Abstract

Part of the symptomatology of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are alterations in arousal and reactivity which could be related to a maladaptive increase in the automated sensory change detection system of the brain. In the current EEG study we investigated whether the brain’s response to a simple auditory sensory change was altered in patients with PTSD relative to trauma-exposed matched controls who did not develop the disorder. Thirteen male PTSD patients and trauma-exposed controls matched for age and educational level were presented with regular auditory pure tones (1000 Hz, 200 ms duration), with 11% of the tones deviating in both duration (50 ms) and frequency (1200 Hz) while watching a silent movie. Relative to the controls, patients who had developed PTSD showed enhanced mismatch negativity (MMN), increased theta power (5–7 Hz), and stronger suppression of upper alpha activity (13–15 Hz) after deviant vs. standard tones. Behaviourally, the alpha suppression in PTSD correlated with decreased spatial working memory performance suggesting it might reflect enhanced stimulus-feature representations in auditory memory. These results taken together suggest that PTSD patients and trauma-exposed controls can be distinguished by enhanced involuntary attention to changes in sensory patterns.

Introduction

Up to 80% of the general population encounters severe adverse life events. For some, these events can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a common disorder with a lifetime prevalence of about 7%1–3. Diagnostic criteria of PTSD are intrusions, avoidance of distressing trauma-related stimuli, hyperarousal, and negative alterations in cognitions, and mood (see DSM-54) and some patients show attention and memory deficits5,6. In particular, the symptom cluster of alterations in arousal and reactivity implies that PTSD patients typically respond to reminders of traumatic events - but also to neutral stimuli - with exaggerated startle response and hypervigilance4. High prevalence, difficulties in treatment7,8, and often debilitating consequences of the disorder illustrate the great need for investigating the underlying cognitive mechanisms of traumatic stress responses for PTSD. In the current study we investigated whether the brain’s response (measured using EEG) to a simple auditory sensory change was altered in patients with PTSD relative to trauma-exposed matched controls who did not develop the disorder.

The mismatch negativity (MMN) is an event-related potential (ERP) in response to deviant stimuli that differ from a sequence pattern of standard stimuli preceding it9. It represents the ability to automatically and without conscious effort compare among series of tones, to detect auditory changes, and to switch attention to potentially important events in the unattended auditory environment9–11. The MMN provides a neurophysiological index of auditory information processing, perceptual accuracy, learning, and memory; all related to automatic processing and largely not under direct control12,13. The MMN plays an important role in clinical research: Weaker MMN can predict psychosis onset14–16, perceptual and cognitive abnormalities in schizophrenia17–19, and impaired auditory frequency discrimination in dyslexia20. Increases in MMN amplitudes, by contrast, were found in adults with Asperger’s syndrome21,22, closed head injury23, alcoholism24,25, children with major depression26, and sleep disorders27. Stronger MMN responses for those patient groups may reflect enhanced discrimination of sound pattern22 and/or increased involuntary attention switching in response to auditory change13.

For PTSD, the MMN remains one of the least studied ERP components and results remain inconsistent (see Javanbakht28). Enhanced MMN has been previously found in high school students who have experienced an earthquake29 and in women with sexual assault-related PTSD30. Those effects may reflect enhanced involuntary attention to auditory deviations in PTSD as a result of chronic hyperarousal and hypervigilance. By contrast, some researchers found reduced MMN in PTSD, which has been interpreted as compensation for chronic hyperarousal31 or as difficulty to discriminate relevant from irrelevant stimuli due to overall neural hyperactivity32,33. So far, investigations on MMN in PTSD have been limited to specific target groups (high school students) or specific trauma etiologies (earthquake in China) and controls were not matched to the patients. One of our aims is therefore to study same-sex adults diagnosed with PTSD and trauma-exposed controls, matched by age, gender, and education, to investigate group differences in the MMN in response to auditory oddball stimuli.

Event-related potentials such as the MMN reflect change in the EEG over time and are phase locked to the onset of the stimuli. A shortcoming of the MMN as a clinical tool is that it cannot be reliably identified in every individual34. As such, another objective of the current study was to examine the induced changes in (i.e. responses in the EEG signal that are time-locked but not phase locked to events) elicited by the onset of deviant stimuli, as a new potential tool for characterizing and predicting PTSD; specifically, the suppression of oscillatory alpha band activity. The depth of stimulus processing in a relevant region is indicative by alpha suppression35,36 with the amount of alpha suppression reflecting the resources allocated to processing the stimulus37. Stimulus induced alpha modulation in healthy population can be reliably identified within individuals, and covaries with variability in attentional performance38,39.

Investigations into the alpha suppression effect have been applied to research into the neurobiological underpinnings of psychiatric disorders. For example, deviations in alpha suppression have been reported for schizophrenia40,41, bipolar disorder, depression42,43, and obsessive-compulsive disorder44,45. These studies suggest that induced oscillatory alpha activity—even in simple cognitive tasks—may be a valuable biomarker for psychiatry. Here, we will extend current findings and investigate induced oscillatory alpha in PTSD. Research in into oscillatory brain activity in PTSD has been limited to ongoing or resting oscillatory activity. For example, alpha-theta-ratio neurofeedback therapy has shown some degree of effectiveness for Vietnam veterans with combat-related PTSD46 and for patients with anxiety disorders, where alpha power changed in proportion to anxiety levels (for review see Moore47). Magnetic resonance therapy inducing alpha power increase resulted in decreases in PTSD symptom severity48. Finally, alpha asymmetry49, alpha peak frequency50, and power of right hemisphere frontal alpha correlated with PTSD symptom severity49,51 as well as executive task performance51.

Few studies have directly investigated alpha power changes in PTSD and results remain inconclusive49,52,53. Differences in oscillatory alpha activity during resting state were found among PTSD groups with different trauma etiology. Combat veterans with PTSD were compared to Chernobyl accident survivors with PTSD and showed decreased alpha and increased beta and theta power. However, when compared to controls without the disorder no effects for PTSD were found54. Begić et al. found increases in the upper alpha, but not in the lower alpha band, in PTSD55, while in a later study they found suppression of low alpha over frontal, central and occipital channels56. Increased alpha power was found during non-REM sleep for PTSD compared to trauma controls (Olff, personal communication, paper submitted). Besides those resting state EEG studies, a pilot MEG study on nine females with PTSD was conducted and showed reduced alpha power in left Broca area, insula and premotor cortex during tape-recorded auditory trauma imagery compared to neutral imagery57. Thus, most research into oscillatory power changes has focused on brain activity during trauma-exposure or at rest. There is strong evidence that hyper-responsivity in PTSD is not restricted to trauma-related stimuli or trauma-related thoughts during rest (see Casada et al.58 vs. Shin et al.59. PTSD patients show disadvantages in cognitive performance, e.g. tasks that involve attention and memory for neutral information60,61. If we detected neural hyperresponsiveness to neutral stimuli that are trauma-unrelated, we could contribute to a better understanding of deviations in automatic attention in PTSD patients. Anomalies in involuntary bottom-up attention in PTSD could explain attention-related problems on everyday tasks.

To investigate this, participants’ EEG was recorded while they were presented with neutral tones according to a simple auditory oddball task while watching a silent movie.

In the current study we investigated whether the brain’s evoked and induced responses to the occurrence of an oddball auditory stimuli were altered in PTSD patients relative to trauma-exposed matched controls. We predicted alterations of the MMN, increased theta band power and stronger suppression of alpha activity after deviant (vs. standard) tones in the PTSD group. We also examined if any of the brain responses correlated with PTSD symptom severity (assessed by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-4; CAPS62) and cognitive task performance (assessed by CANTAB subtests).

Methods

Participants

Thirteen male PTSD patients (mean age = 46.7) were recruited from an outpatient psychiatric clinic. All PTSD patients were diagnosed with chronic PTSD (symptoms duration > 3 months; CAPS score ≥ 45). Thirteen trauma exposed male controls (mean age = 43.5) were matched to the patients based on age and education and met the A criterion (trauma-exposure) for PTSD as defined by the DSM-IV, but no other psychiatric disorders. Controls were recruited from a previous cohort study on prediction and prevalence in PTSD patients from trauma units and through advertising. All participants met the following criteria: no suicidal risk, no neurological impairments, no primary diagnosis of severe depressive disorder, and no other psychiatric disorder (as defined by DSM-IV/ MINI plus63), normal hearing, and normal or corrected to normal vision. See also Table 1 for participant characteristics. All participants gave written informed consent and received 10 € plus a compensation for their travel expenses. The experiment conformed with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the local medical ethics committee of the Academic Medical Centre of Amsterdam.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| PTSD (N = 13) | Matched controls (N = 13) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.7 | 43.5 |

| Gender | Male | Male |

| Educational level | ||

| Low | 0% | 0% |

| Medium | 38% | 38% |

| High | 62% | 47% |

| Academic | 0% | 15% |

| CAPS (Mean score) | 64.8 | 1.3 |

| Re-experiencing | 17.7 | 0.7 |

| Avoidance | 22.2 | 0.0 |

| Hyperarousal | 24.9 | 0.7 |

| Cognitive performance (CANTAB) | ||

| Sensorimotor (MOT error) | 12,4% | 12.6% |

| Response inhibition (SST SSD) | 259.2 ms | (459.0 ms)* |

| Response inhibition (SST SSRT) | 176.3 ms | (164.1 ms)* |

| Working memory (SWM error) | 28.1% | 24.9% |

*Note: Due to technical issues, SST performance in the control group is based on N = 7.

Auditory paradigm and clinical assessment

The participants were presented with a pseudorandomized sequence of 2000 tone stimuli with a trial duration of 1000 ms (Presentation Software, Neurobehavioral Systems Inc., Albany, CA, USA). The standard tone had a frequency of 1000 Hz and duration of 100 ms. A tone that varied in frequency (1200 Hz, deviant) and duration (50 ms) was added to the sequence and was presented in 11% of trials but never presented successively. During the presentation of the tones (30 mins), the participants watched a neutral silent movie with subtitles (The life of birds, BBC nature documentary). After the experiment structured interviews were administered after which participants performed additional cognitive tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB). These included the Dutch versions of the M.I.N.I plus to rule out psychiatric disorders63, the life events checklist (LEC62) to assess potentially traumatic events in a respondent’s lifetime, and the Clinician-administered PTSD scale for PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity assessment (CAPS62). Administered CANTAB subtests were the Motor Screening Task (MOT), the Stop Signal Task (SST) to quantify response inhibition and the Spatial Working Memory (SWM) test.

Electrophysiological Recordings, Pre-processing and Data Analysis

EEG was recorded using a WaveGuard cap system developed by ANT, with 64 shielded Ag/AgCl electrodes (Advanced Neuro Technology B.V.) following the international ‘10/20’ system. To record horizontal and vertical EOG, electrodes were applied to the outer canthi of the eyes and between supraorbital and infraorbital around the right eye. EEG was continuously sampled at 512 Hz with an online average reference and impedances were kept under 100 kΩ. All recordings were done with ASA software (Advanced Neuro Technology B.V.).

Pre-processing of the EEG signal was performed using EEGlab 13.3.2b64. The data was resampled to 256 Hz, band-pass filtered between 1 to 30 Hz, and epoched into 1400 ms windows with a 500 ms prestimulus period. For baseline correction an interval of −100 to 0 ms was used. Further analysis of standard tones was restricted to those preceding a deviant tone, since a standard following a deviant tone may be considered deviant. Next, epochs were checked for large artifacts (±75 μV), ignoring high voltage ocular artifacts at frontal pole & anterior frontal locations and visually checked for artifacts. Independent component analysis (ICA) using the logistic infomax ICA algorithm of Bell & Sejnowski65 and prior principal component analysis dimension reduction to 30 components. Components containing ocular artifacts were removed and the remaining source-data was back-projected. On average 2.2 and 2.1 components were rejected for controls and patients respectively. Remaining trials that still contained nonbiological artifacts with amplitudes exceeding ±75 μV in any of the channels, were excluded from the analysis and the dataset was visually inspected a last time before entering the statistical analysis. The mean percentage of rejected trials across subjects was 3.2% for controls 4.6% for patients. To investigate the effect of the deviant tone as opposed to the standard tones the datasets were split up into the two experimental conditions again.

Mismatch Negativity Analysis

To analyse MMN, an ERP analysis was performed using the open source FieldTrip toolbox for MatLab (version 20140306)66. ERPs were computed for each individual and baseline corrected based on the interval 100 ms prior to auditory stimulus for both trial types separately. Based on the grand-averaged ERPs, a fixed time interval of 100 to 160 ms was chosen to determine the mean peak amplitude of MMN effects. Statistical analysis of the ERP amplitude was conducted on the average of electrodes FC1/ FC2, where the overall mean peak amplitude collapsed across groups appeared to be maximal. We here employed a repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of group (PTSD vs. Control) and tone (standard vs. deviant).

Time-Frequency analysis of oscillatory power

To analyse oscillatory power, a time-frequency decomposition of the EEG data was performed to investigate group differences in temporo-spectral dynamics of oscillatory modulations induced by the onset of the deviant stimuli. Using the Fieldtrip software package66 function ft_freqanalysis_mtmconvol, time-frequency representations (TFR) of power were obtained per trial (defined as −0.5 s to 0.9 s after stimulus onset) by sliding a single hanning window with an adaptive size of two cycles over the data (ΔT = 2/f). Power was analysed from 2 to 30 Hz in steps of 1 Hz steps for every 10 ms. A difference TFR of deviant vs. standard post-stimulus activity was computed by subtracting the grand average TFR of standard trials from the grand average TFR of deviant trials. Statistical analyses on the difference TFR were conducted separately for theta (5–7 Hz), low alpha (8–12 Hz), and upper alpha (13–15 Hz) frequency bands. The selection of these frequency bands was based on looking at the grand-averaged data (collapsed across groups/conditions) as well prior literature37,67. Power from these frequency-bands was subjected to cluster-level permutation tests68 (as described below) to statistically assess any difference between the PTSD and control group across all time points from 0 to 500 ms post-stimulus.

The cluster permutation procedure was used to control for multiple comparisons68. This procedure uses a standard test (i.e. the two-tailed paired t-tests computed for channel-time pairs) and notes the significance at an arbitrary but fixed level (here, p < 0.05). Clusters based on this threshold (i.e. p < 0.05) are identified that show significant effects adjacent in space (channels) and time. Spatial clustering used the ‘triangulation’-method, which is based on direction of effect and spatial proximity. For each cluster, the sum of all significant t-values is noted (cluster statistics). Next, the same is done after randomly selecting 1000 permutations of group values (PTSD vs. controls), extracting the maximum summed-t value of the randomly appearing spatial-time clusters (reference statistics). The p-value is based on comparing the observed cluster statistics to the reference statistics. This p-value controls the false alarm rate and was kept below 5% for each significant cluster.

Correlation Analysis

To assess the relation between modulations of the EEG by auditory deviance and cognitive performance we correlated alpha suppression and theta power increase in response to deviant tones averaged over the location and period of interest with cognitive performance on the CANTAB. All values were log transformed to correct for possible data skewness and wide distributions. Then we computed the Pearson’s correlation coefficients of the detected power effects with individual stop signal reaction time and between errors on the spatial working memory task. Due to technical issues performance of six participants on the CANTAB tests could not be reliably quantified and therefore the control group was excluded from the correlation analysis.

Using the same procedure, an equivalent analysis was performed to assess the relation between observed EEG effects and PTSD symptom severity by correlating averaged EEG power data with the CAPS scores.

Results

Stronger MMN and late positivity for PTSD in response to auditory deviance

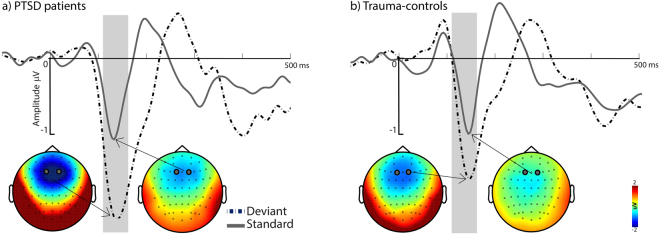

To investigate groups differences in MMN we contrasted ERPs evoked by the onset of the deviant vs. standard tones. Irrespective of group, negative peak amplitudes were more pronounced after deviant tones [main effect Tone: F(1,12) = 65.47; p < 0.001, η² = 0.85] which confirmed a significant MMN effect for our experimental setup. An interaction effect of Tone x Group revealed a stronger MMN effect for PTSD (M = −1.08 μV) compared to their matched controls (M = −0.53 μV) [F(1,12) = 20.246; p < 0.001, η² = 0.63, see Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

The grand-average ERP waveforms (FC1/FC2) after deviant and standard tones for PTSD (a) patients and (b) trauma-exposed matched controls (right panel). ERP waveforms and topographies show a larger and earlier negative peak (i.e. mismatch negativity) in PTSD patients compared to the controls.

Alpha and theta power modulations

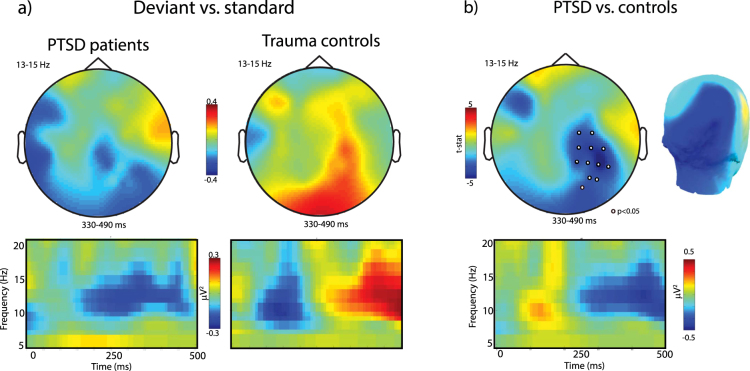

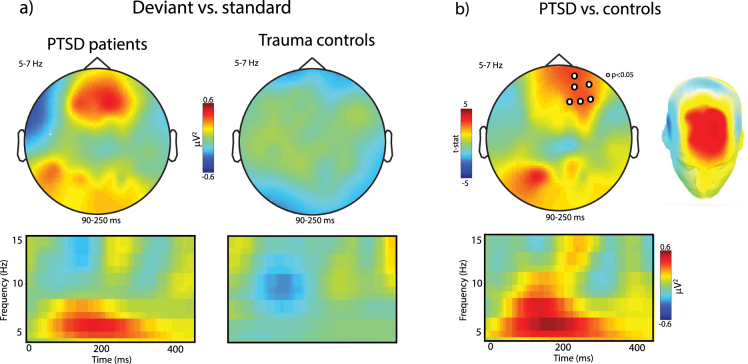

To investigate the differences in oscillatory activity induced by auditory deviance between the PTSD and control groups we subjected the deviant minus standard post-stimulus oscillatory power in the theta and alpha range to a cluster-based permutation test (described above) for all time points between 0 and 500 ms after stimulus onset. Upper alpha power was significantly more suppressed in the PTSD group relative to the controls within the time window of 330–490 ms (p < 0.05) post stimulus over a cluster comprising right centro-parietal and occipital channels (see Fig. 2). In addition we found that post-stimulus theta power was significantly greater in the PTSD group relative to controls 90–250 ms post-stimulus (p < 0.05, see Fig. 3) over a cluster of frontal electrodes.

Figure 2.

(a) Topographies (upper panel) and time-frequency representations (TFR, lower panel) of upper alpha band power after deviant as opposed to standard tones. (b) Greater alpha suppression at 330–490 ms after deviant (vs. standard) tones over posterior electrodes in PTSD patients compared to trauma-exposed matched controls suggests hyperresponsiveness to stimulus change, increased auditory processing, and/or stronger stimulus-feature representations in auditory sensory memory in PTSD. Note that topographies were averaged over time window and TFRs over electrodes where a cluster-based permutation test detected a significant group effect in response to auditory stimulus change.

Figure 3.

(a) Topographies (upper panel) and time-frequency representations (TFR, lower panel) of theta band power (5–7 Hz) over frontal channels at 90–250 ms after deviant as opposed to standard tones. (b) Compared to controls, PTSD patients showed increased synchronization in theta band power over (right) fronto-central channels which indicates enhanced automatic pre-attentive auditory processing and hypersensitive auditory discrimination ability in PTSD in response to deviant (vs. standard) tones.

Alpha suppression effect related to impaired memory performance

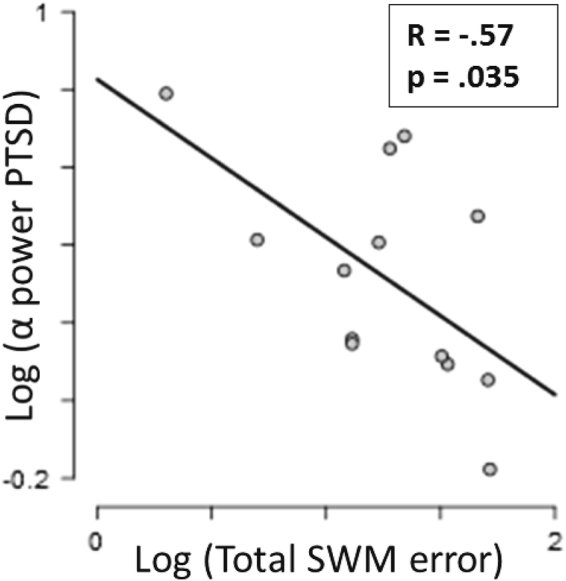

Upper alpha power in PTSD in response to the deviant tones correlated negatively with their individual working memory performance (r = − 0.57, N = 13, p = 0.035, see Fig. 4) at the time of recording. All other correlations were not significant.

Figure 4.

Upper alpha power in PTSD following the deviant tones correlated negatively with patients’ working memory performance. Alpha suppression in response to deviating sounds was related to increasing between errors on the spatial working memory task.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating neural responses to deviant vs. standard tones in PTSD patients compared to trauma-exposed gender-, age- and education-matched controls. Participants were presented with an auditory oddball paradigm with 11% of the tones deviating in duration (50 vs. 100 ms) and frequency (1200 vs. 1000 Hz) while watching a silent movie. We found that PTSD patients showed stronger MMN amplitudes relative to controls. In addition, compared to controls, tone deviance induced a suppression of the upper alpha band and increased theta synchronisation in the PTSD group. Alpha power suppression in PTSD was related to impaired individual working memory performance at the time of recording.

Thus far findings of alpha modulations in PTSD have focused on resting state measurements and have remained inconclusive49,52–56. Taking these into consideration, while at rest, oscillatory alpha power in PTSD might vary depending on the trauma etiology of the patient group. Patients might either experience the experimental setting as threatening or be more extensively focused on internal processes. Accordingly, in line with our findings, attention to external events would explain results of alpha suppression in PTSD during rest, while inner attention (re-experiencing trauma/ recollection of traumatic memory) would explain findings of increased alpha in PTSD.

However, alpha/beta oscillations not only reflect attentional processing, but especially upper alpha band modulations play a role in memory-related processes69–72. In this study, alpha power suppression induced by deviant stimuli in PTSD was related to impaired working memory performance. Alpha power modulations have previously been observed during attention allocation for memory retrieval and auditory working memory retention which are related to memory performance in healthy participants73–75. Therefore, given its latency and location, the present auditory-deviance related alpha suppression effect in PTSD might not only reflect attentional mechanisms, but as well account for enhanced auditory stimulus evaluation in PTSD. Patients with PTSD may show enhanced comparison of deviating auditory stimuli to auditory working memory. Since desynchronisation in the upper alpha band has been related to semantic LTM processes71 the observed effects even might reflect unconscious automatic retrieval of trauma-related auditory memory in PTSD to compare the salient stimulus with35,36,76. This remains to be tested. If true, continuous stimulus comparison to auditory working memory would exhaust and disturb everyday activity that requires memory retrieval which explain the observed correlations of alpha suppression with memory impairment, and the impaired functioning of PTSD patients in daily life.

In sum, increased occipito-parietal alpha suppression and enhanced late positivity after salient tones in PTSD might reflect hypersensitivity to stimulus deviance and abnormalities in the (preconscious) auditory sensory memory. Suppressed alpha power and resulting difficulties in suppression of attentive processing of deviating auditory information could make PTSD patients more prone to automatically detect auditory stimulus change, and to compare those stimuli to auditory short-term memory. This might explain PTSD-specific symptoms of hyperarousal, hypervigilance, memory impairments and distraction from daily tasks.

Our findings of increased frontal theta and increased mismatch negativity in response to stimulus deviance in the PTSD group are in line with previous findings of theta synchronisation in PTSD55,77 as well as findings of theta synchronisation in combination with auditory MMN effects in healthy controls. In all three studies those theta effects appeared in about the same time frame and at similar channels locations78–80. Transient theta as the dominant frequency band during auditory stimulus discrimination has been found to characterize deviant stimulus processing while interfering activations from other frequency networks are minimized81,82. MMN amplitudes and frontal theta power have been found to be correlated83. Both have been found to be reduced in schizophrenia, which was interpreted as reduced auditory discrimination and shortcomings in prediction and evaluation of stimulus salience83–85. While auditory discrimination is impaired in schizophrenia18,86, PTSD patients might be hypersensitive to auditory stimulus changes. Therefore, the present findings of theta power increases and increased MMN in the PTSD groups most likely reflect hypersensitive early discrimination and change detection processing in the frontal regions. Enhanced automatic pre-attentive auditory processing might explain hypersensitive auditory discrimination ability in PTSD.

The amplitude of the MMN can differ, depending on how prevalent stimulus characteristics between deviant and standard are87. The deviant stimuli in the given experiment differed in both, frequency and duration which might explain the early onset of MMN. The average peak onset appears slightly earlier in the patients group (Fig. 1) which could be explained by symptoms of general hypersensitivity/hyperarousal in PTSD. Mixed results of MMN increase/decrease in PTSD might be explained by the heterogeneity of the disorder. Patients with major symptoms of avoidance (flight-response) may show diminished MMN while patients with stronger symptoms of hyperarousal (like military/police officers) might show increased MMN (see Cornwall et al. 2007). This however, remains speculative and more research is needed for clarification.

Limitations of this study would be a rather small sample size that might have limited the power of correlations of EEG effects with PTSD symptom severity (sub-)scores.

Our findings point to a dysregulation in the suppression of task-irrelevant, but salient auditory information in PTSD. While an increased MMN during stimulus perception indicate increased involuntary bottom-up attention switches towards auditory stimulus perception, alpha suppression occurs slightly later and point towards a dysregulation in the suppression of stimulus evaluation at a later stage of stimulus processing. Hyperarousal states can intensify automatic sensory processes that bypass cognitive appraisal and careful evaluation of current perceptions61. Here we show that PTSD patients and trauma-exposed controls who do not develop the disorder can be distinguished by their cognitive processing of stimuli that are neutral and unrelated to their trauma. In the search for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions targeting specific PTSD symptoms88 this study may add to clarifying the neurobiological deviations behind debilitating hyperarousal symptoms interfering with daily functioning in the life of PTSD patients.

Acknowledgements

A.M. was supported by a VENI grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Author Contributions

A.M. and M.O. designed experiment, S.vB. and K.A.B. performed research, K.A.B. analyzed data and prepared the main manuscript and figures, A.M., D.J.A., M.O. and S.v.B. reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Ali Mazaheri and Miranda Olff jointly supervised this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Katrin A. Bangel, Email: katrin01@gmail.com

Ali Mazaheri, Email: a.mazaheri@bham.ac.uk.

References

- 1.de Vries G-J, Olff M. The lifetime prevalence of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. J. Trauma. Stress. 2009;22:259–267. doi: 10.1002/jts.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yehuda R. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:108–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2013).

- 5.Vasterling JJ, Brailey K, Constans JI, Sutker PB. Attention and memory dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:125–133. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.12.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasterling JJ, et al. Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.16.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelmendi B, et al. PTSD: from neurobiology to pharmacological treatments. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:31858. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.31858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnyder, U. et al. Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Näätänen R, Gaillard AWK, Mantysalo S. Early Selective Attention Effect on Evoked Potential Reinterpreted. Acta Psychol. (Amst). 1978;42:313–329. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(78)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giard MH, Perrin F, Pernier J, Bouchet P. Brain Generators Implicated in the Processing of Auditory Stimulus Deviance: A Topographic Event‐Related Potential Study. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:627–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Näätänen R, Paavilainen P, Rinne T, Alho K. The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: A review. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007;118:2544–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baddeley A. Working Memory - the Interface between Memory and Cognition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1992;4:281–288. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1992.4.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Näätänen R, Escera C. Mismatch negativity: clinical and other applications. Audiol. Neurootol. 2000;5:105–110. doi: 10.1159/000013874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkinson RJ, Michie PT, Schall U. Duration mismatch negativity and P3a in first-episode psychosis and individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;71:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodatsch M, et al. Prediction of psychosis by mismatch negativity. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Näätänen R, Shiga T, Asano S, Yabe H. Mismatch negativity (MMN) deficiency: A break-through biomarker in predicting psychosis onset. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015;95:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javitt DC, Shelley AM, Ritter W. Associated deficits in mismatch negativity generation and tone matching in schizophrenia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1733–1737. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javitt DC, Sweet RA. Auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia: integrating clinical and basic features. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:535–550. doi: 10.1038/nrn4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Näätänen R, Kähkönen S. Central auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia as revealed by the mismatch negativity (MMN) and its magnetic equivalent MMNm: a review. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:125. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldweg T, Richardon A, Watkins S, Foale C, Gruzelier G. Impaired Auditroy frequency Discrimination in Dyslexia detected with Mismatch evoked potentials American Neurological Association, 45. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:495–503. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199904)45:4<495::AID-ANA11>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kujala T, Lepistö T, Nieminen-Von Wendt T, Näätänen P, Näätänen R. Neurophysiological evidence for cortical discrimination impairment of prosody in Asperger syndrome. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;383:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kujala T, et al. Atypical pattern of discriminating sound features in adults with Asperger syndrome as reflected by the mismatch negativity. Biol. Psychol. 2007;75:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaipio ML, et al. Increased distractibility in closed head injury as revealed by event-related potentials. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1463–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200005150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahveninen J, Escera C, Polo MD, Grau C, Jaaskelainen IP. Acute and chronic effects of alcohol on preattentive auditory processing as reflected by mismatch negativity. Audiol. Neurootol. 2000;5:303–311. doi: 10.1159/000013896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polo MD, et al. Electrophysiological evidence of abnormal activation of the cerebral network of involuntary attention in alcoholism. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003;114:134–146. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00336-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lepistö T, et al. Auditory event-related potential indices of increased distractibility in children with major depression. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004;115:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gumenyuk V, et al. Shift work sleep disorder is associated with an attenuated brain response of sensory memory and an increased brain response to novelty: an ERP study. Sleep. 2010;33:703–713. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javanbakht L, Liberzon I, Amirsadri A, Gjini K. Event-related potential studies of post-traumatic stress disorder: A critical review and synthesis. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2013;44:76–77. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge Y, Wu J, Sun X, Zhang K. Enhanced mismatch negativity in adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2011;79:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan CA, Grillon C. Abnormal mismatch negativity in women with sexual assault- related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:827–832. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menning H, Renz A, Seifert J, Maercker A. Reduced mismatch negativity in posttraumatic stress disorder: A compensatory mechanism for chronic hyperarousal? Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2008;68:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felmingham KL, Bryant RA, Kendall C, Gordon E. Event-related potential dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder: The role of numbing. Psychiatry Res. 2002;109:171–179. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolb B, Cioe J. Recovery from early cortical damage in rats. IX. Differential behavioral and anatomical effects of temporal cortex lesions at different ages of neural maturation. Behav. Brain Res. 2003;144:67–76. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cacace AT, McFarland DJ. Quantifying signal-to-noise ratio of mismatch negativity in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;341:251–255. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klimesch W, Sauseng P, Hanslmayr S. EEG alpha oscillations: The inhibition-timing hypothesis. Brain Res. Rev. 2007;53:63–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen O, Mazaheri A. Shaping Functional Architecture by Oscillatory Alpha Activity: Gating by Inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010;4:186. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Diepen RM, Mazaheri A. Cross-sensory modulation of alpha oscillatory activity: suppression, idling, and default resource allocation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017;45:1431–1438. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazaheri A, et al. Functional Disconnection of Frontal Cortex and Visual Cortex in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazaheri A, DiQuattro NE, Bengson J, Geng JJ. Pre-stimulus activity predicts the winner of top-down vs. bottom-up attentional selection. PLoS One. 2011;6:16243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begić D, Hotujac L, Jokić-Begić N. Quantitative EEG in schizophrenic patients before and during pharmacotherapy. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41:166–170. doi: 10.1159/000026650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merrin EL, Floyd TC. Negative symptoms and EEG alpha activity in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1992;8:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90056-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kano K, Nakamura M, Matsuoka T, Iida H, Nakajima T. The topographical features of EEGs in patients with affective disorders. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1992;83:124–129. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(92)90025-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller A, et al. Regional patterns of brain activity in adults with a history of childhood- onset depression: Gender differences and clinical variability. Am. J. Psychiat. 2002;159:934–940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciesielski KT, et al. Dissociation between MEG alpha modulation and performance accuracy on visual working memory task in obsessive compulsive disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;28:1401–1414. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leocani L, et al. Abnormal Pattern of Cortical Activation Associated With Voluntary Movement in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001;158:140–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peniston VA MedicaJ Cemcr EG, Lyon Colorado Paul Kulkosky FJ. Alpha-Theta Brainwave Neuro-Feedback for Vietnam Veterans with Combat- Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Med. Psyc~OIherapy. 1991;4:7–60. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore NC. A review of EEG biofeedback treatment of anxiety disorders. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2000;31:1–6. doi: 10.1177/155005940003100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taghva, A. et al. Magnetic Resonance Therapy Improves Clinical Phenotype and EEG Alpha Power in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Trauma Mon. 20 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kemp AH, et al. Disorder specificity despite comorbidity: Resting EEG alpha asymmetry in major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychol. 2010;85:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahbeh H, Oken BS. Peak high-frequency HRV and peak alpha frequency higher in PTSD. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 2013;38:57–69. doi: 10.1007/s10484-012-9208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabe S, Zöllner T, Maercker A, Karl A. Neural correlates of posttraumatic growth after severe motor vehicle accidents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006;74:880–886. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gordon E, Palmer DM, Cooper N. EEG Alpha Asymmetry in Schizophrenia, Depression, PTSD, Panic Disorder, ADHD and Conduct Disorder. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2010;41:178–183. doi: 10.1177/155005941004100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lobo I, et al. EEG correlates of the severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A systematic review of the dimensional PTSD literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;183:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loganovsky KN, Zdanevich NA. Cerebral basis of posttraumatic stress disorder following the Chernobyl disaster. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:95–102. doi: 10.1017/S109285291200096X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Begić D, Jakovljević M, Mihaljević-Peleš A. Characteristics of electroencephalogram (EEG) in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) combat veterans treated with fluoxetine. Psychiatr. Danub. 2001;13:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jokić-Begić N, Begić D. Quantitative electroencephalogram (qEEG) in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2003;57:351–355. doi: 10.1080/08039480310002688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cottraux J, et al. Enregistrement magnéto-encéphalographique (MEG) de réminiscences du trauma chez des femmes souffrant de stress post-traumatique: Une étude pilote. Encephale. 2015;41:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Casada JH, Amdur R, Larsen R, Liberzon I. Psychophysiologic responsivity in posttraumatic stress disorder: Generalized hyperresponsiveness versus trauma specificity. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;44:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shin LMP, et al. Exaggerated Activation of Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex During Cognitive Interference: A Monozygotic Twin Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:979–985. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.09121812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falconer EM, et al. Developing an IntegratedBrain, Behavior and Biological Response Profile in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (Ptsd). J. Integr. Neurosci. 2008;7:439–456. doi: 10.1142/S0219635208001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber DL. Information Processing Bias in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Open Neuroimag. J. 2008;2:29–51. doi: 10.2174/1874440000802010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blake DD, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J. Trauma. Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Vliet IM, de Beurs E. The MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. A brief structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV en ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 2007;49:393–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delorme A, et al. EEGLAB, MPT, NetSIFT, NFT, BCILAB, and ERICA: New tools for advanced EEG/MEG processing. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011;2011:130714. doi: 10.1155/2011/130714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Platt J, Haykin S. Information-Maximization Approach to Blind Separation and Blind Deconvolution. Technology. 1995;1159:1129–1159. doi: 10.1162/neco.1995.7.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oostenveld, R. et al. FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive ElectrophysiologicalData,. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. e156869, 10.1155/2011/156869 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Neuling T, Rach S, Wagner S, Wolters CH, Herrmann CS. Good vibrations: Oscillatory phase shapes perception. Neuroimage. 2012;63:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;164:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klimesch, Alpha W. rhythms and memory processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1997;26:319–340. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(97)00773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klimesch W, Doppelmayr M, Hanslmayr S. Upper Alpa ERD and Absolute power: their meanıng for memory performance. Progress in Brain Research. 2006;159:151–166. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)59010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klimesch W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999;29:169–195. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vogt F, Klimesch W, Doppelmayr M. High-Frequency Components in the Alpha Band and Memory Performance. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998;15:167–172. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Backer KC, Binns MA, Alain C. Neural Dynamics Underlying Attentional Orienting to Auditory Representations in Short-Term Memory. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:1307–1318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1487-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaiser J, Heidegger T, Wibral M, Altmann CF, Lutzenberger W. Alpha synchronization during auditory spatial short-term memory. Neuroreport. 2007;18:1129–1132. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32821c553b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim S-J, Wostmann M, Obleser J. Selective Attention to Auditory Memory Neurally Enhances Perceptual Precision. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:16094–16104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanslmayr S, et al. The Relationship between Brain Oscillations and BOLD Signal during Memory Formation: A Combined EEG-fMRI Study. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:15674–15680. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3140-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Imperatori C, et al. Aberrant EEG functional connectivity and EEG power spectra in resting state post-traumatic stress disorder: A sLORETA study. Biol. Psychol. 2014;102:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fuentemilla L, Marco-Pallarés J, Münte TF, Grau C. Theta EEG oscillatory activity and auditory change detection. Brain Res. 2008;1220:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ko D, et al. Theta oscillation related to the auditory discrimination process in mismatch negativity: Oddball versus control paradigm. J. Clin. Neurol. 2012;8:35–42. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hsiao F-J, Wu Z-A, Ho L-T, Lin Y-Y. Theta oscillation during auditory change detection: An MEG study. Biol. Psychol. 2009;81:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi JW, Jung KY, Kim CH, Kim KH. Changes in gamma-and theta-band phase synchronization patterns due to the difficulty of auditory oddball task. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;468:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yordanova J, et al. Wavelet entropy analysis of event-related potentials indicates modality-independent theta dominance. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2002;117:99–109. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(02)00095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kirino E. Mismatch negativity correlates with delta and theta EEG power in schizophrenia. Int. J. Neurosci. 2007;117:1257–1279. doi: 10.1080/00207450600936635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaiser J, Lutzenberger W. Induced Gamma-Band Activity and Human Brain Function. Neurosci. 2003;9:475–484. doi: 10.1177/1073858403259137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodionov V, et al. Wavelet analysis of the frontal auditory evoked potentials obtained in the passive oddball paradigm in healthy subjects and schizophrenics. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009;20:233–264. doi: 10.1515/JBCPP.2009.20.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang L, et al. Schizophrenia, culture and neuropsychology: sensory deficits, language impairments and social functioning in Chinese-speaking schizophrenia patients. Psychol. Med. 2012;42:1485–1494. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Campbell T, Winkler I, Kujala T. N1 and the mismatch negativity are spatiotemporally distinct ERP components: Disruption of immediate memory by auditory distraction can be related to N1. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:530–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lanius RA, Frewen PA, Tursich M, Jetly R, McKinnon MC. Restoring large-scale brain networks in ptsd and related disorders: A proposal for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:1–12. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]