Abstract

The alveolar epithelium consists of squamous alveolar type (AT) I and cuboidal ATII cells. ATI cells cover 95–98% of the alveolar surface, thereby playing a critical role in barrier integrity, and are extremely thin, thus permitting efficient gas exchange. During lung injury, ATI cells die, resulting in increased epithelial permeability. ATII cells re-epithelialize the alveolar surface via proliferation and transdifferentiation into ATI cells. Transdifferentiation is characterized by down-regulation of ATII cell markers, up-regulation of ATI cell markers, and cell spreading, resulting in a change in morphology from cuboidal to squamous, thus restoring normal alveolar architecture and function. The mechanisms underlying ATII to ATI cell transdifferentiation have not been well studied in vivo. A prerequisite for mechanistic investigation is a rigorous, unbiased method to quantitate this process. Here, we used SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice, in which ATII cells and their progeny express green fluorescent protein (GFP), and applied stereologic techniques to measure transdifferentiation during repair after injury induced by LPS. Transdifferentiation was quantitated as the percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATII-derived (GFP+) cells expressing ATI, but not ATII, cell markers. Using this methodology, the time course and magnitude of transdifferentiation during repair was determined. We found that ATI cell loss and epithelial permeability occurred by Day 4, and ATII to ATI cell transdifferentiation began by Day 7 and continued until Day 16. Notably, transdifferentiation and barrier restoration are temporally correlated. This methodology can be applied to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying transdifferentiation, ultimately revealing novel therapeutic targets to accelerate repair after lung injury.

Keywords: transdifferentiation, alveolar epithelium, lung injury and repair

The alveolar epithelium consists of squamous alveolar type (AT) I cells and cuboidal ATII cells. ATI cells cover 95–98% of the alveolar surface, thereby playing a critical role in barrier function, and are extremely thin, permitting efficient gas exchange (1). Perhaps in part due to their morphology, ATI cells are particularly susceptible to injury. During lung injury induced by various causes, ATI cells die and slough off (1–8), resulting in increased permeability, which, in the case of acute respiratory distress syndrome, leads to the influx of edema fluid and hypoxemia (9). Efficient epithelial repair is critical for reabsorption of edema and survival (10, 11), and is believed to prevent fibrosis (3, 12). However, there are no therapies to enhance re-epithelialization, in part because of our limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms that drive repair.

Re-epithelialization is orchestrated principally by ATII cells (4, 6, 7, 13–16) (under certain circumstances, other progenitors contribute [16–20]). Surviving ATII cells proliferate to replace lost cells, and, based on work by us (21) and others (22–25), the mechanisms that drive ATII cell proliferation are partially understood. However, once normal cell numbers are restored, some ATII cells must transdifferentiate into ATI cells to re-establish normal alveolar architecture (2, 6, 13–17). Transdifferentiation is characterized by down-regulation of ATII cell markers, up-regulation of ATI cell markers, and cell spreading, resulting in a change in morphology from cuboidal to squamous. In fact, based on the known dimensions of ATII and ATI cells (26, 27), transdifferentiation requires massive cell spreading, yielding a cell that is greater than 100 times thinner and covers approximately 50 times more surface area. Transdifferentiation is of critical physiologic significance, as it results in re-epithelialization of the denuded alveolar surface after ATI cell loss, thus restoring barrier integrity, with a thin cell that permits efficient gas exchange by virtue of its squamous morphology (1). However, despite a few in vitro reports (28–30), the molecular mechanisms underlying transdifferentiation have rarely been studied in vivo. In vivo mechanistic studies using pharmacologic or genetic manipulation of specific molecular pathways would require stringent, unbiased quantification of transdifferentiation to ensure accurate conclusions.

A method to accurately and quantitatively measure transdifferentiation is stereology (31, 32), morphometric measurement of three-dimensional structures using two-dimensional tissue sections (33). Design-based stereology uses rigorous uniform sampling to ensure that the fraction of tissue analyzed is representative of the entire organ, a fundamental tenet of scientific investigation necessary to avoid bias and render accurate conclusions (31). Such an approach is imperative, particularly with growing concern about methodological rigor and reproducibility in biomedical science (34–37).

Here, we use SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice, in which ATII cells and all of their progeny express green fluorescent protein (GFP), and apply stringent stereologic methodology to rigorously measure ATII to ATI cell transdifferentiation during repair after lung injury. Transdifferentiation was quantitated as the percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATII-derived (GFP+) cells that express ATI, but not ATII, cell markers. Using this methodology, we determined the time course and magnitude of transdifferentiation during repair after injury induced by LPS. Moreover, we began to address several important unanswered questions: the rate of ATI cell turnover during homeostasis, the extent to which the alveolar septa are denuded of ATI cells during injury, the relative timing of ATII cell proliferation and transdifferentiation during repair after lung injury, the sequence and rapidity of changes in gene expression and cell morphology during transdifferentiation, and the correlation between transdifferentiation and barrier restoration in the LPS model. In the future, this method of rigorously and quantitatively measuring transdifferentiation can be applied to investigate underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

SPCCreERT2+/−;mTmG+/− mice were treated with tamoxifen, which yielded a recombination efficiency of 94.55% (SD, 2.93%), followed by LPS or HCl. Lung sections were stained for prosurfactant protein (SP) C, T1α, GFP, receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE), aquaporin (AQP) 5, SPA or SPD. Systematic, uniform, random sampling was performed at every level (27, 31).

The surface area of alveolar septa covered by GFP+ proSPC+ (ATII) cells or GFP+ proSPC− T1α+ (ATII-derived ATI) cells and the total alveolar septal surface area were determined by intersection with linear probes (27, 31). The surface density (Ŝv), or surface area per volume, of the structure of interest was determined. The Ŝv of the cells of interest was divided by the Ŝv of the total septal surface to yield the percent of septal surface area covered by the cells of interest.

Complete methods are available in the online supplement.

Results

Alveolar Epithelial Architecture in the Naive Lung

In naive lungs of SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice, ATII cells were cuboidal and expressed GFP+, proSPC+ (Figure 1A), SPA, and SPD (see Figure E1A in the online supplement). ATI cells were squamous, lining both sides of the alveolar septa, and expressed T1α, AQP5, and RAGE and bound tomato lectin (Figures 1A and E1B–E1D). ATII cells covered 1.97 (±0.33)% and ATI cells covered 98.03 (±0.33)% of the alveolar surface area (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Alveolar epithelial architecture in naive lung. Lungs of naive SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice were fixed and immunostained for green fluorescent protein (GFP), T1α, and prosurfactant protein C (proSPC). (A) Open arrowheads indicate cuboidal GFP+ proSPC+ alveolar type (AT) II cells. Solid arrowheads indicate squamous GFP− proSPC− T1α+ ATI cells lining both sides of the alveolar septa (×63 magnification). Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) The percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATI or ATII cells was determined. Solid bar is ATI cells; open bar is ATII cells (n ≥ 5 mice).

Loss of ATI Cells during Lung Injury

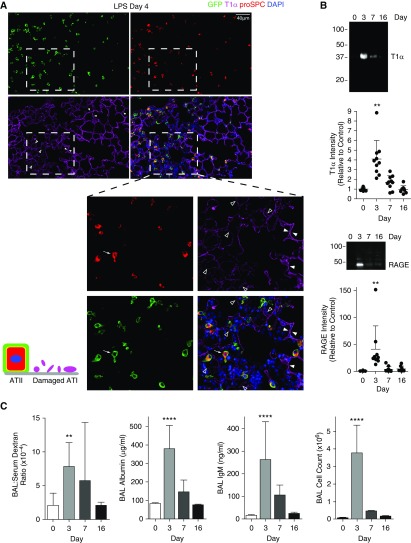

Before examining repair, it was necessary to assess the nature and extent of injury. Surprisingly, despite visual review of thousands of images, we found no areas of alveolar septa completely denuded of ATI cells after LPS or at 18 hours after HCl at a dose above the lethal dose 50 (LD50). We did observe damaged ATI cells, as indicated by dim, speckled T1α staining in areas of intense inflammation, at 4 days after LPS or 18 hours after HCl (open arrowheads in Figures 2A, Figure E2A). This phenomenon was never observed in naive animals, and does not appear to be an artifact due to damaged or out-of-focus tissue (Figure E2B). Of note, ATI cell injury was demonstrably patchy in nature, with large neighboring areas of uninjured lung (solid arrowheads in Figure 2A, Figure E2). To determine whether this ATI cell damage included sloughing of cell fragments, we ultracentrifuged the bronchoalveolar lavage and immunoblotted the pellet for apical (T1α) and basolateral (RAGE) ATI cell markers (detectable ATI cell markers in the bronchoalveolar lavage sediment have previously been shown to correlate with ATI cell loss by electron microscopy [EM] [38]). As shown in Figure 2B and Reference 39, there was substantial ATI cell sloughing in both models (39). The ATI cell damage temporally correlated with epithelial permeability, as measured by leak of 70-kD dextran injected intravenously or endogenous albumin or IgM from the bloodstream into the airspaces (Figure 2C) (39). Importantly, this injury was followed by repair, as indicated by barrier restitution (Figure 2C), thereby providing an important physiological endpoint to correlate with stereological assessment of regeneration of the ATI cell monolayer.

Figure 2.

Patchy ATI cell damage and epithelial permeability without complete denudation during lung injury. (A) SPCCreERT2;mTmG or (B) C57BL/6 mice were treated with intratracheal LPS and killed at the indicated time points. (A) Lung sections were immunostained with antibodies against GFP, T1α, and proSPC. Patchy areas of ATI cell damage without complete denudation of the alveolar septa are observed. Dashed inset: solid arrowheads indicate intact ATI cells, as assessed by bright, crisp T1α staining. Open arrowheads indicate damaged ATI cells, as assessed by dim, speckled T1α staining. Arrow indicates ATII cell with a partially spread morphology. Inflammation and septal thickening are also noted in the areas of ATI cell injury (×20–40 magnification). (B) Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 hours, and the pellet was subjected to Western blotting for T1α and RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation endproducts). Sloughing of ATI cells off the septal surface was determined by detection of T1α and RAGE in the BAL sediment. Densitometry was performed. (C) Epithelial permeability to 70-kD rhodamine B-dextran or endogenous albumin or IgM and BAL cell counts are shown (n ≥ 8 mice/group). Error bars represent SD. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 compared with Day 0.

Transdifferentiation during Repair after Lung Injury

In the LPS model, ATII cells function as the primary progenitor, as demonstrated by a stable percentage of proSPC+ cells that express GFP at Day 27 (data not shown). By 16 days after injury, ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells line both sides of the alveolar septa (Figure 3A). The nascent ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI cells have also lost SPA and SPD expression (Figure E3A) and, in addition to T1α, now express AQP5 and RAGE and bind tomato lectin (solid arrowheads in Figures 3B–3D). Native (GFP−) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells are also observed (arrows in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Transdifferentiation during repair after lung injury quantitated as the percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATII-derived cells expressing ATI, but not ATII, cell markers. SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice were treated with intratracheal LPS and killed at the indicated time points. Lung sections were stained with antibodies against GFP, T1α, RAGE, aquaporin 5 (AQP5), proSPC, and albumin or tomato lectin. (A–D and F) During transdifferentiation, ATII cells spread, down-regulate ATII cell markers, and up-regulate ATI cell markers. Arrowheads indicate squamous ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (proSPC−, T1α+, AQP+, RAGE+, tomato lectin+) cells lining both sides of the alveolar septa. Asterisks indicate cuboidal ATII (GFP+ proSPC+) cells. Arrows indicate native (GFP−) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells (×63 magnification). (E) The percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells was determined (n ≥ 5 mice/group). Error bars represent SD. **P < 0.01. (F) Representative image showing extent of alveolar surface re-epithelialized by ATII-derived ATI cells. Solid arrowheads indicate ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (T1α+) cells. Open arrowheads indicate ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI cells with low T1α expression. Arrows indicate native (GFP−) ATI (T1α+) cells (×40 magnification). (G) Correlation between transdifferentiation and intensity of albumin staining by immunofluorescence. A.U., arbitrary units.

We measured transdifferentiation as the percent of alveolar surface area covered by ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells. The alveolar surface of a naive lung was minimally (0.23%) covered by ATII-derived ATI cells (Figure 3E), which tended to appear in the peripheral lung and likely reflected the transdifferentiation that occurred during homeostatic turnover in the 30 days between tamoxifen administration and killing. During repair after injury, ATII-derived (GFP+) ATI (T1α+ proSPC−) cells covered substantially more alveolar surface area (Figures 3E and 3F). Critically, transdifferentiation temporally correlated with the resolution of epithelial permeability (Figures 2C, 3E, and 3G).

To elucidate the sequence of events that occur as ATII cells transdifferentiate into ATI cells during repair (i.e., whether cell spreading precedes ATI cell marker up-regulation and ATII cell marker down-regulation), we examined GFP+ cells at the time points during which ATII cells are actively transitioning, 4–7 days after injury. Several observations were made. Cuboidal GFP+ cells were always proSPC+ and never T1α+ (Figures 2A and E3B). GFP+ cells with a partially spread morphology that express proSPC, but not T1α, were occasionally encountered (Figures E3B and E3C, arrowheads), although such cells were rare. These cells spread within one alveolus (Figures E3B and E3C, solid arrowhead) or extended pseudopod-like cytoplasmic projections into adjacent alveoli (Figure 2A, arrow, and Figure E3B, open arrowheads). More commonly observed were highly spread (squamous) ATII-derived (GFP+) cells that had lost proSPC but not yet gained T1α expression (Figure E3C, open arrows). Even by 27 days after injury, ATII-derived ATI cells frequently expressed lower levels of T1α (Figure 3F, open arrowheads) than native ATI cells (Figure 3F, arrows). Taken together, these data suggest that, during transdifferentiation, cell spreading precedes down-regulation of ATII and up-regulation of ATI cell gene expression.

Discussion

Transdifferentiation of ATII cells into ATI cells during repair after lung injury is critical for restoration of normal alveolar architecture, barrier integrity, and gas exchange. Landmark studies from the 1970s (2, 6, 13, 14) and recent contemporary lineage tracing studies (15–17) have demonstrated that ATII-to-ATI cell transdifferentiation occurs during repair after lung injury. However, the mechanisms that regulate transdifferentiation have rarely been studied in vivo. A prerequisite for mechanistic investigation is a rigorous, unbiased method to quantitate this process. Our study expands upon previous studies by describing such a method. Using the SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice, we quantitated transdifferentiation as the surface area covered by ATII-derived (GFP+) cells that express ATI, but not ATII, cell markers. SPCCreERT2;mTmG mice can be administered pharmacologic agents to modulate specific signaling pathways or crossed to conditional knockout (floxed) mice, generating mice in which ATII-derived cells are GFP+ and deficient in specific genes of interest. By applying the unbiased stereologic methods described herein to measure transdifferentiation, accurate and reproducible conclusions regarding the underlying mechanisms can be generated.

An essential component of this approach is uniform, random sampling at every level, ensuring that the cells analyzed are representative of the entire population. Representative sampling is a fundamental premise of any statistical analysis, and a requirement for valid and reproducible results (37, 40). Unfortunately, other methods to assess transdifferentiation are subject to bias. Planimetric approaches are limited, because the arbitrarily selected high power fields (HPFs) may not be representative, and differential tissue inflation may skew the data. Flow cytometric analysis may be unreliable, because the yield of ATI cells from lung digestion is extremely low (27, 41) and therefore dubiously representative. Accordingly, scientific journals and societies, including the American Thoracic Society, require that stereology be used for quantitative assessments of cell number and structure (32, 33). Stereologic counting of ATII-derived ATI cells as a method to quantify transdifferentiation would be difficult, because individual ATI cells cannot be readily discriminated by light microscopy using cytoplasmic or membrane markers (Figure 1). Moreover, the current method is preferred, because it incorporates topographical assessment of cell spreading, an integral component of transdifferentiation.

Using this method, we established the time course of transdifferentiation during repair after lung injury in a murine LPS model. ATI cell injury and epithelial permeability peaked at Day 3 (Figure 2). ATII cell proliferation peaked at Day 5 (39). Transdifferentiation occurred from Days 7 to 16. Importantly, as ATII cells spread and transdifferentiated, epithelial barrier integrity was restored (Figures 2C, 3E, and 3G). A correlation between morphologic epithelial injury, as measured by stereology, and permeability, as measured by flux of a tracer, has been demonstrated previously (42–44). We report a similar structure–function relationship during repair: as ATII cells spread to re-epithelialize the alveolar septa, barrier integrity is restored.

In addition, several novel observations were made. During homeostasis, approximately 0.005% of the alveolar surface per day became covered by newly transdifferentiated ATII-derived ATI cells. This physiologic turnover tended to occur in the peripheral lung, as previously reported (15). Moreover, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to query transdifferentiation before proliferation. (Classic autoradiographic studies were inherently unable to detect premitotic transdifferentiation because only replicating cells were labeled [6, 14]). We found that, during repair after lung injury, transdifferentiation occurred mainly after proliferation, in contrast to other epithelia in which cells spread before proliferation during wound healing (45). In addition, despite examination of thousands of high-power fields, cells with characteristics intermediate between ATII and ATI cells were rarely observed. This finding, consistent with previous reports (2, 6, 13, 46, 47), suggests that the spreading and gene expression changes that occur during transdifferentiation are rapid and highly synchronized.

The rare intermediates that were observed were spread T1α− cells (Figure E3C). Moreover, T1α expression, as determined by staining intensity, was often low in the squamous ATII-derived cells (Figure 3F). proSPC− or T1α+ cuboidal cells and proSPC+ squamous cells were never observed. Some previous studies also suggested that spread intermediates retain ATII cell characteristics, with ATI cell characteristics appearing only in highly squamous cells (2, 5, 8, 46, 48). That T1α is expressed subsequent to cell spreading suggests that it is not a critical driver of spreading during re-epithelialization after lung injury, despite its critical role in the development of squamous ATI cells during alveologenesis (49) and the maintenance of foot process morphology in kidney podocytes (50). Still, our findings are consistent with the observation that keratinocyte-specific T1α knockout does not impair cell motility during re-epithelialization of skin wounds (51). The rare intermediate cells captured also appeared to extend cytoplasmic projections within a single alveolus and into neighboring alveoli (Figure 2A, Figure E3B), consistent with the notion that a single ATII progenitor can repopulate ATI cells in multiple adjacent alveoli (15). Presumably, transdifferentiating ATII cells ultimately assume the morphology of native ATI cells, extending cytoplasmic sheets from a central stalk into adjacent alveoli (1).

Contrary to our original hypothesis, we never observed alveolar septa completely denuded of ATI cells. Instead, dim, speckled T1α staining was observed at the peak of injury (Figure 2A), accompanied by epithelial permeability (Figure 2C) and ATI cell sloughing (Figure 2B). Previous EM studies of a variety of types of lung injury revealed a spectrum of ATI cell damage, including cytoplasmic swelling and electron lucency, blebbing, and membrane fragmentation, with the basement membrane remaining mostly covered by necrotic ATI cell debris (2, 6–8, 13, 42, 48, 52, 53). We postulate that, in the LPS model at Day 4 and the HCl model at 18 hours, this spectrum of damage appears as dim, speckled T1α staining by light microscopy. The observation that at no point is the alveolar surface completely denuded of ATI cells suggests that removal of damaged native ATI (GFP− T1α+) cells and spreading of nascent ATII-derived ATI (GFP+ T1α+) cells are highly synchronized in the LPS model. Perhaps the ATII-derived cell spreads under the damaged native ATI cell, physically lifting it off the basement membrane (13, 46). That damaged ATI cells remain on the alveolar surface until the repairing ATII cells transdifferentiate also implies that injured ATI cells may be a source of a signal for transdifferentiation.

At the end of repair, ATII-derived ATI (GFP+ T1α+) cells had re-epithelialized approximately 3% of the total alveolar surface (Figure 3E). A limitation of our study is the inability to quantify injury stereologically. Because the diminished T1α staining intensity by immunofluorescence was incremental, rather than dichotomous, accurate quantification of injured ATI cells was not believed to be possible (48). Previous stereological quantification of the extent of epithelial injury required EM (42–44). We speculate that the focal areas of ATI cell injury (Figure 2A and Figure E2) similarly constituted approximately 3% of the alveolar surface area. In the LPS model, ATII cells do not derive from unlabeled progenitors, as demonstrated by a stable percentage of proSPC+ cells that express GFP, and we assume that nascent ATI cells do not either. Because higher doses of LPS result in animal mortality (data not shown), we speculate that loss of more than 3% of the epithelium may not be compatible with survival, due to considerable physiologic consequences (Figure 2C). Of note, patchy injury is also observed in human acute respiratory distress syndrome (9), particularly in patients who survive. Measuring transdifferentiation only in “injured” areas (32, 42, 54) would increase its apparent magnitude, but may introduce bias depending on how these areas are identified. Regardless, although 3% may seem low, it represents a 21-fold increase over the naive lung (Figure 3E), and this method will be a robust approach to assess mechanisms of transdifferentiation.

We chose the LPS model, because our goal was to study physiologic re-epithelialization by native ATII cells. More severe injury models tend to cause substantial ATII cell death with mobilization of alternate epithelial progenitors, and often result in fibrosis (16, 17, 19, 20). These models may also result in more extensive injury and complete denudation of the alveolar septa, accompanied by an increased magnitude and altered time course of repair. Thus, it is important to note that the specific findings presented here may be limited to the LPS model. However, the methodology described can be readily applied to study re-epithelialization by ATII cells in any lung injury model. Moreover, using mice in which Cre recombinase is driven by another promoter (e.g., Scgb1a1CreER [17]), it could be applied to study re-epithelialization of the alveolar surface with ATI cells derived from other progenitors.

In conclusion, although it has long been recognized that ATII cells transdifferentiate into ATI cells during repair after lung injury, the molecular signals that regulate transdifferentiation have been difficult to study in vivo. A prerequisite for any mechanistic study is a rigorous, unbiased method of quantitation. We present a stereological approach with unbiased sampling and stringent morphometric analysis to quantitate transdifferentiation. We hope that this method will emerge as the standard in the field for future in vivo investigations of the mechanisms underlying transdifferentiation. Transdifferentiation has critical physiologic consequences, as it results in re-epithelialization of the denuded alveolar surface, thus restoring barrier integrity, with a cell that permits efficient gas exchange by virtue of its squamous morphology. Identification of the signaling pathways regulating transdifferentiation may reveal novel therapeutic targets to accelerate physiologic repair and prevent fibrosis after lung injury, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rachel Friedman, Robert Mason, Elizabeth Redente, David Riches, and Irina Petrache (National Jewish Health, Denver, CO, and University of Colorado, Aurora, CO), Michael Matthay (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA), Brian Graham (University of Colorado, Aurora, CO), and Frank Ventimiglia (University of California Davis, Davis, CA) for thoughtful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health K08HL103772, R01HL131608 (R.L.Z.), P01HL014985, R24HL123767 (R.M.T.), and R01HL114381 (P.M.H.), the American Heart Association (R.L.Z.), the Boettcher Foundation (R.L.Z.), and the University of Colorado Denver, Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Career Scholar Award (R.L.Z.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design—R.L.Z., P.M.H., R.M.T., and D.M.H.; analysis and interpretation of data—N.L.J., J.M., and R.L.Z.; acquisition of data—N.L.J., J.M., and R.L.Z.; drafting and revising manuscript—R.L.Z., P.M.H., R.M.T., and D.M.H.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0037MA on June 6, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Weibel ER. On the tricks alveolar epithelial cells play to make a good lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:504–513. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1663OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapanci Y, Weibel ER, Kaplan HP, Robinson FR. Pathogenesis and reversibility of the pulmonary lesions of oxygen toxicity in monkeys. II. Ultrastructural and morphometric studies. Lab Invest. 1969;20:101–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasper M, Haroske G. Alterations in the alveolar epithelium after injury leading to pulmonary fibrosis. Histol Histopathol. 1996;11:463–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller BE, Hook GE. Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of alveolar type II cells in response to silica and other pulmonary toxicants. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;85:15–23. doi: 10.1289/ehp.85-1568321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg GR, Tyrrell C, McKechnie SR, Beers MF, Harrison D, McElroy MC. Coexpression of RTI40 with alveolar epithelial type II cell proteins in lungs following injury: identification of alveolar intermediate cell types. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L382–L390. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00476.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamson IY, Bowden DH. The type 2 cell as progenitor of alveolar epithelial regeneration: a cytodynamic study in mice after exposure to oxygen. Lab Invest. 1974;30:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Alterations of the gas exchange apparatus in adult respiratory insufficiency associated with septicemia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;116:589–615. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirai KI, Witschi H, Côté MG. Electron microscopy of butylated hydroxytoluene–induced lung damage in mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 1977;27:295–308. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(77)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthay MA, Wiener-Kronish JP. Intact epithelial barrier function is critical for the resolution of alveolar edema in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1250–1257. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1376–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2004035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barkauskas CE, Noble PW. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 7. New insights into the cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C987–C996. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00321.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans MJ, Cabral LJ, Stephens RJ, Freeman G. Renewal of alveolar epithelium in the rat following exposure to NO2. Am J Pathol. 1973;70:175–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans MJ, Cabral LJ, Stephens RJ, Freeman G. Transformation of alveolar type 2 cells to type 1 cells following exposure to NO2. Exp Mol Pathol. 1975;22:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(75)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai TJ, Brownfield DG, Krasnow MA. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature. 2014;507:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Rackley CR, Bowie EJ, Keene DR, Stripp BR, Randell SH, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock JR, Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Xue Y, Harris JR, Liang J, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Multiple stromal populations contribute to pulmonary fibrosis without evidence for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1475–E1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117988108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman HA, Li X, Alexander JP, Brumwell A, Lorizio W, Tan K, Sonnenberg A, Wei Y, Vu TH. Integrin α6β4 identifies an adult distal lung epithelial population with regenerative potential in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2855–2862. doi: 10.1172/JCI57673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, Tan K, Tan V, Liu FC, Looney MR, et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature. 2015;517:621–625. doi: 10.1038/nature14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain R, Barkauskas CE, Takeda N, Bowie EJ, Aghajanian H, Wang Q, Padmanabhan A, Manderfield LJ, Gupta M, Li D, et al. Plasticity of Hopx(+) type I alveolar cells to regenerate type II cells in the lung. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6727. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zemans RL, Briones N, Campbell M, McClendon J, Young SK, Suzuki T, Yang IV, De Langhe S, Reynolds SD, Mason RJ, et al. Neutrophil transmigration triggers repair of the lung epithelium via β-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15990–15995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Sadikot RT, Adami GR, Kalinichenko VV, Pendyala S, Natarajan V, Zhao YY, Malik AB. FoxM1 mediates the progenitor function of type II epithelial cells in repairing alveolar injury induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1473–1484. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanjore H, Degryse AL, Crossno PF, Xu XC, McConaha ME, Jones BR, Polosukhin VV, Bryant AJ, Cheng DS, Newcomb DC, et al. β-catenin in the alveolar epithelium protects from lung fibrosis after intratracheal bleomycin Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013187630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mock JR, Garibaldi BT, Aggarwal NR, Jenkins J, Limjunyawong N, Singer BD, Chau E, Rabold R, Files DC, Sidhaye V, et al. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote lung epithelial proliferation. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1440–1451. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yano T, Mason RJ, Pan T, Deterding RR, Nielsen LD, Shannon JM. KGF regulates pulmonary epithelial proliferation and surfactant protein gene expression in adult rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1146–L1158. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crapo JD, Young SL, Fram EK, Pinkerton KE, Barry BE, Crapo RO. Morphometric characteristics of cells in the alveolar region of mammalian lungs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:S42–S46. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.2P2.S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo JD. Allometric relationships of cell numbers and size in the mammalian lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235–243. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flozak AS, Lam AP, Russell S, Jain M, Peled ON, Sheppard KA, Beri R, Mutlu GM, Budinger GR, Gottardi CJ. β-catenin/T-cell factor signaling is activated during lung injury and promotes the survival and migration of alveolar epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3157–3167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.070326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutze K, Vierkotten S, Milosevic J, Eickelberg O, Königshoff M. Enolase 1 (ENO1) and protein disulfide-isomerase associated 3 (PDIA3) regulate Wnt/β-catenin–driven trans-differentiation of murine alveolar epithelial cells. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:877–890. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rieger ME, Zhou B, Solomon N, Sunohara M, Li C, Nguyen C, Liu Y, Pan JH, Minoo P, Crandall ED, et al. p300/β-catenin interactions regulate adult progenitor cell differentiation downstream of WNT5a/protein kinase C (PKC) J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6569–6582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.706416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard CV, Reed MG. Unbiased Stereology. Coleraine, UK: University of Ulster; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER ATS/ERS Joint Task Force on Quantitative Assessment of Lung Structure. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:394–418. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weibel ER, Hsia CC, Ochs M. How much is there really? Why stereology is essential in lung morphometry. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2007:459–467. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00808.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505:612–613. doi: 10.1038/505612a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNutt M. Journals unite for reproducibility. Science. 2014;346:679. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature. 2016;533:452–454. doi: 10.1038/533452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landis SC, Amara SG, Asadullah K, Austin CP, Blumenstein R, Bradley EW, Crystal RG, Darnell RB, Ferrante RJ, Fillit H, et al. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature. 2012;490:187–191. doi: 10.1038/nature11556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McElroy MC, Pittet JF, Hashimoto S, Allen L, Wiener-Kronish JP, Dobbs LG. A type I cell–specific protein is a biochemical marker of epithelial injury in a rat model of pneumonia. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L181–L186. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClendon J, Jansing NL, Redente EF, Gandjeva A, Ito Y, Colgan SP, Ahmad A, Riches DWH, Chapman HA, Mason RJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α signaling promotes repair of the alveolar epithelium after acute lung injury Am J Patholonline ahead of print] 12 Jun 2017; DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research. Rigor and Reproducibility. 2016 Aug 18 [updated 2017 Jul 21; accessed 2016 Dec 11]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/reproducibility/index.htm.

- 41.Gonzalez RF, Dobbs LG. Isolation and culture of alveolar epithelial type I and type II cells from rat lungs. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;945:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velazquez M, Weibel ER, Kuhn C, III, Schuster DP. PET evaluation of pulmonary vascular permeability: a structure–function correlation. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1991:2206–2216. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.5.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ochs M, Nenadic I, Fehrenbach A, Albes JM, Wahlers T, Richter J, Fehrenbach H. Ultrastructural alterations in intraalveolar surfactant subtypes after experimental ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:718–724. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9809060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mühlfeld C, Schaefer IM, Becker L, Bussinger C, Vollroth M, Bosch A, Nagib R, Madershahian N, Richter J, Wahlers T, et al. Pre-ischaemic exogenous surfactant reduces pulmonary injury in rat ischaemia/reperfusion. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:625–633. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00024108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faulkner CS, II, Esterly JR. Ultrastructural changes in the alveolar epithelium in response to Freund’s adjuvant. Am J Pathol. 1971;64:559–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Basic pattern of tissue repair in human lungs following unspecific injury. Chest. 1974;65:14S–19S. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.4_supplement.14s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods LW, Wilson DW, Segall HJ. Manipulation of injury and repair of the alveolar epithelium using two pneumotoxicants: 3-methylindole and monocrotaline. Exp Lung Res. 1999;25:165–181. doi: 10.1080/019021499270376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez MI, Millien G, Hinds A, Cao Y, Seldin DC, Williams MC. T1α, a lung type I cell differentiation gene, is required for normal lung cell proliferation and alveolus formation at birth. Dev Biol. 2003;256:61–72. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui K, Breiteneder-Geleff S, Kerjaschki D. Epitope-specific antibodies to the 43-kD glomerular membrane protein podoplanin cause proteinuria and rapid flattening of podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2013–2026. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baars S, Bauer C, Szabowski S, Hartenstein B, Angel P. Epithelial deletion of podoplanin is dispensable for re-epithelialization of skin wounds. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:785–787. doi: 10.1111/exd.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Structural alterations of lung parenchyma in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 1982;3:35–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woods LW, Wilson DW, Schiedt MJ, Giri SN. Structural and biochemical changes in lungs of 3-methylindole–treated rats. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:129–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hyde DM, Henderson TS, Giri SN, Tyler NK, Stovall MY. Effect of murine gamma interferon on the cellular responses to bleomycin in mice. Exp Lung Res. 1988;14:687–704. doi: 10.3109/01902148809087837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]