ABSTRACT

Purpose: Population-based prevalence surveys were undertaken to determine whether trachoma is a public health problem in Laos requiring implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement).

Methods: The country was divided into 19 evaluation units (EUs), each containing a population of roughly 100,000–350,000 people. Of these, 16 were believed most likely to harbor trachoma (based on historical evidence), and were mapped using the Global Trachoma Mapping Project methods. A 2-stage cluster sampling was used to sample approximately 1222 children aged 1–9 years in each EU, as well as all adults aged 15 years and older resident in households with children. The presence or absence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and of trichiasis was documented in each subject, and prevalences (adjusted for age and sex) estimated.

Results: The adjusted prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 0.2% to 2.2% across the 16 EUs. Adjusted all-ages prevalence of trichiasis was 0.00% in 13 EUs, 0.06% in two EUs, and 0.12% in one EU. The trichiasis prevalence in adults in the last EU was 0.19%.

Conclusions: The assessment included all areas of Laos suspected of ever harboring trachoma and most of the rural population of the country. The low prevalence of TF and trichiasis do not warrant any special programs against trachoma at this time.

KEYWORDS: Laos, trachoma, trichiasis

Introduction

Trachoma is an important cause of global blindness. Blindness from trachoma can be prevented using the World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended SAFE strategy (Surgery for trichiasis, Antibiotics to treat Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and Facial cleanliness and environmental improvement to reduce transmission). Using the SAFE strategy, WHO and its partners have committed to the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem by the year 2020.1

WHO guidelines for implementing (and discontinuing) the A, F, and E components of SAFE are based on the population-level prevalence of the clinical sign trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in 1–9-year-old children, while the population-level prevalence of the sign trachomatous trichiasis (TT) informs the local requirements for surgical services. A country is considered to have a public health problem with trachoma if one or more evaluation units (EUs) in the country have a prevalence of TF ≥5% in 1–9-year-olds or if the TT prevalence unknown to the health system in the all-ages population is ≥0.1%.

In 2012, the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) was initiated;2 it uses WHO survey guidelines1 and includes rigorous training of survey teams, use of electronic data capture techniques, and standardized processes for data cleaning, analysis and reporting.3

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) is surrounded by China, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand. It is divided into 17 provinces including one comprising the national capital, Vientiane, and its surrounds. In the most recent census (2005), the estimated total national population was 6.2 million with the overall population density estimated to be 26.9 people/km2.4

Before this survey, only one study relating to trachoma in Laos had been published in an international peer-reviewed journal.5 In 1972, Beauchamp and colleagues conducted a study among 1097 school children on the outskirts of Vientiane city, and found MacCallan stage I or II trachoma in 552/957 students aged 15–20 years.5,6

In 2000, a trachoma rapid assessment (TRA) was conducted in five provinces (Oudamxay, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Salavan, and Sekong), finding overall, 0.03% of adults examined had trichiasis, and 14.8% of children examined had TF and/or trachomatous inflammation – intense (TI) (personal communication, Khamphoua Southisobath). The highest TF percentages were in Baeng (Oudamxay), Xieng and Ngeun (Luang Prabang), Feung and Xai (Vientiane), Vapi and Laongan (Salavan), and Lamam and Thataey (Sekong). No specific trachoma control activities were implemented.

Discussions with provincial hospitals in 2011 revealed that no trichiasis surgery had been performed in eight provinces that year, while a total of 48 surgeries had been carried out in the other 10 provinces.

Thus it is clear that trachoma has existed in Lao PDR in the past and that there are still some people with trichiasis; however, from this data it is not possible to ascertain the magnitude of the current problem.

The current study was undertaken using the GTMP methodology to determine the need for interventions against trachoma in Lao PDR.

Materials and methods

The GTMP methods were used, which follow the WHO recommendations1 in proposing that the survey area be divided into EUs containing roughly 100,000-250,000 residents. Two provinces, Champasack and Savannakhet, had populations over 500,000 people and were split into two EUs each. In Vientiane Prefecture, five peri-urban districts were included and counted as one EU. Thus, 19 EUs were defined, which comprised the entire country. These are listed in Table 1 along with their areas and population size. Three EUs were not surveyed because they were predominantly urban areas where there was no history of trachoma and none was expected to be found.

Table 1.

Evaluation units (EUs) for the National Trachoma Assessment, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2013–2014.

| EU | Province | Surface area, km2 | Population, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attapeu | 10,320 | 123,816 |

| 2 | Bokeo | 6196 | 158,696 |

| 3 | Bolikhamsai | 14,863 | 247,556 |

| 4a | Champasak A (Pakse, Phonethong, Soukhouma, Mounlapamok, & Khong districts) | 15,415 | 337,129 |

| 5 | Champasak B (Xanasomboun, Bachieng, Pakxong, Pathoumphone, & Champasak districts) | 293,739 | |

| 6 | Hua Phan | 16,500 | 288,287 |

| 7 | Khammouane | 16,315 | 353,535 |

| 8 | Luang Namtha | 9325 | 281,439 |

| 9 | Luang Prabang | 16,875 | 413,165 |

| 10 | Oudomxay | 15,370 | 281,439 |

| 11 | Phongsali | 16,270 | 166,635 |

| 12 | Sayabouly | 16,389 | 360,187 |

| 13 | Salavan | 10,691 | 358,761 |

| 14a | Savannakhet A (Artsaphangthong, Phin, Sepone, Nong, Tharpangthong, Xonbouly, Vilabouly, Artsaphone & Phalanxay districts) | 21,774 | 503,063 |

| 15 | Savannakhet B (Kaisone, Outhoumphone, Songkhone, Champhone, Xaybouly & Xayphouthong districts) | 369,096 | |

| 16 | Sekong | 7665 | 98,481 |

| 17a | Vientiane Prefecture (Naxaythong, Xaythany, Hadxayfong, Santhong & Pakngeum districts) | 392,234 | |

| 18 | Vientiane Province | 15,927 | 453,983 |

| 19 | Xieng Khouang | 15,880 | 258,742 |

aThese EUs are mostly urban and were not surveyed.

Sample size was calculated based only on parameters relating to TF; the low prevalence of trichiasis (nearly always <0.2% in adults ≥15 years except in the most hyperendemic areas) means that accurately estimating its prevalence requires prohibitively large samples, and the loss of precision in the estimate of TT prevalence inherent in this approach is generally accepted.

To have 95% confidence (α = 5%) of estimating a true TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds of 10% with an absolute precision of 3%, assuming a cluster survey design effect of 2.65 and a non-response rate of 20%, 1222 children would be required.3 A total of 20 clusters (villages) were to be included in each EU, from which a mean of around 61 children would need to be sampled from each cluster. A convenience sample (including all adults age 15+ years in sampled households) was used for estimates of trichiasis.

A 2-stage cluster sampling was used; in the first stage, a probability-proportional-to-size sample of 20 villages was selected for each EU. The second stage of sampling took place in the village. Lao villages are organized into units, each comprising 10–20 households; village leaders have lists of the households and the number of children in each household. Units were selected by random draw until 36 households with children were included; this number was expected to yield around 61 children in each cluster. Examinations were done at the house. All adults aged 15+ years in selected households with children aged 1–9 years were examined for trichiasis.

Informed verbal consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of children aged 1–9 years for examination for TF and TI. The WHO simplified trachoma grading scheme was used, with binocular magnifying loupes and sunlight or a torch for illumination. Consenting individuals over 15 years of age present in the household were examined with torch and loupes for trichiasis. The standard GTMP examination protocol was used with one GTMP-certified grader, one GTMP-certified recorder, and a local guide from the health center. GPS data were collected at each participating household.

All individuals with TF and/or TI were provided with antibiotic treatment and cases of trichiasis were provided with a referral.

Teams were trained following the standard GTMP training.3,7 In order to ensure that there would be enough children with TF for adequate training and certification, grader candidates travelled in October 2013 to Bishoftu, Ethiopia to undergo the GTMP grader training and certification. A kappa score ≥0.70 for the diagnosis of TF, obtained in a live-subject inter-grader agreement test with a GTMP-certified grader trainer providing the gold standard diagnoses, was required for grader certification.3 Graders who qualified then joined the recorders in Laos for additional team training in the survey methodology and field procedures.

All data, including consent, were captured electronically, using the purpose-built Open Data Kit-based Android phone application developed by the GTMP.3 The data tool was in English. Once saved and verified by a national official, data were sent and stored in the dedicated cloud-based, high security GTMP server. The data were cleaned and analyzed to estimate the age-adjusted prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds, and the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in adults for each EU3. Confidence intervals were calculated by bootstrap, with 10,000 replicates. The age- and sex- adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in the whole population was estimated by multiplying the estimated prevalence in adults by the proportion of the population thought to be aged 15 years and older (0.606)4; this assumes that there was no trichiasis in children, a valid assumption in nearly all populations. Approval for the study was provided by the local Laos Ministry of Health, through the lead author, and the study adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

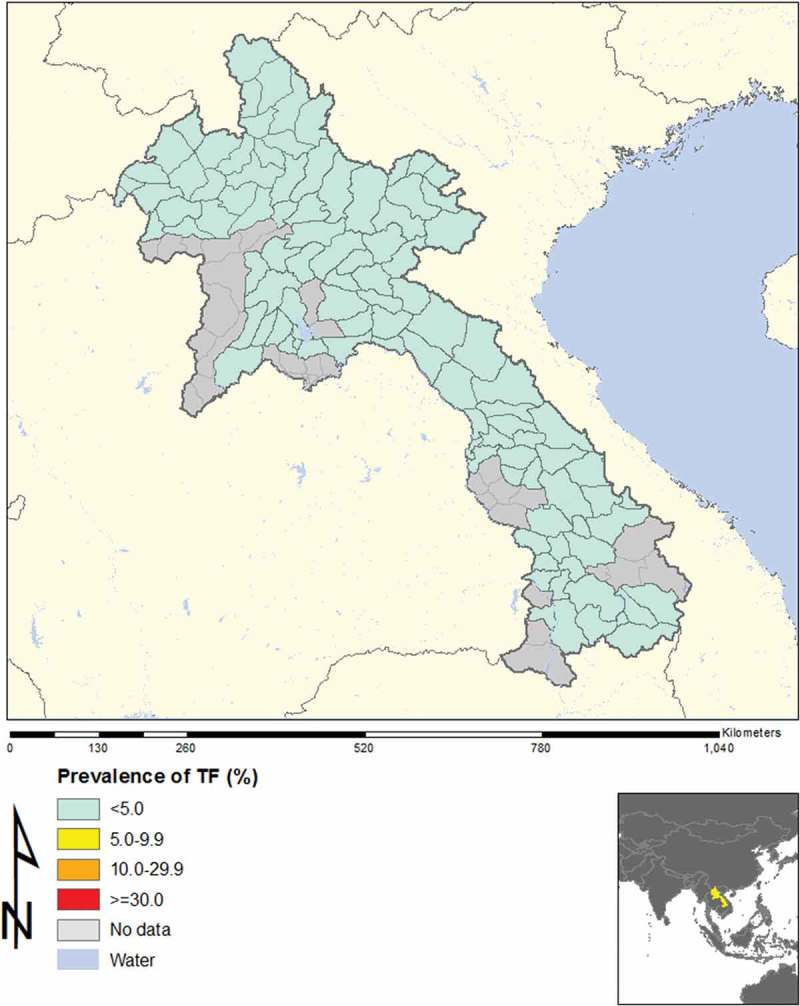

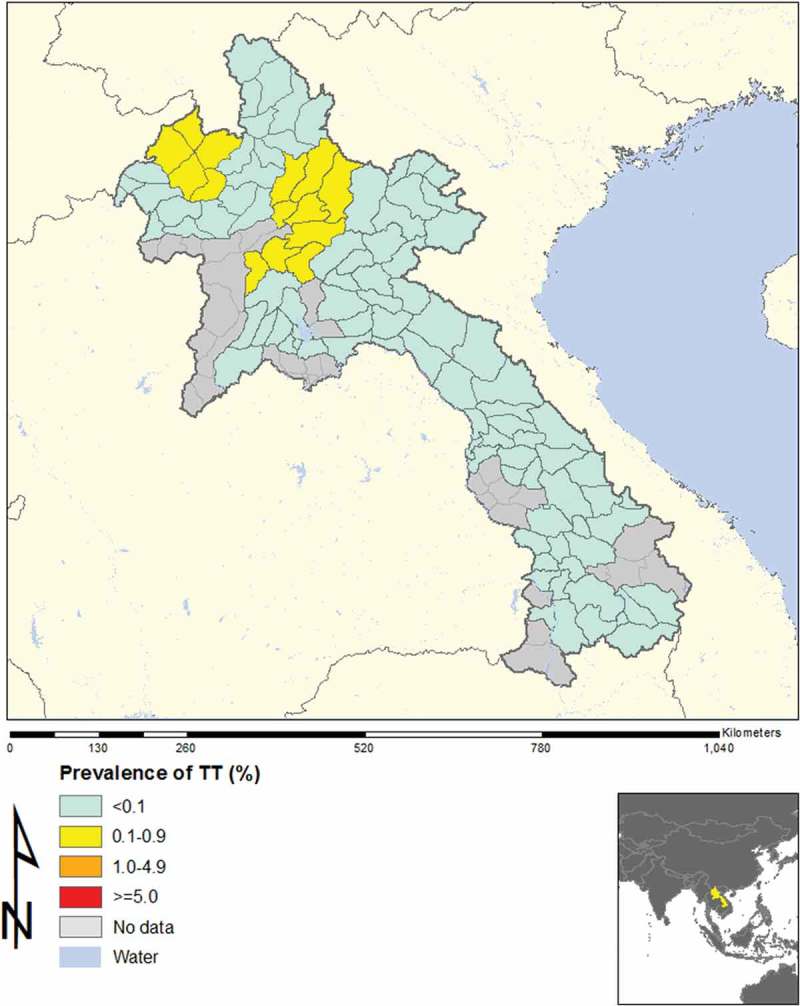

In total, across 16 EUs, from November 2013 to August 2014, our field teams examined 21,566 children aged 1–9 years, and 15,052 adults aged ≥15 years. The TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds was <5% in every EU, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Regarding trichiasis, in one EU (Luang Namtha) the prevalence in the total population was 0.12%, which is just over the elimination threshold of 0.1%;8 the trichiasis prevalence in adults was 0.19%, which is just under the 0.2% elimination threshold expressed for adults. This was due to only two cases of trichiasis, which were identified in two different clusters. The ages of the two people were 50 and 65 years, and each had unilateral trichiasis (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and trichiasis in 16 evaluation units, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2013–2014.

| Evaluation unit | Children examined, n | TF cases found, n | Age-adjusted TF prevalence 1–9-year olds, % (95% CI) | Adults examined, n | Adults with trichiasis, n | Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in adults 15+ years, % (95% CI) | Age-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in whole population, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attapeu | 1382 | 28 | 1.5 (0.4–2.7) | 1035 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bokeo | 1394 | 6 | 0.4 (0.0–0.8) | 1067 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bolikhamsai | 1214 | 10 | 0.8 (0.0–1.8) | 774 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Champasak B | 1293 | 3 | 0.2 (0.0–0.5) | 741 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Huaphan | 1392 | 22 | 1.5 (0.4–3.1) | 964 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Khammouan | 1248 | 2 | 0.2 (0.0–0.4) | 803 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Luang Namtha | 1339 | 9 | 0.5 (0.1–1.0) | 906 | 2 | 0.19 (0.00–0.52) | 0.12 |

| Luang Prabang | 1175 | 2 | 0.2 (0.0–0.6) | 1150 | 4 | 0.12 (0.00–0.33) | 0.06 |

| Oudomxay | 1494 | 24 | 1.3 (0.3–2.1) | 1083 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Phongsaly | 1277 | 31 | 2.2 (1.1–3.6) | 1028 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Salavan | 1463 | 12 | 0.7 (0.0–1.8) | 1010 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Savanakhet B | 1430 | 4 | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 814 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Vientiane | 1241 | 11 | 0.6 (0.0–1.5) | 852 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Xiengkouang | 1238 | 18 | 1.2 (0.6–1.9) | 922 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sayabouly | 1224 | 5 | 0.4 (0.0–0.8) | 952 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sekong | 1762 | 26 | 1.4 (0.6–2.3) | 951 | 1 | 0.05 (0.00–0.16) | 0.03 |

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2013–2014.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of trachomatous trichiasis (TT), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2013–2014.

In three EUs there was one cluster in each in which the proportion of children who had TF was slightly above 10%; additional investigations were undertaken to assess if these might be potential “hot spots.” The full details of the laboratory investigation will be reported elsewhere, but examination of all children (n = 951) in nine communities (comprising the three communities in which the index clusters were located, plus two further communities located close to each of those communities, with similar ethnic, socio-cultural, economic, and environmental characteristics) found only 14 TF cases; none of the nine communities had a TF prevalence above 5%.

Discussion

The National Trachoma Assessment in Lao PDR included all of the country except for urban areas. The 16 EUs (roughly equivalent to provinces) included all areas where trachoma had been reported in the past. In every EU, the prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds was found to be <5%. Concerns about potential hot spots in or around three clusters were addressed by additional investigations; none of these areas yielded findings that would suggest that active trachoma was a public health problem. Thus, the prevalence of TF in Laos is clearly below the WHO threshold for elimination as a public problem.

No cases of trichiasis were found in 13 of the EUs, and among the other three EUs, the estimated (age- and sex-adjusted) trichiasis prevalences in the all-ages population were 0.03%, 0.06% and 0.12%. The last EU (Luang Namtha) had only two cases of trichiasis identified, both of which were unilateral. Unfortunately, the threshold of 0.1% is so low that, for a rare condition such as trichiasis, the presence or absence of one or two cases can determine whether an EU “passes” or “fails” the elimination benchmark. Further, among trichiasis cases, the lack of inclusion of grading of trachomatous conjunctival scarring at the time of the survey makes it impossible to determine whether the trichiasis was due to trachoma. There is a growing realization of the potential importance of other etiologies of trichiasis, and the potential circularity of defining “trachomatous trichiasis” as trichiasis found in a trachoma-endemic population.9,10 Considering that no trichiasis surgery was reported from the eye unit in Luang Namtha in 2011, a specific program for trichiasis surgery does not appear to be warranted. It is possible that the sampling excluded elderly people with trichiasis who might have been living in households without children, however, given the usual custom of rural elderly living in households with their children and grandchildren, this seems unlikely.

A further consideration for the trichiasis prevalence estimate for Luang Namtha is that, since we originally analyzed these data, the WHO position on the trichiasis prevalence target has been clarified11 to conform with the reasoning of the second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma,12 held in 2003. At that meeting, the elimination prevalence threshold was established as 0.2% in adults, which was felt at the meeting to be more easily expressed as 1 case per 1000 total population (using the assumption that 50% of the population was aged 15 years or older). In practice, most programs estimate trichiasis prevalence in adults, and the assumption that ≥15-year-olds comprise half of the total population is rarely exactly true. WHO now advise that the elimination threshold for trichiasis can be expressed using either adults (prevalence <0.2%) or the all-ages population (<0.1%) as the denominator;11 using the former definition, all EUs in Laos had trichiasis prevalences below the elimination target.

Our work has a number of potential limitations. First, our surveys were not specifically powered to estimate the prevalence of trichiasis.3 We have, however, provided confidence intervals, and can leave the reader to judge the repeatability of the estimates we obtained. Second, our graders had limited previous experience in diagnosing trachoma; for that reason, we undertook intensive training of each participating grader in Ethiopia, and ensured (as elsewhere in the GTMP) that each grader contributing to surveys passed a rigorous test of diagnostic reliability. Third, some of our EUs had population sizes greater than the 100,000–250,000 people recommended by WHO.1 The lack of trachoma found, however, leads us to believe that our conclusions would have been the same had the EUs been framed to fit smaller populations. Taken together, the findings of these surveys suggest that trachoma is not a public health problem in the Lao PDR.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Trainers for Laos team (Bishoftu, Ethiopia, 2013): Yilikal Adamu, Michael Dejene, Tesfaye Haileselassie; Pan-Project: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.

Funding Statement

The fieldwork described in this paper was generously supported by the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) via its END in Asia project, implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project, which provided logistical, epidemiological and data management support, was funded by a grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID)(ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially supported by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, project implementation, data analysis or data interpretation, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript. The contents are the responsibility of the Ministry of Health, Cambodia and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, DFID or the governments of the United States or the United Kingdom.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

The fieldwork described in this paper was generously supported by the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) via its END in Asia project, implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project, which provided logistical, epidemiological and data management support, was funded by a grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID)(ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially supported by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, project implementation, data analysis or data interpretation, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript. The contents are the responsibility of the Ministry of Health, Cambodia and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, DFID or the governments of the United States or the United Kingdom.

References

- 1. Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Solomon AW, The Global Kurlyo E.. Trachoma Mapping Project. Comm Eye Health 2014;27(85):18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solomon AW, Pavluck AL, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steering Committee for Census of Population and Housing. Results from the Lao People’s Democratic Republic Population and Housing Census 2005 Vientiane: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beauchamp FJ, Epardeau B, Siramongkhon P, et al. Le trachome: son endemicite au Laos. Medecine Tropicale 1972;32:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacCallan AF. The epidemiology of trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1931;15:369–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global trachoma mapping project: training for mapping of trachoma (version 3); 2015. [Available at: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/resources/global-trachoma-mapping-project-training-mapping-trachoma]. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control.

- 8. World Health Organization Report of the 3rd global scientific meeting on trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khandekar R, Kidiyur S, Al-Raisi A.. Distichiasis and dysplastic eyelashes in trachomatous trichiasis cases in Oman: a case series. East Mediterr Health J 2004;10:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization Strategic and Technical Advisory Group on Neglected Tropical Diseases. Technical consultation on trachoma surveillance, September 11−12 , 2014, Task Force for Global Health, Decatur, GA, USA (WHO/HTM/NTD/2015.02). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization Validation of elimination of trachoma as a public health problem (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Organization World Health. Report of the 2nd global scientific meeting on trachoma, Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003. (WHO/PBD/GET 03.1). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]