Highlights

-

•

Entero-vesical fistulas (EVFs) represent an uncommon complication of Crohn’s disease.

-

•

EVFs affects mostly men patients.

-

•

Conservative treatment improves symptoms but is associated with low rate of healing.

-

•

Surgical approach is usually necessary, establishing long-term remission.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Entero-vesical fistula, Bladder, Surgical treatment

Abstract

Background

Entero-vesical fistula (EVF) is an abnormal link between the enteric lumen and the urinary bladder. Crohn's disease (CD) represents, nowadays, the most common cause in the formation of this fistula.

Materials and methods

The aim of this study was to describe the diagnostic and treating modalities applied in nine patients with CD and EVFs, the clinical/epidemiological features of this clinical entity and to perform a systemic review of the literature, concerning the diagnosis and treatment of this complication.

Results

The medical records of eight men and one woman (mean age 42 ± 12 years) with EVFs were analyzed. The terminal ileum and the ileocecal region were affected in three and six cases, respectively. The most common symptoms were pneumaturia, fecaluria, fever, urinary urgency and abdominal pain. The diagnosis was suspected by abdominal CT scan and by indirect findings of bladder infection in cystoscopy. MRI with concurrent cystography set the diagnosis in three patients. Colonoscopy was not helpful. Conservative treatment, including administration of antibiotics and immunosuppressive agents in all patients and anti-TNF-a agent (infliximab) in six patients, was ineffective. Surgical treatment was applied in seven cases (77.8%), including fistula repair in all patients, drainage of coexistent intraabdominal abscess in two, small bowel resection in four and ileocecectomy in two cases.

Conclusion

EFVs are uncommon but potentially dangerous complications of CD. Abdominal CT scan and cystoscopy are the most commonly used diagnostic modalities. Surgical treatment seems to be unavoidable in most cases, although medical treatment could also benefit a small cohort of patients.

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) represents a chronic, transmural, inflammatory disease that may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. The disease has various clinical manifestations; however, the presence of abscesses, fistulas and strictures is often quite serious and difficult to manage [1], [2].

Internal fistulas develop in 5–10% of patients with CD. Entero-vesical (EVF) fistulas represent the most common form of fistula affecting the urinary tract, probably due to the proximity of the ileum and the dome of the bladder [3]. CD is the main cause of fistulas developing between the ileum and bladder and the third most common cause of fistula formation between the colon and the bladder [4], [5], [6], [7]. The importance of this complication is highlighted by the fact that it could possibly represent the only initial evidence of Crohn’s disease [8].

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical entity of EVFs, to present the diagnostic and therapeutic modalities applied in a cohort of nine patients with CD and ileo-vesical fistulas and to review, in detail, the relevant literature.

2. Patients and methods

Since 2005, when the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Unit was established at our Department, 206 patients with CD are being followed-up. Among them, nine patients (2.4%, 8 men and 1 woman) with mean age of 42 ± 12 years were diagnosed with EVFs. The disease was located in the terminal ileum in three patients and in the ileocecal region in six. CD was active in all cases (CDAI >220 points) at the time of diagnosis.

The main clinical symptoms included pneumaturia (100%), fecaluria (78%), symptoms of urinary infection (55%), fever (44%), abdominal pain (22%) and urinary urgency (18%). Recurrent urinary infection (≥two episodes within 6 months), accompanied by fever and dysuria were the main reasons for the referral to our unit. Other mild symptoms of the patients included anorexia, fatigue and loss of weight.

3. Results

3.1. Diagnostic modalities

Although cystoscopy was indicative of cystitis in all patients, there was no clear evidence of the fistula. A protruding area of granulomatous tissue (sized >1 cm) was seen in two cases, which was clinically alike to urinary papilloma. However, histology revealed only the presence of granulomatous tissue.

CT scan showed increased thickness of the wall of the bowel wall and narrowed enteric lumen, without any clear evidence of the tract of the fistula.

MRI with concurrent cystography was performed in four cases and the results were compatible with EVF in 3 out of 4 patients (75%).

Barium enema was applied in two cases, without providing any clinical assistance.

Urinary examination exhibited abundance of leucocytes and red cells, as well as the presence of fecal material. Urinary culture was positive for Escherichia Coli in all cases.

3.2. Therapeutic approaches

The maintenance treatment of the underlying CD consisted of azathioprine in five patients and oral mesalazine in four. Antibiotics were administered in all patients after the diagnosis of the fistula. Ciprofloxacin was the preferred antibiotic in patients with afebrile urinary tract infection or asymptomatic pyuria. In six cases, the previously positive urinary cultures became negative. The biologic agent infliximab against the tumor necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF-α) was administered in three cases, resulting in temporary improvement of the symptoms without, however, achieving closure of the fistula.

Surgical treatment was applied in seven patients (77.8%). Two patients were considered unfit for surgery and they were put on long-term antibiotic therapy. No laparoscopic approach was utilized. Surgery included detachment of the inflamed bowel loop from the bladder and primary repair (suturing) of the fistula’s orifice, in all cases. Drainage of coexistent mesenteric abscess was performed in two cases. Resection of the involved segment of the small bowel was deemed necessary in four patients, followed by a side-to-side anastomosis. In two patients, an ileocecectomy with ileo-ascending anastomosis was performed (Fig. 1). No temporal ostomy was done. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 9.2 ± 4.1 days. The surgical outcome was favorable in all cases, with no perioperative morbidity and mortality.

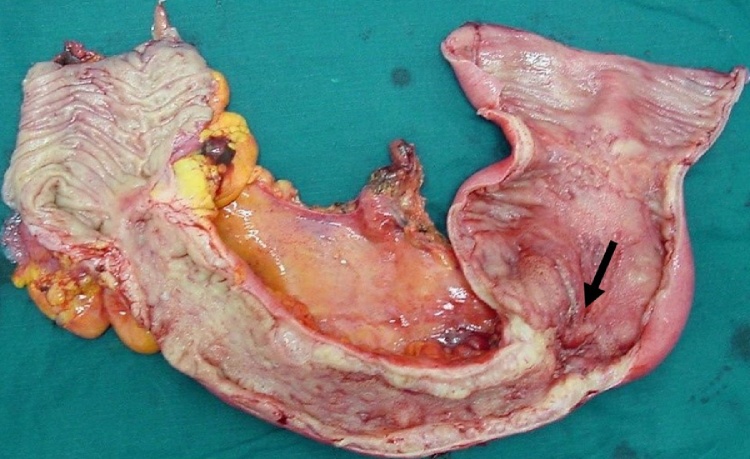

Fig. 1.

Surgical specimen (ileocecectomy) of a patient with entero-vesical fistula.

The inflamed part of the bowel and the site of the fistula are shown (arrow).

3.3. Follow-up

All patients were put on the same maintenance therapy for CD, postoperatively. Urine analysis and culture were the most important diagnostic tests for early recognition of any urinary infection, possibly indicating recurrence, postoperatively. No recurrence of EVFs or any other complications were documented in a mean follow-up period of 42 ± 18 months.

4. Discussion

Although a significant proportion of patients with CD develop urinary complications, the appearance of EVFs is quite uncommon. In a relevant study by Ben-Ami et al. [9], 16 among 312 patients with CD developed EVFs (1.9%). In their series of 400 patients with CD, Gruner et al. [7] documented eight patients who developed EVFs (2%). However, lower rates of this clinical entity were recently described. An incidence of 1.6% (97 out of 6081) of EVFs among patients with CD was documented by Taxonera et al. [10] in their multicentered, retrospective study. The incidence of EVFs in our series (2.4%) is quite similar with that found in the previously mentioned reports.

EVFs affect mainly men, with the reported incidence reaching up to 75% [11]. This finding was also validated in our series with an 88% male preponderance. The different anatomy, of the usually affected area, in women (presence of the uterus between the bladder and the bowel), is a possible reasonable explanation.

Increased body mass index (BMI) is also suggested by some studies as a predisposing factor [12]. However, only two of our patients had body mass index (BMI) above 25 kg/m2. It is also well established that in the great majority of patients, the terminal ileum is affected, a finding also evident in our study. In fact, the terminal ileum or the ileocecal were affected by CD in all our cases.

The main clinical symptoms documented in our series were pneumaturia, fecaluria and signs of urinary infection, as also described by similar reports [9], [11].

Regarding the optimal diagnostic modalities for this clinical entity, it has been suggested that CT scan, or even contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, have good sensitivity and specificity for revealing urologic complications arising in patients with CD [6], [13]. However, the detection of EVFs by CT scan is not as sensitive as in cases of entero-cutaneous or perianal fistulas. CT scan usually identifies indirect signs of involvement of the terminal ileum, such as narrowed lumen and thickness of the bowel wall, without clear evidence of the existence of a fistula.

Cystoscopy and/or cystography also seem to be helpful in identifying the fistulous tract and its association with the orifices of the ureters [14]. Some reports suggest that cystoscopy and urine cytology for fecal material should be the first-line investigations in all patients with suspected EVFs [15]. Furthermore, the diagnostic combination of cystoscopy and CT scan could offer diagnostic yield up to 74% [16]. In the current study, cystoscopy did not offer significant diagnostic assistance, except for the recognition of infection (cystitis). In two cases, the protruding granulomatous tissue seen inside the bladder was erroneously considered as a benign cystic tumor (papilloma), a case quite similar to that described by Benchekroun et al. [17]. In their report, a patient with CD and urinary symptoms, during diagnostic evaluation for EVF, underwent cystoscopy revealing a tumor of the bladder with no presence of fistula orifice. A transurethral resection of the tumor was performed. An inflammatory pseudotumor of the urinary bladder was diagnosed by histology, because of the co-existence of a sigmoid-vesical fistula, finally diagnosed with MRI [17].

Recently, the application of indocyanine green has been proposed as an alternative diagnostic tool for patients suspected for EVFs. After administration of the substance by mouth or intrarectally, it can be detected in the urine by a colorimeter, with sensitivity reaching up to 92% [18].

The treatment of “silent” EVFs may be conservative, initially. However, symptomatic fistulas often require augmentation of the conservative therapy, often coupled with surgical intervention. Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, myophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine Α, tacrolimus and infliximab have been used in various studies for the treatment of EVFs in patients with CD, but with limited success [2].

In our series, after the diagnosis of EVFs, antibiotics were administered in all patients.

In three cases, the additional administration of infliximab resulted in better temporary control of the symptoms, but without closure of the fistula. In the study of Taxonera et al. [10], 35% of the patients received anti-TNF-α therapy and nearly half of them achieved sustained remission (median follow-up 35 months), without the need for surgery. In a recent systemic review of 23 studies, Kaimakliotis et al. [19] reported 65.9% complete response, 20.5% partial response and 13.6% no response to medical therapy in a total of 44 patients with EVFs. Anti-TNF-α therapy was given in 14 patients, with complete, partial and no-response rates of 57.1%, 35.7% and 7.1%, respectively. Based on these results, medical therapy alone or in combination with surgery seems to be of benefit in some patients. However, the disappointing results obtained by other authors [20], the small size and the low quality of the published studies, lead the authors to suggest that no consensus statement can be made regarding the optimal treatment [19].

Surgical treatment was applied in 77.8% of patients, in our cohort. Various rates of surgical treatment have been reported in the literature. In a recent study, over than 80% of patients underwent surgical intervention, with recorded remission in almost all of them [10]. Most researchers agree that medical therapy is the first choice in patients suffering by EFVs alone. However, in cases with EVFs and other CD complications, surgical intervention will eventually be necessary [21].

According to ECCO guidelines the laparoscopic approach is preferred in ileocolonic resections in CD, but the available experience in treating complicated cases with internal fistulas is scarce [22], [23]. In most studies, there was no attempt to use laparoscopic surgery in any patient to treat fistulas to the urinary tract. According to some authors, laparoscopic bladder-preserving surgery is feasible in cases of EVFs and may be proposed as the first choice in such cases [24]. We strongly believe that, as in cases of duodenal fistula involvement, most entero-vesical fistulas are associated with higher conversion rates. Dense adhesions in the pelvis and difficulties obtaining adequate access around a phlegmon adherent to the low pelvis is usually the reason for conversion. Therefore, although an initial cursory laparoscopy may be feasible to evaluate the ability to mobilize the phlegmon, the open approach is the preferred option in most cases.

5. Conclusions

EVFs, although rare in patients with CD, is a complication requiring prompt diagnosis and therapy. The diagnosis is based mainly on clinical symptoms and the indirect findings of CT scan and cystoscopy. Pneumaturia is a strong clinical indicator of EVFs. This clinical entity affects almost exclusively men with location of CD in the terminal ileum. Conservative treatment, including administration of anti-TNF-α agents, offers small benefit, especially in symptomatic fistulas and advanced, complicated disease. Surgical treatment is required in most cases, mainly consisting by suturing the wall of the bladder and resection of the involved segment of the bowel. Surgery induces sustained remission and is associated with extremely low rates of recurrence.

Statement

The manuscript has been reported in line with the PROCESS criteria [25].

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding for your research

No funding.

Ethical approval

Approval by the ethics committee of our institution (Ref No 05234) (Iaso General Hospital, Athens, Greece).

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Constantine Vagianos: Study design, data collection.

George Malgarinos: Data collection, writing.

Charalampos Spyropoulos: Data analysis, writing.

John K Triantafillidis: Study design, data collection, writing.

Guarantor

John K Triantafillidis.

References

- 1.Triantafillidis J.K., Emmanouilidis A., Nicolakis D., Cheracakis P., Kogevinas M., Merikas E. Surgery for Crohn’s disease in Greece: a follow-up study of 79 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1072–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triantafillidis J.K., Emmanouilidis A., Manousos O., Nicolakis D., Kogevinas M. Clinical patterns of Crohn’s disease in Greece: a follow-up study of 155 cases. Digestion. 2000;61:121–128. doi: 10.1159/000007744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade G., Zaslau S., Janse R. A review of urinary fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Can. J. Urol. 2014;21:7179–7184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz D.A., Loftus E.V., Jr, Tremaine W.J. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County Minessota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875–880. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy C., Tremaine W.J. Management of internal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2002;8:106–111. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manganiotis A.N., Banner M.P., Malkowicz S.B. Urologic complications in Crohn’s disease. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2001;81:197–215. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruner J.S., Sehon J.K., Johnson L.W. Diagnosis and management of enterovesical fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am. Surg. 2002;68:714–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullis P., Mullassery D., Baillie C., Corbett H. Crohn’s disease presenting as enterovesical fistula. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Ami H., Ginesin Y., Behar D.M., Fischer D., Edoute Y., Lavy A. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract complications in Crohn’s disease: an experience of over 15 years. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;16:225–229. doi: 10.1155/2002/204614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taxonera C., Barreiro-de-Acosta M., Bastida G. Outcomes of medical and surgical therapy for entero-urinary fistulas in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:657–662. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solem C.A., Loftus E.V., Jr, Tremaine W.J., Pemberton J.H., Wolff B.G., Sandborn W.J. Fistulas to the urinary system in Crohn’s disease: clinical features and outcomes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2300–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blain A., Cattan S., Beaugerie L., Carbonnel F., Gendre J.P., Cosnes J. Crohn’s disease clinical course and severity on obese patients. Clin. Nutr. 2002;21:51–57. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2001.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruffolo C., Angriman I., Scarpa M., Polese L., Pagano D., Barollo M., Bertin M., D’Amico D.F. Urologic complications in Crohn’s disease: suspicion criteria. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyashita M., Hao K., Matsuda T., Hayashi T., Onda M. Enterovesical fistula caused by inflammatory bowel disease. Nippon Ika Daigaku Zasshi. 1992;59:467–470. doi: 10.1272/jnms1923.59.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels I.R., Bekdash B., Scott H.J., Marks C.G., Donaldson D.R. Diagnostic lessons learnt from a series of enterovesical fistulae. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:459–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solem C.A., Loftus E.V., Jr, Tremaine W.J., Pemberton J.H., Wolff B.G., Sandborn W.J. Fistulas to the urinary system in Crohn’s disease: clinical features and outcomes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2300–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchekroun A., el Alj H.A., Zannoud M., Jira H., Essayegh H., Nouini Y., Marzouk M., Faik M. Enterovesical fistula secondary to Crohn’s disease manifested by inflammatory pseudotumor of the bladder. Ann. Urol. 2003;37:180–183. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4401(03)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y.J., Mao R., Xie X.H. Intracavitary contrast-enhanced ultrasonography to detect enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:315–317. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaimakliotis P., Simillis C., Harbord M., Kontovounisios C., Rasheed S., Tekkis P.P. A systematic review assessing medical treatment for rectovaginal and enterovesical fistulae in crohn’s disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016;50:714–721. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Present D.H., Rutgeerts P., Targan S., Hanauer S.B., Mayer L., van Hogezand R.A., Podolsky D.K., Sands B.E., Braakman T., DeWoody K.L., Schaible T.F., van Deventer S.J. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W., Zhu W., Li Y., Zuo L., Wang H., Li N., Li J. The respective role of medical and surgical therapy for enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014;48:708–711. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dignass A., Van Assche G., Lindsay J.O., Lémann M., Söderholm J., Colombel J.F. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pokala N., Delaney C.P., Brady K.M., Senagore A.J. Elective laparoscopic surgery for benign internal enteric fistulas: a review of 43 cases. Surg. Endosc. 2005;19:222–225. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8801-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizushima T., Ikeda M., Sekimoto M., Yamamoto H., Doki Y., Mori M. Laparoscopic bladder-preserving surgery for enterovesical fistula complicated with benign gastrointestinal disease. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2012;6:279–284. doi: 10.1159/000339202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rajmohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., PROCESS Group Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]