Abstract

Objectives

We reviewed testosterone changes for patients who were treated with radiation therapy (RT) alone on NRG oncology RTOG 9408.

Methods and materials

Patients (T1b-T2b, prostate-specific antigen <20 ng/mL) were randomized between RT alone and RT plus 4 months of androgen ablation. Serum testosterone (ST) levels were investigated at enrollment, RT completion, and the first follow-up 3 months after RT. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare pre- and post-treatment ST levels in patients who were randomized to the RT-alone arm.

Results

Of 2028 patients enrolled, 992 patients were randomized to receive RT alone and 917 (92.4%) had baseline ST values available and completed RT. Of these 917 patients, immediate and 3-month post-RT testosterone levels were available for 447 and 373 patients, respectively. Excluding 2 patients who received hormonal therapy off protocol after RT, 447 and 371 patients, respectively, were analyzed. For all patients, the median change in ST values at completion of RT and at 3-month follow-up were −30.0 ng/dL (p5-p95; −270.0 to 162.0; P < .001) and −34.0 ng/dL (p5-p95, −228.0 to 160.0; P < .01), respectively.

Conclusion

RT for prostate cancer was associated with a median 9.2% decline in ST at completion of RT and a median 9.3% decline 3 months after RT. These changes were statistically significant.

Summary.

Patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer who were enrolled in the XXXX trial were randomized to radiation therapy (RT) alone and RT combined with 4 months of total androgen ablation. The current study analyzed whether patients who were treated with RT alone experienced testosterone suppression, presumably due to scatter radiation to the testicular Leydig cells. We found a 9.2% decline in serum testosterone levels at completion of RT and a 9.3% decline 3 months after RT.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Various studies in the contemporary radiation therapy (RT) literature have evaluated changes in serum testosterone (ST) levels for patients receiving external beam RT for prostate cancer1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and other pelvic malignancies.10, 11, 12, 13 The majority of these studies have indicated that these patients experience a decline in ST after RT. Low-dose scatter radiation to the testicular Leydig cells is believed to be the most likely explanation for this phenomenon. The current study evaluates the changes in ST observed in patients who were enrolled and treated in the NRG oncology RTOG 9408 study.

Methods and materials

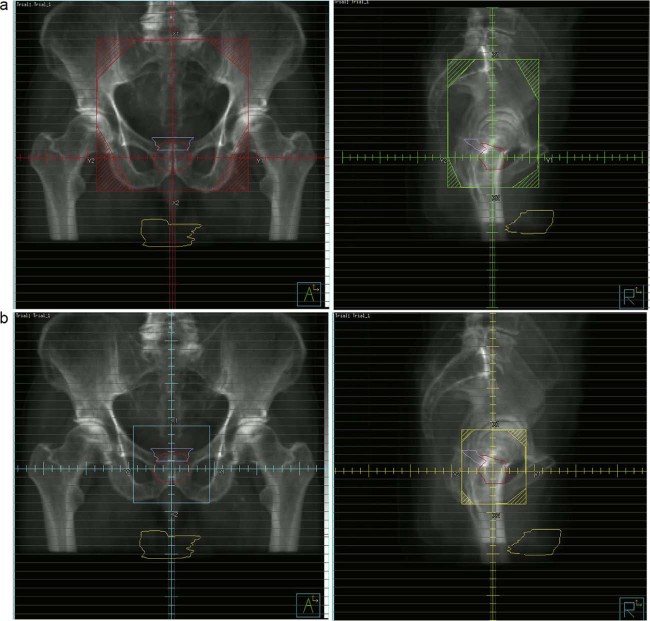

From 1994 through 2001, 1979 eligible patients with stage T1b, T1c, T2a, or T2b prostate adenocarcinoma and a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 20 ng/mL or less were randomly assigned to RT alone or RT with 4 months of total androgen suppression starting 2 months before RT. The primary endpoint for the study was overall survival. The secondary endpoints included disease-specific mortality, distant metastases, biochemical failure (eg, an increasing PSA level), and the rate of positive findings on the planned repeat prostate biopsy at 2 years. The details of the study design and outcomes are well described in a prior publication.14 RT consisted of either whole pelvic RT (WPRT) to 46.8 Gy plus a 19.8 Gy prostate boost for a total dose of 66.6 Gy or RT to the prostate only (PORT) for a total dose of 68.4 Gy. Typical field arrangements are shown in Figure 1a and 1b.

Figure 1.

Regional lymphatics target volumes. Shown are typical whole pelvis (a) and prostate boost (b) fields used to treat patients enrolled on NRG oncology RTOG 9408. The testicles (in yellow) are shown to be well outside of the radiation therapy beam paths.

Most patients received WPRT. Only patients with the lowest-risk features (PSA <10 ng/mL and Gleason score ≤5 or a negative lymph node dissection) were assigned to receive PORT. RT was delivered at 1.8 Gy per fraction. For this analysis, ST levels were investigated at the following collection periods: study enrollment; completion of RT; and first follow-up 3 months after completion of RT. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the change in pre- and post-treatment ST levels (at completion of RT and at the 3-month follow-up visit) in patients who were randomized to the RT-alone arm. The same paired differences were further compared between WPRT and PORT, and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to detect any statistically significant differences. Two different follow-up periods were analyzed: end of RT and first post-RT follow-up. All statistical tests were carried out at the 0.05 significance level. Although it is well recognized that ST levels are subject to diurnal variation, given the large number of patients evaluated, it is unlikely that the results were skewed by any systematic bias as a result of the time of day blood samples were drawn. All laboratory testing was performed at laboratories that were chosen by the institution that enrolled the patient in the study. As such, there was no standardization of the results. Institutional review board approval of the protocol and consent documentation were obtained at each participating institution. All patients signed informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Results

Of the 1979 eligible patients enrolled in the NRG oncology RTOG 9408 study, 992 were randomized to receive RT alone and 925 (93%) had baseline ST values available. Of these 925 patients, 917 (99%) completed RT. Of these 917, 447 had ST information available at the end of RT. None of the 447 patients received hormonal therapy off protocol before the study evaluation. A total of 373 patients had ST values available 3 months after completion of RT. Two of the 373 patients had received hormonal therapy off protocol prior to this evaluation, leaving 371 patients for analysis at that time point. The outliers were included in all analyses. A breakdown of the patients evaluated is shown in Table 1. The pretreatment characteristics of the analyzable patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Availability of serum testosterone levels for patients in the radiation therapy alone arm of NRG oncology RTOG 9408 (n = 992)

| Group | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Total sample | 992 |

| With baseline testosterone | 925 |

| With baseline testosterone and completed RT | 917 |

| With baseline and end of RT testosterone | 447 |

| With baseline and 3-month post-RT testosterone | 371a |

RT, radiation therapy.

Two patients were excluded because of hormone initiation.

Table 2.

Pretreatment characteristics of eligible patients

| WPRT (n = 807) |

PORT (n = 110) |

Total (n = 917) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| Median | 71 | 70 | 71 |

| Range | 47-84 | 51-88 | 47-88 |

| Q1-Q3 | 66-75 | 67-73 | 66-74 |

| Karnofsky performance status | |||

| 70-80 | 56 (6.9%) | 9 (8.2%) | 65 (7.1%) |

| 90-100 | 751 (93.1%) | 101 (91.8%) | 852 (92.9%) |

| Tumor stage | |||

| T1 | 383 (47.5%) | 52 (47.3%) | 435 (47.4%) |

| T2 | 424 (52.5%) | 58 (52.7%) | 482 (52.6%) |

| Node stage | |||

| N0 | 16 (2.0%) | 16 (14.5%) | 32 (3.5%) |

| NX | 791 (98.0%) | 94 (85.5%) | 885 (96.5%) |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well | 96 (11.9%) | 44 (40.0%) | 140 (15.3%) |

| Moderately | 516 (63.9%) | 61 (55.5%) | 577 (62.9%) |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 195 (24.2%) | 5 (4.5%) | 200 (21.8%) |

| Prostate-specific antigen levels | |||

| <4 | 75 (9.3%) | 14 (12.7%) | 89 (9.7%) |

| 4-20 | 732 (90.7%) | 96 (87.3%) | 828 (90.3%) |

| Intercurrent disease | |||

| Absent | 220 (27.3%) | 32 (29.1%) | 252 (27.5%) |

| Present | 585 (72.5%) | 77 (70.0%) | 662 (72.2%) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Gleason score | |||

| 2-6 | 448 (55.5%) | 103 (93.6%) | 551 (60.1%) |

| 7 | 257 (31.8%) | 4 (3.6%) | 261 (28.5%) |

| 8-10 | 77 (9.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | 79 (8.6%) |

| Unknown | 25 (3.1%) | 1 (0.9%) | 26 (2.8%) |

| Testosterone level (ng/dL) | |||

| Median | 370.00 | 352.29 | 367.00 |

| Range | 42.00-1380.40 | 76.00-800.00 | 42.00-1380.40 |

| Q1-Q3 | 280.00-475.00 | 274.00-454.00 | 279.00-466.00 |

PORT, prostate-only radiation therapy; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; WPRT, whole pelvis radiation therapy.

For the entire group of patients who completed RT and had no prior hormonal therapy, the median change in ST was −30.0 ng/dL at the end of RT (P < .001) and −34.0 ng/dL 3 months post-RT (P < .001). The distribution is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Absolute changes in serum testosterone levels

| Baseline to end of RT | Baseline to 3 months post-RT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 447) |

WPRT (n = 386) |

PORT (n = 61) |

All (n = 371) |

WPRT (n = 320) |

PORT (n = 51) |

|

| Minimum | −608.07 | −608.07 | −293.95 | −478.39 | −478.39 | −315.85 |

| 5th percentile | −270.00 | −288.18 | −178.67 | −228.00 | −240.50 | −182.00 |

| Q1 | −109.00 | −110.00 | −57.64 | −99.00 | −100.50 | −86.46 |

| Median | −30.00 | −35.29 | −11.00 | −34.00 | −31.35 | −41.00 |

| Q3 | 38.62 | 40.00 | 29.00 | 32.00 | 41.61 | 15.00 |

| 95th percentile | 162.00 | 172.00 | 125.00 | 160.00 | 169.00 | 65.00 |

| Maximum | 593.66 | 593.66 | 158.50 | 691.00 | 691.00 | 86.46 |

| P-valuea | < .001 | < .001 | .128 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 |

| P-valueb | .216 | .277 | ||||

PORT, prostate-only radiation therapy; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; RT, radiation therapy; WPRT, whole pelvis radiation therapy.

P-value from Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing to 0.

P -value comparing WPRT vs. PORT from Wilcoxon test.

For the subgroup of patients who were treated with WPRT and completed RT and who had no prior hormonal therapy, the median change in ST was −35.3 ng/dL (n = 386) at the end of RT (P < .001) and −31.4 ng/dL (n = 320) 3 months post-RT (P < .001). The distribution is shown in Table 3, and the relative changes are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relative changes in serum testosterone levels

| Baseline to end of RT | Baseline to 3 months post-RT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 447) |

WPRT (n = 386) |

PORT (n = 61) |

All (n = 371) |

WPRT (n = 320) |

PORT (n = 51) |

|

| Minimum | −96.5% | −96.5% | −53.4% | −96.8% | −96.8% | −69.7% |

| 5th percentile | −51.1% | −52.6% | −43.5% | −46.4% | −46.6% | −45.1% |

| Q1 | −27.3% | −27.8% | −14.4% | −25.8% | −26.1% | −24.0% |

| Median | −9.2% | −10.0% | −2.5% | −9.3% | −9.1% | −13.5% |

| Q3 | 12.8% | 13.0% | 12.4% | 9.5% | 13.6% | 4.8% |

| 95th percentile | 59.1% | 59.1% | 53.0% | 53.1% | 57.9% | 22.2% |

| Maximum | 173.1% | 173.1% | 78.6% | 179.2% | 179.2% | 28.6% |

| P-valuea | < .001 | < .001 | .354 | < .001 | .001 | .001 |

| P valueb | .172 | .348 | ||||

Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; PORT, prostate-only radiation therapy; RT, radiation therapy; WPRT, whole-pelvis radiation therapy.

P-value from Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test comparing to 0.

P-value comparing WPRT vs. PORT from Wilcoxon test.

For the subgroup of patients who were treated with PORT and completed RT and who had no prior hormonal therapy, the median change in ST was −11.0 ng/dL (n = 61) at the end of RT (P = .13) and −41.0 ng/dL (n = 51) 3 months post-RT (P < .001). The distribution is shown in Table 3 and the relative changes are shown in Table 4. The difference in the median change in ST between the WRPT and PORT groups was not statistically significant at either the end of RT (P = .216) or 3 months after RT (P = .277).

An effort was made to correlate change in ST with change in sexual function. A total of 337 patients in the RT-alone group completed an initial Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire (SAQ), and 270 patients completed the SAQ 12 months after treatment. However, from the group of patients who completed both SAQs, we identified only 73 patients who also had baseline and 3-month ST data available. This small number of evaluable patients presented problems on 2 levels. First, there was the unlikelihood that our analysis would have the statistical power to correlate ST change with a change in sexual function. Second, because these 73 patients only represented 22% of the 337 patients who answered the initial SAQ, from a missing data analysis perspective, conclusions could be unreliable and misleading. As such, we are unable to offer a meaningful correlation between changes in ST and change in sexual function.

Discussion

The current study represents the second largest series in the RT literature to evaluate changes in ST in patients receiving RT for localized prostate cancer and the largest study based on data collected as part of a large-scale prospective multi-institutional trial. Although a large share of the posttreatment testosterone data were not collected (only 447 patients had ST levels drawn at the end of RT and 371 at 3 months after RT), we believe that this was a function of the decentralized nature of data collection. We do not believe that this introduces systemic bias into the analysis. Although only short-term data were collected, the findings are consistent with most previously published studies that demonstrate a decline in ST after photon-based RT. These studies stand in contrast to recently published studies that fail to demonstrate such testosterone changes after proton-based RT or brachytherapy. Table 5 lists the 7 studies that were published after 1990, alongside the current study.

Table 5.

Literature review

| Literature | No. of patients | Modality | Dose | Serum testosterone change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zagars et al, 19974 | 85 | 2D EBRT | 68 Gy (median) | 9% decline in mean at 3 months |

| Daniell et al, 20013 | 33 | 2D EBRT | 70 Gy (approximate) | 27.3% decline at 3 to 8 years versus prostatectomy patients |

| Pickles et al, 20022 | 666 | 3D CRT | 65 Gy (range, 52.5-70 Gy) | 17% decline in median at 6 months |

| Oermann et al, 20111 | 26 | Robotic Radiosurgery SBRT | 36.25 Gy | 23.7% decline in median at 12 months (P < .013) |

| Nichols et al, 20129 | 150 | Protons | 78-82 Gy (RBE) | No significant change |

| Taira et al, 201215 | 221 | Pd-103 BTx ± EBRT | Not specified | No significant change |

| Kil et al, 20138 | 217 | Protons | 70-72.50 Gy (RBE) | No significant change |

| Current Series | 447 | 2D-EBRT and 3D-CRT | 66.6-68.4 Gy | 9% decline at 3 months |

2D, 2-dimensional; 3D, 3-dimensional; BTx, brachytherapy; CRT, conformal radiation therapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; RBE, relative biological equivalence; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Zagars and Pollack4 reported a 9% decline in ST 3 months after RT in 85 patients treated with RT for prostate cancer. Patients in the series received doses ranging from 66 to 78 Gy (median, 68 Gy) at 2 Gy per fraction to the prostate, only specified at the isocenter. No patient was treated with pelvic nodal RT. The decline in ST was statistically significant at the P = .0001 level.

Daniell et al3 compared the ST levels of 33 men who had undergone RT with those of 55 men who had undergone radical prostatectomy 3 to 8 years after treatment. The irradiated patients had a 27.3% lower ST level compared with the surgically treated patients. The investigators suggested that these findings could be explained by radiation injury to the testicles.

Pickles et al2 reported on 666 men who were treated with RT for localized prostate cancer between 1994 and 2001. No patient received hormonal therapy. According to the investigators, “few” of the patients received pelvic nodal RT. The vast majority was treated with fields that were limited to the prostate. Six months after completion of RT, the mean ST levels had declined to 83% of the baseline pre-RT levels. The authors attribute this decline to scatter radiation dose to the testicles. With further follow-up, the authors noted a normalization of ST in the vast majority of patients.

Oermann et al1 reported on 26 men with low- or intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with stereotactic body RT (SBRT) with robotic radiosurgery. Patients received 36.25 Gy in 5 fractions of 7.25 Gy to the prostate or prostate and proximal seminal vesicles over a 2-week period. The authors observed a 23.7% median decline in ST levels at 1 year, which was significant at the P = .013 level.

One study of testosterone changes after brachytherapy failed to show declines in ST.15 This lack of testosterone suppression was seen in patients treated with brachytherapy alone as well as in patients treated with low-dose external beam RT (20-45 Gy) plus a brachytherapy boost. The authors suggest that the lack of testosterone suppression in this setting is explained by the lower testicular scatter dose associated with brachytherapy.

Grigsby and Perez5 reported on 59 patients with prostate cancer who received 65 to 70 Gy to the prostate. In contrast to subsequently published studies, the authors did not identify significant changes is ST for 24 months after RT. However, significant declines in dihydroxytestosterone as well as increases in follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone were seen.

In contrast to the majority of studies on testosterone kinetics after external photon radiation, 2 recent studies on proton therapy did not demonstrate posttreatment testosterone suppression. Kil et al8 reported on 217 hormone therapy–naive patients with low- or intermediate-risk prostate cancer who received 70.00 (relative biological equivalence [RBE]) to 72.50 Gy (RBE) with hypofractionated passively scattered protons delivered at 2.5 Gy (RBE) per fraction in a prospective study. The median pretreatment ST level was 367.7 ng/dL. There were no significant changes in ST at treatment completion or 6 or 12 months after proton therapy. The authors imply that the lack of testosterone suppression after proton therapy, in contrast to the aforementioned studies of photon-based therapies, is consistent with studies that suggest that passively scattered proton therapy is associated with less out-of-field low-dose scatter radiation than photon-based therapy.16, 17, 18 Nichols et al9 reported on 150 similar patients from the same institution who were treated in an earlier prospective study and received 78.00 (RBE) to 82.00 Gy (RBE) with passively scattered protons delivered at 2.0 Gy (RBE) per fraction. The median pretreatment ST level was 357.9 ng/dL. There were no significant changes in ST at treatment completion or 6, 12, 18, or 24 months after proton therapy.

A number of studies have attempted to estimate or measure the scatter radiation dose to the testicles in the setting of prostate RT. Oermann et al1 estimated a median dose of 2.1 Gy (range, 1.1-5.8 Gy) in the setting of robotic radiosurgery SBRT. The study by King et al19 estimated that testicular scatter doses from intensity modulated RT ranged from 0.84 Gy with PORT to 6.3 Gy in the setting of pelvic intensity modulated RT with a prostate boost. Previous studies used thermoluminescence dosimetry (TLD) measurements to estimate the testicular scatter dose to be in the range of 2 Gy, or approximately 3% of the prescribed dose to the prostate,2, 4, 20, 21 although an earlier TLD study by Grigsby5 estimated a testicular dose of 4.5 to 6.0 Gy.

Leydig cell damage may be age dependent, with older patients experiencing a greater sensitivity to low-dose radiation in the 2 Gy range. Although the aforementioned studies address the effect of low-dose radiation, or lack thereof, in older men who are treated for prostate cancer, 2 earlier studies of higher-dose testicular irradiation in younger men showed no effect on ST. The study by Rowley et al22 involved the irradiation of the testes of 67 male prisoners with an age range of 25 to 52 years. The doses ranged from 0.08 to 6 Gy. The investigators reported that no significant effect was found on the ST levels of the irradiated patients. The study by Shapiro et al23 followed-up 27 men who had undergone RT for soft-tissue sarcomas. They failed to show changes in the ST levels within 30 months of follow-up. The patients in that series had received a wide range of testicular doses, from 0.01 to 25 Gy.

Conclusions

External beam RT as delivered in the NRG Oncology RTOG 9408 study was associated with a median 9.3% decline in ST at 3 months after RT. There was no significant difference in this decline between patients who received WPRT and those who received PORT. These findings are consistent with most other series in the photon RT literature and suggest that low-dose scatter radiation outside of the beam path has a deleterious impact on testicular Leydig cell function.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This project was supported by grants U10CA21661, U10CA180868, and U10CA180822 from the National Cancer Institute and was funded in part by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Department specifically declaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, and conclusions. Publication of this article was funded in part by the University of Florida Open Access Publishing Fund.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Sandler reports receipt of personal fees from Janssen, Medivation, Ferring, AstraZeneca, and Bayer as well as grants from Myriad outside of the submitted work.

References

- 1.Oermann E.K., Suy S., Hanscom H.N. Low incidence of new biochemical and clinical hypogonadism following hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) monotherapy for low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickles T., Graham P., Members of the British Columbia Cancer Agency Prostate Cohort Outcomes Initiative What happens to testosterone after prostate radiation monotherapy and does it matter? J Urol. 2002;167:2448–2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniell H.W., Clark J.C., Pereira S.E. Hypogonadism following prostate-bed radiation therapy for prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:1889–1895. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010515)91:10<1889::aid-cncr1211>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zagars G.K., Pollack A. Serum testosterone levels after external beam radiation for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grigsby P.W., Perez C.A. The effects of external beam radiotherapy on endocrine function in patients with carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1986;135:726–727. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomic R., Bergman B., Damber J.E., Littbrand B., Lofroth P.O. Effects of external radiation therapy for cancer of the prostate on the serum concentrations of testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and prolactin. J Urol. 1983;130:287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seal U.S. FSH and LH elevation after radiation for treatment of cancer of the prostate. Invest Urol. 1979;16:278–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kil W.J., Nichols R.C., Jr, Hoppe B.S. Hypofractionated passively scattered proton radiotherapy for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer is not associated with post-treatment testosterone suppression. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:492–497. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.767983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols R.C., Jr, Morris C.G., Hoppe B.S. Proton radiotherapy for prostate cancer is not associated with post-treatment testosterone suppression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1222–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruheim K., Svartberg J., Carlsen E. Radiotherapy for rectal cancer is associated with reduced serum testosterone and increased FSH and LH. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermann R.M., Henkel K., Christiansen H. Testicular dose and hormonal changes after radiotherapy of rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yau I., Vuong T., Garant A. Risk of hypogonadism from scatter radiation during pelvic radiation in male patients with rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon F.H., Perera F., Fisher B., Stitt L. Alterations in hormone levels after adjuvant chemoradiation in male rectal cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1186–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones C.U., Hunt D., McGowan D.G. Radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:107–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taira A.V., Merrick G.S., Galbreath R.W. Serum testosterone kinetics after brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e33–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesoloras G., Sandison G.A., Stewart R.D., Farr J.B., Hsi W.C. Neutron scattered dose equivalent to a fetus from proton radiotherapy of the mother. Med Phys. 2006;33:2479–2490. doi: 10.1118/1.2207147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin D., Yoon M., Kwak J. Secondary neutron doses for several beam configurations for proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon M., Ahn S.H., Kim J. Radiation-induced cancers from modern radiotherapy techniques: Intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1477–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King C.R., Maxim P.G., Hsu A., Kapp D.S. Incidental testicular irradiation from prostate IMRT: It all adds up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehmer D., Badakhshi H., Kuschke W., Bohsung J., Budach V. Testicular dose in prostate cancer radiotherapy: Impact on impairment of fertility and hormonal function. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amies C.J., Mameghan H., Rose A., Fisher R.J. Testicular doses in definitive radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:839–846. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowley M.J., Leach D.R., Warner G.A., Heller C.G. Effect of graded doses of ionizing radiation on the human testis. Radiat Res. 1974;59:665–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro E., Kinsella T.J., Makuch R.W. Effects of fractionated irradiation of endocrine aspects of testicular function. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:1232–1239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.9.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]