Iron plays a crucial role in biochemistry and is an essential micronutrient for plants and humans alike. Recent progress in the field has led to a better understanding of iron homeostasis in plants, and aided the production of high iron crops for improved human nutrition.

Iron plays a crucial role in biochemistry and is an essential micronutrient for plants and humans alike. Recent progress in the field has led to a better understanding of iron homeostasis in plants, and aided the production of high iron crops for improved human nutrition.

Abstract

Iron plays a crucial role in biochemistry and is an essential micronutrient for plants and humans alike. Although plentiful in the Earth's crust it is not usually found in a form readily accessible for plants to use. They must therefore sense and interact with their environment, and have evolved two different molecular strategies to take up iron in the root. Once inside, iron is complexed with chelators and distributed to sink tissues where it is used predominantly in the production of enzyme cofactors or components of electron transport chains. The processes of iron uptake, distribution and metabolism are overseen by tight regulatory mechanisms, at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level, to avoid iron concentrations building to toxic excess. Iron is also loaded into seeds, where it is stored in vacuoles or in ferritin. This is important for human nutrition as seeds form the edible parts of many crop species. As such, increasing iron in seeds and other tissues is a major goal for biofortification efforts by both traditional breeding and biotechnological approaches.

1. Introduction

The redox properties of iron make it an essential element for practically all life. Iron is a component of cofactors that carry out electron transfer functions, or facilitate chemical transitions such as hydroxylations, radical-mediated rearrangements and (de)hydration reactions. Iron cofactors also function in oxygen transport, oxygen or iron sensing, or regulation of protein stability. The chloroplasts are particularly rich in iron–sulphur (FeS) proteins such as Photosystem I, ferredoxins and a range of metabolic enzymes. Mitochondria are another hotspot for iron enzymes, such as respiratory complexes containing multiple FeS clusters (complex I and II), a mix of FeS and haem (complex III) or haem and copper (complex IV). The peroxisomes and the endoplasmic reticulum contain haem proteins such as peroxidases and cytochrome P450s, whereas mono- and di-iron enzymes are found in all cell compartments.

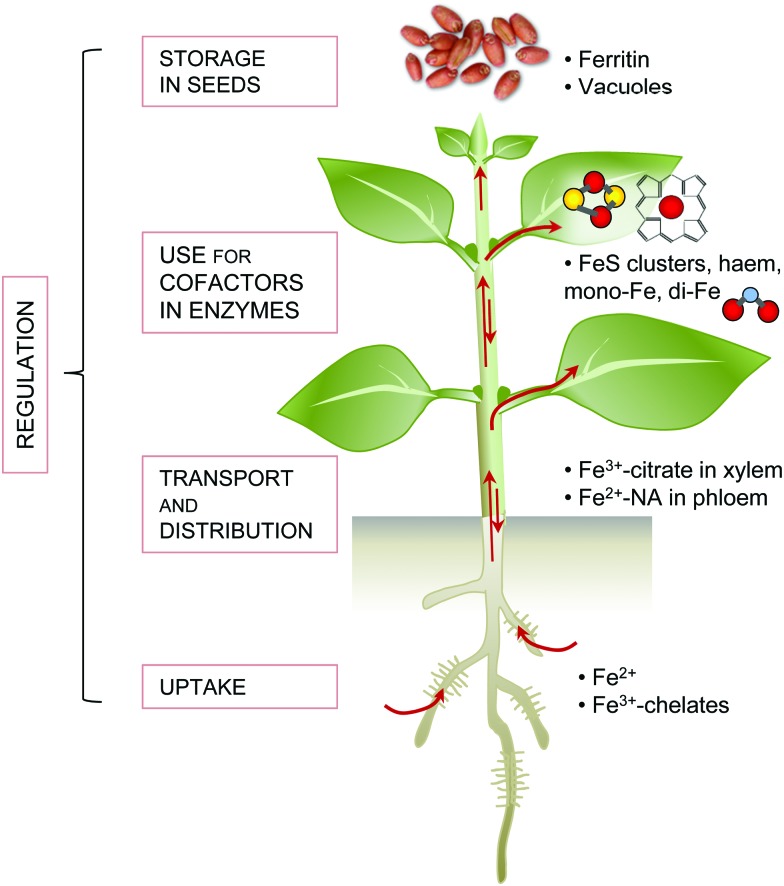

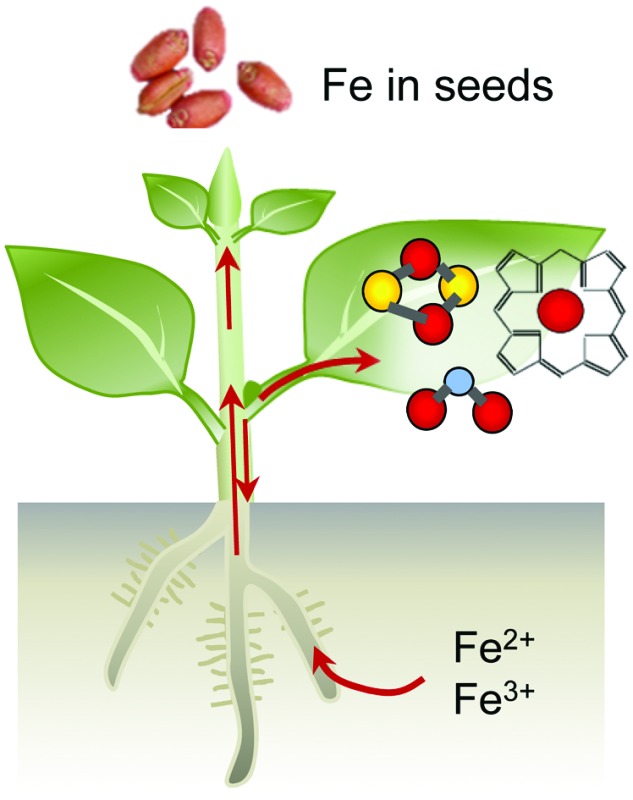

Iron limitation severely affects plant growth and iron is often a component of agricultural fertilisers used to improve crop yields. Although iron is abundant in the Earth's crust, it is usually present in an oxidised form that is not easily accessible for life. Plants, as primary producers, are the gateway for iron to enter the food chain. Iron-deficiency anaemia is a major human health issue, estimated by the World Health Organization to affect over 30% of the world's population (http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ida/en/). On the other hand, excess iron is toxic to cells. Therefore, organisms have evolved intricate mechanisms to take up, metabolise and store iron, and regulate these processes to maintain homeostasis. Fig. 1 gives an overview of the main principles of iron homeostasis in plants. Research over the last decade has identified many key players that deal specifically with iron. These comprise high-affinity uptake transporters and biosynthetic enzymes of organic chelators, transporters for distributing iron to other tissues and storage, enzymes for iron cofactor biosynthesis, plus a regulatory network of transcription factors. Often the finer details of these processes paint a complex picture that can be impenetrable for those new to the field. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of iron homeostasis and how this knowledge can be used to improve human nutrition. We intend it to be an entry-point for those with limited prior knowledge, and hope it may prove useful for teaching purposes. Readers wishing for more detail are referred to the comprehensive review by Kobayashi and Nishizawa (2012),1 or to recent reviews covering specific aspects such as iron uptake and regulation,2 – omics studies applied to Fe deficiency,3 iron mobilisation from soil,4 iron cofactor biosynthesis5 and biofortification.6

Fig. 1. An overview of iron homeostasis in plants. Iron homeostasis is maintained through the action of five processes: high affinity uptake systems, transport and distribution, use in cofactors (metabolism), storage mechanisms and tight regulation of the first four processes. Red balls represent iron ions; yellow balls, sulphide; blue, oxygen.

2. Iron uptake

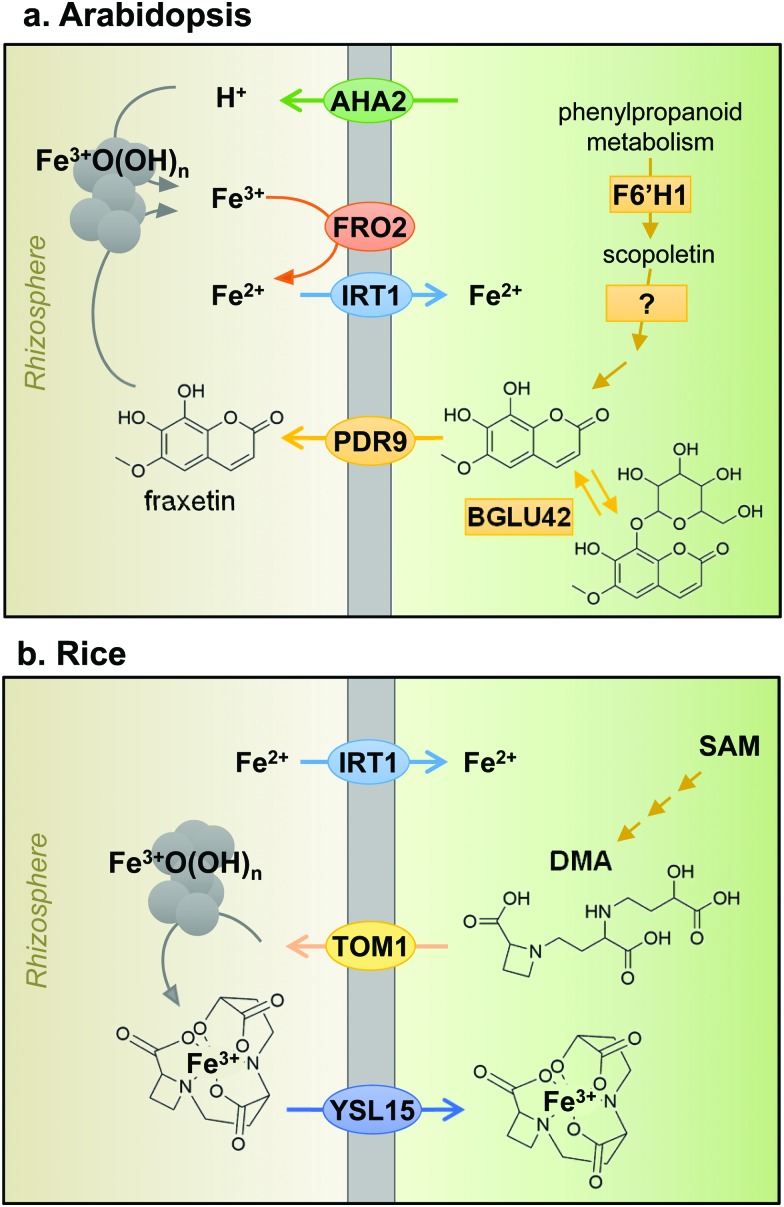

Iron uptake in plants has classically been divided into Strategy I and Strategy II, also known as reducing and chelating strategies, respectively.7 The main difference between both strategies is the oxidation state of iron when taken up by the plant: ferrous Fe2+ for Strategy I and ferric Fe3+ for Strategy II. Iron in the rhizosphere is mainly present as Fe3+ oxyhydrates of low solubility. Tomato and Arabidopsis have served as models for Strategy I (Fig. 2a), in which Fe3+ is reduced by Ferric Reduction Oxidase 2 (FRO2) at the plasma membrane8 before transport across the membrane by Iron-Regulated Transporter 1 (IRT1).9 In addition, plasma-membrane proton pumps such as AHA2 help to acidify the rhizosphere and increase Fe3+ solubility.10 Barley, rice and maize in the grass family (Poaceae) represent Strategy II plants (Fig. 2b), which secrete phytosiderophores, defined as plant-derived small organic molecules with a high affinity for iron.11 Deoxymugineic acid is the most abundant phytosiderophore and is exported by TOM1, the Transporter of Mugineic acid family phytosiderophores, in rice and barley.12 The Fe3+-phytosiderophore chelates are imported by the oligopeptide transporter YS1, first characterised in maize,13 and later in rice (YSL15).14

Fig. 2. Iron uptake mechanisms in plant roots of (a) Arabidopsis, a dicotyledonous plant species and (b) rice, a monocotyledonous plant species. See text for more information on individual components. AHA2, H+-ATPase 2; FRO2, Ferric Reduction Oxidase 2; IRT1, Iron-Regulated Transporter 1; F6′H1, Feruloyl CoA ortho-hydroxylase 1; BGLU42, beta-glucosidase 42; PDR9 or ABCG37, ABC transporter G family member 37; TOM1, Transporter of Mugineic acid family phytosiderophores; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; DMA, 2-deoxy-mugineic acid; YSL15, Yellow Stripe-Like 15.

However, the dichotomy of iron uptake into Strategy I and Strategy II plants is perhaps too simplistic when considering recent discoveries in the iron-deficiency response. Strategy I plants were found to export an array of metabolites including organic acids, phenolics, flavonoids and flavins.15 Phenolics were initially hypothesised to help with the solubilisation and reutilisation of apoplastic iron in red clover.16 This feature was not considered part of the iron uptake mechanism until coumarin-derived phenolics were observed in Arabidopsis under high pH conditions.17–19 Coumarins are synthesised using precursors from the phenylpropanoid pathway. The first coumarin in the pathway, scopoletin, is synthesised by the enzyme feruloyl CoA ortho-hydroxylase 1 (F6′H1).17,19,20 While there is some uncertainty about the next intermediate(s) and the precise biosynthetic steps, the active end product is most likely fraxetin.21 An important chemical feature of fraxetin for iron chelation and mobilization is the catechol moiety, two adjacent hydroxyl groups on a benzene ring (Fig. 2a).19,21 The secretion of coumarin chelators is dependent on specific β-glucosidases to remove a glucoside group, such as BGLU42,22 and the ATP-binding cassette transporter PDR9/ABCG37.17,18 Other plant species such as alfalfa (Medicago) and sugar beet secrete flavins instead of coumarins, which also function to facilitate the reduction of ferric iron.17,23 In addition, secretion of the polyamine compound putrescine appears to improve mobilisation of iron inside the plant cell wall.24 Taken together, the results imply that Strategy I plants produce and secrete chelators to the rhizosphere, a characteristic of Strategy II plants. Having said that, mutant studies showed that to take up iron mobilised by coumarins, FRO2 and IRT1 are required, thus IRT1 remains the main route of iron uptake in Arabidopsis.25 Moreover, rice and barley have a functional homologue of IRT1, which mediates the uptake of Fe2+ under low oxygen,26,27 thus blurring the distinction between Strategy I and II even further. Two different uptake strategies for Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the same organism are widespread in Nature. For example, in animals, Fe2+ is transported by the Divalent Metal Transporter DMT1 and Fe3+ is captured by transferrin by the same cells.28 Bacteria take up both Fe2+ and Fe3+-chelates by specific transporters.29

3. Iron distribution and storage

Most iron enters the plant via the root and then needs to be transported to the sink tissues where it is required for iron-dependent enzymes. IRT1 is predominantly localised to the outward facing membrane of epidermal cells30 suggesting that is where iron first enters the symplastic pathway in which cells are connected by plasmodesmata. It is likely that efflux transporters localise to the inner membrane domain of root epidermal cells, but these have not yet been identified.31 NRAMP1 is suggested to cooperate with IRT1 in iron uptake, possible as a low-affinity uptake system.32 Nutrients can also travel through the apoplastic space formed by the cell walls of epidermis and cortex cells to reach the endodermis. Here iron meets a barrier in the form of the Casparian strip, a layer of waterproof lignin, which forces all iron to pass into the symplast. The endodermis can therefore be considered a checkpoint for the translocation of iron into the plant.33 The amount of suberisation of the endodermis changes in response to environmental factors, with iron-deficient plants showing a marked decrease in suberisation that results in an increase in the permeability of the endodermis, allowing more iron to enter the vasculature.34

Due to its toxicity and low solubility iron must be complexed to chelators to be translocated effectively without causing damaging redox reactions. In the symplast iron is thought to be transported in the form of Fe2+–nicotianamine (NA) complexes. NA is a non-protein amino acid produced from S-adenosyl methionine by nicotianamine synthase (NAS), encoded by a small gene family in most plant species.35–37 NA is a precursor of mugineic acid (see Section 2) and it also chelates Zn2+ and other divalent cations. Once iron has passed the endodermis, it can be loaded into the xylem for transport to the shoot. This is carried out by the pericycle, a layer of cells inside the endodermis. The xylem comprises dead cells that form a conduit, therefore iron needs to be exported from the symplastic space into the apoplast, possibly by YSL238 and ferroportin,39 although biochemical evidence from transport studies is currently lacking. The dominant form of iron in the xylem is Fe3+–citrate40 and consequently Fe2+ must be oxidised to Fe3+. In addition, citrate efflux is crucial for iron translocation, and this is mediated by the efflux transporter FRD3 in Arabidopsis41 and its orthologue FRDL1 in rice.42

An important sink tissue for iron is the leaves, where it is needed for photosynthesis. Here iron re-enters the symplast and is reduced to Fe2+, mainly by the action of FRO proteins, and is again found as Fe2+–NA. A large proportion of iron is used in the plastids and mitochondria and iron transporters specific for each type of organelle have been identified, see recent reviews.43,44 Iron is remobilised from leaf tissues and reaches other sink organs through the phloem. In Arabidopsis the oligopeptide transporter family protein OPT3 is involved in this process and opt3 mutants have more iron trapped in leaves with less translocated elsewhere such as the seed.45,46

Though present in many tissues, the terminal destination of iron is often considered to be the seed, where iron stores are important during germination before the seedling has developed a root and takes up nutrients from the soil. YSL transporters are involved in seed loading,47 and there is evidence that iron can be delivered to pea embryos as a Fe3+-citrate/malate complex.48

Two major storage mechanisms for iron are proposed: sequestration into vacuoles and into ferritin. The Vacuolar Iron Transporter VIT1 was first identified in Arabidopsis as an orthologue of the yeast iron transporter CCC1. In vit1 mutants, the iron content of embryos is similar to wild type, but the iron no longer accumulates in the vacuoles of the root endodermis and veins.49,50 The action of the efflux transporters NRAMP3 and NRAMP4 releases iron into the cytosol during germination.51 A suppressor screen of nramp3/nramp4 mutants identified mutations in VIT1 that rescue their sensitivity to low iron.52 Genes from the VIT family are also known to be important for iron localisation in rice grains and Brassica seeds.53,54

Ferritins are important iron storage proteins present across the biological kingdoms. Twenty-four subunits form a shell able to store up to a maximum of 4500 Fe3+ ions, although purified plant ferritin, for example from legume seeds, tends to contain approximately 2500 ions.55 The proportion of total iron stored in ferritin in seeds varies among species, with approximately 60% in peas but less than 5% in Arabidopsis seeds.56 In plants, ferritin is predominantly located in the plastids. In cereal grains such as wheat and rice, most iron is present in vacuoles in the aleurone layer which is often removed during grain processing.57 The way in which iron is stored in seeds can affect its bioavailability when consumed, which is of great importance to biofortification studies (see Section 6).

4. Biosynthesis of iron co-factors

The most common forms of iron cofactors are haem, FeS clusters and di-iron centres.5,58 Haem contains one iron atom inserted into an organic tetrapyrrole ring and is non-covalently or covalently (in the case of c-type cytochromes) bound to the protein. In FeS clusters, 2 or 4 iron atoms are bridged by acid-labile sulphides and linked to at least one cysteine sulphur of the protein. The ligands of the iron atom are critical in modifying the precise catalytic properties of an enzyme. For example, all-cysteine FeS clusters occupy the lower range of redox potentials (approximately –300 to +100 mV) and haems the higher range (+50 to +400 mV).58 Di-iron centres, also known as Fe–O–Fe centres, and mono-iron centres are generally bound by histidine, glutamate and aspartate residues and function in hydroxylation and oxygenation reactions, respectively.

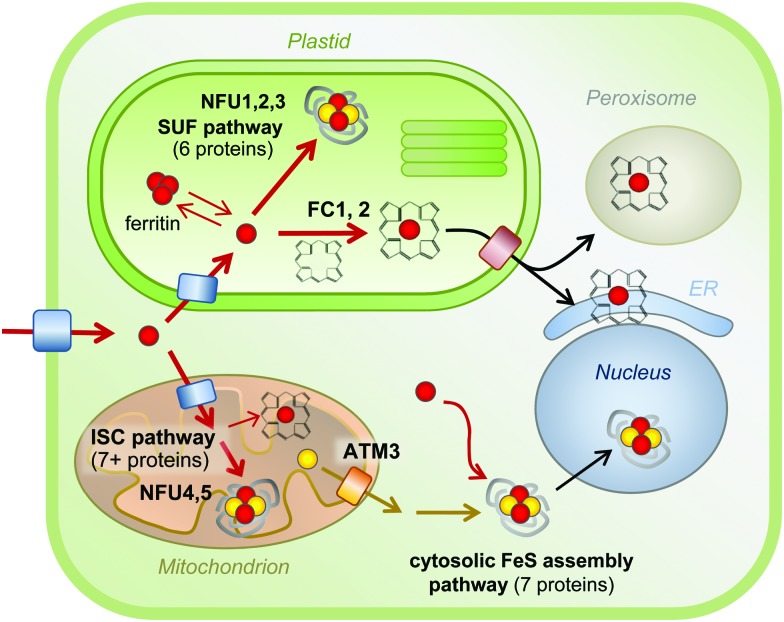

Because of the toxic nature of free iron, cofactor biosynthesis is a highly controlled process. The biosynthesis pathways of haem and FeS clusters are well characterised (Fig. 3), but little is known about the delivery of iron to these pathways or to mono- and di-iron enzymes. Plants contain relatively little haem in comparison to animals, about 0.5–1% of total iron.59 Haem biosynthesis takes place in the plastids, as a branch of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Both molecules have a tetrapyrrole ring but a different metal (Fe and Mg, respectively) and specific side groups. The starting point for the biosynthesis of tetrapyrrole is glutamate in the form of glutamyl-tRNAGLU, and the pathway involves nine enzymes essentially conserved with bacteria, before insertion of iron by ferrochelatase (FC).60 Land plants express at least two isoforms of FC. Mutant studies in Arabidopsis have shown that FC1 provides haem at all growth stages, whereas FC2 boosts haem levels in chloroplasts during photosynthesis.59,61 Haem is presumably transported from its site of biosynthesis to other cell compartments, but the transporters have not been characterised in plants. In fungi and metazoa, mitochondria are the site of haem biosynthesis, and it has been proposed that plant mitochondria harbour enzyme isoforms for the last two steps, although firm evidence is lacking.

Fig. 3. Iron cofactor assembly pathways in Arabidopsis. Overview of the biosynthesis pathways for FeS clusters and haem and their localisation in a typical plant cell. Iron is represented by red spheres, sulphur by yellow spheres. Please note that the concentration of ‘free’ iron or ‘free’ sulphur in cells is close to zero, as these elements will be chelated or form part of a larger molecule to avoid toxicity. Similarly, FeS clusters do not exist in free form, and are only stable within a protein fold. Mono-iron and di-iron cofactors are not depicted, but occur in all cell compartments. See the main text for more details. ATM3, ABC Transporter of the Mitochondria 3; ER, Endoplasmic reticulum; FC, Ferrochelatase; ISC, Iron-Sulphur Cluster; NFU, NifU-like protein; SUF, Sulfur mobilization.

For the biosynthesis of FeS clusters, both plastids and mitochondria harbour complete assembly pathways (see reviews5,62). Cysteine serves as the source of acid-labile sulphur, which is transferred from the active site of the desulphurase enzyme to a scaffold protein where sulphide is combined with iron. The precise mechanistic details of the assembly process remain to be established, but it does require reducing equivalents provided by ferredoxin and/or NADPH.63,64 The plastid and mitochondrial cysteine desulphurases belong to different pathways, called SUF (SUlFur mobilization) and ISC (Iron Sulfur Cluster), respectively. The genes are mostly conserved with those in bacteria. The plastid pathway consists of 6 SUF proteins, all except SUFA essential for plant viability. SUFS and SUFE form the desulphurase activity65 and the SUFB2CD complex is the FeS cluster scaffold.66 SUFA and 3 partially redundant NFU proteins are involved in carrying FeS clusters from the scaffold to recipient FeS proteins. In the mitochondrial ISC pathway, a similar division in desulphurase activity (NFS1 and ISD11), scaffold (ISU) and carrier proteins (NFU4 and NFU5) can be made. FeS clusters cannot cross membranes – except as part of folded proteins through the twin-arginine pathway – and a separate set of at least 7 proteins for Cytosolic Iron–sulphur protein Assembly (CIA) are required for the activity of FeS enzymes in the cytosol and nucleus.67 The CIA pathway is functionally connected to the mitochondria, which are thought to provide sulphur exported by an ATP Binding Cassette transporter.68,69 Interestingly, forward and reverse genetics studies have highlighted the importance of Arabidopsis CIA proteins in plant development, because of the role of FeS enzymes in plant hormone biosynthesis, DNA demethylation and DNA repair.70–74

5. Regulation of iron homeostasis

An efficient regulatory system that senses the iron status of the plant, and adjusts homeostasis accordingly, is crucial for ensuring enough iron reaches the tissues where it is needed without accumulating to toxic levels. Plants adapt their root morphology to iron-limiting conditions by increasing the density of root hairs and the number of lateral roots. The greater surface area extends contact between the epidermis and the rhizosphere, and the lateral roots help to explore fresh soil.75 These macroscopic changes have been studied mostly from the perspective of plant development.76 The entry of iron into the symplast is controlled at the endodermis (see Section 3). The precise molecular mechanisms that link iron availability to changes in root morphology or permeability are not yet known.

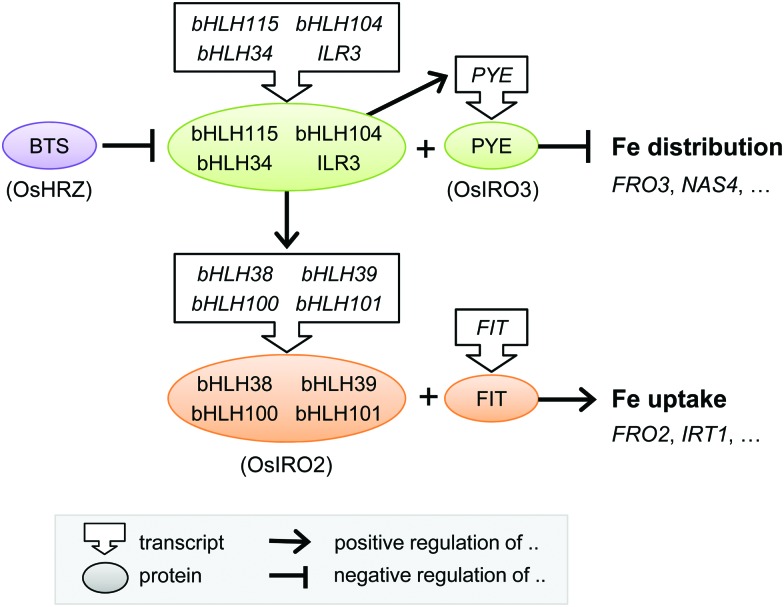

Over the past 15 years, great progress has been made in identifying a large number of transcriptional regulators of iron homeostasis. However, this has led to a somewhat bewildering network of basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factors that regulate the iron deficiency response (see Table 1 and Fig. 4). The first transcription factor that was cloned was FER from tomato,77 followed shortly by its functional orthologue in Arabidopsis called FER-like Iron deficiency-induced Transcription factor (FIT). FIT is expressed in roots only and required for up-regulating iron uptake genes such as FRO2 and IRT1.78–80 FIT cannot act alone but must form a heterodimer with one of four other bHLH proteins, bHLH38, bHLH39, bHLH100 and bHLH101, to bind to the promoters of IRT1 and FRO2, as was elegantly shown in yeast.81,82 Mutant studies in Arabidopsis have shown that the four partner proteins are partially redundant,82 but they may fine-tune the response by activating different downstream genes.83

Table 1. Transcription factors involved in iron homeostasis.

| Gene | Expression pattern | Downstream genes | Ref. |

| FIT1 | Root | Direct: FRO2, IRT1 | 78–81 |

| Other: MYB10, MYB72, F6'H1, many other genes | |||

| Subgroup Ib: | |||

| bHLH38, bHLH39 | All tissues | FRO2, IRT1, | 81–83 |

| bHLH100, bHLH101 | Phenylalanine metabolism | ||

| Subgroup IVc: | |||

| bHLH034 | Vasculature | bHLH38/39/100/101, PYE | 85 and 86 |

| bHLH104 | Vasculature | ||

| bHLH105 (ILR3), bHLH115 | Vasculature, meristems | ||

| MYB10 | Roots | NAS4 | 22 and 87 |

| MYB72 | Coumarin biosynthesis, BGLU42 | ||

| WRKY46 | Roots | Direct: VITL1 | 88 |

| NAS2? | |||

| PYE | Roots and shoots | Direct: NAS4, ZIF1, FRO3 | 84 |

| IDEF1 a | Roots (phloem) and leaves (mesophyll) | Phytosiderophore biosynthesis, OsIRT1, OsIRO2 | 92 and 123 |

| IDEF2 a | Roots and leaves (vasculature) | YSL2 | 92 and 124 |

| IRO2 a | Roots and shoots | Phytosiderophore biosynthesis, YSL15 | 91 |

| IRO3 a | Roots and shoots | NAS1, NAS2, IRO2 | 93 |

aRice genes. The closest homologue of IRO2 is bHLH39 in Arabidopsis. For IRO3, the closest homologue is PYE. There are no homologues of IDEF1 and IDEF2 in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 4. Transcriptional regulation of the iron deficiency response in plants. Diagram depicting the core transcriptional regulators and their functional relationship. The rice homologues are given in parentheses, but note that downstream gene targets in rice may differ. Further details can be found in the main text and in Table 1. bHLH, basic Helix-Loop-Helix protein; BTS, BRUTUS; FIT, FER-like Iron deficiency-induced Transcription factor; PYE, POPEYE.

A cell-type specific microarray study of iron-deficient Arabidopsis roots identified another bHLH protein POPEYE (PYE) which is part of a regulatory network independent of FIT.84 PYE interacts with two bHLH transcription factors, ILR3 (bHLH105) and bHLH115, and is itself regulated by dimers of ILR3 and bHLH104, or ILR3 and bHLH34.85,86 Other families of transcription factors have also been implicated in the iron deficiency response. MYB10 and MYB72 of the MYB family regulate expression of NAS487 and the production of coumarins.22 Recently, a member of the WRKY family, WRKY46, was demonstrated to regulate expression of NAS2 and the VIT-Like 1 gene.88

There is less information about the transcriptional networks governing iron uptake in monocotyledonous plants. Studies have focused on finding transcription factors that bind to the iron-responsive motifs in the promoter of Iron Deficiency Specific clone 2 (IDS2).89 This strategy led to the discovery of transcription factors IDEF1 and IDEF2 in rice,90 which control the expression of phytosiderophore biosynthesis and YSL2.92 Part of the transcriptional regulatory networks found in Arabidopsis, including members of the bHLH transcription family, are conserved in rice. IRO2 in rice is a close homologue of bHLH39 and positively regulates phytosiderophore biosynthesis and YSL15.91 IRO3 is the rice orthologue of PYE and negatively controls the transcript levels of IRO2 and NAS.93

The iron-deficiency response results in an increase in iron uptake which could inadvertently lead to overload if iron becomes suddenly available in the environment, such as after rainfall. Several post-transcriptional mechanisms have been observed that rapidly stop iron uptake. For example, IRT1 is continuously recycled from the plasma membrane via ubiquination and internalisation, and an E3 ligase responsible for its ubiquination has been identified.94 In addition to swiftly degrading the uptake machinery, it is also necessary to stop the transcriptional response. FIT has been reported to be actively turned over in response to ethylene and nitric oxide,83,95,96 but no E3 ligase responsible for FIT degradation has been found to date. Ultimately, all these mechanisms must relate to the iron status in the cell, assuming the existence of Fe-binding regulators such as Fur in bacteria, Aft1 in yeast, or IRPs and FBXL5 in mammals. Recent studies in plants suggest that a small family of hemerythrin E3 ligases, including BRUTUS (BTS) in Arabidopsis97 and HRZ in rice,98 may sense iron and act as negative regulators of the iron deficiency response. The three hemerythrin domains in the N-terminus of BTS and HRZ have conserved His-xxx-Glu motifs likely to bind a di-iron centre. The C-terminal domain has 45% homology to plant and mammalian E3 ligases that target transcription factors for ubiquitination and subsequent turnover. Interestingly, BTS was found to interact with selected bHLH proteins,97 but many questions remain. Such as how the hemerythrin domains sense intracellular Fe levels, why there are three hemerythrin domains, and how iron binding modulates the E3 ligase activity of the C-terminal domain.

6. Biofortification of crops with iron

As our understanding of the mechanisms of iron uptake, transport and homeostasis increase, more applications of this knowledge are being explored to biofortify crops. The five most widely-consumed crops in the developing world are maize, rice, wheat, pulses and cassava (www.fao.org/in-action/inpho/crop-compendium/en/), and as such biofortification efforts have focussed on these species. As mentioned previously, plants exhibit tight homeostatic control to prevent accumulation of iron where it is not needed, and this may limit iron redistribution to edible tissues such as seeds. Any successful biofortification strategy must bypass these mechanisms without causing physiological damage to the plant. Progress is being made through two main strategies: traditional breeding and modern technology including transgenics (Table 2).

Table 2. Selected examples of successful iron biofortification strategies in crops.

| Crop | Details | Strategy employed | Fe content (fold increase over control) | Ref. |

| Beans | High iron landrace | Traditional breeding for high iron content – molecular details unknown | 1.7× in whole beans | 102 and 105 |

| Cassava | AtVIT1 with PATATIN promoter | Transgenic: increased iron storage in target tissue | 3–4× in storage roots | 107 |

| Rice | Combination of overexpressing AtNAS1, OsNAS2, GmFERRITIN and AfPHYTASE | Transgenic: increased iron translocation and storage, degradation of phytate | 6× in T4 polished seeds | 125 |

| Wheat | OsNAS2 with ZmUBIQUITIN promoter | Transgenic: increased translocation. Co-transformation with ferritin had no synergistic effect | 2.5× in whole grains | 126 |

Traditional breeding methods have existed for thousands of years and given rise to many useful crop varieties. However, breeders have concentrated primarily on increasing yield, and as a consequence the levels of iron have been diluted by increased starch.99 One current drive in crop research is to restore old traits in modern varieties to make them more nutritious. For example, the NAM-B1 transcription factor has been lost from modern wheat but is present in older varieties where it advances senescence and leads to higher iron, zinc and protein content in the grain,100 a discovery which has since informed breeding programmes.101 In a separate approach, taking advantage of natural variation has made it possible to breed for higher iron levels in crops such as beans and pearl millet.102,103 In pilot studies, in part funded by HarvestPlus (; http://www.harvestplus.org), high iron varieties of these crops have been used successfully to improve iron status in iron-deficient and anaemic women and children in Rwanda and India.103–105

Alternative approaches for iron biofortification use transgenic and cisgenic technologies. The advantage of these practices over traditional breeding is that it is possible to target genes of interest directly, altering expression of endogenous genes (cisgenics) or introducing genetic material from other species (transgenics). Such approaches have successfully biofortified rice by constitutively expressing endogenous NAS genes,106 and cassava by expressing Arabidopsis VIT1 in storage roots.107 Iron storage in both ferritin and vacuoles have been targeted by cisgenic strategies to biofortify wheat grain.108,109 Increasing VIT expression in the wheat endosperm redirects iron to this part of the grain (Fig. 5). A concern about using transgenics in biofortification is that, mainly due to low substrate specificity of the IRT1 transporter, levels of toxic metals such as cadmium may increase alongside iron.110 This has so far not been a problem, for example overexpression of barley Yellow Stripe 1 (HvYS1) led specifically to increases in iron.111

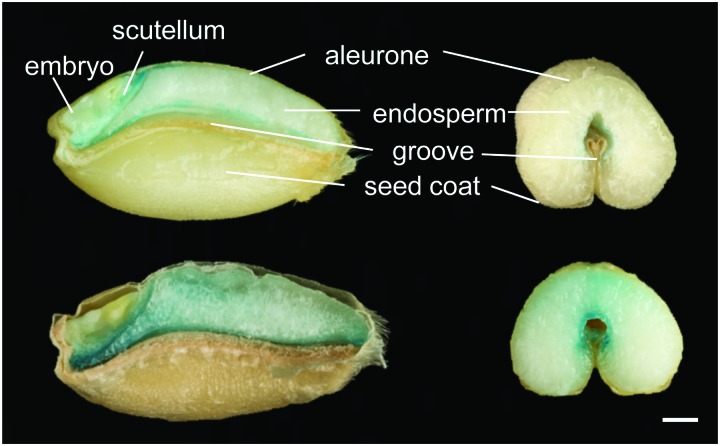

Fig. 5. Perls’ Prussian Blue staining for iron in wheat grains from control line (top) and high-iron line expressing TaVIT2 in the endosperm (bottom). Grains were dissected longitudinally (left) or transversely (right) using a platinum-coated blade. For further details see Connorton et al., 2017.109 Scale bar = 1 mm.

One limitation is that only relatively few crop varieties can be transformed using current techniques, and so traits developed in “transformable” varieties must be introduced into elite varieties by potentially time-consuming crosses. Modern genetic technologies such as TILLING and CRISPR/Cas are not classed as transgenic, and could prove valuable in producing iron biofortified crops. TILLING populations have been produced in species such as wheat, which allow researchers to knock out the function of specific genes.112 As well as being a useful tool for studying gene function, this also unlocks the potential to suppress the function of negative regulators of iron accumulation in specific tissues.

A further obstacle when biofortifying cereals is that iron and other minerals are often poorly bioavailable. The main reason for this is the presence of anti-nutrient compounds such as phytate (myo-inositol-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate) and polyphenols which chelate minerals and prevent them being absorbed by the gut.113 Phytate is a phosphate storage compound abundant in the aleurone and seed coat of cereal grains. Several strategies have been explored to decrease the level of phytate in crops, such as breeding programs aided by identification of relevant Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL)114 and expression of phytase genes.115 Recently published research into phosphate transport showed that rice mutants lacking the SPDT phosphate transporter had a sharp decrease in grain phytate levels as well as a modest increase in iron and other minerals.116 It should also be noted that the way plant material is processed post-harvest can affect bioavailability: iron in white flour is generally more bioavailable than wholemeal flour,117 sourdough bread is produced with bacteria that have naturally occurring phytases,118 and the micromilling of flour can aid bioavailability of minerals.119 Future biofortification strategies would take account of all these factors, combining high iron in edible parts along with low phytate, and using post-harvest processes that increase bioavailability. Current research efforts tend to focus on one of these factors at a time, although more combinatorial studies are emerging (Table 2).

7. Conclusions and future perspectives

Great progress has been made over the past decade in understanding the mechanisms of iron homeostasis in plants. More studies are emerging where information gathered in model plants is being used to study crops, and to generate varieties with higher levels of iron. Many topics do remain to be addressed, however, which will influence future research directions. For example, the substrate specificities of the many transporters involved in iron transport – from cell-to-cell and between intracellular compartments – need to be demonstrated by biochemical studies. Long-distance signalling between shoots and roots has not been discussed in this review, because the components are unknown. The transcriptional networks involved in iron homeostasis have rapidly expanded, but many redundancies between gene functions have been reported and a unified model of the signalling cascade is lacking. cis-Element prediction tools have recently been refined,120–122 but approaches such as ChIP-seq analysis would more clearly define transcriptional regulons and help establish the hierarchy of the different transcription factors. In addition, a tissue- or cell-specific view of iron homeostasis would be insightful, and the function of the cell wall is usually overlooked. A major unresolved question is how iron in plants is sensed, what the precise role of the BTS/HRZ proteins is, and how the iron status is signalled to permeability changes of the endodermis. There is also still limited information available on how the speciation of iron impacts on the bioavailability of iron in plant foods. Overall, these are exciting times, with traditional physiological and genetic studies of iron homeostasis being enhanced by genomics and metabolomics approaches.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for funding from HarvestPlus (J. M. C.) and the BBSRC BB/N001079/1, BB/J004561/1. J. R.-C. was funded by a Marie Sklodowska Curie fellowship from the EU H2020 programme.

Biographies

From left to right: James M. Connorton, Janneke Balk and Jorge Rodríguez-Celma

Dr James Connorton studied Biochemistry at the University of Sheffield (UK) then completed a PhD in Plant Science at the University of Manchester (UK) investigating the function of plant calcium transporters. He then went on to work at the CEA in Grenoble (France). Since 2013 he is a post-doctoral researcher at the John Innes Centre in Norwich (UK) working on iron transport in crop plants and improving the mineral content of wheat grain.

Dr Janneke Balk studied Biology at Wageningen University (Netherlands) followed by a DPhil in Biological Sciences at the University of Oxford (UK). In 2005 she received a Royal Society University Research Fellowship to set up her own group at the University of Cambridge and study iron–sulphur cluster assembly in plants. She is currently a Project Leader at the John Innes Centre in Norwich and an Associate Professor at the University of East Anglia. Her research interests are mitochondria, iron–sulphur proteins and iron homeostasis.

Dr Jorge Rodríguez-Celma studied Biochemistry at the University of Zaragoza (Spain), where he also completed his PhD, which was on proteomics applied to iron deficiency and cadmium toxicity in plants. He moved to the Academia Sinica in Taipei (Taiwan) to do post-doctoral research on iron and manganese-regulated transcription networks. In 2015 he received a Marie Sklodowska Curie Individual Fellowship to study Fe sensing mechanisms in plants at the University of East Anglia and John Innes Centre (UK).

References

- Kobayashi T., Nishizawa N. K. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012;63:131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbarova T., Bauer P., Ivanov R. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Lan P. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:40. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. H., Schmidt W. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:538–548. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balk J., Schaedler T. A. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014;65:125–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos M. W., Gruissem W., Bhullar N. K. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017;44:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römheld V., Marschner H. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:175–180. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N. J., Procter C. M., Connolly E. L., Guerinot M. L. Nature. 1999;397:694–697. doi: 10.1038/17800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide D., Broderius M., Fett J., Guerinot M. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:5624–5628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi S., Schmidt W. New Phytol. 2009;183:1072–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi K. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:471–480. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozoye T. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:5446–5454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C. Nature. 2001;409:346–349. doi: 10.1038/35053080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3470–3479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesco S., Neumann G., Tomasi N., Pinton R., Weisskopf L. Plant Soil. 2010;329:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. W. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:278–285. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.095794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Celma J. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1473–1485. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourcroy P. New Phytol. 2014;201:155–167. doi: 10.1111/nph.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid N. B. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:160–172. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.228544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai K. Plant J. 2008;55:989–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisó-Terraza P. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1711. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamioudis C., Hanson J., Pieterse C. M. J. J. Physiol. 2014;204:368–379. doi: 10.1111/nph.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisó-Terraza P., Rios J. J., Abadía J., Abadía A., Álvarez-Fernández A. New Phytol. 2016;209:733–745. doi: 10.1111/nph.13633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. F., Wang B., Song W. F., Zheng S. J., Shen R. F. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:558–567. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourcroy P., Tissot N., Gaymard F., Briat J. F., Dubos C. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y. Plant J. 2006;45:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedas P. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:455–466. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. J. R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2015;1853:1130–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer L. D., Skaar E. P. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016;50:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberon M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8293–8298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402262111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubeaux G., Zelazny E., Vert G. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2015;8:e1038441. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2015.1038441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaings L. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37222. doi: 10.1038/srep37222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberon M. New Phytol. 2017;213:1604–1610. doi: 10.1111/nph.14140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberon M. Cell. 2016;164:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H. Plant J. 2003;36:366–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatte M. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:257–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau J., Baumann U., Beasley J., Li Y., Johnson A. A. T. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:2228–2239. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato R. J., Roberts L. A., Sanderson T., Eisley R. B., Walker E. L. Plant J. 2004;39:403–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3326–3338. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellán-Alvarez R. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:91–102. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. S., Rogers E. E. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2523–2531. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ma J. F. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:5485–5494. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finazzi G. Cell Calcium. 2015;58:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K., Rasheed S., Kobayashi T., Seki M., Nishizawa N. K. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1192. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2249–2264. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cózatl D. G. Mol. Plant. 2014;7:1455–1469. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jean M., Schikora A., Mari S., Briat J.-F., Curie C. Plant J. 2005;44:769–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillet L. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:2515–2525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. A. Science. 2006;314:1295–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.1132563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roschzttardtz H., Conéjéro G., Curie C., Mari S. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1329–1338. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.144444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V. EMBO J. 2005;24:4041–4051. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary V. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:748–759. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xu Y.-H., Yi H.-Y., Gong J.-M. Plant J. 2012;72:400–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1353. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theil E. C. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska-Dawidziak M. Nutrients. 2015;7:1184–1201. doi: 10.3390/nu7021184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou B. J. Cereal Sci. 2014;59:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fraústo da Silva J. J. R. and Williams R. J. P., The biological chemistry of the elements: The inorganic chemistry of life, Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Espinas N. A. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1326. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezowski P., Richter A. S., Grimm B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1847:968–985. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfenberg M. Plant, Cell Environ. 2015;38:280–298. doi: 10.1111/pce.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J., Touraine B., Briat J.-F., Gaymard F., Rouhier N. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:259. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciocchi A., Douce R., Alban C. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24966–24975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Mitsui A., Fujita Y., Matsubara H. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:104–110. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoewyk D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:5686–5691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Kato Y., Sumida A., Tanaka A., Tanaka R. Plant J. 2017;90:235–248. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netz D. J. A., Mascarenhas J., Stehling O., Pierik A. J., Lill R. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;24:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D. G., Cheng Y., Zhao Y., Balk J. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:590–602. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaedler T. A. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:23264–23274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzas D., Nakamura M., Kinoshita T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:13565–13570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404058111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26443. doi: 10.1038/srep26443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan C. G. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. F. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bastow E. L., Bych K., Crack J. C., Le Brun N. E., Balk J. Plant J. 2017;89:590–600. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Kronzucker H. J., Shi W. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Macías J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E3563–E3572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701952114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H.-Q., Bauer P., Bereczky Z., Keller B., Ganal M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212448699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo E. P., Guerinot M. L. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3400–3412. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby M., Wang H. Y., Reidt W., Weisshaar B., Bauer P. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. X., Zhang J., Wang D. W., Ling H. Q. Cell Res. 2005;15:613–621. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. Cell Res. 2008;18:385–397. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:503–513. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz A. B., Hermand V., Curie C., Vert G. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T. A. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2219–2236. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Plant Cell. 2015;27:787–805. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.132704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang H., Ai Q., Liang G., Yu D. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:2478–2493. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C. M., Hindt M. N., Schmidt H., Clemens S., Guerinot M. L. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. Y. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2017–2027. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. Plant J. 2003;36:780–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19150–19155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. Plant J. 2007;51:366–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. Ann. Bot. 2010;105:1109–1117. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin L.-J. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3039–3051. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingam S. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1815–1829. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser J., Lingam S., Bauer P. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:2154–2166. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selote D., Samira R., Matthiadis A., Gillikin J. W., Long T. A. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:273–286. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.250837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M. S. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2008;22:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy C., Distelfeld A., Fahima T., Blechl A., Dubcovsky J. A. Science. 2006;314:1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1133649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa H. S. Plant Breed. 2013;132:458–471. [Google Scholar]

- Blair M. W., Izquierdo P. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012;125:1015–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodkany B. S. J. Nutr. 2013;143:1489–1493. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.176677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein J. L. J. Nutr. 2015;145:1576–1581. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.208009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas J. D. J. Nutr. 2016;146:1586–1592. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.224741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. A. T. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan N. Plant Sci. 2015;240:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg S. J. Cereal Sci. 2012;56:204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Connorton J. M., Plant Physiol., 2017. , , accepted . [Google Scholar]

- Slamet-Loedin I. H., Johnson-Beebout S. E., Impa S., Tsakirpaloglou N. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banakar R., Álvarez Fernández A., Abadía J., Capell T., Christou P. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;15:423–432. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasileva K. V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E913–E921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619268114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell R., Egli I. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;91:1461S–1467S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboy V., Young K. A., Dorsch J. A., Cook A. J. Plant Physiol. 2001;158:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth J. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2009;7:631–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N. Nature. 2017;541:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagling T., Wawer A. A., Shewry P. R., Zhao F., Fairweather-tait S. J. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:10320–10325. doi: 10.1021/jf5026295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenhardt F., Levrat-Verny M. A., Chanliaud E., Rémésy C. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:98–102. doi: 10.1021/jf049193q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latunde-Dada G. O. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:11222–11227. doi: 10.1021/jf503474f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakei Y. Rice. 2013;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koryachko A. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai H.-J., Pateyron S., Bauer P. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:211. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0899-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. Plant J. 2009;60:948–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:13407–13417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trijatmiko K. R. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19792. doi: 10.1038/srep19792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. P., Keller B., Gruissem W., Bhullar N. K. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017;130:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2808-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]