Abstract

Background

Glaucoma is classified as a neurodegenerative disease. However, the biomarkers of neurodegeneration in the aqueous humour of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) eyes have not been quantitatively examined yet. In this study, levels of neurodegeneration-related cytokines in the aqueous humour of POAG eyes were measured and compared with those of non-glaucoma (senile cataract) control eyes.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 24 patients (24 eyes) with POAG and 22 patients (22 eyes) with cataract. Aqueous humour samples were collected before the commencement of phacoemulsification surgery. The concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), cathepsin D, myeloperoxidase (MPO), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), soluble neural cell adhesion molecule (sNCAM), soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were measured using the Luminex suspension array technique. The clinical characteristics of the patients were also obtained for correlation analysis.

Results

Compared with the cataract group, the levels of cathepsin D (P < 0.001), sNCAM (P < 0.001) and sVCAM-1 (P = 0.007) were significantly higher in the aqueous humour samples from POAG. The levels of BDNF, sICAM-1, MPO and PAI-1 did not differ among the groups. Mean deviation (MD) values measured by the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer were significantly associated with levels of cathepsin D (P < 0.001; ρ= − 0.668), sICAM-1 (P = 0.003; ρ= − 0.579), sVCAM-1(P < 0.001; ρ= − 0.695), and PAI-1 (P = 0.007; ρ= − 0.533). The cytokines showed a positive correlation among each other (P < 0.0083).

Conclusion

These data suggest that POAG patients had elevated levels of multiple biomarkers of neurodegeneration in the aqueous humour, and these elevated biomarkers may be related to trabecular meshwork injury.

Trial registration

This study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-OOC-16008516) on May 22, 2016.

Keywords: Primary open angle glaucoma, Cataract, Neurodegeneration, Aqueous humour

Background

Glaucoma is a group of optic neuropathy characterized by the degeneration of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons and somas [1]. It is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world, especially among the elderly. With the world population growing and the average lifespan increasing, glaucoma will affect more people. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide will increase to 76.0 million in 2020 and 111.8 million in 2040 [2].

Although glaucoma is defined primarily by optic nerve damage, neurodegeneration extends to the retina, lateral geniculate nucleus, and the occipital cortex [3, 4]. Recent research indicated that glaucoma destroy neurons through oxidative stress, impairment in axonal transport, neuroinflammation, and excitotoxicity [5]. As a neurodegenerative disorder, glaucoma even shares some similarities with other diseases in this category, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS). These similarities include the selective loss of neuron populations, trans-synaptic degeneration in which the disease spreads from injured neurons to connected neurons, and common mechanisms of cell injury and death [6]. Glaucoma morbidity is higher among patients with AD and PD [7]; moreover optic nerves from AD patients are characterized by the loss of RGCs, the earliest dying cell in glaucoma [8].

Glaucoma can often be hard to notice until damage has already occurred [5]. In addition, lowering intraocular pressure (IOP) is currently the only way to delay the advancement of glaucoma. In view of the limitations of glaucoma diagnosis and therapy, some new potential biomarkers need to be found. Several studies have suggested that levels of neurodegeneration-related cytokines are altered in neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, elevated levels of cathepsin D in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was found in AD patients [9], and increased levels of sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1 in CSF was found in MS patients [10, 11]. The levels of these cytokines and possibly other biological factors may prove to be useful biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease.

Aqueous humour (AH) is the product of the ciliary body. It provides nutrition for the iris, cornea, lens, and trabecular meshwork [12]. In addition, it also exhibits anti-inflammatory potential, such as inhibiting neutrophil activation, preventing natural killer cells from lysing targets, suppress nitric oxide production by macrophages, and interfering with complement activation [13]. Altered cytokine levels in the AH have been observed in ocular disease, such as glaucoma [14], macular degeneration [15], and high myopic cataract [16]. Some investigators hypothesize that AH molecular alterations reflect glaucoma pathogenesis: the same events occur in the anterior chamber both at the level of the optic nerve and the central nervous system [17]. Therefore, the analysis of the AH can provide important information regarding the physiological and pathophysiological process in eyes. In POAG, the AH may play an important role in facilitating the migration of cytokines that stimulate the activity of human trabecular meshwork (HTM) cells [17, 18]. In addition, the AH contains several signalling molecules promoting synthesis, degradation, and modification of the extracellular HTM matrix [19]. Therefore, changes in the AH proteome may reflect cellular damage in HTM. However, a study in the literature reported that the neurodegenerative marker in the AH of POAG eyes is not adequate; thus, the present study measured biomarkers of neurodegeneration (BDNF, cathepsin D, sICAM-1, MPO, sNCAM, sVCAM-1, and PAI-1) in the AH from POAG patients.

Methods

Subjects and enrolment criteria

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Daping Hospital of the Third Military Medical University (No._47) and adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. We also registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-OOC-16008516) on May 22, 2016. Each patient recruited in this study was given an explanation about the research and signed an informed consent for AH collection. Participants were recruited between June 2016 and December 2016. All patients were from a Chinese Han population. The axial length of these patients was measured using an IOL Master device (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), and the Mean deviation (MD) values was measured by the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA).

The diagnostic criteria of the POAG group were according to the following: (1) an open iridocorneal angle; (2) the characteristic appearance of glaucomatous optic neuropathy such as enlargement of the optic disc cup or focal thinning of the neuroretinal rim; (3) corresponding visual field defects tested; and (4) no evidence of secondary glaucoma.

The exclusion criteria for all groups included the following: (1) ocular inflammatory disease, systemic inflammatory, autoimmune, or pre-existing ocular disease (diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration and retinal vein/artery occlusion); (2) other neurodegeneration disease (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson disease or multiple sclerosis); (3) previous intraocular surgeries; (4) an AH sample less than 50 μL; (5) and incomplete data. These criteria were in compliance with the International Society for Geographical and Epidemiological Ophthalmology (ISGEO) classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys by Foster et al. [20].

All POAG patients recruited were receiving IOP-lowering medication in the form of monotherapy or a combination of up to four of the following compounds: Brimatoprost, Tafluprost, Latanoprost (prostaglandin derivatives), Timolol (β-blocker), Brimonidine (α2-agonist), Dorzolamide, and Brinzolamide (carbonic anhydrase inhibitors).

Collection of aqueous humour samples

All AH samples were collected under sterile conditions via an anterior chamber paracentesis before the commencement of phacoemulsification surgery. Patients were under general anaesthesia or local anaesthesia. Approximately 50–100 μL of the undiluted AH samples were collected by a single surgeon with a 30-gauge needle. Surgeries were performed between 9:00 am and 12:00 am. The AH samples were frozen and stored at −80 °C within 10 min until further analysis.

Multiple immunoassay analyses

Concentrations of cytokine in AH were detected using multiplex bead-based immunoassays (Luminex, Merck, USA) with Human Neurodegenerative Disease Panel 3 (BDNF, cathepsin D, sICAM-1, MPO, sNCAM, sVCAM-1 and PAI-1). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. [21] Briefly, samples were thawed and centrifuged at 10000 ×g for 5 min to remove precipitates. A 25 μL aliquot of the AH was transferred to a 96 well pre-wet filter plate, and a part of each sample was placed into one of the capture microsphere multiplexes. Sample and capture microspheres were completely mixed and incubated at 4 °C for 18 h (protected from light). After two washes, multiplexed cocktails of biotinylated reporter antibodies were transferred and mixed. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature and two washes, multiplexes were developed using an excess of the solution of streptavidin plus phycoerythrin. The solution was mixed into each multiplex, after which it was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Follow a washing step; a Luminex 200 Instrument (Luminex Corporation, TX, USA) was used for analysis and proprietary data analysis software (MILLIPLEX Analyst. Vision 5.1) was used for interpretation of the data.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by using the SPSS for Windows, Version 17.0 (IBM-SPSS, Chicago, IL). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for the normality test. For comparisons of each pair of senile cataract and POAG groups, the differences in quantitative data including age, IOP, AL, and concentration of cytokines were calculated with the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences in categorical data including gender and eyes were determined using the Fisher’s exact probability test. Correlations among cytokines and correlations between cytokine concentrations and subjects’ demographic data (including age, IOP, mean deviation and glaucoma medications) were calculated using the Spearman’s correlation test. For the correction of multi-group comparisons, P values of 0.0083 for the Spearman’s correlation test were considered to be statistically significant at a level of 5% based on Bonferroni’s methods [22].

Results

Patient characteristics

AH samples were collected from 46 patients: 24 patients with POAG and 22 patients with cataract (non-glaucoma). The characteristics of patients, including age, gender, preoperative IOP, axial length (AL), mean deviation (MD), and glaucoma medications are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. Preoperative IOP was higher in POAG eyes (22.22±7.40) than in cataract eyes (14.04±2.98), as calculated by a Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Cataract | POAG |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 22 | 24 |

| Eye (left/right) | 12/10 | 11/13 |

| Sex (male/female) | 10/12 | 10/14 |

| Age, y | ||

| Mean ± SD | 65.59 ± 10.21 | 62.21 ± 9.32 |

| Range | 45–84 | 44–75 |

| Preoperative IOP, mm Hg | ||

| Mean ± SD | 14.04 ± 2.98 | 22.22 ± 7.40** |

| Range | 8.3–21.0 | 9.8–34.2 |

| AL, mm | ||

| Mean ± SD | 24.56 ± 2.27 | 25.00 ± 2.26 |

| Range | 22.50–29.58 | 22.25–29.75 |

| MD in Humphrey visual field analysis, dB | ||

| Mean ± SD | Untested | −17.41 ± 8.98 |

| Range | Untested | −31.02 to −0.94 |

POAG, primary open angle glaucoma, SD, standard deviation; IOP, intraocular pressure; AL, axial length, MD, mean deviation

**P < 0.01, calculated by a Mann-Whitney U test

Table 2.

Glaucoma medications

| Glaucoma medications, | Cataract | POAG |

|---|---|---|

| No. mean ± SD | 0 | 2.5 ± 0.78 |

| Range | 0 | 1–4 |

| β-blockers | 0 | 22(92) |

| Prostaglandin analoguess | 0 | 16(67) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | 0 | 12(50) |

| α2-agonist | 0 | 10(42) |

Comparison of cytokines between POAG patients and cataract patients

The concentrations of the seven cytokines are shown in Table 3. Compared with the senile cataract group, the concentrations of cathepsin D, sNCAM and sVCAM-1 were significantly higher in AH samples from POAG (all P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the levels of BDNF, sICAM-1, MPO, or PAI-1 between the two groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of cytokine levels in the AH of eyes with POAG and cataract

| Cytokine | POAG (pg/ml) | Cataract (pg/ml) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | 0.84 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 0.119 |

| Cathepsin D | 218,382.92 ± 32,671.62 | 178,882.82 ± 27,384.93 | <0.001 |

| sICAM-1 | 283.90 ± 188.16 | 236.46 ± 164.70 | 0.194 |

| MPO | 417.01 ± 600.22 | 290.11 ± 212.17 | 0.680 |

| sNCAM | 11,229.08 ± 2479.73 | 8391.14 ± 1717.89 | <0.001 |

| sVCAM-1 | 13,506.13 ± 8968.03 | 6930.14 ± 2581.25 | 0.007 |

| PAI-1 | 544.45 ± 213.43 | 446.53 ± 220.17 | 0.141 |

POAG, primary open angle glaucoma; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; MPO, myeloperoxidase; sNCAM, soluble neural cell adhesion molecule; sVCAM, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor

P values are calculated by Mann-Whitney U test

Correlation analysis among cytokines in patients with POAG

The correlation analysis among cytokines in POAG patients is shown in Table 4. Statistical analysis revealed high correlations among sICAM-1, sNCAM, sVCAM-1 and PAI-1 (P < 0.0083 in all combinations). The level of sVCAM-1 were significantly associated with the concentration of cathepsin D (P = 0.002, ρ = 0.592). The concentration of PAI-1 was also correlated with MPO (P = 0.005, ρ = 0.551).

Table 4.

Correlations among cytokines in POAG

| ρ/P value | BDNF | Cat D | sICAM-1 | MPO | sNCAM | sVCAM-1 | PAI-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | – | −0.103 | −0.402 | −0.192 | −0.378 | −0.412 | −0.455 |

| Cathepsin D | 0.631 | – | 0.432 | 0.072 | 0.369 | 0.592 | 0.290 |

| sICAM-1 | 0.052 | 0.035 | – | 0.425 | 0.743 | 0.737 | 0.751 |

| MPO | 0.368 | 0.740 | 0.038 | – | 0.312 | 0.269 | 0.551 |

| sNCAM | 0.069 | 0.076 | 0.000* | 0.138 | – | 0.603 | 0.775 |

| sVCAM-1 | 0.046 | 0.002* | 0.000* | 0.204 | 0.002* | – | 0.620 |

| PAI-1 | 0.025 | 0.169 | 0.000* | 0.005* | 0.000* | 0.001* | – |

POAG, primary open angle glaucoma; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Cat D,cathepsin D; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; MPO, myeloperoxidase; sNCAM, soluble neural cell adhesion molecule; sVCAM, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor

Correlation coefficient (ρ) and P values for each pair of cytokines are calculated by the Spearman’s correlation test

The P values are shown on the lower left side and ρ on the upper right side of the table

*Significance level at 5% (P < 0.0083), by Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons

Relationships of the subjects’ demographic data to cytokine concentrations in aqueous humour

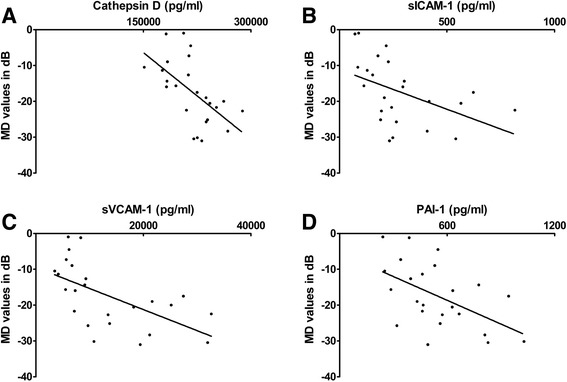

Correlations between the levels of cytokines and clinical Variables in POAG are showed in Table 5. Statistical analysis reveals that age, IOP and glaucoma medications were not significantly correlated with the concentration of cytokines in AH of POAG patients. MD values measured by Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer was significantly associated with the levels of the cathepsin D (P < 0.001; ρ= − 0.668), sICAM-1 (P = 0.003; ρ= − 0.579), sVCAM-1(P < 0.001; ρ= − 0.695), and PAI-1 (P = 0.007; ρ= − 0.533) (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Correlations between the levels of cytokines and clinical variables

| Age (y) | IOP (mm Hg) | Glaucoma Medications(n) | MD (dB) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | P | ρ | P | ρ | P | ρ | P | |

| BDNF | 0.102 | 0.635 | −0.194 | 0.363 | 0.256 | 0.227 | 0.046 | 0.831 |

| Cathepsin D | 0.418 | 0.042 | −0.146 | 0.496 | 0.115 | 0.594 | −0.668 | 0.000* |

| sICAM-1 | 0.030 | 0.891 | −0.130 | 0.543 | −0.444 | 0.030 | −0.579 | 0.003* |

| MPO | 0.023 | 0.916 | −0.036 | 0.868 | −0.192 | 0.369 | −0.340 | 0.104 |

| sNCAM | −0.185 | 0.388 | −0.041 | 0.848 | −0.167 | 0.436 | −0.426 | 0.038 |

| sVCAM-1 | 0.277 | 0.190 | 0.124 | 0.563 | −0.211 | 0.323 | −0.695 | 0.000* |

| PAI-1 | −0.216 | 0.311 | −0.015 | 0.945 | −0.176 | 0.411 | −0.533 | 0.007* |

Correlation coefficient (ρ) and P values are calculated by the Spearman’s correlation test

*Significance level at 5% (P < 0.0083), by Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons

Fig. 1.

Relationships of MD (dB) to cytokine concentrations. The scatter grams showing the correlations between the MD in Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer and the levels of cathepsin D (a), sICAM-1 (b), sVCAM-1 (c) and PAI-1 (d) in AH of eyes with POAG. The x-axes represent the levels of cytokines, and the y-axes represent the MD values (dB).

Discussion

This study, which aimed to identify the biomarkers related to glaucoma has been difficult because the small volume of AH available for sampling. The multiplex bead immunoassay enabled us to measure multiple cytokine levels in a small sample. Thus, multiplex bead immunoassay can be a useful method for assessing biomarkers in AH sample. Moreover, it is a potent technology for introducing laboratory medicine into ophthalmology [23].

Using this technique, we demonstrated that levels of cathepsin D, sNCAM, and sVCAM-1 were significantly increased in POAG patients compared to the cataract group, while the levels of BDNF, sICAM-1, MPO, and PAI-1 were not differ among the groups. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to compare the concentrations of neurodegenerative biomarkers in the AH of patients with glaucoma vs. cataract.

Elevated levels of cathepsin D, sNCAM, and sVCAM-1 cannot be explained simply by an impaired blood-aqueous barrier (BAB). Increased local production in the anterior ocular segment may be another explanation. The alterations detected in the AH may be related to oxidative stress, mitochondrial alterations, apoptosis, tissue disaggregation, and neuronal damage [17]. Among them, oxidative stress has been recognized as a main pathogenic factor for POAG [24]. As age increases, the mitochondrial respiratory function decreases, which increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals in mitochondria [25]. When the levels of free radicals increase and the antioxidant defence is not sufficient, then oxidative stress may damage the HTM. Thus, these proteins whose AH levels are increased in POAG may reflect molecular and cellular damage in the HTM.

We measured the concentrations of three cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) including sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, and sNCAM. To date, we have not found any studies that indicate the presence of the CAM in AH of patients with POAG. CAMs are members of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily that are involved in generating and maintaining cell connections and compose an extensive cell-cell and cell-matrix network [26]. Their presence in the AH indicated that the HTM had been severely damaged. These finding may explain the observation at the molecular level that the HTM undergoes progressive cell loss and cell disaggregation during POAG [27]. The expression of CAMs is induced by inflammatory cytokines [28] and might play a crucial role in inflammatory mechanisms [29].

In the present study, we found that levels of sNCAM and sVCAM-1 were significantly elevated in the AH of patients with POAG. VCAM-1 is an early marker of endothelial activation and dysfunction, leukocyte infiltration, and vascular remodelling [30]. Its expression can be induced by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [31], and elevated concentrations of TNF-α have been found in AH of POAG eyes [32]. In the anterior ocular segment, VCAM-1 can be expressed by an HTM cell [33]. Moreover, some studies have found that the expression of VCAM-1 may be related to oxidative stress; the expression of VCAM-1 can be suppressed because of the inhibition of oxidative stress [34, 35]. The NCAM is a cell adhesion molecule that has been widely implicated in activating some signalling pathways, influencing cell migration, axonal outgrowth, and synaptogenesis [36]. Soluble forms of NCAM have been identified in blood, CSF, and neuronal cell culture media. Altered sNCAM levels in CSF have been observed in neurological disorders including AD [37], MS [38], schizophrenia [39], and bipolar disorder [40]. Evidence showed that sNCAM levels in blood plasma of patients may be used for the differential diagnosis of AD [41, 42]. Moreover, levels of low-molecular-weight forms of NCAM in the serum samples are correlated with the severity of dementia [43]. In the field with glaucoma, a significant increase in NCAM mRNA levels was detected by RT-PCR and Northern blots in cultured optic nerve head astrocytes within 6 h after exposure to elevated pressure [44]. Foets [45] found that the HTM can also express the NCAM, and may be important in the modelling of anterior ocular structures. The concentration of ICAM was also elevated, but there was no significant difference between the control group and the control group, which we thought was related to the sample size.

In this study, we also found that the elevated concentrations of cathepsin D in the AH of POAG. Cathepsin D is the main lysosomal aspartic protease that is expressed in all human cells. It is a protease that plays a crucial role in cell homeostasis since it is involved in both prosurvival (intralysosomal proteolysis of autophagy and endocytosed substrates) and prodeath (proteolysis of cytosolic substrates) processes [46]. On cultured cells, oxidative stress has been found to cause destabilization of lysosomal membranes by the peroxidation of membrane lipids [47]. In the anterior ocular segment, the generation of intralysosomal ROS induces lysosomal membrane permeabilization and the release of cathepsin D into the cytosol, leading to TM cell death [48]. Many altered neuronal proteins that hallmark neurodegenerative diseases (such as the amyloid, α-synuclein, and huntingtin) are physiologic substrates of cathepsin D and would abnormally accumulate if not efficiently be degraded by this enzyme [46]. Abnormally elevated levels of cathepsin D were reported in the CSF of AD patients. Moreover, cathepsin D plays a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of human neurodegenerative diseases. Although the exact pathophysiologic roles of cathepsin D in the AH of POAG patients have not been clarified, increased levels of cathepsin D in the AH of patients with POAG suggest a link between this protein and HTM injury.

We also provide evidence of a correlation between the levels of neurodegenerative biomarkers in the AH and the severity of visual field defects in POAG patients. The MD values were significantly associated with the levels of cathepsin D, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, and PAI-1. However, a large sample size and long-term follow-up are needed to conclude that the cytokine levels in the AH truly reflect the severity of the visual field defect. In addition, statistical analysis reveals that age, IOP and glaucoma medications were not significantly correlated with the concentration of cytokines in the AH of POAG patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the data demonstrated that cathepsin D, sNCAM, and sVCAM-1 levels were significantly increased in the AH of POAG patients compared with controls, and these elevated biomarkers may be related to trabecular meshwork injury.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AH

aqueous humour

- AL

axial length

- BAB

blood-aqueous barrier

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- IOP

intraocular pressure

- MD

mean deviation

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- OCT

Ocular Coherence Tomography

- PAI

plasminogen activator inhibitor

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- POAG

primary open-angle glaucoma

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- sICAM

soluble intercellular adhesion molecule

- sNCAM

soluble neural cell adhesion molecule

- sVCAM

soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule

Authors’ contributions

Design of the Study (YZ, LX, XC); Conduct of the study (YZ, QMY, FG, XC); Collection of samples (YZ, QMY, XC, LX); Analysis and interpretation of the data (YZ, LX); Preparation, review and approval of manuscript (LX, YZ, FG, XC, QMY). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Daping Hospital of the Third Military Medical University (No._47) and adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. We also registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-OOC-16008516) on May 22, 2016. Each patient recruited in this study was given an explanation about the research and signed an informed consent for AH collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yong Zhang, Email: 1320056900@qq.com.

Qinmei Yang, Email: 1539088216@qq.com.

Feng Guo, Email: guofeng013@163.com.

Xia Chen, Email: chenxia1151@163.com.

Lin Xie, Email: Xielin1630@163.com.

References

- 1.Mac NC, Nickells RW. Neuroinflammation in glaucoma and optic nerve damage. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;134:343–363. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Ang LC, Noel DTL, Bidaisee L, Yucel YH. Human glaucoma and neural degeneration in intracranial optic nerve, lateral geniculate nucleus, and visual cortex. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(6):674–678. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.086769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yucel YH, Zhang Q, Weinreb RN, Kaufman PL, Gupta N. Effects of retinal ganglion cell loss on magno-, parvo-, koniocellular pathways in the lateral geniculate nucleus and visual cortex in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22(4):465–481. doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(03)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauthier AC, Liu J. Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection in glaucoma. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89(1):73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowak A, Majsterek I, Przybylowska-Sygut K, Pytel D, Szymanek K, Szaflik J, Szaflik JP. Analysis of the expression and polymorphism of APOE, HSP, BDNF, and GRIN2B genes associated with the neurodegeneration process in the pathogenesis of primary open angle glaucoma. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:258281. doi: 10.1155/2015/258281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayer AU, Keller ON, Ferrari F, Maag KP. Association of glaucoma with neurodegenerative diseases with apoptotic cell death: Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(1):135–137. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadun AA, Bassi CJ. Optic nerve damage in Alzheimer's disease. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(90)32621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwagerl AL, Mohan PS, Cataldo AM, Vonsattel JP, Kowall NW, Nixon RA. Elevated levels of the endosomal-lysosomal proteinase cathepsin D in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer disease. J Neurochem. 1995;64(1):443–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda M, Tsukada N, Miyagi K, Yanagisawa N. Increased levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in the cerebrospinal fluid and sera of patients with multiple sclerosis and human T lymphotropic virus type-1-associated myelopathy. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;59(1–2):35–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00023-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartung HP, Michels M, Reiners K, Seeldrayers P, Archelos JJ, Toyka KV. Soluble ICAM-1 serum levels in multiple sclerosis and viral encephalitis. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2331–2335. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welge-Lussen U, May CA, Neubauer AS, Priglinger S. Role of tissue growth factors in aqueous humor homeostasis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12(2):94–99. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streilein JW. Anterior chamber associated immune deviation: the privilege of immunity in the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;35(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(90)90048-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohira S, Inoue T, Iwao K, Takahashi E, Tanihara H. Factors influencing aqueous Proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors in Uveitic glaucoma. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e147080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas JB, Tao Y, Neumaier M, Findeisen P. Cytokine concentration in aqueous humour of eyes with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(5):e381–e388. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X, Zhang K, He W, Yang J, Sun X, Jiang C, Dai J, Lu Y. Proinflammatory status in the aqueous humor of high myopic cataract eyes. Exp Eye Res. 2016;142:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izzotti A, Longobardi M, Cartiglia C, Sacca SC. Proteome alterations in primary open angle glaucoma aqueous humor. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(9):4831–4838. doi: 10.1021/pr1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarado JA, Yeh RF, Franse-Carman L, Marcellino G, Brownstein MJ. Interactions between endothelia of the trabecular meshwork and of Schlemm's canal: a new insight into the regulation of aqueous outflow in the eye. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:148–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchshofer R, Tamm ER. Modulation of extracellular matrix turnover in the trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88(4):683–688. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):238–242. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma RK, Rogojina AT, Chalam KV. Multiplex immunoassay analysis of biomarkers in clinically accessible quantities of human aqueous humor. Mol Vis. 2009;15:60–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker T, Knapp M. A powerful strategy to account for multiple testing in the context of haplotype analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):561–570. doi: 10.1086/424390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusnak S, Vrzalova J, Sobotova M, Hecova L, Ricarova R, Topolcan O. The measurement of intraocular biomarkers in various stages of proliferative diabetic retinopathy using multiplex xMAP technology. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:424783. doi: 10.1155/2015/424783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacca SC, Bolognesi C, Battistella A, Bagnis A, Izzotti A. Gene-environment interactions in ocular diseases. Mutat Res. 2009;667(1–2):98–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacca SC, Izzotti A, Rossi P, Traverso C. Glaucomatous outflow pathway and oxidative stress. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(3):389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DP L, Tian L, O'Neill C, King NJ. Regulation of cellular adhesion molecule expression in murine oocytes, peri-implantation and post-implantation embryos. Cell Res. 2002;12(5–6):373–383. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sacca SC, Gandolfi S, Bagnis A, Manni G, Damonte G, Traverso CE, Izzotti A. From DNA damage to functional changes of the trabecular meshwork in aging and glaucoma. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;29:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anastassiou G, Esser M, Bader E, Steuhl KP, Bornfeld N. Expression of cell adhesion molecules and tumour infiltrating leucocytes in conjunctival melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2004;14(5):381–385. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armentero M, Levandis G, Bazzini E, Cerri S, Ghezzi C, Blandini F. Adhesion molecules as potential targets for neuroprotection in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43(3):663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewers M, Mielke MM, Hampel H. Blood-based biomarkers of microvascular pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barks JL, McQuillan JJ, Iademarco MF. TNF-alpha and IL-4 synergistically increase vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 1997;159(9):4532–4538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balaiya S, Edwards J, Tillis T, Khetpal V, Chalam KV. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) levels in aqueous humor of primary open angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:553–556. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S19453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkumas KM, Stamer WD. Protein markers and differentiation in culture for Schlemm's canal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2012;96(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalin R, Righi A, Del RA, Bagchi D, Generini S, Cerinic MM, Das DK. Activin, a grape seed-derived proanthocyanidin extract, reduces plasma levels of oxidative stress and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin) in systemic sclerosis. Free Radic Res. 2002;36(8):819–825. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000005249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi N, Mita S, Yoshida K, Honda T, Kobayashi T, Hara K, Nakano S, Tsubokou Y, Matsuoka H. Celiprolol activates eNOS through the PI3K-Akt pathway and inhibits VCAM-1 via NF-kappaB induced by oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2003;42(5):1004–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000097547.35570.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnanapavan S, Ho P, Heywood W, Jackson S, Grant D, Rantell K, Keir G, Mills K, Steinman L, Giovannoni G. Progression in multiple sclerosis is associated with low endogenous NCAM. J Neurochem. 2013;125(5):766–773. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnanapavan S, Grant D, Illes-Toth E, Lakdawala N, Keir G, Giovannoni G. Neural cell adhesion molecule--description of a CSF ELISA method and evidence of reduced levels in selected neurological disorders. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;225(1–2):118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ottervald J, Franzen B, Nilsson K, Andersson LI, Khademi M, Eriksson B, Kjellstrom S, Marko-Varga G, Vegvari A, Harris RA, et al. Multiple sclerosis: identification and clinical evaluation of novel CSF biomarkers. J Proteome. 2010;73(6):1117–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Kammen DP, Poltorak M, Kelley ME, Yao JK, Gurklis JA, Peters JL, Hemperly JJ, Wright RD, Freed WJ. Further studies of elevated cerebrospinal fluid neuronal cell adhesion molecule in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(9):680–686. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantovic-Stefanovic M, Petronijevic N, Dunjic-Kostic B, Velimirovic M, Nikolic T, Jurisic V, Lackovic M, Damjanovic A, Totic-Poznanovic S, Jovanovic AA, et al. sVCAM-1, sICAM-1, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 levels in bipolar disorder type I: acute, longitudinal, and therapeutic implications. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016:1–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wakabayashi Y, Uchida S, Funato H, Matsubara T, Watanuki T, Otsuki K, Fujimoto M, Nishida A, Watanabe Y. State-dependent changes in the expression levels of NCAM-140 and L1 in the peripheral blood cells of bipolar disorders, but not in the major depressive disorders. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu G, Jiang Y, Wang P, Feng R, Jiang N, Chen X, Song H, Chen Z. Cell adhesion molecules contribute to Alzheimer's disease: multiple pathway analyses of two genome-wide association studies. J Neurochem. 2012;120(1):190–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todaro L, Puricelli L, Gioseffi H, Guadalupe PM, Lastiri J, Bal DKJE, Varela M, Sacerdote DLE. Neural cell adhesion molecule in human serum. Increased levels in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(2):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ricard CS, Kobayashi S, Pena JD, Salvador-Silva M, Agapova O, Hernandez MR. Selective expression of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM)-180 in optic nerve head astrocytes exposed to elevated hydrostatic pressure in vitro. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;81(1–2):62–79. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foets B, van den Oord J, Engelmann K, Missotten L. A comparative immunohistochemical study of human corneotrabecular tissue. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992;230(3):269–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00176303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vidoni C, Follo C, Savino M, Melone MA, Isidoro C. The role of Cathepsin D in the pathogenesis of human neurodegenerative disorders. Med Res Rev. 2016;36(5):845–870. doi: 10.1002/med.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cesen MH, Pegan K, Spes A, Turk B. Lysosomal pathways to cell death and their therapeutic applications. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y, Epstein DL, Liton PB. Intralysosomal iron induces lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cathepsin D-mediated cell death in trabecular meshwork cells exposed to oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(12):6483–6495. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.