Abstract

In this two-wave longitudinal, daily diary study that followed up with 421 Mexican-American parent-adolescent dyads (adolescents: Mage = 15 years, 50% males) after one year, we investigated the contingency between parental stressors and adolescents’ emotional support to family members. Adolescents provided support to their parents and other family members at similar rates, but adolescents were more likely to provide support to other family members than to their parents on days when parents experienced a family stressor. This pattern was especially pronounced in families with parents who reported physical symptoms and adolescents with a strong sense of family obligation. Adolescents’ provision of emotional support was associated with same-day feelings of role fulfillment, but not to their concurrent or long-term psychological distress.

Adolescents’ provision of family caregiving has warranted great attention from professionals who work with children and families given concerns regarding the impact of family responsibilities on youth’s psychosocial adjustment. Research on parentification has documented the ways in which children assume caregiving responsibilities at home, which may include fulfilling their parent’s role to care for the parent or other family members (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Jurkovic, 1997). Although some studies have found adolescents’ caregiving behaviors to be detrimental to youth well-being (Gore, Aseltine, & Colten, 1993; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Williams & Francis, 2010), other findings indicate that adolescents’ provision of support is linked to important coping and social skills (Kuperminc, Jurkovic, & Casey, 2009; Stein, Rotheram-Borus, & Lester, 2007; Tompkins, 2006). With the increasing research on the breadth of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors, it is now understood that adolescents’ family responsibilities include diverse activities (e.g., household chores, providing advice) and can occur within a variety of family contexts. Therefore, it is important to contextualize adolescents’ caregiving behaviors in order to understand the implications of these activities for their well-being. In the current two-wave longitudinal, daily diary study that followed up with Mexican-American parent-adolescent dyads after one year, we investigated both the daily and chronic conditions under which adolescents provided emotional support to their families and how these behaviors are linked to their concurrent and long-term well-being.

We took a family systems approach to explore the nature of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors in several key ways. The family systems framework (Whitchurch & Constatine, 1993) purports that children’s behaviors are embedded within family dynamics involving other members. Therefore, the current daily diary study with adolescents and their parents allowed us to examine how adolescents’ caregiving behaviors may be contingent upon the needs and experiences of another family member. Moving beyond previous studies on parentification that have primarily centered on adolescents’ instrumental support or combined instrumental and emotional caregiving together as a single construct, we focused specifically on adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their families. Whereas instrumental caregiving involves meeting the practical and physical needs of the family and may be an aspect of youths’ everyday routines, emotional caregiving involves youths’ awareness and response to a stressor (Hooper, Marotta, & Lanthier, 2007; Kuperminc et al., 2009; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Peris, Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Emery, 2008; Titzmann, 2012; Williams & Francis, 2010). This type of emotional investment can have important implications for one’s well-being and interpersonal relationships that may not be evident in their provision of instrumental support. Furthermore, studies have operationalized caregiving behaviors to constitute support to both parents and other family members, and it remains unclear to whom adolescents provide immediate support. Making a clear distinction in regards to whom adolescents provide support can advance our understanding about how adolescents respond to their families during stressful circumstances. Lastly, our sample of Mexican-American families provides an ideal context to understand adolescents’ emotional caregiving. Families from Latino backgrounds endorse strong cultural values related to familism which emphasize family cohesion and support for one another (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003). Indeed, youth from Latino families display the highest rates of family assistance compared to their peers from Asian and European backgrounds (Tezler & Fuligni, 2013).

In the current study, we employed the daily diary methodology in order to examine the daily and chronic conditions that promote adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their families. Given that participants reported about events, behaviors and feelings on the same day as they occurred, the daily diary method provides more reliable and valid estimates, compared to retrospective accounts from one-time questionnaires (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Adolescents and parents both completed daily diary checklists during the same two-week period. Parents reported on the types of family stressors they experienced each day and adolescents reported on whether they provided emotional support to their parents and to other family members on the same days. This cross-informant approach enabled us to assess same-day associations between parents’ report of a family stressor and adolescents’ report of their provision of emotional support.

The Daily and Family Context of Adolescents’ Emotional Caregiving

Prior research on adolescents’ caregiving to their families demonstrates that children undertake household tasks in response to their family’s needs (Crouter, Head, Bumpus, & McHale, 2001; Gager, Sanchez, & Demaris, 2009; Tsai, Telzer, Gonzales, & Fuligni, 2013). Parents’ everyday strains can limit the time and energy they have to expend on their own caregiving responsibilities at home, and thereby increase their reliance on their children to help around the home. In this study, we examined whether parents’ daily family stressors at home (e.g., conflicts, family demands) would enlist adolescents to provide emotional support to their parent or other family members on that same day. On days when parents encounter a family stressor, adolescents may offer comfort directly to their parents. It is also possible that adolescents will extend their support to other family members in efforts to ease any tension that arose and restore family well-being and functioning. Adolescents may perceive the episodic stressor as one that not only affects their parent, but also the welfare of entire family, and thereby, lend their support to other family members as well.

In addition to examining the daily contingency between parents’ episodic family stressor and adolescents’ emotional caregiving, we explored whether chronic, pre-existing hardships (i.e., economic strain, parents’ physical health symptoms) would further promote adolescents’ emotional caregiving. Research on parentification has shown that adolescents living under severe economic hardships (Burton, 2007; McMahon & Luthar, 2007) or with a parent who has a medical illness (Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Stein et al., 2007; Tompkins, 2006) often assume responsibilities at home to care for their parent and family members. These types of financial and health adversities are stressors that often incapacitate parents’ ability to fulfill their own caregiving responsibilities and therefore, increase the need for their children to meet both the practical and emotional needs of their family. In the current study, we examined whether parents’ financial hardships and physical health symptoms would further promote adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their families on days when their parents are also confronted with a family stressor. Having to deal with conflicts or meet unforeseen demands, in and of itself, is stressful and can interfere with parents’ ability to fulfill their own caregiving responsibilities. For parents who also face chronic economic hardships or physical health ailments, the combination of both episodic and chronic stressors, may place parents and the family at an even greater need of emotional support. We expected that particularly stressful days (i.e., days when parents experience a family stressor) will prompt adolescents to provide emotional support to their families, and this response will be heightened within the context of concurrent family hardships (i.e., economic strain, physical health symptoms).

Variation in Emotional Caregiving Due to Adolescents’ Individual Characteristics

To further explore the nature of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors, we also sought to examine whether adolescents’ provision of emotional support would vary as a function of adolescent characteristics.

Cultural factors: Family obligation values and generational status

The current study with Mexican-American families provides a unique opportunity to explore whether the provision of emotional support may be a culturally relevant and meaningful practice. Latino families are often characterized by their strong sense of familism as evidence by their endorsement of family obligation values – the psychological sense that one should support, respect and spend time with the family (Fuligni et al., 1999; Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003). Indeed, family obligation values are manifested in adolescents’ daily provision of instrumental support at home (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009; Tsai et al., 2013) and we believe that the provision of emotional support is similarly embedded in youths’ internalization of family obligation values.

Furthermore, the challenges associated with adapting to and raising a family in a new country can be difficult for immigrant parents and necessitate greater support from their children. For instance, children from immigrant families often serve as language brokers for their parents by translating materials or facilitating conversations from English to their parents’ native language (Dorner, Orellana, & Jiménez, 2008). In general, adolescents from immigrant backgrounds provide greater instrumental support to their families, compared to their non-immigrant peers (Fuligni et al., 1999; Titzmann, 2012). We expected that adolescents with strong family obligation values and those from immigrant backgrounds (i.e., either adolescent or parent was born in Mexico) would demonstrate higher levels of emotional caregiving in response to parental need, compared to their peers with weaker family obligation values and those from non-immigrant families (i.e., both adolescent and parent were born in the U.S.).

Gender and birth order

Research on adolescent caregiving has documented consistent individual differences due to adolescent gender and birth order. In general, females and older siblings are more likely than males and younger siblings to complete household tasks (Crouter et al., 2001; Gager et al., 2009; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Tsai et al., 2013). We similarly expected that the overall rates of emotional support would be highest among females and older siblings and explored whether these gender and birth order patterns would persist in the same manner on days marked by parental stressors. That is, do females and older siblings continue to be more likely than males and younger siblings to provide emotional support on days of greater need or do all children, regardless of their gender and birth order, contribute when there is an immediate family need?

Stressful or Rewarding Nature of Emotional Caregiving

Our final research aim was to investigate the implications of adolescents’ emotional caregiving for their concurrent and long-term well-being. Within the parentification literature, traditional Western perspectives on adolescents’ engagement in caregiving have typically posited that children’s engagement in activities to care for their family is burdensome for children and can contribute to maladjustment (e.g., Peris et al., 2008; Stein et al., 1999). Some studies have shown that adolescents’ caregiving behaviors place them at risk for adverse psychological symptoms, including higher levels of depressive feelings, internalizing and externalizing behaviors, exhaustion and unhappiness (Gore et al., 1993; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Titzmann, 2012; Williams & Francis, 2010). It is important to note that many studies on parentification include children from stressful home environments, including families experiencing a serious parental illness or chronic marital discord (e.g., Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Peris et al., 2008). Other scholars have found that adolescent caregiving can be associated with adaptive behaviors, including social competence, self-efficacy, and effective coping skills (Kuperminc et al., 2009; Stein et al., 2007; Tompkins, 2006). Additionally, Telzer & Fuligni (2009) found that instrumental support was related to youths’ feelings of family role fulfillment, pointing to the potentially rewarding nature of caregiving that youth experience in lending support to their families. Overall, these mixed findings may reflect the wide spectrum of adolescent caregiving and suggest that the link between adolescents’ support and well-being may depend upon the conditions under which support is provided and to whom adolescents provide support. Additionally, the majority of studies on the negative effects of parentification have included predominantly European American families. Given that Mexican origin families endorse strong values related to familism, these cultural norms and expectations may buffer against the negative impact of caregiving on adolescent well-being.

In the current study, we examined whether adolescents experienced their provision of emotional support as stressful or rewarding. The daily diary design enabled us to capture adolescents’ feelings of distress and family role fulfillment on the same days when they provided support to their families. On the one hand, the inherently stressful circumstances that encourage adolescents to lend support to their families may contribute to feelings of distress. On the other hand, providing emotional support to their families may align with Mexican-American cultural values related to familism and as such, adolescents may feel that they are fulfilling their role as a family member when they provide comfort to their family. Lastly, we assessed the enduring effects on adolescents’ psychological distress by examining whether adolescents’ provision of emotional support is predictive of internalizing and externalizing symptoms one year later.

Research Aims of the Current Study

The overall goal of the study was to examine the conditions under which adolescents provide emotional support to their parents and family members and implications of support provision for adolescent well-being among Mexican-American families. Five key research questions motivated the study: (1) What is the prevalence of adolescents’ emotional support to their parents and to other family members? (2) Do adolescents provide emotional support to their parents and other family members in response to parents’ daily stressors? (3) Is the contingent nature between emotional support and parents’ daily stressors even more pronounced under condition of chronic family hardships (i.e., parents’ economic strain, physical health symptoms)? (4) Does the daily association between parental need and adolescents’ emotional caregiving vary by adolescent characteristics (i.e., family obligation values, generation status, gender, birth order)? and (5) How does emotional caregiving relate to adolescents’ concurrent and future psychological well-being and symptomatology?

Methods

Sample

At the first wave of this two-wave longitudinal study that followed families after one year, 421 ninth and tenth grade students (Mage = 15.03 years, SD = 0.83; 50% males) and their parents (Mage = 41.93 years, SD = 6.77) participated. All participants were of Mexican or Mexican American descent due to selection criteria. The parent was the primary caregiver who self-identified as the adult who spent the most time with the adolescent and knew the most about the adolescent’s daily activities. The majority of primary caregivers were mothers (83%), 13% were fathers and the remaining 4% were grandparents, aunts or uncles. Given that 96% of primary caregivers were mothers or fathers, we use the term “parents” throughout the paper for the sake of simplicity. At Wave 2, 341 families (81%) participated again one year later (M = 1.04 years, SD = 0.11).

Most of the adolescents came from immigrant families: 12.6% were first generation (i.e., adolescent and at least one parent was born in Mexico), 68.6% were second generation (i.e., adolescent was born in the U.S., but at least one parent was born in Mexico) and 18.8% were third generation (i.e., adolescent and parent were born in the U.S.). Both parents were employed in about half (47.5%) of our families. One-third (34.2%) of the primary caregivers worked, whereas 71% of the secondary caregivers were employed. Families included about five members, including the participating adolescent and parent (W1: M = 5.17, SD = 1.57; W2: M = 5.02, SD = 1.86). The majority of the adolescents (W1: 86%, W2: 89%) lived with at least one sibling and about one-quarter to one-third of the adolescents (W1: 28%; W2: 35%) lived with at least one other relative.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from two high schools in the Los Angeles area. Each school possessed significant proportions of students from Latin American backgrounds (62% and 94%). Most students were from lower- to lower-middle class families. In both schools, over 70% of students (72% and 71%) qualified for free and reduced meals, slightly above the average of 65% for Los Angeles County Schools (California Department of Education, 2011; 2012).

Classroom rosters were obtained from the participating schools. Across the first year of the study, a few classrooms were randomly selected each week for recruitment. Research staff visited the classrooms to give a brief presentation about the study to the students. Around the same time, letters were mailed to students’ homes and phone calls were made to parents to determine eligibility and interest. Both the adolescent and their parent had to be willing to participate in the study. The final sample represents 63% of families who were reached by phone and determined to be eligible by self-reporting a Mexican ethnic background. This rate is comparable to other survey and diary studies that followed similar recruitment procedures with Mexican families (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005). About one year after Wave 1, all families were contacted by phone or mail to participate in Wave 2 of the study.

At both waves of the study, interviewers visited the participants’ homes where adolescents completed a self-report questionnaire on their own and parents participated in a personal interview during which the interviewer guided parents through a similar questionnaire and recorded their responses. Questionnaires included items that assessed family background (e.g., household size, education level) and psychological symptoms (e.g., internalizing and externalizing symptoms) and took approximately 45–60 minutes to complete. Next, adolescents and parents were each provided with a 14-day supply of diary checklists to complete every night before going to bed for the subsequent two-week period. Each diary checklist was three pages long and took approximately five to ten minutes to complete. To ensure timely completion of the diary checklists, participants were instructed to fold and seal each completed diary checklist and then stamp the seal with an electronic time stamper. The time stamper imprinted the current date and time and was programmed with a security code so that participants could not alter the correct date and time. Research staff contacted participants by phone during the 14-day period to ensure they were completing the checklists and to answer any questions. Both English and Spanish versions of the questionnaires and diaries were available and interviews with parents were conducted in their preferred language. At Wave 1, three adolescents and 299 (71%) parents completed the study materials (i.e., questionnaires or interviews and diaries) in Spanish. At Wave 2, five adolescents and 249 (73%) parents completed the study in Spanish.

At the end of the two-week period, interviewers returned to the home to collect the diary checklists. Adolescents received $30 and parents received $50 for participating at each wave of the study. Participants were also told that a pair of movie passes would be awarded if inspection of the data indicated that they had completed the diaries correctly and on time. The time-stamper monitoring and incentives resulted in high rates of compliance, with 96% (adolescents) and 95% (parents) of the potential diaries being completed and 86% (adolescents) and 90% (parents) of the diaries being completed on time (i.e., before noon on the following day) at Wave 1. At Wave 2, 88% (adolescents) and 89% (parents) of the potential diaries were completed and 85% (adolescents) and 89% (parents) of the diaries were completed on time.

Measures

Adolescent daily diary measures

On each day of the daily diary reports, adolescents reported on the following behaviors and feelings that they may have experienced. Daily scores from these assessments were used in the analyses.

Provision of emotional support

Adolescents responded to a single item about whether they “provided emotional support (e.g., listening, advice, comfort)” to their parents and to other family members (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000). Emotional support (0 = no; 1 = yes) to parents and other family members were analyzed separately. The validity of this single-item measure of emotional support has been demonstrated in studies indicating that the frequency of such support increases in response to stress experienced by the intended targets of such support (e.g., Gleason, Iida, Shrout & Bolger, 2008).

Psychological distress

Adolescents’ daily distress was assessed with items from the Profile of Mood States (POMS: Lorr & McNair, 1971). Adolescents used a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) to indicate the extent to which they felt distressed which tapped anxious and depressive feelings (seven items: sad, hopeless, discouraged, on edge, unable to concentrate, uneasy, nervous). We averaged across the seven items to create a daily index of psychological distress for each day (W1: M = 1.53, SD = 0.57; W2: M = 1.50, SD = 0.58). This measure had good internal consistency across both waves (W1: α = .84; W2: α = .86).

Family role fulfillment

On a 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) scale, adolescents responded to the statement “How much did you feel like a good family member today?” (W1: M = 5.10, SD = 1.32; W2: M = 5.01, SD = 1.24) (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009).

Parent daily diary measures

Family stressor

Parents indicated whether any of the following six family stressors occurred each day: had a lot of work at home, a lot of family demands, argued with your spouse or partner, argued with another family member, someone in your family did something bad or created a problem, something bad happened to someone else in your family. A dichotomous indicator of daily family stressor was created to assess whether any one of the six stressors occurred each day (0 = no stressor, 1 = 1–6 stressors). Almost all parents (W1: 91%; W2: 93%) reported at least one type of stressor on any given day and overall, parents experienced some type of stressor on about half of the study days (W1: M = 7.10, SD = 4.40; W2: M = 6.76, SD = 4.43).

Adolescent questionnaire measures

Family obligation values

Family obligation values included adolescents’ attitudes toward (1) current assistance to the family (2) respect for the family and (3) future support to the family (Fuligni et al., 1999). Current assistance: twelve items measured how often adolescents felt they should assist with household duties, such as “run errands that the family needs done” and “help take care of your brothers and sisters” (1 = almost never; 5 = almost always). Respect: Seven items measured adolescents’ belief about respecting and following the wishes and expectations of family members, such as “do well for the sake of your family” and “show great respect for your parents” (1= not at all important; 5 = very important). Future support: Six items measured adolescents’ beliefs about providing support and being near their families in the future, such as “help parents financially” and “have your parents live with you when they get older” (1 = not at all important; 5 = very important). Responses were averaged across all items within each subscale. All three subscales were correlated with one another (rs = .45–60, p < .001), therefore we created a general measure of family obligation values by averaging across all three subscales (W1: M = 3.62, SD = 0.65; W2: M = 3.56, SD = 0.63). Overall, this scale had high internal consistencies across both years of the study (W1: α = .90; W2: α = .88).

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms

Adolescents completed the Youth Self-report form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). Adolescents rated items on a 3-point scale (0 = not true of me, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true of me, 2 = true or often true of me). Subscale scores were computed by averaging adolescents’ responses. Internalizing symptoms (31 items) included anxious, somatic and withdrawal symptoms (e.g., “I cry a lot,” “I worry a lot”) (W1: M = 12.20, SD = 8.37; W2: M = 11.46, SD = 7.87). This scale had good internal consistency (W1: α = .88; W2: α = .86). Externalizing symptoms (32 items) included rule breaking and aggressive behaviors (e.g., “argues a lot,” “gets in fights”) (W1: M = 11.84, SD = 7.57; W2: M = 11.37, SD = 7.61) and had high internal consistency (W1: α = .89; W2: α = .88).

Parent questionnaire measures

Economic strain

Parents completed a nine-item scale that assessed the extent to which they experienced difficulties meeting their financial needs over the last three months (Conger et al., 2002). Parents responded to questions such as, “How much difficulty did you have paying your bills” (0 = no difficulty at all; 4 = a great deal of difficulty). Using a 4-point scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (very true), parents also responded to items such as “You had enough money to afford the kind of food you needed.” These latter items were reversed scored and responses were averaged across all the items (W1: M = 2.76, SD = 0.71; W2: M = 2.60, SD = 0.77). The scale had strong internal consistency (W1: α = .90; W2: α = .92).

Physical health symptoms

Parents indicated whether they experienced 12 physical health symptoms in the past two weeks (1 = not at all; 5 = almost everyday), including “headaches,” “dizziness,” “cold sweats,” “low energy,” and “stomachaches or pain” (Resnick et al., 1997). The index of parents’ physical symptoms was calculated by averaging across the 12 items (W1: M = 1.57, SD = 0.53; W2: M = 1.55, SD = 0.50). The scale’s internal consistency was good (W1 & W2 αs = .83).

Adolescent birth order

Parents reported on the ages of the adolescent’s siblings. Adolescents were categorized as being an only (13%), youngest (21.4%), middle (27.5%) or oldest (38.1%) child in the family. Although there were no birth order differences in average levels of emotional support, prior work (e.g., Tsai et al., 2013) has suggested that adolescents who are the youngest child in the family typically provide less support to their families compared to adolescents who are the only, middle or oldest child. This categorization was reflected in our index of birth order (−1 = youngest child; 1 = only, middle or oldest child).

Control variables

Family composition

Parents reported on their current relationship status. The majority of parents (74.6%) were married, remarried or in a domestic relationship with a partner, and these families were considered dual-parent households. This variable was effects coded (−1 = single- parent household, 1 = dual-parent household).

Parents’ education level

Parents reported on their own and their partner’s highest educational attainment by selecting one of the following nine categories: 1 = some elementary school, 2 = completed elementary school, 3 = some junior high school, 4 = completed junior high school, 5 = some high school, 6 = graduated from high school, trade or vocational school, 7 = some college, 8 = graduated from college, 9 = some medical, law or graduate school. Educational status was calculated by averaging both parents’ level of education. The majority of parents (72.8%) had less than a high school education, 13.3% completed high school and 13.7% had more than a high school education.

Results

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses were conducted to examine if families differed as a function of whether they participated in Wave 2. Findings from a series of independent samples t-test indicated that there were no significant differences in any of the key variables (i.e., daily emotional support to parents and family members, daily parental stressors, economic strain, parental physical symptoms, adolescent family obligation values, adolescent gender, household size, parental education) as a function of the family’s Wave 2 participation, ps > .05.

Analytic Strategy

In order to maximize the power to examine daily associations between parents’ report of a family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support, as well as the individual variations in these associations, we combined both waves of the study and conducted a series of three-level hierarchical linear models such that days were nested within waves, which were nested within persons. Preliminary analyses suggested that the provision of emotional support to parents and to other family members did not change over time, therefore we did not estimate how daily- or individual-level associations would vary as a function of time. Collapsing the two waves of data provided up to 28 daily reports and allowed us to make estimates across one year, thereby increasing our ability to detect daily associations between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of support. Adolescents’ emotional caregiving to parents and to other family members did not vary as a function of parents’ education level, therefore we excluded parents’ education level from the rest of the analyses in the paper

To address our first three research questions, three-level hierarchical linear models were estimated using the SAS PROC GLIMMIX (v9.2) procedure given that our main outcome of interest – whether adolescents provided emotional support on any given day – was a binary variable. The estimation procedure accommodates the missing data inherent in repeated-measures designs such as this (e.g., missing a couple of days or the second wave of data collection), therefore all available assessment occasions with complete information about the predictor and criterion variables included in a particular analysis were used. As such, our analytic sample included all 421 families who participated at Wave 1. Separate models were computed to predict adolescents’ provision of emotional support to parents and to other family members. To determine the appropriate variance structure for our models, we conducted a series of likelihood ratio tests to compare the fit of nested models which differed in their variance components. The best fitting model included random intercepts at the wave and person levels and weekday as a random effect at the wave level. We person-centered daily parental family stressor and also included a person-level index of parental family stressor that was averaged across the 14 days at each wave in the models. This ensured that daily-level associations were independent of person-level differences. Family (i.e., economic strain, physical health symptoms) and adolescent (i.e., family obligation values) characteristics were grand-mean centered at each wave. Covariates in the models included weekday, family composition and parental education level.

To address our final research question regarding the implications of adolescents’ provision of emotional support for their well-being, four separate models were conducted to assess whether adolescents’ daily provision of emotional support to parents and to other family members was associated with same-day feelings of psychological distress and family role fulfillment. Given that the outcome variables (i.e., feelings of distress and family role fulfillment) were continuous indices, these models were estimated in SAS PROC MIXED and included the same variance structure as in previous analyses. Lastly, we tested the long-term association between adolescents’ provision of emotional support and their well-being. We calculated the daily level associations between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ emotional caregiving to parents and other family members, separately at Wave 1, and extracted the Empirical Bayes estimates for each individual. These estimates represent the daily contingency between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their families and were used in separate regression models to predict adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms at Wave 2, controlling for Wave 1 symptoms. Given that the outcome of interest is adolescents’ psychological functioning at Wave 2, regression analyses include youth who participated in both Wave 1 and 2 (N = 341).

Daily Prevalence of Emotional Support to Parents and Other Family Members

To address our first research question, two separate models were estimated to assess the overall prevalence of adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their parents and to other family members. Results indicated that on average, adolescents provided emotional support on 12% (b = .12, SE = .01, p <.001) and 13% (b = .13, SE = .01, p < .001) of the days to their parents and other family members, respectively. This translates to an average of 3.36 and 3.64 days of the 28 study days that adolescents provided emotional support to their parents and other family members, respectively. Adolescents were more likely to provide emotional support to other family members on weekends than weekdays, b = −.01, SE = .00, p = .029. Adolescents’ provision of emotional support to parents did not vary by day of the week.

Separate follow-up descriptive analyses were conducted to further explore the distribution of adolescents’ provision of emotional support. About half (46%, 58%) of the adolescents did not provide emotional support to their parents or family members, respectively, on any day throughout the study. A small proportion (14%, 15%) of the adolescents provided emotional support to their parents and other family members, respectively, on at least 8 days (i.e., >1 SD than the average number of days across the sample).

Daily and Chronic Conditions Underlying Emotional Support

Daily stressors

To address our second research question regarding the contingent nature of adolescent support, we examined the daily associations between parents’ report of a family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their parents and to other family members, in separate models. As shown in Model 1a and 1b of Table 1, findings did not indicate significant daily associations between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ emotional caregiving to either parents or other family members. However, results suggested that adolescents with parents who experienced higher levels of family stressors, on average across the study days, are more likely to provide emotional support to both their parents and to other family members. That is, there was a general trend to provide greater emotional support among families in which parents reported greater family stressors across the duration of the study. Additionally, on average, adolescents from dual-parent households were less likely than those from single-parent homes to provide emotional support to both their parents and other family members..

Table 1.

Daily Associations Between Parents’ Report of a Family Stressor and Adolescents’ Emotional Caregiving

| Parents | Other Family Members | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3a | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 3b | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | .10 | .03*** | .10 | .02*** | .10 | .03*** | .13 | .03*** | .12 | .02*** | .11 | .03*** |

| Avg. Family Stressor | .08 | .03** | .06 | .03 | .07 | .03* | 0.06 | 0.03* | .05 | .03 | .05 | .03* |

| Dual-parent household | −.03 | .01* | −.03 | .01** | −.02 | .01* | −0.02 | 0.01* | −.03 | .01** | −.03 | .01* |

| Economic strain | .04 | .01** | .03 | .01* | .04 | .01*** | .04 | .01** | ||||

| Physical symptoms | −.01 | .02 | .00 | .02 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .02 | ||||

| Gender | .01 | .01 | .03 | .01** | ||||||||

| Birth Order | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | ||||||||

| Family obligation values | .05 | .01*** | .04 | .01** | ||||||||

| 1st Generation | .02 | .04 | .04 | .04 | ||||||||

| 2nd Generation | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | .03 | ||||||||

| Daily Family Stressor | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .02 |

| Economic strain | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | ||||

| Physical symptoms | .02 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .03 | .01* | .03 | .01* | ||||

| Gender | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | ||||||||

| Birth Order | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | ||||||||

| Family obligation values | .00 | .01 | .02 | .01* | ||||||||

| 1st generation | −.01 | .03 | .00 | .03 | ||||||||

| 2nd generation | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | .02 | ||||||||

| Weekday | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .00* | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

Note. Daily family stressor was dummy coded (0 = no family stressor and 1 = family stressor occurred) and was person-centered. Weekday, dual-parent household, gender, and birth order were effects coded (−1 = weekend, single-parent household, male, youngest; 1 = weekday, dual-parent household, female, only, middle or oldest child). Generation status was dummy coded with 3rd generation being the control group. Economic strain, physical symptoms and family obligation values were all grand mean centered at each wave.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Given that adolescents did not appear to provide emotional support to their parents on the same days in which their parents reported a family stressor, follow-up analyses were conducted to test whether adolescents may have provided support on the day following the one in which their parent reported having experienced a stressor. Results did not indicate significant daily associations between parental report of a family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to either parents or other family members the following day.

Chronic stressors

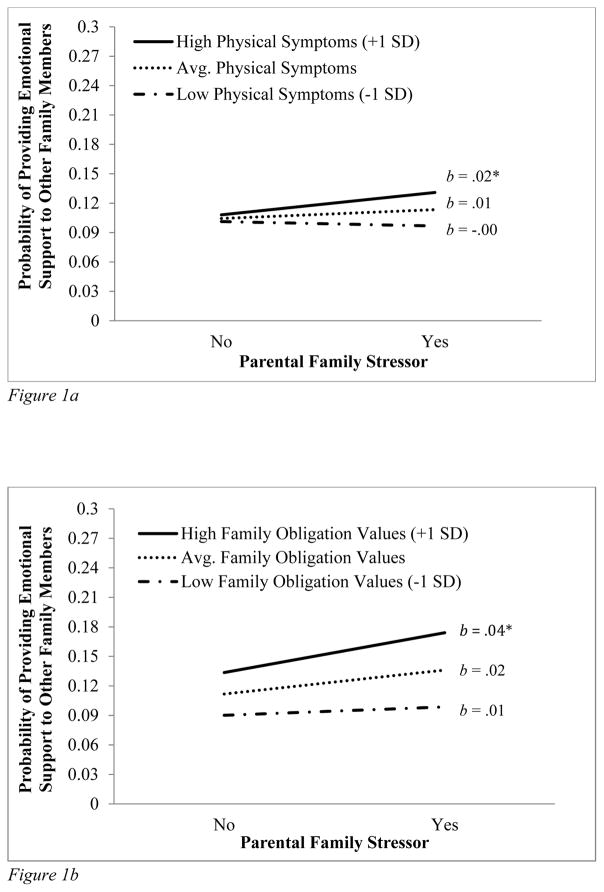

Next, we examined whether the daily association between parents’ familial stressors and adolescents’ provision of emotional support would be more pronounced and contingent upon conditions of chronic parental stressors. To address this research aim, we evaluated individual differences in the daily associations between parents’ report of a family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support, as well as in adolescents’ average levels of emotional caregiving, according to parents’ level of economic strain and physical symptoms. As shown in Models 2a and 2b of Table 1, parents’ physical health symptoms moderated the daily association between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to other family members, but not to their parents (see row labeled “physical symptoms” in the bottom half of the table). In order to interpret the moderating effect, we conducted additional analyses to test the simple slopes for parents with low (−1 SD), average, and high (+1 SD) levels of physical symptoms, which took into account parents’ level of physical symptoms at each wave. Results indicated that the individual slope for parents with high levels of physical symptoms was significant, b = .02, SE = .01, p = .015. As shown in Figure 1a, adolescents with parents who faced higher than average levels of physical symptoms were more likely to provide emotional support to other family members on days when parents reported a family stressor than on days when they did not. Findings suggest that adolescents’ provision of emotional support to other family members is contingent upon the combined effect of daily (i.e., parental family stressor) and chronic (i.e., parental physical symptoms) conditions.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. On days when parents experienced a family stressor, adolescents with parents who experienced high levels of chronic physical symptoms provided emotional support to other family members. The dependent measure ranges from 0–1. * p < .05

Figure 1b. On days when parents experienced a family stressor, adolescents who endorsed high levels of family obligation values provided emotional support to other family member. The dependent measure ranges from 0–1. * p < .05

As indicated in Models 2a & 2b of Table 1, economic strain did not moderate the daily level associations between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support (see row labeled “economic strain” in the bottom half of the table). However, results indicated that on average, economic strain was positively associated with emotional caregiving to both parents and other family members (see row labeled “economic strain” in the top half of the table).

Adolescent Variation in the Provision of Emotional Support

Next, we addressed our fourth research question regarding individual differences in adolescents’ provision of emotional support due to family obligation values, generation status, gender and birth order. We included these individual characteristics in the models to examine whether the daily association between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support, as well as adolescents’ average levels of emotional caregiving, varied as a function of adolescents’ own characteristics. On average, family obligation values were positively associated with adolescents’ emotional caregiving to both their parents and other family members (see row labeled “family obligation values” in the top half of the table). Moreover, as shown in Model 3b of Table 1, adolescents’ family obligation values moderated the daily association between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to other family members, but not to their parents (see row labeled “family obligation values” in the bottom half of the table). In order to interpret this moderating effect, we conducted additional analyses to test the simple slopes for adolescents with low (−1 SD), average, and high (+1 SD) levels of family obligation values. The slope for adolescents with high endorsement of family obligation values was significant, b = .04, SE = .02, p = .024. As shown in Figure 1b, adolescents who had high family obligation values were more likely to provide support to other family members on days when parents reported a family stressor.

No other adolescent characteristics moderated the daily level association between parental stressors and adolescents’ emotional caregiving, and there was little variation in adolescents’ average levels of emotional support, with the exception of gender. On average, females were more likely than males to provide emotional support to other family members (see row labeled “gender” in the top half of the table under Model 3b).

Stressful or Rewarding Nature of Adolescents’ Daily Provision of Emotional Support

The last set of analyses examined the implications of adolescents’ emotional caregiving for their concurrent and long-term psychological well-being and distress in the following year. First, we examined whether adolescents experienced emotional caregiving as stressful or rewarding on the same day on which they provided support. We person-centered adolescents’ provision of emotional support to parents and other family members and included an index of their average levels of support across the 14 days at each wave. Lastly, we included parental daily family stressor and weekday in the model.

As shown in Table 2, on days when adolescents provided emotional support to either their parent or other family members, they did not feel distressed. Rather, adolescents experienced greater feelings of family role fulfillment on days when they provided emotional support to other family members. Results also indicated that averaging across days, the provision of emotional support to both parents and other family members was not associated with overall feelings of distress, but instead, with stronger feelings of family role fulfillment.

Table 2.

Daily Associations Between Provision of Emotional Support and Feelings of Distress and Family Role Fulfillment

| Distress | Family Role Fulfillment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Parents | Other Family Members | Parents | Other Family Members | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 1.50 | 0.03*** | 1.50 | 0.03*** | 5.02 | 0.06*** | 5.00 | 0.06*** |

| Avg. Emotional Support | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.18* | 0.54 | 0.19** |

| Daily Emotional Support | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04* |

| Daily Family Stressor | 0.03 | 0.01* | 0.03 | 0.01* | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Weekday | 0.04 | 0.01*** | 0.04 | 0.01*** | −0.04 | 0.01*** | −0.04 | 0.01*** |

Note. Daily emotional support and family stressor was dummy coded (0 = provided support, no family stressor; 1 = did not provide support, no family stressor occurred) and were person-centered. Weekday was effects coded (−1 = weekend; 1 = weekday).

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Long-term effects of emotional support on well-being

Lastly, we examined the long-term implications of adolescents’ emotional caregiving for their well-being one year later. We utilized the Empirical Bayes estimates, which represents the daily contingency between parents’ report of family stressors and adolescents’ emotional caregiving, to predict adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms separately at Wave 2, controlling for Wave 1 symptoms. Results indicated that the daily contingency between parental family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to either parents or other family members did not predict adolescents’ levels of internalizing (bs = −0.67–0.07, SEs = 1.16–3.53, ps > .05) or externalizing symptoms (bs = −4.32–0.77, SEs = 1.11–3.06, ps > .05) at Wave 2.

We repeated these regression analyses using adolescents’ average levels of emotional support to parents and to other family members, separately, at Wave 1 to predict well-being at Wave 2. Similar to the first set of analyses, overall levels of adolescents’ provision of emotional support were not predictive of internalizing (bs = 0.34–1.40, SEs = 1.46–1.48, ps > .05) or externalizing (bs = −0.17–0.35, SEs = 1.40–1.42, ps > .05) symptoms at Wave 2.

Discussion

The overarching goal of the current study was to uncover the contexts under which Mexican-American adolescents provide emotional support to their families in order to better understand the nature of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors. Although adolescents provided emotional support to their families infrequently, the low occurrence of this behavior can be attributed to the highly contingent nature of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors. Adolescents’ emotional caregiving was linked to parents’ daily and chronic stressors. And although adolescents provided emotional support to their parents and to other family members at similar rates, parents’ experience of a family stressor on a given day was associated with adolescents’ provision of comfort and care, not to their parents, but instead, to other family members. This daily contingency between parents’ familial stressors and adolescents’ caregiving to other family members was especially pronounced among parents who were concurrently facing physical health issues. Additionally, results suggested that the provision of emotional support is a culturally rewarding form of caregiving among Mexican-American youth. Adolescents who endorsed strong family obligation values displayed the highest levels of emotional support to their families and this was especially evident on days marked by greater parental need. Moreover, adolescents derived a sense of family role fulfillment on days that they provided emotional caregiving. There was no evidence that emotional caregiving had concurrent or long-term negative ramifications on adolescents’ psychological well-being.

Supported by the family systems framework and consistent with the parentification literature, the findings from our study provide further evidence that adolescents engage in caregiving behaviors in response to familial need (Crouter et al., 2001; Gager et al., 2009; Tsai et al., 2013). Specifically, we found that for parents who had poorer physical health, the occurrence of a family stressor on a given day prompted adolescents to provide emotional caregiving to a family member, but interestingly, not to their parent. For parents who are concurrently experiencing physical health symptoms, confrontation with an episodic family stressor can be even more overwhelming and interfere with their ability to fulfill their own parenting responsibilities that day (Burton, 2007; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Stein et al., 2007). Consequently, their children step in and assume the responsibility to tend to the needs of other family members, such as their siblings. Adolescents’ emotional care towards another family member can help to ease the tension and strain at home, which in and of itself, can lessen the burden of the parent who may now be more preoccupied by the stressor at hand. Given that some of the stressors (e.g., conflict with someone at home) may have involved another family member, it is possible that adolescents lent their support to the other family member (e.g., sibling, relative) whom they lived with. Thus, it is possible that adolescents were responding to the distress of the other family member as well. Unfortunately, one of the limitations in our study is that we did not collect information on which other family member, if not the parent, the teen provided comfort to. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that adolescents are responsive to the changing family dynamics at home and contribute to the maintenance of family well-being and functioning by lending their support to their family on stressful days.

It is important to note that although we did not find a daily contingency between parents’ family stressors and adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their parents, adolescents provided emotional support both to parents and other family members at similar rates across the study. And despite the absence of this daily contingency between parents’ family stressor and adolescents’ provision of support to their parents, adolescents from families with more frequent occurrences of family stressors, in general, provided emotional support to their parents and to other family members more frequently compared to their peers from families undergoing less stress. These findings indicate that, on average, the provision of emotional support occurs more frequently under the context of stress. The absence of this daily contingency with parents may also suggest that adolescents do not provide emotional support to their parents and other family members on the same days. Family stressors can be taxing on parents’ psychological well-being and time, making them less accessible to their children, and as a result, children may not provide immediate comfort to their parents on that same day. Research on parents’ spillover of work stressors to family life indicates that when parents have a stressful day at work, they become emotionally and socially withdrawn from their families (Repetti, Wang, & Saxbe, 2009). It is possible that rather than providing immediate emotional support to their parents, adolescents are reducing their parents’ distress by other means, such as providing instrumental support (e.g., cooking, cleaning). Indeed, prior work with Mexican-American families showed that adolescents increased their level of instrumental assistance on days when their mother went to work or felt more fatigued (Tsai et al., 2013). This marked distinction regarding whom adolescents provide immediate support to is an interesting family dynamic that reveals the diverse ways that adolescents show concern and care for their families and further highlights the wide spectrum of adolescent caregiving behaviors.

Economic strain was one of the few factors that contributed to the variation in adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their parents. Economic strain was positively linked to adolescents’ overall levels of emotional caregiving to both parents and other family members. Parents facing economic hardships may disclose about family problems to their children, who in turn, become more cognizant of the financial challenges at home (Lehman & Koerner, 2002). Through conversations that parents have with their children about issues related to family finances, children can offer their support, by listening or showing they understand. In conjunction with findings that adolescents’ provision of emotional support to their parents does not occur on the same day in which their parents faced a family stressor, results suggest that adolescents’ emotional support to their parents may not be necessarily linked to a particular stressor that occurred on any given day, but perhaps to their parents’ general level of stress. Altogether, findings suggest that adolescents’ emotional support to parents may be sporadic and largely shaped by chronic familial stressors, whereas adolescents’ emotional support to other family members may be contingent upon both the daily and chronic needs of the family. And although the current study focused on family stressors, it would be valuable for future studies to further examine work-family spillover processes by investigating how parents’ work stressors could also shape adolescents’ caregiving behaviors at home.

Importantly, findings demonstrate that emotional caregiving is a culturally relevant and rewarding activity for Mexican-American youth. Adolescents’ endorsement of family obligation values was associated with higher overall levels of emotional support both to their parents and other family members. On days marked by greater parental need, strong family obligation values boosted adolescents’ emotional support to other family members, providing evidence that emotional caregiving is embedded in values linked to familism, similarly to instrumental support (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009; Tsai et al., 2013). We did not find any generation status differences in the prevalence and contingent nature of adolescents’ provision of emotional support, highlighting that family support is embedded in core cultural values related to familism that are maintained across generations among Mexican origin families (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Marin & Perez-Stable, 1987). Moreover, on days when adolescents provided emotional support to their family members, they experienced elevated feelings of family role fulfillment, suggesting that Mexican-American youth may feel it is their responsibility as a family member to care for their family during times of need. In fact, the response to provide support to other family members, rather than parents, on days of parental need reflects the importance that family obligation values place on the maintenance of cohesive relationships beyond that of the parent-child dyadic bond. Within the cultural context of familism, the provision of emotional support appears to be a personally meaningful and rewarding experience for Mexican-American youth.

Indeed, we did not find evidence that emotional caregiving was concurrently related to youth distress or to maladjustment the following year. Adolescents did not experience feelings of distress on days when they offered emotional support to their families and their provision of emotional care was not indicative of later development of internalizing or externalizing symptomology. These results do not coincide with some of the literature on parentifcation positing that adolescents’ engagement in caregiving is detrimental to their well-being (Gore et al., 1993; Pakenham & Cox, 2012; Williams & Francis, 2010). A large proportion of studies on parentification are based on clinical samples or families undergoing tremendous hardships and dysfunction (e.g., poverty, alcohol abuse); as such, caregiving warranted under these exceptional living conditions is understandably more taxing on children’s psychological well-being (Burton, 2007; Stein et al., 2007). In contrast, parents in our study did not experience family stressors every day, suggesting that adolescents were living in relatively less distressed households. Parental stressors in our study may represent more normative, everyday conflicts and demands at home and therefore, adolescents’ engagement of caregiving under these conditions can have less deleterious effects on their well-being.

Furthermore, the parentification framework is largely based on Western perspectives asserting that children’s adoption of adult responsibilities and knowledge about family problems are developmentally inappropriate (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Jurkovic, 1997). In non-Western cultures, children’s participation in housework, including family caregiving, is viewed as an important aspect of children’s routines that play a central role in the maintenance of family functioning and adolescents’ social development (Goodnow, 1988; Weisner, 2001). In fact, Kuperminc and colleagues (2009) found that Latino adolescents’ perceptions of fairness about their engagement in family caregiving activities buffered the association between caregiving and feelings of distress. Within a cultural milieu that encourages family interdependence and support for one another, the provision of support may be a normative expectation of and activity for children. These findings highlight the importance to situate the examination of children’s behaviors within the larger cultural context in order to understand the relevance and meaning underlying adolescents’ behaviors and their implications for development and adjustment. Future studies should explore whether adolescents from other cultural backgrounds that may not share similarly strong family obligation values will experience their engagement in emotional caregiving under the contexts of everyday family stressors as stressful or rewarding.

Lastly, there was some variation in adolescents’ emotional caregiving due to adolescent gender. Although females were more likely to provide emotional support to other family members, there were no gender differences in their emotional support to parents. A similar family dynamic was evident in another study indicating that although females provided greater overall levels of instrumental support (i.e., the combination of general housework, sibling care, parental assistance), there were no gender differences in adolescents’ instrumental assistance specifically towards parents (Tsai et al., 2013). Perhaps, when there is a specific need or request from parents, they rely equally on their sons and daughters, but when there are more general demands to be met, daughters are more readily than sons to assume responsibility.

Despite key methodological strengths in our study, such as the longitudinal design, utilization of daily diary checklists, and cross-informant reports, there are limitations in our study to acknowledge. Our sample of primary caregivers included mothers, fathers and other relatives, reflecting the diverse family compositions of Mexican-American families. Future research should examine whether the contingent nature of adolescents’ caregiving behaviors may vary as a function of who their primary caregiver may be. Compared to other studies that assessed emotional caregiving via multi-item scales tapping into various forms of caregiving, our measure of emotional support was based on a single item, which could have underestimated the prevalence of emotional caregiving. Nevertheless, the item explicitly asked if adolescents “provided emotional support (e.g., listening, advice, comfort)” to their family, thus allowing participants to make their own inferences about what constitutes emotional support (Bolger et al., 2000). This single-item measure of emotional support also limited our ability to assess the intensity of emotional support, such as how much time adolescents spent comforting their family. It was also not clear whether the contingent nature between parents’ report of a family stressor and adolescents’ provision of emotional support was driven by adolescents’ own initiative to provide support or if a family member sought emotional support from the adolescent. It would be important for future studies to examine the underlying motivations of adolescents’ caregiving in order to better understand adolescents’ awareness and response to family stress. For example, studies can evaluate whether adolescents actually perceived a family member to be in distress and examine how adolescents’ emotional response to family stressors may motivate them to provide comfort to a family member. Lastly, it would have been valuable to have parental perspectives on the emotional support they received from their child.

Conclusion

Adolescents’ engagement in family caregiving encompasses a spectrum of behaviors that can occur in a variety of family contexts. Traditional Western perspectives on adolescent caregiving have typically posited that assuming responsibilities towards the maintenance of family functioning and well-being is burdensome and maladaptive for children. The current study with Mexican-American families offers a different perspective illustrating that within a cultural milieu that promotes family solidarity and interdependence, engagement in emotional caregiving is part of the family’s cultural script to respond to the needs of the family, and is consequently experienced as a rewarding behavior. Emotional caregiving was most prevalent among adolescents who internalized strong family obligation values and was associated with elevated feelings of family role fulfillment, suggesting that emotional caregiving is embedded in cultural values and family routines that reinforce adolescents’ feelings of family responsibility and membership. Future studies should continue to examine adolescents’ caregiving to their families across diverse ethnic groups to better understand how cultural contexts shape adolescents’ caregiving and how these behaviors contribute to adolescents’ social and psychological development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD057164). Many thanks to the families who participated in the study and to Thomas S. Weisner for his assistance with the study design and valuable feedback on prior drafts of this article.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavioral checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(6):953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L. Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2007;56(4):329–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education. School summary data. 2011, 2012 Retrieved from http://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Head MR, Bumpus MF, McHale SM. Household chores: Under what conditions do mothers lean on daughters? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2001;94:23–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner LM, Orellana MF, Jiménez R. “It’s one of those things that you do to help the family”: Language brokering and the development of immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(5):515–543. doi: 10.1177/0743558408317563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Earley L, Cushway D. The parentified child. Clinical and Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:163–178. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70(4):1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, Sanchez LA, Demaris A. Whose time is it?: The effect of employment and work/family stress on children’s housework. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30(11):1459–1485. doi: 10.1177/0192513x09336647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MEJ, Iida M, Shrout PE, Bolger N. Receiving support as a mixed blessing: Evidence for dual effects of support on psychological outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:824–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow JJ. Children’s household work: Its nature and functions. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(1):5–26. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colten ME. Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1993;3(2):101–125. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0302_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM, Marotta SA, Lanthier RP. Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: A retrospective exploratory study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;17(5):693–705. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9184-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic GJ. Lost childhoods: The plight of the parentified child. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc GP, Jurkovic GJ, Casey S. Relation of filial responsibility to the personal and social adjustment of Latino adolescents from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(1):14–22. doi: 10.1037/a0014064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman SJ, Koerner SS. Family financial hardship and adolescent girls’ adjustment: The role of maternal disclosure of financial concerns. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;48(1):1–24. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2002.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorr M, McNair DM. The Profle of Mood States Manual. San Francisco, CA: Educational and Institutional Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel AG, Contreras JM. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Journal of Behavioral Science. 2003;25:312–3330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TJ, Luthar SS. Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden amogn children living in urban poverty. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:267–281. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267. doi:10.10370002-9432.77.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Cox S. The nature of caregiving in children of a parent with multiple sclerosis from multiple sources and the associations between caregiving activities and youth adjustment overtime. Psychology & Health. 2012;27(3):324–346. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.563853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Emery RE. Marital conflict and support seeking by parents in adolescence: Empirical support for the parentification construct. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(4):633–642. doi: 10.1037/a0012792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti R, Wang SW, Saxbe D. Bringing it all back home: How outside stressors shape families’ everyday lives. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(2):106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01618.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, … Shew M. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of American Medical Assocation. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin BV, Perez-Stable E. Hispanic familism and acculturaion: What chagnes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lester P. Impact of parentification on long-term outcomes among children of parents with HIV/AIDS. Family Process. 2007;46(3):317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. Daily family assistance and the psychological well-being of adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1177–1189. doi: 10.1037/A0014728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titzmann PF. Growing up too soon? Parentification among immigrant and native adolescents in Germany. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41(7):880–893. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins TL. Parentification and maternal HIV infection: Beneficial role or pathological burden? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;16(1):108–118. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9072-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KM, Telzer EH, Gonzales NA, Fuligni AJ. Adolescents’ daily assistance to the family in response to maternal need. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75:964–980. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(4):512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Children investing in their families: The importance of child obligation in successful development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2001;2001:77–84. doi: 10.1002/cd.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch GG, Constatine LL. Systems theory. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Francis SE. Parentification and psychological adjustment: Locus of control as a moderating variable. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2010;32(3):231–237. doi: 10.1007/s10591-010-9123-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]