Abstract

BACKGROUND

Surgeon-performed cervical ultrasound (SUS) and 99Tc-sestamibi scanning (MIBI) are both useful in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT). We sought to determine the relative contributions of SUS and MIBI to accurately predict adenoma location.

STUDY DESIGN

We performed a database review of 516 patients undergoing surgery for PHPT between 2001 and 2010. SUS was performed by 1 of 3 endocrine surgeons. MIBI used 2-hour delayed anterior planar and single-photon emission computerized tomography images. Directed parathyroidectomy was performed with extent of surgery governed by intraoperative parathyroid hormone decline of 50%.

RESULTS

SUS accurately localized adenomas in 87% of patients (342/392), and MIBI correctly identified their locations in 76%, 383/503 (p < 0.001). In patients who underwent SUS first, MIBI provided no additional information in 92% (144/156). In patients who underwent MIBI first, 82% of the time (176/214) SUS was unnecessary (p = 0.015). In 32 patients SUS was falsely negative. The reason for these included gland location in either the deep tracheoesophageal groove (n = 9) or the thyrothymic ligament below the clavicle (n = 5), concurrent thyroid goiter (n = 4), or thyroid cancer (n = 1). In 13 cases, the adenoma was located in a normal ultrasound-accessible location but was missed by the preoperative exam. In the 32 ultrasound false-negative cases, MIBI scans were positive in 21 (66%). Of the 516 patients, 7.6% had multigland disease. Persistent disease occurred in 4 patients (1%) and recurrent disease occurred in 6 (1.2%).

CONCLUSIONS

When performed by experienced surgeons, SUS is more accurate than MIBI for predicting the location of abnormal parathyroids in PHPT patients. For patients facing first-time surgery for PHPT, we now reserve MIBI for patients with unclear or negative SUS.

Parathyroidectomy for nonfamilial primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is curative in >95% of cases. Successful surgery requires removal of all abnormally functioning parathyroid tissue, usually (>85% of the time) involving resection of a single parathyroid adenoma. Less commonly, patients with PHPT may have multiple parathyroid adenomas or hyperplasia that can be identified either visually during standard parathyroidectomy or by a failure of intra-operative parathyroid hormone (PTH) to drop during focused (ie, minimally invasive) parathyroidectomy.

Preoperative imaging of abnormal parathyroid glands in PHPT can improve operative planning and allow the surgeon to perform focused parathyroidectomy. Tc-99m sestamibi scanning (MIBI) was introduced in the 1980s as an imaging tool to identify parathyroid tumors.1 Since then, a substantial body of literature has demonstrated that functional imaging with this molecule is an effective localization study with sensitivity and specificity of 39% to >90% and 94%, respectively.2 This imaging tool has the added advantage of allowing a radioguided approach for both primary and reoperative cases after immediate preoperative injection of radiopharmaceutical. Although other modalities, such as ultrasound, positron-emission tomographic scan, and computerized tomographic (CT) scan, have all been successfully used to image parathyroid tumors in select patients with PHPT, MIBI is the current mainstay of parathyroid imaging.

High resolution (7–10 MHz) cervical ultrasound has been used to image thyroid pathology for some time. This approach has also been successfully applied with significant success to identify abnormal parathyroid glands in patients with PHPT.3 When incorporated into the preoperative evaluation, cervical ultrasound has been shown to be inexpensive, convenient, and have performance similar to MIBI.4 Recently, surgeon-performed ultrasound (SUS) has been increasingly used as a complementary imaging study to MIBI.5,6 When performed by the operating surgeon, SUS becomes increasingly effective owing to the familiarity of the surgical anatomy and the real-time images that can be taken in multiple planes and compared with surrounding anatomy. Importantly, this approach allows the imaging and localization to be performed by the same individual who will be performing the surgery.

Beginning in 2001 surgeon-performed ultrasound of the neck has been a routine element of preoperative evaluation of patients with hyperparathyroidism treated by the 3 endocrine surgeons at our institution. Over time, it has become our experience that ultrasound is the most reliable first preoperative localization study for patients with sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism. To formally evaluate this experience, we performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data on our patients. Our results from >500 patients show that SUS is more accurate than MIBI to identify parathyroid tumors. Furthermore, when performed as the initial imaging study, SUS is the only test needed for the vast majority of patients with PHPT for whom preoperative tumor localization is desired.

METHODS

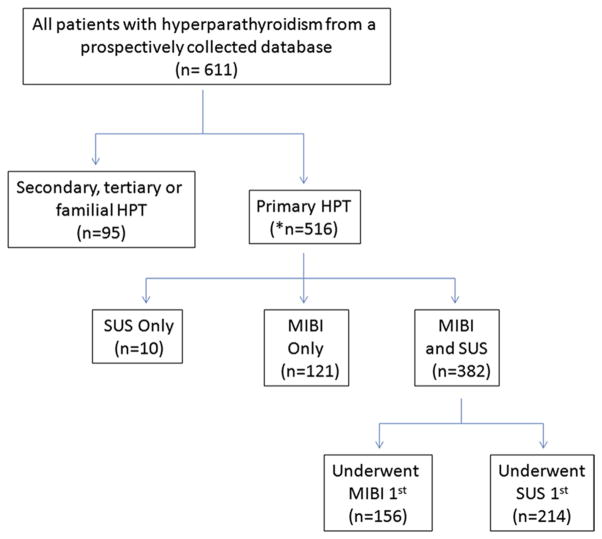

From our institutional parathyroid database of 611 patients with PHPT treated between September 2001 and May 2010 at Duke University Medical Center, we identified 516 patients with sporadic PHPT who had preoperative imaging followed by surgery (Fig. 1). A total of 513 patients had MIBI and/or SUS and complete and evaluable surgical records. Of these patients, 382 had both imaging studies and 370 had verifiable sequence of SUS and MIBI based on dates. There were 156 patients who had SUS first and 214 patients who had MIBI first. Patients in our database that were excluded from this analysis included patients with familial PHPT (n = 14) and patients with secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism (n = 81). This study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study patients. *One patient had missing records, and 2 patients underwent localization with computerized tomographic scan. SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; HPT, hyperparathyroidism.

SUS was performed using the portable Titan or M-Turbo machine (Sonosite, Bothell, WA) with an L38xi 10–5 MHz linear array transducer. The scans were performed and interpreted by 1 of 3 endocrine surgeons, all of whom had formal training through participation in courses sponsored by either the American College of Surgeons or the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology. MIBI was performed in the Division of Nuclear Medicine at Duke University or less frequently at referring institutions. Duke-performed scans used 25 mCi Tc-99m sestamibi administered intravenously. Anterior planar images of the neck and chest were obtained immediately after radiotracer injection, and anterior and anterior-oblique images were obtained of the neck and chest 2 hours after radiopharmaceutical injection. After 2003, immediate and 2-hour delayed anterior planar images were obtained as before with the addition of single-photon emission computerized tomographic and fused noncontrast CT images at the 2-hour timepoint. In general, scans from outside institutions that were positive and were conducted within 6 months of evaluation were not repeated. Outside scans performed earlier than 6 months before surgical evaluation and negative scans were routinely repeated at our institution.

Symptomatic patients and asymptomatic patients meeting National Institutes of Health consensus criteria were offered parathyroidectomy at our institution.7 Directed parathyroidectomy was performed under general anesthesia with or without radioguidance based on patient variables and surgeon preference. The extent of surgery was governed by identification and resection of target parathyroid adenomas followed by intraoperative decline of circulating PTH by ≥50% of the highest baseline value and to a level within the normal range of our assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).8 In cases where multiple parathyroid candidates were identified on preoperative scanning and/or a sufficient PTH decline did not occur, a full 4-gland exploration was conducted. Gland location was defined by the operating surgeon and recorded in the database after confirmation by pathologic records.

Clinical data was recorded in a prospectively maintained database (updated October 2010) maintained by database technicians (Dixit and Webb) in the laboratory of the principal investigator (Olson). Data were analyzed by the first author (Untch) and statistical tests were performed by the authors (Untch, Adam, Bennett) using Graphpad Prism 4 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla CA), Stata 11MP (College Station, TX), and TIBCO Spotfire S+ 8.1 (Somerville, MA). Numeric data is described as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Performance statistics for SUS and MIBI were calculated using the gold standard of parathyroid tumor location determined at surgery. Due to ambiguity between upper and lower gland location based an anatomic variability, imaging results were compared against tumor laterality alone. True positives (TPs) were defined as a pathologically confirmed adenoma/hyperplasia found on the side indicated by the imaging study. False negatives (FNs) were defined as pathologically confirmed adenoma/hyperplasia in patients who had negative imaging. False positives (FPs) were patients that had a positive imaging study but no abnormal gland on the suggested side during neck exploration. Calculation of sensitivity and positive predictive value were based on standard definitions. All patients were assumed to have a parathyroid tumor based on the biochemical definition of hyperparathyroidism (ie, there were no true negative scans). In cases where both SUS and MIBI were performed, concordance and discordance was determined. In these cases, re-review of each scan in the context of the other was not allowed.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study are shown in Table 1. The patients studied included 114 (22%) men and 402 (78%) women. Mean age of the patients was 57.6 years (median 58, range 14 to 87). Mean preoperative serum calcium and PTH levels were 10.9 ± 0.9 mg/dL and 192 ± 271 pg/mL, respectively. MIBI, SUS, or both were performed in 503 (98%), 392 (76%), and 382 (74%), respectively, of 516 patients. There was no difference among patients who had MIBI alone (n = 121), SUS alone (n =10), or both scans performed. The proportion of patients having SUS in addition to MIBI scanning ranged from 5% to 94% each year during the study and remained essentially constant over the period 2004–2009.

Table 1.

Study Patients

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| No of patients | 516 |

| Age, y, mean (median, range) | 57.6 (58, 14–87) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 114 (22%) |

| Female | 402 (78%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 366 (71%) |

| Black | 134 (26%) |

| Other | 16 (3%) |

| Preoperative calcium level (mg/dL) | 10.9 ± 0.9 |

| Preoperative PTH (pg/mL) | 192 ± 271 |

| Underwent MIBI alone | 121 (23%) |

| Underwent SUS alone | 10 (2%) |

| Underwent Both MIBI and SUS | 382 (74%) |

| SUS and MIBI Concordant | 289/382 (76%) |

| SUS and MIBI Discordant | 93/382 (24.3%) |

PTH, parathyroid hormone; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound.

Imaging of the 516 sporadic PHPT patients revealed ≥1 candidate parathyroid/adenoma in 475 patients. This included 357 (91%) positive SUS and 394 (78.3%) positive MIBI scans (Table 2). For SUS, a TP scan was obtained in 342 (87%) of 357 patients, giving a sensitivity and positive predictive value of 91% and 96%, respectively. An FN SUS examination occurred in 32 patients (8%) and an FP in 15 cases (4%). For MIBI, a TP exam occurred in 383 (76%) of patients, for a sensitivity and positive predictive value of 78% and 97%, respectively. An FN MIBI occurred in 105 (21%) patients and an FP in 11 (2%) patients. There was a significant difference in the TPs, FNs, and sensitivities between SUS and MIBI in favor of SUS.

Table 2.

Results of SUS and MIBI Studies

| Variable | SUS | MIBI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 392 | 503 | — |

| Test result | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 357 (91%) | 394 (78.3%) | |

| Negative | 35 (9%) | 109 (21.7%) | |

| True Positive* | 342 (87%) | 383 (76%) | <0.001 |

| False Positives† | 15 (4%) | 11 (2%) | NS |

| False Negative‡ | 32 (8%) | 105 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity | 91% | 78% | <0.001 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 96% | 97% | NS |

| Multiple target scan (>1 abnormal gland identified) | 9 (2%) | 8 (2%) | NS |

For true and false positives, data are based on correct lateralization.

One patient with a false positive SUS had a negative exploration.

Three patients with negative SUS had negative explorations, and 4 patients with negative MIBI had negative explorations.

MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound.

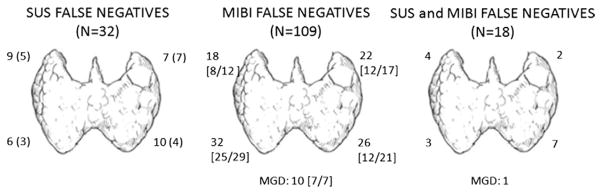

Among the 382 patients who had both imaging tests performed, 276 (72%) had both imaging tests positive (Fig 1). There were 72 (19%) SUS-positive/MIBI-negative cases and 16 (4%) MIBI-positive/SUS-negative cases. Multiple parathyroid tumor candidates were identified in 9 SUS exams and 4 MIBI, respectively. In 18 cases (5%), both SUS and MIBI scans were completely negative. Of the patients that had both studies performed, the scans were concordant positive in 276 cases, concordant negative in 18 cases, and discordant in 88 cases (Table 3). When both scans were concordant positive, a single parathyroid adenoma was identified in 257/276 patients (93%) and multiple gland disease found in 19/276 (7%). No patients with concordant positive scans had unsuccessful surgery. When discordance occurred, SUS was TP in 67/72 cases (93%) and MIBI was TP in 15/16 cases (94%). Concordant negative scans occurred in 18 patients. When both SUS and MIBI were negative, single-gland disease was present in 17/18 patients. The mean preoperative calcium, mean PTH, and median weight of the image-occult glands were 10.9 ± 0.6 mg/dL, 154 ± 53 pg/mL, and 490 mg, respectively. These values were not significantly different than patients with positive scans. The location of surgically identified parathyroid glands in image-negative cases is shown in Fig 2.

Table 3.

Concordant and Discordant Imaging Tests

| Discordant

|

Concordant

|

p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIBI−, SUS+ (n =72) | MIBI+, SUS− (n =16) | MIBI−, SUS− (n =18) | MIBI+, SUS+ (n =276) | ||

| MGD, n (%) | 7 (10%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 19 (7%) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Preop Ca, mg/dL | 11.0 ± 0.7 | 11.1 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.7 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Preop PTH, pg/mL | 146 ± 83 | 310 ± 546 | 154 ± 53 | 192 ± 235 | 0.016* |

|

| |||||

| Gland wt, mg, median (range) | 365 (120–10,100) | 1430 (270–2,410) | 490 (90–2,090) | 875 (65–9,200) | NS |

|

| |||||

| Failed exploration | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | NS |

|

| |||||

| Recurrent HPT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NS |

MIBI−, SUS+ vs MIBI+, SUS−.

MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MGD, multiple-gland disease; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Figure 2.

Location of image-negative parathyroid adenomas identified at surgery. Adenoma locations were generally assigned to a specific quadrant as shown. Numbers indicate gland location identified at surgery. Numbers in parentheses indicate patients with a false negative SUS and true positive MIBI. Numbers in brackets indicate patients with false negative MIBI and true positive SUS (denominators differ because not all patients undergoing MIBI had an SUS performed). SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; MGD, multiple-gland disease.

To determine the relative value of the addition of MIBI to SUS in an unbiased fashion, we examined results for each imaging modality when we could clearly document that SUS was performed before ordering and performing MIBI (Table 4). A total of 156 patients of the 382 patients who had both studies performed had SUS performed before MIBI. In these cases, a parathyroid candidate was identified in 140 (90%), with a TP SUS in 131 cases (84%). The frequency of TP SUS in SUS-first cases was 84%, compared with 88% in TP SUS-second or sequence-unknown cases, and although there is a 4% difference it was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In the 16 cases of FN SUS, MIBI provided useful information in 12 instances (75%). Among the 8 FP SUS, MIBI showed the correct location in 3 cases (43%).

Table 4.

Results of Unbiased Imaging Studies

| Variable | SUS first | MIBI first | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 156 | 214 | — |

| Test result* | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 140 (90%) | 163 (76%) | |

| Negative | 16 (10%) | 51 (24%) | |

| True positive | 131 (84%) | 158 (74%) | 0.013 |

| False positive† | 8 (5%) | 5 (2%) | NS |

| False negative‡ | 16 (10%) | 49 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity | 89% | 76% | <0.001 |

| Positive predictive value | 94% | 97% | NS |

| Additional localizing study | 0.003 | ||

| Helpful§ | 12 (8%) | 38 (18%) | |

| Unnecessary | 144 (92%) | 176 (82%) |

For true and false positives, data are based on correct lateralization.

One false positive SUS had a negative neck exploration.

One false negative SUS and 2 false negative MIBI patients had negative explorations.

“Helpful” was defined as a false negative or false positive result with subsequent true positive localizing study.

MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound.

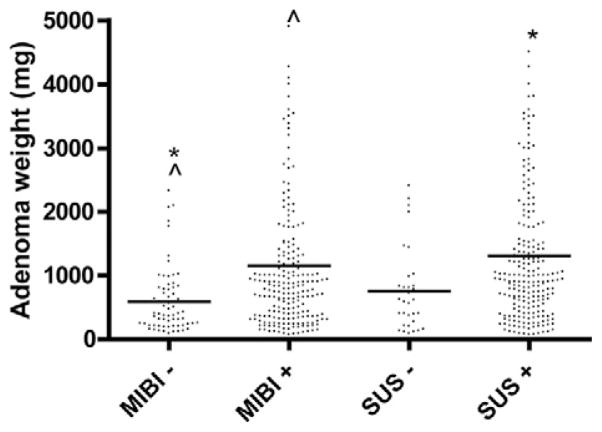

Surgical findings in relation to imaging results are documented in Table 5. Single-gland disease, as defined by PTH drop of 50% and into the normal range, was encountered in 92.1%, and multiple-gland disease was found in 7.9% of patients. The frequency of multiple gland disease in patients with negative SUS and MIBI was 6% (3/50) and 9.1% (11/120), respectively (p > 0.05). When both SUS and MIBI were negative, single-gland disease was found in 94% (17/18) and multiple-gland disease in 6% (1/18). When both SUS and MIBI were positive, multiple-gland disease occurred 7% (19/276). Adenoma weight was compared across negative and positive imaging studies (Fig. 3). This demonstrated that MIBI-negative glands were smaller than MIBI-positive and SUS-positive glands. However, there was no statistical difference in gland weight between SUS-negative glands and SUS-positive glands. Furthermore, univariate and multivariate analyses was performed across demographic and preoperative variables and demonstrated no significant associations with SUS FNs and FPs. At a median follow-up of 9 months, there were 4 cases of persistent and 6 cases of recurrent PHPT in our study group.

Table 5.

Surgical Results

| SUS TP (n =342) | SUS FN/FP (n =46) | MIBI TP (n =383) | MIBI FN/FP (n =116) | Total (n =516) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGD, n (%)* | 26 (7.6%) | 3 (7%) | 29 (7.6%) | 11 (9%) | 41 (7.9%) | NS |

| Pre-op Ca, mg/dL | 11.2 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 10.9 ± 0.7 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | NS |

| Pre-op PTH, pg/mL | 184 ± 215 | 154 ± 67 | 201 ± 262 | 148 ± 90 | 192 ± 271 | 0.005† 0.02‡ |

| Gland wt, mg, median (range) | 785 (80−10,100) | 615 (90−2,410) | 915 (65−9,200) | 400 (90−10,100) | 800 (65−10,100) | 0.006§ |

TP for MGD defined as any abnormal gland noted before neck exploration.

SUS TP vs SUS FN/FP.

MIBI TP vs MIBI FN/FP.

MIBI TP vs MIBI FN/FP.

TP, true positive; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MGD, multiple-gland disease; ′PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Figure 3.

Weights of image true positive and false negative parathyroid adenomas. SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan. *p value < 0.001; ^p value < 0.001.

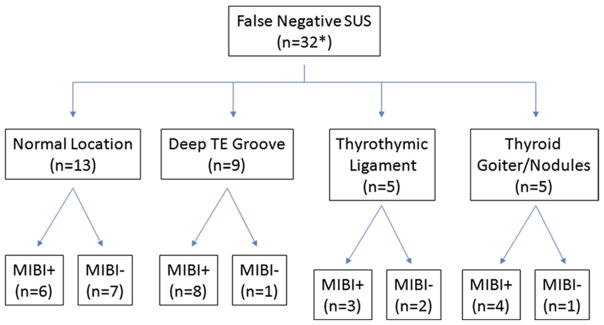

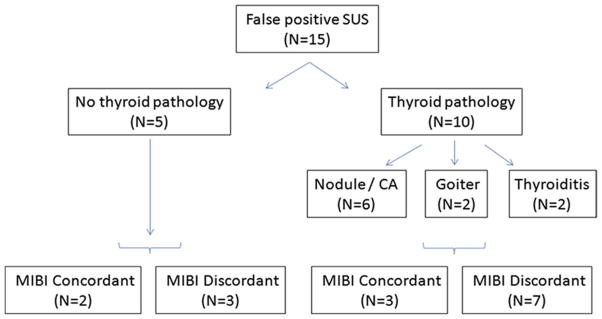

Analysis of inaccurate SUS localization studies was performed. There were a total of 32 FN SUS identified. The probable reasons behind FNs are shown in Fig 4. These include gland location in either the deep tracheoesophageal groove (n = 9) or the thyrothymic ligament below the clavicle (n = 5), concurrent thyroid goiter (n = 4), or thyroid cancer (n = 1). In 13 cases, the adenoma was located in a normal ultrasound-accessible location but was missed by the preoperative exam. In these 32 FN SUS cases, MIBI scans were positive in 21 (66%). There were 15 FP SUS exams (Fig 5). Among these patients, concurrent thyroid pathology was present in 10 (66%), including 6 patients with thyroid nodules and/or cancer and 4 patients with either goiter or thyroiditis. In 5 patients, there was no discernible explanation for the FP SUS.

Figure 4.

Anatomic location and MIBI positivity of patients with false negative SUS results. *Three patients with negative SUS had negative exploration not allowing definitive assignment of false negative status. SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan; TE, transesophageal groove.

Figure 5.

Concurrent thyroid pathology and MIBI results of patients with false positive SUS results. SUS, surgeon-performed ultrasound; MIBI, Tc-99m sestamibi scan.

DISCUSSION

Preoperative imaging of patients who are to undergo parathyroidectomy for PHPT has become routine practice.7 Options for noninvasive testing include MIBI, cervical ultrasound, and cross-sectional imaging with either CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Currently, MIBI is the most widely used imaging modality, and this approach works well for many patients, with a published sensitivity of 39% to > 90%.2 High-resolution cervical ultrasound is increasingly being used and has a published sensitivity of 47% to 94% and a positive predictive value of 98%.9,10

SUS for PHPT has been studied by several groups. Jabiev et al reviewed their experience with 442 patients and had 76.5% TPs. Those authors subsequently began to use SUS as their only localization test if clearly identifying an abnormal gland and reported operative successes.11 Siperstein et al found an accuracy rate of 75% of patients with single-gland disease,3 and another series of 226 patients had a 77% success rate for identifying abnormal glands.4 Steward et al reported one of the highest success rates for ultrasound: a sensitivity of 91% in 103 patients.12 The present results of unbiased imaging are similar to these earlier studies (84% TP, 89% sensitivity). The variability across series suggests that the training and experience of the ultrasound operator is important for identifying abnormal glands. Underscoring this point is the sensitivity of 57% found by Purcell et al, in which the ultrasound was performed not by the operating surgeon but instead in radiology.13

Another question raised in earlier studies was whether there was an advantage of SUS over MIBI. In most series, the preoperative imaging success is suggested to be better with SUS than with MIBI.3,12 However, our data clearly demonstrate that SUS is a more accurate than MIBI, an effect that persisted when SUS was performed before obtaining a MIBI result. Our data support the conclusions of earlier authors and extend the literature on the subject by showing that when SUS is performed as the first imaging study and is positive, MIBI adds little additional information to guide surgery.4

Patients with discordant parathyroid imaging pose a dilemma for the surgeon. In our experience of 88 discordant cases, we have found that both SUS and MIBI can be useful for localization. Nevertheless, for targets identified by both studies, we routinely examine both regions to exclude multiple-gland disease. Of the 18 patients with concordant negative imaging, the location of the abnormal gland was distributed uniformly in typical locations (p > 0.05). Finally, the frequency of multiple-gland disease in this circumstance was equal to MIBI- or SUS-positive patients. Therefore, for these patients a high index of suspicion for multiple-gland disease must be maintained, as well.

Limitations of the present study that must be kept in mind when interpreting the data include the retrospective nature of the analysis and the exclusion of patients who were expected to have multiple-gland disease (ie, familial, secondary, and tertiary HPT). In addition, the performance of MIBI at our center falls below some published experience, making SUS seem the better test by comparison.14 Finally, these results were obtained by high-volume endocrine surgeons with a dedicated interest in endocrine imaging. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable across the spectrum of surgeons who perform parathyroidectomy.

Despite the limitations of the present study, this analysis of our experience supports the findings of others in this regard and has provided the rationale for our policy of including SUS in the routine preoperative evaluation of patients having parathyroidectomy for PHPT and for our ongoing move away from routine MIBI for patients who have a positive SUS. For patients facing first-time surgery for PHPT, we now reserve MIBI for patients with unclear or negative SUS. This policy has not affected our ability to perform minimally invasive parathyroidectomy through small incisions and still allows use of a radioguided approach for appropriate patients. In fact, the multidimensional, real-time localization afforded by SUS has made minimally invasive parathyroidectomy more feasible in our experience. For these reasons, we think that SUS is the best first imaging study for patients having parathyroidectomy for sporadic PHPT. In most cases, this is the only localization test required and extends the philosophy of John Doppman: “The most difficult challenge in preoperative localization in primary hyperparathyroidism is locating the parathyroid surgeon”—who performs ultrasound.15

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- MIBI

Tc-99m sestamibi scan

- PHPT

primary hyperparathyroidism

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- SUS

surgeon-performed ultrasound

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Presented at Southern Surgical Association 122nd Annual Meeting, Palm Beach, FL, December 2010.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Olson, Untch, Adam

Acquisition of data: Dixit, Webb, Adam, Untch

Analysis and interpretation of data: Olson, Leight, Scheri, Untch, Bennett, Adam

Drafting of manuscript: Olson, Untch

Critical revision: Olson, Untch

References

- 1.Coakley AJ, Kettle AG, Wells CP, et al. 99Tcm sestamibi—a new agent for parathyroid imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 1989;10:791–794. doi: 10.1097/00006231-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotthardt M, Lohmann B, Behr TM, et al. Clinical value of parathyroid scintigraphy with technetium-99m methoxyisobutylisonitrile: discrepancies in clinical data and a systematic meta-analysis of the literature. World J Surg. 2004;28:100–107. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6991-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siperstein A, Berber E, Mackey R, et al. Prospective evaluation of sestamibi scan, ultrasonography, and rapid PTH to predict the success of limited exploration for sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2004;136:872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solorzano CC, Carneiro-Pla DM, Irvin GL., 3rd Surgeon-performed ultrasonography as the initial and only localizing study in sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller BS, Gauger PG, Broome JT, et al. An international perspective on ultrasound training and use for thyroid and parathyroid disease. World J Surg. 2010;34:1157–1163. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis ML, Quayle FJ, Middleton WD, et al. Ultrasound facilitates minimally invasive parathyroidectomy in patients lacking definitive localization from preoperative sestamibi scan. Am J Surg. 2007;194:785–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consensus development conference statement. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:S9–S13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650061406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Untch BR, Barfield ME, Dar M, et al. Impact of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency on perioperative parathyroid hormone kinetics and results in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2007;142:1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilat H, Cohen M, Feinmesser R, et al. Minimally invasive procedure for resection of a parathyroid adenoma: the role of preoperative high-resolution ultrasonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:283–287. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihai R, Simon D, Hellman P. Imaging for primary hyperparathyroidism—an evidence-based analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:765–784. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabiev AA, Lew JI, Solorzano CC. Surgeon-performed ultrasound: a single institution experience in parathyroid localization. Surgery. 2009;146:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steward DL, Danielson GP, Afman CE, et al. Parathyroid adenoma localization: surgeon-performed ultrasound versus sestamibi. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1380–1384. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000227957.06529.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell GP, Dirbas FM, Jeffrey RB, et al. Parathyroid localization with high-resolution ultrasound and technetium Tc 99m sestamibi. Arch Surg. 1999;13:824–828. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.8.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denham DW, Norman J. Cost-effectiveness of preoperative sestamibi scan for primary hyperparathyroidism is dependent solely upon the surgeon’s choice of operative procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:293–305. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diagnosis and management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism. NIH Consens Statement. 1990;8:1–18. [Google Scholar]