Abstract

Unbalanced brain serotonin (5-HT) levels have implications in various behavioral abnormalities and neuropsychiatric disorders. The biosynthesis of neuronal 5-HT is regulated by the rate-limiting enzyme, tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TPH2). In the present study, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) system was used to target theTph2 gene in Bama mini pig fetal fibroblasts. It was found that CRISPR/Cas9 targeting efficiency could be as high as 61.5%, and the biallelic mutation efficiency reached at 38.5%. The biallelic modified colonies were used as donors for somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) and 10Tph2 targeted piglets were successfully generated. These Tph2 KO piglets were viable and appeared normal at the birth. However, their central 5-HT levels were dramatically reduced, and their survival and growth rates were impaired before weaning. TheseTph2 KO pigs are valuable large-animal models for studies of 5-HT deficiency induced behavior abnomality.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene, serotonin, Bama mini pigs

Introduction

The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), an important extracellular signaling molecule, has been implicated in a broad range of physiological functions in the central and peripheral nervous systems. In vertebrates, 2 tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) isoforms, TPH1 and TPH2 encoded by 2 distinct genes, are responsible for the rate-limiting step of the biosynthesis of 5-HT[1–2]. It has been well documented that TPH1 and TPH2 differ in terms of their spatial distribution. TPH1 is extremely abundant in the gut and pineal gland, accounting for the main source of circulating 5-HT, whereas TPH2 is specifically expressed in serotonergic neurons of the raphe nuclei of the brainstem, responsible for the synthesis of central 5-HT[3–11]. Because genetic variation and functional mutations in the human Tph2 gene have been shown to be associated with cognition and emotional regulation as well as neuropsychiatric disease and behavioral abnormalities[12–16], Tph2 has drawn increasing attention in scientific community.

During the past decade, the ensuing genetically modified Tph2 mouse models in which the biosynthesis of neuronal 5-HT is selectively ablated in the brain have been generated, and these have provided considerable insight into understanding various neurobehavioral processes regulated by serotonergic neurotransmiss-ion[11,17–21]. However, these rodent models cannot fully recapitulate human 5-HT deficiency properties because their physiology and gene expression differ from those of humans, and studies usingTph2-deficient large animal models have not been reported[10,22–23]. Currently, pigs are extensively used as a large-animal model for biomedical research because they share many similarities with humans in terms of anatomy, physiology, immunology, compared to rodents[24–26]. Pigs are less expensive to procure and involve fewer ethical issues than other large animals, such as non-human primates. Pigs also have advantages over rodent models for cognition and behavior studies in that they have high-level of emotional and cognitive abilities, and their anatomical brain structures are similar to those of humans[27–29].

Recently, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) system has significantly improved gene targeting efficiency and has been extensively used to generate genetically modified animal models in various species, including mice[30], rabbits[31], sheep[32], and pigs[33–34]. In this study, Tph2-/- piglets were successfully generated by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system combined with somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) technology, which could be utilized to elucidate the physiological function ofTph2 in a further study.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Nanjing Medical University. All pigs were housed in Nanjing Medical University animal facilities, and standard animal husbandry protocols were followed.

Targeting vector construction

Targeting sgRNA 1 and sgRNA 2 for the Tph2 coding region were designed using online tools (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and synthesized by Genscript Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Oligos of sgRNAs were annealed and sub-cloned in to BbsI-digested pX330 (addgene #423230) plasmid, respectively. The resulting targeting vectors for Tph2 were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Generation of Tph2 targeted cell lines

Primary fibroblasts (PFFs) derived from 34 days old Bama mini-pig fetuses were cultured in medium consisting of high glucose DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 15% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1 × Penn/Strep solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). 1 mg Tph2 targeting vector was introduced into PFFs followed the methods described previously[35]. The electroporated cells were maintained with G418 at 800 mg/mL thereafter. Single colonies were picked and cultured in 48-well plates. Confluent wells were treated with 0.05% trypsin and re-suspended using 300 mL culture medium. Aliquot cells were plated in a 12-well plate, and the remaining cells were lysed for Tph2 genotyping. The primers were: 5′-gattgggccgtcaaatcctg-3′ and 5′-ctacctggtcagtgagcctc-3′. PCR conditions were 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and finally 72°C for 7 minutes. The PCR products of each colony were purified using a NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and then cloned into pMD18-T vector (Takara Clontech, Tokyo, Japan) for sequencing.

Production of mutant piglets

SCNT procedure was described by Chen et al.[35]. Briefly, oocytes were collected and cultured for 42–44 hours. The cumulus cells and nuclei of in vitro matured oocytes were then removed. The mutant cell lines were pooled as nuclear donor cell to be injected into the perivitelline space of the oocytes. Then, the electrically activated reconstructed embryos were cultured in embryo culture medium at 38°C for 3 days. About 260 blastocysts were transplanted into the uteruses of the surrogate pigs. The genomic DNA isolated from the ear biopsy of the neonates was used to assess mutagenesis at the targetedTph2 site by sequencing.

T7E1 cleavage assay

Fibroblasts transfected with Cas9 plasmids of different sgRNAs (as described above) were cultured for 48 hours. Genomic DNA was isolated and PCR was performed to amplify the genomic region spanning the CRISPR target sites forTph2. The T7E1 cleavage assay was performed using an EnGen® Mutation Detection Kit (NEB, Beverly, MA, USA) as previously described[32].

Histology and immunofluorescence analysis

The tissues of brainstem from Tph2-/- pigs and wild-type pigs were fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. The entire tissue was then dissected, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at 5 mm. Sections deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or immune-stained overnight at 4°C with anti-TPH2 polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Images were obtained using a Digital Sight DS-Ri1 camera on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope.

Western blot analysis

Brainstems from euthanized piglets were prepared by homogenization in the presence of protease inhibitors (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and centrifuged to remove residual debris. The samples were heat-denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes with 5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and fractionated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH (HRP-60004, Proteintech, Manchester, UK) was used as a standard control protein. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% skim milk powder. Primary antibodies used Anti-TPH2 antibody (ab121013, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), which use a concentration of 2 mg/mL.

Results

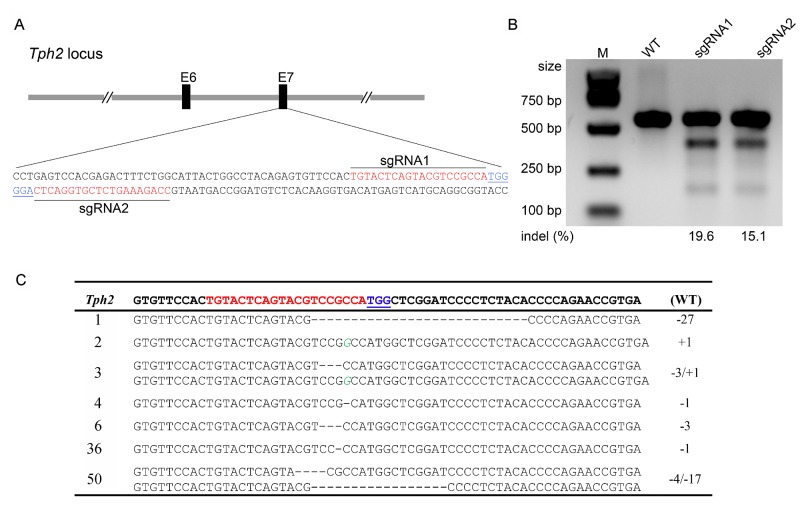

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Tph2 gene targeting in PFFs

To knock out the Tph2 gene in pigs, 2 sgRNAs targeted the exon 7 of Tph2 were designed following previously described procedures[32]. The precise target sites are shown in Fig. 1A. To test their cleavage efficacy, these 2 sgRNAs were cloned into pX330 vector and transfected into PFFs derived from 35-day-old Bama mini fetuses. Genomic DNA was harvested from transfected PFFs after 48 h. PCR amplicons spanning theTph2 target region were subjected to T7 Endonuclease I assay followed by gel electrophoresis analysis. The results showed that both sgRNAs could induce indels in theTph2 target region, while sgRNA1 shows slightly higher cleavage efficiency (19.2%) than sgRNA2 (15.1%) (Fig. 1B). In this way, sgRNA1 was chosen for subsequent Tph2 gene targeting.

Fig.1. CRISPR/Cas9 mediates Tph2 gene targeting in PFFs.

A: Schematic of Cas9/sgRNAs targeting sites of pig Tph2 locus. The sgRNA targeting sequences are highlighted in red, and the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) sequences are highlighted in blue and underlined. B: T7E1 assay of PCR products spanning the Tph2 targeting region. M: DNA marker; WT: PCR product of wild-type; sgRNA1 and sgRNA2: PCR products of PFFs transfected with sgRNA1 and sgRNA2, respectively. C: Genotypes of Tph2 biallelic modified colonies. "-": deletion; "+": insertion; italic green letters denote inserted base pairs.

To establish Tph2mutation cell lines, the Cas9-sgRNA1 targeting vector and a TD-tomato plasmid containing a neomycin resistance (Neo) gene were co-transfected into an early passage of primary PFFs. Cells were maintained with G418 thereafter until single resistant colonies were formed. Genotyping analysis of each colony was performed using TA-cloning and Sanger sequencing. The results indicated that 12 colonies had monoallelic modifications in theTph2 targeting region and 20 had biallelic modifications (Table 1). About 38.5% of the cell colonies had biallelic mutations (Table 1). Genotypes of Tph2 biallelic modified colonies are shown in Fig. 1C.

Tab.1.

Summary of mutant colonies of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Tph2 gene targeting

| Experiment | Monoallelic mutation | Biallelic mutation | Indel-positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5/27 | 9/27 | 14/27 |

| 2 | 7/25 | 11/25 | 18/25 |

| Total | 12/52 (23.1%) | 20/52 (38.5%) | 32/52 (61.5%) |

Mutant colonies/total colonies were tested in 2 independent tests.

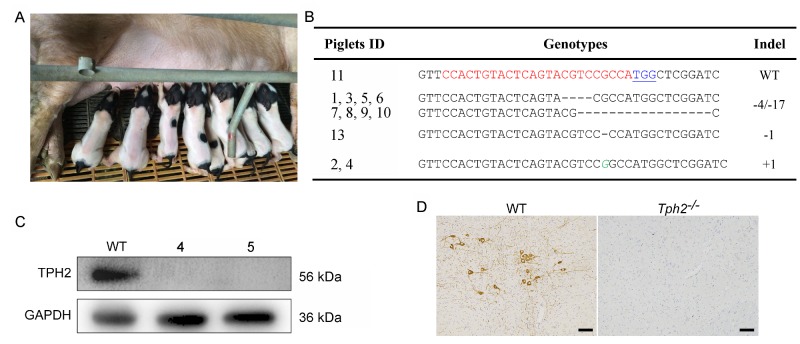

Production of Tph2-/- pigs by SCNT

To produce Tph2 KO piglets, PFFs colonies with biallelic mutations were mixed as donor cells for SCNT. Totally, 1,800 reconstructed embryos were transferred into 7 recipient gilts. Each recipient was monitored by B-ultrasonic examination about one mouth after operation, and 2 pregnant gilts were discovered to be expecting, showing a pregnancy rate of 28.6% (Table 2). The 2 recipients were maintained to term and gave birth to 12 live-born piglets without displaying any obvious developmental defects or differences from wild-type neonates (Fig. 2A). Genotyping results showed all piglets except No. 11 to be biallelic Tph2 mutants. Piglet No. 11 was determined to be a Tph2 wild type, probably due to contamination of colonies with a few wild type PFFs. Eight piglets ( No. 1, No. 3, No. 5, No. 6, No. 7, No. 8, No. 9, and No. 10) carried a-4/-17 bp deletion derived from No. 50 donor cells, 2 piglets ( No. 2 and No. 4) born a+1 bp insertion originate from No. 2 donor cells, and No. 13 piglet contained a-1 bp deletion derived from No. 4 colony, respectively (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2B).

Fig.2. Generation of Tph2 gene targeted piglets via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT).

A: Photograph of newborn cloned piglets carrying Tph2 gene mutation. B: Genotypes of cloned piglets. "-": deletion; "+": insertion; italic green letters denote inserted base pairs. C: Representative Western blot of TPH2 protein of cloned piglets and wild type control. D: Representative images of TPH2 immunohistochemistry on brainstem sections. Scale bar is 50 μm.

Tab.2.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer results for the generation of knockout cloned pigs

| Recipient | Donor cells | Transferred embryos | Pregnancy | Newborn piglets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31, 2 | 280 | NO | - | |

| 2 | 2, 50 | 255 | YES | 10 | |

| 3 | 41, 4 | 260 | NO | - | |

| 4 | 46, 2, 41 | 265 | NO | - | |

| 5 | 12, 36 | 255 | YES | 2 | |

| 6 | 2, 3 1 | 245 | NO | - | |

| 7 | 4, 12 | 260 | NO | - | |

| Total | 1,820 | 28.6% | 12 |

To determine the TPH2 protein expression level of the gene targeted piglets, Western blot analysis was carried out using the whole protein extracted from brain stem ofTph2 targeted piglets and age-matched wild type controls. As shown in Fig. 2C, unlike in the WT control, the expression of TPH2 protein was undetectable in Tph2 targeted piglets (Fig. 2C). To further characterize TPH2 expression, immunohistochemistry was conducted on brainstem sections. Consistent with the Western blot results,Tph2 signal was observed only in WT and not in the Tph2 KO piglets (Fig. 2D). These results confirmed that the Tph2 targeted piglets generated in this study were authentic Tph2 KO animals.

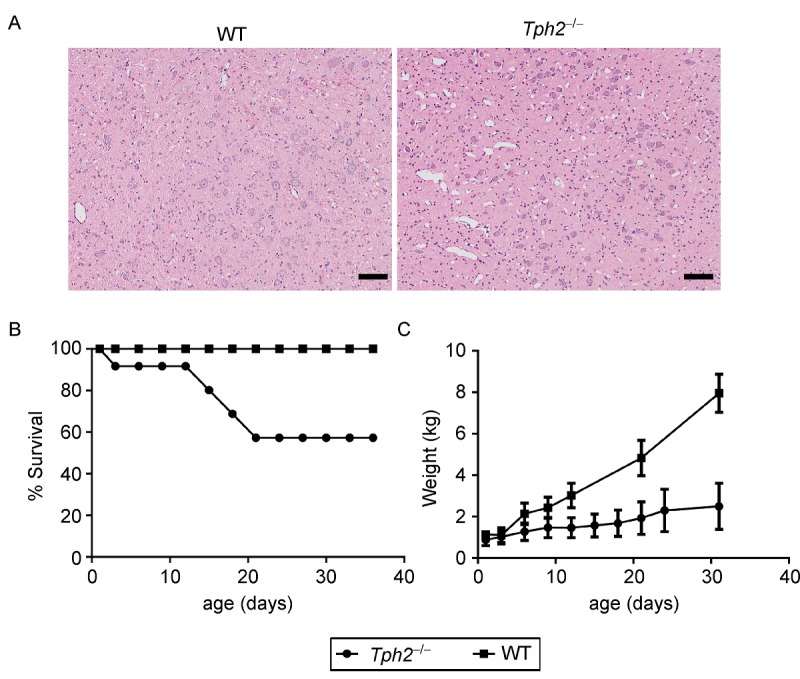

Survival and body weight of Tph2-/- piglets were reduced during lactation

To assess the developmental consequence of Tph2 KO in piglets, brainstem sections were stained using the hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) method. The results showed no obvious difference in the structures of neuronal cells betweenTph2 KO and WT pigs, indicating that Tph2 KO may have little influence on formation of the organizational structure of brainstem (Fig. 3A). However, Tph2 KO piglets showed a decrease in survival rate (36.4%) compared with WT piglets from birth to weaning (Fig. 3B). Tph2 KO piglets were also shown significantly less body weight than age-matched WT controls before weaning (Fig. 3C). These data indicated that lack of central 5-HT may have a detrimental effect on piglet breast feeding behavior which resulted in a much less body weight and lower survival rate ofTph2 KO piglets before weaning. Extensive well-controlled behavior studies will be conducted once more Tph2 KO piglets are produced.

Fig.3. Survival and body weight of the Tph2-/- piglets were reduced before weaning.

A: Representative H&E images of organizational structure of neuronal cells of the Tph2-/- piglets and WTcontrol. Scale bar is 50 μm. B: The survival curve of Tph2-/- and WT piglets. Tph2-/- pigs showed a higher mortality before weaning than in WT. C: Body weight of Tph2-/- and WT piglets. Data are presented as the mean ±SEM. WT, n =4; Tph2-/-, n = 10 at birth, n = 6 at the endpoint.

Off-target analysis

Although the CRISPR/Cas9 system has the advantage of high gene targeting efficiency in pigs, the undesired off-target effects are still a major concern[34,36]. To determine whether off-target mutagenesis occurred in the Tph2 KO piglets, 20 potential off-target sites (OTSs) for sgRNA1 were founded by using the CRISPR design tool (http://crispr.mit.edu/). The sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1, available online. Five OTSs with high score were chosen for PCR amplification using genomic DNA isolated from Tph2 KO piglets and WT controls. The primers used to amplify the OTSs are listed in Table 3. Sanger sequencing of the PCR amplicons showed that none of the sequencing reads exhibited mutations, indicating that there had been no off-target effects at these OTSs in Tph2 KO piglets.

Tab.3.

Primers for amplifying off-target sites

| Primer | Sequence (5′- 3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| OTS1 for | CCTTTGATTGAAGCTGTGTGAA | 307 |

| OTS1 rev | CAATGTCCTCTGACCGACTG | |

| OTS2 for | AATCACTCAGAACAGAGCCAAG | 303 |

| OTS2 rev | ATCCTCCTTTACGCCAGGTC | |

| OTS3 for | GAAGATGGACATTGCCAGGAC | 314 |

| OTS3 rev | CGCCAACAAAGTAAACCAAACT | |

| OTS4 for | TGTGCTGGACATATACTTGAGA | 306 |

| OTS4 rev | GGAGGATTCAGAAGAAGGTGAT | |

| OTS5 for | ACACCTCCTAACCCAAGTGAG | 338 |

| OTS5rev | CACAAGTAACCAGAGCCACAG |

Discussion

In the present study, Tph2 targeted pigs were successfully generated by combination of the CRISPR/Cas9 system and SCNT technology in which the TPH2 was totally depleted in the brain. The gene targeting efficiency of the sgRNA/Cas9 in PFFs reached as high as 61.5% (Table 1), which was much higher than that of the homologous-recombination-basedTph2 targeting in mice[17,21]. TheTph2 targeting efficiency in PFFs in this study is 61.5% with 38.5% biallelic mutation, which is higher than that ofIgM reported by Chen et al. [35] (53.3% targeting efficiency with 13.3% biallelic mutation). This is probably due to sgRNAs specifically forIgM andTph2 are of different cleavage efficiency. In addition, 10 homozygous Tph2-/- pigs were generated by just 1 round of SCNT. In this way, the high efficiency and ease of the Cas9/sgRNA system can greatly facilitate the rapid production of KO pig models.

Although off-target effects are a major concern of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting system[36–38], no off-target event was detected in Tph2-/- piglets produced in the present study. However, off-target mutagenesis may occur in the cloned Tph2-/- piglets because the Sus scrofa genome sequence is incomplete, which has hampered comprehensive searches for off-target events. To produce theTph2-targeted piglets, the several knockout PFF colonies were mixed for SCNT procedure and the reconstructed embryos were transferred into a single recipient. Interestingly, results showed that the number of piglets developed from a particularTph2 KO cell line cell (No. 50) was markedly higher than that of the other cell colonies (Table 4). These results indicated that either the No. 50 cell colony had higher competency or other cell colonies might contain undesired off-target mutations that could impair the integrity of the cell genome and impair its development during embryo manipulation. For this reason, transferring pooled embryos derived from multiple cell lines of different clonability into a single surrogate could be a practical strategy to increase the chance to achieve cloned gene-targeted pigs.

Tab.4.

Summary of Tph2-/- pigs

| Piglets ID | Birth length (cm) | Birth weight (g) | Health status | Donor cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | 563 | Alive | 50 |

| 2 | 22.5 | 916 | Dead on day 18 | 2 |

| 3 | 20 | 604 | Dead on day 21 | 50 |

| 4 | 22.5 | 897 | Dead on day 3 | 2 |

| 5 | 23 | 983 | Alive | 50 |

| 6 | 24 | 1,018 | Alive | 50 |

| 7 | 21.5 | 938 | Alive | 50 |

| 8 | 23.5 | 964 | Alive | 50 |

| 9 | 23.5 | 1,020 | Alive | 50 |

| 10 | 22 | 893 | Dead on day 15 | 50 |

| 11 | 23 | 1,140 | Alive | WT |

| 12 | Mummy fetus | |||

| 13 | 20 | 1,420 | Alive | 36 |

Consistent with Tph2 KO mice models[17], the raphe serotonergic neurons in Tph2-disrupted piglets are completely devoid of 5-HT immunoreactivity, but no gross brain morphological abnormalities occur. These results provide evidence for the conclusion that TPH2 is solely responsible for raphe neuron 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT may not be indispensable to the development and maintenance of raphe serotonergic neurons. Moreover, reduction of the body weight and the postnatal survival shown in theTph2-/- piglets before weaning are consistent with observations made in 5-HT depleted Tph2 knockout mice[19,21], indicating 5-HT plays a similar role in neonatal viability and growth rate across species. Dysregulation of 5-HT has long been thought to induce various mental conditions including depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, autism, and schizophrenia[12–16]. Behavioral abnormalities were not evaluated in these Tph2-/- pigs because of the scope of this study and the long time required for such experiments. However, amplification of the Tph2-/- pigs by cross-breeding for these experiments are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

In summary, these Tph2-/- piglets are a valuable model that will be useful for investigation of the developmental and functional consequences of altered brain-specific 5-HT level and its role in cognition, emotional regulation, and neuropsychiatric disease risk.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570402), a grant from the Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Xenotransplantation (BM2012116), and grants from the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, the Fund for High Level Medical Discipline Construction of Shenzhen (No. 2016031638), and the Shenzhen Foundation of Science and Technology (No. JCYJ20160229204849-975 and GCZX2015043017281705), and grant from the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB55-9200).

Contributor Information

Rong-Feng Li, Email: lirongfeng@njmu.edu.cn.

Yi Rao, Email: yrao@ pku.edu.cn.

Yi-Fan Dai, Email: daiyifan@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Walther DJ, Bader M. A unique central tryptophan hydroxylase isoform[J].Biochem Pharmacol, 2003, 66(9): 1673–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, et al. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform[J].Science, 2003, 299(5603): 76–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Côté F, Thévenot E, Fligny C, et al. Disruption of the nonneuronal tph1 gene demonstrates the importance of peripheral serotonin in cardiac function[J].Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003, 100(23): 13525–13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Malek ZS, Dardente H, Pevet P, et al. Tissue-specific expression of tryptophan hydroxylase mRNAs in the rat midbrain: anatomical evidence and daily profiles[J].Eur J Neurosci, 2005, 22(4): 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKinney J, Knappskog PM, Haavik J. Different properties of the central and peripheral forms of human tryptophan hydroxylase[J].J Neurochem, 2005, 92(2): 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura K, Sugawara Y, Sawabe K, et al. Late developmental stage-specific role of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 in brain serotonin levels[J].J Neurosci, 2006, 26(2): 530–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zill P, Büttner A, Eisenmenger W, et al. Analysis of tryptophan hydroxylase I and II mRNA expression in the human brain: a post-mortem study[J].J Psychiatr Res, 2007, 41(1-2): 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abumaria N, Ribic A, Anacker C, et al. Stress upregulates TPH1 but not TPH2 mRNA in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus: identification of two TPH2 mRNA splice variants[J].Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2008, 28(3): 331–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cichon S, Winge I, Mattheisen M, et al. Brain-specific tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2): a functional Pro206Ser substitution and variation in the 5′-region are associated with bipolar affective disorder[J].Hum Mol Genet, 2008, 17(1): 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gutknecht L, Kriegebaum C, Waider J, et al. Spatio-temporal expression of tryptophan hydroxylase isoforms in murine and human brain: convergent data from Tph2 knockout mice[J].Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 2009, 19(4): 266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Migliarini S, Pacini G, Pelosi B, et al. Lack of brain serotonin affects postnatal development and serotonergic neuronal circuitry formation[J].Mol Psychiatry, 2013, 18(10): 1106–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gutknecht L, Jacob C, Strobel A, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene variation influences personality traits and disorders related to emotional dysregulation[J].Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2007, 10(3): 309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leppänen JM, Peltola MJ, Puura K, et al. Serotonin and early cognitive development: variation in the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene is associated with visual attention in 7-month-old infants[J].J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2011, 52(11): 1144–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin CH, Tseng YL, Huang CL, et al. Synergistic effects of COMT and TPH2 on social cognition[J].Psychiatry, 2013, 76(3): 273–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baehne CG, Ehlis AC, Plichta MM, et al. Tph2 gene variants modulate response control processes in adult ADHD patients and healthy individuals[J].Mol Psychiatry, 2009, 14(11): 1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campos SB, Miranda DM, Souza BR, et al. Association study of tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene polymorphisms in bipolar disorder patients with panic disorder comorbidity[J].Psychiatr Genet, 2011, 21(2): 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gutknecht L, Waider J, Kraft S, et al. Deficiency of brain 5-HT synthesis but serotonergic neuron formation in Tph2 knockout mice[J].J Neural Transm (Vienna), 2008, 115(8): 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Savelieva KV, Zhao S, Pogorelov VM, et al. Genetic disruption of both tryptophan hydroxylase genes dramatically reduces serotonin and affects behavior in models sensitive to antidepressants[J].PLoS One, 2008, 3(10): e3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alenina N, Kikic D, Todiras M, et al. Growth retardation and altered autonomic control in mice lacking brain serotonin[J].Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(25): 10332–10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yadav VK, Oury F, Suda N, et al. A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure[J].Cell, 2009, 138(5): 976–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pelosi B, Pratelli M, Migliarini S, et al. Generation of a Tph2 Conditional Knockout Mouse Line for Time- and Tissue-Specific Depletion of Brain Serotonin[J].PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0136422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, et al. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression[J].J Neurochem, 1996, 66(6): 2621–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, et al. , and the Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome[J].Nature, 2002, 420(6915): 520–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aigner B, Renner S, Kessler B, et al. Transgenic pigs as models for translational biomedical research[J].J Mol Med (Berl), 2010, 88(7): 653–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al-Mashhadi RH, Sørensen CB, Kragh PM, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in cloned minipigs created by DNA transposition of a human PCSK9 gain-of-function mutant[J].Sci Transl Med, 2013, 5(166): 166ra1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han K, Liang L, Li L, et al. Generation of Hoxc13 knockout pigs recapitulates human ectodermal dysplasia-9[J].Hum Mol Genet, 2017, 26 (1): 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lind NM, Moustgaard A, Jelsing J, et al. The use of pigs in neuroscience: modeling brain disorders[J].Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2007, 31(5): 728–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. White E, Woolley M, Bienemann A, et al. A robust MRI-compatible system to facilitate highly accurate stereotactic administration of therapeutic agents to targets within the brain of a large animal model[J].J Neurosci Methods, 2011, 195(1): 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adcock SJJ, Martin GM, Walsh CJ. The stress response and exploratory behaviour in Yucatan minipigs (Sus scrofa): Relations to sex and social rank[J].Physiol Behav, 2015, 152(Pt A): 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering[J].Cell, 2013, 153(4): 910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yuan L, Sui T, Chen M, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated GJA8 knockout in rabbits recapitulates human congenital cataracts. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crispo M, Mulet AP, Tesson L, et al. Efficient Generation of Myostatin Knock-Out Sheep Using CRISPR/Cas9 Technology and Microinjection into Zygotes[J].PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0136690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hai T, Teng F, Guo R, et al. One-step generation of knockout pigs by zygote injection of CRISPR/Cas system[J].Cell Res, 2014, 24(3): 372–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou X, Xin J, Fan N, et al. Generation of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-targeted pigs via somatic cell nuclear transfer[J].Cell Mol Life Sci, 2015, 72(6): 1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen F, Wang Y, Yuan Y, et al. Generation of B cell-deficient pigs by highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting[J].J Genet Genomics, 2015, 42(8): 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shen B, Zhang J, Wu H, et al. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting[J].Cell Res, 2013, 23(5): 720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells[J].Nat Biotechnol, 2013, 31(9): 822–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol, 2013, 31(9): 839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]