ABSTRACT

In age-related diseases, rise in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) causes fragmentation of mitochondrial network. Our recent study demonstrated that ROS activation of TRPM2 (transient receptor potential melastatin-2) channels triggers lysosomal Zn2+ release that, in turn, triggers mitochondrial fragmentation. The findings provide new mechanistic insights that may have therapeutic implications.

KEYWORDS: calcium, cell proliferation, cell migration, lysosomal membrane permeabilisation, mitochondrial dynamics, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, TRPM2, zinc

In a normal cell, mitochondria exist as a tubular network that undergoes continuous fission and fusion1. Fission helps to eliminate dysfunctional parts of the network via mitophagy, whilst fusion allows merger of the functionally intact parts with the healthy mitochondrial network. These processes, collectively known as ‘mitochondrial dynamics' ensure maintenance of a healthy network required for efficient energy production and mitochondrial signalling.

The molecular machinery required for mitochondrial dynamics is mostly known.1 Mitochondrial fission is initiated by the ER (endoplasmic reticulum)-mediated constriction of the mitochondrial tubule and recruitment of Drp1 (dynamin-related protein) from the cytoplasm onto the mitochondria via its receptors, mitochondrial fission factor (MFF) and mitochondrial dynamics protein 51 (MID51). Drp-1 molecules form a spiral around the ER-constricted fission site, and together with dynamin 2, cause mitochondrial fission. Mitofusin-1/2 (MFN-1/2) and OPA1 (Optic atrophy type 1) catalyse the fusion of the outer and inner membranes of mitochondria, respectively.

Mitochondrial dynamics is finely regulated, but this regulation goes awry in a wide range of seemingly unrelated human diseases, including cardiovascular (e.g. ischemia), neuronal (Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and stroke) and infectious (some) diseases and certain cancers.1,2 A unifying feature of these diseases, however, is that many of them are age-related and are associated with an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is a powerful stimulant of mitochondrial fission, but how ROS signal mitochondrial fission has remained unclear.

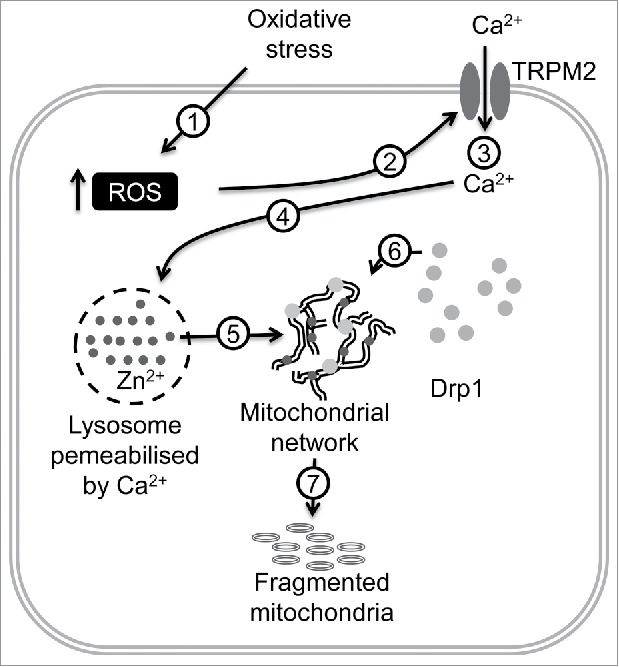

In our recent publication,3 we demonstrated that ROS use the oxidative stress-sensitive TRPM2 channel to signal mitochondrial fragmentation. We used high glucose (diabetic) stress to stimulate ROS production and mitochondrial fragmentation in endothelial cells.4 We found that chemical inhibition, RNAi-silencing and knock-out of TRPM2 channels prevented high glucose-induced mitochondrial fragmentation.3 Given that Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria is Ca2+-dependent, the results presented no surprise. However, as TRPM2 activation can also rise cytosolic Zn2+, we tested the effect of Zn2+ chelators. The result was rather unexpected: Zn2+ chelators completely inhibited high glucose-induced mitochondrial fission. Follow-up studies led to the discovery of a novel signalling pathway involving an intriguing interplay between Ca2+ and Zn2+ in inter-organelle communication that ultimately leads to mitochondrial fission (Fig. 1).3

Figure 1.

Schematic of how diabetic stress induces mitochondrial fragmentation in endothelial cells. High glucose induces ROS (reactive oxygen species) production (1) leading to TRPM2 (transient receptor potential melastatin-2) activation (2), extracellular Ca2+ entry (3), Ca2+-induced lysosomal membrane permeabilisation (4), Zn2+ (dark grey dots) transfer from lysosomes to mitochondria (5), Zn2+-induced Drp1 (dynamin-related protein-1, light grey solid circles) recruitment to mitochondria (6) and finally, mitochondrial fragmentation (7).

The first step in the signalling pathway was a rise in intracellular ROS by the diabetic stress. By stimulating the TRPM2 channel, ROS increased the cytosolic Ca2+. Rise in Ca2+ triggered lysosomal membrane permeabilisation (LMP), leading to the release of its contents, including free Zn2+. Inhibition of TRPM2 channels prevented LMP completely.3 This result is interesting in itself because although it is known that Ca2+ plays a role in ROS-induced LMP, the signalling protein responsible for the Ca2+ rise was hitherto unknown. The finding could dispel the current notion that LMP is a nonspecific process and may have implications for lysosomal diseases.5

We found that the lysosomal Zn2+ release was accompanied an accumulation of free Zn2+ in mitochondria.3 How Zn2+ escapes sequestration by the cytosolic buffers (e.g. metallothioneins) and enters mitochondria is unclear, but presence of lysosomes in the proximity of mitochondria and mitochondrial membrane transport mechanisms might be important. Rise in mitochondrial Zn2+ led to the recruitment of cytoplasmic Drp1 onto mitochondria and the consequent mitochondrial fragmentation. Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria requires depolarisation of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψmt) and is regulated by multiple posttranslational modifications.1 Zn2+ could cause a loss of Δψmt by virtue of its ability to inhibit the mitochondrial electron transport chain.6 However, what effect Zn2+ might have on the posttranslational modifications to promote mitochondrial Drp1 recruitment remains to be established. Regardless of the mechanisms, our study demonstrated that Zn2+ is ultimately responsible for mitochondrial fragmentation.

Excessive mitochondrial fragmentation is generally associated with apoptotic cell death. Previous studies suggested that LMP leads to mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptosis. Proteolytic actions of cathepsins released during LMP are thought to activate the pro-apoptotic bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) pathway to induce intrinsic apoptosis.5 Given our finding that Zn2+ induces mitochondrial fragmentation, and its previously known role in apoptosis,7 it seems reasonable to suggest that Zn2+ might carry the apoptotic signal from lysosomes to mitochondria.

Mitochondrial fission is associated with cancer cell proliferation and migration.1,2 Certain cancer cells display fragmented mitochondria due to increased expression or activation of Drp1, coupled with the downregulation of MFN-2. Importantly, reducing the mitochondrial fragmentation through Drp1 inhibition or MFN2 overexpression has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation.1,2 Notably, growth factor stimulation of K-Ras (Kirsten ras oncogene) increases ERK (Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase)-2-mediated Drp-1 phosphorylation, mitochondrial Drp1 recruitment and fragmentation leading to tumour growth.1 As cancer cells often contain increased levels of ROS, it is reasonable to speculate a role for ROS-activated, TRPM2-mediated Zn2+ signalling in cancer cell proliferation. Supporting this idea, TRPM2 is upregulated in several cancers and its inhibition prevented prostate cancer (PC-3) cell proliferation.8 Mitochondrial fission is also associated with cancer cell migration where fragmented mitochondria move towards the leading edge (lamellipodia) of migrating cells, which again was prevented by Drp1 inhibition.9 Whether TRPM2-mediated Zn2+ signalling plays a role in this process is not known, but we have demonstrated that TRPM2 inhibition as well as Zn2+ chelation inhibits PC-3 and HeLa cell migration.10

In conclusion, the stress signalling pathway identified in our study has provided new fundamental knowledge on how ionic signalling facilitates inter-organelle communication to drive mitochondrial fragmentation. The results have implications for a number of human diseases including cancer, and may have therapeutic potential.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG/10/68/28528) and Ministry of Higher Education, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Chen H, Chan DC. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Regulating the Unique Phenotypes of Cancer and Stem Cells. Cell Metab. 2017;26:39-48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.016. PMID:28648983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archer SL. Mitochondrial dynamics–mitochondrial fission and fusion in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2236-2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1215233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abuarab N, Munsey TS, Jiang LH, Li J, Sivaprasadarao A. High glucose-induced ROS activates TRPM2 to trigger lysosomal membrane permeabilization and Zn2+-mediated mitochondrial fission. Sci Signal. 2017;10(490):1-11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aal4161. PMID:28765513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shenouda SM, Widlansky ME, Chen K, Xu G, Holbrook M, Tabit CE, Hamburg NM, Frame AA, Caiano TL, Kluge MA, et al.. Altered mitochondrial dynamics contributes to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;124:444-453. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014506. PMID:21747057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serrano-Puebla A, Boya P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death: new evidence and implications for health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1371:30-44. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sensi SL, Paoletti P, Bush AI, Sekler I. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:780-791. doi: 10.1038/nrn2734. PMID:19826435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manna PT, Munsey TS, Abuarab N, Li F, Asipu A, Howell G, Sedo A, Yang W, Naylor J, Beech DJ, et al.. TRPM2 mediated intracellular Zn2+ release triggers pancreatic beta cell death. Biochem J. 2015;466:537-546. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140747. PMID:25562606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng X, Sikka SC, Huang L, Sun C, Xu C, Jia D, Abdel-Mageed AB, Pottle JE, Taylor JT, Li M. Novel role for the transient receptor potential channel TRPM2 in prostate cancer cell proliferation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13:195-201. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.55. PMID:20029400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Zhang J, Yu M, Xie Y, Huang Y, Wolff DW, et al.. Mitochondrial dynamics regulates migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:4814-4824. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F, Abuarab N, Sivaprasadarao A. Reciprocal regulation of actin cytoskeleton remodelling and cell migration by Ca2+ and Zn2+: role of TRPM2 channels. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:2016-2029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.179796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]