ABSTRACT

Purpose: We aimed to estimate the prevalence of trachoma in each district (“woreda”) of Tigray Region, Ethiopia.

Methods: We conducted 11 cross-sectional community-based surveys in evaluation units covering 34 rural woredas from January to March 2013 using the standardized methodology developed for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project.

Results: Teams visited 8034 households in 275 villages. A total of 28,581 consenting individuals were examined, 16,163 (56.7%) of whom were female. The region-wide adjusted trichiasis prevalence was 1.7% in those aged 15 years and older. All evaluation units mapped had a trichiasis prevalence over the World Health Organization elimination threshold of 0.2% in people aged 15 years and older. The region-wide adjusted prevalence of the clinical sign trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years was 26.1%. A total 10 evaluation units, covering 31 woredas, with a combined rural population of 4.3 million inhabitants, had a prevalence of TF ≥10%, and require full implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement) for at least 3 years before impact surveys are undertaken. Of these, four evaluation units, covering 12 woredas, with a combined rural population of 1.7 million inhabitants, had a TF prevalence ≥30%.

Conclusion: Both active trachoma and trichiasis are public health problems in Tigray, which needs urgent implementation of the full SAFE strategy.

KEYWORDS: Global Trachoma Mapping Project, North Ethiopia, prevalence, trachoma

Introduction

Trachoma is a chronic infectious keratoconjunctivitis that is a major cause of blindness in many developing countries. It presents initially as a follicular conjunctivitis, sometimes with superficial keratitis and corneal vascularization, and gradually progresses (in some people, with repeated ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection) to conjunctival scarring and lid distortion. Damage to the cornea occurs from the chronic inflammatory disease and later (and more importantly) from exposure and trauma from distorted lids and in-turned lashes. Endemic trachoma is a major cause of blindness in poorer rural communities of developing countries, especially in arid areas.1,2

Ethiopia is one of the world’s most trachoma-endemic countries, with trachoma a major preventable cause of blindness nationwide. Tigray is the northern-most region in Ethiopia, and has an estimated population of 4,316,988, of which 80.5% live in rural areas.3 A national survey carried out in 2005–2006 found an estimated national prevalence of active trachoma (trachomatous inflammation – follicular, TF, and/or trachomatous inflammation – intense, TI) of 40.1% in children aged 1–9 years, with an estimated TF prevalence of 25.6% in children in Tigray.4,5

The World Health Organization (WHO) and partners have targeted trachoma for elimination as a public health problem by 2020, by implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery for in-turned eyelashes, antibiotics to clear infection, and facial cleanliness and environmental improvement to reduce infection transmission).6,7 Knowing the baseline prevalences of TF and trichiasis is crucial for control programs, to help guide planning on where and for how long SAFE interventions are required.

We carried out cross-sectional population-based prevalence surveys to estimate the prevalence of TF among children aged 1–9 years, and the prevalence of trichiasis among adults aged 15 years and older, in 11 evaluation units (EUs) covering 34 districts (woredas) throughout Tigray Region.3

Materials and methods

Survey methodology

Tigray Region is divided into seven zones (Central, Eastern, South Eastern, South, West, Northwest and Mekele). All rural zones were included in the survey. Urban areas, including Mekele Special Zone and all woreda towns, were not surveyed. Surveys were undertaken using the standardized Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) sampling methodology.8 The WHO definition of a “district” for the purposes of trachoma prevalence estimates is an administrative area with a population of 100,000–250,000 people. In Tigray, trachoma was expected to be highly endemic, and so larger populations were included in each survey by grouping woredas into EUs of populations up to 500,000 people, so that interventions can be provided in a timely manner, where needed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2013.

We used a 2-stage, cluster random sampling methodology, with clusters (kebeles) selected using a probability proportional to size sampling technique. The kebele was the primary sampling unit, with each kebele regarded as a cluster. Using the latest available census data,3 it was estimated that if teams could survey 30 households per day, then the required sample size of children aged 1–9 years would be reached if 26 kebeles were surveyed for each EU. The list of all kebeles in each EU was obtained from the regional government. Kebeles were excluded if they were considered insecure or not accessible within 90 minutes’ walk from the furthest point that could be reached in a 4-wheel drive vehicle. A developmental team (DT) is the smallest administrative unit in each zone, and served as our secondary sampling unit, with each DT comprising approximately 25–30 households. On the day of the survey, at the kebele, a DT was randomly selected by drawing lots. All households in the selected DT were included in the survey, with all household members at least 1 year of age eligible for inclusion.

Informed verbal consent was obtained before assessment. Clinical assessments were carried out using the WHO simplified trachoma grading system5 and a 2.5× loupe under direct sunlight or torchlight, with the results called to the recorder. Alcohol hand-gel was used between individuals to minimize carry-over contamination.

Data collection

Data were collected using a bespoke Android smartphone application.8 Both recorders and trachoma graders were required to attend the 5-day (version 1) GTMP training course, and pass an exit exam. Full details of the training and examination process are outlined elsewhere.8 Nine teams, each made up of a trachoma grader, a data recorder, and a driver, were used. A supervisor (ST) was in charge of overseeing the work of graders and recorders and assisting them technically, as well as coordinating and leading the overall survey.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Tigray Regional Health Bureau Ethics Committee (2136/7767/05). The overall GTMP survey methodology was approved by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (6319). Informed verbal consent was obtained from all adult individuals who participated in the survey. For children aged <15 years, parents or adult guardians provided consent. All participants found to have active trachoma were provided with 1% tetracycline eye ointment for 6 weeks and those with trichiasis were referred (using a standard referral form) to a nearby health facility for consideration of corrective surgery.

Data analysis

All data analysis was carried out in R 3.0.2 (2013, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), using the GTMP analysis approaches described elsewhere.8 Sample outcomes proportions were adjusted at cluster level to estimates population-level prevalences, with the overall EU prevalence the mean of all adjusted cluster-level proportions in a given EU. TF prevalence estimates were adjusted in 1-year age bands, and trichiasis estimates were adjusted for sex and age in 5-year age bands, using the 2007 Tigray census data.3 Confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed by bootstrapping the adjusted cluster-level outcomes proportions, and taking the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles from the list of 10,000 bootstrap iterates.

Results

Surveys were carried out from January 28 to March 30, 2013. A total of 32,815 people were enumerated from 11 EUs covering 34 woredas, with 8034 households visited in 275 kebeles. Overall, 28,581 people (87.1%) consented to examination and 16,163 (56.7%) of those examined were female. Overall, 10,296 children aged 1–9 years were enumerated, with 10,023 (97.4%) examined. There was a mean of 1.25 children aged 1-9 years per household.

Adjusted TF prevalences ranged from 9.3% (95% CI 6.0–11.3%) in the EU covering Kafta Humera, Welkait and Tsegede woredas, to 41.4% (95% CI 33.8–51.2%) in the EU covering Wefla and Alamata woredas (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2013.

| Evaluation unit | Examined, n | TF cases, n | Unadjusted TF, % | Adjusteda TF, % (95% CIb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laelay Maychew, Naeder Adet, Tahtay Maychew | 766 | 266 | 34.7 | 32.6 (27.0–38.9) |

| Adwa, Mereb Leke, Entecho | 792 | 212 | 26.8 | 23.7 (16.6–29.7) |

| Kolla Tembiyen, Werei Leke, Tanqua Abergele | 857 | 249 | 29.1 | 29.5 (22.3–34.6) |

| Degua Temben, Saharti Samre, Hintalo Wejirat, Enderta | 936 | 419 | 44.7 | 39.1 (30.0–47.3) |

| Erob, Ganta Afeshum, Glomekada, Saesie Tsaedaemba | 762 | 163 | 21.4 | 22.5 (14.4–28.5) |

| Hawzen, Wukero, Atsbi Wenberta | 973 | 185 | 19.0 | 20.0 (15.8–23.3) |

| Wefla, Alamata | 942 | 408 | 43.3 | 41.4 (33.8–51.2) |

| Alaje, Endamehoni, Raya Azebo | 930 | 373 | 40.1 | 41.0 (32.1–50.0) |

| Kafta Humera, Welkait, Tsegede | 1013 | 100 | 9.9 | 9.3 (6.0–11.3) |

| Asgede Tsimbila, Medebay Zana, Tahtay Koraro, Tselemti | 1007 | 185 | 18.4 | 18.3 (13.1–23.9) |

| Laelay Adiyabo, Tahtay Adiyabo | 1045 | 113 | 10.8 | 10.2 (6.3–14.6) |

aAdjusted for age in 1-year age bands using the 2007 Ethiopian national census data for Tigray Region.

b95% CIs from the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of bootstrapped adjusted cluster-level proportions, to account for the clustered sampling design.

CI, confidence interval.

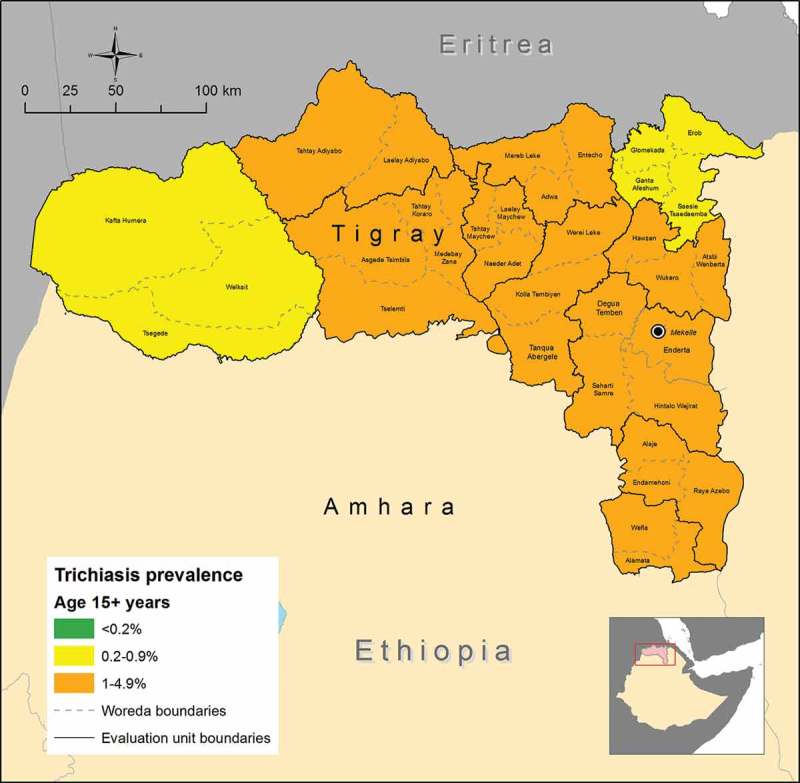

Adjusted trichiasis prevalences in those aged 15 years and older ranged from 0.6% (95% CI 0.1–1.1%) in the EU covering Kafta Humera, Welkait and Tsegede woredas, to 2.6% (95% CI 1.8–3.1%) in the EU covering Degua Temben, Saharti Samre, Hintalo Wejirat and Enderta woredas (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of trichiasis in those aged 15 years and older by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2013.

| Evaluation unit | Examined, n | Trichiasis cases, n | Unadjusted trichiasis, % | Adjusteda trichiasis, % (95% CIb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laelay Maychew, Naeder Adet, Tahtay Maychew | 1237 | 50 | 4.0 | 1.9 (1.1–2.8) |

| Adwa, Mereb Leke, Entecho | 1217 | 46 | 3.8 | 2.3 (1.6–3.0) |

| Kolla Tembiyen, Werei Leke, Tanqua Abergele | 1208 | 29 | 2.4 | 1.4 (0.8–1.8) |

| Degua Temben, Saharti Samre, Hintalo Wejirat, Enderta | 1435 | 66 | 4.6 | 2.6 (1.8–3.3) |

| Erob, Ganta Afeshum, Glomekada, Saesie Tsaedaemba | 1055 | 25 | 2.4 | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) |

| Hawzen, Wukero, Atsbi Wenberta | 1366 | 46 | 3.4 | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) |

| Wefla, Alamata | 1574 | 61 | 3.9 | 2.3 (1.2–3.0) |

| Alaje, Endamehoni, Raya Azebo | 1595 | 48 | 3.0 | 1.9 (1.5–3.0) |

| Kafta Humera, Welkait, Tsegede | 1267 | 14 | 1.1 | 0.6 (0.1–1.1) |

| Asgede Tsimbila, Medebay Zana, Tahtay Koraro, Tselemti | 1550 | 36 | 2.3 | 1.3 (0.8–1.9) |

| Laelay Adiyabo, Tahtay Adiyabo | 1511 | 35 | 2.3 | 1.3 (0.7–1.8) |

aAdjusted for sex and age in 5-year age bands using the 2007 Ethiopian national census data for Tigray Region.

b95% CIs from the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of bootstrapped adjusted cluster-level proportions, to account for the clustered sampling design.

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in those 15 years and older by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Tigray Region, Ethiopia, 2013.

Discussion

Trachoma is highly endemic in Tigray Region. Overall, 19 woredas require mass drug administration (MDA) with azithromycin for 3 years before re-survey, and 12 woredas require MDA for at least 5 years before re-survey, in addition to the F and E components of the SAFE strategy. One EU covering three woredas in Western Tigray Zone (Kafta Humera, Welkait and Tsegede) had a TF prevalence in the range 5.0–9.9%. At this prevalence, the WHO recommends a single round of azithromycin MDA, plus implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy, before re-survey.

We excluded kebeles that were more than 90 minutes walk from the furthest point that could be reached in a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Given that we anticipate trachoma to be mostly found in rural, isolated, populations, it is probable that some cluster of disease was missed by this approach. In our case a balance was sought between making sampled kebeles as representative of the rural population as possible, and the practical considerations that come into any survey carried out in extreme geographical environments. In order to ensure a complete geographical covering in implementing future MDAs, kebeles cannot be excluded by this criteria, and it is possible that with decreasing trachoma prevalence, more isolated areas will have to be included in future mapping.

Every EU surveyed had trichiasis prevalence estimates far higher than the WHO trachomatous trichiasis elimination threshold of 0.2% of the population aged 15 years and older. There is an urgent need for large-scale assessment of rural individuals to case-find the sizeable number of trichiasis cases who need corrective surgery throughout Tigray. This will require significant funding to train and deploy case finders and trichiasis surgeons.

At the time of this survey, WHO had not yet recommended that cases of trichiasis be checked for the presence of trachomatous conjunctival scarring5 to confirm the cause of eyelash deviation to be trachoma, and so the presence or absence of scarring was not assessed by graders here. As not all cases of trichiasis are necessarily trachomatous in origin, it is likely that our trichiasis prevalence estimates will overestimate the true proportion of trachomatous trichiasis cases in the population. However, this figure does not consider the number of cases which will progress from trachomatous scarring to potentially blinding trachomatous trichiasis9 in the time taken to train and deploy surgeons to carry out the current backlog of surgeries. For this reason, the securing of funding and program planning should begin as a matter of urgency. The magnitude of this task should not be underestimated, and much effort will be needed to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem from Tigray Region between now and the 2020 elimination target.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Smith JL, Flueckiger RM, Hooper PJ, et al. The geographical distribution and burden of trachoma in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burton MJ, Mabey DCW.. The global burden of trachoma: a review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009;3(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Population and Housing Census – Tigray Region , 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. Prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2008;21:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey R, Lietman T.. The SAFE strategy for the elimination of trachoma by 2020: will it work? Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:233–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emerson PM, Burton M, Solomon AW, et al. The SAFE strategy for trachoma control: using operational research for policy, planning and implementation. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:613–619. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2627433&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed September2, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muñoz B, Bobo L, Mkocha H, et al. Incidence of trichiasis in a cohort of women with and without scarring. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:1167–1171. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10661664. Accessed January1, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]