Abstract

Sex steroids, also known as gonadal steroids, are oxidized with hydroxylation by cytochrome P450, glucuronidation by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, sulfation by sulfotransferase, andO-methylation by catechol O-methyltransferase. Thus, it is important to determine the process by which inflammation influences metabolism of gonadal hormones. Therefore, we investigated the mechanism of metabolic enzymes against high physiologic inflammatory responsein vivo to study their biochemical properties in liver diseases. In this study, C57BL/6N mice were induced with hepatic inflammation by diethylnitrosamine (DEN) exposure. We observed upregulation of Cyp19a1, Hsd17b1, Cyp1a1, Sult1e1 in the DEN-treated livers compared to the control-treated livers using real time PCR. Moreover, the increased Cyp19a1 and Hsd17b1 levels support the possibility that estrogen biosynthesis from androgens are accumulated during inflammatory liver diseases. Furthermore, the increased levels of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 in the hydroxylation of estrogen facilitated the conversion of estrogen to 2- or 4-hydroxyestrogen, respectively. In addition, the substantial increase in the Sult1e1 enzyme levels could lead to sulfate conjugation of hydroxyestrogen. The present information supports the concept that inflammatory response can sequester sulfate conjugates from the endogenous steroid hormones and may suppress binding of sex steroid hormones to their receptors in the whole body.

Keywords: liver, inflammation, sex steroid hormone, steroid metabolic enzyme, cytochrome enzyme

Introduction

Steroid biosynthesis is initiated by the removal of a 6-carbon residue from the side chain of cholesterol. The cleavage reaction converts C27 cholesterol to C21 pregnenolone and involves the side-chain cleavage enzyme desmolase (Cyp11A1) in the mitochondria of steroid-producing cells of gonads and adrenal gland. Steroid hormones are classified into five groups: glucocorticoid, mineralcorticoid, progestogen, estrogen, and androgen. The steroidogenic pathways leading to the production of androgens and estrogens in the testes and ovaries require a number of oxidative enzymes. In gonads, steroid-producing cells contain the steroid 17α-monooxygenase (Cyp17a1) that enables pregnenolone to be converted to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)[1]. As soon as androstenedione is generated from DHEA by the 3β-Hsd enzyme[2], it is converted to testosterone by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Hsd17b1)[1]. Endogenous estrogens (estrone and estradiol) are generated from C19 androgen (testosterone and androstenedione) by Cyp19a1, an aromatase enzyme[3].

All sex steroids are oxidized with hydroxylation by cytochrome P450, glucuronidation by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, sulfation by sulfotransferase, andO-methylation by catechol O-methyltransferase 1 (Comt1)[4–7]. When estrogen metabolites are identified in the liver and extrahepatic tissues, high levels of cytochrome P450 are involved with hydroxylation through 2-, 4-, 6a-, 6b-, 7a-, 12b-, 15a-, 15b-, 16a-, and 16b-hydroxylase enzymes in vivo and in vitro[8,9]. As a catechol metabolite of estradiol, 2-,4-hydroxyestradiol can be subsequently O-methylated to monomethoxy estradiol metabolites by Comt1[10]. Changes in the expression level of estrogen-metabolizing cytochrome enzyme isoforms alter the intensity of the action of estrogen and the profile of its physiologic effect in liver and target tissues. Estrogen sulfotransferase 1E1 (Sult1e1) sulfonates estrogens to biologically inactive estrogen sulfates[11]. The inactive estrogens can be transformed into active estrogens by the sulfatase pathway, involving the enzyme steroid sulfatase (STS), which converts E1-S to E1 and E2-S to E2[12].

It is generally accepted that steroid suppresses inflammation, but there is not enough evidence that it is responsible for the alterations of steroid profiles in inflammation. Although low levels of DHEA and androgens were observed in chronic inflammation, local metabolism of androgens and estrogens linked with suppression or promotion of inflammation[13]. Furthermore, inflammatory conditions provide a unique property for exploring the interface of sex steroids and immune response[14].

The presence of sex steroids in inflammatory processes propelled us to determine whether they promote inflammation-associated diseases or suppress the inflammatory response by various metabolic processes. To address the role of sex steroids in inflammatory liver diseases, we examined the development of DEN-induced inflammations in C57BL/6N mice. In this study, we will investigate that inflammation disrupts the action of sex steroid hormone metabolism and that sex hormones serve as a regulator for hepatocellular inflammation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Diethylnitrosamine (DEN) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions were made by dissolving in distilled water and diluted with saline when needed.

Antibodies

Antibodies specific for a rabbit anti-Cyp1A1, antibody (13241-1-AP), and a rabbit anti-SULT1E1 (24889-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for p53 (sc-126) and beta-actin (sc-1616) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cyp19a1 antibody (#14528) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA).

Animals

C57BL/6N mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facility at Chungnam National University and fed standard chow with water providedad libitum. All mouse experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the Chungnam National University Animal Care Committee. For acute DEN experiments, 6-week-old mice were administered DEN (100 mg/kg bodyweight) in a 0.9% saline solution by i.p. injection, and livers were isolated at the indicated time points following injection.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and qRT-PCR

Total RNA extracts from mouse liver were prepared using the Trizol reagent (Qiagen, MD, USA). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed at 42°C for 50 minutes using 1 mg of total RNA and 200 units of SuperScript II together with oligo (dT) primers and reagents provided by Life Technologies. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using specific primers (Table 1), an Excel Taq SYBR Green (TQ1100, SMOBIO), and a Stratagene Mx-3000P (Agilent technologies, CA, USA) equipped with a 96-well optical reaction plate. All experiments were run in triplicate, and mRNA values were calculated based on the cycle threshold and monitored for an amplification curve.

Tab.1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR analysis

| Gene name | Gene symbol | Upper primer (5' - 3') | Lower primer (5' - 3') |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin 1 alpha | Il-1α | AGTATCAGCAACGTCAAGCAA | TCCAGATCATGGGTTATGGACTG |

| Interleukin 6 | Il-6 | CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG | AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG |

| Interleukin 1 beta | Il-1β | GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG | CTGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACA |

| Hepatocyte growth factor | Hgf | TTCATGTCGCCATCCCCTATG | CCCCTGTTCCTGATACACCT |

| Cytochrome P450 1A1 | Cyp1a1 | GACCCTTACAAGTATTTGGTCGT | GGTATCCAGAGCCAGTAACCT |

| Cytochrome P450 1B1 | Cyp1b1 | CACCAGCCTTAGTGCAGACAG | GAGGACCACGGTTTCCGTTG |

| Catechol-O methyl transferase | Comt | CTGGGGGTTGGTGGCTATTG | CCCACTCCTTCTCTGAGCAG |

| 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | Hsd17b1 | ACTTGGCTGTTCGCCTAGC | GAGGGCATCCTTGAGTCCTG |

| 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 | Hsd17b2 | ATGAGCCCGTTTGCCTCTG | CCACAGGTAACAAGTCTTGG |

| Cytochrome P450 19A1 | Cyp19a1 | ATGTTCTTGGAAATGCTGAACCC | AGGACCTGGTATTGAAGACGAG |

| Cytochrome P450 7A1 | Cyp7a1 | AGCCGATTATCAGCGAAAGCC | GCATCCAAAGGTTTGCCTTGT |

| Estrogen sulfotransferase 1E1 | Sult1e1 | ATGGAGACTTCTATGCCTGAGT | ACACAACTTCACTAATCCAGGTG |

| Glyceraldehyde3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Gapdh | GCTGAGTATGTCGTGGAGTC | TTGGTGGTGCAGGATGCATT |

Plasma ALT level

Mouse blood samples were allowed to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation for 30 minutes at 2,348 ×g. Serum samples were removed without disturbing the gel layers. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were determined using the FUJIFILM DRICHEM slides (3250, fujifilm, Japan).

Western blotting

Liver samples were homogenized in lysis buffer [10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) at 4°C for 30 minutes. Protein was quantified using the protein assay (#21011, Intron, Korea), and proteins were resolved on 7.5%-10% SDS/ PAGE gels. The membranes were blocked for 1 hour in tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and 5% skim milk and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody (see above) in the same buffer. The blots were then washed three times in TBS-T for 15 minutes to remove excess antibody, and then the membranes were incubated for 2 hours with secondary antibodies in TBS-T+ 5% (g/vol) skim milk: (AE-1475 Bioss, Wobrun, MA, USA) or anti-mouse (bs-0296G). Following three washes in TBS-T, proteins were detected with ECL solution (XLS025-0000, Cyanagen, bologna, Italia) and Chemi Doc (Fusion Solo, Vilber Lourmat, France).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean±SEM. Differences between means were obtained by Student's t-test was performed using Graph Pad Software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Inflammation regulates induction or suppression of some metabolic enzymes of sex steroid hormone

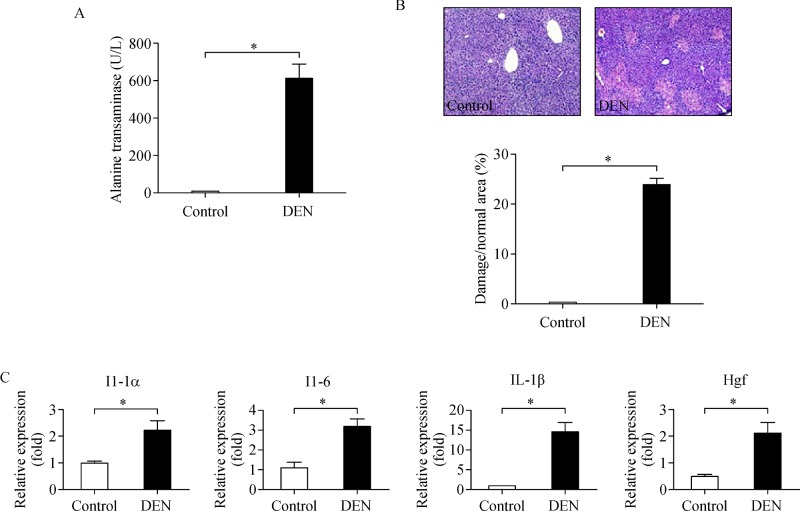

To investigate the role of inflammation in synthesis and metabolism of sex steroids, we treated mice with DEN (100 mg/kg) for 48 hours, and then analyzed various enzymes in mouse liver. Mice were found to exhibit significantly higher DEN-induced hepatic injury 48-hour post-treatment, as determined by increased serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels (Fig. 1A) and liver damage (Fig. 1B). ALT is found in plasma and is commonly measured clinically as a biomarker for determining liver health and damage[15–16]. We observed higher ALT levels (609.1 U/L) in the plasma when compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated (10.2 U/L) control livers (Fig. 1A). In response to acute DEN treatment, WT mice were also found to have significantly elevated hepatic expression levels of the genesIl-1α, Il-6, Il-1β, and Hgf encoding the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), respectively (Fig. 1C).

Fig.1. Influence of inflammation on sex steroid metabolic enzyme in the liver.

A: Increased circulating ALT levels in mice 48 h post-DEN injection in 6-wk-old mice. Values represent means±SEM. *P 0.05. B: Representative histological analyses of control and DEN-treated mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining is shown. C: mRNA level of Il-1α, Il-6, Il-1β, and Hgf. Values represent means±SEM. *P 0.05 (n = 5-8).

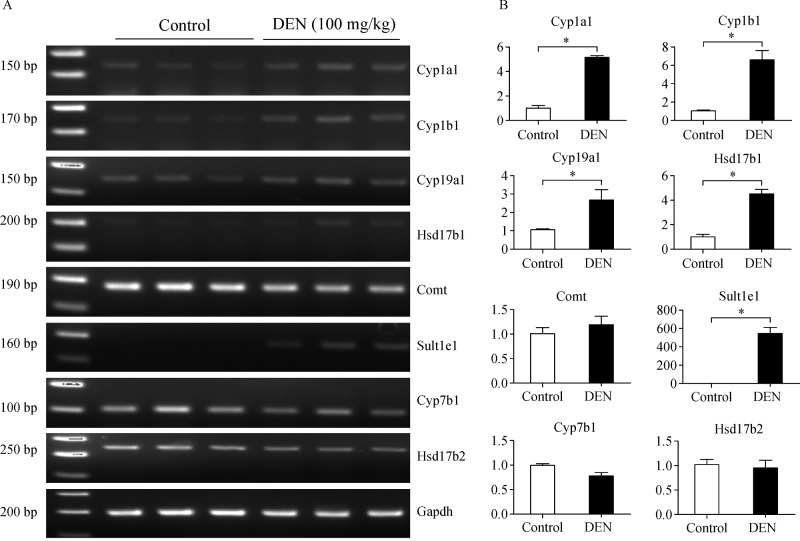

To assess the expression levels of mRNA that encode enzymes involved in synthesis and metabolism of sex hormones, we performed RT-PCR ( Fig. 2A). Using a real-time RT-PCR, we observed increases (5-fold) in Cyp1a1 mRNA level in the DEN-treated wild type (WT) livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, we observed increases (6.5-fold) in Cyp1b1 mRNA level in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers. Moreover, we observed increases (3-fold and 4.5-fold) inCyp19a1 and Hsd17b1, respectively, mRNA level in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers (Fig. 2B). Although expression of Comt1 mRNA remained unaltered in the DEN-treated WT liver compared with that in the control liver, we observed robust increases (544-fold) inSult1e1 mRNA level in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, we observed decreases (0.78-fold) in Cyp7b1 mRNA level in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers, and there was no significant difference in the expression level of Hsd17b2 between both groups.GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control.

Fig.2. Influence of inflammation on sex steroid metabolic enzyme in liver.

For acute inflammation, 6-week-old mice were administered DEN (100 mg/kg bodyweight) in a 0.9% saline solution, and livers were isolated at 48 h. Using a quantitative RT-PCR (A) and a real-time RTPCR (B), Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, Cyp19a1, Hsd17b1, Comt1, Sult1e1, Cyp7b1, Hsd17b2 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Gapdh mRNA was used as in internal control. Values represent means±SEM. *P 0.05 (n = 5-8).

Inflammatory response enhances metabolic enzymes of sex steroid hormones

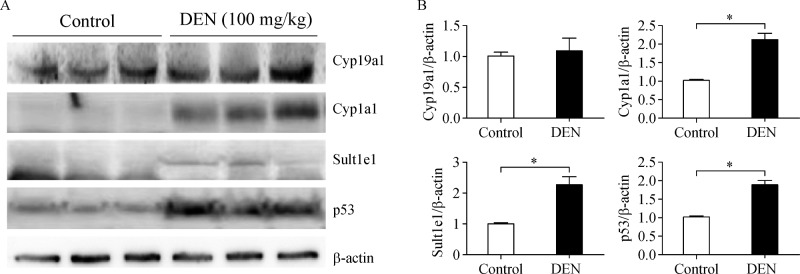

To assess the expression levels of enzyme proteins involved in synthesis and metabolism of sex hormones, we performed Western blotting (Fig. 3A). First, we confirmed the induction of p53 in the DEN-treated livers, which is direct evidence indicating DNA damage[17]. Mice were found to exhibit significantly higher DEN-induced DNA damage (1.87-fold) 48 hours post-treatment, as determined by p53 stabilization (Fig. 3B). Although the levels of the protein Cyp19a1 did not increase in the DEN-treated livers, we observed increases (2.10-fold) in Cyp1a1 enzyme activity in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers. Moreover, we observed robust increases (2.23-fold) in Sult1e1 enzyme activity in the DEN-treated WT livers compared to the corresponding vehicle-treated control livers.

Fig.3. Inflammation influences the cellular metabolic enzymes related with sex steroid.

A: The levels of metabolic enzymes in the liver lysates were assessed by Western blotting. For these experiments, 40 mg samples of protein extracts were analyzed, and β-actin was also examined as internal cellular controls. B: Relative amounts of Cyp19a1, Cyp1a1, Sult1e1, and p53 in extracts were evaluated based on quadruplicate Western blot analysis, as illustrated in above. Values represent means±SEM. *P 0.05 (n = 5-8).

Discussion

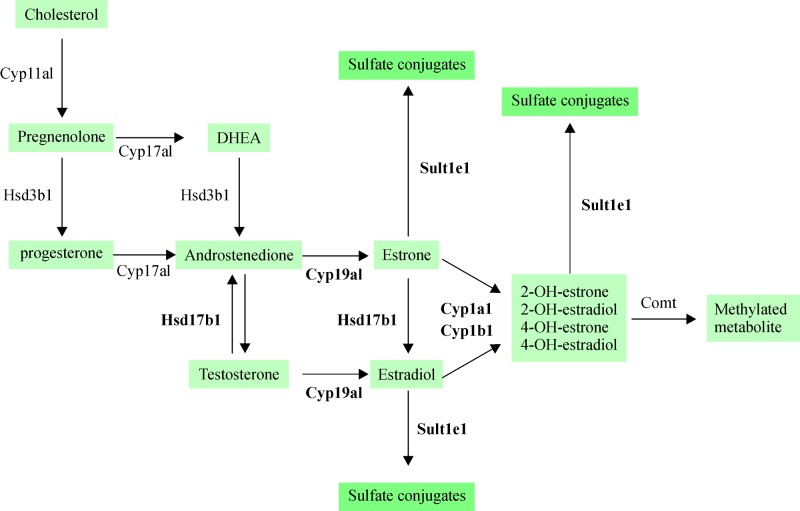

Our study showed that the expression levels of Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, Cyp19a1, and Hsd17b1 mRNA were upregulated in the DEN-treated group compared to the control group. Moreover, the proportion of increased expression level was similar for all four enzymes. In addition, Comt1 mRNA was also upregulated in the DEN-treated group compared to the control group. However, the level of fold change was significantly low than that of the former enzymes. Because the level of upregulation in Comt1 was significantly lower than that of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1, the level of intracellular 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol may be significantly high. In the liver, approximately 80% of estradiol is biotransformed to 2-hydroxyestradiol and 20% to 4-hydroxyestradiol[18]. Cyp1a1, Cyp1a2, and Cyp3a4 exhibit catalytic activity dominantly for 2-hydroxylation rather than 4-hydroxylation of estradiol[19]. In this study, we observed increased activity of Cyp1A1 in the DEN-treated livers compared to that in the control-treated livers using both qRT-PCR and western blotting. Consequently, in the liver tissue of the DEN-treated groups, conversion of androstenedione and testosterone to estradiol may be promoted, with possible subsequent conversion of estradiol to 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol (Fig. 4). Recently, it has been demonstrated that obesity-related inflammation induces aromatase expression, indicating that pro-inflammatory mediators contribute toward upregulated estrogen biosynthesis[20]. However, it should be noted that the regulation of Cyp19a1 expression is unclear, and it is necessary to define its role in the alteration of inflammation. Although expression of the aromatase enzyme cyp19a1 remained unchanged as demonstrated by Western blotting, we confirmed the increase of cyp19a1 mRNA expression in DEN-treated WT livers. In contrast, Cyp1b1 exhibits catalytic activity specifically for the 4-hydroxylation of estradiol[19] and is primarily expressed in estrogen-target tissues, including the mammary, ovary, and uterus rather than liver[21–23]. Although the 4-hydroxyestradiols formed by Cyp1B1 are unstable, they generate free radicals via the redox cycle corresponding to semiquinone and quinone forms and precipitate the damaged DNA[24–25]. In contrast to 4-hydroxyestradiol, 2-hydroxyestradiol formed by Cyp1A1 is not carcinogenic, and it may also undergo a metabolic redox cycle to generate free radicals and reactive semiquinone/quinone intermediates[26–27]. Because 2-hydroxyestradiol is methylated by Comt1 at a faster rate than 4-hydroxyestradiol, free radicals are not easily generated[28]. This flow of gene expression possibly suggests promoted metabolism to produce 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol to inactivate estradiol that increases cell proliferation and, therefore, contribute to inflammatory reaction. However, this flow of gene expression may also suggest increased levels of intracellular 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol because 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol exhibit inhibitory effect on cell proliferation. Furthermore, increased Cyp19a1 and Hsd17b1 levels may support the possibility that 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol regulates inhibition of cell proliferation rather than reducing estradiol.

Fig.4. Synthesis and metabolism of sex hormones in living organisms.

The gray boxes indicates from cholesterol to sex steroid hormone and metabolites. Arrows are the following steroidogenic enzymes: Cyp11a1 (20, 22-desmolase), Cyp17a1, (17,22-desmolase), Hsd17b1 (17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), Hsd3b1(3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), Cyp19a1(Aromatase), Cyp1a1 or Cyp1b1 (aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase), Sult1e1 (Sulfotransferase), Comt1 (O-methylated to monomethoxy).

Of interest, substantial difference existed in the relative abundance of Sult1e1 mRNA between the control and DEN-treated livers. Furthermore, increased Sult1e1 levels may promote conversion of estrone and estradiol to estrone-sulfate and estradiol-sulfate, respectively, in the nanomolar range[29]. As described above, Sult1e1 could convert the generated 2- or 4-hydroxyestrone and 2- or 4-hydroxyestradiol to sulfate conjugates (Fig. 4). Sult1e1 is expressed in the liver[30] and is able to catalyze the sulfation of physiologic concentrations of estrogens[31]. Although steroid sulfation still contributes significantly to control the levels of biologically active hormone in target tissues, it functions as a reservoir after the hydrolysis of sulfate conjugates by sulfatases[32] and helps in renal excretion of steroids[33].

Therefore, to determine the influence of inflammation on metabolism of sex hormones, we subjected metabolic enzymes to additional physiologic inflammatory response in vivo to study its biochemical properties on the liver. The results of the present study support the assumption that inflammatory response sequesters sulfate conjugates from endogenous steroid hormones and may modulate access to their receptors in the whole body.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research fund of Chungnam National University.

Contributor Information

Sang R. Lee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

Seung-yeon Lee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea..

Sang-yun Kim, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea..

Si-yun Ryu, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea..

Bae-kuen Park, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea..

Eui-Ju Hong, Email: ejhong@cnu.ac.kr., College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea..

References

- 1. Kristensen VN, Borresen-Dale AL. Molecular epidemiology of breast cancer: genetic variation in steroid hormone metabolism[J].Mutat Res, 2000, 462(2-3): 323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durocher F, Sanchez R, Ricketts ML, et al. Characterization of the guinea pig 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Delta5-Delta4-isomerase expressed in the adrenal gland and gonads[J].J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2005, 97(3): 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Neill JS, Miller WR. Aromatase activity in breast adipose tissue from women with benign and malignant breast diseases[J].Br J Cancer, 1987, 56(5): 601–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martucci CP, Fishman J. P450 enzymes of estrogen metabolism[J].Pharmacol Ther, 1993, 57(2-3): 237–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ritter JK, Sheen YY, Owens IS. Cloning and expression of human liver UDP-glucuronosyltransferase in COS-1 cells. 3,4-catechol estrogens and estriol as primary substrates[J].J Biol Chem, 1990, 265(14): 7900–7906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernández JS, Watson RW, Wood TC, et al. Sulfation of estrone and 17 beta-estradiol in human liver. Catalysis by thermostable phenol sulfotransferase and by dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase[J].Drug Metab Dispos, 1992, 20(3): 413–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ball P, Knuppen R. Catecholoestrogens (2-and 4-hydroxyoestrogens): chemistry, biogenesis, metabolism, occurrence and physiological significance[J].Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh), 1980, 232: 1–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee AJ, Kosh JW, Conney AH, et al. Characterization of the NADPH-dependent metabolism of 17beta-estradiol to multiple metabolites by human liver microsomes and selectively expressed human cytochrome P450 3A4 and 3A5[J].J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2001, 298(2): 420–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee AJ, Mills LH, Kosh JW, et al. NADPH-dependent metabolism of estrone by human liver microsomes[J].J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2002, 300(3): 838–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lord RS, Bongiovanni B, Bralley JA. Estrogen metabolism and the diet-cancer connection: rationale for assessing the ratio of urinary hydroxylated estrogen metabolites[J].Altern Med Rev, 2002, 7(2): 112–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song WC. Biochemistry and reproductive endocrinology of estrogen sulfotransferase[J].Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2001, 948: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pasqualini JR. Enzymes involved in the formation and transformation of steroid hormones in the fetal and placental compartments[J].J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2005, 97(5): 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmidt M, Naumann H, Weidler C, et al. Inflammation and sex hormone metabolism[J].Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006, 1069: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shiau HJ, Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Reynolds MA. Influence of sex steroids on inflammation and bone metabolism[J].Periodontol 2000, 2014, 64(1): 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lv J, Xiao Q, Chen Y, et al. Effects of magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate on AST, ALT, and serum levels of Th1 cytokines in patients with allo-HSCT[J].Int Immunopharmacol, 2017, 46: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sozen H, Celik OI, Cetin ES, et al. Evaluation of the protective effect of silibinin in rats with liver damage caused by itraconazole[J].Cell Biochem Biophys, 2015, 71(2): 1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyun SY, Jang YJ. p53 activates G 1 checkpoint following DNA damage by doxorubicin during transient mitotic arrest[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(7): 4804–4815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weisz J, Bui QD, Roy D, et al. Elevated 4-hydroxylation of estradiol by hamster kidney microsomes: a potential pathway of metabolic activation of estrogens[J].Endocrinology, 1992, 131(2): 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee AJ, Cai MX, Thomas PE, et al. Characterization of the oxidative metabolites of 17beta-estradiol and estrone formed by 15 selectively expressed human cytochrome p450 isoforms[J].Endocrinology, 2003, 144(8): 3382–3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimodaira M, Nakayama T, Sato I, et al. Estrogen synthesis genes CYP19A1, HSD3B1, and HSD3B2 in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy[J].Endocrine, 2012, 42(3): 700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shimada T, Hayes CL, Yamazaki H, et al. Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P-450 1B1[J].Cancer Res, 1996, 56(13): 2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hakkola J, Pasanen M, Pelkonen O, et al. Expression of CYP1B1 in human adult and fetal tissues and differential inducibility of CYP1B1 and CYP1A1 by Ah receptor ligands in human placenta and cultured cells[J].Carcinogenesis, 1997, 18(2): 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tang YM, Chen GF, Thompson PA, et al. Development of an antipeptide antibody that binds to the C-terminal region of human CYP1B1[J].Drug Metab Dispos, 1999, 27(2): 274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nutter LM, Ngo EO, Abul-Hajj YJ. Characterization of DNA damage induced by 3,4-estrone-o-quinone in human cells[J].J Biol Chem, 1991, 266(25): 16380–16386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nutter LM, Wu YY, Ngo EO, et al. An o-quinone form of estrogen produces free radicals in human breast cancer cells: correlation with DNA damage[J].Chem Res Toxicol, 1994, 7(1): 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henderson BE, Ross RK, Pike MC. Toward the primary prevention of cancer[J].Science, 1991, 254(5035): 1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li JJ, Li SA, Oberley TD, et al. Carcinogenic activities of various steroidal and nonsteroidal estrogens in the hamster kidney: relation to hormonal activity and cell proliferation[J].Cancer Res, 1995, 55(19): 4347–4351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emons G, Merriam GR, Pfeiffer D, et al. Metabolism of exogenous 4- and 2-hydroxyestradiol in the human male[J].J Steroid Biochem, 1987, 28(5): 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adjei AA, Weinshilboum RM. Catecholestrogen sulfation: possible role in carcinogenesis[J].Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2002, 292(2): 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aksoy IA, Wood TC, Weinshilboum R. Human liver estrogen sulfotransferase: identification by cDNA cloning and expression[J].Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1994, 200(3): 1621–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yong M, Schwartz SM, Atkinson C, et al. Associations between polymorphisms in glucuronidation and sulfation enzymes and sex steroid concentrations in premenopausal women in the United States[J].J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2011, 124(1-2): 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hanson SR, Best MD, Wong CH. Sulfatases: structure, mechanism, biological activity, inhibition, and synthetic utility[J].Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2004, 43(43): 5736–5763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strott CA. Steroid sulfotransferases[J].Endocr Rev, 1996, 17(6): 670–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]