The scarcity of oxidants in the ancient oceans may have inhibited phosphorus recycling, stifling the growth of the biosphere.

Abstract

Phosphorus sets the pace of marine biological productivity on geological time scales. Recent estimates of Precambrian phosphorus levels suggest a severe deficit of this macronutrient, with the depletion attributed to scavenging by iron minerals. We propose that the size of the marine phosphorus reservoir was instead constrained by muted liberation of phosphorus during the remineralization of biomass. In the modern ocean, most biomass-bound phosphorus gets aerobically recycled; but a dearth of oxidizing power in Earth’s early oceans would have limited the stoichiometric capacity for remineralization, particularly during the Archean. The resulting low phosphorus concentrations would have substantially hampered primary productivity, contributing to the delayed rise of atmospheric oxygen.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphorus (P) availability is thought to dictate the amount of primary productivity that can be sustained in the oceans on geologic time scales (1, 2). Estimating P concentrations in the ocean across Earth’s history is thus critical for understanding the growth of the biosphere and the evolution of major biogeochemical cycles—namely, the rise of atmospheric oxygen, which requires substantial burial of organic carbon generated via oxygenic photosynthesis. Multiple proxies have been used to reconstruct P levels, including the P content of iron (Fe) oxide–rich sedimentary rocks (3–5) and marginal marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks (6). Although deriving quantitative assessments of P levels from these records has been notoriously difficult [for example, Bjerrum and Canfield (3) and Konhauser et al. (7)], recent work is beginning to converge on a low P ocean [<20% modern concentrations; modern, ~2 μM; (1, 2)], persisting in the Archean and perhaps through the Proterozoic (5, 6). The favored mechanism for P depletion in the Precambrian ocean is scavenging of P from the water column by incorporation into ferrous minerals or by adsorption onto Fe oxides (3, 5, 6). However, these models have not accounted for potential “upstream” throttles that could have kept P concentrations low without any influence of Fe scavenging. Here, we propose a new mechanism for maintaining low P: limited recycling of P in an oxidant-poor ocean.

The bioavailable P supply of the ocean derives almost entirely from riverine inputs, making P a scarce nutrient relative to carbon and nitrogen, which can be fixed from atmospheric sources (2). The modern riverine flux of bioavailable P is very small [~2 × 1012 g/year; (8)] compared to the amount annually used by the marine biosphere [~1200 × 1012 g/year; (8)]. This large discrepancy between supply and demand is sustained by the efficient recycling of P within the ocean. After the P in the surface ocean is exhausted during primary production, the remineralization of sinking biomass releases P back into the marine environment. This recycling increases the residence time of P in the ocean. As water masses mature in the deep ocean, they accumulate nutrients regenerated through biomass recycling and ultimately deliver these nutrients to the continental shelves via upwelling, enabling high rates of biological productivity. In the modern ocean, ~80 to 90% of primary productivity gets remineralized in the photic zone (upper, ~200 m; fig. S1), with most of the remainder being oxidized at depth or in marine sediments (9, 10). Only a very small percentage (≪1%) of net primary productivity (and its associated P) escapes remineralization and is ultimately buried in marine sediments. Thus, the magnitude of the P recycling flux has probably always dwarfed riverine inputs, even if early Precambrian riverine fluxes were an order of magnitude higher than today (11).

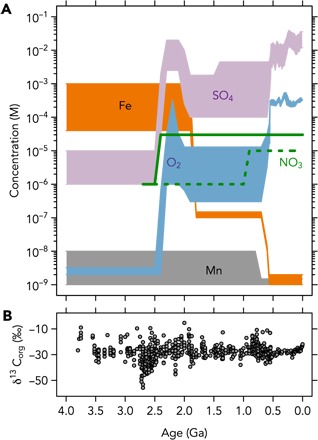

A critical difference between Precambrian and modern oceans is the availability of electron acceptors needed for the oxidation of biomass. In the oxygenated modern ocean, most organic matter degradation occurs aerobically (12). Even when localized water masses or sedimentary pore waters become anoxic, there is an ample supply of anaerobic electron acceptors [for example, sulfate (SO42−)] to fuel biomass decomposition (13). Before the establishment of oxidizing conditions at Earth’s surface, it is conceivable that the recycling of organic matter was limited by a scarcity of electron acceptors. Inhibited organic remineralization would mean that a greater proportion of sinking organic matter was preserved in marine sediments (that is, higher burial efficiency). However, the limited regeneration of P in this system might maintain low steady-state P concentrations in the deep ocean and upwelling waters, which would ultimately limit net primary productivity, total organic burial, and oxygenesis. We quantitatively explored this hypothesis by compiling estimates of the paleoconcentrations of the major electron acceptors in seawater (Fig. 1A) and stoichiometrically calculating the concentration of P that could have been maintained throughout Earth’s history.

Fig. 1. Redox evolution of the Earth.

Compilations of (A) electron acceptor availability in seawater and (B) sedimentary organic carbon isotope record. The prevalence of extremely negative δ13C values from ~2.8 to 2.5 Ga has been interpreted by some as a signal of widespread methanogenesis [(90) and references therein].

The rationale for this approach comes from the observation that, in the modern ocean, the concentrations of P and oxygen in surface (Ps and O2s) and deep (Pd and O2d) waters can be stoichiometrically equated using the chemical equation of aerobic decomposition and concomitant liberation of P (fig. S2) (12). This is based on the premise that all P in deep waters (Pd) derives from either (i) the release of P during the oxidation of organic matter or (ii) downwelling of nutrient-rich waters (Ps) from high latitudes that is driven by thermohaline circulation. Thus, Pd can be calculated as shown in Eq. 1, where is the stoichiometric coefficient of the liberation of P from organic matter during aerobic respiration [120 to 200; average, 169; (12, 14)]

| (1) |

This equation has been validated for the modern ocean (12) and has also been used to constrain Precambrian oxygen levels (14). It is therefore a reasonable approach to track first-order trends in ocean chemistry.

We modified this equation to explore the possibility of limited P recycling in the Precambrian (see the Supplementary Materials for detailed description). First, we added the contribution of anaerobic respiration pathways in descending order according to the thermodynamic favorability of the corresponding metabolic reaction (15). Stoichiometric coefficients (ri) were taken from Canfield et al. (16). To assess the contribution of organic disproportionation reactions (that is, methanogenesis and fermentation), we derived an upper limit () using modeled methanogenesis rates for the Precambrian. Scaling the modern rate of methane production in marine sediments [20 Tmol/year; (17)] to the rate modeled for the late Archean [96 Tmol/year; (18)]—a time that may have had exceptionally vigorous methanogenesis (Fig. 1B)—suggests that disproportionation of organic matter likely never contributed more than 0.1 μM of additional P recycling (see the Supplementary Materials for detailed calculation). We conservatively applied this value to all of our Precambrian calculations. The modified equation becomes

| (2) |

which can be simplified by combining the total contribution of P recycling into a single term (Pr) such that

| (3) |

We solved for Pr using published estimates for electron acceptor availability in the surface oceans (Xs; Fig. 1A), assuming that all electron acceptors were quantitatively consumed (that is, Xd = 0). Our estimates are conservative and likely overestimate total P regeneration for several reasons. First, if SO42− had been quantitatively consumed at all times, then net isotopic fractionations in δ34S as recorded in marine sediments should be minimal as a result of quantitative mass transfer, in contrast to what is observed in the Proterozoic [although not in the Archean; (14)]. Second, we did not account for other reactions such as CH4 or H2 oxidation that can consume electron acceptors without liberating P. Last, unlike the other electron acceptors in this model, manganese (Mn) and Fe are insoluble in their oxidized states. Upon reaching the ocean, Mn and Fe oxides tend to settle out of the water column, restricting their P recycling contributions to localized sedimentary settings, where liberated P is often trapped by diagenetic P minerals such as carbonate fluorapatite (CFA). In addition, their oxidizing power is limited to particle surfaces, meaning that their true oxidative capacity is considerably lower than is suggested by simple bulk concentrations (see the Supplementary Materials for further discussion). For these reasons, we are likely overestimating the contribution of Mn and Fe in these calculations. Fe3+ and SO42− can be regenerated during biogeochemical cycling within the ocean and thus can be used multiple times to recycle P; however, these reoxidation pathways consume another oxidant that then becomes unavailable, and hence, there is no net change in P regeneration. Thus, we stress that these calculations are conservative and, if they err, tend to overestimate total Pr.

We also considered potential variability of the Redfield C/P ratio through time because the stoichiometric coefficient (ri) scales with the C/P ratio of the degraded biomass. Although today there is a fairly conserved C/P ratio of ~106 in marine phytoplankton (19), it has been proposed that this ratio was substantially higher in the low-P Precambrian ocean (6). Laboratory cultures have demonstrated flexibility in cyanobacterial C/P ratios from ~106 to >500 as a function of P availability (20). We therefore explored three cases of constant (106), moderately enriched (400), and highly enriched (1000) C/P ratios to generate a comprehensive range of outputs.

To constrain Ps, we considered two endmember scenarios: (i) Through thermohaline circulation and upwelling, the maximum P content of the surface ocean (Ps) is equal to the P contained in deep waters that is initially set by biomass remineralization (Ps = Pr) (12). (ii) Alternatively, thermohaline circulation may be suppressed, in particular during intervals in the Precambrian that lack geological evidence of glaciations. In this case, Ps = 0.

RESULTS

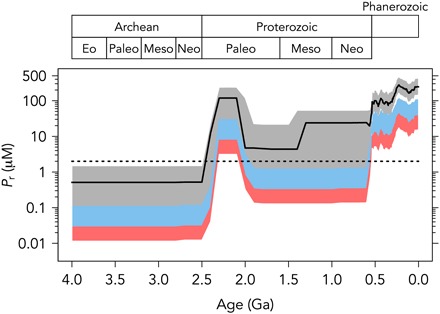

Our calculations reveal a significant increase in the capacity for P recycling (Pr) as the Earth’s surface environment evolved from a reduced state to an oxidized state, in particular during the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) at ~2.4 billion years ago (Ga) (21), when marine sulfate levels increased markedly (Fig. 2). The modern ocean has a vast excess of oxidizing capacity that is not exhausted during the recycling of sinking biomass. In other words, the amount of organic matter remineralization that occurs in the modern ocean is not limited by the total abundance of electron acceptors but rather by the kinetics of organic degradation, sorption of organics onto mineral surfaces, polymerization reactions leading to the formation of recalcitrant organic matter, and sedimentation rates (10, 13, 22). In contrast, our calculations suggest that the remineralization of organic matter could have been inhibited in the Archean simply due to the limited availability of electron acceptors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Total possible P recycling through geologic time.

Black line indicates preferred values. Gray shaded area is uncertainty envelope for C/P ratios of 106:1. Blue shaded region is uncertainty envelope for C/P ratios of 400:1; red shaded region corresponds to C/P of 1000:1. Dotted line shows modern concentration of P in the deep ocean and upwelling water (~2 μM).

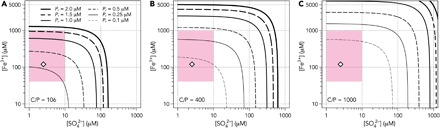

In the absence of appreciable dissolved oxygen, the recycling of biomass in the Archean would have relied heavily on respiration of Fe3+ and SO42− (Fig. 1). Recent estimates (23, 24) place Archean [SO42−] at <10 μM, meaning that sulfate reduction would have contributed no more than 0.2 μM to Pr (Fig. 3). Levels of dissolved Fe3+ may have been as high as 1 mM if Fe2+ levels were constrained by greenalite solubility (25) and if all Fe2+ underwent oxidation to bioavailable Fe3+. In this scenario, iron reduction could theoretically have contributed up to 1.5 μM to Pr (Fig. 3A). However, this upper limit is unlikely for several reasons. First, a large fraction of Fe3+ may have settled out of the water column as solid particles without being used for organic remineralization. Second, siderite saturation may have kept Fe2+ levels below 120 μM (26), which would push Pr to <0.4 μM. Last, if microbial C/P stoichiometry shifted to higher levels under pervasive nutrient stress in the Precambrian (6), the effect of limited P recycling would become considerably more severe (Fig. 3, B and C). Furthermore, episodes of high Fe input into the ocean could have exerted a negative feedback on P availability. When Fe input was high, it may have allowed for a high degree of P recycling by Fe3+ respiration, but at the same time, high levels of Fe2+ in the water column could subsequently have scavenged liberated P. The net burden for sustaining a large reservoir of dissolved P may thus have rested primarily on microbial sulfate reducers (maximum Pr < 0.2 μM). As a conservative estimate, we proceed with a value of <0.4 μM for Pr to allow for some contribution of Fe3+ respiration (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Total possible Archean P recycling as a function of ferric iron and sulfate availability.

Calculations are presented for C/P ratios of (A) 106, (B) 400, and (C) 1000. Diamond shows preferred values; pink shaded region shows published range of estimates for Archean seawater. Ferric iron reduction could have played a large role in P recycling if bioavailable Fe3+ levels were ~1 mM, but this scenario is very unlikely (discussed in the text). Elevated C/P ratios in primary producers would have severely impeded P recycling in all scenarios.

If we now add our most conservative estimate of P dissolved in surface waters (Ps), our maximum calculated Pd value is <0.8 μM for the Archean. This is <40% of modern values and is likely an overestimate for the reasons outlined above. Actual concentrations could have been substantially lower, particularly if bacteria adjusted their C/P ratios to higher values (Fig. 3), or if thermohaline circulation was less effective than today. These upper limits agree well with recent estimates of Archean P concentrations [0.04 to 0.38 μM; (5, 6)].

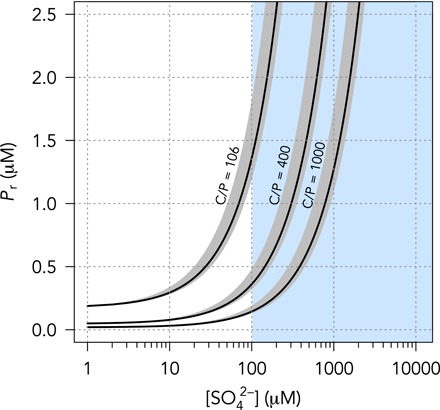

However, our model allows for high P levels in the Proterozoic after growth of the seawater sulfate reservoir (Fig. 4), in contrast to recent proxy evidence (6). There are a few possible solutions to this disagreement: (i) P recycling may have been operating more effectively in the Proterozoic, but Fe scavenging depleted this recycled P and became the most significant sink for P, thus maintaining low P levels until the latest Proterozoic. (ii) Alternatively, P recycling may still have been inhibited if the marine sulfate reservoir was not quantitatively utilized, such that the full oxidation potential was not exploited. This would be consistent with an increase in the spread of δ34S values of Proterozoic sedimentary sulfides, which indicate nonquantitative sulfate reduction in the marine environment (14). (iii) Last, if C/P ratios were significantly elevated above modern values, then even moderate P recycling could still have kept the P reservoir small in the Proterozoic (Fig. 4). It is therefore conceivable that electron acceptor limitation for P liberation extended into the Proterozoic eon.

Fig. 4. Total possible Proterozoic P recycling as a function of sulfate availability.

Blue shaded region shows range of published estimates for Proterozoic sulfate concentrations. An increase in seawater sulfate levels after the GOE would have considerably increased the capacity for P recycling, although high C/P ratios could still have kept P levels low at the lower end of published estimates.

DISCUSSION

These results carry several important implications. First, oxidant-limited recycling of P, rather than scavenging by Fe minerals, probably exerted the major control on P availability in the Archean, because secondary P-bearing minerals cannot form if P remains bound to organic matter. However, Fe scavenging could have become the major P sink in the Proterozoic if P recycling became more efficient (Figs. 2 and 4). This would require that electron acceptors were nearly fully exploited, which is not the case today. Our model does not require higher-than-modern organic carbon concentrations in Archean sedimentary rocks but instead a relatively larger proportion of preservation of primary productivity, which would, in turn, have been suppressed with a lower P availability. The severity of this P scarcity imposed by limited biomass recycling increases substantially if bacterial C/P ratios were higher in the Precambrian (Figs. 3 and 4). In such scenarios, the formation of authigenic P-bearing mineral phases (for example, CFA) may have been inhibited by the lower P input to marine sediments (6).

Second, our results suggest that in the Archean, microbial iron and sulfate reduction played an essential role in sustaining biological productivity by conducting the vast majority of P recycling within the ocean system (Fig. 3). The contributions of these two pathways may have been comparable despite a greater abundance of Fe3+ than SO42− in Archean seawater, because sulfate reduction involves a transfer of eight electrons compared to one electron in iron reduction, meaning that more P can be liberated per molecule. Before the onset of significant oxidative continental weathering (27), the major source of SO42− to the ocean would have been photolysis of volcanic SO2 (28). Our results thus highlight the potentially important role of volcanism in sustaining a significant biosphere on an anoxic planet by sourcing SO42− to the ocean where it could contribute to biomass recycling. In addition, the contribution of iron reduction to P recycling may have been sensitive to secular changes in heat flow and pulses in hydrothermal Fe inputs. These results thus illustrate another strong linkage between biological and planetary evolution.

Last, our proposed mechanism for low Archean P levels may help explain the delay between the earliest compelling evidence of oxygenic photosynthesis at ~3.0 Ga (29) and the accumulation of atmospheric oxygen during the GOE (21). It has long been recognized (30) that under near-modern rates of primary productivity, it is difficult to satisfy redox balance at Earth’s surface while keeping atmospheric oxygen levels extremely low (31). However, if suppressed recycling of biomass limited the P supply, then lower rates of primary productivity would alleviate the troubles with the Archean redox budget due to diminished biospheric oxygen production. This P-limited state could have been exited as incipient oxidation began on Earth’s surface, delivering sulfate to the marine environment (27), thus increasing productivity and oxygenesis, culminating in the GOE.

METHODS

We modified the box model approach used by Sarmiento et al. (12) to calculate dissolved P concentrations in the Precambrian oceans. This model relates deep (O2d) and surface (O2s) ocean oxygen concentrations by recognizing that their difference is equivalent to the amount of oxygen consumed during the oxidation of sinking organic matter, and that this can be stoichiometrically equated to the difference in surface and deep ocean P levels (Pd − Ps). This relationship can thus be expressed

| (4) |

where r is the stoichiometric coefficient of the liberation of P from biomass during aerobic remineralization (see model schematic in fig. S2). If P were not selectively remineralized during organic degradation, then r would approximately equal the Redfield C/P ratio of primary producers (for example, 106) due to the 1:1 O2/C stoichiometry of aerobic respiration. However, it is known that P is selectively released from organic matter during decomposition reactions (32), meaning that r is greater than the Redfield C/P ratio. The value of r has typically been estimated at 169 (12, 14, 33), although observations range from 120 to 200 in the modern ocean (34). We therefore used 169 as our preferred value and explored the range from 120 to 200 to establish our confidence interval.

Equation 4 can then be used to predict deep ocean oxygen concentrations if all other parameters are known. In order for this model to accurately capture the dynamics of the modern ocean, however, it is necessary to use O2s and Ps values from high-latitude waters, because these water masses currently feed the deep ocean (12). Failure to do so will generate very low (or negative) O2d values, because some of the P in the deep ocean today derives from these downwelling nutrient-rich waters. Solving the equation with published P concentrations [Pd = 1.7 to 2.3 μM (2, 5, 12, 35); Ps = 0.7 to 1.24 μM (12, 35)] and using an O2s value of 325 μM—representative of high-latitude surface waters (12)—yields an O2d value of approximately 156 μM (confidence interval, 110 to 185 μM), which is in good agreement with oceanographic observations (12, 36).

To instead solve for deep ocean P concentrations, the equation can be rearranged

| (5) |

The amount of P in the deep ocean is thus shown to be equivalent to the amount sourced from nutrient-rich downwelling waters plus the amount liberated during biomass recycling.

We further modified the box model to include additional electron acceptors representing the most globally significant anaerobic metabolic pathways (fig. S2B). Although these pathways have a relatively minor role in P regeneration in the modern ocean, the reducing oceans of the Precambrian would have featured predominantly anaerobic microbial metabolisms (see main text for discussion).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Buick for formative discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. We also thank associate editor J. Middelburg, as well as C. Reinhard and two anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved this paper. Funding: This work was supported by NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1256082 to M.A.K., a NASA Postdoctoral Fellowship to E.E.S., NASA Exobiology grant NNX16AI37G, and NASA Astrobiology Institute grant NNA13AA93A. Author contributions: M.A.K. and E.E.S. developed the idea. M.A.K. conducted the calculations and wrote the paper, with substantial contributions from E.E.S. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/11/eaao4795/DC1

Supplementary Text

fig. S1. Estimated annual fluxes of C, N, P, and O2 consumption as a function of depth.

fig. S2. Box model schematic.

fig. S3. P concentrations and organic C/P ratios in marginal marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.W. S. Broecker, T.-H. Peng, Z. Beng, Tracers in the Sea (Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory, Columbia University, 1982). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyrrell T., The relative influences of nitrogen and phosphorus on oceanic primary production. Nature 400, 525–531 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjerrum C. J., Canfield D. E., Ocean productivity before about 1.9 Gyr ago limited by phosphorus adsorption onto iron oxides. Nature 417, 159–162 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planavsky N. J., Rouxel O. J., Bekker A., Lalonde S. V., Konhauser K. O., Reinhard C. T., Lyons T. W., The evolution of the marine phosphate reservoir. Nature 467, 1088–1090 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones C., Nomosatryo S., Crowe S. A., Bjerrum C. J., Canfield D. E., Iron oxides, divalent cations, silica, and the early earth phosphorus crisis. Geology 43, 135–138 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhard C. T., Planavsky N. J., Gill B. C., Ozaki K., Robbins L. J., Lyons T. W., Fischer W. W., Wang C., Cole D. B., Konhauser K. O., Evolution of the global phosphorus cycle. Nature 541, 386–389 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konhauser K. O., Lalonde S. V., Amskold L., Holland H. D., Was there really an Archean phosphate crisis? Science 315, 1234 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.W. H. Schlesinger, E. S. Bernhardt, Biogeochemistry: An Analysis of Global Change (Academic Press, ed. 3, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin J. H., Knauer G. A., Karl D. M., Broenkow W. W., VERTEX: Carbon cycling in the northeast Pacific. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 34, 267–285 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerson S., Hedges J. I., Processes controlling the organic carbon content of open ocean sediments. Paleoceanography 3, 621–634 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao J., Sverjensky D. A., Hazen R. M., A model for late Archean chemical weathering and world average river water. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 457, 191–203 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarmiento J. L., Herbert T. D., Toggweiler J. R., Causes of anoxia in the world ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2, 115–128 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 13.S. E. Calvert, T. F. Pedersen, in Organic Matter: Productivity, Accumulation, and Preservation in Recent and Ancient Sediments, J. K. Whelan, J. W. Farrington, Eds. (Columbia Univ. Press, 1992), pp. 231–263. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canfield D. E., A new model for Proterozoic ocean chemistry. Nature 396, 450–453 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Froelich P. N., Klinkhammer G. P., Bender M. L., Luedtke N. A., Heath G. R., Cullen D., Dauphin P., Hammond D., Hartman B., Maynard V., Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: Suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43, 1075–1090 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canfield D. E., Jorgensen B. B., Fossing H., Glud R., Gundersen J., Ramsing N. B., Thamdrup B., Hansen J. W., Nielsen L. P., Hall P. O., Pathways of organic carbon oxidation in three continental margin sediments. Mar. Geol. 113, 27–40 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeburgh W. S., Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 486–513 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izon G., Zerkle A. L., Williford K. H., Farquhar J., Poulton S. W., Claire M. W., Biological regulation of atmospheric chemistry en route to planetary oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E2571–E2579 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A. C. Redfield, B. H. Ketchum, F. A. Richards, The influence of organisms on the composition of sea-water, in The Sea, M. N. Hill, Ed. (Interscience Publishers, 1963), vol. 2, pp. 26–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White A. E., Spitz Y. H., Karl D. M., Letelier R. M., Flexible elemental stoichiometry in Trichodesmium spp. and its ecological implications. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1777–1790 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekker A., Holland H. D., Wang P.-L., Rumble D. III, Stein H. J., Hannah J. L., Coetzee L. L., Beukes N. J., Dating the rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 427, 117–120 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedges J. I., Keil R. G., Sedimentary organic matter preservation: An assessment and speculative synthesis. Mar. Chem. 49, 81–115 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowe S. A., Paris G., Katsev S., Jones C., Kim S.-T., Zerkle A. L., Nomosatryo S., Fowle D. A., Adkins J. F., Sessions A. L., Farquhar J., Canfield D. E., Sulfate was a trace constituent of Archean seawater. Science 346, 735–739 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhelezinskaia I., Kaufman A. J., Farquhar J., Cliff J., Large sulfur isotope fractionations associated with Neoarchean microbial sulfate reduction. Science 346, 742–744 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosca N. J., Guggenheim S., Pufahl P. K., An authigenic origin for Precambrian greenalite: Implications for iron formation and the chemistry of ancient seawater. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 128, 511–530 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.H. D. Holland, Geologic history of seawater, in Treatise on Geochemistry, H. Elderfield, Ed. (Elsevier, 2004), vol. 6, pp. 583–625. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stüeken E. E., Catling D. C., Buick R., Contributions to late Archaean sulphur cycling by life on land. Nat. Geosci. 5, 722–725 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farquhar J., Bao H. M., Thiemens M., Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289, 756–758 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Planavsky N. J., Asael D., Hofmann A., Reinhard C. T., Lalonde S. V., Knudsen A., Wang X., Ossa Ossa F., Pecoits E., Smith A. J. B., Beukes N. J., Bekker A., Johnson T. M., Konhauser K. O., Lyons T. W., Rouxel O. J., Evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis half a billion years before the Great Oxidation Event. Nat. Geosci. 7, 283–286 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30.H. D. Holland, The Chemical Evolution of the Atmosphere and Oceans (Princeton Univ. Press, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasting J. F., What caused the rise of atmospheric O2? Chem. Geol. 362, 13–25 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark L. L., Ingall E. D., Benner R., Marine phosphorus is selectively remineralized. Nature 393, 426 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi T., Broecker W. S., Langer S., Redfield ratio based on chemical data from isopycnal surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 90, 6907–6924 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer G., Biogeochemical cycling in the global ocean: 2. New production, Redfield ratios and remineralisation in the organic pump. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 3723–3745 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levitus S., Conkright M. E., Reid J. L., Najjar R. G., Mantyla A., Distribution of nitrate, phosphate and silicate in the world oceans. Prog. Oceanogr. 31, 245–273 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 36.T. P. Boyer, J. I. Antonov, H. E. Garcia, D. R. Johnson, R.A. Locarnini, A.V. Mishonov, M. T. Pitcher, O. K. Baranova, World Ocean Database 2005, S. Levitus, Ed. (Government Printing Office, 2006); www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/WOA05/pr_woa05.html.

- 37.Pavlov A. A., Kasting J. F., Mass-independent fractionation of sulfur isotopes in Archean sediments: Strong evidence for an anoxic Archean atmosphere. Astrobiology 2, 27–41 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson S. L., Kump L. R., Kasting J. F., Quantifying the areal extent and dissolved oxygen concentrations of Archean oxygen oases. Chem. Geol. 362, 35–43 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bekker A., Holland H. D., Oxygen overshoot and recovery during the early Paleoproterozoic. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317–318, 295–304 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardisty D. S., Lu Z., Planavsky N. J., Bekker A., Philippot P., Zhou X., Lyons T. W., An iodine record of Paleoproterozoic surface ocean oxygenation. Geology 42, 619–622 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kipp M. A., Stüeken E. E., Bekker A., Buick R., Selenium isotopes record extensive marine suboxia during the Great Oxidation Event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 875–880 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Planavsky N. J., Reinhard C. T., Wang X., Thomson D., McGoldrick P., Rainbird R. H., Johnson T., Fischer W. W., Lyons T. W., Low Mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635–638 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cole D. B., Reinhard C. T., Wang X., Gueguen B., Halverson G. P., Gibson T., Hodgskiss M. S. W., McKenzie N. R., Lyons T. W., Planavsky N. J., A shale-hosted Cr isotope record of low atmospheric oxygen during the Proterozoic. Geology 44, 555–558 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang S., Wang X., Wang H., Bjerrum C. J., Hammarlund E. U., Costa M. M., Connelly J. N., Zhang B., Su J., Canfield D. E., Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 1731–1736 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sperling E. A., Wolock C. J., Morgan A. S., Gill B. C., Kunzmann M., Halverson G. P., Macdonald F. A., Knoll A. H., Johnston D. T., Statistical analysis of iron geochemical data suggests limited late Proterozoic oxygenation. Nature 523, 451–454 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berner R. A., GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5653–5664 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stüeken E. E., Kipp M. A., Koehler M. C., Buick R., The evolution of Earth’s biogeochemical nitrogen cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 160, 220–239 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stüeken E. E., Buick R., Guy B. M., Koehler M. C., Isotopic evidence for biological nitrogen fixation by molybdenum-nitrogenase from 3.2 Gyr. Nature 520, 666–669 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godfrey L. V., Falkowski P. G., The cycling and redox state of nitrogen in the Archaean ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2, 725–729 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garvin J., Buick R., Anbar A. D., Arnold G. L., Kaufman A. J., Isotopic evidence for an aerobic nitrogen cycle in the latest Archean. Science 323, 1045–1048 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stüeken E. E., A test of the nitrogen-limitation hypothesis for retarded eukaryote radiation: Nitrogen isotopes across a Mesoproterozoic basinal profile. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 120, 121–139 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koehler M. C., Stüeken E. E., Kipp M. A., Buick R., Knoll A. H., Spatial and temporal trends in Precambrian nitrogen cycling: A Mesoproterozoic offshore nitrate minimum. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 198, 315–337 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito M. A., Sigman D. M., Morel F. M. M., The bioinorganic chemistry of the ancient ocean: The co-evolution of cyanobacterial metal requirements and biogeochemical cycles at the Archean–Proterozoic boundary? Inorg. Chim. Acta 356, 308–318 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chester R., Stoner J. H., The distribution of zinc, nickel, manganese, cadmium, copper, and iron in some surface waters from the world ocean. Mar. Chem. 2, 17–32 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klinkhammer G. P., Bender M. L., The distribution of manganese in the Pacific Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 46, 361–384 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landing W. M., Bruland K. W., The contrasting biogeochemistry of iron and manganese in the Pacific Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 51, 29–43 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Canfield D. E., Thamdrup B., Hansen J. W., The anaerobic degradation of organic matter in Danish coastal sediments: Iron reduction, manganese reduction, and sulfate reduction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 3867–3883 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canfield D. E., The early history of atmospheric oxygen: Homage to Robert M. Garrels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 1–36 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haqq-Misra J. D., Domagal-Goldman S. D., Kasting P. J., Kasting J. F., A revised, hazy methane greenhouse for the Archean Earth. Astrobiology 8, 1127–1137 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Derry L. A., Causes and consequences of mid-Proterozoic anoxia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8538–8546 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jimenez-Lopez C., Romanek C. S., Precipitation kinetics and carbon isotope partitioning of inorganic siderite at 25°C and 1 atm. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 557–571 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J., Morse J. W., Influences of alkalinity and pCO2 on CaCO3 nucleation from estimated Cretaceous composition seawater representative of “calcite seas”. Geology 38, 115–118 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruno J., Wersin P., Stumm W., On the influence of carbonate in mineral dissolution: II. The solubility of FeCO3 (s) at 25°C and 1 atm total pressure. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 1149–1155 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halevy I., Alesker M., Schuster E. M., Popovitz-Biro R., Feldman Y., A key role for green rust in the Precambrian oceans and the genesis of iron formations. Nat. Geosci. 10, 135–139 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rasmussen B., Meier D. B., Krapež B., Muhling J. R., Iron silicate microgranules as precursor sediments to 2.5-billion-year-old banded iron formations. Geology 41, 435–438 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasmussen B., Krapež B., Muhling J. R., Suvorova A., Precipitation of iron silicate nanoparticles in early Precambrian oceans marks Earth’s first iron age. Geology 43, 303–306 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Konhauser K. O., Planavsky N. J., Hardisty D. S., Robbins L. J., Warchola T. J., Haugaard R., Lalonde S. V., Partin C. A., Oonk P. B. H., Tsikos H., Lyons T. W., Bekker A., Johnson C. M., Iron formations: A global record of Neoarchaean to Palaeoproterozoic environmental history. Earth Sci. Rev. 172, 140–177 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Canfield D. E., Rosing M. T., Bjerrum C., Early anaerobic metabolisms. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 361, 1819–1834 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Konhauser K. O., Amskold L., Lalonde S. V., Posth N. R., Kappler A., Anbar A., Decoupling photochemical Fe(II) oxidation from shallow-water BIF deposition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 258, 87–100 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Algeo T. J., Luo G. M., Song H. Y., Lyons T. W., Canfield D. E., Reconstruction of secular variation in seawater sulfate concentrations. Biogeosciences 12, 2131–2151 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Habicht K. S., Canfield D. E., Isotope fractionation by sulfate-reducing natural populations and the isotopic composition of sulfide in marine sediments. Geology 29, 555–558 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Habicht K. S., Gade M., Thamdrup B., Berg P., Canfield D. E., Calibration of sulfate levels in the Archean ocean. Science 298, 2372–2374 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jamieson J. W., Wing B. A., Farquhar J., Hannington M. D., Neoarchaean seawater sulphate concentrations from sulphur isotopes in massive sulphide ore. Nat. Geosci. 6, 61–64 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Planavsky N. J., Bekker A., Hofmann A., Owens J. D., Lyons T. W., Sulfur record of rising and falling marine oxygen and sulfate levels during the Lomagundi event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18300–18305 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scott C., Wing B. A., Bekker A., Planavsky N. J., Medvedev P., Bates S. M., Yun M., Lyons T. W., Pyrite multiple-sulfur isotope evidence for rapid expansion and contraction of the early Paleoproterozoic seawater sulfate reservoir. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 389, 95–104 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schröder S., Bekker A., Beukes N. J., Strauss H., Van Niekerk H. S., Rise in seawater sulphate concentration associated with the Paleoproterozoic positive carbon isotope excursion: Evidence from sulphate evaporites in the ~2.2–2.1 Gyr shallow-marine Lucknow Formation, South Africa. Terra Nova 20, 108–117 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luo G., Ono S., Huang J., Algeo T. J., Li C., Zhou L., Robinson A., Lyons T. W., Xie S., Decline in oceanic sulfate levels during the early Mesoproterozoic. Precambrian Res. 258, 36–47 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kah L. C., Lyons T. W., Frank T. D., Low marine sulphate and protracted oxygenation of the Proterozoic biosphere. Nature 431, 834–838 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.W. Stumm, J. J. Morgan, Aquatic Chemistry: An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters (John Wiley, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klinkhammer G., Bender M., Weiss R. F., Hydrothermal manganese in the Galapagos Rift. Nature 269, 319–320 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klinkhammer G., Rona P., Greaves M., Elderfield H., Hydrothermal manganese plumes in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge rift valley. Nature 314, 727–731 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sholkovitz E. R., Flocculation of dissolved organic and inorganic matter during the mixing of river water and seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 40, 831–845 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sholkovitz E. R., The flocculation of dissolved Fe, Mn, Al, Cu, Ni, Co and Cd during estuarine mixing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 41, 77–86 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kump L. R., Seyfried W. E. Jr, Hydrothermal Fe fluxes during the Precambrian: Effect of low oceanic sulfate concentrations and low hydrostatic pressure on the composition of black smokers. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 235, 654–662 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bekker A., Slack J. F., Planavsky N., Krapež B., Hofmann A., Konhauser K. O., Rouxel O. J., Iron formation: The sedimentary product of a complex interplay among mantle, tectonic, oceanic, and biospheric processes. Econ. Geol. 105, 467–508 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 86.D. E. Canfield, Organic matter oxidation in marine sediments, in Interactions of C, N, P and S Biogeochemical Cycles and Global Change, R. Wollast, F. T. Mackenzie, L. Chou, Eds. (Springer, 1993), pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Poulton S. W., Biogeochemistry: Early phosphorus redigested. Nat. Geosci. 10, 75–76 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Feely R. A., Trefry J. H., Lebon G. T., German C. R., The relationship between P/Fe and V/Fe ratios in hydrothermal precipitates and dissolved phosphate in seawater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 2253–2256 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poulton S. W., Canfield D. E., Co-diagenesis of iron and phosphorus in hydrothermal sediments from the southern East Pacific Rise: Implications for the evaluation of paleoseawater phosphate concentrations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5883–5898 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krissansen-Totton J., Buick R., Catling D. C., A statistical analysis of the carbon isotope record from the Archean to Phanerozoic and implications for the rise of oxygen. Am. J. Sci. 315, 275–316 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/11/eaao4795/DC1

Supplementary Text

fig. S1. Estimated annual fluxes of C, N, P, and O2 consumption as a function of depth.

fig. S2. Box model schematic.

fig. S3. P concentrations and organic C/P ratios in marginal marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks.