Abstract

Rationale:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) occurs primarily in pediatric population, or secondary to malignancy, infection, or autoimmune disease. This disease is rare and prognosis is generally poor. Only a small number of cases during pregnancy have been reported in literature.

Patient concerns:

We report a case of pregnancy-associated HLH secondary to natural killer (NK)/T cells lymphoma. She was admitted at 30 weeks and 3 days of pregnancy with complaints of abdominal pain and fever as high as 39.2°C. The patient was found to have splenomegaly, pancytopenia, and acute hepatic failure.

Diagnoses:

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed focal hemophagocytosis and atypical lymphoid cells. The splenic pulp also contained a large number of tissue cells proliferating and devouring mature red blood cells, lymphocytes, and cell debris. On the basis of these findings, we diagnosed the case as pregnancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to NK/T cells lymphoma.

Interventions:

Treatment consisted with dexamethasone and etoposide in combination with rituximab.

Outcomes:

Due to timely termination of pregnancy, the neonate was in good condition. However, the patient died on the 18th day postoperation due to multiorgan failure.

Lessons:

We recommend that HLH be considered as differential diagnosis in a pregnant patient complaining of persistent fever, cytopenia, or declining clinical condition despite delivery of the baby. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential and fetal outcomes should also be considered. The decision to terminate a pregnancy and initiate chemotherapy during pregnancy with malignancy-associated HLH (M-HLH) needs to be further investigated in a larger cohort.

Keywords: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, NK/T cells lymphoma, pregnancy, treatment

1. Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare disorder characterized by histiocyte activation associated with a hyperinflammatory state and phagocytosis of hematopoietic elements.[1] The major signs and symptoms of HLH are fever, cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, liver dysfunction, elevated levels of ferritin, and serum transaminases.[2,3] HLH is usually categorized into either primary HLH based on hereditary factors or secondary HLH associated with several pathologies, such as infection, malignancy, and autoimmune disease.[2] There are a few cases of HLH during pregnancy have been reported; furthermore, less reports have documented malignancy associated HLH during pregnancy.[4] We report a case of natural killer (NK)/T cells lymphoma during pregnancy associated with HLH. This case could provide clinicians critical insight into the manifestation and treatment of this rare condition.

2. Case report

A 27-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 0, had an uneventful pregnancy until 30 weeks’ gestation. The patient's medical and family history were unremarkable. She was admitted at 30 weeks and 3 days of pregnancy with complaints of abdominal pain, and fever as high as 39.2 °C. Upon admission, her vital signs were as follows: body temperature, 38.9 °C; blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; and heart rate, 115 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed marked splenomegaly, but no swelling of superficial lymph nodes or tumor mass indicative of lymphoma were detected. Initial laboratory studies showed cytopenia with a hemoglobin level of 7.9 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count of 0.92 × 109/L, and a platelet count of 25 × 109/L. Liver function tests were anomalous; elevated alanine aminotransferase 72 U/L (normal range, 4–33 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase 463 U/L (normal range, 4–32 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase, (1799 U/L; normal range, 119–229 U/L), C-reactive protein (19.5 mg/dL), hypofibrinogenemia (0.94 g/L; normal range, 2–4 g/L), and serum ferritin (438,600 ng/mL; normal range, 6.2–138 ng/mL) were also elevated. Prothrombin time was prolonged (international normalized ratio, 1.90), while fibrinogen degradation product was elevated (48.7 μg/mL; normal range, <4 μg/mL). An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated splenic swelling and it was 9.8 cm thick. Viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, and hepatitis B and C virus were all negative.

Although optimal management was provided, there was no relief of her presenting symptoms. Furthermore, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were further elevated to 163 and 825 U/L, respectively. Her general status was deteriorating. At 30 weeks and 4 days of gestation, an emergency cesarean section was performed following evidence of fetal distress. A 1750 g male infant was delivered with Apgar scores of 5 to 8 points at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The neonate was in good condition except for respiratory distress syndrome associated with prematurity. The placenta showed no macroscopic abnormalities. However, the patient's condition was still on the decline postoperation up to disseminated intravascular coagulation. She was transfused with 2 units of packed red blood cells and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma. Her hemoglobin still further dropped to 5.7 g/dL and the drainage fluid was tainted pink. The abdominal ultrasound revealed a swollen spleen with thickness of 6.3 cm. Based on the assumption of a probable postoperative abdominal hemorrhage, the patient underwent an explorative laparotomy and during which a ruptured spleen was found and a splenectomy was performed. In spite of the emergency procedure, there was no improvement in her condition and the patient consequently developed degrading liver function, acute respiratory distress, and sustained kidney injury. She was transferred to the intensive care unit and placed under pulse contour cardiac output (PiCCO) monitor, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and her breathing was assisted by a ventilator. Multiple blood products were transfused due to persistent cytopenia and coagulopathy. Despite these measures, her condition still depreciated.

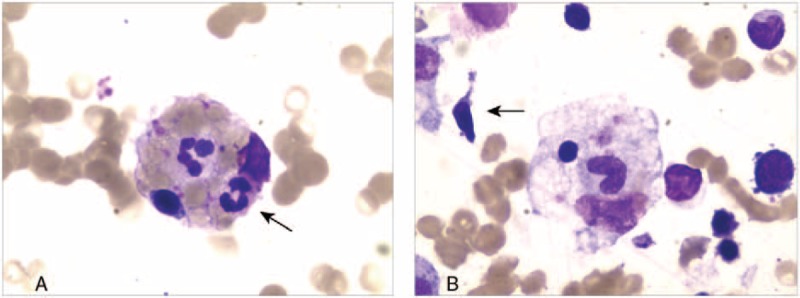

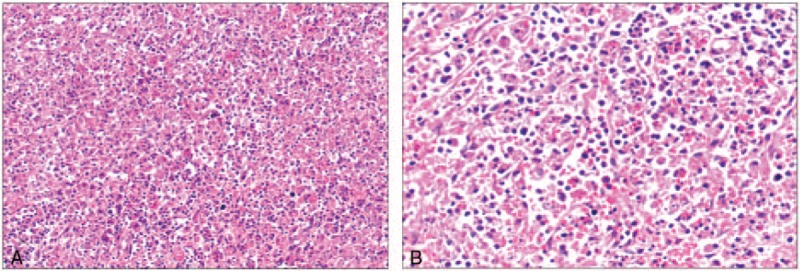

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed focal hemophagocytosis and atypical lymphoid cells (Fig. 1). No abnormal clone cells were found in peripheral blood flow cytometry. Flow cytometry also failed to detect PNH clones in red blood and white blood cells. Myeloid flow immune-type revealed that about 3.57% of cells were considered to be abnormal NK cells which account for all nuclear cells and 79% of the lymphocytes. The expression of CD7 and cytoplasin were attenuated. There was no expression of CD16, CD11b, CD8, and CD57. The positive ratio of Ki67 was 28.8%. We performed serologic tests for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) which turned out to be positive, and the titer of EBV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was >1.0 × 107 (normal range, <5.0 × 102). Splenic pathology supported splenic rupture evidence. The structure of the splenic tissue was discernible, the splenic corpuscle atrophied and the splenic pulp contained a large number of tissue cells proliferating and devouring mature red blood cells, lymphocytes, and cell debris. The spleen showed diffuse lymphoid cell infiltration, which were T cells (Fig. 2). Immnunohistochemical examination staining of clusters of CD56(+), GrB(+), TIA-1(+), CD2(+), CD3(part+), CD5(−), CD7(+), CD43(+), CD4(−), CD8(−), TdT(−), CD20(−), CD79α(−), PAX-5(−), CD34(−), CD117(−), MPO(−), CD99(−), CD123(−), LCA(+), CD68(−), CD163(−), Mum-1(−), κ(−), λ(−), and Ki-67(40%). Molecular identification: EBER CISH (+). On the basis of these findings, we diagnosed the case as invasive NK/T-cell lymphoma and HLH. Despite immunosuppressive therapy with dexamethasone (10 mg/day), and etoposide (270 mg/week) in combination with rituximab (370 mg/m2 weekly), the patient's clinical symptoms continued to deteriorate, and she died on the 18th day postoperation due to multiorgan failure.

Figure 1.

(A) Bone marrow aspiration showed evidence of hemophagocytosis. Macrophage engulfing erythrocytes, platelets, and neutrophils are noted (arrow); original magnification ×400. (B) Atypical lymphocytes (arrow) in bone marrow (×400).

Figure 2.

Hemotoxylin and eosin stain of splenic pulp biopsy with hemophagocytosis. (A) There are a large number of lymphocytic infiltration in splenic (×200). (B) The splenic pulp has a lot of tissue cells proliferating and devouring mature red blood cells, lymphocytes, and cell debris (×400).

Ethical approval of this study was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Tongji Hospital (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's husband for the publication of this case report.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges encountered in the management of HLH in a pregnant woman. Initially, our patient presented with fever, splenomegaly, pancytopenia in peripheral blood (hemoglobin <90 g/L, neutrophils <1 × 109/L, and platelets <100 × 109/L), hemophagocytosis in bone marrow and spleen, and ferritin >500 μg/L. These fulfilled 5 out of 8 criteria set out in a 2004 HLH trial,[2] which indicated a diagnosis of HLH. However, there are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for pregnancy-related HLH, because the 1st criteria defined in the 1990s were based on pediatric manifestations from the HLH-94 study and expert opinions changed following the subsequent HLH-2004 study.[2,3,5] In spite of its limitations, the HLH-2004 criteria are still widely accepted as a substitute definition. Since 5 criteria matched and the potential for malignancy was high, this case was diagnosed as malignancy-associated HLH (M-HLH).

Besides HLH, other common obstetric emergencies should also be considered. The presence of fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes exclusive to pregnancy naturally raise the suspicions of HELLP syndrome, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, or even sepsis.[6–8] Although similar to clinicopathological features of HLH, these aforementioned conditions usually improve within several days after delivery of the baby but HLH may have a progressive course.

HLH can be classified according to the underlying etiology into either primary or secondary.[2] Given the patient's medical history, secondary HLH was most likely. Primary HLH often occurs during infancy and early childhood, and it is associated with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern in most cases.[9] Secondary HLH generally occurs in older children and adults who do not have any known genetic causes or family history. The acquired form is usually secondary to infections, autoimmune diseases, or drugs as well as a wide spectrum of malignancies.[3]

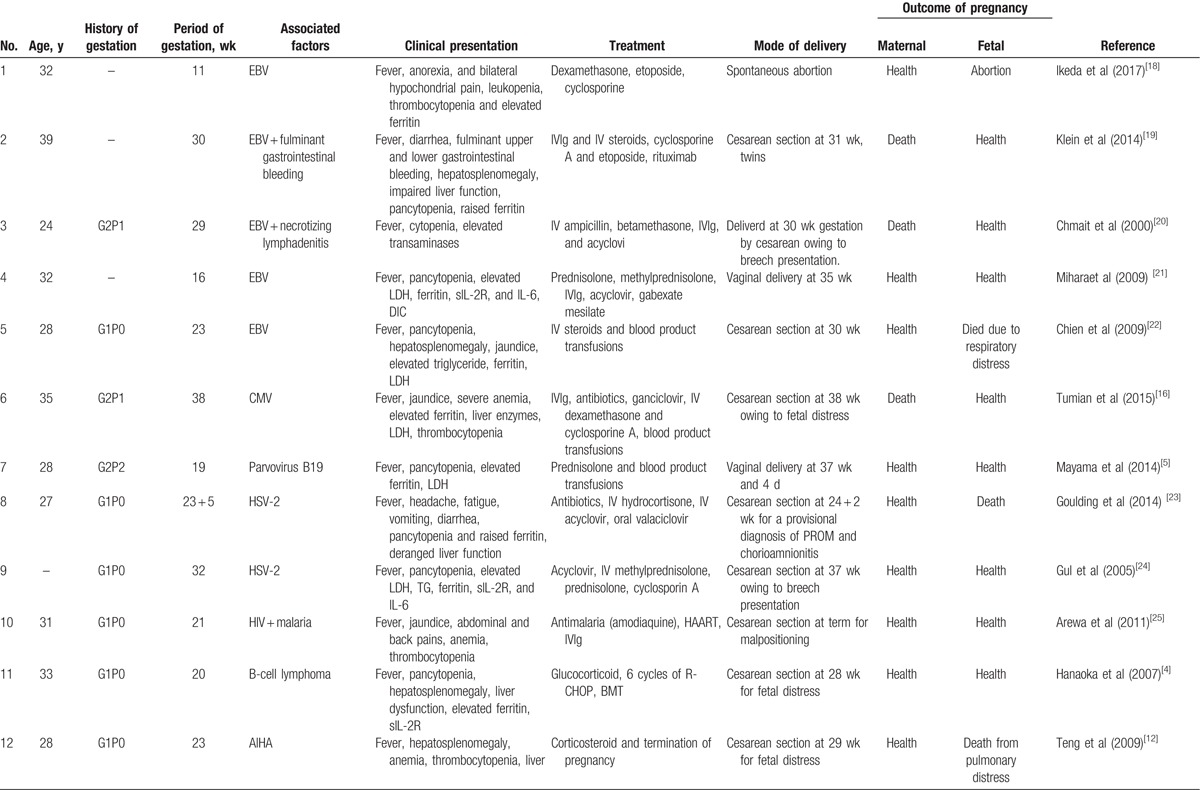

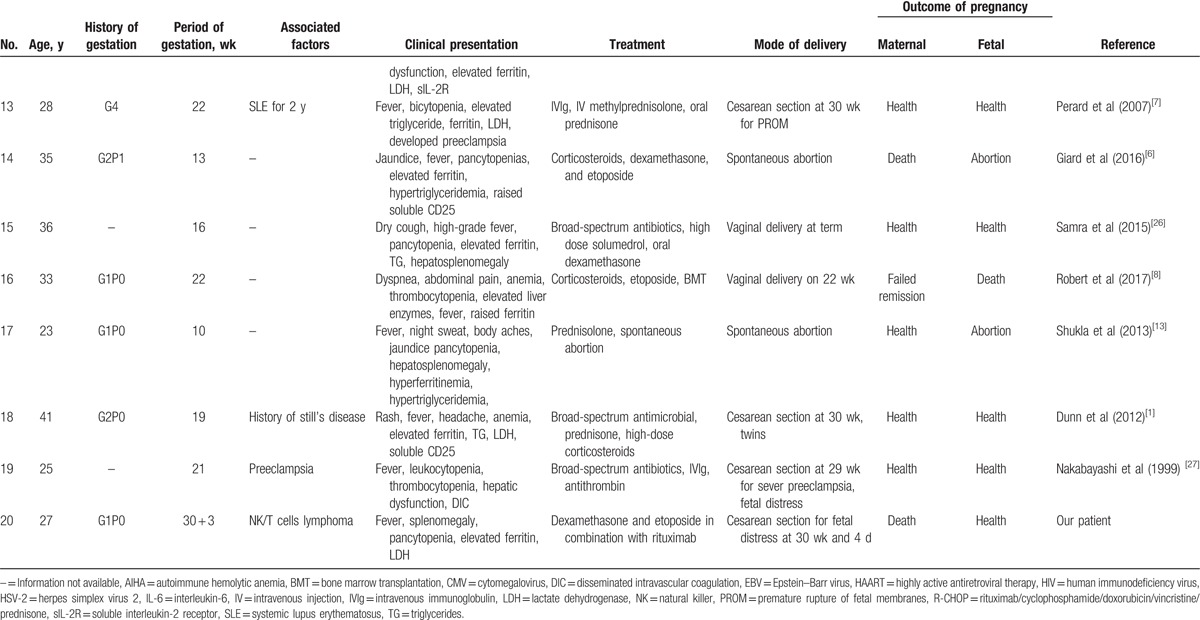

We carried a survey about pregnancy-related HLH from 1991 to 2017. Nineteen cases of HLH diagnosed during pregnancy have been described in the literature (Table 1 ). Ten patients had HLH associated with infections (including EBV, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus-2, human immunodeficiency virus, and parvovirus B19), 2 patients were secondary to autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hemolytic anemia), and 6 patients had unknown etiology which may be related with pregnancy while only 1 patient had HLH associated with malignancies (B-cell lymphoma). We found that infections might be a common predisposing factor in pregnancy-associated HLH. Many researchers reported that the most common tumor types triggering HLH are hematological neoplasms (93.7%) with T- or NK-cell lymphoma (35.2%), followed by B-cell lymphoma (31.8%) in nonpregnant population.[10] Our investigation yielded similar results supporting that B-cell lymphoma and NK/T-cell lymphoma were highly occurring malignancies in pregnancy-related HLH. However, epidemiological data on HLH in pregnancy are scarce due to its low incidence and insufficient knowledge. There is a need for more in-depth data to provide more insight.

Table 1.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy.

Table 1 (Continued).

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy.

The clinical course of M-HLH is aggressive.[11] The survival data have shown that nearly 56% to 70% patients have an overall survival of 36 to 230 days, and the 3-year survival of M-HLH patients is 18% to 55%.[10] In a Japanese study, the 5-year overall survival rate in HLH patients with B-cell lymphoma is only 48%, and it is merely 12% in NK/T-cell lymphoma.[11] One article reported an M-HLH during pregnancy where the mother delivered a healthy baby at 28 weeks of gestation. Through rituximab /cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine /prednisone chemotherapy and autologous peripheral-blood stem cell transplantation. She is currently in complete remission. However, the patient in our case did not acquire remission in spite of positive treatment admission.

The pathophysiology of HLH is not completely understood, especially its relation to pregnancy.[12] Hyperinflammation syndrome is believed to be responsible for HLH.[3] In pregnancy, the immature placenta releases trophoblastic debris into maternal circulation. This fetomaternal trafficking might induce a profound systemic inflammatory response leading to a cytokine storm.[13] Osugi et al[14] theorized that elevated Th1/Th2 in pregnancy may activate macrophages and lead to hemophagoctyosis. In addition, malignancies or infections, such as viruses, fungi, or bacteria, are also the major triggers in contributing to the secretion of excessive cytokines and the development of HLH.[9,15] Therefore, suppression of the overwhelming, life-threatening inflammatory process is necessary in conjunction with treatment of the underlying cause such as infection or malignancy.

Unfortunately, there is no consensus in treatment guidelines for pregnancy-related HLH,[16] particularly pregnancy associated with M-HLH. Therefore, treatment decisions are usually based on clinical experience, expert opinions, and clinical manifestations. The major drugs employed including high-dose steroids, etoposide, cyclosporine A, and intravenous immunoglobulin. They help in controlling hyperinflammation and hypercytokine response according to the protocols of HLH-2004.[2] Rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone and stem cell transplantation have revolutionized treatment alternatives and resulted in long-term survival in M-HLH.[9] From Table 1 we can see, almost all patients receiving high-dose corticosteroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulin. At the same time, active antiinfection drugs and blood transfusion can be supplemented according to the situation. In severe conditions, etoposide is also used to control the disease rapidly and reduce the fatality rate. However, its teratogenetic potential[17] causes further controversy, especially when termination of pregnancy might be preferred ahead of its administration.

It has consistently been demonstrated that preterm delivery, as opposed to fetal exposure to chemotherapy, highly predicts neurocognitive deficiency in children born to mothers receiving chemotherapy therapy during pregnancy.[17] Fetal survival rate associated with premature gestational age at birth is highly dependent on maternal condition during pregnancy. In Table 1 , there are three patients managed during the first trimester. After active treatment with no improvement, they elected to terminate their pregnancies. Twelve patients were treated during the second trimester. Through rapid diagnosis and effective steroidal treatment, 2 of the 12 continued their respective pregnancies safely to term and had healthy babies. Although 6 of 12 were unable carry to term, they also delivered premature but otherwise healthy neonates. Unfortunately, the remaining 4 had preterm delivery and lost their babies due to the deteriorating condition of the mother or fetus. Of the 5 patients recruited at their 3rd trimester, 2 carried to term and 3 had premature deliveries. They all had healthy babies.

Hence, the decision to terminate pregnancy is dependent on maternal condition, fetal gestational age, and disease-related factors, of which the most influential is the trimester at diagnosis, the cancer staging, aggressiveness of the disease, and coexisting life-threatening symptoms.[17] In 1st trimester, it is unlikely to sustain a pregnancy because the maternal condition tends to be more serious. In order to ensure the safety of the mother, they typically opt to terminate pregnancy. To patients presenting at 3rd trimester, the fetal survival rate is relatively higher. They usually choose immediate termination of pregnancy to ensure the safety of mother and fetus. In patients presenting at 2nd trimester, the decision is trickier. However, early diagnosis and prompt management will ensure optimistic outcomes.

In conclusion, we initially reported a rare case of NK/T cells lymphoma during pregnancy associated with HLH. We recommend that HLH be considered as differential diagnosis in a pregnant patient complaining of persistent fever, cytopenia, or declining clinical condition despite delivery of the baby. Secondary causes of HLH should also be explored thoroughly. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential and fetal outcomes should also be considered. The decision to terminate a pregnancy and initiate chemotherapy during pregnancy with M-HLH needs to be further investigated in a larger cohort.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the grants from the National Science Foundation of China (41671497), the National Science and Technology Pillar program of China during the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan Period (Grant No. 2016YFC1000405), and General item of Health and Family Planning Commission of Hubei Province (WJ2015MB001) for the support.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: EBV = Epstein–Barr virus, Hb = hemoglobin, HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, NK = natural killer.

LF and SW contributed equally to this work.

Funding/support: This work was sponsored by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (41671497), the National Science and Technology Pillar program of China during the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan Period (Grant No. 2016YFC1000405), and General item of Health and Family Planning Commission of Hubei Province (WJ2015MB001).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Dunn T, Cho M, Medeiros B, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pregnancy: a case report and review of treatment options. Hematology 2012;17:325–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes – an update. Blood Rev 2014;28:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hanaoka M, Tsukimori K, et al. B-cell lymphoma during pregnancy associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and placental involvement. Clin Lymphoma Myelom 2007;7:486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mayama M, Yoshihara M, Kokabu T, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with a parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:438–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Giard JM, Decker KA, Lai JC, et al. Acute liver failure secondary to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis during pregnancy. ACG Case Rep J 2016;3:e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Perard L, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Limal N, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in a pregnant patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, complicated with preeclampsia and cerebral hemorrhage. Ann Hematol 2007;86:541–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kerley RN, Kelly RM, Cahill MR, Kenny LC. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting as HELLP syndrome: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017: bcr2017219516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tamamyan GN, Kantarjian HM, Ning J, et al. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: Relation to hemophagocytosis, characteristics, and outcomes. Cancer 2016;122:2857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014;383:1503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hongluan W, Lixia X, Weiping T, et al. A systematic review of malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis that needs more attentions. Oncotarget 2017;8:59977–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Teng CL, Hwang GY, Lee BJ, et al. Pregnancy-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis combined with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Chin Med Assoc 2009;72:156–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shukla A, Kaur A, Hira HS. Pregnancy induced haemophagocytic syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2013;63:203–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Osugi Y, Hara J, Tagawa S, et al. Cytokine production regulating Th1 and Th2 cytokines in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 1997;89:4100–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xing Y, Yang J, Lian G, et al. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and extra-nodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma in an 18-year-old girl: a case report. Medicine 2017;96:e6845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tumian NR, Wong CL. Pregnancy-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with cytomegalovirus infection: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2015;54:432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pinnix CC, Andraos TY, Milgrom S, et al. The management of lymphoma in the setting of pregnancy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2017;12:251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ikeda M, Oba R, Yoshiki Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis during pregnancy. Rinsho Ketsueki 2017;58:216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Klein S, Schmidt C, La Rosee P, et al. Fulminant gastrointestinal bleeding caused by EBV-triggered hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: report of a case. Z Gastroenterol 2014;52:354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chmait RH, Meimin DL, Koo CH, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:1022–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mihara H, Kato Y, Tokura Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome during mid-term pregnancy successfully treated with combined methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulin. Rinsho Ketsueki 1999;40:1258–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chien CT, Lee FJ, Luk HN, et al. Anesthetic management for cesarean delivery in a parturient with exacerbated hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth 2009;18:413–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Goulding EA, Barnden KR. Disseminated herpes simplex virus manifesting as pyrexia and cervicitis and leading to reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;180:198–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gul A, Cebeci A, Erol O, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of 13q-syndrome in a fetus with Dandy-Walker malformation. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1227–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Arewa OP, Ajadi AA. Human immunodeficiency virus associated with haemophagocytic syndrome in pregnancy: a case report. West Afr J Med 2011;30:66–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Samra B, Yasmin M, Arnaout S, et al. Idiopathic hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis during pregnancy treated with steroids. Hematol Rep 2015;7:6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nakabayashi M, Adachi T, Izuchi S, et al. Association of hypercytokinemia in the development of severe preeclampsia in a case of hemophagocytic syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost 1999;25:467–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]