | 9 |

| 3 | 1 | 15 | 5 |

| 4 | 1 | 15 | 9 |

| 5 | 1 | 30 | 5 |

| 6 | 1 | 30 | 9 |

| 7 | 2 | 20 | 7 |

| 8 | 3 | 10 | 5 |

| 9 | 3 | 10 | 9 |

| 10 | 3 | 30 | 5 |

| 11 | 3 | 30 | 9 |

For conditions 1 and 2 the gap is small enough to have discharges at the liquid surface, more specifically, discharge streamers are visible between the head of the plasma jet and the liquid surface. In this case, the liquid surface acts as a third electrode, and the electrons start playing a role inside the liquid, by causing electron impact reactions. Note that when the gap is only 10 mm, but a higher flow rate of 3 slm is applied (conditions 8 and 9), no discharges take place, because the liquid is blown towards the sides of the well. For conditions 3 and 4 the gap is just large enough (i.e. 15 mm instead of 10 mm) to avoid the discharges.

Besides the conditions of Table 1, we also perform a more detailed study on the effect of plasma treatment time on the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS and on the cancer cell cytotoxicity. For this purpose, we apply a gas flow rate of 1 slm, 10 mm gap (i.e., condition 1 of Table 1), and plasma treatment times of 5 min, 2 min 30 sec, 1 min 15 sec, 37.5 sec and 18.75 sec. These treatment times are obtained by so-called “diluting” the treatment time consecutively by a factor of two.

Quantification of H2O2 in pPBS

For the detection of H2O2 we apply colourimetry, using the titanium sulphate method55. In acid environment, H2O2 reacts with Ti4+ ions, forming a yellow peroxytitanium(IV) complex (reaction R.1), which has an absorption maximum around 407 nm. This complex is stable for at least 6 hours56. After plasma treatment, NaN3 is added to this solution to avoid the destruction of H2O2 by NO2 − (reaction R.2)57. Indeed, NaN3 reacts with NO2 − according to reaction R.3, so that NO2 − disappears from the solution58. As these reactions occur in acidic environment, it is important to add the azide before the acid titanium(IV)-solution56.

| R1 |

| R2 |

| R3 |

The analysis is performed with a ThermoFischer GenesysTM 6 spectrophotometer. The cuvettes are made of quartz, and have a path length of 1 cm, a volume of 700 μL and an internal width of 2 mm. We measure the absorbance comparing with a blank solution at 400 nm. For this purpose, we prepare a solution of 80 mM NaN3 in PBS and a solution of 0.1 M K2TiO(C2O4)2.2H2O (Sigma Aldrich®, 14007) and 5 M H2SO4 in milli-Q water. For the measurements, we add 50 µL N3 –solution, 200 µL pPBS and 50 µL Ti(IV)-soluton to the cuvette. Concentrations are calculated based on the extinction coefficient determined in a calibration experiment (Supplementary Figure S1).

Quantification of NO2− in pPBS

For measuring the NO2 − concentration, we use the Griess method59 (Griess Reagent Nitrite Measurement kit, Cell Signaling Technology®, 13547).

The analysis occurs in a 96-well plate with a BIO-RAD iMarkTM Microplate reader. 100 µL Griess reagent (1:1 sulfanilamide and N-(1-naftyl)-ethylenediamine) and 100 µL pPBS are added to each well. Also a blank solution is made in the well plate. The absorbance is measured in triplicate. Concentrations are calculated based on the extinction coefficient determined in a calibration experiment (Supplementary Figure S2).

Measurement of O3 in pPBS

We also tried to detect O3 in the pPBS by means of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR). The analysis occurs in Ringcaps® 50 µL capillaries with a MiniScope MS 200 (Magnettech) spectrometer. The measurements are performed by adding 4-oxo-TEMP (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone) to pPBS. 4-oxo-TEMP was reported to react with ozone to produce a stable nitroxide radical 4-oxo-TEMPO (4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinyloxy).43 In our case, no radical formation is detected.

Treatment of cancer cells with pPBS

Before the treatment with pPBS, the U87 and LN229 cells are plated at 3000 cells per well, while the U251 cells are plated at 1500 cells per well in 150 µL medium in a 96-well plate. These seeding densities are based on our previous experience, as they appear to be suitable for our purposes. After incubation for 24 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the cells are treated with pPBS. For this purpose, we apply 30 µL of the pPBS to the 150 µL cells and medium present in the wells (which corresponds to a ratio of 1/6).

We also perform experiments in which catalase is added to the pPBS, as a scavenger for H2O2, in order to verify the role of H2O2 in the cancer cell cytotoxicity. For this purpose, 400 U mL−1 of catalase is added to the pPBS, after which the solution is stirred for 10–15 minutes. After this, 30 µL of pPBS + catalase is added to the cells in 150 µL medium. This experiment is carried out for conditions 1, 4, 6, 8, and 10.

Treatment of cancer cells with H2O2 and/or NO2− rich PBS

We also want to verify whether only the H2O2 or NO2 − in the pPBS is responsible for the anti-cancer capacity, or whether it is the cocktail of species that is important. For this purpose, we compare the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS with that of PBS to which H2O2 and/or NO2 − (as NaNO2) is added. Different solutions of PBS containing H2O2, NO2 −, or a mixture of both are prepared. The concentrations of H2O2 and NO2 − are the same as in the pPBS for the conditions considered, i.e. conditions 1, 4, 6, 8, and 10. To treat the cells, 30 µL of the H2O2 and/or NO2 − rich PBS solution is added to the cells in 150 µL medium.

Stability of pPBS

We also investigate the stability of pPBS by applying a gas flow rate of 1 slm, a gap of 15 mm and a treatment time of 5 min (i.e., condition 3 of Table 1). In a first set of experiments, we analyse the pPBS, and we add it to the cells, at fixed time steps after treatment, i.e., after 0 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 60 min and 120 min. In a second set of experiments, we assess the stability of cell medium to which we add pPBS (in a ratio of 1/6), by again analysing the chemical composition in this medium and by adding 180 μL of this medium to the cells (after removal of their original medium) at the same fixed time steps after treatment. For the chemical composition, we could only analyse the concentration of NO2 −, because in the case of H2O2, the air bubbles present in the cell medium after shaking the cuvette make it impossible to measure the solution in the spectrometer.

Cell cytotoxicity assay

After the treatment with pPBS, we analyse the cell cytotoxicity (meaning both cytostatic and cytocidal effects) by the sulforhodamine B-method (SRB)60. After removing the medium, the cells are fixed with 10% trichloro acetic acid (TCA). After washing away the TCA and the dead cells that are still present, we add 100 µL SRB (Sigma-Aldrich®, S1402) to each well. After thorough washing of the non-bound dye with 1% (vol/vol) acetic acid, and dissolving the bound dye with 100 µL tris-buffer (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, Sigma-Aldrich®, 252859), we measure the absorbance with the BIO-RAD iMark Microplate reader. The cell cytotoxicity is determined by comparing with an untreated control sample.

Description of the model

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for the production and loss of H2O2 and NO2 − in the pPBS, we also performed computer simulations with a 0D chemical kinetics model for the plasma jet in contact with liquid water. This model is based on solving balance equations for the different species, based on production and loss terms. In total, 91 different species and 1390 different chemical reactions are included in the gas phase (plasma jet in contact with ambient air) and 35 different species and 89 different chemical reactions are considered in the liquid phase. More details about the model, and the assumptions made to mimic the experimental conditions, are given in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information).

Results and Discussion

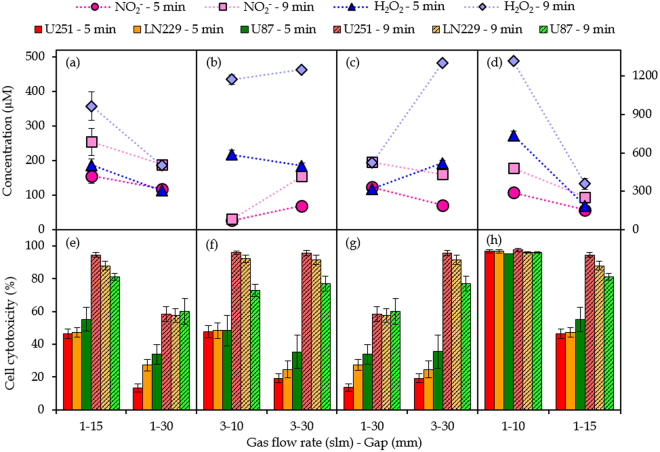

H2O2 and NO2− are present at different ratios in pPBS when applying different operational conditions, but in all cases H2O2 has a higher concentration

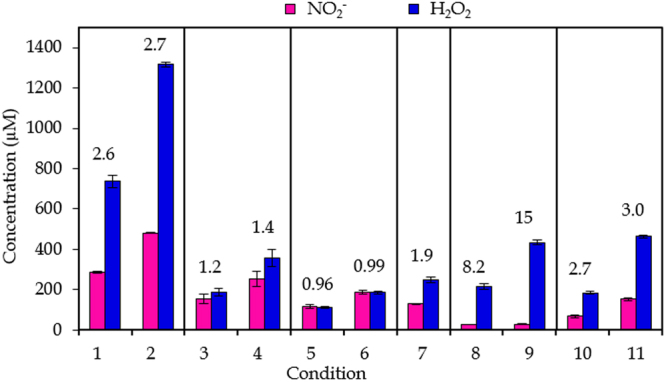

Figure 1 presents the measured concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 at the 11 conditions listed in Table 1 above. The ratios of the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 are also indicated in the figure. It is clear that the concentration of H2O2 is always larger than that of NO2 −. Comparing conditions where the gas flow rate and gap are kept constant but only the plasma treatment time is varied, tells us that the ratio of the concentrations is kept the same, except for conditions 8 and 9, where the concentration of NO2 − is extremely low. Thus, a high gas flow rate and small gap (conditions 8 and 9) favor the formation of H2O2 compared to NO2 −. Vice versa, at a low gas flow rate and a large gap (conditions 5 and 6), the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 are comparable, indicating that the formation of NO2 − is promoted.

Figure 1.

Results for chemical composition. Concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS at the 11 plasma treatment conditions listed in Table 1. Conditions for which only the plasma treatment time differs are indicated within one frame. The concentrations are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean. The numbers above the signals indicate the ratio of the concentration of H2O2 to the concentration of NO2 − for that condition.

The fact that different concentrations of species are formed by varying the plasma treatment conditions might be important in terms of the application, as some species will be more effective in killing the cancer cells, or might act even more selectively towards cancer cells than normal cells, in comparison to other species. Thus, by varying the plasma treatment parameters, the concentration of these particular species can be promoted.

Chemical kinetics modelling elucidates the most important source and loss processes for the generation of H2O2 and NO2−

Figure 2 presents the calculated liquid-phase concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 as obtained from the model described in the Supplementary Information, at the 11 conditions listed in Table 1. When comparing these results to the experimental data of Fig. 1, a reasonable agreement is observed. Indeed, although an exact quantitative agreement cannot be expected, due to the many assumptions made when using a chemical kinetics model, similar trends are observed in both the calculations and the experiments, in terms of (i) absolute values, (ii) higher H2O2 vs NO2 − concentrations at (nearly) all conditions, and (iii) variations in concentrations as a function of plasma treatment time, gas flow rate, gap, and the presence of discharges onto the liquid surface. This indicates that the chemical kinetics model provides a realistic picture of the gas-phase and liquid-phase chemistry over the entire range of conditions investigated, and can thus be used to elucidate the underlying mechanisms at these various conditions. A general scheme which includes the main pathways leading to the generation and loss of H2O2 and NO2 −, as predicted by the model, is depicted in Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

Overview of the computational results. Concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 at the 11 plasma treatment conditions listed in Table 1, as obtained from the chemical kinetics model (see SI). Conditions for which only the plasma treatment time differs are indicated within one frame.

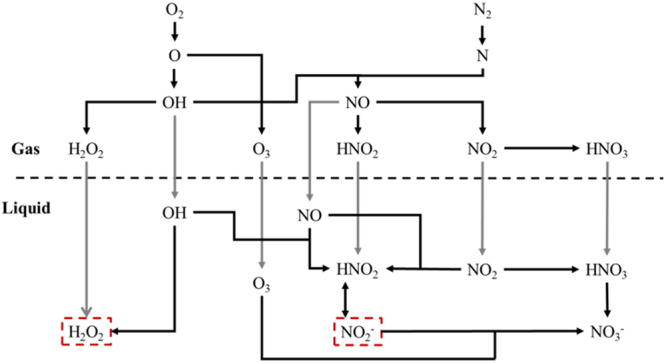

Figure 3.

Main pathways in both the gas and liquid chemistry leading to the generation of NO2 − and H2O2. The relative contributions of the different processes (i.e. chemical reactions (black lines) or diffusion processes (gray lines)) depend on the specific treatment conditions (see text). The gas-liquid interface is illustrated by the dashed horizontal line.

H2O2 in the liquid phase originates back from O atoms in the plasma effluent. These radicals are mostly generated by electron-impact dissociation (R.4) or by collisions of O2 with excited N2 molecules (R.5).

| R4 |

| R5 |

The O atoms react further with H2O molecules (present in the ambient air and as impurities in the feed gas), generating OH radicals (R.6).

| R6 |

Subsequently, two processes that lead to the generation of H2O2 in the liquid phase can occur, of which the relative contribution depends on the gap between the nozzle and the liquid. For larger gap, the OH radicals will have the time to recombine in the plasma effluent, generating H2O2 in the gas phase, which is subsequently transported into the liquid layer (R.7). For shorter gap, the gaseous OH radicals will be transport into the liquid themselves, where most of them recombine to aqueous H2O2 (R.8).

| R7 |

| R8 |

The calculated relative contributions of both pathways for the different conditions are listed in Table 2. Thus, if the time needed for the plasma effluent to reach the liquid is short (i.e. short gap and high flow rate), OH radicals that are transported into the liquid layer (where they recombine) are the main source for aqueous H2O2. For longer gap and lower flow rates, aqueous H2O2 mainly originates from gaseous H2O2, which is generated by OH radical recombination in the gas phase.

Table 2.

H2O2 generation. Contribution of H2O2 from the gas phase (R.7) and of OH radicals from the liquid phase (R.8), to the generation of aqueous H2O2.

| Condition | Contribution R.7 (%) | Contribution R.8 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 14 | 86 |

| 3–4 | 29 | 71 |

| 5–6 | 98 | 2 |

| 7 | 15 | 85 |

| 8–9 | 2 | 98 |

| 10–11 | 41 | 59 |

The different treatment conditions not only affect the contribution of different pathways leading to the generation of H2O2, but they also affect the absolute amount of H2O2 generated in the liquid, as is clear from Figs 1 and 2. Indeed, at high flow rates and short gap, a large fraction of gaseous OH radicals seem to survive transportation into the liquid. Thus, the aqueous OH concentration will be significant, which promotes the recombination of OH radicals into H2O2 in the liquid, as this reaction rate is linearly dependent on the OH concentration squared. On the other hand, at lower flow rates and longer gaps, many of the gaseous OH radicals will already recombine in the gas phase. This recombination will, however, occur mostly with N-species (such as NO or NO2), because their gas density is much higher than that of O-species (~80% of ambient air consists of N2). This has a double effect on the aqueous H2O2 concentration: (i) the gaseous density of H2O2 will not increase upon increasing gap, so its contribution to the aqueous H2O2 is very similar in all cases (at the same flow rate), but (ii) because the aqueous OH concentration is significantly lower at larger gap, the recombination rate into H2O2 in the liquid phase will be much lower. Consequently, the aqueous H2O2 concentration will decrease upon increasing gap.

For NO2 −, a similar analysis can be done. NO2 − in the liquid is in balance with HNO2 (see Fig. 3). The latter is mainly generated in the liquid by three processes:

| R9 |

| R10 |

| R11 |

The relative contribution again depends on the treatment conditions and is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

NO2 − generation. Contribution of different pathways to the generation of aqueous NO2 −.

| Condition | Contribution R.9 (%) | Contribution R.10 (%) | Contribution R.11 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 67 | 26 | 7 |

| 3–4 | 67 | 25 | 8 |

| 5–6 | 68 | 5 | 27 |

| 7 | 63 | 31 | 6 |

| 8–9 | 27 | 68 | 5 |

| 10–11 | 53 | 43 | 4 |

At 1 slm flow rate, ambient air species can easily diffuse into the plasma effluent, and thus the HNO2 concentration will already become very large in the gas phase, which explains why it is the most important source of aqueous HNO2. Upon increasing flow rate, it will become more difficult for ambient air species to diffuse into the plasma effluent. Moreover, the species that are initially generated in the gas phase (i.e. OH and NO) have less time to recombine before reaching the liquid phase. Hence, the relative contribution of R.9 decreases (most prominent when compared at 10 mm gap). By increasing the gap, the species have again more time to recombine in the gas phase, and thus the contribution of R.9 will increase again compared to R.10 (most prominent when compared at 3 slm).

In order to explain the absolute concentrations of NO2 − for the different conditions investigated, we have to keep in mind that to generate any of the HNO2 (and thus NO2 −) generating species (cf. R.9–11), both O2 and N2 are required. As mentioned before, by increasing the flow rate, the ability of these ambient air species to diffuse into the plasma effluent will drop. Therefore, the HNO2 concentration measured in the liquid is much more dependent on the gas flow rate than H2O2, as can be derived from Figs 1 and 2.

Moreover, Fig. 3 illustrates that the main loss process of NO2 − is the reaction with O3:

| R12 |

By increasing the gap, the amount of O2 that can diffuse into the plasma effluent will rise, and thus also the amount of O3 generated in the plasma effluent. This gaseous O3 is subsequently transported into the liquid, where it will react with NO2 −. This explains the drop in NO2 − concentration upon increasing gap (see Figs 1 and 2).

In summary, our model predicts that both H2O2 and NO2 − can be generated either (i) from diffusion of these species from the gas phase, or (ii) from aqueous reactions of short-lived species, and the relative contribution of both pathways strongly depends on the treatment conditions (flow rate and gap).

H2O2, rather than NO2−, is the more important species for cancer cell cytotoxicity

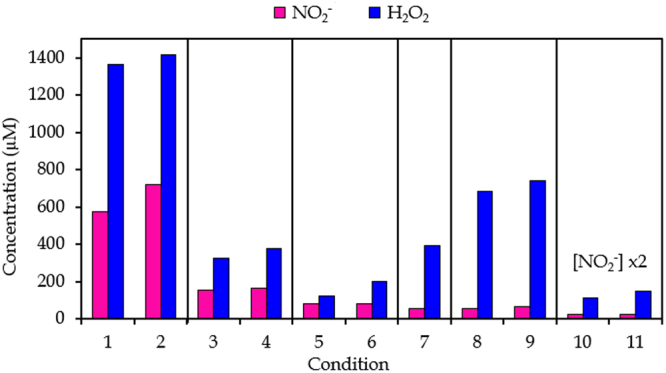

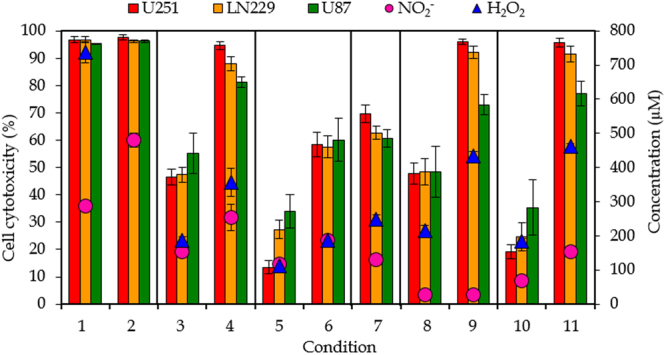

Figure 4 presents the percentages of cell cytotoxicity for the three cell lines, along with the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 shown in Fig. 1, at exactly the same conditions to make the correlation between both. To evaluate whether pPBS has the same effect on cell cytotoxicity for all three cell lines, we carried out a non-parametric t-test, which indicated that for the 99% confidentiality interval only condition 11 yielded a significant difference between the cell cytotoxicity for cell lines U251 an LN229 on one hand, and for U87 on the other hand. At all other conditions, the cell cytotoxicity could be considered similar for the three cell lines. There are some differences, but they can be attributed to different air humidity during the experiments, and to a different cell growth rate for the different cell lines. Indeed, when the cell lines exhibit different growth rates after treatment, this can yield a wrong picture about their sensitivity upon treatment with pPBS, as the cell survival was evaluated by the SRB method, where the total amount of proteins is a measure for the viability with respect to an untreated control sample. However, in this study we focus on the correlation between cell cytotoxicity and NO2 − and H2O2 concentrations in pPBS for different plasma treatment conditions. Therefore, we will not further elaborate on the different sensitivity for the different cell lines.

Figure 4.

General overview of the results. Effect of pPBS on cancer cell cytotoxicity for three different GBM cell lines (U251, LN229 and U87) (left y-axis), and comparison with the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS (right y-axis), for the 11 conditions listed in Table 1. Note that the H2O2 concentration in condition 2 is 1317 µM, but this is deliberately out of scale, to better evaluate the correlation between cell cytotoxicity and chemical composition for all other conditions. Conditions that only differ in plasma treatment time are indicated within one frame. The concentrations and percentages are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean.

In order to compare the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 with the percentage of cell cytotoxicity for all conditions investigated, it is important to note that the results of the latter are always limited to a maximum of 100% cell cytotoxicity, while the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 are not limited and can be higher than the concentrations needed to achieve 100% cell cytotoxicity. As a first tool for the determination of the most important species for the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS, we compare the trends between the cell cytotoxicity and the concentrations of the reactive species over all the operating conditions applied.

It is evident from Fig. 4 that the percentages of cell cytotoxicity exhibit the same trends as the concentrations of H2O2, but do not correlate with the concentrations of NO2 −. Indeed, when the concentration of H2O2 raises, a higher percentage of cell cytotoxicity is obtained, and vice-versa. On the other hand, at conditions 8 and 9, there is almost no NO2 − present in pPBS, while we observe a high percentage of cell cytotoxicity. Likewise, at conditions 3 and 11, the concentration of NO2 − in pPBS is very similar, while condition 11 causes twice as much cell cytotoxicity as condition 3. Thus, we may conclude from this overview that H2O2 most probably plays a more important role in cancer cell cytotoxicity than NO2 −, because the cell cytotoxicity follows the same trends as the H2O2 concentration over all the operating conditions. However, other species, like NO, NO3 − and ONOOH, can be important as well, either for killing the cancer cells, or for promoting the selectivity between cancer and normal cells (for which NO2 − may also play a role).

To further prove this statement, we perform experiments in which we add catalase to the pPBS after plasma treatment. Catalase is a scavenger for H2O2 and by adding it to the pPBS after plasma treatment, the H2O2 will be removed from the solution. For the conditions investigated (conditions 1, 4, 6, 8, and 10), adding the catalase results in no observed cell cytotoxicity in all cases (Supplementary Figure S5). This means that H2O2 indeed plays an important role for the anti-cancer activity of pPBS. From these experiments, one would expect H2O2 to be the only important species. However, further results demonstrate that this is not the case, and other plasma-induced RONS must be present in the system.

Sato et al.28 also showed that indeed H2O2 is most probably the dominant RONS inducing cancer cell death when using PAM.

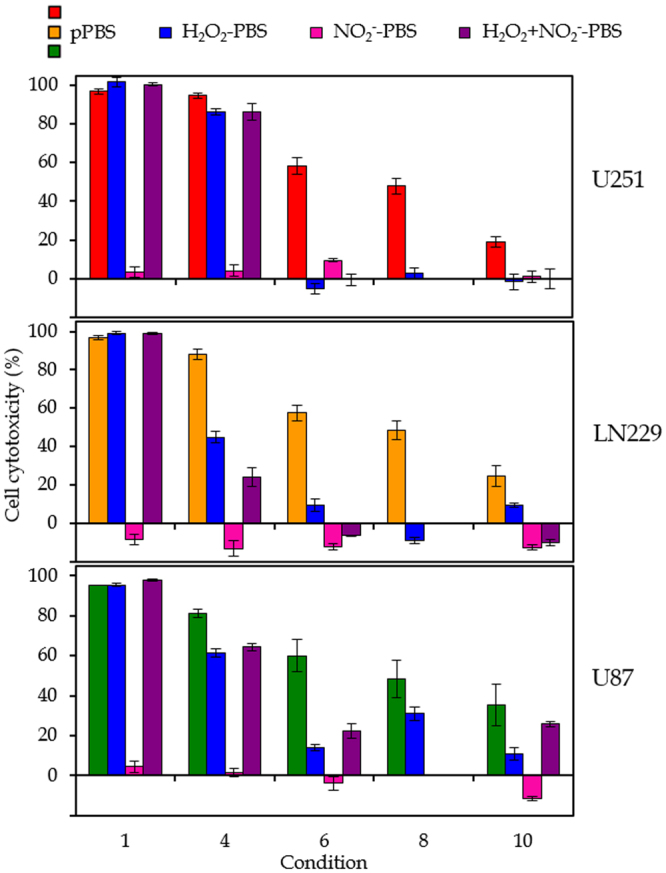

H2O2 and/or NO2− rich PBS has not the same effect on cancer cells as pPBS

Figure 5 presents the results of the experiments where we used H2O2 and/or NO2 − rich PBS to compare the effect on cell cytotoxicity with pPBS. The concentrations of the reactive species added to PBS match these in the pPBS for the conditions considered. Firstly, it is clear that NO2 − alone has no killing effect on GBM cancer cells in any case. On the other hand, the H2O2 rich PBS is able to kill the cancer cells in all conditions for the U87 cell line. For U251 cells, the H2O2 rich PBS has only a killing effect for conditions 1 and 4, and for the LN229 cells H2O2 significantly kills cancer cells in all conditions, except 8. This reveals that H2O2 indeed contributes to the cancer cell cytotoxicity in most cases, but it cannot be the only important species. When we consider both H2O2 and NO2 − in PBS, there is mostly no additional killing effect observed, except for the U87 cell line, where in all cases a synergistic effect of H2O2 and NO2 − is observed. We can conclude that the cell lines react differently on the addition of these reactive species, while the overall effect of pPBS on the three cell lines seems comparable (see above).

Figure 5.

Effect of H2O2 and/or NO2 − rich PBS on cell cytotoxicity. Comparison of the effect of pPBS with H2O2 and/or NO2 − rich PBS on the cell cytotoxicity for three different GBM cell lines (U251, LN229 an U87). The concentrations of H2O2 and/or NO2 − match these in the pPBS for the conditions considered (i.e. conditions 1, 4, 6, 8 and 10, which are listed in Table 1). For condition 8, no significant amount of NO2 − is measured in the pPBS. Hence, only H2O2 rich medium is tested for that condition. The percentages are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean.

This also suggests that catalase, as a scavenger of H2O2, does not only scavenge H2O2, but also other reactive species that appear to be important for the anti-cancer activity of pPBS. Indeed, catalase possibly scavenges peroxynitrite (ONOO−) too61, and possibly other RONS.

Girard et al.38 reported a synergistic effect of H2O2 and NO2 − when using pPBS on colon cancer and melanoma cells, which is in correlation with our results for the U87 cell line. Yan et al.31 demonstrated that adding only H2O2 to cancer cells does not have the same effect as PAM treatment, suggesting that other RONS also play a role. Kurake et al.49 reported that other RONS than H2O2 and NO2 − also participate in the anti-cancer capacity when using PAM, and found a synergistic effect of H2O2 and NO2 − on U251 cells. However, they used another plasma source that produces significantly higher relative amounts of NO2 − compared to the plasma jet used in our study. Indeed, while we always have higher amounts of H2O2 present in the pPBS, they measure NO2 − concentrations that are 30 times greater than that of H2O2.

Overall, it is unambiguous that H2O2 plays one of the major roles in the anti-cancer effect of pPBS, whereas NO2 − is less important. However, the cell cytotoxicity of pPBS cannot be explained by H2O2 rich PBS alone, and other reactive species must contribute to the cell cytotoxicity as well, when using pPBS.

Do the concentrations of H2O2 and NO2−, as well as the cell cytotoxicity increase linearly with plasma treatment time?

From Figs 1 and 4 we can easily deduce the effect of the plasma treatment time on the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in the liquid and on the cell cytotoxicity, because the conditions that only differ in treatment time are plotted within one frame. The ratios of the concentrations and cell cytotoxicity, for a plasma treatment time of 9 and 5 min, are listed in Table 4 for the different conditions investigated. For the results of chemical composition, it is clear that this ratio is close to 1.8 (i.e., the ratio of the treatment times) for most conditions, except for conditions 10 and 11 (for both NO2 − and H2O2) and for conditions 8 and 9 (only for NO2 −). However, for these last conditions, the concentrations of NO2 − are very low, making the results less reliable. It is yet unclear why the ratio at conditions 10 and 11 (i.e., high flow rate and large gap) is different from 1.8.

Table 4.

Effect of plasma treatment time. Ratios of the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS and of the cell cytotoxicity for the three cell lines, for the plasma treatment times of 9 and 5 minutes, for the different conditions listed in Table 1. A ratio of 1.8 suggests a linear increase of the concentrations with treatment time. Results that significantly deviate from the linear increase are indicated with an asteriks. The values are given as the ratios of mean values of at least three repetitions ± the standard deviation.

| Condition | Gas flow rate (slm) | Gap (mm) | NO2 − | H2O2 | U251 | LN229 | U87 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 1 | 10 | 1.67 ± 0.03 | 1.79 ± 0.08 | / | / | / |

| 3–4 | 1 | 15 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| 5–6 | 1 | 30 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.8* | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| 8–9 | 3 | 10 | 1.1 ± 0.1* | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| 10–11 | 3 | 30 | 2.3 ± 0.2* | 2.5 ± 0.1* | 5.0 ± 0.7* | 3.7 ± 0.8* | 2.2 ± 0.6* |

For the effect of the plasma treatment time on the cancer cell survival, we cannot use the results of conditions 1 and 2, because they both reach 100% cell cytotoxicity (cf. Figure 4). It is clear from Table 4 that the ratios of the percentage cell cytotoxicity are again close to 1.8, except for conditions 10 and 11 (which is in agreement with the chemical composition), and for U251 for conditions 5 and 6, which may be due to experimental variations.

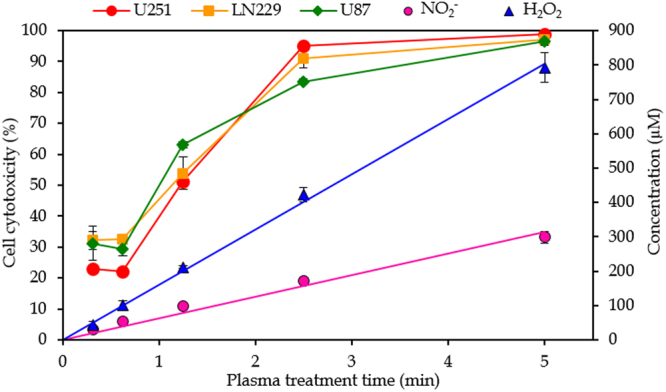

A more detailed study of the effect of plasma treatment time was performed as well, and the results are plotted in Fig. 6. The concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 indeed rise linearly with increasing plasma treatment time, until a time of about 5 minutes, at the conditions of gap and gas flow rate investigated here (i.e., 10 mm and 1 slm). We did not apply longer treatment times here, but Table 4 indeed suggests that this linearity more or less continues up to 9 minutes. Yan et al.31 also demonstrated a linear rise in the concentrations of RNS and H2O2 in PAM for a treatment time up to 2 minutes, when using a helium plasma jet. We may conclude from our results that up to 9 minutes of plasma treatment no saturation of the plasma species in the pPBS occurs.

Figure 6.

Effect of plasma treatment time. Concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS (right y-axis) and cell cytotoxicity (left y-axis) as a function of plasma treatment time, for a gap of 10 mm and a gas flow rate of 1 slm (i.e., condition 1 of Table 1). The concentrations and percentages are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean.

For the effect on the cell cytotoxicity, the shortest plasma treatment time (18.75 sec) apparently yields more or less the same cell cytotoxicity as the treatment time of 37.5 sec. Hence, it seems that small amounts of plasma species in the pPBS already give some cell cytotoxicity but that the effect is not linear here. On the other hand, a treatment time of 5 minutes results in 100% cell cytotoxicity at these conditions, so this data point cannot be considered for evaluating the linearity, as 100% cell cytotoxicity will be reached already somewhere between 2.5 and 5 min. It seems that the cell cytotoxicity does not increase linearly with treatment time for the U87 cell line, while the U251 and LN229 cell lines exhibit a more linear behaviour, although this is again based on only three data points. Several studies also reported a more or less linear effect of the plasma treatment time on cell death19 or RONS concentrations14,38,49 when using PAM, albeit also with some deviations.

Increasing the gap results in lower concentrations of NO2− and H2O2 and less cell cytotoxicity

The effect of the gap on the chemical composition of pPBS and the cell cytotoxicity is illustrated in Fig. 7(a,b,e,f). At a gas flow rate of 1 slm (Fig. 7(a)), both the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 show a drop upon increasing gap from 15 to 30 mm, although the drop is more pronounced for H2O2 than for NO2 −. Yan et al.31 and Takeda et al.62 also reported such a drop upon increasing gap when using PAM. This drop can be explained because the reactive plasma species are present in the gas phase for a longer time, so they have more chance to get lost upon reaction with other species. Hence, a lower amount of reactive plasma species (i.e. OH radicals for the H2O2 generation, and OH and NO radicals for the NO2 − generation, cf. modelling results above) arrive in the liquid, explaining the lower concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2. For NO2 − an additional explanation is provided by the modelling results above. A higher gap results in the formation of more O3, which will react with NO2 − in the liquid, lowering its concentration. On the other hand, at a gas flow rate of 3 slm (Fig. 7(b)), the NO2 − concentration rises upon increasing gap. It seems that this flow rate is high enough to transport the RONS into the liquid, without the risk for them to get lost by reactions. However, as the concentration of NO2 − at conditions 8 and 9 is extremely low, we cannot draw conclusions from this trend. For H2O2 the effect of the gap looks negligible at a gas flow rate of 3 slm. As mentioned above, we expect the concentration of H2O2 to be dependent on the reactions of OH radicals, either in the gas or in the liquid phase. At a gas flow rate of 3 slm, increasing the gap will have no significant effect on the H2O2 concentration, because the gas flow rate is high enough to enable the remaining OH radicals (not yet recombined to H2O2 in the gas phase) to reach the liquid, independent from the gap.

Figure 7.

Effect of plasma treatment parameters. Effect of the gap (a,b,e,f), gas flow rate (c,g) and discharges at the liquid surface (d,h) on the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS (a–d) and on the cell cytotoxicity for the three cell lines (e–f). For the effect of the discharges, the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 are plotted on the right y-axis. The concentrations and percentages are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean.

Figure 7(e,f) also demonstrates that a larger gap results in less cell cytotoxicity, both at 1 and 3 slm. Only for a treatment time of 9 min with a gas flow rate of 3 slm, the gap seems to have no effect. This might be correlated to the fact that the concentration of H2O2 at these conditions is also the same, thus pointing towards the important role of H2O2 in causing cell cytotoxicity. In general, the effect of the gap seems to be the same on the cell cytotoxicity and on the chemical composition, for both NO2 − and H2O2, but is more pronounced at lower flow rates than at higher flow rates.

The gas flow rate has an opposite effect on NO2− and H2O2, while the cell cytotoxicity acts similarly as H2O2

Figure 7(c,g) depicts the effect of the gas flow rate on the chemical composition, as well as on the cell cytotoxicity. A higher gas flow rate yields a slight drop in NO2 − concentration, but a rise in H2O2 concentration. Since the concentration of NO2 − depends on the surrounding air molecules (see above), we can state that a higher gas flow rate limits the number of air molecules that can come in contact with the plasma effluent, leading to a lower NO2 − concentration in the liquid. On the other hand, our modelling results reveal that the H2O2 formation depends on (i) the H2O2 from the gas phase reaching the liquid phase, and (ii) the recombination of two OH radicals in the liquid. As mentioned before, at high flow rates, the fraction of gaseous OH radicals that reach the liquid is large. Since the generation of H2O2 molecules is linearly dependent on the OH concentration squared, a significantly higher amount of H2O2 will be detected. It is clear that the H2O2 concentration is more affected by the gas flow rate than by the gap, while both effects are comparable for the NO2 − concentration.

A higher gas flow rate results in more cell cytotoxicity for all three cell lines. This correlates well with the trend of the H2O2 concentration, again suggesting that the cell cytotoxicity is primarily caused by H2O2 and less (or not) by NO2 −.

Girard et al.38 reported lower concentrations of both H2O2 and NO2 − when increasing the gas flow rate. However, they applied only two conditions to conclude this, and the gas flow rate was 8 times higher in the second condition. The fact that we consider lower variations in gas flow rate can explain these different findings, demonstrating again the importance of the operating conditions during the plasma treatment.

The occurrence of discharges on the liquid has a great effect on the concentrations of reactive species and on the cell cytotoxicity

Finally, the effect of discharges at the liquid surface is presented in Fig. 7(d,h). Enlarging the gap till a distance where no discharges take place anymore at the liquid surface (i.e., 15 mm instead of 10 mm) has a striking effect on the concentrations in the liquid phase. Note that the difference shown in this figure is the combination of two effects, i.e., a large gap and the disappearance of discharges. However, it was clear from Fig. 7(a,b,e,f) that enlarging the gap in the absence of discharges at the surface only has a minor effect. Therefore, we can conclude that the effect shown in Fig. 7(d,h) is predominantly due to the presence of surface discharges. The NO2 − concentration drops with a factor 2, while the H2O2 concentration even drops with a factor 4 upon disappearance of these discharges. For H2O2, the occurrence of discharges onto the liquid surface results in the formation of more OH radicals in the liquid (see Table 2), due to electron impact reactions with the water molecules in PBS. As predicted by our model, this results in higher H2O2 concentrations (see above). On the other hand, the relative contributions for the formation of NO2 − do not change with or without the presence of discharges (see Table 3). The electron impact reactions with the liquid have an overall rising effect on the reactive species present in both gas and liquid phase, resulting in higher NO2 − concentrations. As the raise of H2O2 is higher than that of NO2 −, we can conclude that the generation of H2O2 depends more on the generation of reactive species out of electron impact reactions.

As expected, the occurrence of discharges at the liquid surface results in more cell cytotoxicity. Indeed, a gap of 10 mm and flow rate of 1 slm results in 100% cell cytotoxicity, while the same flow rate but a gap of 15 mm results in ca. 50% and 90% cell cytotoxicity for a plasma treatment time of 5 and 9 min, respectively. This indicates that the occurrence of discharges at the liquid surface yields at least twice as much cell cytotoxicity, which is in agreement with the results for the chemical composition of pPBS.

PBS might be a better storage solution for RONS than cell media

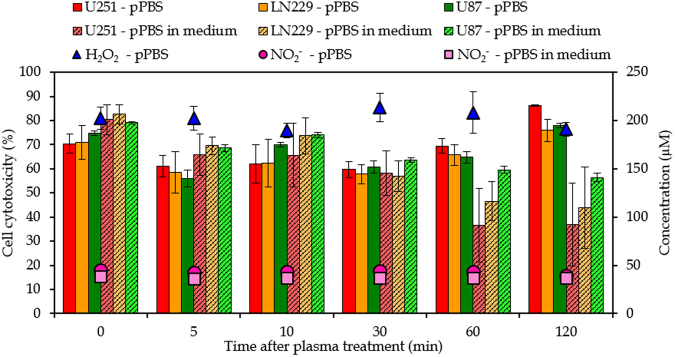

As mentioned in the Introduction, it is reported in literature that PAM can be stored during 7 days at a temperature of −80 °C33. Here we investigate the stability of pPBS at room temperature for a period of 2 hours. This would be convenient for practical applications of pPBS in a clinical setting. For this purpose, we measured the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS at fixed times after plasma treatment (see Fig. 8). The concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS obviously remain constant during at least 2 hours. We also added the pPBS to the cancer cells at these times after treatment and see that the effect on the cell cytotoxicity remains constant as well (see Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Stability of pPBS and pPBS with medium. Concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 (right y-axis) and cell cytotoxicity of the three cell lines (left y-axis) as a function of time after treatment, to evaluate the stability of pPBS and of pPBS with medium, for a gap of 15 mm and a gas flow rate of 1 slm (i.e., condition 3 of Table 1). The concentrations and percentages are plotted as the mean of at least three repetitions, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean.

In addition, the concentration of NO2 − was also determined when pPBS was added to the cell medium immediately after treatment, showing again a stable concentration for at least 2 hours (see Fig. 8). Unfortunately, we could not determine the concentration of H2O2 in this case, as mentioned above. However, when pPBS is added to cell medium directly after treatment, the percentage cell cytotoxicity is lower when pPBS + medium is applied to the cancer cells after 30–60 min. This suggests that the reactive species in pPBS responsible for cell death react with organic molecules in the medium, so that pPBS loses part of its anti-cancer capacity when it is added to cell medium. As the concentration of NO2 − in pPBS + medium remains constant, the reduced cell cytotoxicity will be attributed to other reactive species, possibly H2O2, as it was reported that the H2O2 concentration in PAM drops when kept at room temperature33,63. Indeed, Yan et al.34 investigated the instability of PAM and found that H2O2 reacts with cysteine and methionine resulting in a lower anti-cancer capacity of the cell media. As mentioned above, we could not measure the H2O2 concentraton in medium + pPBS, so we cannot conclude whether a drop in H2O2 concentraton is causing this reduced cell cytotoxicity. As the concentration of H2O2 in pPBS (without medium) remains stable at room temperature for at least 2 hours (see Fig. 8), we tentatively conclude that PBS is a better way of storage for plasma species than cell medium itself, and thus, that pPBS could be more suitable for practical applications in a clinical setting than PAM.

Conclusion

We measured the chemical composition, more specifically the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2, of plasma-treated PBS (pPBS) with the kINPen®IND plasma jet, for different values of gas flow rate, gap and plasma treatment time, and we also evaluated the effect of this pPBS on cancer cell cytotoxicity for three different GBM cell lines, i.e., U251, LN229 and U87, at exactly the same plasma treatment conditions. This should allow us to draw conclusions on the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS, and on the role of the two above-mentioned plasma species in pPBS for killing cancer cells.

First, it is clear from our experiments that varying the operating conditions during plasma treatment leads to different ratios of H2O2 and NO2 − concentrations in pPBS, which can be important to consider when we know the exact role of individual species on cancer cell cytotoxicity and on their selectivity towards normal cells. To explain the generation processes of both H2O2 and NO2 −, we used a 0D chemical kinetics model. We found that the H2O2 concentration is mostly determined by the time needed for OH radicals to reach the liquid (affected by the gap and flow rate). Indeed, this determines whether the OH radicals will recombine into H2O2 (at high OHliquid concentrations) or whether they will be consumed by N-species, forming HNO2 −HNO3. For the NO2 − concentration, on the other hand, our model predicts that (i) by increasing the flow rate, fewer ambient air species are able to diffuse into the plasma plume, thereby lowering the NO2 − concentration, and (ii) by increasing the gap, more O3 will be generated, which will consume NO2 −, hence again lowering the NO2 − concentration.

Furthermore, our experiments revealed that H2O2 is a major contributor to cancer cell cytotoxicity while NO2 − plays a minor role, but other reactive species should also play a role in the anti-cancer activity of pPBS. A synergistic effect between H2O2 and NO2 − is found for the U87 cell line, but not for the U251 and LN229 cell lines. This fact, in combination with the trends of NO2 − and H2O2 concentration and percentage cell cytotoxicity as a function of different parameters, seems to suggest that H2O2 is a more important species for the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS than NO2 −, although assessing the concentrations of other plasma species, such as NO3 − and ONOO−, in pPBS is required in the future to draw final conclusions on the role of various plasma species in the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS. In this context, it is worth to mention that we also tried to measure the O3 concentration in pPBS, but that no signal could be detected. This suggests that O3, while it may be brought into the solution with the plasma gas, will probably rapidly disappear from it (likely back into the gas phase). Thus we may conclude that O3 might not play an important role in the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS.

Table 5 summarizes the results of the effects of all plasma treatment parameters on the NO2 − and H2O2 concentrations in pPBS, and on the cell cytotoxicity of the three different cancer cell lines. Increasing the gap results in lower concentrations of both NO2 − and H2O2, as well as reduced cell cytotoxicity. This is logical because the plasma species are not so efficiently transferred into the liquid, which is less effective for killing the cancer cells. Increasing the gas flow rate leads to a drop in the NO2 − concentration, because this species will not be formed so efficiently in the gas phase, as the N2 and O2 from the surrounding air come less in contact with the reactive plasma species. On the other hand, a higher gas flow rate yields a higher H2O2 concentration and also more cell cytotoxicity. This indicates that the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS is more related to the presence of H2O2 in the liquid than to the presence of NO2 −. Increasing the plasma treatment time yields a more or less linear increase in both the NO2 − and H2O2 concentrations in pPBS, and in the percentage cell cytotoxicity, except for the U87 cell line, although it is a bit dangerous to draw final conclusions on the linearity for the cancer cell cytotoxicity, based on only a few data points.

Table 5.

Summary. The effect of gap, gas flow rate, plasma treatment time, the occurrence of discharges at the liquid surface, and the stability of pPBS and pPBS with medium, on the concentrations of NO2 − and H2O2 in pPBS and on the anti-cancer capacity of pPBS for three different cancer cell lines.

| NO2 − | H2O2 | U251 | LN229 | U87 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap ↗ | ↘ | ↘ | ↘ | ↘ | ↘ |

| Gas flow rate ↗ | ↘ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ |

| Effect of plasma treatment time: ± linear? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Discharges at the liquid surface | ↗ × 2 | ↗ × 4 | ↗ ≥ × 2 | ↗ ≥ × 2 | ↗ ≥ × 2 |

| Stability of pPBS? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Stability of pPBS + medium? | ✓ | ? | × | × | × |

We also investigated the effect of the occurrence of discharges at the liquid surface on the NO2 − and H2O2 concentrations in pPBS and on the cancer cell cytotoxicity, and observed that these discharges have a significant influence, yielding a factor 2 and 4 higher NO2 − and H2O2 concentration in the liquid, as well as at least a factor 2 higher anti-cancer capacity of the pPBS. Indeed, these discharges allow electrons to reach the liquid and to produce more reactive species in the liquid due to electron impact reactions. This is important to realize as a small variation of the gap (in our case between 10 and 15 mm) results in either the presence or absence of discharges at the liquid surface.

Finally, the fact that pPBS is stable at room temperature for at least 2 hours, while pPBS with medium is not, indicates that pPBS might be a more suitable storage medium for practical applications in a clinical setting than PAM, which is until now most often applied.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO) Flanders (Grant No. 11U5416N), the Research Council of the University of Antwerp and the European Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship “LTPAM” within Horizon2020 (Grant No. 743151). Finally, we would like to thank P. Attri and A. Privat Maldonado for the valuable discussions.

Author Contributions

W.V.B., Y.G. and S.V. designed the experiments. W.V.B. performed the experiments. J.V.d.P. designed and performed the simulations. W.V.B., J.V.d.P. and A.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16758-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wilma Van Boxem, Email: wilma.vanboxem@uantwerpen.be.

Annemie Bogaerts, Email: annemie.bogaerts@uantwerpen.be.

References

- 1.Schlegel J, Köritzer J, Boxhammer V. Plasma in cancer treatment. Clinical Plasma Medicine. 2013;1:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cpme.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barekzi N, Laroussi M. Effects of low temperature plasmas on cancer cells. Plasma Process. Polym. 2013;10:1039–1050. doi: 10.1002/ppap.201300083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratovitski EA, et al. Anti-cancer therapies of 21st century: novel approach to treat human cancers using cold atmospheric plasma. Plasma Process. Polym. 2014;11:1128–1137. doi: 10.1002/ppap.201400071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu X, et al. Reactive species in non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasmas: generation, transport, and biological effects. Phys. Rep. 2016;630:1–84. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2016.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SJ, Chung TH, Bae SH, Leem SH. Induction of apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by a pulsed atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:023702. doi: 10.1063/1.3462293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma for selectively ablating metastatic breast cancer cells. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e73741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JY, et al. Apoptosis of lung carcinoma cells induced by a flexible optical fiber-based cold microplasma. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011;28:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SJ, Joh HM, Chung TH. Production of intracellullar reactive oxygen species and change of cell viability induced by atmospheric pressure plasma in normal and cancer cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;103:153705. doi: 10.1063/1.4824986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar N, et al. The action of microsecond-pulsed plasma-activated media on the inactivation of human lung cancer cells. J. Phys D: Appl. Phys. 2016;49:115401. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/49/11/115401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barekzi N, Laroussi M. Dose-dependent killing of leukemia cells by low-temperature plasma. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2012;45:422002. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/45/42/422002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partecke LI, et al. Tissue tolerable plasma (TTP) induces apoptosis in pancreatic cells in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:473. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Li M, Zhou R, Feng K, Yang S. Ablation of liver cancer cells in vitro by a plasma needle. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;93:021502. doi: 10.1063/1.2959735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao S, et al. Atmospheric pressure room temperature plasma jets facilitate oxidative and nitrative stress and lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress dependent apoptosis in HepG2 cells. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e73665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan J, Lu X, He G. The selective effect of plasma activated medium in an in vitro co-culture of liver cancer and normal cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2017;121:013302. doi: 10.1063/1.4973484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka H, et al. Plasma-activated medium selectively kills glioblastoma brain tumor cells by down-regulating a survival signaling molecule, AKT kinase. Plasma Med. 2011;1:265–277. doi: 10.1615/PlasmaMed.2012006275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandamme M, et al. ROS implication in a new antitumor strategy based on non-thermal plasma. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;130:2185–2194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan D, et al. The role of aquaporins in the anti-glioblastoma capacity of the cold plasma-stimulated medium. J. Phys D: Appl. Phys. 2017;50:055401. doi: 10.1088/1361-6463/aa53d6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeylen S, et al. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment of melanoma and glioblastoma cancer cells. Plasma Process. Polym. 2016;13:1195–1205. doi: 10.1002/ppap.201600116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn HJ, et al. Atmospheric-pressure plasma jet induces apoptosis involving mitochondria via generation of free radicals. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishaq M, et al. Atmospheric gas plasma-induced ROS production activates TNF-ASK1 pathway for the induction of melanoma cancer cell apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:1523–1531. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-10-0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fridman G, et al. Floating electrode dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air promoting apoptotic behavior in melanoma skin cancer cell lines. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2007;27:163–176. doi: 10.1007/s11090-007-9048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim GC, et al. Air plasma coupled with antibody-conjugated nanoparticles: a new weapon against cancer. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2009;42:032005. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/42/3/032005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HJ, et al. Degradation of adhesion molecules of G361 melanoma cells by a non-thermal atmospheric pressure microplasma. New J. Phys. 2009;11:115026. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/11/11/115026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan D, et al. Toward understanding the selective anticancer capacity of cold atmospheric plasma—a model based on aquaporins (Review) Biointerphases. 2015;10:040801. doi: 10.1116/1.4938020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Paal J, Neyts EC, Verlackt CCW, Bogaerts A. Effect of lipid peroxidation on membrane permeability of cancer and normal cells subjected to oxidative stress. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:489–498. doi: 10.1039/C5SC02311D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Paal J, Verheyen C, Neyts EC, Bogaerts A. Hampering effect of cholesterol on the permeation of reactive oxygen species through phospholipids bilayer: possible explanation for plasma cancer selectivity. Sci. Reports. 2017;7:39526. doi: 10.1038/srep39526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato T, Yokoyama M, Johkura K. A key inactivation factor of HeLa cell viability by a plasma flow. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 2011;44:372001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/44/37/372001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canal C, et al. Plasma-induced selectivity in bone cancer cells death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;110:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan D, et al. Controlling plasma stimulated media in cancer treatment application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;105:224101. doi: 10.1063/1.4902875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan D, et al. Principles of using cold atmospheric plasma stimulated media for cancer treatment. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18339. doi: 10.1038/srep18339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan D, Nourmohammadi N, Talbot A, Sherman JH, Keidar M. The strong anti-glioblastoma capacity of the plasma-stimulated lysine-rich medium. J. Phys D: Appl. Phys. 2016;49:274001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/49/27/274001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adachi T, et al. Plasma-activated medium induces A549 cell injury via a spiral apoptotic cascade involving the mitochondrial-nuclear network. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;79:28–44. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan D, et al. Stabilizing the cold plasma-stimulated medium by regulating medium’s composition. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26016. doi: 10.1038/srep26016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wende K, et al. Identification of the biologically active liquid chemistry induced by a nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Biointerphases. 2015;10:029518. doi: 10.1116/1.4919710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boehm D, Heslin C, Cullen PJ, Bourke P. Cytotoxic and mutagenic potential of solutions exposed to cold atmospheric plasma. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21464. doi: 10.1038/srep21464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan D, et al. The specific vulnerabilities of cancer cells to the cold atmospheric plasma-stimulated solutions. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4479. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04770-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girard P-M, et al. Synergistic effect of H2O2 and NO2 in cell death induced by cold atmospheric He plasma. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29098. doi: 10.1038/srep29098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka H, et al. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma activates lactate in Ringer’s solution for anti-tumor effect. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36282. doi: 10.1038/srep36282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruggeman PJ, et al. Plasma-liquid interactions: a review and roadmap. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016;25:053002. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/25/5/053002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winter J, et al. Tracking plasma generated H2O2 from gas into liquid phase and revealing its dominant impact on human skin cells. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014;47:285401. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/47/28/285401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takamatsu T, et al. Investigation of reactive species using various gas plasmas. RSC Adv. 2014;4:39901. doi: 10.1039/C4RA05936K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorbanev Y, O’Connell D, Chechik V. Non-thermal plasma in contact with water: the origin of species. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22:3496–3505. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tresp H, Hammer MU, Winter J, Weltmann K-D, Reuter S. Quantitative detection of plasma-generated radicals in liquids by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2013;46:435401. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/46/43/435401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama M, Johkura K, Sato T. Gene expression responses of HeLa cells to chemical species generated by an atmospheric plasma flow. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;450:1266–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohades S, Laroussi M, Sears J, Barekzi N, Razavi H. Evaluation of the effects of a plasma activated medium on cancer cells. Phys. Plasmas. 2015;22:122001. doi: 10.1063/1.4933367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Judée F, et al. Short and long time effects of low temperature plasma activated media on 3D multicellular tumor spheroids. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21421. doi: 10.1038/srep21421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adachi T, et al. Iron stimulates plasma-activated medium-induced A549 cell injury. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20928. doi: 10.1038/srep20928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurake N, et al. Cell survival of glioblastoma grown in medium containing hydrogen peroxide and/or nitrite, or in plasma-activated medium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;605:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agnihotri S, et al. Glioblastoma, a brief review of history, molecular genetics, animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013;61:25–41. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Louis DN, et al. The2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stupp R, et al. Effect of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bekeschus S, Schmidt A, Weltmann K-D, von Woedtke T. The plasma jet kINPen – a powerful tool for wound healing. Clin. Plasma Med. 2016;4:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cpme.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mann MS, et al. Introduction to DIN-specification 91315 based on the characterization of the plasma jet kINPen® MED. Clin. Plasma Med. 2016;4:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpme.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eisenberg GM. Colorimetric determination of hydrogen peroxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed. 1943;15:327–328. doi: 10.1021/i560117a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lukes P, Dolezalova E, Sisrova I, Clupek M. Aqueous-phase chemistry and bactericidal effects from an air discharge plasma in contact with water: evidence for the formation of peroxynitrite through a pseudo-second-order post-discharge reaction of H2O2 and HNO2. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2014;23:015019. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/23/1/015019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Satterfield CN, Bonnell AH. Interferences in titanium sulfate method for hydrogen peroxide. Anal. Chem. 1955;27:1174–1175. doi: 10.1021/ac60103a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anbar M, Taube H. Interaction of nitrous acid with hydrogen peroxide and with water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954;76:6243–6247. doi: 10.1021/ja01653a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fox JB. Kinetics and mechanisms of the griess reaction. Anal. Chem. 1979;51:1493–1502. doi: 10.1021/ac50045a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vichai V, Kirtikara K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat. Protoc. 2016;1:1112–1116. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibicka L, Didik J. Catalytic scavenging of peroxynitrite by catalase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:1375–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeda S, et al. Intraperitoneal administration of plasma-activated medium: proposal of a novel treatment option for peritoneal metastasis from gastric cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017;24:1188–1194. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohades S, Barekzi N, Razavi H, Marathammathu V, Laroussi M. Temporal evaluation of the anti-tumor efficiency of plasma-activated medium. Plasma Process. Polym. 2016;13:1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/ppap.201600118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information).