Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive esophagectomy theoretically offers advantages compared with open esophagectomy (OE). The aim of this study was to compare the early- and mid-term outcomes between video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) esophagectomy (VE) and OE in patients with esophageal cancer.

Methods

Between November 2011 and July 2015, a total of 172 patients were divided into two groups depending on the method of esophagectomy: the VE group (n=42) and the OE group (n=130). A propensity analysis that incorporated perioperative variables, such as age, sex, preoperative pulmonary function, Charlson comorbidity index, tumor location, histologic grade of the tumor, pathologic stage and operative procedure (Ivor Lewis or McKeown) was performed, and postoperative outcomes were compared.

Results

Matching based on propensity scores produced 42 patients in each group for the analysis. After propensity matching, there were only two operative mortalities in the OE group, and both died of postoperative pneumonia. The overall incidence of postoperative complications was 38.1% (16 of 42) and 57.1% (24 of 42) in the VE group and in the OE group, respectively (P=0.088). The incidence of pulmonary complications was lower in the VE group than in the OE group (9.5% vs. 40.5%, P=0.004). The 2-year overall survival and disease-free survival were not different between the two groups (74.4% and 69.5% in the VE group, 69.5% and 69.8% in the OE group, P=0.865 and P=0.513, respectively).

Conclusions

In select patients, superior short-term surgical results and equal oncological outcomes were achieved with VE compared with OE.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), open esophagectomy (OE), pulmonary complication

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the 8th most common malignancy and the 6th most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1). Despite recent advancements in multidisciplinary approaches, surgical resection is still the mainstay treatment for potentially resectable esophageal cancer (2). However, esophageal cancer surgery remains to have high postoperative morbidity and mortality. This is most likely associated with extensive and aggressive surgical procedures (2-5).

Traditionally, esophageal cancer has been surgically treated with esophagectomy via open thoracotomy, or simply, open esophagectomy (OE). Moreover, esophageal cancer requiring esophagectomy is more prevalent in elderly patients with numerous comorbidities. To reduce the physiologic stress and morbidities associated with OE, minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) has been recognized to be important (6). With improved instrumentation as well as increased exposure and experience using endoscopic surgical techniques, the demand for minimally invasive surgical approaches, like MIE, for the resection of esophageal cancer is increasing. Accordingly, there has recently been a movement to determine the feasibility, postoperative results, and potential advantages of minimally invasive approaches. MIE, compared with OE, theoretically offers advantages, such as decreased morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and more rapid return to daily activities (7). Since several techniques are considered to be MIE (thoracoscopic, laparoscopic, mediastinoscopic, hybrid, total, and robotic-assisted MIE, etc.), it would be inaccurate to compare just MIE and OE. Our study focuses on video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) esophagectomy (VE) with left lateral decubitus position, which is a more familiar and widely utilized procedure to thoracic surgeons.

Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the early- and mid-term operative outcomes between VE and OE in patients with esophageal cancer.

Methods

Patients and clinical data

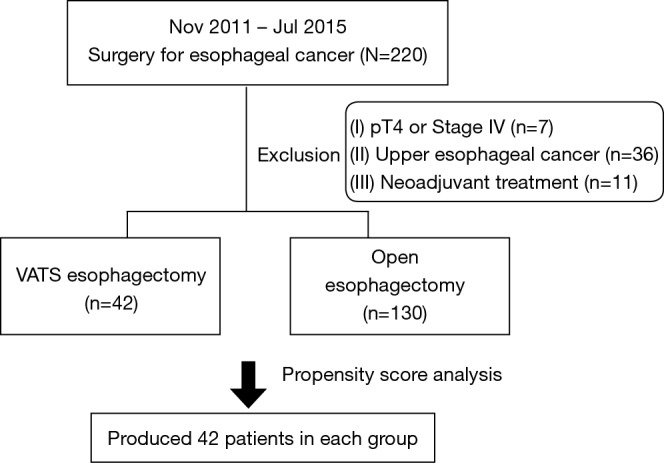

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of consecutive 220 patients who underwent esophagectomy and reconstruction with a stomach conduit in our institution for esophageal cancer between November 2011 and July 2015. We excluded patients with clinical T4 esophageal cancer (n=7), those with upper thoracic esophageal cancer (n=36), and those who underwent neoadjuvant treatment (n=11; Figure 1). The data were collected by manual review of patients’ electronic medical records, which consisted of information on preoperative patient characteristics, disease status, operative procedures, pathologic report, and postoperative outcomes. Patients were staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition TNM staging system. Each patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy, endoscopic ultrasonography, chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT), bronchoscopy, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emitted tomography (FDG-PET)/CT to determine preoperative staging. Middle thoracic esophageal cancer was defined as a tumor located 25–30 cm from the incisors, and lower thoracic esophageal cancer was defined as a tumor located 31 cm to the gastro-esophageal junction. This retrospective study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board at the National Cancer Center Korea (No. 2017-0177), and the requirement for informed patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of exclusion criteria used for patient selection. Six patients were duplicated, 4 patients had neoadjuvant treatment with upper esophageal cancer and 2 patients were upper esophageal cancer with pT4. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Surgical approach

All patients were intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube. During the thoracic procedures, patients were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, and the right lung was collapsed. In the VE operation, thoracic procedures were performed under VATS. Two ports and one working window were created [11-mm trocar: the camera was inserted 8th intercostal space (ICS) on the mid axillary line; 5-mm trocar: 6th ICS on the posterior axillary line for instrument; a 4-cm mini-thoracotomy was made in the 4th ICS applying wound protector between the anterior and mid axillary line]. Esophageal dissection and mobilization were performed in the same manner as the OE technique. All patients underwent total mediastinal lymph nodes dissection. A 3-field lymph node dissection (3-FD) was added for patients with middle thoracic esophageal cancer near the carina (8).

The azygos vein was divided with an endoscopic stapler. The thoracic duct was preserved unless in the event of direct tumor invasion or injury during esophageal or lymph node dissection. In Ivor Lewis procedure, after complete dissection between the membranous trachea and upper portion of the esophagus, intrathoracic esophagogastrostomy were performed using the whole stomach as a conduit, and anastomosis was performed with an end-to-end anastomosis stapler (EEA stapler; Autosuture, U.S. Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT, USA). In the McKeown procedure, the gastric tube was created using 75-mm and 55-mm TLC (Ethicon Ltd., Somerville, NJ, USA) staplers, and the conduit was pulled up gently through the posterior mediastinum and the cervical anastomosis was performed with an EEA stapler on the left side of the neck.

The abdominal procedure was performed with an upper median laparotomy. The stomach was dissected free with preservation of the right gastroepiploic vessels. After gastric mobilization for conduit, complete abdominal lymphadenectomy including the celiac axis, common hepatic, left gastric and distal esophagus was performed. A pyloroplasty was conducted with the finger-fracture method. The Kocher maneuver is normally not performed at our institution on a routine basis.

Perioperative management

In the initial stage, VE was indicated for patients who did not have any pleural adhesion and was not considered to be in the advanced stages of esophageal cancer. However, during the study period, indications for VE were gradually expanded to include all patients who this procedure was thought possible. After the operations, all patients underwent EGD and esophagography on postoperative days 6 and 7 consecutively. They were typically allowed to take sips of water after confirming no leakage and conduit problems, and full liquid diet was implemented on the following day. If they were able to tolerate a liquid diet, soft foods were given.

Postoperative outcomes

The postoperative outcomes of interests were operative mortality, overall and pulmonary complications, length of ICU stay, number of harvested lymph nodes, operation time, blood loss, and overall survival. Operative mortality was defined as any death occurring at any time during the same postoperative hospital stay or within 30 days of operation. We decided on the postoperative management plan by one team through mortality and morbidity conference every week. Postoperative complications included recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, pulmonary complications, arrhythmia, anastomotic leak or any conduit problem, chylothorax and postoperative bleeding. Postoperative pulmonary complications included atelectasis with sputum retention that required bronchoalveolar toileting using flexible bronchoscopy, postoperative pneumonia and either acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Postoperative pneumonia was defined by radiographic infiltration shadows with at least two of the following: temperature >37.7 °C, white blood cell count >10,000/mm3 and positive sputum culture. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was diagnosed by an evaluation of the vocal cord mobility with a flexible laryngoscopy by an otolaryngologist.

Follow-up

A follow-up was conducted every 3 months during the first 2 years, then biannually from the 2nd to the 5th year and then annually thereafter. Chest CT was performed on these occasions, and an annual examination with FDG-PET/CT and EGD was simultaneously conducted. The date of recurrence was defined as the date of the examination during which recurrence was documented.

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological features, including age, gender, body mass index, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1%), Charlson comorbidity index, tumor location, tumor type, tumor grade, pathologic T stage, pathologic N stage, operation method and 3-field dissection were compared between the VE group and the OE group. Thus, its influence on postoperative outcomes was also analyzed. Descriptive statistics were used to compare the variables between the two groups, using χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. To control for the potential differences in the baseline characteristics of patients treated with VE or OE, propensity score was utilized. By using a multivariate logistic regression model, which included all clinicopathological features, the propensity scores were computed as the conditional probability of receiving either VE or OE. Using the Greedy 81-digit match algorithm, we created propensity score-matched pairs without replacement (a 1:1 match). Comparisons between the matched groups were performed with McNemar’s test for categorical variables and paired t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Disease-free intervals and overall survival rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were compared with log-rank tests. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 software (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Between November 2011 and July 2015, a total of 172 patients who met the inclusion criteria underwent esophageal resection and reconstruction with stomach conduit in our institution. The enrolled study patients were divided into two groups: The VE group (n=42), which included patients who underwent MIE with VATS and the OE group (n=130), which included patients who underwent conventional esophagectomy with open thoracotomy. The baseline characteristics of 172 patients are summarized in Table 1. There were substantial differences between the two groups. Patients in the VE group presented more frequently with a middle thoracic esophageal cancer and patients in the OE group presented more frequently with advanced T stage. To obtain more reliable outcomes, matching based on propensity scores produced 42 patients in each group; the paired groups were well balanced (Table 2). The P values were recalculated and there were no significant differences between the two groups. Postoperative outcomes are reported in Table 3. In the unadjusted data, there were no operative mortalities in the VE group, whereas there were five operative mortalities in the OE group; this difference was not statistically significant. Postoperative complications occurred in 16 patients (38.1%) in the VE group and 62 patients (47.7%) in the OE group (P=0.277). Pulmonary complications occurred more frequently in the OE group (29.2%) than in the VE group (9.5%, P=0.010). There were no differences between the groups with respect to other specific complications. However, the operation time was longer in the VE group (P=0.025), and the number of harvested lymph nodes detected were greater in the OE group (P=0.003).

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics in the VE and OE groups before propensity score-matching.

| Variables | VE (n=42) | OE (n=130) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 40 (95.2) | 126 (97.0) | 0.605 |

| Age (years) | 63.3±7.7 | 65.6±7.6 | 0.083 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.1±2.7 | 22.6±2.6 | 0.288 |

| FEV1 predicted (%) | 104.4±18.5 | 99.7±16.4 | 0.120 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.387 | ||

| 2 | 26 (61.9) | 65 (50.0) | |

| 3 | 13 (31.0) | 55 (42.3) | |

| 4 | 3 (7.1) | 10 (7.7) | |

| Tumor location | 0.036 | ||

| Middle thoracic | 30 (71.4) | 69 (53.1) | |

| Lower thoracic | 12 (28.6) | 61 (46.9) | |

| Tumor type | 0.672 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 39 (92.9) | 123 (94.6) | |

| Others | 3 (7.1) | 7 (5.4) | |

| Tumor grade | 0.424 | ||

| Well differentiated | 11 (26.2) | 36 (27.7) | |

| Moderate differentiated | 26 (61.9) | 68 (52.3) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 5 (11.9) | 26 (20.0) | |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.023 | ||

| 1 | 28 (66.7) | 55 (42.3) | |

| 2 | 3 (7.1) | 16 (12.3) | |

| 3 | 11 (26.2) | 59 (45.4) | |

| Pathologic N stage | 0.109 | ||

| 0 | 25 (59.5) | 58 (44.6) | |

| 1 | 12 (28.6) | 38 (29.2) | |

| 2 | 5 (11.9) | 21 (16.2) | |

| 3 | 0 | 13 (10.0) | |

| Operative methods | 0.672 | ||

| Ivor Lewis | 35 (83.3) | 105 (80.8) | |

| McKeown | 7 (16.7) | 25 (19.2) | |

| 3-FD | 4 (9.5) | 27 (20.8) | 0.099 |

Data were presented as number of patients (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. Data in parenthesis indicate percentage. VE, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory in 1 second; 3-FD, 3-field dissection.

Table 2. Patients’ characteristics in the VE and OE groups after propensity score-matching.

| Variables | VE (n=42) | OE (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 40 (95.2) | 39 (92.9) | 0.665 |

| Age (years) | 63.3±7.7 | 64.3±7.2 | 0.577 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.1±2.7 | 21.9±2.9 | 0.773 |

| FEV1 predicted (%) | 104.4±18.5 | 103.2±13.9 | 0.714 |

| Charlson Comorbidity index | 0.513 | ||

| 2 | 26 (61.9) | 21 (50.0) | |

| 3 | 13 (31.0) | 20 (47.6) | |

| 4 | 3 (7.1) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Tumor location | 0.796 | ||

| Middle thoracic | 30 (71.4) | 31 (73.8) | |

| Lower thoracic | 12 (28.6) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Tumor type | 1.000 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 39 (92.9) | 39 (92.9) | |

| Others | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Tumor grade | 0.496 | ||

| Well differentiated | 11 (26.2) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Moderate differentiated | 26 (61.9) | 28 (66.7) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.914 | ||

| 1 | 28 (66.7) | 29 (69.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (7.1) | 2 (4.8) | |

| 3 | 11 (26.2) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Pathologic N stage | 0.870 | ||

| 0 | 25 (59.5) | 25 (59.5) | |

| 1 | 12 (28.6) | 13 (31.0) | |

| 2 | 5 (11.9) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Operative method | 1.000 | ||

| Ivor Lewis | 35 (83.3) | 35 (83.3) | |

| McKeown | 7 (16.7) | 7 (16.7) | |

| 3-FD | 4 (9.5) | 7 (16.7) | 0.366 |

Data were presented as number of patients (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. Data in parenthesis indicate percentage. VE, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory in 1 second; 3-FD, 3-field dissection.

Table 3. Postoperative outcomes of propensity score-unmatched and matched patients.

| Postoperative outcomes | Unadjusted | Propensity score-matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VE (n=42) | OE (n=130) | P value | VE (n=42) | OE (n=42) | P value | ||

| Operative mortality [n (%)] | 0 | 5 (3.8) | 0.197 | 0 | 2 (4.8) | 0.157 | |

| Operation time [range] (min) | 330 [235–595] | 310 [180–640] | 0.025 | 330 [235–595] | 298 [180–455] | 0.015 | |

| ICU stay [range] (days) | 1 [1–5] | 1 [1–157] | 0.175 | 1 [1–5] | 1 [1–157] | 0.143 | |

| Blood loss [range] (mL) | 200 [100–1,400] | 300 [50–1,350] | 0.055 | 200 [100–1,400] | 300 [70–1,350] | 0.297 | |

| Number of harvested LNs [range] | 31 [7–71] | 38 [7–127] | 0.003 | 31 [7–71] | 33 [7–81] | 0.198 | |

| Overall complication (at least one) [n (%)] | 16 (38.1) | 62 (47.7) | 0.277 | 16 (38.1) | 24 (57.1) | 0.088 | |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 8 (19.0) | 19 (14.6) | 0.492 | 8 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 0.782 | |

| Pulmonary complication | 4 (9.5) | 38 (29.2) | 0.010 | 4 (9.5) | 17 (40.5) | 0.004 | |

| Arrhythmia | 1 (2.4) | 3 (2.3) | 0.978 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 1.000 | |

| Anastomotic leak | 2 (4.8) | 11 (8.5) | 0.430 | 2 (4.8) | 4 (9.5) | 0.414 | |

| Chylothorax | 1 (2.4) | 5 (3.8) | 0.653 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.8) | 0.564 | |

| Postoperative bleeding | 2 (4.8) | 1 (0.8) | 0.086 | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 0.360 | |

VE, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; ICU, intensive care unit; LNs, lymph nodes.

Next, we analyzed the postoperative outcome in well-matched patients. Although, the operation time was longer in VE group (P=0.015), pulmonary complications occurred more frequently in the OE group (9.5% vs. 40.5%, P=0.004). Regarding postoperative pneumonia, there were higher occurrences in the OE group than in the VE group (31.0% vs. 7.1%, P=0.021; Table 4). In the OE group, compared with the VE group, there were greater occurrences of postoperative atelectasis needing bronchoalveolar toileting using flexible bronchoscopy (23.8% vs. 2.4%, P=0.012). The number of harvested lymph nodes was not significantly different between the two groups (31 vs. 33, P=0.198).

Table 4. Postoperative pulmonary complications between VE and OE [n (%)].

| Variables | VE (n=42) | OE (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary complications (all) | 4 (9.5) | 17 (40.5) | 0.004 |

| Atelectasis | 1 (2.4) | 10 (23.8) | 0.012 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (7.1) | 13 (31.0) | 0.021 |

| Pneumonia (medication) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (16.7) | 0.070 |

| Pneumonia (ICU care) | 2 (4.8) | 6 (14.3) | 0.289 |

| ALI or ARDS | 1 (2.4) | 5 (11.9) | 0.219 |

VE, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

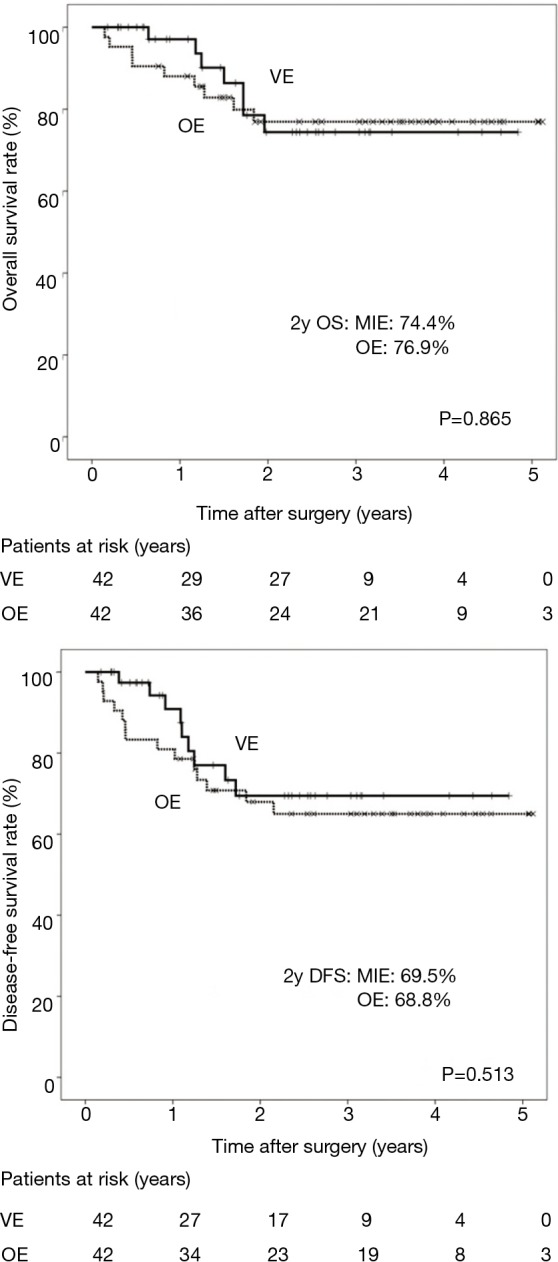

The median follow-up for the matched patients was 29.3 months, the 2-year overall survival for the VE group and OE group was 74.4% and 76.9%, respectively (Figure 2). There were no statistical differences between the two groups. The 2-year disease-free survival for the VE group and OE group was 69.5% and 68.8%, respectively. There were also no statistical differences between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Overall survival and disease-free survival between matched VE and OE groups. VE, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy.

Discussion

Recently, there has been much advancement in the multidisciplinary approaches to treating esophageal cancer. However, esophagectomy is still the mainstay treatment modality for resectable esophageal cancer, despite its high operative mortality and morbidity (2). Moreover, pulmonary complications, such as pneumonia, ARDS, and other respiratory complications, despite recent progress in anesthetic procedures and postoperative care, still remain to be the most adverse events following esophagectomy (3). These problems contribute to prolonged hospital stay, increased mortality, and higher cost of treatment (9). Variable factors, including patient age, comorbidities, postoperative pain, aspiration, postoperative atelectasis, and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury are involved in pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Surgical technique has also been regarded as key factor responsible for pulmonary complications (10).

Since the first reported MIE using thoracoscopic esophagectomy in 1992, many groups have attempted and reported various methods for MIE (6). The increase in the popularity of MIE is a result of technical advancements and development of endoscopic equipment in thoracoscopic, laparoscopic and robotic surgeries, which are all available for esophagectomy as well as extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy (10). Theoretically, MIE should reduce morbidity and show similar long-term outcomes compared with OE. However, to the best of our knowledge, advantages regarding the oncologic outcomes, such as overall survival, disease-free survival, and number of harvested lymph nodes using MIE have not been fully established (11).

In this study, we showed that VE compared with OE was associated with lower postoperative overall pulmonary complications, lower postoperative atelectasis and lower postoperative pneumonia in a study population of well-matched esophageal cancer patients. Our overall incidence of pulmonary complications and pneumonia in OE was comparable with that of other previous studies (5). The number of harvested lymph nodes was not significantly different (31 vs. 33, P=0.198) between the two groups, satisfying the requirements for the Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration data (12,13). Lagerson and colleagues suggested that a higher number of harvested lymph nodes provided better survival in esophageal cancer (2). Many surgeons believe that MIE is inappropriate in obtaining adequate lymph node harvesting and that insufficient lymph node harvesting leads to a lower incidence of pulmonary complication outcomes. Extended lymph node dissection was assumed to increase the risk of pulmonary complications. However, in our present study, harvesting an adequate number of lymph nodes was achieved by VE. We were able to compare the optimal method between VE and OE using a propensity score-matched analysis.

Many studies have previously reported methods to significantly lower the complications in MIE with prone position. Palanivelu and colleagues demonstrated that 2.3% pulmonary complications occurred in their MIE group with prone-position (7). They suggested that the prone position provided several benefits, including a good operative field of the mid-to-lower mediastinum without any retraction of the right lung, shorter operative time, and lower incidence of pulmonary complications compared with the lateral decubitus position (14,15). Concurrently, however, the prone position also has disadvantages. It is vulnerable to urgent thoracotomy conversion in the event of emergency situations like massive bleeding. In our present study, the same method of esophagectomy in the left lateral decubitus position with a double lumen endotracheal tube was performed, regardless whether it was VE or OE, since this particular method was the most familiar method for thoracic surgeons. Considering the pulmonary complications of VE, although a precise comparison may be difficult, the left lateral decubitus position technique does not seem to be inferior to the prone position technique (15,16).

There are numerous types of MIE, depending on the approach—thoracic or abdominal. Total MIE uses both laparoscope and thoracoscope, while hybrid MIE uses only one of two (11). In our study, we used hybrid MIE; for the thoracic approach, we used thoracoscope and for the abdominal approach, we used an upper median laparotomy. Hybrid MIE using the thoracic approach was chosen because (I) most thoracic surgeons are more familiar with VATS, lacking the appropriate experience of using a laparoscope, and (II) cooperation with a general surgeon is made particularly difficult due to insurance complexities in Korea. Moreover, we believed that hybrid MIE using laparoscope, compared with hybrid MIE using thoracoscope, would result in higher pulmonary complications. Given such concerns, we decided to perform hybrid MIE using thoracoscope. Compared with the study by Glatz and colleagues, who used hybrid MIE with laparoscope, our study showed a greater number of harvested lymph node and a notably lower number of pulmonary complications (17).

Generally, VE is known to have several advantages over OE, such as better cosmetic outcome with less incisions, less tissue trauma, less pain, reduced postoperative inflammatory responses, less morbidity, and early return to daily activities (18). All these advantages are strongly related to avoiding thoracotomy. As such, VE has been gaining increasing popularity among thoracic surgeons. Given that VE showed satisfying lymph node harvesting and minimal pulmonary complications, with similar mid-term results to that of OE, VE appears to have merit with respect to its efficacy and safety. However, the oncological benefits to patients undergoing VE have not been firmly established because there have been no randomized controlled trails verifying the equivalency in long-term survival of patients with VE compared with that in patients with OE (11). If many prospective studies indicate the oncological benefits of VE, VE could become one of the acceptable options for patients with esophageal cancer.

This retrospective study has several limitations. First, our analysis included only a single institutional data, therefore, selection bias was inevitable. However, the propensity score-matching carried out in this study likely provides the power to represent. Second, in terms of a propensity score-matched analysis, we were only able to use FEV1 as a preoperative factor for pulmonary function. Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which is another important factor, was not done routinely, and therefore, could not be added in the inclusion criteria. Our data would have been more reliable if we had added both of these two factors.

Our findings also conclusively revealed that VE could be a feasible and safe method in both the short- and mid-term outcomes, equivalent to OE. Considering the postoperative pulmonary complications, VE is more beneficial than OE in selective patients. VE could become one of the acceptable options for patients with esophageal cancer.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Jungnam Joo, PhD in the National Cancer Center for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

Ethical Statement: This retrospective study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board at the National Cancer Center Korea (No. 2017-0177), and the requirement for informed patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Yang CS, Chen X, Tu S. Etiology and Prevention of Esophageal Cancer. Gastrointest Tumors 2016;3:3-16. 10.1159/000443155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31462-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang W, Kato H, Tachimori Y, et al. Analysis of pulmonary complications after three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:903-8. 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00549-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinugasa S, Tachibana M, Yoshimura H, et al. Postoperative pulmonary complications are associated with worse short- and long-term outcomes after extended esophagectomy. J Surg Oncol 2004;88:71-7. 10.1002/jso.20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakhos CT, Fabian T, Oyasiji TO, et al. Impact of the surgical technique on pulmonary morbidity after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:221-6; discussion 226-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Banting S. Endoscopic oesophagectomy through a right thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1992;37:7-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palanivelu C, Prakash A, Senthilkumar R, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenectomy in prone position--experience of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:7-16. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang HJ, Lee HS, Kim MS, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis and survival for upper esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:1091-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson MK, Celauro AD, Prachand V. Prediction of major pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1494-1500; discussion 1500-1. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akaishi T, Kaneda I, Higuchi N, et al. Thoracoscopic en bloc total esophagectomy with radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;112:1533-40; discussion 1540-1. 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Cuesta MA, et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Esophageal Resection: Three-year Follow-up of the Previously Reported Randomized Controlled Trial: the TIME Trial. Ann Surg 2017;266:232-6. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng J, Wang WP, Yuan Y, et al. Adequate lymphadenectomy in patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: resecting the minimal number of lymph node stations. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:e141-6. 10.1093/ejcts/ezw015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice TW, Chen LQ, Hofstetter WL, et al. Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration : pathologic staging data. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:724-33. 10.1111/dote.12520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wullstein C, Ro-Papanikolaou HY, Klingebiel C, et al. Minimally Invasive Techniques and Hybrid Operations for Esophageal Cancer. Viszeralmedizin 2015;31:331-6. 10.1159/000438661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1887-92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh M, Uppal R, Chaudhary K, et al. Use of single-lumen tube for minimally invasive and hybrid esophagectomies with prone thoracoscopic dissection: case series. J Clin Anesth 2016;33:450-5. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glatz T, Marjanovic G, Kulemann B, et al. Hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy vs. open esophagectomy: a matched case analysis in 120 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2017;402:323-31. 10.1007/s00423-017-1550-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujimoto H, Takahata R, Nomura S, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal cancer attenuates postoperative systemic responses and pulmonary complications. Surgery 2012;151:667-73. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]