The authors' analysis suggests that hematologic oncologists need better clinical markers of when to initiate end-of-life care.

Abstract

Purpose:

Hematologic cancers are associated with aggressive cancer-directed care near death and underuse of hospice and palliative care services. We sought to explore hematologic oncologists' perspectives and decision-making processes regarding end-of-life (EOL) care.

Methods:

Between September 2013 and January 2014, 20 hematologic oncologists from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center participated in four focus groups regarding EOL care for leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Focus groups employed a semistructured format with case vignettes and open-ended questions and were followed by thematic analysis.

Results:

Many participants felt that identifying the EOL phase for patients with hematologic cancers was challenging as a result of the continuing potential for cure with advanced disease and the often rapid pace of decline near death. This difficulty was reported to result in later initiation of EOL care. Barriers to high-quality EOL care were also reported to be multifactorial, including unrealistic expectations from both physicians and patients, long-term patient-physician relationships resulting in difficulty conducting EOL discussions, and inadequacy of existing home-based EOL services. Participants also expressed concern that some EOL quality measures developed for solid tumors may be unacceptable for patients with blood cancers given their unique needs at the EOL (eg, palliative transfusions).

Conclusion:

Our analysis suggests that hematologic oncologists need better clinical markers for when to initiate EOL care. In addition, current quality measures may be inappropriate for identifying overly aggressive care for patients with blood cancers. Further research is needed to develop effective interventions to improve EOL care for this patient population.

Introduction

Although many hematologic malignancies are curable, approximately 35% of affected patients in the United States die of their disease each year.1 The National Quality Forum defines end-of-life (EOL) care as “comprehensive care for life-limiting illness that meets the patient's medical, physical, psychological, spiritual, and social needs.”2(p2) Existing studies regarding improving EOL care have focused predominantly on patients with solid tumors.3–7 Moreover, several quality measures to identify poor EOL care were developed in and for patients with solid malignancies.8,9

It is well-known that blood cancers are associated with aggressive cancer-directed care near death and underuse of palliative care and hospice services.10–16 One study at a comprehensive cancer center demonstrated that only 18% of patients with blood cancers received palliative care services compared with 44% of patients with solid tumors.13 Another study compared performance on National Quality Forum– and American Society of Clinical Oncology–endorsed EOL quality measures for patients with hematologic versus solid cancers.17 Patients with hematologic malignancies had significantly higher rates of emergency room visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and chemotherapy use near the EOL, compared with patients with advanced solid tumors. They were also more likely to die in hospitals and intensive care units.

Although these studies10–17 raise concerns about the quality of EOL care for patients with blood cancers, they provide little insight into the associated perceptions or decision-making processes of the hematologic oncologists involved in their care. In addition, little is known about how to define the EOL phase of disease for these patients. Finally, potential barriers to high-quality EOL care for this group of patients have not been rigorously explored.

In the current study, we sought to characterize hematologic oncologists' perspectives regarding EOL care through a series of focus groups. Specifically, we aimed to determine how physicians identify the EOL phase of disease and to characterize factors that influence initiation of EOL care. We also wished to assess perceptions regarding the acceptability of current EOL quality measures and probe for barriers to delivery of high-quality EOL care.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

Using a purposeful sampling method, we conducted a series of four focus groups at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, a comprehensive cancer center that includes Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Hematologic oncologists were eligible if they had at least 25% clinical effort and provided longitudinal care for adult patients with blood cancers. We held separate sessions for physicians primarily involved in the care of patients with lymphoid malignancies, plasma cell neoplasms, leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, and hematologic malignancies who underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Data Collection

We sent invitations via e-mail to potentially eligible participants describing the purpose of the study and providing a provisional date for the focus group. Physicians were offered $100 incentive for participation. For those who were interested and available, we then confirmed dates and locations for each session. All focus groups were conducted between September 2013 and January 2014. The sessions were comoderated by members of the study team (O.O.O. and G.A.A.). The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Office of Human and Research Studies at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. All participants provided verbal informed consent.

Each session followed a semistructured format including a series of open-ended questions with follow-up probes to elicit hematologic oncologists' perspectives and experiences delivering EOL care (Appendix, online only). We presented hypothetical disease-specific vignettes with stopping points for probes regarding the appropriateness of initiating EOL care. We included hypothetical vignettes because asking physicians about individual practice regarding EOL care is a potentially sensitive topic that can be explored in a less threatening way using this qualitative research technique.18 Participants completed a demographic questionnaire before each session and another questionnaire after each session to capture data regarding perceptions of EOL quality measures. Each session lasted approximately 90 minutes.

Qualitative Data Analysis

All focus group sessions were audiorecorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Thematic analysis was applied to the transcripts given that this technique is best suited for description of perceptions and experiences in qualitative studies.19 One of the moderators (O.O.O.) reviewed all transcripts to verify quality and developed a preliminary coding framework and codebook inductively on the basis of the transcriptions. As recommended by Bernard and Ryan,20 the coding framework was also based on the research question (ie, perspectives of hematologic oncologists regarding defining EOL, initiating EOL care, quality measures, and barriers to high-quality EOL care). Two team members (O.O.O. and D.Y.S.C.) independently coded the data using the codebook that linked themes to defined codes. The process was facilitated by using qualitative software (NVivo 10). Coders wrote reflective notes to describe possible new themes and to clarify definitions of established themes. Intercoder reliability was enhanced through coders comparing coded text across participants and discussing discrepancies with another team member (G.A.A.). The two coders also met to examine emergent themes. Another round of analysis was then conducted using the constant comparative method21 to refine themes by making systematic comparisons across focus groups.

Results

Thirty-nine hematologic oncologists were invited to participate; twenty-five (64%) agreed. Of these, five were ultimately unable to attend their assigned groups as a result of illness or scheduling conflicts that arose after agreeing to participate. Our final sample consisted of twenty hematologic oncologists, including participants from all academic ranks (from fellow to professor). Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Five major themes emerged from the analysis: identifying when EOL begins, factors influencing initiation of EOL care, barriers to quality EOL care, EOL quality measures, and hospice (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants (n = 20)

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 15 | 75 |

| Age, years | ||

| < 40 | 5 | 25 |

| 40-59 | 13 | 65 |

| ≥ 60 | 2 | 10 |

| Academic rank | ||

| Fellow | 1 | 5 |

| Instructor | 6 | 30 |

| Assistant professor | 5 | 25 |

| Associate professor | 5 | 25 |

| Professor | 3 | 15 |

| Time in practice, years | ||

| Median | 13.5 | |

| Range | 2-31 | |

| Primary disease focus | ||

| Leukemia | 6 | 30 |

| Lymphoma | 6 | 30 |

| Myeloma | 4 | 20 |

| HSCT | 4 | 20 |

Abbreviation: HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Identifying When EOL Begins

Participants in all four groups indicated that identifying when the EOL phase of blood cancer begins is challenging. Uncertainty regarding prognostication centered on several factors. First, participants in the leukemia, lymphoma, and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation groups specified that the possibility of cure for many hematologic malignancies, even in relapsed states, makes it difficult to prospectively determine when the EOL phase of disease begins. This was specifically noted as a salient difference between blood cancers and the majority of advanced (stage IV) solid malignancies, which are incurable. As one participant explained, “For metastatic lung cancer, there is no tail on the [survival] curve pretty much. Whereas with lymphoma, although most patients with refractory disease will likely die, we all know there is a tail … through allotransplant.”

Participants agreed that although the median survival for many hematologic malignancies may not differ from advanced solid malignancies, the potential for cure, even when small, impacts their ability to accurately determine when a patient is at the EOL. As one participant noted, “The median survival of older adults with leukemia is not that different from advanced pancreatic cancer or stage IV lung cancer … but we are stuck with this tail and so what do we do with that? We live on the tail, this 5% to 10% tail.” Participants also indicated that even with hematologic malignancies that are incurable at diagnosis (eg, indolent lymphomas and multiple myeloma), the long median survival and the potential to respond to treatment after multiple relapses makes it difficult to know when patients are truly at the EOL.

Many participants reported that the EOL is frequently unpredictable and that the pace of decline near death can be rapid with hematologic malignancies. They reported that the paradigm in the literature of defining EOL as a life expectancy less than 6 months may be difficult to apply to hematologic cancers where changes in a patient's disease status and ensuing death are often sudden and can seldom be prospectively identified months ahead. One participant said, “EOL is such a tricky thing in our field; it can change momentarily. I had a patient who had a transplant, he was doing well, but then he relapsed, the disease took off … and he died within a few days. If you had asked me a month earlier if he was in the EOL phase, I would have said no. He just had a transplant! It's unpredictable.”

Although participants were unable to uniformly define EOL for patients with hematologic malignancies, they were able to identify certain signposts that would alert them to the likelihood that a patient was near or possibly at the EOL. Table 2 lists potential EOL signposts for the different diseases the participants treated. Refractory disease and relapse after transplant were the most commonly reported.

Table 2.

Potential Signposts for the EOL Phase of Disease

| Leukemia | Lymphoma | Myeloma | HSCT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory disease | Refractory disease | Refractory disease | Relapse after transplant |

| Relapse after transplant | Relapse after transplant | Rapid relapse (< 1 year) after transplant | Refractory graft-versus-host disease |

| CNS involvement | CNS involvement | Shorter progression-free intervals in disease course | Lack of engraftment |

| Worsening PS | Worsening PS | Worsening PS | Oxygen-dependent bronchiolitis obliterans |

| Elderly AML with complex karyotype ineligible for transplant | Organ insufficiency |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; EOL, end-of-life; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation; PS, performance status.

Factors Influencing Initiation of EOL Care

Participants identified several factors that influenced the timing of EOL discussions and transition from disease-directed to EOL care. All acknowledged that age was a factor that interacted heavily with the decision of whether to transition to primarily palliative care. The majority of hematologic oncologists in our study described a hesitation to forego aggressive/life-extending approaches with younger patients, even in situations where the likelihood of benefit was slim. “Age plays such a big role; if you've got somebody who is 25 years old, you are going to go down blazing typically for someone like that—they may get multiple transplants, they may get seven or eight lines of chemotherapy because they can take it for a while.”

Another factor identified in all four groups was comorbidity. Physicians were more willing to initiate EOL care in situations in which the perceived burden of comorbidity precluded delivery of effective or potentially curative therapy. Several participants also noted that performance status (PS) is frequently part of their rubric in arriving at a decision to initiate EOL care. They noted that, unlike with most advanced solid malignancies, patients with hematologic malignancies with borderline to poor PS may initially be treated because of the potential for cure. On the other hand, if PS were to consistently decline with disease-directed therapy, physicians were more likely to initiate EOL discussions.

Several participants indicated that if disease-directed therapies were causing a significant worsening of their patients' quality of life (QoL), they would be more likely to initiate discussions about transitioning to EOL care. However, the likelihood of strongly incorporating QoL into the decision to transition to EOL care was weighed against the possibility of cure, with the latter often prioritized. In certain diseases such as multiple myeloma, which is incurable, physicians particularly emphasized the importance of QoL. One participant said, “If QoL is declining because of drug toxicities, cytopenias, or multiple trips to the hospital, I think that's when it's easier to start talking about EOL care.”

Barriers to Quality EOL Care

Several barriers to high-quality EOL care were described by the participants in all groups. Many brought up the issue of unrealistic physician expectations fueled by the fact that there are more lines of active—and potentially curative—therapy for some hematologic malignancies when compared with advanced solid malignancies. As one physician said, “Part of it could be our unrealistic expectations. As providers, these are diseases where there are a lot of active drugs, unlike a lot of advanced solid tumors…. You are always thinking you can pull some rabbit out of the hat; you tend to think that something is going to work.”

Participants also identified unrealistic patient expectations as a barrier to quality EOL care both for potentially curable and incurable hematologic malignancies. One participant noted, “Occasionally, patients do pinch you in a corner. We've all had patients that for whatever reasons insist on care that we may think is futile.” Similarly, some participants indicated that the fact that patients with advanced blood cancers can be treated for so long may make them less likely to agree to transition to EOL care. Participants also noted that the close, visit-intensive, and long-term relationships they often develop with their patients made it difficult to conduct EOL discussions. There was also a recurring concern about how EOL discussions may take away patients' hope and how the unpredictable nature of disease progression for some blood cancers may also be a barrier to initiating EOL care.

EOL Quality Measures

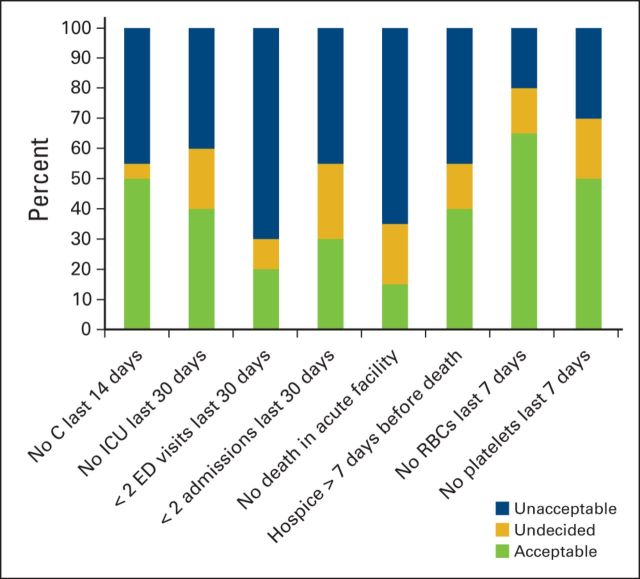

Most hematologic oncologists felt that current quality measures for EOL care10,22,23 were unacceptable for patients with hematologic malignancies (mean acceptability, 32.5%; Figure 1). They were not opposed to measuring the quality of EOL care for patients per se but felt that hematology-specific measures needed to be developed. New potential hematology-specific measures such as no platelet transfusions (50%) or blood transfusions (65%) within the final week of life were more uniformly acceptable than current measures including no death in an acute care facility (15%) and not more than one emergency department visit in the last month of life (20%).

Figure 1.

Acceptability of end-of-life quality measures as rated by participants. C, chemotherapy; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; RBC, red blood cell.

Hospice

Although most participants acknowledged the importance of hospice, many expressed concern that the current hospice model seems largely geared for patients with solid tumors and does not provide essential services for patients with hematologic malignancies. Leukemia physicians also described concerns about patients experiencing fatal bleeding episodes at home and the lack of availability of platelet transfusions in most hospices as a problem, with one participant stating “a patient exsanguinating in front of his family is not very appropriate EOL care.” Some participants raised concerns that enrolling patients in hospice required limiting contact with their patients, which both patients and physicians may resent, especially given that they often see their patients more than once per week as outpatients and daily as inpatients. Participants noted that modifying hospice to better meet the needs of patients with blood cancers could potentially increase utilization rates. As one participant noted, “Right now, the gap between home hospice and acute care hospitals is just too wide for our patients.”

Discussion

We identified several themes that influence EOL decision making for hematologic oncologists. First, the lack of clarity in defining when the EOL period begins for patients with hematologic malignancies evokes uncertainty regarding when to initiate EOL care. Second, barriers to quality EOL care are multifaceted, involving physicians, patients, and the existing health care structure. They include unrealistic patient and physician expectations and the inadequacy of existing home-based EOL care services. Third, we found marked variation in hematologic oncologists' acceptance of current EOL quality indicators; most were endorsed by fewer than 50% of participants. Finally, physicians reported that patients with hematologic malignancies require unique EOL medical care, which is distinct from the needs of patients with solid tumors and poorly addressed in existing hospice models.

Whereas prior studies have established that differences exist in care near the EOL for solid versus hematologic malignancies,10,12,13,15,17,24 our analysis begins to investigate possible factors that account for these differences. Consistent with one prior survey of Australian hematologic oncologists,25 we found that prognostic uncertainty makes it difficult to determine when it is appropriate to transition from curative to EOL care. There are many prognostic tools in hematologic oncology (eg, Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for myelodysplastic syndromes,26 International Prognostic Index for Lymphoma27), but most are scored at diagnosis and are less useful after disease progression. Our data suggest that future studies should examine dynamic prognostic or EOL-specific tools28 to more accurately determine the EOL phase for the hematologic malignancies and enable earlier initiation of appropriate EOL care.

Despite uncertainty regarding when the EOL phase of disease begins, our participants were able to identify signposts during the disease course that would raise the possibility of EOL being near. If these are confirmed through further research, we suggest that EOL discussions be initiated (or readdressed) when such signposts appear, even if the potential for cure still exists. Such conversations would ensure that patients' EOL preferences are known and will increase the likelihood that they receive care that is consistent with their goals.3,5,29

Only a small proportion of hematologic oncologists felt that current EOL quality measures were acceptable for patients with hematologic malignancies. To effectively improve quality of care, such measures must not only be feasible but also acceptable to relevant stakeholders.30 Many of the currently endorsed quality indicators were developed primarily with input from solid tumor stakeholders.8 Our study suggests that input from hematologic oncologists and patients with blood cancers is needed to better understand what defines high- versus low-quality EOL care for these cancers. Indeed, most acceptable to our participants were novel hematology-specific measures aimed at reducing transfusions within the final week of life.

Although hospice is as an essential part of high-quality EOL care, hospice enrollment rates are low among patients with hematologic malignancies.10,14 Our findings suggest that the gap between typical hematologic care (such as platelet transfusions and regular clinic visits) and the services available under the current hospice model may explain why this resource is not used more widely. The requirement that Medicare beneficiaries forgo cancer-directed therapy, including transfusions, to access hospice care likely limits the number of patients with hematologic malignancies that might otherwise benefit from receipt of hospice services.31

Indeed, a pilot study that allowed disease-directed treatment and expanded hospice benefits doubled hospice enrollment and significantly lowered acute and intensive care utilization, even for those with blood cancers.32 Several groups have urged policy makers to redefine the Medicare hospice benefit such that the decision to pursue disease-directed care is not tantamount to sacrificing high-quality EOL care.9,33–35 The recently announced Medicare Care Choices Model project36 to test concurrent care for patients with advanced cancers may address this issue.

Our study has limitations. First, because all of our participants practice in tertiary care centers and provide care only to patients with hematologic malignancies, their perspectives may not be generalizable to hematologic oncologists who practice in community settings and/or provide care to patients with blood cancers as well as patients with solid malignancies. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that 20 hematologic oncologists from three different institutions agreed to discuss their practices regarding EOL care and that the themes identified converged. Second, given our limited sample size, we were unable to assess whether physician characteristics were associated with certain perspectives. Finally, our study may be susceptible to participation bias; however, overall 64% of the physicians approached agreed to participate, and a sizable number of the rest opted out ostensibly only because of scheduling conflicts.

In summary, our analysis suggests that a patient-centered approach that focuses on the specific EOL needs of patients with blood cancer is needed. These potentially include hematology-focused hospice, quality measures that are specific to blood cancers, and the development of dynamic prognostication tools along with other EOL signposts. Such developments will hopefully move us closer to truly providing that comprehensive care that meets the “medical, physical, psychological, spiritual, and social needs” of patients with blood cancer at the EOL.

Acknowledgment

Supported by a Lymphoma Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow Award (O.O.O.).

Appendix

Focus Group Interview Guide

To start off our discussion, I will present a case vignette with some questions to provide a background.

Ms Z is a 65-year-old woman (comorbidity of hypertension) recently diagnosed with stage IIIB diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). She has a high International Prognostic Index of 4, and she presents to you for further management.

What would you do at this point?

Do you think it is reasonable to discuss supportive care now?

Why do you think it is reasonable or unreasonable?

Ms Z chooses to receive treatment with six cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Interim scans after three cycles of treatment show some shrinkage in her lymphadenopathy. At the end of six cycles of treatment, positron emission tomography scans demonstrate residual disease. She meets criteria for primary refractory disease.

What would you do at this point?

Do you think it is reasonable to discuss supportive care now?

Why do you think it is reasonable or unreasonable?

What factors would make you more aggressive about pursuing continued cancer-directed treatment versus less aggressive?

Ms Z undergoes a biopsy that confirms that she has persistent DLBCL. She undergoes salvage chemotherapy with rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide. She achieves a complete remission after completion of two cycles and undergoes high-dose chemotherapy treatment followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation. Nine months after autologous stem-cell transplantation, she presents to you with noticeable cervical lymphadenopathy, weight loss, fatigue, and night sweats. Imaging and biopsy confirm recurrent DLBCL.

What would you do at this point?

Do you think it is reasonable to discuss supportive care now?

Why do you think it is reasonable or unreasonable?

If you discuss supportive care, what influences your decision to do so?

You discuss clinical trial options with the patients. There is a phase II trial for relapsed DLBCL open at your institution. Ms Z is considering enrolling in the trial. Ms Z enrolls in the clinical trial. Unfortunately, her disease progresses rapidly, and she is taken off study. She continues to have rapidly enlarging lymphadenopathy, weight loss, and fatigue. She develops fevers and is admitted to the hospital. She has sepsis and is transferred to the intensive care unit.

What would you do at this point?

Do you think it is reasonable to discuss supportive care now?

Why do you think it is reasonable or unreasonable?

If you discuss supportive care, what is the content of your supportive care discussion?

Do you think the patient's expectations/preferences are related to what you said at earlier stages (eg, presenting versus not presenting supportive care as an option)?

The next series of questions focus on identifying the EOL phase.

How do you determine that a patient is near the end of life?

What factors are important to you in arriving at the decision that a patient is in the end-of-life phase?

Why do you think the factors you mentioned are important?

For patients with solid malignancies, those with metastatic disease and a life-expectancy less than 6 months are usually considered to be in the end-of-life phase; what would you consider a potential definition of the end-of-life phase for the hematologic malignancies?

Next, let us talk about components of end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies.

What is your perspective about what makes up ideal end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies?

How would you define quality end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies?

Are there special considerations regarding end-of-life care that are unique to hematologic malignancies versus solid tumors?

If yes, what are they? Why do you think they are unique?

Now that we have discussed components of end-of-life care and how to determine whether a patient is near the end of life, let us talk about transitioning to end-of-life care.

When you identify whether a patient is near the end of life, what factors influence the decision to transition to end-of-life care versus continuation of tumor-directed care?

Do you encounter challenges in initiating end-of-life care for your patients?

If yes, can you share the challenges you have experienced with us?

In situations in which you have initiated end-of-life care for patients, do you experience challenges in the practical delivery of such care?

If yes, can you share the challenges you have experienced with us?

How can the quality of end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies be improved?

Note: Case vignettes were modified to match the disease focus (lymphoma, multiple myeloma, leukemia, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation) of each session.

Table A1.

Themes Regarding EOL Care for the Hematologic Malignancies

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Identifying when EOL begins | “For metastatic lung cancer, there is no tail on the [survival] curve pretty much. Whereas with lymphoma, although most patients with refractory disease will likely die, we all know there is a tail … through allotransplant.” |

| “The median survival of older adults with leukemia is not that different from advanced pancreatic cancer or stage IV lung cancer … but we are stuck with this tail and so what do we do with that? We live on the tail, this 5% to 10% tail.” | |

| “I think the difference is that you can say to a metastatic lung cancer patient, you are not going to be cured … I don't think you can say so in some of these high-risk [hematologic] patients, you actually can't say that they have no chance of cure” | |

| “I think the thing is predictability. I think if somebody has lung or pancreatic cancer, it is more predictable when the EOL really is. Whereas, I think for our patients, it's just so hard and much more acute.” | |

| “EOL is such a tricky thing in our field; it can change momentarily. I had a patient who had a transplant, he was doing well, but then he relapsed, the disease took off … and he died within a few days. If you had asked me a month earlier if he was in the EOL phase, I would have said no. He just had a transplant! It's unpredictable.” | |

| Factors influencing EOL care initiation | “Age and comorbidity … depending on age, is the patient a transplant candidate? Can they physically tolerate aggressive salvage therapy?” |

| “Age plays such a big role; if you've got somebody who is 25 years old, you are going to go down blazing typically for someone like that—they may get multiple transplants, they may get 7 or 8 lines of chemotherapy because they can take it for a while.” | |

| “There are those who may not even be refractory but are unable to tolerate [treatment] because of comorbidities; that would be when I would seriously have those [EOL] discussions.” | |

| “If quality of life is declining because of drug toxicities, cytopenias, or multiple trips to the hospital, I think that's when it's easier to start talking about EOL care.” | |

| Barriers to quality EOL care | “Part of it could be our unrealistic expectations. As providers, these are diseases where there are a lot of active drugs, unlike a lot of advanced solid tumors.… You are always thinking you can pull some rabbit out of the hat; you tend to think that something is going to work.” |

| “You get invested in your patients. We've known a lot of these patients for a long time, and we've seen them more than their primary care doctor, and you start to have an unrealistic belief in your ability to control the disease.” | |

| “I think it is a lot easier when you get referred a patient who is refractory from somebody else to be able to say we really don't have anything. When it is your own patient, it is a lot more difficult.” | |

| “People are very resistant to giving up [on treatment]; they feel like it is a failure on their part.” | |

| “Occasionally, patients do pinch you in a corner. We've all had patients that for whatever reasons insist on care that we may think is futile.” | |

| “The one thing I don't want to do is completely take away any hope. Because if there's still a chance, there's still some hope, and at least you give them time to think about their options.” | |

| “The window is very small for us to discuss EOL care because a lot of these complications happen acutely, and it's hard to predict.” | |

| EOL quality measures | “I think there is a difference between ICU care that involves aggressive round-the-clock nursing care and blood pressure support with the hope that a patient is going to turn around in 24 to 48 hours versus intubation and resuscitation.” |

| “Patients with heme malignancies are generally completely different from patients with solid tumors. A lot of these measures, like no chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life, I would expect them to be different based on the fact that chemotherapy for heme malignancies is generally more effective than chemotherapy for solid tumors; these parameters—are they applicable to our patient population? | |

| “I don't see any metric that really applies. I think the transfusion thing is a reasonable approach … nobody is going to survive or die based on one transfusion. | |

| “It's hard because these measures are reasonable for relapsed refractory patients, but that's not all of our patients.” | |

| Hospice | “Usually hospice won't take the patient if they need transfusions; a patient exsanguinating in front of his family is not very appropriate EOL care.” |

| “Most of these patients … are too sick to be on hospice; they still have a lot of nursing needs.” | |

| “I think hospice is largely geared for solid tumor patients. I really emphasize in our patients that they need 24-hour day care; hospice does not provide that.” | |

| “If there were certain designated hospices that would accept patients with advanced hematologic malignancies—that would provide maybe once a week platelet or red cell transfusions, something reasonable—that would be the best way to do it.” | |

| “Should certain hospice care models be modulated for heme malignancies to enable us to utilize that resource? The general inpatient hospice criteria for a solid tumor patient—intractable pain not manageable at home, dynamic pain score—all these things can't apply, and so maybe a different metric is needed, because right now the gap between home hospice and acute care hospitals is just too wide for our patients.” | |

| “There should be more leeway for us to use inpatient hospice services. There has to be a little bit more coverage for that because the death for heme malignancies is more acute with the bleeding.” |

Abbreviations: EOL, end-of-life; heme, hematologic; ICU, intensive care unit.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Oreofe O. Odejide, Gregory A. Abel

Administrative support: Gregory A. Abel

Collection and assembly of data: Oreofe O. Odejide, Corey D. Watts, Gregory A. Abel

Data analysis and interpretation: Oreofe O. Odejide, Diana Y. Salas Coronado, Alexi A. Wright, Gregory A. Abel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Siegel R Ma J Zou Z, etal: Cancer statistics, 2014 CA Cancer J Clin 64:9–29,2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus standards: Palliative care and end-of-life care—A consensus report, 2014. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%e2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx.

- 3.Mack JW Weeks JC Wright AA, etal: End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences J Clin Oncol 28:1203–1208,2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA Zhang B Ray A, etal: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment JAMA 300:1665–1673,2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack JW Cronin A Keating NL, etal: Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study J Clin Oncol 30:4387–4395,2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS Greer JA Muzikansky A, etal: Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer N Engl J Med 363:733–742,2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B Wright AA Huskamp HA, etal: Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations Arch Intern Med 169:480–488,2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earle CC Park ER Lai B, etal: Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data J Clin Oncol 21:1133–1138,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earle CC Neville BA Landrum MB, etal: Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life J Clin Oncol 22:315–321,2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earle CC Landrum MB Souza JM, etal: Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol 26:3860–3866,2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho TH Barbera L Saskin R, etal: Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada J Clin Oncol 29:1587–1591,2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadul N Elsayem A Palmer JL, etal: Predictors of access to palliative care services among patients who died at a Comprehensive Cancer Center J Palliat Med 10:1146–1152,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui D Kim SH Kwon JH, etal: Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center Oncologist 17:1574–1580,2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sexauer A Cheng MJ Knight L, etal: Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies J Palliat Med 17:195–199,2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang ST Wu S-C Hung Y-N, etal: Determinants of aggressive end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006 J Clin Oncol 27:4613–4618,2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng WW Willey J Palmer JL, etal: Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center J Palliat Med 8:1025–1032,2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui D Didwaniya N Vidal M, etal: Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: A retrospective cohort study Cancer 120:1572–1578,2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barter C, Renold E: The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research, Social Research Update Social Research Update 1999Surrey, England: University of Surrey [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guest GS, MacQueen KM, Namey EE: Applied Thematic Analysis 2011Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernard HR, Ryan GW: Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches 20091st ed Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeije H: A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews Qual Quantity 36:391–409,2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campion FX Larson LR Kadlubek PJ, etal: Advancing performance measurement in oncology: Quality Oncology Practice Initiative participation and quality outcomes J Oncol Pract 7:31s–5s,2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality Oncology Practice Initiative: The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative quality measures. http://qopi.asco.org/documents/QOPI-Spring-2014-Measures-Summary.pdf.

- 24.Hui D Karuturi MS Tanco KC, etal: Targeted agent use in cancer patients at the end of life J Pain Symptom Manage 46:1–8,2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auret K, Bulsara C, Joske D: Australasian haematologist referral patterns to palliative care: Lack of consensus on when and why Intern Med J 33:566–571,2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg PL Tuechler H Schanz J, etal: Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes Blood 120:2454–2465,2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project N Engl J Med 329:987–994,1993[No authors listed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kripp M Willer A Schmidt C, etal: Patients with malignant hematological disorders treated on a palliative care unit: Prognostic impact of clinical factors Ann Hematol 93:317–325,2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright AA Mack JW Kritek PA, etal: Influence of patients' preferences and treatment site on cancer patients' end-of-life care Cancer 116:4656–4663,2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunfeld E Lethbridge L Dewar R, etal: Towards using administrative databases to measure population-based indicators of quality end-of-life care: Testing the methodology Palliative Medicine 20:769–777,2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furman CD, Doukas DJ, Reichel W: Unlocking the closed door: Arguments for open access hospice Am J Hosp Palliat Care 27:86–90,2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spettell CM Rawlins WS Krakauer R, etal: A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care J Palliat Med 12:827–832,2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiener JM, Tilly J: End-of-life care in the United States: Policy issues and model programs of integrated care Int J Integr Care 3:e24,2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peppercorn JM Smith TJ Helft PR, etal: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer J Clin Oncol 29:755–760,2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright AA, Katz IT: Letting go of the rope: Aggressive treatment, hospice care, and open access N Engl J Med 357:324–327,2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare care choices model. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Medicare-Care-Choices/