Abstract

Background

Laboratory assays evaluating the effect of DNA sequence variants on BRCA1 mRNA splicing may contribute to classification by providing molecular evidence. However, our knowledge of normal and aberrant BRCA1 splicing events to date has been limited to data derived from assays targeting partial transcript sequences. This study explored the utility of nanopore sequencing to examine whole BRCA1 mRNA transcripts and to provide accurate categorisation of in-frame and out-of-frame splicing events.

Methods

The exon structure of BRCA1 transcripts from a previously studied control lymphoblastoid cell line were assessed using MinION nanopore sequencing of long-range reverse transcriptase-PCR amplicons.

Results

Our study identified and characterised 32 complete BRCA1 isoforms, including 18 novel isoforms which showed skipping of multiple contiguous and/or non-contiguous exons. Furthermore, we show that known BRCA1 exon skipping events, such as Δ(9,10) and Δ21, can co-occur in a single transcript, with some isoforms containing four or more alternative splice junctions. Fourteen novel isoforms were formed entirely from a combination of previously identified alternative splice junctions, suggesting that the total number of BRCA1 isoforms might be lower than the number of splicing events reported previously.

Conclusions

Our results highlight complexity in BRCA1 transcript structure that has not been described previously. This finding has key implications for predicting the translation frame of splicing transcripts, important for interpreting the clinical significance of spliceogenic variants. Future research is warranted to quantitatively assess full-length BRCA1 transcript levels, and to assess the application of nanopore sequencing for routine evaluation of potential spliceogenic variants.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13058-017-0919-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: BRCA1, Splicing, MinION, Nanopore sequencing, Full-length transcript, Exon skipping

Background

Routine diagnostic screening for deleterious variants in the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is typically performed for individuals from suspected high-risk breast (and ovarian) cancer families to identify the genetic cause for their disease. However, an important practical issue associated with genetic testing is the identification of rare sequence variants with unknown clinical significance. Interpreting the clinical meaning of unclassified variants is a key challenge facing the future of genomic-based health initiatives [1].

Multifactorial likelihood analysis is the most accepted approach for assessing cancer risk associated with unclassified BRCA1 variants and has been successful in classifying hundreds of variants since it was developed [2, 3] (http://brcaexchange.org/). However, the multifactorial likelihood model is limited by the amount of information available from the variant carrier (tumour histopathology), the family of the variant carrier (co-segregation, family history information) and additional information, such as co-occurrence with a pathogenic variant. Numerous studies have shown that the effect of a variant of unknown clinical significance on BRCA1 mRNA splicing may contribute to classification by offering molecular evidence [4–7]. Moreover, to classify variants using a combination of bioinformatic and in-vitro splicing data, Spurdle et al. [8] proposed five-tier splicing classification guidelines (Class 5, pathogenic; Class 4, likely pathogenic; Class 3, uncertain; Class 2, likely not pathogenic; Class 1, not pathogenic). These guidelines were subsequently improved after a multicentre study carried out by the international ENIGMA consortium [6].

Determining which mRNA splice isoforms are abnormal and potentially deleterious can be challenging. The ENIGMA Splicing Working Group recently undertook a comprehensive analysis to characterise numerous ‘naturally occurring’ mRNA splice isoforms for BRCA1 to aid in the interpretation of in-vitro splicing assays [9]. This study identified more than 60 BRCA1 mRNA isoform events occurring in breast and/or blood cells. However, it remains unclear whether these individual splicing events can co-occur in the same BRCA1 transcript, as PCR-based and sequencing-based technologies used to assess splicing events typically interrogate only a fraction of the whole transcript(s). Pathogenic (or Class 5) variants that cause mRNA splicing changes are expected to disrupt protein function either through truncation or in-frame deletion of important regions of the encoded proteins. Using technologies that only examine a section of mRNA transcripts for variant classification may therefore lead to a misinterpretation of in-frame or out-of-frame splicing events.

DNA sequencing technology based on nanopore sequencing generates read lengths that greatly exceed those of more commonly used Sanger sequencing and massively parallel sequencing platforms. Moreover, nanopore sequencing has been demonstrated to characterise the complex exon structure of mRNA transcripts from genes expressing a large number of isoforms [10]. To our knowledge, single-molecule sequencing technologies (MinION [11] and PacBio [12]) that enable long sequence reads have yet to be employed to resolve the exon structure of whole BRCA1 mRNA transcripts. In this study, we explored the utility of long-range reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR with nanopore sequencing to identify novel BRCA1 isoforms and the co-occurrence of known exon skipping events.

Methods

RNA sample

A human lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) derived from a female healthy control, used in a previously reported study [7], was cultured with cycloheximide to prevent nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD), as described previously [5]. RNA was extracted from the cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The study participant provided written informed consent for research studies.

cDNA synthesis

cDNA synthesis was carried out using oligo(dT) primers (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) and Superscript® III Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty microlitres of resulting cDNA mix was diluted 5-fold in H2O, and 3 μl of the final solution was used for each long-range PCR assay.

PCR assays

Three different protocols were used to generate a pool of PCR amplicons for nanopore sequencing. PCR products were resolved in a 1% agarose gel using electrophoreses.

Protocol 1

Reactions contained 1.3 M betaine (Sigma-Aldrich), 1× KAPA long-range buffer (KAPA Biosystems), 1.75 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM of each primer (BRCA1_1F 5′-GCGCGGGAATTACAGATAAA-3′ and BRCA1_24pR 5′-AAGCTCATTCTTGGGGTCCT-3′), 300 μM of KAPA, 200 μM dNTP mix, and 0.5 units of KAPA Long Range HotStart. Thermal cycling conditions were 94 °C for 4 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at one of a range of temperatures (56.4–62.5 °C; Additional file 1: Figure S2) for 30 seconds, and 68 °C for 12 minutes, with a final extension of 72 °C for 12 minutes.

Protocol 2

PCR reactions contained 1 M betaine, 1× KAPA long-range buffer, 2 mM of MgCl2, 0.7 μM of each primer (BRCA1_1F and BRCA1_24pR), 200 μM dNTP mix, and 0.5 units of KAPA Long Range HotStart. Thermal cycling conditions were 94 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 55.7–62.5 °C (Additional file 1: Figure S2) for 30 seconds, and 68 °C for 7 minutes, before a final extension of 72 °C for 7 minutes.

Protocol 3

Reactions contained 1 M betaine, 1× KAPA long-range buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.7 μM of each primer (BRCA1_1F and BRCA1_24pR), 200 μM dNTP mix, and 0.5 units of KAPA Long Range HotStart. Thermal cycling conditions were 94 °C for 2 minutes, then eight cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 66 °C for 30 seconds (decreasing 1 °C each cycle), and 68 °C for 7 minutes, followed by 30 additional cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 59 °C for 30 seconds, and 68 °C for 7 minutes, before a final extension of 72 °C for 7 minutes.

Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was carried out using Applied Biosystems Big Dye Terminator version 3.1 to confirm PCR products as described previously [13]. The Geneious® Multiple Sequence Aligner tool was used to match the Sanger sequence of the sample with the predicted isoform as a reference sequence.

MinION library preparation, sequencing and alignment

The Oxford Nanopore MinION Genomic DNA Sequencing Kit (R9 flow cell chemistry) was used to prepare the DNA libraries according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, PCR products were purified and then quantified using the Qubit® Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) followed by end repair and dA tailing using the NEBNext Ultratm End Repair/dA-Tailing Module (New England BioLabs Inc.). The DNA library entailing adaptor ligation and purification of double-stranded DNA with hairpin adaptor was prepared using the Nanopore Sequencing Kit SQK-NSK007 (R9 version). The MinKNOW program was used for running MinION for 48 hours. Additional sample mix was applied to the flow cell when the number of pores being used was less than 20, until the entire sample was used. The raw electrical signal was uploaded to Metrichor (version 1.107), using the 2D Basecalling RNN for SQK-NSK007 which returned basecall data in MinION fast5 file format. The Poretools package was used to extract fasta files for high-quality 2D reads [14]. Sequence reads were mapped by the Genomic Mapping and Alignment Program (GMAP) [15] using the Linux command lines gmap -g [ReferenceSequence].fasta -f 2 -n 0 -t 16 [SequencesToAlign].fasta > [alignmentFile].gff3 as gmap -g BRCARD1_geneseq.fasta -f 2 -n 0 -t 16 all.fasta > all.gff3. The output file was manipulated using an in-house R script to select for reads spanning the full length of the gene by ensuring it contained sequences from the first and last exons. The full-length reads were then grouped into isoforms based on their composition of exons and introns.

Results

PCR amplification of full-length BRCA1 cDNA

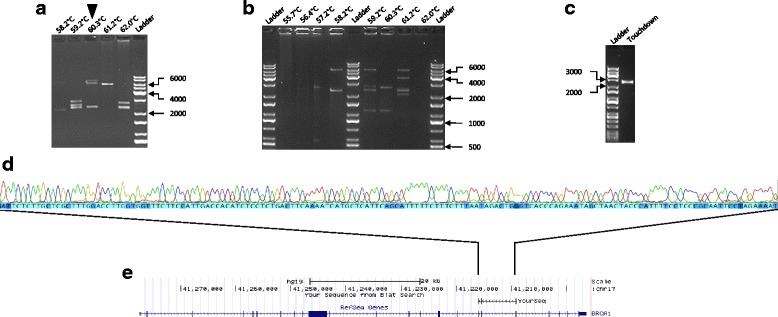

Blood-based products such as lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) have been widely used as a cell model for analysing BRCA1 splicing changes in the clinical setting for variant evaluation [9]. For this study, we assessed RNA from a healthy control LCL that was used previously for an international workshop, led by the ENIGMA Consortium, comparing mRNA splicing assay protocols between laboratories [7]. To obtain full-length BRCA1 transcripts, we carried out long-range RT-PCR for BRCA1 transcripts using primers targeting the 3′ end of exon 1 and the 5′ end of exon 24 to generate a 5.8-kb amplicon (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Amplified products from repeat assays for a single LCL were visualised by gel electrophoresis, revealing a difference in patterns of amplicon sizes and suggesting variability in isoform selection and amplification during the PCR cycles (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Figure S2). PCR products that were consistent by size with a full-length BRCA1 isoform (NM_007294.3, encoding the full-length BRCA1 protein) were observed in 28/47 PCR assays. A preliminary assessment of fragments from 10 PCR assays by Sanger sequencing confirmed BRCA1 identity (Fig. 1) prior to sequencing using MinION, suggesting a range of BRCA1 isoforms were amplified. To maximise the number of whole BRCA1 transcripts to be assessed by nanopore sequencing, amplified products were pooled from all 47 PCR assays using cDNA synthesised from a single LCL RNA sample.

Fig. 1.

Example of fragments obtained from different long-range PCR assays from a LCL. Three different protocols were used to generate a pool of PCR amplicons for nanopore sequencing: a Protocol 1, b Protocol 2 and c Protocol 3. Primer annealing temperature indicated above each lane. Reference markers labelled for size in base pairs. d. Sanger sequence trace of PCR products in (a) (indicated by black triangle). e. BLAT alignment tool showing sequence match to BRCA1 using the UCSC Genome Browser

BRCA1 isoform discovery and annotation

A total of 117,504 reads were obtained from MinION sequencing run from two DNA libraries (Library 1 = 105,482 reads; Library 2 = 12,022 reads) derived from pooled RT-PCR products on a R9 flow cell over a period of 48 hours. Approximately 21% of 2D reads containing both template and complement strand with a Q-value of 9 were obtained, of which 95% aligned to the target sequence. Reads failing the 2D filter were possibly due to shearing of DNA by pipetting or incomplete ligation of hairpin adaptors, thus resulting in shorter reads lacking a complementary strand signal. Our library contained pooled PCR products obtained from cDNA generated from BRCA1 and BARD1 (part of a separate study) transcripts. Nanopore sequencing resulted in 10.7% of passed 2D reads aligning to BRCA1 and a higher proportion (84.4%) of passed 2D reads aligned to a shorter (≤2 kb) BARD1 cDNA sequence. A summary of the mapping and filtering process is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S3. As a result of our stringent filtering criteria (2D reads that contain both exon 1 and exon 24 of BRCA1), a total of 177 reads were identified that revealed the complete structure of different BRCA1 isoforms.

A total of 32 BRCA1 isoforms (including full length; Fig. 2) were resolved with at least one sequencing read using a conservative mapping approach (GMAP) (Table 1). Of these, 20 isoforms have not been described previously. Of the 32 isoforms amplified by long-range RT-PCR, 23 lacked all or part of the largest BRCA1 exon (exon 11; 3426 bases) (Table 1). Ten of these 23 isoforms contained a Δ11q splicing event rather than the complete skipping of exon 11. This result suggests that long-range RT-PCR assays were selective for shorter amplicons corresponding to smaller (<4 kb) isoforms and that the sequencing results from MinION may not be quantitative. Furthermore, the stringent quality control requirement for passed 2D reads would also eliminate DNA strands that may have been accidentally sheared by pipetting during library generation, thus potentially reducing quantitative measurement. The remaining nine of the detected transcripts were greater than 5 kb in length and included the full-length and Δ9,10 isoforms (Table 1), which have been shown previously to be ‘predominant’ transcripts in blood and breast cells using semi-quantitative measures [9]. It is therefore possible that amplicon selection during long-range RT-PCR cycles may also have been influenced by the relatively high proportion of transcript levels in a pool of BRCA1 expressed isoforms.

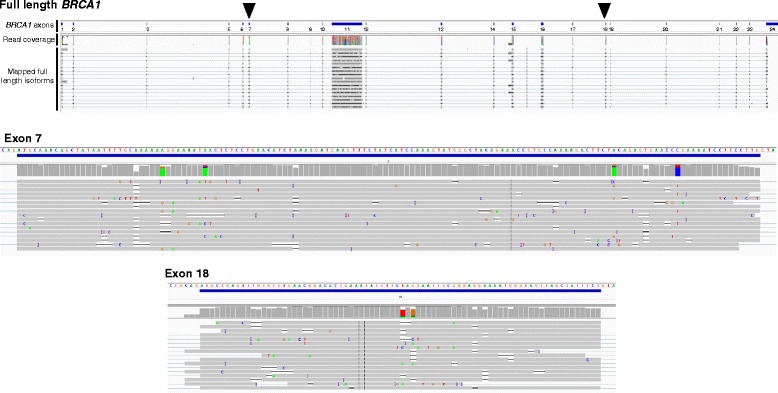

Fig. 2.

Sequencing of the full-length BRCA1 transcript. Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) screenshots for the whole gene, along with close-up views of exons 7 and 18 (also highlighted by black triangles on full-length BRCA1). BRCA1 exons are indicated and represented as blue solid rectangles. Each MinION sequence read with perfect homology to the reference sequence shown in grey. Mismatches shown in colour and indicated by base

Table 1.

BRCA1 isoforms identified by long-range PCR and nanopore sequencing

| Isoform designation | RNA | Size of isoform (bp) | Number of MinION reads | In-frame/out-of-frame | Deleted protein domain(s)a | Previously described by Colombo et al. [9]b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ11q | r.788_4096del | 3898 | 31 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ9,10,11q | r.548_670del + r.788_4096del | 3775 | 27 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Full length | – | 7207 | 17 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ10-17 | r.594_5074del | 2726 | 14 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ9,11q | r.548_593del + r.788_4096del | 3852 | 10 | Out-of-frame | – | Yes |

| 11Δ3110 | r.788_3897del | 4093 | 8 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ1Aq,9,10,11q,12-15,16p | r.-25_-20del + r.548_670del + r.788_4804 | 3061 | 7 | In-frame | – | No |

| Δ14 | r.4358_4484del | 7080 | 6 | Out-of-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ10,11,17 | r.594_ 4096del + r.4987_5074del | 3616 | 5 | In-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ1Aq,11Δ3110,Δ14p,15-17 | r.-25_-20del + r.788_3897del + r.4358_4360del + r.4485_ 5074del | 3498 | 5 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ9,10 | r.548_670del | 7084 | 5 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ1Aq,5q,11q,14,21 | r.-25_-20del + r.191_212del + r.788_4096del + r.4358_4484del + r.5278_5332del | 3688 | 5 | Out-of-frame | RING | No |

| Δ3 | r.81_134del | 7153 | 5 | Out-of-frame | RING | Yes |

| Δ9,10,14 | r.548_670del + r.4358_4484del | 6957 | 3 | Out-of-frame | – | No |

| Δ3-23 | r.81_ 5467del | 1820 | 3 | Out-of-frame | RING, BCRT | No |

| Δ2,9,10,11q,▼21 | r.-19_80del + r.548_670del + r.788_4096del + r.74421_74422ins74421 + 873_74421 + 1001 | 3676 | 3 | Out-of-frame (loss of coding start site) | RING | No |

| Δ9-11 | r.548_4096del | 3658 | 3 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ2,9,10,11Δ3110,Δ14,20,22 | r.-19_80del + r.548_670del + r.788_3897del + r.4358_4484del + r.5194_5277del + r.5333_5406del | 3586 | 3 | Out-of-frame (loss of coding start site) | RING, BCRT | No |

| Δ11q,21 | r.788_4096del + r.5278_5332del | 3843 | 3 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ11 | r.671_4096del | 3781 | 2 | In-frame | – | Yes |

| Δ3,11Δ3110 | r.81_134del + r.788_3897del | 4039 | 1 | Out-of-frame | RING | No |

| Δ9,10,21 | r.548_670del + r.5278_5332del | 7029 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ21 | r.5278_5332del | 7152 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | Yes |

| Δ3,9,10,11q | r.81_134del + r.548_670del + r.788_4096del | 3721 | 1 | Out-of-frame | RING | No |

| Δ15-17 | r.4485_ 5074del | 6617 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | Yes |

| 11Δ3110,14,20-22 | r.788_3897del + r.4358_4484del + r.5194_ 5406del | 3753 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ8,11 | r.442_547 + r.671_4096del | 3675 | 1 | Out-of-frame | – | No |

| 11Δ3110,Δ14 | r.788_3897del + r.4358_4484del | 3966 | 1 | Out-of-frame | – | No |

| Δ11q,19,20 | r.788_4096del + r.5153_5193_ + r.5194_5277del | 3773 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

| Δ5,9,10,11q | r.135 _212del + r.548_670del + r.788_4096del | 3697 | 1 | In-frame | RING | No |

| Δ3,9 | r.81_134del + r.548_593del | 7107 | 1 | Out-of-frame | RING | No |

| 11Δ3110,Δ21,23 | r.788_3897del + r.5278_5332del + r.5407_5467del | 3977 | 1 | Out-of-frame | BCRT | No |

bp base pairs, BRCT BRCA1 C-terminal domain, RING RING finger domain, Δ whole or partial exon skipping, ▼ partial intron retention

aOnly clinically important BRCA1 protein domains are shown (ENIGMA BRCA1/2 Gene Variant Classification Criteria, Version 2.5 29 June 2017, https://enigmaconsortium.org/library/general-documents/). Position of amino acid residues denoting BRCA1 protein domains are as follows: RING, 1–101 and BCRT, 1651–1863

bNovel isoforms that are created entirely from previously identified partial or whole exon skipping events are shown in bold

Colombo et al. [9] previously characterised a total of 63 BRCA1 alternative splicing events, 17 of which were detected and further validated in this study. Eighteen of the 20 full-length novel isoforms identified by MinION sequencing were found to contain co-occurring exon skipping events (Table 1). Many of these events found to co-occur, such as Δ(9,10), Δ11q, Δ(9,10,11q) and Δ3, have been identified previously in isolation using partial transcript analyses by Colombo et al. [9]. Of the 20 novel isoforms discovered in this study, 14 were formed entirely from a combination of previously identified alternative splice junctions (Table 1). While these data show that many non-contiguous exon skipping events for BRCA1 mRNA occur concurrently, this analysis was possibly non-quantitative and therefore was unable to establish the relative levels of different transcripts.

Two novel isoforms identified, Δ10-17 (Additional file 1: Figure S4) and Δ3-23, show skipping of multiple contiguous exons generating out-of-frame coding sequences. We are unaware of previous studies that have implemented a PCR-based assay design that has encompassed exons 10–17 or exons 3–23. It is therefore not surprising that a long-range PCR-based approach has for the first time detected such isoforms. It is unlikely that Δ10-17 and Δ3-23 give rise to functional proteins as they lack the BRCA1 C-terminal (BCRT) domain (Table 1). Furthermore, the out-of-frame coding sequences for these isoforms suggest that they would be susceptible to NMD [16].

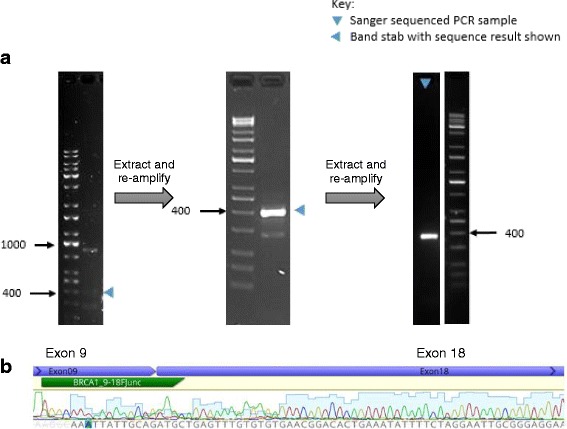

The novel Δ10-17 isoform was selected for validation by Sanger sequencing as the isoform was common within the PCR amplicon library, and had a single junction which was relatively straightforward to amplify. RT-PCR assays using oligonucleotide primers targeting the exon 9–18 junction, followed by Sanger sequencing, confirmed the presence of this novel isoform (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing confirmation of isoform ∆10-17. a RT-PCR analysis of mRNA isolated from a cycloheximide-treated LCL. To obtain a single isoform amplicon with sufficient DNA for sequence analysis, band extraction (shown by blue arrowheads) and re-amplification were carried out twice. The final 408-bp product was analysed by Sanger sequencing. Reference markers labelled for size in base pairs. b Sanger sequence trace of the exon 9–18 novel splice junction from the PCR product indicated in (a). Location of BRCA1_9-18 junction specific PCR primer (BRCA1_9-18FJunc) indicated in green

Together, these results suggest complexity in transcript structure that has not been described previously for BRCA1. Because of the potential error rate of MinION (>10%) [17], a higher read depth would increase the confidence in 19 of the 32 characterised transcripts represented by a relatively small number (n ≤ 3) of reads, and this would be particularly important for potential splice shift events not identified previously.

Co-occurring splicing events and interpretation for variant classification

Determining whether BRCA1 transcripts lead to abnormal and potentially deleterious proteins requires knowledge about the structure of the coding isoforms. Sixteen of the 20 novel isoforms lacked sequences coding for the RING and/or BCRT domains, which have been previously shown to harbour amino acid residues of clinical importance [18], although 14 of these 16 isoforms are out-of-frame and would therefore be susceptible to NMD. The remaining two isoforms, Δ(10,11,17) and Δ(5,9,10,11q), are predicted to be in-frame and may potentially give rise to proteins lacking the clinically significant BCRT and RING domains, respectively.

We detected the predominant splicing events, Δ11q and Δ9,10, which individually would be predicted to generate modified in-frame transcripts that are not considered deleterious based on protein coding. However, our study has shown these splicing events can co-occur with skipping and insertion events causing out-of-frame coding in these isoforms (Table 1). Two examples were the Δ(9,10,21) and Δ(11q,21) isoforms which cause out-of-frame coding due to the exon 21 skipping event. Furthermore, the combination of multiple out-of-frame exon skipping events can result in segments of the resulting transcript being in-frame. For example, Δ10,11 in the Δ(10,11,17) isoform is an out-of-frame deletion, but together with the out-of-frame Δ17 event the isoform returns to being in-frame coding from exon 18 to exon 24. This transcript lacks sequence for the BRCT domain, suggesting that the isoform may avoid NMD and generate a protein that does not retain full BRCA1 function. Obtaining whole transcript information may therefore have important implications for interpreting the biological and clinical significance of spliceogenic variants.

Discussion

Laboratory assays assessing the effect of DNA sequence variants on BRCA1 mRNA splicing may contribute to classification by offering molecular evidence [5, 6]. However, detection of BRCA1 splicing events to date has been restricted to assays targeting segments within BRCA1 transcripts [9]. For the first time, we show that MinION nanopore sequencing of long-range PCR amplicons is able to resolve the exon structure of whole BRCA1 transcripts, enabling accurate prediction of in-frame and out-of-frame coding events. Our study identified 20 novel BRCA1 isoforms, 18 of which contained multiple individual splicing events. Many of the individual BRCA1 exon skipping events and splice donor shifts (e.g. Δ1Aq, Δ5q and 11q) have been found previously [9]; however, our data indicate that these events can co-occur within single transcripts. Such complexity in transcript structure has not been described previously for BRCA1 and has potential implications for interpreting the biological and clinical significance of spliceogenic variants.

While our work highlights that many BRCA1 mRNA splicing events occur concurrently, our non-quantitative study was unable to establish the likelihood of such events being expressed in the same transcript. If future studies show that many of the detected BRCA1 exon skipping events exclusively co-occur, then the total number of isoforms might be lower than the number of splicing events reported previously by Colombo et al. [9]. Such a finding would suggest similar splicing patterns may also exist for genes other than BRCA1. Further studies will therefore be required to measure the cellular levels of sequenced isoforms, and to investigate the possibility of further transcript complexity due to splice site shifts involving a small number of nucleotides. Such studies will require improved data analysis tools to take full advantage of the sequencing information generated, although we note that this field continues to advance as evidenced in a recent report by Hu et al. [19].

The ENIGMA Splicing Working Group previously led a multicentre study which highlighted methodological issues that confounded the interpretation of splicing results [6]. A major reason for these issues was determined to be PCR assay design and the restrictive positioning of primers which prevented detection of additional naturally occurring isoforms. Our follow-up study has been successful in demonstrating the capability of the MinION device to characterise the exon structure of whole BRCA1 transcripts. Together, our results highlight the potential of this technology to overcome limitations of traditional PCR-based techniques.

Conclusions

Our study highlights complexity in BRCA1 transcript structure that has not been described by previously reported studies. Assessment of whole BRCA1 transcripts is now possible and has key implications for predicting translation frame of splicing transcripts, which is important for interpreting the clinical significance of spliceogenic variants. Future research is warranted to quantitatively assess full-length BRCA1 transcript levels, to detect additional novel isoforms involving small nucleotide shifts and to assess the application of nanopore sequencing for routine evaluation of potential spliceogenic variants. Furthermore, the application of MinION or similar platforms may be extended to other disease-associated genes to establish whether they display similar complex splicing patterns to BRCA1.

Acknowledgements

MAK and LCW jointly supervised this work. The authors wish to thank Heather Thorne, Eveline Niedermayr, all of the kConFab research nurses and staff, the heads and staff of the Family Cancer Clinics, and the Clinical Follow Up Study (which has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Cancer Australia and the National Institute of Health (USA)) for their contributions to this resource, and the many families who contribute to kConFab.

Funding

The research was supported by Cancer Society of New Zealand Canterbury/West Coast Division, and the Jim and Mary Carney Charitable Trust. LCW was supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand Rutherford Discovery Fellowship. ABS is supported by an Australian NMHRC Senior Research Fellowship. kConFab is supported by a grant from the National Breast Cancer Foundation, and previously by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Queensland Cancer Fund, the Cancer Councils of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the Cancer Foundation of Western Australia.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author for additional information on how to obtain the study data.

Abbreviations

- BCRT

BRCA1 C-terminal domain

- BLAT

BLAST-like alignment tool

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- ENIGMA

Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles

- GMAP

Genomic Mapping and Alignment Program

- LCL

Lymphoblastoid cell line

- NMD

Nonsense-mediated decay

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RT

Reverse transcriptase

Additional file

is Figure S1 Showing primer design to span BRCA1 cDNA. Primers indicated by arrows positioned on exon 1 and exon 24. Full-length transcript is 7.2 kb. Length of full length amplicon is 5.8 kb. Figure S2 showing results from 47 BRCA1 RT-PCR assays. 2 μl of each reaction was visualised on a 1% agarose gel. Samples that underwent MinION sequencing in Sample 1 or Sample 2 are indicated, and long-range PCR reactions where we confirmed fragments were specific to BRCA1 by Sanger sequencing. 2 μl of each reaction was run on 1% agarose gels. A Protocol 1. B Protocol 2. C Protocol 3. Primer annealing temperature indicated above each lane. Reference markers labelled for size in base pairs. Figure S3 showing a schematic of the nanopore sequencing read filtering steps applied in the study. Figure S4 showing sequencing of the full-length BRCA1 Δ10-17 isoform. Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) screenshots shown for the whole gene, along with close-up views of exons 9 and 18 (also highlighted by black triangles). BRCA1 exons are indicated and represented as blue solid rectangles. Each MinION sequence read with perfect homology to the reference sequence is shown in grey. Mismatches are shown in colour and indicated by base. (DOCX 3674 kb)

Authors’ contributions

LCW and MAK conceived of, designed and coordinated the study. LCdJ and SC carried out the nanopore sequencing. LCdJ performed the bioinformatic analyses with expert support from SC, AM, VL and GARW. LCdJ carried out the molecular assays. kConFab Investigators generated and provided the cell line as part of an approved project led by ABS. LCdJ and LCW drafted the manuscript. All authors read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the University of Otago Ethics Committee (H14/131). Informed consent was obtained from the participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13058-017-0919-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Lucy C. de Jong, Email: lucy.c.dejong@gmail.com

Simone Cree, Email: simone.macmil@otago.ac.nz.

Vanessa Lattimore, Email: vanessa.lattimore@otago.ac.nz.

George A. R. Wiggins, Email: george.wiggins@otago.ac.nz

Amanda B. Spurdle, Email: Amanda.Spurdle@qimrberghofer.edu.au

kConFab Investigators, Email: heather.thorne@petermac.org.

Allison Miller, Email: allison.miller@otago.ac.nz.

Martin A. Kennedy, Email: martin.kennedy@otago.ac.nz

Logan C. Walker, Phone: +64 3 364 0544, Email: logan.walker@otago.ac.nz

References

- 1.Cheon JY, Mozersky J, Cook-Deegan R. Variants of uncertain significance in BRCA: a harbinger of ethical and policy issues to come? Genome Med. 2014;6(12):121. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):535–44. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, Hogervorst FB, Monteiro AN, Nathanson KL, Radice P, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Tavtigian S, Wappenschmidt B, et al. ENIGMA—Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles: an international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):2–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.21628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindor NM, Guidugli L, Wang X, Vallee MP, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian S, Goldgar DE, Couch FJ. A review of a multifactorial probability-based model for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS) Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):8–21. doi: 10.1002/humu.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker LC, Whiley PJ, Couch FJ, Farrugia DJ, Healey S, Eccles DM, Lin F, Butler SA, Goff SA, Thompson BA, et al. Detection of splicing aberrations caused by BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence variants encoding missense substitutions: implications for prediction of pathogenicity. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(6):E1484–505. doi: 10.1002/humu.21267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker LC, Whiley PJ, Houdayer C, Hansen TV, Vega A, Santamarina M, Blanco A, Fachal L, Southey MC, Lafferty A, et al. Evaluation of a 5-tier scheme proposed for classification of sequence variants using bioinformatic and splicing assay data: inter-reviewer variability and promotion of minimum reporting guidelines. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(10):1424–31. doi: 10.1002/humu.22388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiley PJ, de la Hoya M, Thomassen M, Becker A, Brandao R, Pedersen IS, Montagna M, Menendez M, Quiles F, Gutierrez-Enriquez S, et al. Comparison of mRNA splicing assay protocols across multiple laboratories: recommendations for best practice in standardized clinical testing. Clin Chem. 2014;60(2):341–52. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.210658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spurdle AB, Couch FJ, Hogervorst FB, Radice P, Sinilnikova OM, Group IUGVW Prediction and assessment of splicing alterations: implications for clinical testing. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1304–13. doi: 10.1002/humu.20901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo M, Blok MJ, Whiley P, Santamarina M, Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Romero A, Garre P, Becker A, Smith LD, De Vecchi G, et al. Comprehensive annotation of splice junctions supports pervasive alternative splicing at the BRCA1 locus: a report from the ENIGMA consortium. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(14):3666–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolisetty MT, Rajadinakaran G, Graveley BR. Determining exon connectivity in complex mRNAs by nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 2015;16:204. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0777-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain M, Fiddes IT, Miga KH, Olsen HE, Paten B, Akeson M. Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):351–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinforma. 2015;13(5):278–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens AJ, Stuffrein-Roberts S, Cree SL, Gibb A, Miller AL, Doudney K, Aitchison A, Eccles MR, Joyce PR, Filichev VV, et al. G-quadruplex structures and CpG methylation cause drop-out of the maternal allele in polymerase chain reaction amplification of the imprinted MEST gene promoter. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loman NJ, Quinlan AR. Poretools: a toolkit for analyzing nanopore sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(23):3399–401. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu TD, Watanabe CK. GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1859–75. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrin-Vidoz L, Sinilnikova OM, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Lenoir GM, Mazoyer S. The nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway triggers degradation of most BRCA1 mRNAs bearing premature termination codons. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(23):2805–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ip CLC, Loose M, Tyson JR, de Cesare M, Brown BL, Jain M, Leggett RM, Eccles DA, Zalunin V, Urban JM, et al. MinION Analysis and Reference Consortium: Phase 1 data release and analysis. F1000Res. 2015;4:1075. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7201.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ENIGMA BRCA1/2 Gene Variant Classification Criteria. https://enigmaconsortium.org/library/general-documents/

- 19.Hu J, Uapinyoying P, Goecks J. Interactive analysis of long-read RNA isoforms with Iso-Seq Browser. bioRxiv 2017:p.102905.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for additional information on how to obtain the study data.