Abstract

Background:

Chronic pain is a major public health problem and 30% to 45% of sufferers experience severe depression. Acupuncture is often used to treat both depression and a range of pain disorders. We aim to conduct a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture for patients experiencing chronic pain with depression.

Methods:

To identify relevant RCTs, the following databases will be searched electronically from their inception to July 1, 2017: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Chinese medical databases, and others. Manual retrieval will also be conducted. RCTs that evaluated acupuncture as the sole or adjunct treatment for patients with chronic pain and depression will be included. The primary outcomes will be based on a visual analog pain measurement scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale. The secondary outcomes will include scores on a numerical rating scale, verbal rating scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The study selection, data extraction, and study quality evaluation will be performed independently by 2 researchers. If the data permit, meta-analysis will be performed using RevMan V5.3 statistical software. If the data are not appropriate for meta-analysis, descriptive analysis or subgroup analysis will be conducted. The methodological quality of the included trials will be assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria and the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture checklist.

Results:

This study will provide a high-quality synthesis of current evidence of acupuncture for chronic pain with depression from several scales including visual analog pain measurement scale, the Hamilton Depression Scale, a numerical rating scale, verbal rating scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Conclusion:

The conclusion of our study will provide updated evidence to judge whether acupuncture is an effective intervention for patients suffered from chronic pain with depression.

Keywords: acupuncture, chronic pain, depression, protocol, systematic review

1. Introduction

1.1. Description of the condition

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as an unpleasant subjective feeling and emotional experience associated with tissue damage or potential tissue damage, which is a combination of physical, psychological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social factors that interact with each other.[1,2] The IASP defines chronic pain as persistent or intermittent pain for more than 3 months.

Pain and depression are 2 of the most critical public health issues facing health care providers today. Chronic pain is predicted to affect up to 10% to 33.3% of adults worldwide.[3] Data from a European population-based study indicate that 19% of individuals suffered from chronic pain [10-point numerical rating scale (NRS) >5], 66% of these had moderate pain (NRS 5–7), and 34% had severe pain (NRS 8–10).[4] Ohayon and Stingl [5] found a 2011 chronic pain prevalence of 24.9% in Germany. Similarly, it is estimated that depression affects approximately 350 million people globally and 16.2% of Americans at some point in their lifetime.[6,7] Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and is a significant contributor to increased medical costs and economic burden.[6,8] Unfortunately, pain and depression frequently coexist and this comorbidity is associated with a greater burden to the individual and society than either condition alone.[9,10] Chronic pain decreases patients’ quality of life, which can affect their mood and lead to depression. The occurrence and development of chronic pain are closely related to psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, mood, and stress.[11,12] Statistics show that 30% to 45% of patients with chronic pain suffer from severe depression.[13] One epidemiological survey found that the incidence of depression in patients with chronic pain was 52% and that 65% of patients with depression have symptoms of pain.[14]

Depression and pain share biological pathways and neurotransmitters, which has implications for their concurrent treatment. The pain experience involves activation of multiple brain regions and can lead to mental illness and impairments in quality of life. Negative emotional experiences can produce sensations of pain in the absence of tissue damage; this can aggravate pain or reduce therapeutic effects. Mindfulness-based interventions have recently been shown to be effective for the treatment of chronic pain, and have small to moderate effects on pain and depression. Therefore, the presence of emotional disorders can seriously hinder the treatment of chronic pain; conversely, clinical treatment can relieve chronic pain through the management and regulation of emotion. Pain and depression are often treated individually and pharmacological treatment can produce side effects; therefore, the use of holistic therapy could enhance treatment outcomes.[15]

1.2. Description of the intervention

As an ancient therapeutic modality and an important part of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), acupuncture has become a widely recognized complementary and alternative therapy in clinical practice. Acupuncture uses very fine needles to stimulate specified acupuncture points. If it is performed properly by qualified acupuncturists, acupuncture is a nontoxic treatment with an excellent safety profile (serious adverse events are rare).[16,17] Acupuncture is used to treat a range of conditions, such as migraine,[18] tonsillectomy pain,[19] neck pain,[20] knee pain,[21] sciatica,[22] and depression.[23–25]

A meta-analysis of data from nearly 18,000 randomized participants in 25 high-quality trials indicated that acupuncture is an effective treatment option for patients with back and neck pain, osteoarthritis, chronic headache, and shoulder pain.[23] One randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that acupuncture significantly reduced depression at 3 months compared with usual care.[26] Acupuncture can also reduce the side effects of antidepressant treatment.[27] The evidence of these studies suggests that acupuncture is also an effective add-on treatment for patients with depression.[23–28] One RCT to evaluate acupuncture for depression in cancer patients showed that acupuncture significantly reduced malignant-related depression and improved patient quality of life.[29]

1.3. How the intervention might work?

According to TCM theory, pain is not only a sign of discomfort but also an integral part of a particular disease or physiological malfunction. Acupuncture affects the neurovascular network and can radically change the impedances of meridians or neurovascular bundles. Therefore, both the match and mismatch of acupuncture meridian impedances with the pain source or brain impedance can reduce pain symptoms.[30] Acupuncture provides overall coordination, helping to achieve the state of relative equilibrium of body and mind. In addition, some trials have investigated that acupuncture can improve depressive disorders caused by cancer or post-stroke and can act on depression by protecting nerve cells in the hippocampus.[31–33] Therefore, not only where the pain is should be considered when selecting the acupoints to treat chronic pain but also the distal acupoints from TCM syndrome differentiation, which attribute depression to liver qi stagnation.[34] Currently, acupuncture is a popular treatment for patients with chronic pain and depression.[23,25–30,35]

1.4. Why it is important to conduct this review?

Depression associated with chronic pain often requires long-term treatment. Compared with pharmacological therapies, acupuncture has few side effects and can significantly reduce pain and depression. There have been more than 10 systematic reviews of acupuncture for chronic pain since 2010.[36–46] Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews of the use of acupuncture for chronic pain with depression. Hence, a comprehensive review of acupuncture treatment of chronic pain with depression is needed and could help patients, practitioners, and health policy-makers.

1.5. Objectives

This review aims to systematically evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture intervention for chronic pain with depression.

2. Methods and analysis

2.1. Study registration

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO 2016 (registration number: CRD42016041691). This protocol report was structured according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement guidelines.[47] The review will be implemented according to the PRISMA statement guidelines.[48]

2.2. Inclusion criteria for study selection

2.2.1. Type of study

All RCTs of acupuncture therapy for chronic pain with depression will be included in the review. Crossover studies that compared acupuncture with either sham acupuncture or non-acupuncture interventions in patients with chronic pain and depression will also be included. Nonrandomized clinical studies, cluster randomized trials, and quasi-randomized trials will be excluded.

2.2.2. Type of participant

Patients diagnosed with chronic pain and depression will be included. There will be no limits on the age, sex, and source of cases. Patients experiencing only chronic pain or only depression will be excluded.

2.2.3. Type of intervention

Acupuncture is defined as needle stimulation of acupoints and includes body acupuncture, scalp acupuncture, manual acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, electroacupuncture, fire needling, and plum blossom needling. The review will exclude studies that used other stimulation methods, such as acupressure, moxibustion, laser acupuncture, pharmacoacupuncture, dry needling, or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Sham acupuncture includes sham acupuncture at selected acupoints, sham acupuncture at non-acupoints, needling at inactive acupoints, nonpenetrating sham acupuncture, and pseudo-acupuncture interventions.[49]

We will also include trials that compared acupuncture and another typical treatment with other typical treatments alone. Control interventions will include sham/placebo acupuncture, no treatment, waiting list membership, and conventional therapies (e.g., usual care, analgesics, manual therapy).

2.2.4. Type of outcome measure

2.2.4.1. Primary outcomes

The primary outcome will be measured using a visual analog scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD).

2.2.4.2. Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes will be measured using a NRS, a verbal rating scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

2.3. Search methods for identification of studies

2.3.1. Electronic searches

Following the core, standard, ideal search (COSI) model,[50] the following electronic databases will be searched from inception to July 1, 2017: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.[51] We will also search the following Chinese medical databases: the China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database, the Chongqing VIP Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database, and the Wanfang Database. We will also retrieve unpublished protocols and summary results through a search of the clinical trial registry at https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

2.3.2. Searching other resources

The reference lists of potentially eligible studies and relevant systematic reviews will be manually retrieved and examined to locate additional trials. Relevant conference proceedings will also be searched to identify studies. We will also search OpenGrey.eu for potential gray literature. In addition, we plan to search relevant trial protocols using the WHO International Clinical Trial Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing and recently completed studies. We will also search conference proceedings related to the topic.

2.3.3. Search strategy

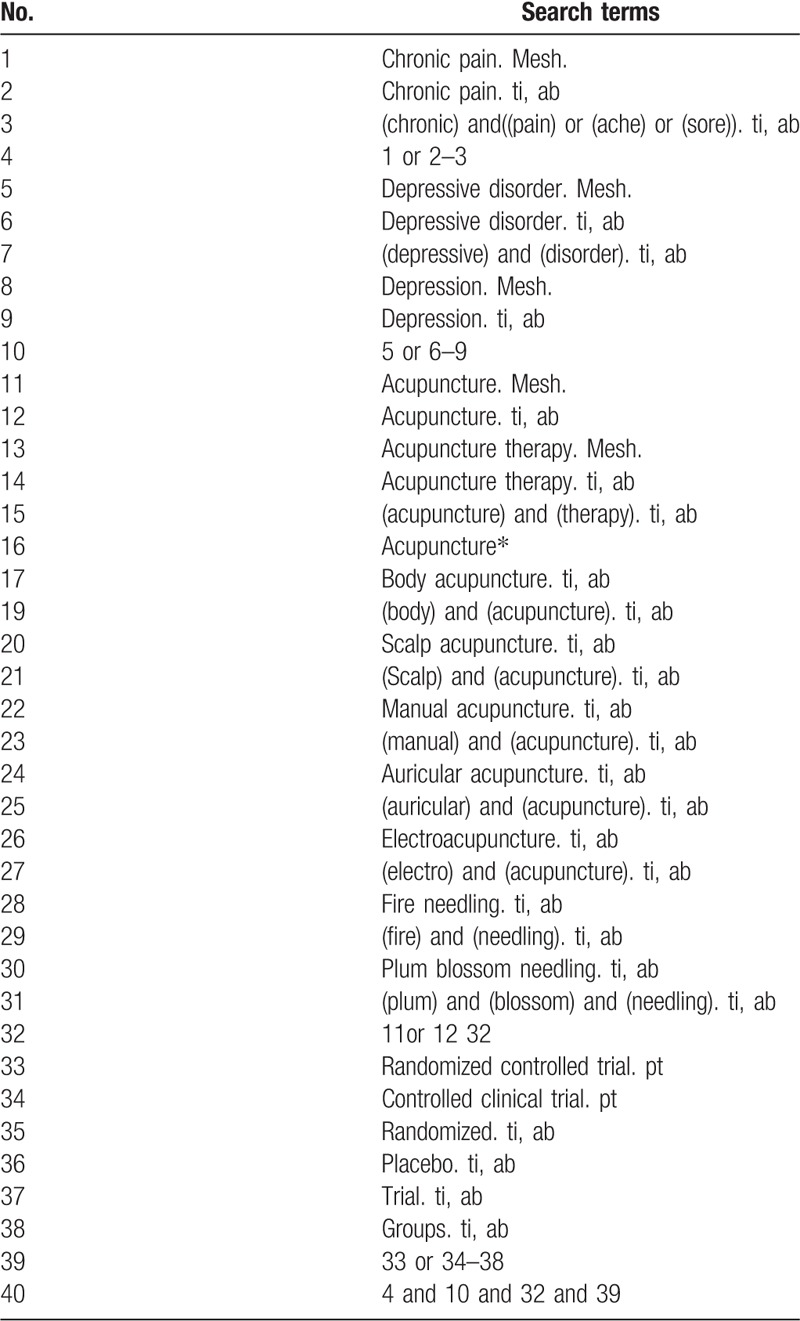

The following search keywords will be used: RCT (controlled clinical trial); acupuncture (e.g., “acupuncture” or “body acupuncture” or “scalp acupuncture” or “manual acupuncture” or “auricular acupuncture”, “electroacupuncture” or “fire needling” and “plum blossom acupuncture”); chronic pain (e.g., “chronic pain” or “chronic ache” or “chronic sore” and “chronic illness”); and depression (e.g., “depression” or “mild mental disorders” or “dysthymia disorders” or “depressive disorder” or “mental illness”). For the other databases, these English search terms will be accurately translated. The search strategies for PubMed are summarized in Table 1; we will modify these strategies for other databases.

Table 1.

Search strategy used for PubMed database.

2.4. Data collection and analysis

2.4.1. Selection of studies

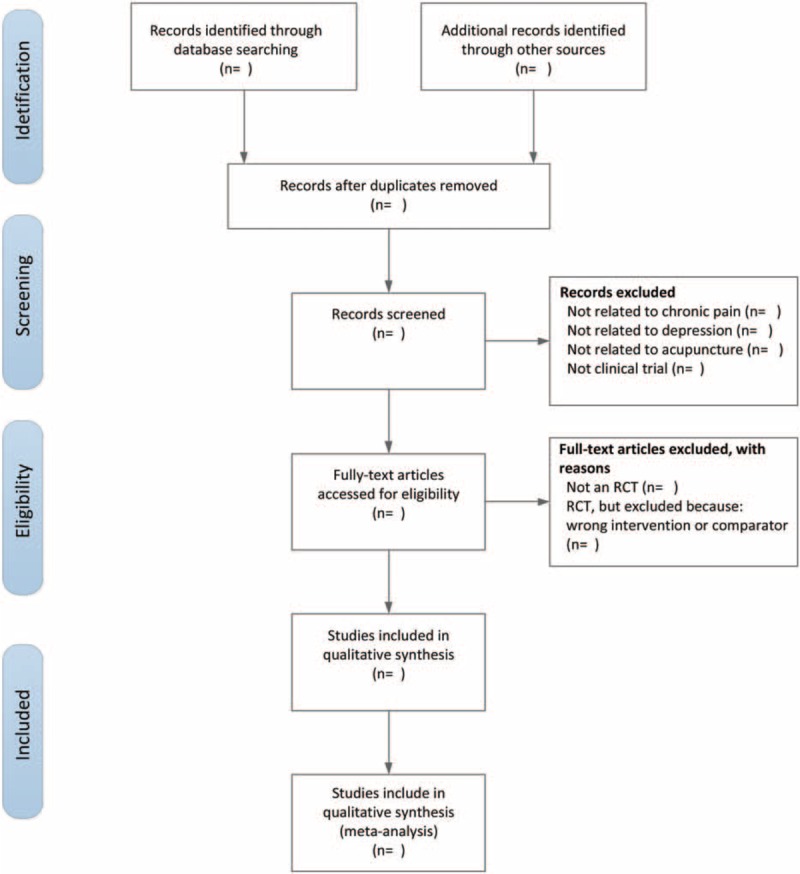

Two reviewers will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all searched studies and eliminate duplicated or irrelevant papers. The full text of the eligible studies will be read. When the 2 reviewers cannot agree on the selection process through consultations, the third reviewer will ultimately make the decision. The primary selection process is shown in a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow chart of the selection process.

2.4.2. Data extraction and management

The following data will be extracted from all eligible studies by 2 independent reviewers and entered into a data extraction sheet: reference ID, first author, publication year, country, participant characteristics (e.g., average age, gender), type of intervention, type of control intervention, sample size of each intervention group, randomization, allocation concealment and blinding methods, outcome measures, main outcomes and adverse effects, duration of follow-up, type and source of financial support, and the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) checklist. In cases of insufficient data, we will contact the authors for more information. When a consensus on the data extraction cannot be obtained through consultations, the third author will make a decision.

2.4.3. Assessment of risk of bias and reporting of study quality

Two review authors will independently evaluate the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk-of-bias assessment method and complete the STRICTA checklist for the included studies.[52] The following domains will be accessed for risk of bias: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other issues. Trials will be assessed and categorized according to 3 levels: unclear risk, low risk, and high risk. Any discrepancies will be resolved by discussion and consensus with the third author. When a consensus on risk assessment cannot be reached by discussion, the third author will make the decision.

2.4.4. Measures of treatment effect

Mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) will be used to analyze continuous data. Other forms of data will be changed into MD values. Standardized MDs with 95% CIs will be used if different scales were used to measure a particular outcome variable. Dichotomous data will be analyzed using the risk ratio with 95% CIs. If significant heterogeneity is detected, a random-effects model will be used.

2.4.5. Unit of analysis issues

We will focus on patients in randomized studies. If more than one acupuncture arm is used, we will conduct separate multiple meta-analyses for each treatment arm. If multiple non-acupuncture control groups are included, we will combine all control group outcomes and carry out pooled analyses of the control groups against the intervention group.

2.4.6. Management of missing data

If there are missing data for the primary results, we will contact the corresponding authors to request the missing data. If the missing data cannot be obtained, the analysis will rely on the available data.

2.4.7. Assessment of heterogeneity

If possible, we will use fixed-effects or random-effects meta-analyses. According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, heterogeneity can be assessed in the following ways: a visual check of the forest plot, a heterogeneity χ2 test, and Higgins’ I2 statistic.[53,54] We will use Review Manager software (RevManV.5.3.5 for Windows; the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) to obtain forest plots and heterogeneity test results. A fixed-effects model will be used to pool the data if the P value is larger than .10 and the I2 value is less than 50%. Otherwise, a random-effects model will be used. If the heterogeneity remains significant, subgroup analyses will be conducted. If a quantitative summary of the data still cannot be obtained, a narrative summary will be used to discuss the findings.

2.4.8. Assessment of reporting biases

If more than 10 trials are included, funnel plots will be used to assess reporting biases. If funnel plot asymmetry is detected, we will try to analyze the reasons for this.

2.4.9. Data synthesis

We will use RevMan for all statistical analyses. We will use either a fixed-effects model or a random-effects model, depending on the heterogeneity levels of the included studies. If considerable heterogeneity is observed, a random-effects model with 95% CIs will be used to analyze pooled effect estimates. If meaningful heterogeneity is identified that cannot be explained by any additional assessment, such as subgroup analysis, we will not attempt to perform a meta-analysis. If necessary, subgroup analysis will be performed with careful consideration of each subgroup.

2.4.10. Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis will be conducted based on the type of control intervention and different outcomes.

2.4.11. Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis will be performed according to the following criteria: sample size, heterogeneity qualities, and statistical model (random-effects or fixed-effects model).

3. Discussion

This study will be the first systematic review of the effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic pain with depression. The review will be divided into 4 sections: identification, study inclusion, data extraction, and data synthesis. The resulting evidence will provide important information that could benefit patients, practitioners, health policy-makers, and acupuncture practitioners.

Acknowledgment

We thank Diane Williams, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, COSI = core, Development and Evaluation, GRADE = the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, HADS = the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HAMD = Hamilton Depression Scale, IASP = International Association for the Study of Pain, MD = mean difference, NRS = numerical rating scale, PRISMA-P = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols, RCTs = randomized controlled trials, standard and ideal search, STRICTA = the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture, TCM = traditional Chinese medicine, WHO = World Health Organization.

Authorship: ZYY and LZ conceived the study. XZX, TX, XW, MYZ, ZWW, and YTZ drafted the protocol. The search strategy was developed and will be conducted by ZYY and TX. MYZ and XW will obtain copies of the studies and JRD and ZYY will select the studies to be included. LZ will act as an arbiter in the study selection stage. ZYY, TX, and XW will extract data from the studies. ZYY and XW will enter data into RevMan. ZYY, TX, and LZ will conduct the analyses. ZYY, TX, XW, MYZ, ZWW, and YL will interpret the analyses. ZYY, TX, XW, MYZ, ZWW, and SYZ will draft the final review and ZYY and LZ will update the review.

Funding/support: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81473603) and National Natural Foundation for Excellent Youth Fund (81722050), the Project of Youth Fund of Sichuan Province (2016JQ0013) (all awarded to Ling Zhao).

Ethical approval for the study is not necessary because individuals cannot be identified. The protocol will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and/or presented at an appropriate conference. This systematic review will assess the current evidence for the efficacy of acupuncture treatment for patients suffering from chronic pain with depression.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Trial registration number: PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016041691

References

- [1].Merskey H. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Pain 1995;(Suppl 3): 39–68, 210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Peicheng H. Clinical Psychology. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Levenson JL. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine: Psychiatric Care of the Medically Ill. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ohayon MM, Stingl JC. Prevalence and comorbidity of chronic pain in the German general population. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:444–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].WHO. Depression Factsheet. 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/index.html. Accessed February, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mossey JM, Gallagher RM. The longitudinal occurrence and impact of comorbid chronic pain and chronic depression over two years in continuing care retirement community residents. Pain Med 2004;5:335–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med 2006;68:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Castrén E. Is mood chemistry? Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6:241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S, et al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the world mental health surveys. Pain 2007;129:332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Alschuler KN, Theisen-Goodvich ME, Haig AJ, et al. A comparison of the relationship between depression, perceived disability, and physical performance in persons with chronic pain acupuncture and counselling for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2008;12:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, et al. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2433–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, et al. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med 2004;66:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Macpherson H, Scullion A, Thomas KJ, et al. Patient reports of adverse events associated with acupuncture treatment: a prospective national survey. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;8:515–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Witt CM, Pach D, Brinkhaus B, et al. Safety of acupuncture: results of a prospective observational study with 229,230 patients and introduction of a medical information and consent form. Forsch Komplementmed 2009;16:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhao L, Chen J, Li Y, et al. The long-term effect of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ochi JW. Acupuncture instead of codeine for tonsillectomy pain in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:2058–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Limin F, Jutzu L, Wenshou W. Randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for neck pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, et al. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised trial. Lancet 2005;366:136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Qin Z, Liu X, Wu J, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for treating sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:425108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1444–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bosch P, Noort MVD, Staudte H, et al. Schizophrenia and depression: a systematic review of the effectiveness and the working mechanisms behind acupuncture. Explore 2015;11:281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sniezek DP, Siddiqui IJ. Acupuncture for treating anxiety and depression in women: a clinical systematic review. Med Acupunct 2013;25:164–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Macpherson H, Richmond S, Bland M, et al. Acupuncture and counselling for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Plos Med 2013;10:e1001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu J, Yeung AS, Schnyer R, et al. Acupuncture for depression: a review of clinical applications. Can J Psychiatry 2012;57:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yuanyu C, Wanyu L, Szuniab Y, et al. The benefit of combined acupuncture and antidepressant medication for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2015;176:106–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Feng Y, Wang XY, Li S, et al. Clinical research of acupuncture on malignant tumor patients for improving depression and sleep quality. J Tradit Chin Med 2011;31:199–202. 2011-01-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chang S. The meridian system and mechanism of acupuncture: a comparative review. Part 2: mechanism of acupuncture analgesia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2013;52:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Bruner D, et al. Electroacupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: a randomized trial. Cancer 2014;120:3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Man SC, Hung BHB, Ng RMK, et al. A pilot controlled trial of a combination of dense cranial electroacupuncture stimulation and body acupuncture for post-stroke depression. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu S, Li S, Shen X, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on depression in a rat model. Acupunct Electrother Res 2011;36:259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhu Z, Ding Z. Acupuncture and Moxibustion treatment of anxiety neurosis and study on characteristics of acupoint selection. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2008;28:545–8. (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weiwei T, Xi L, Bai C, et al. Practice of traditional Chinese medicine for psycho-behavioral intervention improves quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2015;6:39725–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang Q, Yue J, Golianu B, et al. Acupuncture for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e008027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Posadzki P, Zhang J, Lee MS, et al. Acupuncture for chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a systematic review. J Androl 2012;33:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yingchun Z, Waiyee C. Acupuncture for chronic nonspecific low back pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Eur J Integr Med 2015;7:94–107. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vickers A, Cronin A, Maschino A, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012;12:E1–0. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hopton A, Macpherson H. Acupuncture for chronic pain: is acupuncture more than an effective placebo? A systematic review of pooled data from meta-analyses. Pain Pract 2010;10:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Trigkilidas D. Acupuncture therapy for chronic lower back pain: a systematic review. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:595–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic pain: protocol of the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration. Trials 2010;11:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ezzo J, Berman B, Hadhazy VA, et al. Is acupuncture effective for the treatment of chronic pain? A systematic review. Pain 2000;86:217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Vickers AJ, Angel D, Cronin M, et al. Review article acupuncture for chronic pain individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2013;172:1444–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dalamagka M. Systematic review: acupuncture in chronic pain, low back pain and migraine. Pain & Relief 2015;4:195. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hutchinson AJP, Ball S, Andrews JCH, et al. The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Surg Res 2012;7:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;350:g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yongliang J, Leimiao Y, Yu W, et al. Assessments of different kinds of sham acupuncture applied in randomized controlled trials. J Acupunct Tuina Sci 2011;9:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bidwell S, Jensen M. Chapter 3: Using a Search Protocol to Identify Sources of Information: the COSI Model Etext on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Information Resources 2004. Available at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20060905/nichsr/ehta/chapter3.html#COSI. Accessed September 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bidwell S, Jensen MF. Etext on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Information Resources: Chapter 3: Using a Search Protocol to Identify Sources of Information: The COSI Model. [updated 14 June 2003]. National Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20060905/nichsr/ehta/chapter3.html. [Google Scholar]

- [52].John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Higgins JPT, Green S. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2008. 187–241. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochranehandbook.org. [Google Scholar]