Abstract

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are recognized as playing an exceptional role in the global AIDS response. However, there is little detailed research to date on how they contribute to specific governance functions. This article uses Haas’ framework on global governance functions to map CSO’s participation in the monitoring of global commitments to the AIDS response by institutions and states. Drawing on key informant interviews and primary documents, it focuses specifically on CSO participation in Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting and in Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria processes. It argues that the AIDS response is unique within global health governance, in that CSOs fulfill both formal and informal monitoring functions, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of these contributions. It concludes that future global health governance arrangements should include provisions and resources for monitoring by CSOs because their participation creates more inclusive global health governance and contributes to strengthening commitments to human rights.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, monitoring, civil society organizations, UNAIDS, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

INTRODUCTION

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are generally recognized as playing an exceptional role in the global AIDS response [1]. They mobilize communities to demand services, act as service providers, and gather strategic information that informs policies. The importance of civil society participation led by people living with HIV/AIDS is enshrined in the Greater Involvement of People with AIDS principle, originally agreed to at the Paris AIDS Summit in 1994, and adhered to by the majority of AIDS focused CSOs and global health institutions (GHI) since. As a result, CSO are credited with making global health governance (GHG) processes more transparent and accountable. However, Doyle and Patel point to a gap in understanding the outcomes of CSO participation [2]. In order to learn lessons for strengthening GHG through CSO participation, there is need for detailed analysis and assessment of their participation in specific governance functions.

This article draws upon Haas’ framework of global governance formal and informal functions to map CSO’s participation in the monitoring of global commitments to the AIDS response by institutions and states [3]. CSOs are among the many non-state actors that have contributed to what Haas describes as a “proliferation of new political actors and the diffusion of political authority over major governance functions”[3]. Haas maps the division of labour among actors in global governance according to twelve functions; here we focus specifically on the monitoring function. Haas notes that monitoring can be performed formally, “by the direct commitment by somebody to be a clear actor to perform the designated function or functions,” or informally by which “the functions may be observed but are not the consequence of intended action by those contracting some set of activities to be performed by the relevant actors.” Lee, extending Haas’ framework to GHG instruments, argues CSO largely fill informal monitoring roles [4]. Here we assess the monitoring functions of CSOs in the global AIDS response to determine strengths and weaknesses of informal and formal approaches.

While a comprehensive analysis of CSO monitoring in regional, national and local contexts lies beyond the scope of this article, an examination of CSO participation within United Nations Joint Program on AIDS (UNAIDS) led Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting (GARPR), and selected Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) processes offers potential lessons for strengthening GHG. These processes were selected as key examples of monitoring processes within the global AIDS response as the GARPR includes the majority of United Nations member states, and GFATM is the largest multilateral funding body in the AIDS response.

METHODS

To understand how CSOs participate in monitoring functions, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants consisting of current and former staff of UNAIDS (4) and GFATM (3), and with CSO representatives (8). The initial interviewees were purposefully selected with snowball sampling used to generate follow up interviews. Interviews conducted by author JS (all except two UNAIDS staff and two CSO interviews) were part of a broader study, from 2013 – 2015, on the role of CSOs in the global AIDS response. Ethical approval for the interviews was obtained from the University of Bradford, where JS was based at the time. The remaining interviews were conducted by CM in 2015, with approval from UNAIDS, in order to fill identified gaps in the research. CSO interviewees were from organizations that had knowledge of the monitoring processes considered here, and so represented national and regional CSOs that engage with GHIs. CSO representatives were drawn from varying regions including those based in Europe (2), Sub-Saharan Africa (2), Latin America (2), North America (1) and Asia (1). Five of the interviewees identified as people living with HIV/AIDS. Eight women and nine men were interviewed. Interview questions were semi-structured and focused on respondents’ experiences of monitoring processes, and perceptions of civil society participation and influence within them.

Interviews were initially analyzed by JS using inductive thematic analysis. Themes were derived conceptually, based on the concepts emerging from secondary literature and analysis of primary documents. Substantive codes were further derived throughout the research process, and discussed with co-authors at regular intervals. Contradictions and conflicting information was discussed and situated within the broader context, and in relationship to other data.

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of data in reports from CSOs, states and institutions was also carried out to identify involvement in monitoring. These documents included reports on the GFATM Partnership Forum, global AIDS reports from UNAIDS, shadow reports, documents from the UNAIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Reference Group (MERG), and country submissions through the National Commitments and Policy Instrument (NCPI) [6]. Documents were analyzed using the same thematic analysis used for the interview transcripts, and where compared and contrasted with each other. Data was then triangulated with semi-structured interviews and secondary literature on CSOs and GHG functions.

We are aware that both author and interviewee bias may influence the interpretation of results that follows. In particular, the participation of some of the co-authors in monitoring processes described, and connections to interviewees through UNAIDS, implies the likelihood of a subjective analysis. We tried to mitigate this by having authors external to the processes described take a lead role in the analysis, and through discussion among all co-authors regarding the interpretation of data. That said, we do recognize the possible subjectivity in the analysis that follows and encourage other researchers to consider the topic from additional stand points.

RESULTS

Using Haas’ concept of informal and formal monitoring roles, Table 1 lists examples of CSO monitoring functions related to GARPR and the GFATM.

Table 1.

CSO participation in monitoring functions related to GARPR and GFATM

| Formal | Informal | |

|---|---|---|

| GARPR |

|

|

| GFATM |

|

|

Formal Participation in GARPR

The 2001 and 2011 UN General Assembly declarations related to AIDS recognized CSOs as key actors in the global AIDS response. The 2001 declaration specifically mentioned the importance of including CSOs in monitoring, encouraging states to “Conduct national periodic reviews with the participation of civil society, particularly people living with HIV/AIDS” [5]. CSOs, through advocacy campaigns and as observers at UN meetings, played a key role in shaping the content of UN declarations on AIDS, which include commitments by Member States and global targets on prevention, treatment, care and support, and human rights of affected populations. For example, CSOs successfully advocated for Article 29 of the 2011 UN General Assembly Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS to specifically refer, for the first time, to the need to address the rights of key populations [6].

Indicators of the GARPR, which monitor member state progress towards the commitments of the declarations, are developed by UNAIDS’ MERG, a group of independent experts including CSO representatives. CSO participants on the MERG have been able to ensure the most recent version of the GARPR guidelines include an indicator to reduce intimate partner violence, and another on the elimination of stigma and discrimination [6]. However, CSO influence on the MERG is limited by the need to achieve consensus with the other representatives who resist efforts to develop rights-based indicators [7].

Global AIDS reporting guidelines include strong language on the importance of including civil society in country level reporting, and state that UNAIDS country offices should provide support to CSOs through briefings on the indicators and the reporting process, provide technical assistance on gathering, analyzing and reporting data, provide focused support to people living with HIV, and ensure the dissemination of reports including, whenever possible, in national languages [8]. The key monitoring tool at the country level is the NCPI, which provides a framework for results to be compared across countries and over time. The NCPI report is divided into two parts: the first is completed by governments and the second by other actors. In most countries “other actors” include bilateral and multilateral organizations, CSOs and private sector actors. The two report sections are distinct, but contain significant overlap, allowing comparison of governmental and other responses. CSOs are particularly asked to document “civil society involvement” including engagement in M&E, and the reporting process.

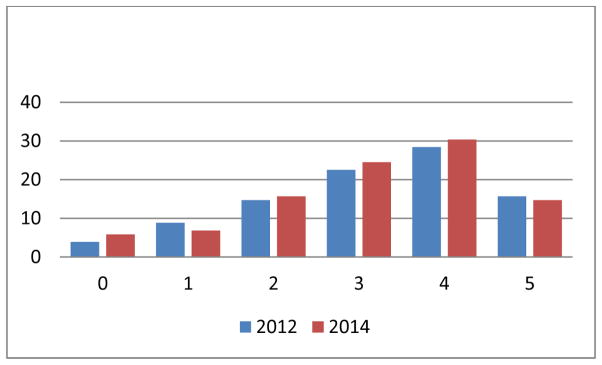

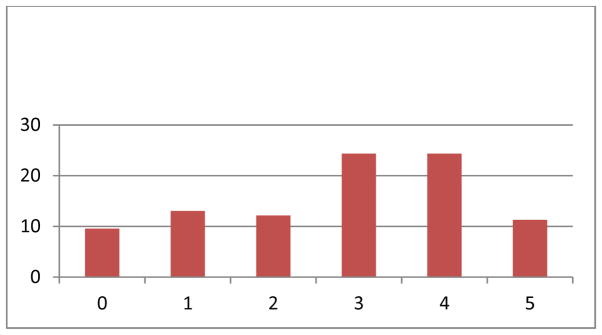

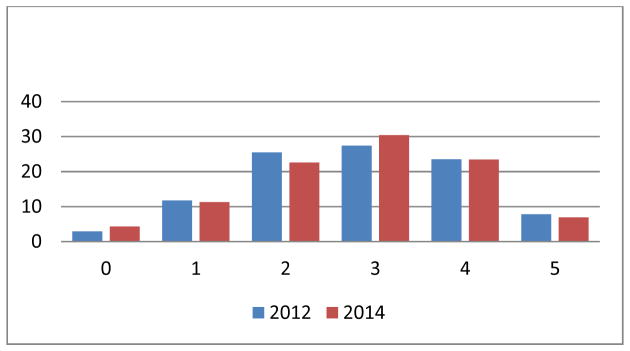

In 2012 and 2014, 102 countries submitted the CSO section of the NCPI in both reporting rounds1, including analysis of the extent to which civil society was included in the M&E of the HIV/AIDS response. The questions used a scale where 0 is “low” and 5 is “high” level of participation. The data on countries where CSOs took part in filling in the NCPI showed that they rank their participation as medium to high for the development of the national M&E plan (Figure 1), participation in M&E working groups (Figure 2), and participation in the use of data (Figure 3) [9], [10]. For the two questions with data from both years (Figures 1 and 3) no major difference is apparent between 2012 and 2014. The majority of participants in 2014 ranked CSO participation in national M&E activities as mid to high (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Extent CSOs included in development of national M&E plan.

0 is “low” and 5 is “high” level of participation; X axis indicates number of country reports submitted

Figure 2. CSO participation in national M&E committee/working group responsible for coordination of M&E activities (2014).

0 is “low” and 5 is “high” level of participation; X axis indicates number of country reports submitted

Figure 3. CSO participation in using data for decision-making.

0 is “low” and 5 is “high” level of participation; X axis indicates number of country reports submitted

Perspectives from interviewed UNAIDS staff indicate that the NCPI provides an opportunity, not only for CSOs to engage in monitoring, but also in dialogue with governments. As one UNAIDS staff member based in Latin America notes, “the NCPI has represented an opportunity for CSOs to provide inputs into data collection efforts and has allowed them to bring up problematic issues within the national responses”[11]. Similarly, one CSO representative stated, in regards to reporting on stigma and discrimination, “when the answers given by civil society vary from those given by the government, then it is clear that the government is either sugar coating the situation to look better among UN Member States or really does not understand how their laws are discriminatory. Either reason means that civil society now has an opportunity to use the GARPR process to press their government to do better” [12].

Some CSO members identify limitations in the current process. One representative from a national network noted that her organization had never been invited to participate in the NCPI [13]. A CSO representative from a regional organization noted that, although she was aware of the NCPI, “I haven’t heard how any country or CSOs have actually operationalized the NCPI process”[14]. While, not all CSOs can, or would want to, engage in the NCPI, which CSOs are invited to participate raises questions about access and inclusivity within the state led reporting processes.

Informal Monitoring through Shadow Reports

In countries where CSOs feel that civil society is not adequately included in the national reporting process, where governments do not submit a report, or where data provided by government differs considerably from data collected by CSOs, an alternative process has developed called “shadow reporting” [15]. Shadow reports are not intended to be parallel reporting processes, but rather provide sources of triangulation to compare reports on progress towards achieving AIDS-related commitments. This is particularly important for monitoring policies, services and programmes that affect key population groups for whom government data is not disaggregated, or where participation in formal monitoring processes is not possible. Shadow reports are numerous and impossible to list here. They range from series such as the Missing the Target reports from the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition (ITPC) which monitor treatment delivery [16], to analysis of legal and policy environments such as the Global Criminalisation Scan led by Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) [17].

It is notable that, in 2006 the Global AIDS Progress Report included more than 30 shadow reports [18], but only seven were produced in 2012 [19], and none were submitted in 2014 [20]. In some countries, this decrease is seen as a sign that CSOs are increasingly included in formal decision-making or in agreement with government reported results. In other contexts, this decrease is viewed as a sign of shrinking political space for CSOs to participate in accountability processes or lack of funding for monitoring. More research is needed to determine why shadow reporting has declined as it presents a way for CSOs to monitor progress on commitments within their own terms.

Formal Monitoring through GFATM Partnership Forum

At the global level, CSOs formally participate in multiple GFATM committees including the Partnership Forum. The Forum aims to allow stakeholders “to express their views on the GFATM’s policies and strategies,” with a core function being to “review progress based on reports from the Board and provide advice to the GFATM on general policies”[21]. Partnership Forums have been held in Thailand in 2004, in South Africa in 2006, in Senegal in 2008, and in Brazil in 2011, with an online forum held in 2015. Previous forums included online and regional consultations, as well as global meetings of 200 to 500 participants from CSOs, donors and the private sector. Twenty-nine percent of participants at the 2011 forum were from CSOs, representing the largest stakeholder group [22].

A key function of the Forum is to make recommendations that go to the Strategy Investment and Impact Committee, in order to be presented to the Board. Thus, it provides a direct process for CSOs to monitor GFATM planning and actions. As one CSO participant describes, “I think that it was an amazing meeting...it really went to the heart of the issues of the Fund. And at the time you know that the recommendations are going somewhere” [7]. At the Forum, CSOs also reflect on developments and future frameworks. For example, at the 2011 Forum, the Human Rights Break Out Group influenced the 2011–16 strategy document commitments to human rights. While the draft prior to the Forum committed the GFATM to, “Stimulate greater programmatic attention and investment to overcome stigma and discrimination,” the draft after the forum committed the Fund to, “Increase investments in programs that address human rights-related barriers to access” [23]. Similarly, wording was strengthened from, “Take steps to ensure the Global Fund is not supporting programs that violate human rights” to “Ensure that the Global Fund does not support programs that infringe human rights” [20]. This stronger commitment to human rights was attributed to CSO input [24].

However, the Partnership Forum faces limitations in terms of accessibility and enforcement. At the 2011 forum, participants complained of confusion and lack of transparency over who was able to participate [18]. Furthermore, while CSOs could make recommendations to the Board, they had no recourse to follow-up on how/if these were acted upon. Further research is needed to determine if the 2015 online forum addressed these limitations.

Informal Monitoring by CSOs as External Watchdogs

While CSOs engage with GFATM through various formal and informal relationships, the size and scope of the GFATM creates monitoring challenges. One major issue is the amount of information the Fund produces. Prior to one Board meeting 900 pages of documentation was distributed for delegates to condense, share and solicit feedback [25]. Furthermore, because GFATM is a dynamic organization, it changes policies frequently, creating a constant game of catch-up for stakeholders [26]. Research in Latin America found that many women’s groups felt unable to engage with GFATM processes because of the technical expertise needed to understand rapidly changing policies [27].

Recognizing these challenges, CSOs such as the HIV/AIDS Alliance, Open Society Institute, and Aids Accountability have taken on the role of synthesizing and distributing GFATM information. In Latin America, a group of CSOs established El Observatorio Latino which reports on GFATM disbursements in the region [7]. These CSOs condense data and reduce the complexity of information for target audiences. One monitoring-focused CSO is Aidspan, which publishes a Guide to the GFATM and the Global Fund Observer (GF0). The GFO, a monthly e-newsletter, is distributed to over 10,000 subscribers in over 170 countries, and on the Aidspan website, providing factual articles and commentaries. A CSO representative notes that the factual reports serve a watchdog function: “To some extent, just by reporting the facts we are facilitating the accountability process, even if it is not us wagging our fingers. Other people can wag their fingers based on what we are reporting” [28].

CSOs demands for open information can lead to conflicts with states and institutions. As one GFATM representative observed, “I had to tell them, Aidspan is an external observer that is supposed to report on facts...Everybody feels they have the right to have all this information” [26]. Such tensions can be pronounced at the country level where CSOs fear conflicts might impact funding. In one case, a CSO was threatened with deregistration when it asked the government questions about GFATM resources [24]. These conflicts also reflect CSO struggles to use the information they gather to influence change. Lee notes the limits on CSO influence when they do not have formal authority [4]. However, conflicts between CSOs and other actors during monitoring processes can also have positive long-term outcomes. The GFTAM staff member quoted above also noted that GFO reporting compelled the GFTAM to make its information more accessible, and the CSO that was threatened with deregulation was eventually able to work with the government to improve transparency [24].

DISCUSSION

Previous analysis has found that CSOs serve largely informal monitoring roles within GHG [4]. However, this paper finds that, in the global AIDS response, CSOs have fulfilled both formal and informal monitoring functions. CSOs have been exceptional in their contribution within the realm of AIDS, acting as participants in formal processes, accepted as key stakeholders and provided with opportunities to influence decision making including commitments to action and the indicators measuring progress towards them. The GHG of AIDS, in this sense, offers potential lessons for expanding the role of CSOs in other global health issue areas, as is evident in the way Malaria and TB CSOs have engaged with GFATM based on the precedent set by AIDS CSOs.

CSOs have particularly played an important role in strengthening commitments to human rights. Whether this is by ensuring related targets are included, such as by influencing UN declarations and GFATM strategies, or by representing key populations in GARPR processes, CSO participation continues to challenge institutions and states to make and monitor human rights commitments.

At the same time, there remain challenges to CSOs as they seek to fulfill an effective formal monitoring function. Formal status allows for more direct influence in policy making, enhanced ability to communicate information to other CSOs, and better opportunities to dialogue with government and other stakeholders. Yet formal roles can also be restricted in format and timeframe; can limit the number and type of CSOs granted permission to participate, and CSOs may still lack the authority to enforce decisions. As described above, for example, the GARPR encourages government and CSOs to come together, in principle, to consensually discuss the national response to AIDS. By encouraging dialogue between governments and civil society, GARPR facilitates public scrutiny of government policy and strengthens national accountability [29]. However, how many and which specific CSOs are permitted to formally participate is still decided by states and intergovernmental organizations. This, in turn, may constrain what CSOs are willing and able to report when undertaking monitoring activities.

Informal participation in monitoring processes has several strengths. A greater diversity of stakeholders can be potentially involved as they are not bound by constitutional restrictions or formal terms of reference. These CSOs are also less constrained in what they say or do, and can target their communications to particular audiences more freely. While outside of formal policy making bodies, they can sometimes wield influence indirectly. The weaknesses arising from informal roles include increased possibility of conflict with the institution or member states given the outsider status of CSOs. Indirect influence may also have limited sway over decision making. Finally, there is limited funding for CSOs to undertake monitoring. This includes resources for coordination, which can be necessary given the diversity and number of CSOs.

Findings presented here are limited by available data and the scope of this paper; there is need for more in-depth analysis. For example, while it is clear the number of shadow reports has declined over the years, we are still unable to explain this change. Furthermore, analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of informal and formal monitoring processes is limited to the perspectives of those interviewed and maybe influenced by the experiences of the authors. As there is room for further research on a number of issues raised here, including drawing on the extensive data available through the GARPR and the recent changes in GFATM processes, we hope other researchers might use the framework presented to continue the analysis, and propose additional or varying findings.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that, given their strengths and weaknesses, formal and informal participation in monitoring by CSOs can be viewed as complementary. Formal participation opens doors to key stakeholders, information and processes within global health initiatives. However, the price might be restrictions on what CSOs say, do and are allowed to know in order to maintain that formal status. Informal participation gives more freedom to CSOs, which is needed when critical reporting on commitments and activities is warranted. At the same time, this can be accompanied by limitations in access to information and the capacity to influence key players directly.

A core question in contemporary debates about the strengthening of GHG, namely the institutional arrangements that facilitate collective action on shared health needs, is what appropriate role should non-state actors play. A useful approach to begin answering this question is to better understand the different functions which GHG entails, and to identify how different types of actors might contribute to them. Here we used Haas’ framework to situate CSO monitoring of commitments within these functions. We contend that, rather than seeing state and non-state actors as somehow inhabiting separate realms, and at times even being diametrically opposed, they could be seen as offering contributions to specific GHG functions. The experience described in this paper, based on the global response to AIDS, suggests that CSOs can contribute substantially to the important function of monitoring global commitments through both formal and informal roles. In this sense, fuller understanding of CSOs and their varied contributions is a key challenge in the future strengthening of GHG.

Table 2.

Potential Strengths and Weakness of CSO Monitoring Roles

| Formal | Informal | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths |

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

Footnotes

In total 173 submitted the NCPI in 2012 and in 2014 117 countries submitted the complete NCPI (including the CSO section), and 43 countries in Europe and Central Asia submitted responses to a shorter version, the so called Dublin Declaration questionnaire, not including all these questions.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Buse K, Blackshaw R, Ndayisaba M. Zeroing in on AIDS and global health Post-2015. Globalization and Health. 2012;8(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle C, Patel P. Civil society organisations and global health initiatives: Problems of legitimacy. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(9):1928–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas P. Is there a Global Governance Deficit and What Should be Done About It? Geneva: Ecologic; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K. Civil Society Organizations and the Functions of Global Health Governance: What Role within Intergovernmental Organizations? Global Health Governance. 2010;3(2):1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations. Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS; 25–27 June 2001; New York: United Nations; [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS Representative 1. Interviewed by Smith, J. 2013.

- 7.CSO Representative 4. Interviewed by Smith, J. 2013.

- 8.UNAIDS. Guidelines on Construction of Core Indicators. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2013. United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS: Monitoring the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCPI country reports submitted to UNAIDS 2012

- 10.NCPI country reports submitted to UNAIDS 2014

- 11.UNAIDS Representative 2. Interviewed by Mallouris, C. 2015.

- 12.CSO Representative 1. Interviewed by Mallouris, C. 2015.

- 13.CSO Representative 2. Interviewed by Mallouris, C. 2015.

- 14.CSO Representative 3. Interviewed by Mallouris, C. 2015.

- 15.UNAIDS. Global Aids Response Progress Reporting 2015, Construction of Core Indicators for monitoring the 2011 United Nations Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ITPC. [Accessed 15 May 2015];Missing the Target Reports. 2012 http://itpcglobal.org/?page_id=831.

- 17.GNP+ [Accessed 15 May 2015];Global Criminalisation Scan. 2015 http://criminalisation.gnpplus.net/

- 18.ICASO. [Accessed 15 May 2016];AIDS Advocacy Alert: Reviewing National AIDS Responses – How to Get Involved. 2007 http://www.icaso.org/publications/aa_aug07_FINAL.pdf.

- 19.UNAIDS. Shadow reports received. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNAIDS. Shadow reports received. Geneve: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed 30 April 2015];GFATM, Partnership Forum. 2015 http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/partnershipforum/

- 22.Centre Fremont. Global Fund Partnership Forum 2011: An Independent Evaluation. New York: Fremont Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.GFATM. A Strategy Framework For The Global Fund 2012 – 2016: Draft Revisions 1.1 and 1.2. Geneva; 2011. (emphasis added)

- 24.GFATM Representative 1. Interviewed by Smith, J. 2013.

- 25.MACRO. The Five-Year Evaluation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Synthesis of Study Areas 1, 2 and 3. Geneva: GFATM; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.GFATM Representative 2. Interviewed by Smith, J. 2013.

- 27.Global ICW. Governance Manual. Buenos Aires: International Community of Women Living With HIV/AIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.CSO Representative 5. Interviewed by Smith, J. 2013.

- 29.Taylor A, Alfven T, Hougendobler D, Tanaka S, Buse K. Leveraging Nonbinding Instruments for Global Health Governance: Reflections from the Global AIDS Reporting Mechanism for WHO Reform. Public Health. 2014;128(2):151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]