The authors conclude that single-item measures of pain, fatigue, and QOL can be incorporated into oncology clinical practice with positive implications for patients and physicians without increasing duration of visits or work burden.

Abstract

Purpose:

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as pain, fatigue, and quality of life (QOL) are important for morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer. Systematic approaches to collect and incorporate PROs into clinical practice are still evolving. We set out to determine the impact of PRO assessment on routine clinical practice.

Methods:

Beginning in July 2010, the symptom assessment questionnaire (SAQ) was administered to every patient in a solid tumor oncology practice at an academic center. The SAQ measures pain, fatigue, and QOL, each on a scale of 0 to 10 points. Results were available to providers before each visit in the electronic medical record. Eighteen months after the SAQ was implemented, an online survey was sent to 83 oncology care providers regarding the use of the SAQ and how it affected their clinical practice, including discussion with patients, duration of visits, and work burden.

Results:

A total of 53% of care providers completed the online survey, producing 44 evaluable surveys. Of these, 86% of care providers reported using information from the SAQ; > 90% of care providers indicated the SAQ did not change the length of clinic visits or contribute to increased work burden. A majority of care providers felt that the SAQ had helped or enhanced their practice. Providers endorsed the SAQ for facilitating communication with their patients.

Conclusion:

This study indicates that simple single-item measures of pain, fatigue, and QOL can be incorporated into oncology clinical practice with positive implications for both patients and physicians without increasing duration of visits or work burden.

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments capture the impact of disease and/or treatment on patients' perspectives concerning their daily function.1 PRO data elements not only facilitate communication between patients and clinicians but also convey proven prognostic information.2–4 Specifically, patient-reported pain, fatigue, and overall quality of life (QOL) have been demonstrated to be important regarding morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer.5–9 However, the ideal methods to capture these subjective measures and incorporate them into clinical practice are not universally established.10 Most importantly, the clinical significance of the information that PROs impart in ongoing clinical management is still largely unknown.

The best example of PRO utility in clinical practice is demonstrated by the usefulness of patient-reported pain for physicians' management decisions.11 Charles S. Cleeland pioneered the item that came to be known as the Brief Pain Inventory 25 years ago, assessing pain on a numeric analog scale from 0 to 10. Collection of pain scores has had a profound impact on clinical care outcomes.12,13 Pain scores from 0 to 4 can be considered as mild pain, not needing clinical intervention. A score of 5 to 6 is moderate, whereas scores ≥ 7 are indicative of a clinically urgent situation.14,15 Pain assessments have demonstrated that effective cancer pain management can have a profound impact on clinical care16,17 and are required for accreditation by agencies such as the Joint Commission.

Fatigue is universally recognized as the most prevalent symptom in patients with cancer and may be reflective of the underlying malignant biologic process of malignancy and/or a result of treatment adverse effects.18 Fatigue can profoundly affect treatment compliance and outcomes.19,20 Similar to pain, fatigue has been demonstrated to be measurable by single-item assessments.21 Recent work has indicated that a score ≤ 5 on a scale of 0 to 10 points is prognostic for survival.9

The assessment of QOL in a clinical setting is an attempt to detect physical or psychosocial issues that might affect a patient's life and may be ovelooked during routine appointments.22 QOL is a more abstract, multidimensional concept than pain or fatigue. QOL includes key aspects such as physical, psychological, intellectual/cognitive, social, and spiritual domains.23,24 Multiple studies have suggested that QOL is a powerful prognostic predictor of survival in hematologic and oncologic malignancies.6,25–27 A score ≤ 5 on a scale of 0 to 10 points has been previously validated to indicate clinically deficient QOL.28–30

Although there has been a significant increase in the collection of patient-based measures of health such as QOL and fatigue data in clinical trials, incorporating standardized PRO assessments into daily oncology practice in a way that adds value to the patient remains a challenge.31–35 One of the barriers to using PROs in clinical practice is the perception of increased work burden for the patient and clinician.36 Indeed, prior studies evaluating effectiveness of QOL patient-based measures in routine oncology practice used several lengthy QOL instruments that limited their practical application in an actual practice setting.37,38 Another barrier to using PROs is a lack of clear guidelines on interventions for patients with poor QOL and/or increased fatigue and a lack of data showing that these interventions improve outcomes.39,40

Linear Analog Self Assessment (LASA) items to measure overall QOL, fatigue, and pain on a scale of 0 to 10 have been validated as general measures of global QOL multidimensional constructs in numerous settings,32,33,37,38 including > 40 different clinical research studies at Mayo Clinic. These studies have indicated that the LASA measures of fatigue, pain, and QOL have prognostic implications for patients with cancer. As a result, in July 2010, the Division of Medical Oncology Clinical Practice Committee at Mayo Clinic initiated the implementation of routine QOL, fatigue, and pain data collection using three LASA items before each patient visit. Approximately 18 months after implementation of the questionnaire, a survey was sent to oncology providers in an attempt to summarize and explore the impact of the questionnaire on physician time and patient management.

Methods

Administration of the Symptom Assessment Questionnaire

The Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) consists of three LASA items; patients rate their pain and fatigue on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the worst, and rate their overall QOL on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being the worst (Appendix Fig A1, online only). The three questions were given to patients at the time they checked in for their appointment. They were instructed by the front desk personnel to answer the questions in relation to how they had been feeling over the past week. The patients completed the LASA items in paper-and-pencil format as they were waiting to be roomed for their appointment. When they were roomed, the clinical assistant entered the information into the electronic medical record, identical to the method for recording vital signs.

The completed questionnaire was then provided to the oncology provider (staff oncologist, oncology fellow, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner). No specific instructions on how to use the information provided on the form were given to the providers before implementing the questionnaire into clinical practice. Providers could choose to act on the information on the questionnaire at their discretion. Desk personnel were asked to bring scores > 6 to the attention of providers when patients were roomed.

Evaluation of SAQ Implementation

A brief questionnaire was given to medical oncology staff using an online survey. A standard e-mail script was sent to the 53 physicians and allied health staff in the Division of Medical Oncology requesting their participation in the study. Results were collected anonymously. The goals of the study were as follows:

Assess the impact on clinical practice of including real-time PRO data collection, including changing care plans, consult time, and other aspects of the patient encounter.

Synthesize the ways in which physicians and allied health staff individually incorporate PRO data into clinical practice.

Approval for this analysis was granted by the Mayo Clinic Investigational Review Board. Statistical analysis was primarily descriptive, using percentages and means where appropriate to summarize the scores obtained and the endorsement and implementation of questions. Qualitative analysis of the qualitative data was undertaken independently by the two principal investigators to identify themes and then cross referenced.

Results

The online survey was completed by 44 (53%) of 83 oncology care providers. More than half of respondents were staff physicians (55%); 25% were fellows, and 20% were nurse practitioners or physician assistants.

Usage

The majority of responding providers (86%) reported using the information provided by the SAQ in their practice; 90% of responding providers indicated that they did typically talk to the patient about ratings of pain, fatigue, or QOL, although more than half said they did so only if an abnormal score was observed. Of those who reported not looking at the SAQ, the main reason given was that they did not think it would add to their practice style.

Cut Points

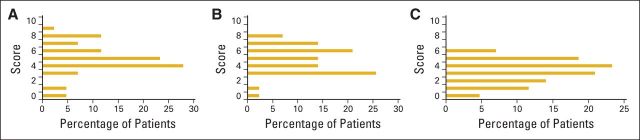

We asked the care providers what cutoff would prompt them to take action (Fig 1). More than 80% of respondents indicated that a score ≥ 4 would cause them to ask about fatigue. However, one of every three respondents indicated that the fatigue score would have to be at least 6 for them to inquire. Pain cut points were substantially lower than those for fatigue. Even a mild score for pain (ie, 0 to 4) would cause 75% of care providers to ask patients about their pain. Results for QOL were similar to those for pain scores. More than 93% of care providers indicated that a QOL score < 8 would cause them to inquire about patient QOL.

Figure 1.

Cut points for (A) fatigue, (B) quality of life, and (C) pain: numbers that trigger clinicians to inquire about each patient-reported outcome.

Practice Implications

More than 90% of the responding care providers indicated that the SAQ did not change the length of clinic visits, nor did it add more work. More than 56% of care providers indicated that the SAQ had helped or enhanced their practice; a further 22% were unsure. Similar levels of endorsement were given regarding the care provider's opinion that the SAQ benefited patients.

The survey included an opportunity for clinicians to provide actions that they took when patients had decreased QOL or increased pain or fatigue. Responses are summarized in Table 1. As expected, adjustments in pain medication, referral to pain clinic, and expansion of history/examination to evaluate the source of increased pain were common actions for poorly controlled pain.

Table 1.

Interventions for Abnormalities in PRO Scores for Fatigue, QOL, and Pain

| Reported Action or Intervention |

|---|

| Elevated fatigue (33 responses, 11 skipped) |

| Recommend exercise |

| Evaluate patient's nutrition status |

| Re-evaluate chemotherapy regimen |

| Consider dose reduction |

| Consider delay in treatment |

| Consider stopping treatment |

| Pharmacologic intervention |

| Antidepressants |

| Dexamethasone |

| Methylphenidate |

| Review medications |

| Expand history to assess for causes of fatigue |

| Assess sleep hygiene (or sleep apnea) |

| Assess for depression |

| Review laboratory results |

| Hemoglobin to assess need for RBC transfusion |

| Relaxation techniques |

| QOL deficits (32 responses, 12 skipped) |

| Re-evaluate chemotherapy regimen |

| Consider dose reduction |

| Consider delay in treatment |

| Consider new regimen |

| Consider stopping treatment |

| Expand history to assess for causes of decreased QOL |

| Assess for depression |

| Assess for anxiety |

| Assess how patient is coping with diagnosis |

| Review social support |

| Assess for social stressors |

| Assess level of pain |

| Assess level of fatigue |

| Re-evaluate goals of care |

| Life goals assessment |

| Referral to complementary/alternative medicine clinic |

| Referral to palliative care service |

| Discuss hospice care |

| High pain levels (35 responses, nine skipped) |

| Adjust/increase pain medications |

| Referral to pain clinic |

| Expand history to assess for causes |

| Assess for depression |

| Assess for anxiety |

| Assess/image for new areas of pain |

Abbreviations: PRO, patient-reported outcome; QOL, quality of life.

Among patients with low QOL, providers assessed the impact of treatment on patient QOL by considering dose reductions or delays in the current treatment regimen, changing the regimen, or discontinuing treatment altogether. Poor QOL also led clinicians to broaden their questioning to assess what psychosocial issues may be contributing. Use of other services including complementary/alternative medicine clinic, palliative care, or hospice was also a response to QOL deficits.

A broad range of action items were given in response to elevated levels of fatigue. These included exercise and relaxation recommendations, nutrition evaluations, pharmacologic interventions, and laboratory evaluations. For some providers, high fatigue led to re-evaluation of the current treatment regimen. Providers also considered dose reductions, treatment delays, and cessation of treatment in response to elevated fatigue.

Qualitative Data Summary

Roughly one third of the care providers added qualitative commentary. Common threads raised were as follows:

The SAQ facilitated communication between them and their patients.

“I think they are helpful, and often stimulate important discussions on how the patients are really doing. I think it's a good springboard to discuss bigger problems.” “Many patients seem to be more ‘open’ and more ready to admit to poor pain control, quality of life or fatigue.”

The SAQ identified problems that otherwise would have likely gone unnoticed.

“Knowing these scores before entering the room allows me to prepare myself mentally for the encounter and to establish goals for the encounter that I may not have had without this information.”

The actual score on each item was sometimes not as important as the change in the score over time.

“I typically don't base decisions on the actual number, but how the number has changed for them over time.”

The study also highlighted that the clinical pathways care providers should take were not always clear.

“I am still struggling with exactly how to use the scores; they seem most helpful when an unexpected score comes up, or when one comes up that seems discordant with patient appearance.”

Clinical Examples

Since initiating the SAQ, we have received multiple reports of how a simple LASA item can identify issues that may not otherwise have been recognized. The following are examples of case reports from clinicians:

An 8-year lymphoma survivor was seen at his annual visit and rated his QOL as 2 on a 10-point scale. When questioned about his score, he admitted to insomnia and suicidal ideations. He was referred to psychiatry, and an antidepressant medication was initiated. One month later, he rated his QOL as 7.

A 60-year-old patient with a history of colorectal cancer returned for an office visit 3 months after completing adjuvant therapy. Laboratory studies, imaging, and examination suggested no evidence of recurrent disease. However, the patient reported his QOL to be 0. When questioned about his poor QOL, the patient admitted to erectile dysfunction. Treatment for erectile dysfunction was initiated, and his QOL improved to 8.

A 57-year-old patient with colorectal cancer returned to clinic for a toxicity check before the next cycle of combination fluorouracil and irinotecan. Although laboratory studies and examination were normal, the patient reported a fatigue score of 8. Dose modifications were made to the patient's chemotherapy regimen, and the fatigue score improved to 2 (on a 10-point scale).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that simple, single-item measures of pain, fatigue, and QOL can be incorporated into oncology clinical practice with positive implications for improving the patient-physician encounter. Oncology physicians and allied health staff strongly endorsed the use of these simple QOL measures, indicating that clinician acceptance and use of PRO measures are not necessarily barriers to PRO data collection in routine clinical practice, as they have been perceived.41 Clinicians reported that these items allowed them to go into the clinical interaction with the patient more prepared, facilitated decision making, and established additional patient care goals. Although the actual lengths of the clinic visits were not timed in this study, most clinicians did not perceive that these items made the visits longer or created more work.

Our study is consistent with other studies demonstrating that adding QOL-related PROs into oncology clinical practice raises awareness of patient functioning and facilitates communication without prolonging encounters.11,42–44 In 2004, Velikova et al43 reported the results of a randomized clinical trial involving the collection of health-related QOL (HRQOL) information using touch-screen technology. (This study used the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Core Quality of Life Questionnaire [version 3.0] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.) A total of 286 patients with cancer were randomly assigned to: (1) an intervention group, in which HRQOL data were collected and feedback provided to clinicians; (2) an attention-control group, in which HRQOL data were collected but no feedback given to physicians; or (3), a control group, in which no HRQOL data were collected. Patients in the intervention and attention-control groups had significantly better HRQOL, and patients in the intervention group had significantly better emotional well-being. Patients in the intervention group had more frequent discussions of symptoms, which did not prolong visits.

Our study was limited by a small sample size of 44 clinicians comprising various levels of training, including staff oncologists, oncology nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and fellows. Although results from this single-institution study do not guarantee generalizability to other institutions or community practices, the LASA items have been successfully used in a broad spectrum of patient settings for clinical research, including community-based practices.45,46 Measures such as the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale have also been used in clinical practices.47–49 Encouraging results from research by Velikova et al,44 for example, indicate the potential broad acceptability of PRO assessment in clinical practice.

We recognize that the LASA items addressing fatigue and QOL do not address the specific domains that contribute to the overall measures. For example, fatigue may be a result of disturbed sleep, pain, lack of appetite, nausea, or insomnia, which could be elucidated by a more detailed questionnaire. However, it should also be recognized that a number of studies have indicated a comprehensive review of systems via multiple PRO domains is impractical in a modern oncology practice.50 Our intention with the SAQ was to keep it simple: use the SAQ as a triage measure, and if a problem is identified, the clinician can probe further with questioning to determine the appropriate intervention.

Regardless of the specific PRO data collection tool used, there is clear evidence that assessing PROs provides benefits to patients in terms of patient-clinician communication, detection of psychological concerns, and overall well-being.42,43 Assessment of PROs provides a window of opportunity for patients to express functional issues, such as emotional distress, or family or sexuality issues that they may not otherwise feel comfortable raising with their provider.36 Addressing PRO concerns acknowledges concern for issues important to patients beyond the status of their cancer and treatment toxicities.

The next logical step is to develop and institute specific clinical pathways to guide clinicians in the management of patients with increased pain, poor QOL, and elevated fatigue. The feedback from clinicians in this study provided a number of potential interventions to address problems identified during PRO screening. These interventions could be incorporated into a tool such as an electronic automated decision tree incorporating more situation-specific questionnaires, which may enhance the assessment of the individual patient.33,36 Web-based guidelines may serve as a basis, but our clinical trials experience has indicated that these need to be supplemented with more specific clinical pathways.40

In conclusion, within the scope limitations of our study, it seems that the collection of PRO data can be incorporated into clinical practice without a perceived increased work burden for providers. PRO questionnaires have the potential to increase communication regarding how patients are functioning in their daily lives, beyond the specifics of disease and treatment. Future research will establish specific pathways to probe further into issues raised by PRO screening. Until then, simple questioning may identify underlying issues for which there are useful interventions to be considered in patient management.

Acknowledgment

Supported by the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities through Grant No. UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health. Presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology International Symposium on Supportive Care in Cancer, Berlin, Germany, June 27-29, 2013.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Joleen M. Hubbard, Jeff A. Sloan

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Velikova G Keding A Harley C, etal: Patients report improvements in continuity of care when quality of life assessments are used routinely in oncology practice: Secondary outcomes of a randomised controlled trial Eur J Cancer 46:2381–2388,2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly CM Bruner DW Mitchell SA, etal: A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment Support Care Cancer 21:1525–1550,2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower JE: Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors J Clin Oncol 26:768–777,2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt Z Wagner LI Beaumont JL, etal: Longitudinal screening and management of fatigue, pain, and emotional distress associated with cancer therapy Support Care Cancer 16:151–159,2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eton DT Fairclough DL Cella D, etal: Early change in patient-reported health during lung cancer chemotherapy predicts clinical outcomes beyond those predicted by baseline report: Results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study 5592 J Clin Oncol 21:1536–1543,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotay CC Kawamoto CT Bottomley A, etal: The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials J Clin Oncol 26:1355–1363,2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maione P Perrone F Gallo C, etal: Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: A prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study J Clin Oncol 23:6865–6872,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montazeri A: Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: An overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008 Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:102,2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloan JA Zhao X Novotny PJ, etal: Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and non–small-cell lung cancer survival J Clin Oncol 30:1498–1504,2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brundage M Blazeby J Revicki D, etal: Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: Development of ISOQOL reporting standards Qual Life Res 22:1161–1175,2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin RH Turk DC Katz NP, etal: Evidence-based clinical trial design for chronic pain pharmacotherapy: A blueprint for ACTION Pain 152:S107–S115,2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turk DC Dworkin RH Burke LB, etal: Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations Pain 125:208–215,2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin RH Turk DC Peirce-Sandner S, etal: Considerations for improving assay sensitivity in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations Pain 153:1148–1158,2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serlin RC Mendoza TR Nakamura Y, etal: When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function Pain 61:277–284,1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li KK Harris K Hadi S, etal: What should be the optimal cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain? J Palliat Med 10:1338–1346,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miaskowski C Dodd MJ West C, etal: Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: A significant barrier to effective cancer pain management J Clin Oncol 19:4275–4279,2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miaskowski C Dodd M West C, etal: Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management J Clin Oncol 22:1713–1720,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barsevick AM Cleeland CS Manning DC, etal: ASCPRO recommendations for the assessment of fatigue as an outcome in clinical trials J Pain Symptom Manage 39:1086–1099,2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curt GA Breitbart W Cella D, etal: Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: New findings from the Fatigue Coalition Oncologist 5:353–360,2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton J Butler L Wagenaar H, etal: The impact and management of cancer-related fatigue on patients and families Can Oncol Nurs J 11:192–198,2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella D, Lai JS, Stone A: Self-reported fatigue: One dimension or more? Lessons from the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT-F) questionnaire Support Care Cancer 19:1441–1450,2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganz PA Kwan L Stanton AL, etal: Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: First results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial J Natl Cancer Inst 96:376–387,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ: Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties ANS Adv Nurs Sci 8:15–24,1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montazeri A: Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007 J Exp Clin Cancer Res 27:32,2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efficace F Therasse P Piccart MJ, etal: Health-related quality of life parameters as prognostic factors in a nonmetastatic breast cancer population: An international multicenter study J Clin Oncol 22:3381–3388,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganz PA, Lee JJ, Siau J: Quality of life assessment: An independent prognostic variable for survival in lung cancer Cancer 67:3131–3135,1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jerkeman M Kaasa S Hjermstad M, etal: Health-related quality of life and its potential prognostic implications in patients with aggressive lymphoma: A Nordic Lymphoma Group Trial Med Oncol 18:85–94,2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huschka MM Mandrekar SJ Schaefer PL, etal: A pooled analysis of quality of life measures and adverse events data in north central cancer treatment group lung cancer clinical trials Cancer 109:787–795,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locke DE Decker PA Sloan JA, etal: Validation of single-item linear analog scale assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients J Pain Symptom Manage 34:628–638,2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sloan JA Berk L Roscoe J, etal: Integrating patient-reported outcomes into cancer symptom management clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute–sponsored clinical trials networks J Clin Oncol 25:5070–5077,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aaronson NK: Quality of life: What is it? How should it be measured? Oncology (Williston Park) 2:69–76,1988 64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine MN, Ganz PA: Beyond the development of quality-of-life instruments: Where do we go from here? J Clin Oncol 20:2215–2216,2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osoba D: A taxonomy of the uses of health-related quality-of-life instruments in cancer care and the clinical meaningfulness of the results Med Care 40:III31–III38,2002suppl [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Till JE Osoba D Pater JL, etal: Research on health-related quality of life: Dissemination into practical applications Qual Life Res 3:279–283,1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao M Karnell LH Funk GF, etal: Health-related quality-of-life outcomes following IMRT versus conventional radiotherapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69:1354–1360,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velikova G Awad N Coles-Gale R, etal: The clinical value of quality of life assessment in oncology practice-a qualitative study of patient and physician views Psychooncology 17:690–698,2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenhalgh J Long AF Brettle AJ, etal: Reviewing and selecting outcome measures for use in routine practice J Eval Clin Pract 4:339–350,1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenhalgh J, Meadows K: The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: A literature review J Eval Clin Pract 5:401–416,1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frost MH Bonomi AE Cappelleri JC, etal: Applying quality-of-life data formally and systematically into clinical practice Mayo Clin Proc 82:1214–1228,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder CF Aaronson NK Choucair AK, etal: Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations Qual Life Res 21:1305–1314,2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ: Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: Challenges and opportunities Qual Life Res 18:99–107,2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Detmar SB Muller MJ Schornagel JH, etal: Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: A randomized controlled trial JAMA 288:3027–3034,2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velikova G Booth L Smith AB, etal: Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial J Clin Oncol 22:714–724,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velikova G Keding A Harley C, etal: Patients report improvements in continuity of care when quality of life assessments are used routinely in oncology practice: Secondary outcomes of a randomised controlled trial Eur J Cancer 46:2381–2388,2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchanan DR White JD O'Mara AM, etal: Research-design issues in cancer-symptom-management trials using complementary and alternative medicine: Lessons from the National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program experience J Clin Oncol 23:6682–6689,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchanan DR O'Mara AM Kelaghan JW, etal: Quality-of-life assessment in the symptom management trials of the National Cancer Institute–supported Community Clinical Oncology Program J Clin Oncol 23:591–598,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk CL, Beaumont C: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, a proposed tool for distress screening in cancer patients: Development and refinement Psychooncology 21:977–985,2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones D Zhao F Fisch MJ, etal: The validity and utility of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory in patients with prostate cancer: Evidence from the symptom outcomes and practice patterns (SOAPP) data from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Clin Genitourin Cancer 12:41–49,2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloan JA Cella D Frost MH, etal: Quality of life III: Translating the science of quality-of-life assessment into clinical practice-an example-driven approach for practicing clinicians and clinical researchers Clin Ther 25:D1–D5,2003suppl D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cleeland CS Sloan JA Cella D, etal: Recommendations for including multiple symptoms as endpoints in cancer clinical trials: A report from the ASCPRO (Assessing the Symptoms of Cancer Using Patient-Reported Outcomes) Multisymptom Task Force Cancer 119:411–420,2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]