ABSTRACT

Purpose: Trachoma is a major cause of blindness in Ethiopia, and targeted for elimination as a public health problem by the year 2020. Prevalence data are needed to plan interventions. We set out to estimate the prevalence of trachoma in each evaluation unit of grouped districts (“woredas”) in Benishangul Gumuz region, Ethiopia.

Methods: We conducted seven cross-sectional community-based surveys, covering 20 woredas, between December 2013 and January 2014, as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP). The standardized GTMP training package and methodologies were used.

Results: A total of 5828 households and 21,919 individuals were enumerated in the surveys. 19,583 people (89.3%) were present when survey teams visited. A total of 19,530 (99.7%) consented to examination, 11,063 (56.6%) of whom were female. The region-wide age- and sex-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in adults aged ≥15 years was 1.3%. Two evaluation units covering four woredas (Pawe, Mandura, Bulen and Dibate) with a combined rural population of 166,959 require implementation of the A, F and E components of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvement) for at least three years before re-survey, and intervention planning should begin for these woredas as soon as possible.

Conclusion: Both active trachoma and trichiasis are public health problems in Benishangul Gumuz, which needs implementation of the full SAFE strategy.

KEYWORDS: Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, prevalence, trachoma, trichiasis

Introduction

Trachoma is an eye disease caused by infection with the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. It is the primary infectious cause of blindness in the world.1 Active trachoma presents as a chronic kerato-conjunctivitis, manifesting principally as follicular inflammation with or without pronounced conjunctival edema and thickening. This resolves with conjunctival scarring, which in some people, after many such episodes, leads to entropion, trichiasis and ultimately blinding corneal opacification.2 Infection is transmitted from eye to eye by hands, clothing and other fomites, and eye-seeking flies.2,3

Globally, the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) estimates suggest that 200 million people live in endemic communities and are at risk of blindness due to trachoma,4 with Ethiopia thought to be the world’s most trachoma-affected country.

Trachoma-endemic communities are usually in dry and dusty areas, mired in poverty, and have poor sanitation.5–8 A number of household risk factors have also been associated with increased disease prevalence, including limited water availability, absence of latrines, and presence of flies.9–12 Active trachoma (trachomatous inflammation – follicular, TF, and/or trachomatous inflammation – intense) is mostly seen in young children, with peak prevalence at around 4–6 years of age, while subsequent scarring and blindness are seen in adults.13

The Ethiopian National Survey of Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma, carried out in 2005–2006, reported that trachoma was the second major cause of blindness nation-wide,14 and estimated that over 9 million children were affected by active trachoma nationally.14 At that time, the estimated prevalence of TF in children in Benishangul Gumuz region as a whole was 0.9%, while the estimated prevalence of trachomatous trichiasis in adults was 0.1%.14 However, prior to 2013 no finer-resolution trachoma surveys had been conducted in the region.

Objectives

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of trachoma in evaluation units (EUs) of grouped districts (woredas) in Benishangul Gumuz region. Specific objectives were to estimate the prevalence of the clinical sign TF in children aged 1–9 years in each EU and to estimate the prevalence of trichiasis in those aged 15 years and older in each EU, to inform future trichiasis surgery requirements.

Materials and methods

Study area

Benishangul Gumuz is a region with a land area of approximately 51,000km2, located in the north-west of Ethiopia. It shares borders with the State of Amhara in the east, Sudan in the north-east, and the State of Oromia in the south. It is administratively divided into zones, woredas and kebeles (the smallest administrative units for which population estimates are available). The region has an estimated 656,000 inhabitants, 90% of whom live in rural areas.15

Study design

Seven cross-sectional community-based surveys were conducted between December 2013 and January 2014, as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP). The standardized GTMP training package (version 1) and methodologies were used.16

Sample size

Each survey was designed to estimate an expected 10% TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds with an absolute precision of 3%. We therefore needed to sample, in each EU, sufficient households such that 1222 children aged 1–9 years would be resident therein. We planned each cluster to include 30 households, as this was the number that we expected a team could cover in 1 day. Full details of the sample size calculation are outlined elsewhere.16 From the latest available census data15 we estimated that a 30-household cluster in Benishangul Gumuz would include a mean of 44 children aged 1–9 years. Therefore, 28 clusters of 30 households were sampled for each EU.

Cluster and household selection

The administrative structure in Benishangul Gumuz includes three zones, 20 woredas, and 474 kebeles. Respecting existing administrative boundaries, seven EUs were constructed by grouping woredas together, based on common borders, similar socioeconomic characteristics, and an aim to estimate trachoma prevalence in population units of 100,000–250,000 people16 (Figure 1). Selection of kebeles (clusters) was carried out by an in-country GTMP public health consultant (MD) and the list of selected clusters was given to the survey coordinators from the regional health bureau. Kebeles were selected using a probability proportional to size sampling methodology. On the day of the survey, one subdivision of the kebele (a “got”) was selected randomly, by drawing lots. All households in the selected got were eligible for inclusion. All kebeles listed in the local census data were included when selecting clusters, with selected clusters replaced if they were located more than 90 minutes’ walk from the nearest point that could be reached by a 4-wheel-drive vehicle, or if there were security concerns.

Figure 1.

Evaluation unit boundaries, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

Verbal consent for examination was obtained and recorded electronically. Global positioning system (GPS) coordinates of each household were recorded, with examinations then carried out for all consenting household members who were 1 year of age or older, using 2.5× magnifying loupes. All data were recorded in a smartphone using a bespoke application developed for the GTMP.16 Absent household members were registered both on the smartphone and in a separate logbook, including information on where they had gone and when they were expected to return. After finishing all 30 households the teams returned to households where there had been absentees and if those individuals were present, they were invited to be examined.

Quality control

Two supervisors (experienced ophthalmologists who had been certified as GTMP grader trainers and had helped to train the Benishangul Gumuz graders) participated in fieldwork. Each team spent 1 day in every 5 field days with a supervisor. At the completion of each day’s fieldwork, coordinators, supervisors, graders and recorders met to discuss logistical challenges faced and suggest solutions and improvements.

Ethical considerations

Ethics clearance for the study was obtained from the Benishangul Gumuz Regional Health Bureau (13Ye/KK/03), the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health institutional review board, and the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (6319).

Graders and recorders explained the purpose of the survey to the members of each participating household, and assured prospective participants that all information obtained would be treated confidentially. Participants with active trachoma were provided with two tubes of 1% tetracycline eye ointment immediately after the examination. Those who needed further examination or treatment were referred to local health facilities. People who had trichiasis were registered and referred to the nearest health facility at which there was a trichiasis surgery service. In addition, individuals not included in the study were managed or referred as appropriate when they presented to a field team. In each community, after the completion of data collection, teams provided health education on trachoma.

Results

A total of 5828 households were sampled, from seven EUs covering 20 woredas. A total of 21,919 individuals were enumerated from these households, of whom 11,757 (53.6%) were female. A total of 7417 children aged 1–9 years were examined, of whom 56.7% were female, and a total of 9949 people aged 15 years or older were examined, of whom 62.4% were female. The median number of residents per household was five persons (interquartile range, IQR 3–6), and the mean age of those examined was 20.7 years. The median number of children aged 1–9 years per household was 2 (IQR 1–3). The baseline characteristics of those examined in each EU are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age distribution of survey participants, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

| Evaluation unit | Age, years | Examined, n | Absent, n | Refused, n | Other, n | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dangur, Wembera, Guba | 1–9 | 985 | 30 | – | – | 1015 |

| 15+ | 1442 | 148 | 1 | – | 1591 | |

| Pawe, Mandura | 1–9 | 955 | 26 | – | – | 981 |

| 15+ | 1382 | 285 | 3 | – | 1670 | |

| Bulen, Dibate | 1–9 | 1146 | 13 | – | – | 1159 |

| 15+ | 1494 | 252 | 3 | – | 1749 | |

| Bio Jiganifado, Sirba Abay, Kamashi, Yaso, Agelo Meti | 1–9 | 1204 | 25 | – | – | 1229 |

| 15+ | 1450 | 267 | 4 | – | 1721 | |

| Komesha, Sherkole, Menge, Kurmuk | 1–9 | 1194 | 17 | 2 | – | 1213 |

| 15+ | 1209 | 291 | 7 | 2a | 1509 | |

| Assosa | 1–9 | 806 | 21 | 4 | – | 831 |

| 15+ | 1505 | 389 | 15 | 2b | 1911 | |

| Bambasi, Maokom Special, Oda Beldigu | 1–9 | 1127 | 26 | – | – | 1153 |

| 15+ | 1467 | 237 | 3 | – | 1707 | |

| Total | 17,366 | 2027 | 42 | 4 | 19,439 | |

aKomesha, one individual with bilaterial phthisis bulbi, one individual who could not be examined.

bAssosa, two blind individuals.

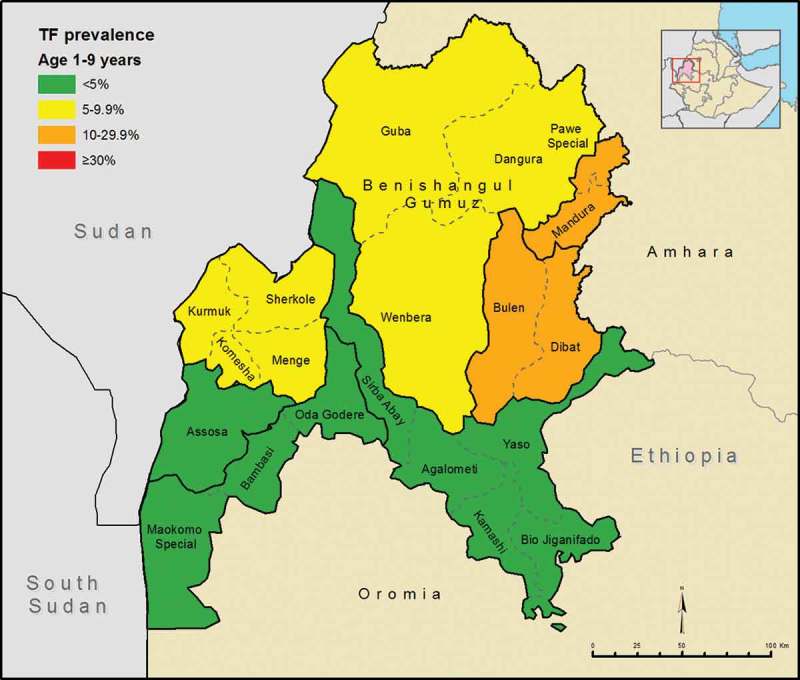

TF was present in 615 (8.3%) of the 7417 children aged 1–9 years examined. The overall age-adjusted prevalence of TF in those aged 1–9 years was 7.4%, with marked variation between EUs. EU-level age-adjusted TF prevalences are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

| Evaluation unit | Examined, n | TF, n (%) | Adjusteda TF, % (95% confidence interval)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danguar, Wembera, Guba | 985 | 55 (5.6) | 5.8 (3.1–9.4) |

| Pawe, Mandura | 955 | 180 (18.8) | 17.6 (11.7–25.5) |

| Bulen, Dibate | 1146 | 219 (19.1) | 15.2 (11.2–22.4) |

| Bio Jiganifado, Sirba Aby, Kamashi, Yaso, Agelo Meti | 1204 | 23 (1.9) | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) |

| Komesha, Sherkole, Menge, Kurmuk | 1194 | 66 (5.5) | 5.1 (3.1–7.5) |

| Assosa | 806 | 31 (3.8) | 2.8 (1.5–4.4) |

| Bambasi, Maokom Special, Oda Beldigu | 1127 | 41 (3.6) | 3.3 (2.1–4.7) |

aAdjusted for age using the Benishangul Gumuz census data from the Ethiopian National Census 2007.

bConfidence intervals obtained by bootstrapping age-adjusted cluster-level proportions.

Figure 2.

Distribution of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) prevalence in 1–9-year-olds at evaluation unit level, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

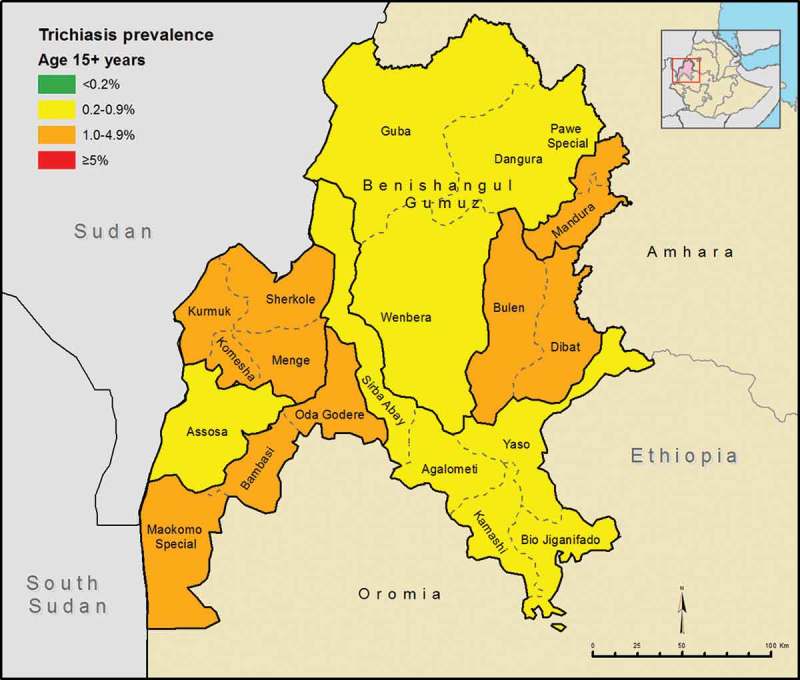

Overall, 251 cases of trichiasis were identified across all sites, of which 143 (57.0%) were unilateral and 108 were bilateral. We therefore identified a total of 359 trichiatic eyes in the population; all affected individuals were offered corrective surgery. One case of trichiasis was found in a child aged 1–9 years. Of those examined aged 15 years or older (n = 9949), 246 (2.5%) had trichiasis; 182 (74.0%) of these were female. The overall age- and sex-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in those aged 15 years or older was 1.3%. The EU-level sex- and age-adjusted trichiasis prevalences are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

Prevalence of trichiasis in those aged ≥15 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

| Evaluation unit | Examined, n | Trichiasis, n (%) | Adjusteda trichiasis %, (95% confidence interval)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danguar, Wembera, Guba | 1442 | 10 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

| Pawe, Mandura | 1382 | 71 (5.1) | 2.5 (1.6–3.4) |

| Bulen, Dibate | 1494 | 39 (2.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| Bio Jiganifado, Sirba Aby, Kamashi, Yaso, Agelo Meti | 1450 | 22 (1.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| Komesha, Sherkole, Menge, Kurmuk | 1209 | 34 (2.8) | 1.8 (0.8–3.0) |

| Assosa | 1505 | 41 (2.7) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) |

| Bambasi, Maokom Special, Oda Beldigu | 1467 | 29 (2.0) | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) |

aAdjusted for sex and age in 5-year age groups using the Benishangul Gumuz census data from the Ethiopian National Census 2007.

bConfidence intervals obtained by bootstrapping age-adjusted cluster-level proportions.

Figure 3.

Distribution of trichiasis prevalence in ≥15-year-olds at evaluation unit level, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia, 2013–2014.

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of TF (≥10% in 1–9-year-olds) in two EUs (four woredas, estimated total rural population 203,690) of Benishangul Gumuz. Two other EUs (seven woredas, estimated total rural population 333,087) had TF prevalences between 5.0% and 9.9%. All seven EUs surveyed had trichiasis prevalences in adults significantly over the 0.2% WHO threshold for trachoma elimination in those aged 15 years and older.17,18 The estimates of TF and trichiasis prevalence from these surveys are very different from the results of the Ethiopian National Survey of Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma in 2005–2006, which reported an estimated TF prevalence of 0.9% and an estimated trachomatous trichiasis prevalence of 0.1% for this region as a whole. The 2005–2006 survey primarily aimed to provide national-level estimates, and included only a few Benishangul Gumuz villages, and it is possible that the villages selected at that time happened not to be representative of the region. The authors of the report on the 2005–2006 survey noted, as limitations of their work, that strict implementation of planned procedures had been difficult in remote villages, and that in Benishangul Gumuz region, a large influx of healthy immigrants from neighboring Sudan may have contributed to the overall low recorded trachoma prevalence.19

In the present set of surveys, two EUs covering four woredas had high prevalences of TF in children aged 1–9 years (Bulen and Dibate, 15.2%, and Pawe and Mandura, 17.6%) and require implementation of the A, F and E components of the SAFE strategy (surgery for trichiasis, antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvement), including EU-wide mass administration of azithromycin, for at least 3 years before re-survey. Intervention planning should begin for these woredas as soon as possible. Implementation of an elimination program in Benishangul Gumuz will require significant funds, plus mechanisms to channel these funds to the coalface. All woredas in the region require emphasis on the F and E components of trachoma control.

We estimated that 1.3% of the adult population of Benishangul Gumuz are likely to have trichiasis and as a result are at imminent risk of incurable progressive visual impairment. To address such a significant potential trichiasis surgical backlog will require considerable investment to recruit and train eye care workers so that these corrective surgeries can be carried out in a timely manner. A robust plan to seek investment and coordinate efforts is needed. A recent randomized controlled trial20 showed significantly lower rates of post-operative trichiasis in patients undergoing posterior lamellar, as opposed to bilamellar, tarsal rotation; this suggests that the former technique should be the one selected for roll-out in Benishangul Gumuz, although previously the WHO has advocated the use of either procedure.21

Although trachoma is clearly a significant public health problem in Benishangul Gumuz, there was a higher proportion of low TF prevalence (<10%) woredas in Benishangul Gumuz than in other regions of Ethiopia. The reasons for this are unclear, but local health workers report that social housing and sanitation were made widely available in this region following large-scale resettlement of people from elsewhere in Ethiopia in the 1980s, and this may be part of the explanation. The Benishangul Gumuz woredas with the highest prevalences (of both TF and trichiasis) were those bordering the Amhara region, a region thought to have the highest prevalence of active trachoma in the world.22,23 The possible explanations for the very high prevalence of trachoma in Amhara, and the relative paucity of disease in neighboring Benishangul Gumuz, are interesting avenues for future research.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.

Funding Statement

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bourne RRA, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1(6):e339–e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mabey DCW, Solomon AW, Trachoma Foster A.. Lancet 2003;362(9379):223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fraser-Hurt N, Mabey D.. Trachoma. Clin Evid (Online) 2003;(9):745–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Trachoma: Fact Sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mpyet C, Lass BD, Yahaya HB, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in Kano State, Nigeria. PLoS One 2012;7 (7):e40421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. J-F Schémann, Sacko D, Malvy D, et al. Risk factors for trachoma in Mali. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zerihun N. Trachoma in Jimma zone, south western Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health 1997;2:1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alene GD, Abebe S.. Prevalence of risk factors for trachoma in a rural locality of north-western Ethiopia. East Afr Med J 2000;77:308–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brechner RJ, West S, Lynch M.. Trachoma and flies. Individual vs environmental risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960) 1992;110:687–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Courtright P, Sheppard J, Lane S, et al. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol 1991;75:322–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. West S, Lynch M, Turner V, et al. Water availability and trachoma. Bull World Health Organ 1989;67:71–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polack S, Kuper H, Solomon AW, et al. The relationship between prevalence of active trachoma, water availability and its use in a Tanzanian village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100:1075–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, et al Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:982–1011, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. Prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2008;21:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Central Statistical Agency Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 19–20 July 2010 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization Report on the 2nd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. National Survey on Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma in Ethiopia, Vol 21. Addis Ababa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Habtamu E, Wondie T, Aweke S, et al. Posterior versus bilamellar tarsal rotation surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4(3):e175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello S, et al. Trichiasis surgery for trachoma (2nd ed). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berhane Y, Alemayehu W, Bejiga A.. National Survey on Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith J, Mann R, Haddad D, et al. Global atlas of trachoma: an open-access resource on the geographical distribution of trachoma. Atlanta, GA: International Trachoma Initiative, 2015, www.trachomaatlas.org.