Abstract

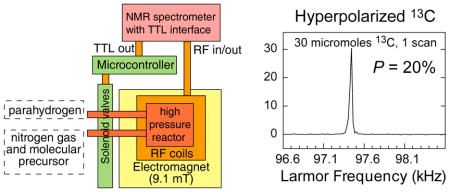

Applications of parahydrogen induced polarization (PHIP) often warrant conversion of the chemically-synthesized singlet-state spin order into net heteronuclear magnetization. In order to obtain optimal yields from the overall hyperpolarization process, catalytic hydrogenation must be tightly synchronized to subsequent radiofrequency (RF) transformations of spin order. Commercial NMR consoles are designed to synchronize applied waves on multiple channels and consequently are well-suited as controllers for these types of hyperpolarization experiments that require tight coordination of RF and non-RF events. Described here is a PHIP instrument interfaced to a portable NMR console operating with a static field electromagnet in the milliTesla regime. In addition to providing comprehensive control over chemistry and RF events, this setup condenses the PHIP protocol into a pulse-program that in turn can be readily shared in the manner of traditional pulse sequences. In this device, a TTL multiplexer was constructed to convert spectrometer TTL outputs into 24 VDC signals. These signals then activated solenoid valves to control chemical shuttling and reactivity in PHIP experiments. Consolidating these steps in a pulse-programming environment speeded calibration and improved quality assurance by enabling the B0/B1 fields to be tuned based on the direct acquisition of thermally polarized and hyperpolarized NMR signals. Performance was tested on the parahydrogen addition product of 2-hydroxyethyl propionate-1-13C-d3, where the 13C polarization was estimated to be P13C = 20 ± 2.5 % corresponding to 13C signal enhancement approximately 25 million-fold at 9.1 mT or approximately 77,000-fold 13C enhancement at 3 T with respect to thermally induced polarization at room temperature.

Keywords: NMR, hyperpolarization, parahydrogen, 13C, spectroscopy, low field, instrumentation

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Hyperpolarization of nuclear spin ensembles has advanced NMR sensitivity to a level that is now enabling detection of metabolism in living tissue on a time-scale of seconds [1–11]. The dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) technology [12–14] and its modern dissolution DNP (d-DNP) implementation [9, 15, 16] have already proven capable of producing 13C hyperpolarized contrast agents for detecting, grading, and monitoring response to therapy in tumors in preclinical settings [6, 17, 18]. These developments and a rapidly growing range of other applications suggest that hyperpolarized MR is a viable technological basis for assessing metabolism in vivo, and consequently clinical trials have now been initiated for studying human cancers with d-DNP [19].

The diagnostic potential of d-DNP in the context of its associated expense, bulk, and overall technical complexity has naturally fueled interest in lower cost alternatives [20–23] such as parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP) technique [24–27]. Although more constrained in terms of suitable precursors, PHIP has been used to efficiently hyperpolarize several molecules that have, in turn, been applied to varied applications ranging from angiography [24, 28] to the study of TCA cycle metabolism [29–31]. “Traditional”, i.e. hydrogenative, PHIP [25–27] gives high polarization but is limited to those molecules which are amenable to fast synthesis via unsaturated precursors. Despite these challenges, several new 13C targets for studying metabolism by PHIP have recently emerged in this research area [29, 32–39].

Although this manuscript is focused on describing the technical attributes of an apparatus for performing hydrogenative PHIP, the embedded pulse programmable relay network could be extended to control non-hydrogenative PHIP methods [20, 23, 40–46] or alternative forms of hyperpolarization either through direct control of valves, triggering a secondary valve controller, or by triggering the console from a secondary controller depending on experimental needs [47–51]. In order to reach or even broadly assess the potential of PHIP for application to biomedicine, instrumentation that allows for reproducible operation and facile translation would be helpful in a manner analogous to sharing traditional RF pulse sequences. Creating highly ordered polarization on long-lived nuclei such as carbonyl 13C with PHIP requires that catalytic hydrogenation be rigorously coordinated with spin transformation [52–59] as well as post-reaction chemistry [38]. Integration of chemical reaction, spin manipulation, and NMR detection in a type of hybrid pulse program streamlines device fine-tuning as conditions warrant, while facilitating collaboration and experimental replication.

The current state of PHIP polarizers can be divided into two categories based on the method used to transfer chemically synthesized (parahydrogen) spin order. The device described here used radiofrequency (RF) pulses to transfer parahydrogen spin order; this is sometimes referred to as pulsed PHIP (i.e. relying on RF pulses in a static magnetic field) [52, 53] versus alternative magnetic field cycling (MFC) methods [24, 37, 60]. While both methods have been shown to yield high polarizations, pulsed methods holding the sample stationary at a fixed magnetic field were pursued here rather than the alternative of either modulating the static field or moving the sample relative to the magnetic fields. Pulsed PHIP device configurations can be further discriminated based on the electronic controller, capability to detect in situ [33, 61], magnetic field strength, magnet type (permanent [61], superconductive [62] or electromagnet [58]), and the overall degree of portability. Specialized portable devices have been described [45], distributed spray types where synthesis and transfer are separate from detection [58, 59], integrated detection with permanent magnets, and more fixed systems using syringe pumps [56]. These and many other devices are likely to emerge as application development generates new instrumental demands.

The spectrometer-based, tunable low-field polarizer design described here allows chemical synthesis and post reaction filtering or ejection parameters to be pulse programmed alongside RF decoupling and spin order transformations. Although this setup is not limited to particular field strength, the device is demonstrated here with a simple solenoidal electromagnet powered to 9.1 mT. Indeed, we have previously described the dual-channel RF coil for permanent 48.5 mT magnet [63], while the work presented here describes the entire PHIP polarizer device. The setup presented here employs two saddle-shape RF coils operating at 388 kHz and 97.6 kHz using tunable electromagnet vs. 2020 kHz and 508 kHz [63]. We anticipate straightforward translation to lower magnetic fields as well as non-hydrogenative PHIP experiments [64, 65], and note that the electronic infrastructure described could be extended or modified for generic experimental control with a pulse programmer.

2. Methods

2.1. System schematic

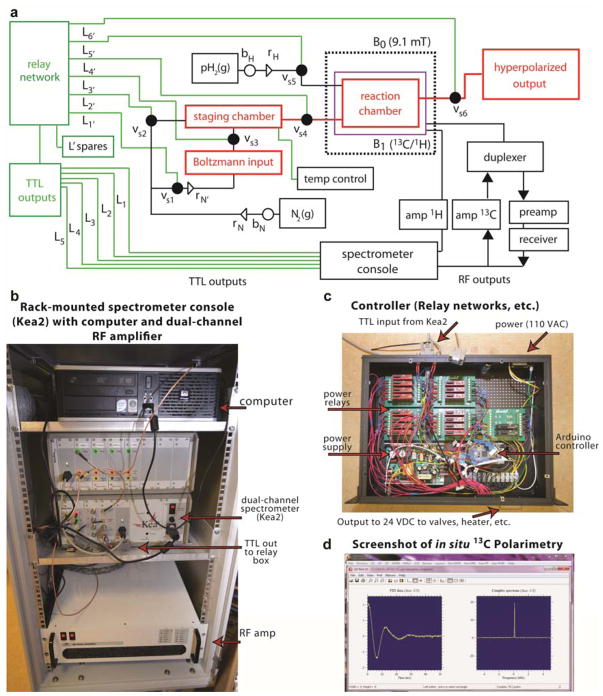

A low-field NMR spectrometer was customized to control catalytic chemical reaction with subsequent applied RF transformations and detection at a field of 9.1 mT (Figure 1). To accomplish this, a custom relay network was constructed to transform a bank of five 5.0V TTL outputs (L1–L5, Figure 1) from the spectrometer (model KEA-2, Magritek, Wellington New Zealand) into five 24VDC, high current signals (L1′–L5′) provided by solid state relays (GH3040-ND, Digikey, Thief River Falls, MN). These 24VDC output signals actuated a series of solenoid valves (Series 331, Burkert Fluidic Control Systems, Charlotte NC), which in turn allowed chemical solution (aqueous solution of unsaturated PHIP precursor and hydrogenation catalyst for molecular addition of parahydrogen) to be shuttled between holding bottle (07-201-600, Fisher Scientific), injection and reaction chambers, and finally to control the release of polarized outputs for use as biomedical contrast agents. An additional higher pressure solenoid valve was used to control the introduction of N2(g) propellant into the polarizer (Figure 1, vs2) (EH22 series, Peter Paul, New Britain, Connecticut).

Figure 1.

Spectrometer-based polarizer schematic and related photographs. a) Console TTL outputs are multiplexed from 5 lines (Li) at 5 VDC to 24 VDC using a relay network inside controller box connected to Kea2 spectrometer via TTL output. The amplified 24 VDC signals (Li’) actuate solenoid valves (vsi) to force reactants from storage into the reaction chamber and ultimately to hyperpolarized output. RF and TTL lines are controlled from within the same pulse program and, upon reaction completion, an RF sequence is turned on to transfer polarization and detect NMR signal (shown in the screenshot of Prospa software; actual sequences are provided in the SI) in the reactor chamber (also denoted as a reactor in Figure 2). Alternatively, the transfer sequence alone can be used to store magnetization before actuating Vs6 to eject hyperpolarized compounds for external use. “L’ spares” denotes additional 24 VDC signal lines that can be used for future polarizer expansion (e.g. catalyst filtration). “Boltzmann input” denotes the aqueous solution of to-be-hyperpolarized unsaturated PHIP precursor. The green boxes encompass the TTL lines (within Kea2 spectrometer, see photograph) and the physically separate dedicated relay network module (see photograph) that allows switching valves. The green line between two green boxes denotes the cable connecting Kea2 spectrometer and relay network inside the controller module (see photograph for details). rH and rN denote two-stage parahydrogen and nitrogen gas pressure regulators respectively. bH and bN denote manual tank valves on parahydrogen and nitrogen gas tanks respectively. b) the photograph of the console housing computer, NMR spectrometer and RF amplifier, c) the photograph of controller device, which connects to NMR spectrometer TTL output, d) the screenshot of 13C in situ polarimetry of hyperpolarized signals.

Pressurized N2 (g) (ultra-high purity grade, A-L Compressed Gases, Nashville, TN) was held in a position upstream of the chemical precursors and was used to propel reactants upon actuation of the selected valves as described above and depicted in Figure 1 (vs1–vs6). The N2 (g) propellant was held either in bulk storage (ca. 6.6*103 L capacity) when the polarizer was operated within the laboratory, or in portable 6.2 L tanks of ca. 1.1*103 L capacity for operation outside the laboratory. Parahydrogen was stored in 6.2 L aluminum bottles (Holley, Bowling Green, KY). Fluid flow paths were isolated from the pressurized gases in two layers: 1) through pressure-regulated (rN, Figure 1) ball valve series (bN, Figure 1), and 2) through the programmable solenoid valves (vs1–vs6, Figure 1) whose actuation timings were accessible from the spectrometer pulse program.

The reservoir containing liquid to-be-hydrogenated precursor and catalyst was selectively connected to the reaction chamber (reaction chamber, Figure 1) in two stages. In the first step, reaction chemicals were transferred from the plastic bottle to a heated (60 °C) staging chamber (staging chamber, Figure 1) held at a down-regulated pressure (rN′) (7864A11, McMaster-Carr, Aurora, OH) by actuating valve vs1 in conjunction with vs3 while vs2 was held closed. This enabled potentially fragile holding chambers to be isolated from the higher pressure N2(g) propellant. With to-be-hydrogenated precursor loaded in the staging chamber, highly enriched (~98%) parahydrogen gas (prepared separately as described previously [66]) was loaded into the reaction chamber by actuating valve vs5 while solenoid valves vs1 through vs4 were held closed. After charging the reaction chamber with parahydrogen gas at high pressure (~100 psi, ca. 7 atm), vs5 was closed and vs2 and vs4 were opened (at pressure rN), causing the solution containing to-be-hydrogenated precursor and catalyst to flow from the staging chamber into the parahydrogen-charged reaction chamber. The pressure regulator rN was held at a constant 140 psi (ca. 10 atm) differential relative to rH in order to spray the injected solution at high velocity from the staging chamber through a custom nozzle into the reaction chamber. The detailed drawings of the reactor are provided in the Supporting Information.

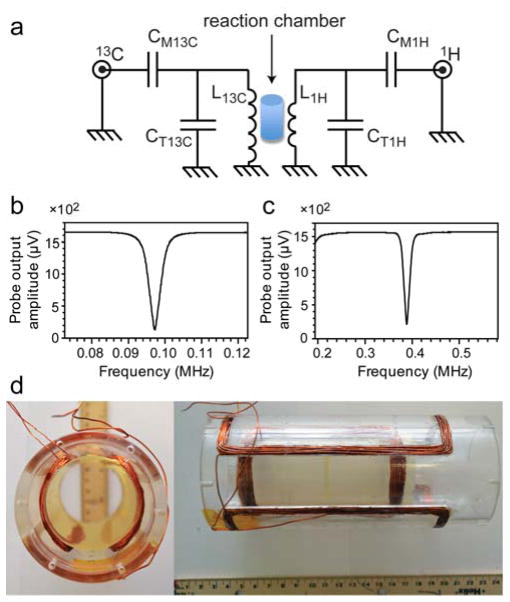

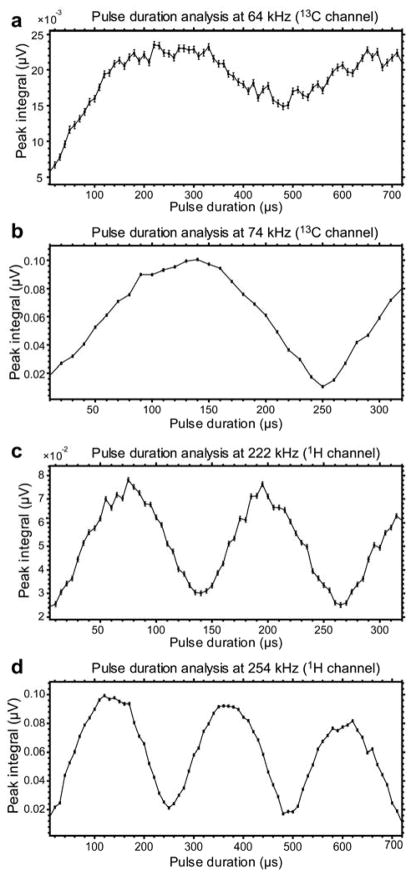

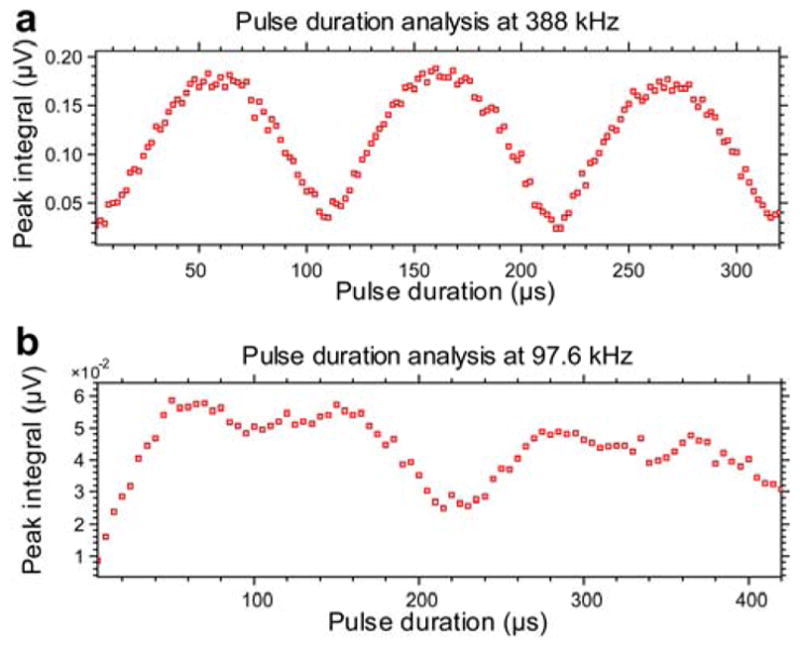

Upon completion of this gas and liquid injection sequence, the spectrometer was programmed to deliver a continuous wave 1H decoupling field to a dual resonant probe tuned to the Larmor precession frequencies of 13C and 1H at a static magnetic field of 9.1 mT (97.6 and 388 kHz, respectively) (Figure 2). The 1H decoupling would begin immediately when the injection step is initiated to ensure that chemical reaction happens under condition of continuous 1H decoupling. The sample coil of this probe consisted of a pair of concentric saddle-shaped inductors. The 1H coil was 126 mm in length with a 70 mm inner diameter (L = 153 μH), constructed by winding 16 turns (~3 layers) of 20 AWG magnet wire (7588K81, McMaster-Carr, Aurora, OH) on each side of the saddle. The 1H circuit was tuned to 388 kHz and matched to 50 Ohms with fixed, chip capacitors (25 series, Voltronics, Salisbury MD). The inner saddle coil for 13C was 82 mm in length with an inner diameter of 51 mm (L ~ 900 μH), constructed by winding 48 turns of 20 AWG magnet wire on each side (~7 layers). The 13C circuit was tuned to 97.6 kHz and matched to 50 Ohms using the following capacitor values: CT13C = 2600 pF (1000 pF, 820 pF, and 680 pF in parallel), CM13C = 1290 pF (820 pF in parallel with 470 pF) (series 25, Voltronics, Salisbury, MD). The 13C and 1H saddle coils were rotated 90° with respect to one another to minimize mutual inductance and maximize RF isolation. Proton 180° pulse durations were 108 μs at 11 W (Figure 3a) and 90° pulse durations on the 13C channel were 235 μs at 0.7 W (Figure 3b). 13C signals were acquired with a narrow band T/R switch centered at ~210 kHz.

Figure 2.

a) Dual-tuned 1H/13C probe circuit (upper panel). A pair of geometrically isolated saddle coil inductors were tuned to 388 kHz (L1H, outer coil in the photo) and 97.6 kHz (L13C, inner coil in the photo) and matched independently to 50 Ω (lower panel) using capacitances CT1H, CM1H (1H) and CT13C, CM13C (13C). b) Probe output of 13C channel (~97.6 kHz), and c) Probe output of 1H channel (~388 kHz). d) Photographs of the 1H/13C coils (top and side view).

Figure 3.

Automated RF pulse calibrations at two resonance frequencies using protons of water resonating at 388 kHz and 97.6 kHz respectively. The plots are shown as they appear in the Prospa software (1PulseDurationSweep sequence) in the magnitude mode. a) 1H channel calibration at 388 kHz. Proton 180° pulse duration is determined at 108 μs corresponding to first “null point” of the nutation curve. b) 13C channel calibration at 97.6 kHz. First, proton 360° pulse duration is determined first at ~240 μs corresponding to second “null point” of the nutation curve. 13C 90° pulse duration is computed by diving proton 360° pulse duration by 4 and multiplying it by the γ1H/γ13C and resulting in ~235 μs value.

2.2. System operation

The system schematic and function of component pieces was described above in section 2.1. In this section, operational and quality control protocols are described for generating optimal PHIP using this polarizer instrument. Each experimental session started with a quality control sequence. First, the static field electromagnet (B0, Figure 1) was powered on and allowed to equilibrate for at least one hour. Once the static field was stable, RF pulses were calibrated at both 97.6 and 388 kHz channels using an aqueous 10 mM CuSO4 solution with short T1 (1H T1 ~ 50 ms). Protons were used to calibrate both channels by adjusting the current of the power supplied to the custom electromagnet. We note that the magnetic field was the magnet was tuned to proton resonance frequencies at 97.6 kHz and 388 kHz respectively to perform these RF pulse calibrations, Figure 3. After RF pulse calibration, the aqueous CuSO4 phantom was replaced with the reaction chamber, and the components depicted in Figure 1 were connected via push-to-connect fittings and 1/8″ OD Teflon tubing (5239K24, McMaster-Carr, Aurora OH). The relay box and amplifiers were powered on, and followed by test runs with deionized water to detect leaks, malfunctions, and generally to rinse the innards of the fluid flow paths.

Following this quality control procedure, PHIP precursors were loaded into plastic storage vessels (denoted as “Boltzmann input”) and connected along with the parahydrogen gas inputs to the polarizer depicted in Figure 1. Unsaturated PHIP precursors were mixed with the Rh-based hydrogenation catalyst [54], and pH was then adjusted depending on the specific precursor under investigation (e.g. by addition of HCl or phosphate buffer solutions [33, 67]). By holding valves vs1, vs3, vs5 closed, and actuating valves vs2 and vs6 (see Figure 1), the polarizer was flushed with N2 (g) to clean and dry device fluid paths.

Having completed quality control (i.e. RF calibrations) and steps to prime the device for operation, PHIP chemical reservoirs (denoted as “Boltzmann input”) were attached to the polarizer. Referring to the labeled schematic in Figure 1, parahydrogen input pressure was set by adjusting rH. To connect parahydrogen to the device, the manual ball valve, bH, was opened. All solenoids configured to be normally closed and remained closed prior to the experimental run. Then to start the injection sequence, solenoid valves vs1 and vs3 were opened to load PHIP precursors into the staging chamber at a pressure regulated to rN′. Solenoids vs1 and vs3 were then closed to isolate the injection volume in the staging chamber. With solenoid vs1, vs2, vs3, vs4, and vs6 closed, vs5 was actuated to charge the reaction chamber with parahydrogen gas (regulated to rH). Then the PHIP chemical precursors were injected at the regulated pressure rN by opening vs2 and vs4.

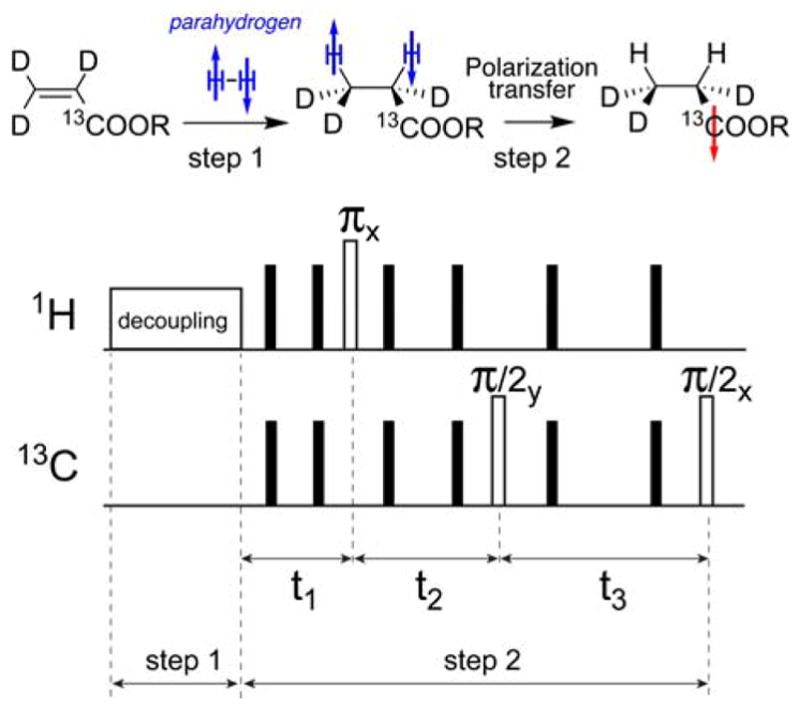

Upon this injection, catalytic addition of parahydrogen is followed by the formation of concomitant parahydrogen singlet states. In order to prevent previously formed singlet-states from evolving prior to reaction completion, a continuous wave 1H decoupling field was applied (~ 4 s) prior to the polarization transfer sequence [52]. Chemical injection timings and the application of applied fields were adjustable via a user interface (in Prospa Software, Magritek, Wellington, New Zealand) and precisely synchronized within the same programming environment. Following chemical addition of parahydrogen to the PHIP precursors, decoupling was turned off and a pulse sequence was applied to transform the singlet-state spin order of parahydrogen into net heteronuclear magnetization on a coupled heteronucleus. The RF pulse sequence developed by Goldman and co-workers [52] was employed (using the following delays: t1 = 21 ms, t2 = 37 ms, t3 = 50 ms), Figure 4, but other pulse sequences can be also used [53–55, 57, 62, 68, 69]. After completion of this step, heteronuclear magnetization was detected with the parent spectrometer by applying a heteronuclear excitation pulse and turning on the receiver. The entire hyperpolarization procedure required less than 1 minute. All other relevant delays can be found in the Prospa sequence files provided in the Supporting Information. Alternatively, the hyperpolarized liquid could also be ejected for use in a separate biomedical or basic science experiment.

Figure 4.

(Top) Schematic of evens of pairwise parahydrogen addition followed by polarization transfer event, and (bottom) then diagram of RF pulse sequence for PHIP polarization transfer from nascent parahydrogen-derived protons to 13C nucleus. Note the synchronization of two steps in chemistry and spin physics. Following the RF proton decoupling, “there are only three ‘useful’ pulses (in white). The others (black bars) are the echo pulses, at 1/4th and 3/4th of each free evolution period” [52].

3. Results and Discussion

Described here is a fully integrated parahydrogen induced polarizer system for use at low magnetic fields (~9.1 mT). A pulse-programmable relay network was interfaced to a low-field spectrometer console to enable catalytic chemistry, RF transformation (13C/1H), and detection to be controlled from a central interface. The ability to pulse program valve events to enable chemical shuttling, alongside RF transformation and detection has considerable benefits for general debugging and quality control. For example, RF pulse calibrations can be tested routinely to alleviate the consequences of possible hardware failure.

3.1. Polarizer operation at various magnetic fields

This polarizer was operated at ~48.5 mT as PHIP polarizer with different RF probe (but the same electronics and gases/liquids-handling manifold/automation, chemical reactor, etc.). For example, it was previously employed for studies of new chemistries of PHIP catalysis [70] and new PHIP contrast agent development [32]. Variable static magnetic fields were generated with a solenoidal electromagnet (for example, Figure 5 demonstrates tuning of the RF probe and the magnet to 6.0 mT corresponding to 13C and 1H resonance frequencies of 64 kHz and 254 kHz respectively) and other magnetic fields. Although other static fields can be accommodated, experimental validation was performed with a 13C/1H coil tuned to 9.1 mT.

Figure 5.

Automated RF pulse calibrations at four resonance frequencies using protons of waters on two channels of the RF probe. The plots are shown as they appear in the Prospa software (1PulseDurationSweep sequence) in the magnitude mode. a) 13C channel calibration at 74 kHz. First, proton 180° pulse duration is determined first at ~250 μs corresponding to first “null point” of the nutation curve. 13C 90° pulse duration is computed by diving proton 180° pulse duration by 2 and multiplying it by the γ1H/γ13C and resulting in ~950 μs value. b) 13C channel calibration at 64 kHz. First, proton 180° pulse duration is determined first at ~480 μs corresponding to first “null point” of the nutation curve. 13C 90° pulse duration is computed by diving proton 180° pulse duration by 2 and multiplying it by the γ1H/γ13C and resulting in ~490 μs value. c) 1H channel calibration at 222 kHz. Proton 180° pulse duration is determined at 132 μs corresponding to first “null point” of the nutation curve. d) 1H channel calibration at 254 kHz. Proton 180° pulse duration is determined at 245 μs corresponding to first “null point” of the nutation curve.

3.2. Device operation robustness

In terms of several metrics including efficiency, user-friendliness, and tunability, this spectrometer-based platform has proven robust at our site. As described below, it was possible to prepare several batches of hyperpolarized contrast agent during one hyperpolarization session (typically requiring 3–4 hours from turning on the system to finishing the device operation). With regards to the device operation several pulse-sequence based protocols were developed and they were run from the graphical user interface (GUI) provided by the vendor of Prospa software without any modification. As a result, anyone skilled in the operation of this commercially available hardware can run the hyperpolarization device.

The typical workflow requires turning on the system and warming it up for approximately 1 hour, which is sufficient for stabilizing the power supply for the main magnet, which is run in the constant-current mode (as a result, minor temperature drifts around the magnet do not alter resonance frequency during device operation). When hyperpolarizer is moved to a new location, the resonance frequencies required initial calibration by adjusting the current of B0 magnet power supply, because small fringe fields such as 0.02 mT (corresponding to proton frequency shift by ~850 Hz) result in the actual and significant resonance frequency shifts. These frequency calibrations typically required less than 30 minutes in the new polarizer location. As described above the generated B1 power (defined as nutation frequeqncy−1) on proton and 13C channels exceeded 1 kHz, and as a result, the frequency calibration to within 500 Hz on proton channel (corresponding to within 125 Hz on 13C channel) was deemed sufficient without detectable changes in the hyperpolarization efficiency. This tunability feature allows operating the RF probe without retuning it – instead, the current of B0 coil power supply is tuned to the desired frequency in the presence of background magnetic fields.

Once the resonance frequency was verified (or calibrated in case if the polarizer was moved to a new location), the RF pulse calibrations were performed (as described above). In all cases over ~1 year of polarizer use, the pulse calibrations were reproducible over the long-term polarizer operation.

From the perspective of B0 field homogeneity and B1 strength, since B1s were in excess of 1 kHz, the operation at 388 kHz and 97.6 kHz is possible even in case of relatively inhomogeneous fields. For example, the homogeneity of up to 1,000 ppm corresponding to ~388 Hz and ~98 Hz at 1H and 13C resonance frequencies respectively would be manageable, because strong B1 fields in excess of 1 kHz would allow covering the entire resonance width without deleterious effects. In our case, the operation in most cases was performed under B0 homogeneity of <500 ppm over the reactor (~56 mL volume).

3.3. Polarization transfer sequences in the context of PHIP applications

Parahydrogen induced hyperpolarization (PHIP) [27] and particularly the PASADENA [26] or ALTADENA [71] methods, require that spin order be synthesized by fast reduction of an unsaturated chemical bond. At low fields where protons are strongly coupled, the resultant singlet-state is fully preserved, but in order to be harnessed for biomedical applications, it is generally necessary to transform this spin order into net magnetization. The most common scenario is to transform this singlet-state into net heteronuclear magnetization on a long-lived nucleus such as a carbonyl-13C, but numerous other spin-systems and storage nuclei [60, 72] have been used and many further as yet undiscovered systems await. These experimental demands combined with the capability to detect NMR signals at the time of reaction favor spectrometer-based control networks where radiofrequency, acquisition, and valve actuation can be programmed and tuned from a central interface. Although specialized NMR modules have the advantage of being inexpensive, standardizing the parahydrogen-based polarization within the pulse-programming environment of a commercial spectrometer alleviates layers of technical development and simplifies tuning.

Instrumental utility can be characterized by a variety of overlapping attributes including the accessible range of applications, reproducibility, portability, and expense. In terms of range of application, this spectrometer-based approach has proven viable for PHIP. Here, we have employed the pulse sequence developed by Goldman and co-workers for polarization transfer from nascent protons to the target 13C nucleus, Figure 4 [52]. However, the device has been also shown successful for polarization transfer using hyper-SHIELDED pulse sequence (although we note that permanent magnet and other RF probe was employed with this polarizer for that goal). Moreover, we have also employed other manifolds along with this polarizer for polarization transfer from nascent proton singlet states into observable magnetization in hyperpolarized propane [73] and propane-d6 [74] motifs. These prior works clearly demonstrate the versatility of the device in terms of pulse programming and synchronization of chemistry with RF events. Other pulse sequences [53, 55, 68] for polarization transfer from nascent protons to heteronucleus (such as 13C) can be programmed with this RF console including those requiring shaped pulses [75].

Although multiple configurations are accessible, the specific implementation discussed here was equipped for a dual resonant 13C/1H PHIP experiment due primarily to the availability of 13C-labeled unsaturated precursors.

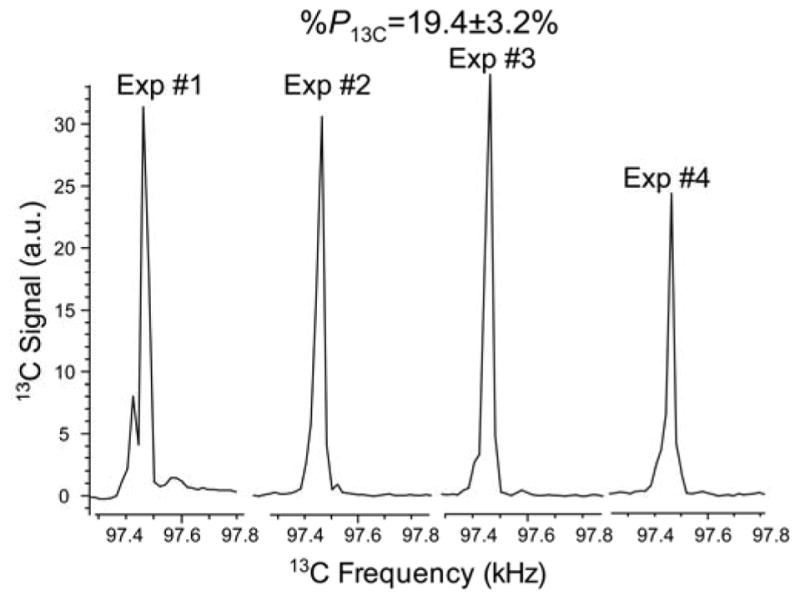

3.4. Polarization yields and reproducibility

For this validation study, a polarization yield of ~ 20 % (corresponding 13C enhancement of approximately 25 million-fold at this reference low field of 9.1 mT or approximately 77,000-fold at 3 T with respect to thermally induced polarization at room temperature, was detected on 13C in 2-hydroxyethyl propionate-1-13C-d3 following the PHIP reaction and polarization transfer from parahydrogen, Figure 6). The spectrometer-based architecture should also enable the experimental parameter space to be systematically explored for further improvement of signal enhancement [35, 57]. In terms of reproducibility, this experimental setup has performed predictably and has consistently yielded high polarization levels on the order of twenty percent or more in PHIP experiments. Figure 7 shows four PHIP hyperpolarization experiments performed during the same ~3–4-hour-long session demonstrating the average 13C polarization %P13C of 19.4% with standard deviation of 3.2%.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic for addition of parahydrogen to 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate-1-13C-d3 (HEA) to form 2-hydroxyethyl propionate-1-13C-d3 (HEP) (top). (b) Boltzmann polarized 1H spectrum acquired from an aqueous solution containing 2.7 moles of the reaction product for comparison. (c) 13C spectrum of hyperpolarized 2-hydroxyethyl propionate-1-13C-d3 (HEP).

Figure 7.

Reproducibility of 13C hyperpolarization of 2-hydroxyethyl propionate-1-13C-d3 (HEP): four spectra corresponding to experimental series performed during the same session are provided with an averaged 13C polarization %P13C of 19.4% and standard deviation of 3.2%.

3.5. Comparison of the polarizer to other published designs and potential improvements

The dual-tuned probe used a pair of geometrically decoupled saddle coils; a larger proton saddle coil was used to ensure homogeneous B1 over extended cylindrical sample dimensions, while the 13C sample coil was tightly contoured to the sample volume in order to maximize detection sensitivity. Since the channels are independent, detecting at different X-nuclear frequencies requires only that capacitance be added or subtracted (Figure 2, CT13C, CM13C). Figure 5 demonstrates example of RF probe calibrations at different resonance frequencies. Concentric saddle coils ensure uniform fields (Figure 3) and provided excellent SNR in our experiments (Figure 6), but detection sensitivity could likely be improved further by using an inner solenoidal detector (generally speaking the use of solenoid vs. saddle-shaped coil improves SNR by a factor of ~3 [76]). Borowiak and coworkers recently demonstrated this type of coil arrangement with detection down to a field of 1.8 mT [45].

Assessing the advantages of this experimental setup to others would likely depend on the desired application as well as the hardware and personnel available. In terms of mechanical or electrical complexity, parahydrogen can be reacted with substrate molecules by bubbling parahydrogen through a solution containing catalyst and unsaturated precursor molecules [77]. Reaction yields using this setup have been shown to be sufficiently high for basic science, but to achieve higher yields a variety of other approaches have been pursued when applied to biomedicine. For example, Hövener and co-workers previously described a spray-type polarizer where the electronics were driven by LabView (National Instruments, Austin, TX) [58, 59]. In order to calibrate this device, pulses delivered at the X field were measured externally in another spectrometer. The absence of an integrated NMR receiver reduces the instrumental cost but does lead to longer calibration and debugging procedures. More recently, Borowiak and co-workers demonstrated a low field electromagnetic polarizer system with an onboard detector that could access 1.8 mT [45]. A reasonable perspective is that all of these devices have merit; varied configurations expand the range of access.

The polarizer described here uses a custom TTL multiplexing module to transform spectrometer outputs into valve actuations. The advantage of this approach is that chemical synthesis steps are easily programmable from a central interface alongside RF pulses and acquisitions. The TTL multiplexer acts a modular extension of the spectrometer, and when connected to the tubing, chambers, nozzles, valves, and reactor chamber shown in Figure 1, enables PASADENA/PHIP experiments to be performed directly from the spectrometer console.

3.6. Operation considerations near MRI scanners

Polarizing at low magnetic fields with an electromagnet has several practical advantages for applications to biomedicine. Preclinical and clinical research facilities are typically equipped with high-field MR systems configured with standard fast imaging protocols. PHIP spin order is preferentially generated at low fields where the initial singlet-state is fully retained, and then transferred to the bore of a superconducting high-field magnet for imaging. The fringe field of the imaging magnet shifts the polarizer field, and therefore the polarizer field must be calibrated when brought into proximity. With permanent magnets, the static field cannot be adjusted, so in order to compensate the polarizer must either be shielded with expensive mu-metal or moved further away [61]. Both options are feasible, but the electromagnet enables this effect to be easily reconciled, because the effect of the fringe field (on B0 field of the PHIP polarizer) induced by the high-field MRI scanner can be compensated by adjusting the electromagnet current. Electromagnets such as the one used here are also straightforward to build and inexpensive in comparison to permanent magnets.

4. Conclusions

A portable and centrally controlled parahydrogen polarizer instrument operating at a low magnetic field of 9.1 mT was fully described that enables reproducible production of ordered spin ensembles by the PASADENA method of parahydrogen induced hyperpolarization. The device uses a portable, dual-channel NMR spectrometer core, operates at a tunable (electromagnetic) B0 field of 9.1 mT, and is equipped with an efficient dual-resonant probe circuit for detecting 13C or protons directly at 9.1 mT. This polarizer design addresses several issues important for translating PASADENA to biomedical applications. Experimental variables are controlled comprehensively through a central NMR console, which rigorously synchronizes the catalytic chemical synthesis of spin order with RF transformation to the net heteronuclear magnetization that is typically imaged in vivo. Central control from a spectrometer also speeds calibration and improves quality assurance, by enabling the B0/B1 fields to be tuned based on the direct acquisition of thermally polarized and hyperpolarized NMR signals. The equipment was tested on the parahydrogen addition product of 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate-1-13C-d3, whereupon conversion of the initial singlet state of nascent protons to net heteronuclear magnetization, 13C polarization P was estimated to be 20 % ± 2.5 % corresponding to 13C signal enhancement of approximately 25-million-fold at this reference low field of 9.1 mT or approximately 77,000-fold at 3 T with respect to thermally induced polarization at room temperature. The central control of the hyperpolarization could also be useful for non-hydrogenative PHIP experiments [43, 64, 78–80] as well as in the context heterogeneous PHIP experiments [81, 82]. For biomedical applications, we anticipate that this design will be especially useful to laboratories already equipped with low field imaging consoles, and additionally, for basic science applications this polarizer design should facilitate translation of PASADENA to multidimensional NMR experiments.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding support from 1R21GM107947, NIH ICMIC 5P50 CA128323-03, 5R00 CA134749-03, 3R00CA134749-02S1, DoD (CDMRP Breast Cancer Program Era of Hope Award W81XWH-12-1-0159/BC112431). We also thank Prof. John C. Gore for financial and other support of this project.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site: reactor components’ drawings; Prospa macros with TTL lines’ multiplexing; Arduino-based controller software.

References

- 1.Brindle KM. Imaging Metabolism with Hyperpolarized 13C-Labeled Cell Substrates. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6418–6427. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golman K, in’t Zandt R, Thaning M. Real-time metabolic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11270–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601319103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Brindle K, Chekmenev EY, Comment A, Cunningham CH, DeBerardinis RJ, Green GG, Leach MO, Rajan SS, Rizi RR, Ross BD, Warren WS, Malloy CR. Analysis of Cancer Metabolism by Imaging Hyperpolarized Nuclei: Prospects for Translation to Clinical Research Neoplasia. 2011;13:81–97. doi: 10.1593/neo.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolaou P, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques for Biomedicine. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:3156–3166. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barskiy DA, Coffey AM, Nikolaou P, Mikhaylov DM, Goodson BM, Branca RT, Lu GJ, Shapiro MG, Telkki VV, Zhivonitko VV, Koptyug IV, Salnikov OG, Kovtunov KV, Bukhtiyarov VI, Rosen MS, Barlow MJ, Safavi S, Hall IP, Schröder L, Chekmenev EY. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques of Gases. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:725–751. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day SE, Kettunen MI, Gallagher FA, Hu DE, Lerche M, Wolber J, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Brindle KM. Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized C-13 magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/nm1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, in’t Zandt R, Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Golman K, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized C-13-labelled bicarbonate. Nature. 2008;453:940–U973. doi: 10.1038/nature07017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comment A, Merritt ME. Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance as a Sensitive Detector of Metabolic Function. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7333–7357. doi: 10.1021/bi501225t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Boebinger GS, Comment A, Duckett S, Edison AS, Engelke F, Griesinger C, Griffin RG, Hilty C, Maeda H, Parigi G, Prisner T, Ravera E, van Bentum J, Vega S, Webb A, Luchinat C, Schwalbe H, Frydman L. Facing and Overcoming Sensitivity Challenges in Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:9162–9185. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comment A. Dissolution DNP for in vivo preclinical studies. J Magn Reson. 2016;264:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross BD, Bhattacharya P, Wagner S, Tran T, Sailasuta N. Hyperpolarized MR Imaging: Neurologic Applications of Hyperpolarized Metabolism. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:24–33. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carver TR, Slichter CP. Polarization of Nuclear Spins in Metals. Phys Rev. 1953;92:212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carver TR, Slichter CP. Experimental Verification OF The Overhauser Nuclear Polarization Effect. Phys Rev. 1956;102:975–980. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overhauser AW. Polarization of Nuclei in Metals. Phys Rev. 1953;92:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. On the present and future of dissolution-DNP. J Magn Reson. 2016;264:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, Kohler SJ, Tropp J, Hurd RE, Yen YF, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Hyperpolarized C-13 Lactate, Pyruvate, and Alanine: Noninvasive Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Detection and Grading. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8607–8615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golman K, Petersson JS. Metabolic imaging and other applications of hyperpolarized C-13. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:932–942. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Larson PEZ, Harzstark AL, Ferrone M, van Criekinge M, Chang JW, Bok R, Park I, Reed G, Carvajal L, Small EJ, Munster P, Weinberg VK, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Chen AP, Hurd RE, Odegardstuen LI, Robb FJ, Tropp J, Murray JA. Metabolic Imaging of Patients with Prostate Cancer Using Hyperpolarized 1-C-13 Pyruvate. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:198ra108. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams RW, Aguilar JA, Atkinson KD, Cowley MJ, Elliott PIP, Duckett SB, Green GGR, Khazal IG, Lopez-Serrano J, Williamson DC. Reversible Interactions with para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science. 2009;323:1708–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.1168877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lisitza N, Muradian I, Frederick E, Patz S, Hatabu H, Chekmenev EY. Toward C-13 hyperpolarized biomarkers produced by thermal mixing with hyperpolarized Xe-129. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:044508. doi: 10.1063/1.3181062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch ML, Kalechofsky N, Belzer A, Rosay M, Kempf JG. Brute-Force Hyperpolarization for NMR and MRI. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8428–8434. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theis T, Truong ML, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, Shi F, Goodson BM, Warren WS, Chekmenev EY. Microtesla SABRE Enables 10% Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Spin Polarization. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1404–1407. doi: 10.1021/ja512242d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golman K, Axelsson O, Johannesson H, Mansson S, Olofsson C, Petersson JS. Parahydrogen-induced polarization in imaging: Subsecond C-13 angiography. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:1–5. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowers CR, Weitekamp DP. Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical-Reaction and Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance. Phys Rev Lett. 1986;57:2645–2648. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowers CR, Weitekamp DP. Para-Hydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5541–5542. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenschmid TC, Kirss RU, Deutsch PP, Hommeltoft SI, Eisenberg R, Bargon J, Lawler RG, Balch AL. Para Hydrogen Induced Polarization In Hydrogenation Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharya P, Harris K, Lin AP, Mansson M, Norton VA, Perman WH, Weitekamp DP, Ross BD. Ultra-fast three dimensional imaging of hyperpolarized C-13 in vivo. Magn Reson Mater Phy. 2005;18:245–256. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacharias NM, Chan HR, Sailasuta N, Ross BD, Bhattacharya P. Real-Time Molecular Imaging of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolism in Vivo by Hyperpolarized 1-C-13 Diethyl Succinate. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:934–943. doi: 10.1021/ja2040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattacharya P, Chekmenev EY, Perman WH, Harris KC, Lin AP, Norton VA, Tan CT, Ross BD, Weitekamp DP. Towards hyperpolarized 13C-succinate imaging of brain cancer. J Magn Reson. 2007;186:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chekmenev EY, Hovener J, Norton VA, Harris K, Batchelder LS, Bhattacharya P, Ross BD, Weitekamp DP. PASADENA hyperpolarization of succinic acid for MRI and NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4212–4213. doi: 10.1021/ja7101218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. PASADENA Hyperpolarized 13C Phospholactate. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3957–3960. doi: 10.1021/ja210639c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. Parahydrogen Induced Polarization of 1-13C-Phospholactate-d2 for Biomedical Imaging with >30,000,000-fold NMR Signal Enhancement in Water. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5601–5605. doi: 10.1021/ac500952z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shchepin RV, Pham W, Chekmenev EY. Dephosphorylation and biodistribution of 1-13C-phospholactate in vivo. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2014;57:517–524. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Truong ML, Wilkens K, Pham W, Chekmenev EY. Open-Source Automated Parahydrogen Hyperpolarizer for Molecular Imaging Using 13C Metabolic Contrast Agents. Anal Chem. 2016;88:8279–8288. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Coffey AM, Manzanera Esteve IV, Chekmenev EY. Efficient Synthesis of Molecular Precursors for Para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization of Ethyl Acetate-1-13C and Beyond. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:6071–6074. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavallari E, Carrera C, Boi T, Aime S, Reineri F. Effects of Magnetic Field Cycle on the Polarization Transfer from Parahydrogen to Heteronuclei through Long-Range J-Couplings. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:10035–10041. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b06222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reineri F, Boi T, Aime S. ParaHydrogen Induced Polarization of 13C carboxylate resonance in acetate and pyruvate. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5858. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhattacharya P, Chekmenev EY, Reynolds WF, Wagner S, Zacharias N, Chan HR, Bünger R, Ross BD. Parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP) hyperpolarized MR receptor imaging in vivo: a pilot study of 13C imaging of atheroma in mice. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1023–1028. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams RW, Duckett SB, Green RA, Williamson DC, Green GGR. A theoretical basis for spontaneous polarization transfer in non-hydrogenative parahydrogen-induced polarization. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:194505. doi: 10.1063/1.3254386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowley MJ, Adams RW, Atkinson KD, Cockett MCR, Duckett SB, Green GGR, Lohman JAB, Kerssebaum R, Kilgour D, Mewis RE. Iridium N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Magnetization Transfer from para-Hydrogen. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6134–6137. doi: 10.1021/ja200299u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green RA, Adams RW, Duckett SB, Mewis RE, Williamson DC, Green GGR. The theory and practice of hyperpolarization in magnetic resonance using parahydrogen. Prog Nucl Mag Res Spectrosc. 2012;67:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Theis T, Truong M, Coffey AM, Chekmenev EY, Warren WS. LIGHT-SABRE enables efficient in-magnet catalytic hyperpolarization. J Magn Reson. 2014;248:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Truong ML, Theis T, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, Shi F, Goodson BM, Warren WS, Chekmenev EY. 15N Hyperpolarization By Reversible Exchange Using SABRE-SHEATH. J Phys Chem C. 2015;119:8786–8797. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borowiak R, Schwaderlapp N, Huethe F, Lickert T, Fischer E, Bär S, Hennig J, Elverfeldt D, Hövener JB. A battery-driven, low-field NMR unit for thermally and hyperpolarized samples. Magn Reson Mater Phy. 2013;26:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s10334-013-0366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hovener JB, Schwaderlapp N, Lickert T, Duckett SB, Mewis RE, Highton LAR, Kenny SM, Green GGR, Leibfritz D, Korvink JG, Hennig J, von Elverfeldt D. A hyperpolarized equilibrium for magnetic resonance. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2946. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikolaou P, Coffey AM, Walkup LL, Gust BM, Whiting N, Newton H, Barcus S, Muradyan I, Dabaghyan M, Moroz GD, Rosen M, Patz S, Barlow MJ, Chekmenev EY, Goodson BM. Near-unity nuclear polarization with an ‘open-source’ 129Xe hyperpolarizer for NMR and MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14150–14155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306586110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikolaou P, Coffey AM, Barlow MJ, Rosen M, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. Temperature-Ramped 129Xe Spin Exchange Optical Pumping. Anal Chem. 2014;86:8206–8212. doi: 10.1021/ac501537w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nikolaou P, Coffey AM, Ranta K, Walkup LL, Gust B, Barlow MJ, Rosen MS, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. Multi-Dimensional Mapping of Spin-Exchange Optical Pumping in Clinical-Scale Batch-Mode 129Xe Hyperpolarizers. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:4809–4816. doi: 10.1021/jp501493k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nikolaou P, Coffey AM, Walkup LL, Gust B, LaPierre C, Koehnemann E, Barlow MJ, Rosen MS, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. A 3D-Printed High Power Nuclear Spin Polarizer. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:1636–1642. doi: 10.1021/ja412093d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikolaou P, Coffey AM, Walkup LL, Gust BM, Whiting NR, Newton H, Muradyan I, Dabaghyan M, Ranta K, Moroz G, Patz S, Rosen MS, Barlow MJ, Chekmenev EY, Goodson BM. XeNA: An automated ‘open-source’ 129Xe hyperpolarizer for clinical use. Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;32:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman M, Johannesson H. Conversion of a proton pair para order into C-13 polarization by rf irradiation, for use in MRI. C R Physique. 2005;6:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldman M, Johannesson H, Axelsson O, Karlsson M. Design and implementation of C-13 hyperpolarization from para-hydrogen, for new MRI contrast agents. C R Chimie. 2006;9:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai C, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Chekmenev EY, Waddell KW. Efficient transformation of parahydrogen spin order into heteronuclear magnetization. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:1219–1224. doi: 10.1021/jp3089462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kadlecek S, Emami K, Ishii M, Rizi R. Optimal transfer of spin-order between a singlet nuclear pair and a heteronucleus. J Magn Reson. 2010;205:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kadlecek S, Vahdat V, Nakayama T, Ng D, Emami K, Rizi R. A simple and low-cost device for generating hyperpolarized contrast agents using parahydrogen. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:933–942. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bär S, Lange T, Leibfritz D, Hennig J, Elverfeldt Dv, Hövener J-B. On the spin order transfer from parahydrogen to another nucleus. J Magn Reson. 2012;225:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hövener JB, Chekmenev EY, Harris KC, Perman W, Robertson L, Ross BD, Bhattacharya P. PASADENA hyperpolarization of 13C biomolecules: equipment design and installation. Magn Reson Mater Phy. 2009;22:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0155-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hövener JB, Chekmenev EY, Harris KC, Perman W, Tran T, Ross BD, Bhattacharya P. Quality assurance of PASADENA hyperpolarization for 13C biomolecules. Magn Reson Mater Phy. 2009;22:123–134. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reineri F, Viale A, Ellena S, Alberti D, Boi T, Giovenzana GB, Gobetto R, Premkumar SSD, Aime S. N-15 Magnetic Resonance Hyperpolarization via the Reaction of Parahydrogen with N-15-Propargylcholine. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11146–11152. doi: 10.1021/ja209884h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waddell KW, Coffey AM, Chekmenev EY. In situ Detection of PHIP at 48 mT: Demonstration using a Centrally Controlled Polarizer. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:97–101. doi: 10.1021/ja108529m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt AB, Berner S, Schimpf W, Müller C, Lickert T, Schwaderlapp N, Knecht S, Skinner JG, Dost A, Rovedo P, Hennig J, von Elverfeldt D, Hövener JB. Liquid-state carbon-13 hyperpolarization generated in an MRI system for fast imaging. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Wilkens K, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. A Large Volume Double Channel 1H-X RF Probe for Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance at 0.0475 Tesla. J Magn Reson. 2012;220:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barskiy DA, Kovtunov KV, Koptyug IV, He P, Groome KA, Best QA, Shi F, Goodson BM, Shchepin RV, Truong ML, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. In Situ and Ex Situ Low-Field NMR Spectroscopy and MRI Endowed by SABRE Hyperpolarization. ChemPhysChem. 2014;15:4100–4107. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hövener JB, Knecht S, Schwaderlapp N, Hennig J, von Elverfeldt D. Continuous Re-hyperpolarization of Nuclear Spins Using Parahydrogen: Theory and Experiment. ChemPhysChem. 2014;15:2451–2457. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feng B, Coffey AM, Colon RD, Chekmenev EY, Waddell KW. A pulsed injection parahydrogen generator and techniques for quantifying enrichment. J Magn Reson. 2012;214:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coffey AM, Feldman MA, Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Truong ML, Pham W, Chekmenev EY. High-resolution hyperpolarized in vivo metabolic 13C spectroscopy at low magnetic field (48.7 mT) following murine tail-vein injection. J Magn Reson. 2017;281:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haake M, Natterer J, Bargon J. Efficient NMR pulse sequences to transfer the parahydrogen-induced polarization to hetero nuclei. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8688–8691. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pravdivtsev AN, Yurkovskaya AV, Lukzen NN, Vieth HM, Ivanov KL. Exploiting level anti-crossings (LACs) in the rotating frame for transferring spin hyperpolarization. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:18707–18719. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01445f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization with a Rh-Based Monodentate Ligand in Water. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:3281–3285. doi: 10.1021/jz301389r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pravica MG, Weitekamp DP. Net NMR Alighnment By Adiabatic Transport of Parahydrogen Addition Products To High Magnetic Field. Chem Phys Lett. 1988;145:255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bales LB, Kovtunov KV, Barskiy DA, Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Kovtunova LM, Bukhtiyarov AV, Feldman MA, Bulchtiyarov VI, Chekmenev EY, Koptyug IV, Goodson BM. Aqueous, Heterogeneous para-Hydrogen-Induced N-15 Polarization. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:15304–15309. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b05912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kovtunov KV, Truong ML, Barskiy DA, Koptyug IV, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY. Long-lived Spin States for Low-field Hyperpolarized Gas MRI. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:14629–14632. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kovtunov KV, Truong ML, Barskiy DA, Salnikov OG, Bukhtiyarov VI, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Koptyug IV, Chekmenev EY. Propane-d6 Heterogeneously Hyperpolarized by Parahydrogen. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118:28234–28243. doi: 10.1021/jp508719n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pravdivtsev AN, Yurkovskaya AV, Lukzen NN, Ivanov KL, Vieth HM. Highly Efficient Polarization of Spin-1/2 Insensitive NMR Nuclei by Adiabatic Passage through Level Anticrossings. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5:3421–3426. doi: 10.1021/jz501754j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoult DI, Richards RE. The signal-to-noise ratio of the nuclear magnetic resonance experiment. J Magn Reson. 1976;24:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roth M, Kindervater P, Raich HP, Bargon J, Spiess HW, Muennemann K. Continuous H-1 and C-13 Signal Enhancement in NMR Spectroscopy and MRI Using Parahydrogen and Hollow-Fiber Membranes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8358–8362. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pravdivtsev AN, Yurkovskaya AV, Vieth HM, Ivanov KL. Spin mixing at level anti-crossings in the rotating frame makes high-field SABRE feasible. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:24672–24675. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03765k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pravdivtsev AN, Yurkovskaya AV, Zimmermann H, Vieth HM, Ivanov KL. Transfer of SABRE-derived hyperpolarization to spin-1/2 heteronuclei. RSC Adv. 2015;5:63615–63623. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coffey AM, Kovtunov KV, Barskiy D, Koptyug IV, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, He P, Groome KA, Best QA, Shi F, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. High-resolution Low-field Molecular MR Imaging of Hyperpolarized Liquids. Anal Chem. 2014;86:9042–9049. doi: 10.1021/ac501638p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kovtunov KV, Barskiy DA, Salnikov OG, Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Kovtunova LM, Bukhtiyarov VI, Koptyug IV, Chekmenev EY. Toward production of pure 13C hyperpolarized metabolites using heterogeneous parahydrogen-induced polarization of ethyl[1-13C]acetate. RSC Adv. 2016;6:69728–69732. doi: 10.1039/C6RA15808K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kovtunov KV, Barskiy DA, Shchepin RV, Salnikov OG, Prosvirin IP, Bukhtiyarov AV, Kovtunova LM, Bukhtiyarov VI, Koptyug IV, Chekmenev EY. Production of Pure Aqueous 13C-Hyperpolarized Acetate by Heterogeneous Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:16446–16449. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]