To the Editor,

We are delighted to have the opportunity to respond to the letter by Gilks et al. (Gilks et al., 2017). They argue first that historical pathological entities do not map seamlessly to modern day diagnostic categories, which are not only based on expert review by specialist gynecological pathologists but are also increasingly supported by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Second, that the misclassification of biologically indolent tumors as high grade serous (HGS) ovarian cancers may explain the uncharacteristically excellent survival figures we report (Ryan et al., 2017). And third, that our paper may inadvertently lead to the universal screening of HGS ovarian cancers for Lynch syndrome, when this is not indicated.

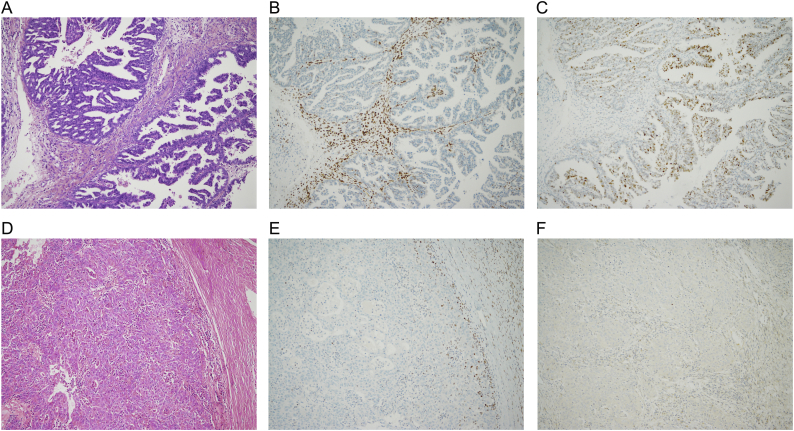

To address the first point, we undertook contemporary slide review and supporting IHC for a subset of our cases (12/37, 30%). In so doing, we were able to compare the original histological subtype with up-to-date expert gynecological pathology review backed up by IHC. Unfortunately, we were unable to retrieve slides or tissue blocks for all women, particularly those whose surgery was performed elsewhere and more than 15 years ago. Table 1 shows the results of our analysis. Pathology review confirmed accurate diagnoses for 10 of the 12 cases (83%), including six endometrioid tumors, one clear cell, one carcinosarcoma, one mixed endometrioid/clear cell tumor and one poorly differentiated carcinoma which was difficult to reliably subtype* (*Fig. 1D). The two discrepant cases were an endometrioid tumor originally misclassified as a ‘serous cystadenocarcinoma’, and a ‘serous papillary carcinoma’, which had cytology of low-to-intermediate grade on review and wild type p53 staining favouring a final classification of low grade serous carcinoma** (**Fig. 1A). Our data are in keeping with those of other case series of Lynch syndrome-associated ovarian cancer, where endometrioid morphology predominates, but clear cell, serous and mixed histotypes are also described (Grindedal et al., 2010, Coppola et al., 2012, Zhai et al., 2008, Rosenthal et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Contemporary expert gynecological pathology review.

| Study ID | Germline mutation | MMR loss by IHC | Original histotype | Histology review | Supporting IHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | MLH1 | MLH1 & PMS2 | Clear cell | Agree | Not performed |

| 4 | MLH1 | MLH1 | Endometrioid | Agree | Confirms |

| 11 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | Agree | ER, PR positive Null type p53 |

| 13 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Endometrioid | Agree | Confirms |

| 16 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Endometrioid | Agree | Not performed |

| 19 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Serous papillary | Low grade serous | Wild type p53 |

| 20 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Endometrioid | Agree | Not performed |

| 22 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Carcinosarcoma | Agree | Confirms |

| 23 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Endometrioid | Agree | Not performed |

| 27 | MSH2 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Serous cystadenocarcinoma | Endometrioid | ER, PR positive WT1 negative Wild type p53 |

| 32 | MSH6 | MSH2 & MSH6 | Mixed clear cell/endometrioid | Agree | Confirms |

| 37 | PMS2 | PMS2 | Mixed | Agree | Confirms |

Fig. 1.

Lynch syndrome-associated ovarian tumors with supporting IHC.

A) H + E: Low grade serous carcinoma with a glandular, cribriform and papillary architecture, comprising cells with low to intermediate grade cytological atypia. B) Immunohistochemical staining shows loss of MSH2. C) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates wild-type p53, in keeping with low grade serous carcinoma. D) H + E: Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with a glandular and solid architecture. E) Immunohistochemical staining shows loss of MSH2. F) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates null-type p53.

Regarding the second point, we speculated that the mismatch repair (MMR) status of the tumors could help differentiate those that had arisen because of mismatch repair deficiency from those that had arisen via a different pathway. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, all of the tumors showed MMR deficiency in keeping with their inherited mutation, including the women whose tumors showed serous morphology. This supports the hypothesis that all have arisen as a consequence of Lynch syndrome. We and others have shown that Lynch syndrome-associated ovarian cancer presents at an earlier age and stage and demonstrates excellent survival rates compared with sporadic ovarian cancers (Moller et al., 2017, Lynch et al., 2009). This may be due to early detection through surveillance, good biology, enhanced tumor immunogenicity and responsiveness to current treatments (Lynch et al., 2009). By contrast, BRCA-associated ovarian cancers have a poor prognosis irrespective of early detection and treatment (Finch et al., 2014). There is no doubt that germline mutations in MMR and BRCA genes are only similar because they both predispose a woman to developing ovarian cancer; in every other respect, they are quite different.

Finally, we do not recommend that all HGS ovarian cancers are routinely screened for Lynch syndrome. The prevalence of Lynch syndrome in women with ovarian cancer is low. However, genetic predisposition syndromes should always be considered as an underlying cause for non-mucinous invasive epithelial ovarian cancer in young women, those with a strong family history of breast, endometrial, ovarian and/or colorectal cancer, or those with metachronous or synchronous cancers. And indeed, in the spirit of P4 medicine, the sequencing panel chosen should reflect the unique clinical context of each individual woman, rather than being driven purely by tumor histotype.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Coppola D., Nicosia S.V., Doty A. Uncertainty in the utility of immunohistochemistry in mismatch repair protein expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4963–4969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch A.P., Lubinski J., Moller P. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:1547–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Gilks C.B., Clarke B.A., Foulkes W.D. Ovarian carcinoma histotype in lynch syndrome. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2017;20:140–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindedal E.M., Renkonen-Sinisalo L., Vasen H. Survival in women with MMR mutations and ovarian cancer: a multicentre study in lynch syndrome kindreds. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:99–102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.068130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch H.T., Casey M.J., Snyder C.L. Hereditary ovarian carcinoma: heterogeneity, molecular genetics, pathology and management. Mol. Oncol. 2009;3:97–137. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller P., Seppala T., Bernstein I. Cancer incidence and survival in lynch syndrome patients receiving colonoscopic and gyaecological surveillance: first report from the prospective lynch syndrome database. Gut. 2017;66:464–472. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal A.N., Fraser L., Manchanda R. Results of annual screening in phase I of the United Kingdom familial ovarian cancer screening study highlight the need for strict adherence to screening schedule. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:49–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan N.A.J., Green K., Evans D.G., Crosbie E.J. Pathological features and clinical behaviour of lynch syndrome-associated ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017;144:491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Q.J., Rosen D.G., Lu K., Liu J. Loss of DNA mismatch repair protein hMSH6 in ovarian cancer is histotype-specific. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2008;1:502–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]