Abstract

Background.

The aetiology of temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) is multifactorial, whereas occlusal disharmony is one of the predisposing factors. Researchers still discuss the relation between occlusion and TMD.

Objective.

The study aims to investigate the relation between static occlusal parameters and TMD clinical symptoms using T-Scan II analysis system.

Material and methods.

The sample consisted of 44 persons divided into the treatment group of 20 TMD patients and the control group of 24 subjects without TMD. The main task of T-Scan II computerized occlusal analysis system was to record every patient’s occlusion and estimate static occlusal parameters: centre of occlusal force, asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force and occlusion time. These results were compared between groups, data related to patients’ complaints and clinical symptoms. The analysis was carried out using Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-square tests.

Results.

Averages of the centre of occlusal force in TMD subjects were 6.55 ± 0.99 mm, in the control group – 5.88 ± 0.69 mm; the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force averages: 15.90 ± 2.71 and 12.93 ± 1.88; occlusion time: 0.281 ± 0.036 s and 0.236 ± 0.022 s, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between two groups but they were found in the centre of occlusal force and the asymmetry index in the two groups (p < 0.05).

Conclusions.

There exists a relation between complaints of patients with TMD and static occlusion parameters. Values of the centre of the occlusal force distance and the asymmetry index of occlusal force in TMD patients with pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) were significantly higher than in the control group.

Keywords: temporomandibular joint, temporomandibular joint disorders, centric occlusion

Abstract

OKLIUZIJOS RODIKLIŲ IR SMILKININIO APATINIO ŽANDIKAULIO SĄNARIO FUNKCIJOS SUTRIKIMŲ SIMPTOMŲ SĄSAJŲ VERTINIMAS

Santrauka

Įvadas. Smilkininio apatinio žandikaulio sąnario (SAŽS) sutrikimų kilmė yra polietiologinė. Viena iš priežasčių – netaisyklinga okliuzija. Tačiau ryšys tarp okliuzijos ir SAŽS sutrikimų iki šiol išlieka diskutuojamu mokslininkų klausimu. Darbo tikslas – ištirti ryšį tarp statinių okliuzijos parametrų ir SAŽS disfunkcijos klinikinių simptomų naudojant T–Scan II analizatorių (Tekscan, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Tyrimo medžiagos ir metodai. Tyrime dalyvavo 44 pacientai. Pirmąją grupę sudarė asmenys, turintys nusiskundimų dėl SAŽS, o antrąją grupę – sveiki žmonės. T–Scan II analizatoriumi kiekvieno paciento sukandimas įrašytas į centrinę okliuziją, po to vertinti gauti parametrai: okliuzinės jėgos centras, maksimalios okliuzinės jėgos asimetrijos indeksas, sukandimo laikas. Gauti rezultatai lyginti tarp tiriamųjų grupių, duomenys susieti su nusiskundimais ir klinikiniais simptomais. Statistinė analizė atlikta taikant Mano–Vitnio, Kruskalio–Valiso ir Chi kvadrato testus.

Rezultatai. Gautas okliuzinių jėgų centro vidurkis tiriamojoje grupėje – 6,55 ± 0,99 mm, kontrolinėje – 5,88 ± 0,69 mm. Maksimalios okliuzinės jėgos asimetrijos indekso vidurkis atitinkamai 15,90 ± 2,71 ir 12,93 ± 1,88, sukandimo laiko vidurkiai atitinkamai 0,281 ± 0,036 s ir 0,236 ± 0,022 s. Statistiškai reikšmingų skirtumų tarp tiriamųjų grupių nėra, o statistiškai patikimi okliuzinių jėgų centro ir asimetrijos indekso skirtumai tarp dviejų grupių (p < 0,05).

Išvados. Tyrimo metu nustatytas ryšys tarp pacientų, turinčių SAŽS nusiskundimų ir statinių okliuzijos parametrų. Okliuzinės jėgos centro nuotolis ir maksimalios okliuzinės jėgos asimetrijos indeksas patikimai susiję su pacientų jaučiamu skausmu bei statistiškai reikšmingai didesni, palyginti su kontroline grupe.

Raktažodžiai: smilkininis apatinio žandikaulio sąnarys, smilkininio apatinio žandikaulio sąnario sutrikimai, centrinė okliuzija

INTRODUCTION

During the recent decades controversial opinions have dominated the literature on the aetiology, diagnostics and treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) (1). According to the results of the study carried out by Luther (2007), from 7% to 84% of the world population (aged 3–74) suffer from these disorders (2). In 2013, the TMJ Association in the USA came to the conclusion that approximately 35 million of the US population are affected by the disorders of the temporomandibular joint and the masticatory muscles. An epidemiological study has shown that approximately 75% of adult population have at least one symptom related to TMD dysfunction and 30% – two or more symptoms (3). Patients tend to indicate different clinical symptoms: pain during mouth opening and chewing, crepitation, clicking in the area of the temporomandibular joint or ear, limited mandibular opening, morning stagnation, and sleep disorders (4, 5). Since it is difficult to identify a single main reason for the symptoms in the area of this joint (6), the aetiology of the disorders is polyetiological. However, the relationship between dental occlusion and TMDs is still a subject of debate by different researchers in the dental community. Back in 1993, there was a strong argument that the role of dental occlusion in the aetiology of TMDs was not important (7). According to the study results, in the cases of chronic pain in the temporomandibular joint area patients could be treated by physiotherapy (e.g., electromyographic biofeedback for muscle relaxation) rather than occlusal correction (8). Still there is no evidence if repetitive or extensive occlusal therapy can have a significant impact on TMDs (9). In addition, there is evidence that due to adaptation characteristics of the human articulatory system, morphological disorders in the temporomandibular joint are not an invariable consequence of occlusal disorders (10). According to Chinese researchers, occlusal interferences are directly related to pain in masticatory muscles and instability of mandibular condyle, which influences TMDs (11). To achieve static occlusion, posterior teeth should be in simultaneous contact, with equally distributed force on the dental arch (12). The most stable central occlusion occurs when the mandibular condyle is located in the mandibular fossa, slightly (~0.5 mm) glided forward and downward, from the apex of its front position, at the base of the articular tubercle of the temporal bone (13). Occlusal forces are concentrated and distributed evenly on the dental arches, whereas temporomandibular joints are affected only by a minor load (14). Adequate occlusal load depends on occlusal surfaces, tilting of each tooth, and the degree of tilt (15).

Articulating paper which is used for clinical testing of occlusion has drawbacks: the picture is two-dimensional and not adequate for evaluating the distribution of forces during occlusion (4) Digital analysis allows obtaining additional information about occlusion time, the centre of the occlusal force and the distribution of forces on both sides of the mandible. According to some authors, occlusion time is related with premature contacts and occlusion instability (6). Premature contacts can result in condyle displacement, which may potentially cause friction and increased intra-articular pressure on the TMJ. Both situations are harmful to the TMJ and contribute to the alteration of the structure of the TMJ. If the capacity of a subject to adapt to the situation is exceeded, the TMJ and disorders of the masticatory muscles may occur (16–18). Prolongation of occlusion time may also influence the pathological wear of occlusal surfaces (19). Digital occlusal analysis in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders may allow evaluating the relationship between occlusal factors and pathological conditions of the temporomandibular joint.

This kind of data may lead to a more precise diagnostics and selection of an adequate treatment plan. The null hypothesis is that changes in static occlusion parameters are related with TMD. The aim of this work is to analyse the relationship between static occlusal parameters and clinical symptoms of TMD by applying the T-Scan II analysis system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study was carried out at the Clinical Department of Dental and Maxillary Orthopaedics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania, in 2014. Permit No. BEC-OF-399 was issued by the Bioethics Centre at the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences for the purposes of this study. The study sample consisted of 44 patients: 32 female and 12 male. The patients were selected according to the following criteria: the orthognatic type of bite (Angle Class I), good oral hygiene, absence of periodontal disease and systemic inflammatory conditions, complete permanent dentition except for the third molars, no clinical signs of bruxism and tooth wear, absence of treatment on TMDs and orthognathic surgery. The study sample was subdivided into two groups of subjects. In the first group, people complained of TMDs, whereas those in the second (control) group were healthy subjects. The control group involved 24 people. In the treatment group, 20 patients suffered from pain or crepitation in the area of the temporomandibular joint, limited mouth opening, deviation, stagnation, and fatigue during extended periods of mouth opening, TMJ sounds (clicking). Based on complaints frequency characteristics, the patients were subdivided into groups. Their age was from 20 to 44; average age: 25.9 ± 0.8.

Equipment, procedure and statistical analysis

T-Scan II (Tekscan, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) is a digital system for occlusal analysis. It consists of a thin (100 µm) U-shaped pressure-sensitive gauge, a holder and a computer. A USB connector is used to connect the holder to the computer. This device of clinical diagnostics evaluates and visualizes occlusal contacts and their parameters during static or dynamic occlusion. The programme of this system involves the time and force analysis modes. The time analysis mode is used to visualize the distribution, sequence and time of occlusal contacts, whereas the force analysis mode is employed to identify the place, area, force and time of occlusion. The video material is available as 2D or 3D. The system also identifies the centre, trajectory and strength of occlusal force. It also allows analysing premature occlusal contacts during maximum intercuspation and dental contacts during side-to-side or forward movements of the lower jaw. Limitations of the T-Scan system are that it provides only a qualitative assessment of occlusal force, when a sensor is used more than once: sensitivity decreases or even disappears and increasingly fewer occlusal markings can be seen (20, 21). In addition, when forces are concentrated in a small area (e.g., a tooth cusp tip), the sensor may be damaged and, therefore, make an inaccurate recording of the occlusal contact or inaccurate artifacts in the produced images (22). Even if T-Scan sensors are as thin as possible (100 µm), hyperactivity of the masticatory muscles is detected when electromyograph is used at the time of occluding the sensor, which may lead to jaw diplacement and have a direct impact on tooth contact information and occlusal parameters (23).

Our study was conducted in the dental office. The aim of the study was explained to the patients and they gave their consent to participate in the study. The first part of the study involved each patient’s anamnesis and evaluation of their complaints. The muscles of TMJ were palpated using a bimanual technique during rest and mouth opening. Extraoral palpation was used for masseter and temporalis muscles (24, 25). Pain was detected during the palpation and movements of the lower mandible (6), also marked as positive when painful conditions persisted longer than three months (26). The severity of pain was assessed on the VAS (visual analogue scale for pain): 0 – no pain, 10 – worst possible pain (27, 28). Before the second part of the study, the mandible was manipulated to the centric relation by bimanual technique which was chosen according to its clinical significance and better repeatibility (29). A patient was also asked to swallow saliva and get into centric occlusion. A patient was seated comfortably on a dental chair and the head position was fixed with the Frankfurt horizontal plane paralleling the horizontal plane. When the patient was ready, the gauge was placed in his or her mouth; it transmitted the information on the bite force and time to the computer program in real time; thus the force was measured in intervals of up to 0.01 second. The gauge and the holder in the mouth were positioned along the line of the occlusal centre of the upper jaw. The procedure was repeated three times. The same examiner carried it out on all the study subjects. For data processing, one video was selected that captured full occlusal surface contact with occlusal force close to 100%.

In this study the centre of occlusal force is defined as the distance from the central line of the dental arch measured with accuracy of up to 0.01 mm. The asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force (AOF) is the difference of the occlusal force between the right and the left sides. It is calculated as follows: Max. AOF (%) = occlusal force of left side – occlusal force of right side/total occlusal force * 100%. Occlusion time is the time between the first dental contact and maximum intercuspation. It is measured by using the mode of force analysis, i.e., the graph of ‘‘force and time’’.

The study data were processed by the software IBM SPSS 22. The distribution of all the data was not normal (Shapiro-Wilk test p < 0.05), thus rank tests were applied for the comparison of quantitative values: Mann-Whitney, U, and Kruskal-Wallis tests. The results were presented by the average, standard deviation, or error. Qualitative values were compared by a chi–square test. ROC curves were employed to evaluate the diagnostic potential of occlusal parameters. The odds ratio was calculated to evaluate the relationship of the parameters with pain; the method of logistic regression was used. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

The values of the centre of the occlusal force, the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force, and occlusion time were identified for each patient in the sample. The minimum value of the centre of the occlusal force was 1, maximum – 19; the minimum value of the asymmetry index was 0.6, maximum – 41.1; the minimum occlusion time was 0.084, maximum – 0.695. A comparison of all occlusal parameters between the treatment group and the control group (Table 1) showed that the values of all the parameters were higher in the treatment than in the control group but these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Average values of occlusive parameters in the treatment group (patients with TMDs) and control group

| Occlusive parameters | Number of participants | Average | Standard deviation | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre of occlusive force (mm) | 44 | 6.18 | 3.88 | |

| 1) Treatment group | 20 | 6.55 | 4.47 | 0.962 |

| 2) Control group | 24 | 5.88 | 3.38 | |

| Asymmetry index (%) | 44 | 14.28 | 10.59 | |

| 1) Treatment group | 20 | 15.90 | 12.10 | 0.487 |

| 2) Control group | 24 | 12.93 | 9.19 | |

| Occlusion time (in seconds) | 44 | 0.256 | 0.135 | |

| 1) Treatment group | 20 | 0.281 | 0.161 | 0.430 |

| 2) Control group | 24 | 0.236 | 0.107 |

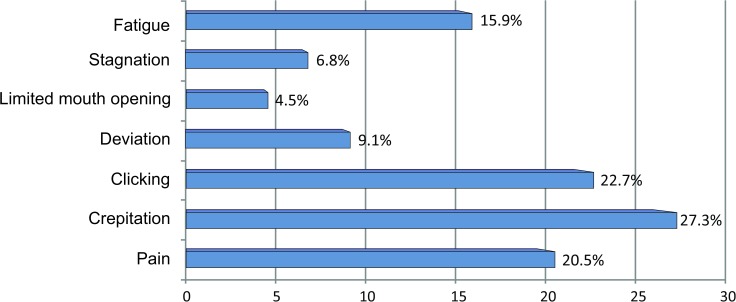

With reference to patients’ complaints and clinical symptoms, patients in the study group had from one to four complaints, 2.35 ± 0.33 complaints on average. (e.g., Fig. 1). When patients’ complaints and clinical symptoms were compared, the right TMJ was dominant (e.g., Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Complaints and clinical symptoms in the group of TMD patients

Fig. 2.

Distribution of TMD complaints and symptoms between left and right sides

To evaluate the relationship between occlusal parameters and patients’ complaints, the values of these parameters were compared between patients who were grouped by the presence and absence of complaints (Table 2). Statistically reliable differences of the centre of the occlusal force and the asymmetry index were obtained in the groups of patients who suffered from pain and those who did not feel it (p < 0.05). No other significant differences of occlusal parameters were detected in the groups with present and absent complaints (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of complaints from patients with TMDs and digital occlusion data

| Complaints | Number of patients | Occlusal parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre of occlusive force (mm) | Asymmetry index (%) | Occlusion time (s) | ||

| Pain: | ||||

| 1) Present | 9 | 8.56 ± 1.00* | 21.89 ± 3.24* | 0.304 ± 0.463 |

| 2) Absent | 35 | 5.57 ± 0.66 | 12.32 ± 1.69 | 0.244 ± 0.224 |

| Crepitation: | ||||

| 1) Present | 12 | 6.83 ± 1.47 | 15.37 ± 4.35 | 0.264 ± 0.383 |

| 2) Absent | 32 | 5.94 ± 0.60 | 13.87 ± 1.53 | 0.253 ± 0.243 |

| Clicking: | ||||

| 1) Present | 10 | 4.60 ± 0.82 | 10.55 ± 2.50 | 0.296 ± 0.038 |

| 2) Absent | 34 | 6.65 ± 0.70 | 15.38 ± 1.91 | 0.245 ± 0.024 |

| Deviation: | ||||

| 1) Present | 4 | 5.00 ± 1.92 | 11.30 ± 4.29 | 0.308 ± 0.137 |

| 2) Absent | 40 | 6.30 ± 0.62 | 14.58 ± 1.71 | 0.251 ± 0.186 |

| Limited mouth opening: | ||||

| 1) Present | 2 | 7.00 ± 4.00 | 27.10 ± 14.00 | 0.164 ± 0.045 |

| 2) Absent | 42 | 6.14 ± 0.60 | 13.67 ± 1.54 | 0.261 ± 0.021 |

| Stagnation: | ||||

| 1) Present | 3 | 4.00 ± 2.00 | 14.40 ± 9.90 | 0.246 ± 0.094 |

| 2) Absent | 41 | 6.34 ± 0.61 | 14.27 ± 1.61 | 0.257 ± 0.021 |

| Fatigue: | ||||

| 1) Present | 7 | 6.57 ± 1.33 | 18.07 ± 4.36 | 0.252 ± 0.052 |

| 2) Absent | 37 | 6.11 ± 0.66 | 13.56 ± 1.71 | 0.257 ± 0.022 |

* – statistically reliable differences (p < 0.05).

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curves were used to evaluate the diagnostic quality of occlusal parameters: the centre of the occlusion force and the asymmetry index. Patients with the centre of occlusion force distanced at least 7.5 mm complained of pain considerably more frequently than those with the centre of the occlusion force distanced less than 7.5 mm: 46.2% and 9.7%, respectively (p < 0.05). The probability of pain for these patients increased by 8.0 times (95%, confidence interval (CI): 1.59–40.20). Patients with the asymmetry index of and above 14% also complained of pain significantly more frequently than patients with the asymmetry index below 14%: 44.4% and 3.8%, respectively (p < 0.05). The probability of pain for these patients increased by 20.0 times (95%, confidence interval (CI): 2.21–181.30).

Based on the relation of occlusal parameters with pain and considering other parameters, a model of logistic regression was developed, which included the following characteristics: age, sex, centre of the occlusal force, and the asymmetry index. The analysis showed that there was no significant relation between patients’ pain condition and their age and gender. When the influence of other parameters was disregarded, the relation between the centre of the occlusal force and pain was stronger: when the distance was at least 7.5 mm, the probability of pain increased by 10.18 times (95%, CI: 1.304–79.382). The relation between pain and the asymmetry index was slightly weaker: when the index was at least 14%, the probability of pain increased by 19.02 times (95%, CI: 1.698–212.942).

DISCUSSION

The values of occlusal parameters – the centre of the occlusal force, the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force, and occlusion time – in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders were higher than in healthy subjects but the differences were not statistically significant. The impact and role of occlusion in the aetiology of TMDs has remained debatable. Therefore, the aim of this study was to employ a digital analysis to investigate the relation between static occlusal parameters and clinical symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorders.

Our study considered occlusion time and showed that the differences between healthy patients and those suffering from TMDs were not statistically significant. But the average values of occlusion time were different: it was 0.045 s longer compared to the control group. Results of this study are similar to the results of studies carried out by Baldini, Nota and Cozza in Italy in 2014: occlusion time longer by 0.18 s was recorded among treatment groups but the average of patients with TMDs was 0.64 ± 0.21, whereas the results were statistically significant. The differences between the study methods and a larger size of the sample could have influenced higher average values but it can still be noted that a longer occlusion time was recorded in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. This conclusion also applies to the results of the study by Wang and Yin (2012): the reported average value of occlusion time was 1.36 ± 0.03 s longer than in the control group, whereas the average in patients with TMDs was as high as 2.05 ± 0.06 s (16). We may assume that this difference was determined by patients suffering from severe forms of TMDs (6).

The distance of the centre of the occlusal force informs us about the occlusal balance but its extent may also be influenced by the function of masticatory muscles (16). The average value of the centre of the occlusal force recorded in this study was 6.55 ± 0.99 mm in the treatment group and 5.88 ± 0.69 mm in the control group; the differences were not statistically significant. In the study by Wang and Yin (2012), the average of patients with TMDs (4.39 ± 0.15 mm) was also higher than that of healthy subjects, but the differences were statistically significant (16). Drawing on the previous studies, it may be noted that patients with TMDs have a more extensive centre of occlusive force than those who have no complaints of TMDs; thus, occlusal imbalance is observed. But this difference was not statistically significant in our research.

The difference of the occlusal force between the right and the left sides is expressed as the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the study sample, but the average value of this parameter in the treatment group was higher than in the control group. The results in the study by Wang and Yin (2012) were similar: the average of the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force was 16.66 ± 0.47 (16). Thus, occlusal forces between both sides of the mandible are distributed unevenly in patients with TMDs, which results in the activity of masticatory muscles on one or two sides and may determine disorders in the temporomandibular joint.

The calculation of these dynamic parameters of occlusion did not show a statistically significant difference in the groups of the study sample, even though the average values were different. We may assume that the reasons for this were a small size of the sample, the variety of patients’ complaints and clinical symptoms, and the degree of severity of the disorders.

One of the objectives of our study was to evaluate the relationship between dynamic parameters of digital occlusion analysis and patients’ complaints and clinical symptoms. The results imply that irreversible dislocation of the articular disk is less prevalent than reversible, as the symptom of clicking was recorded in 22.7% of the patients. It may also be noted that pain in the temporomandibular joint coincides with functional imbalance of stomatognathic system, changes in the movements of the lower mandible, and emerging muscular hypoactivity; therefore, the force of chewing and pressure decreases (30). Subsequently, occlusal forces distribute unevenly on both dental arches during occlusion and an imbalance between distributions of forces on one side of the mandible with respect to the other side emerges. The study by overseas authors on the relationship between TMDs and occlusion (4, 6, 16) has not considered patients’ complaints. Studies of this kind have not been found.

To summarize the results of this study, we may conclude that the changes of occlusal parameters in the centric occlusion are characteristic of the patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. Still, not only occlusal and articulatory surfaces play an important role in the human articulatory system, but also masticatory muscles that regulate the movements of the lower mandible and determine the position of mandibular condyle in the articulatory structures during exercise and at rest. Thus occlusion remains only one of the predisposing factors in the aetiology of TMDs. The findings of this study need to be confirmed in additional studies on bigger samples and our study could be the pilot study for the approbation of the use this method.

CONCLUSIONS

There exists a relation between complaints of patients with TMD and static occlusion parameters. A statistically significant relationship between the distance of the centre of the occlusal force, the asymmetry index of maximum occlusal force, and patients’ pain in the area of temporomandibular joint was observed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Violeta Šimatonienė, a lecturer at the Department of Mathematics and Biophysics, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Agnė Dzingutė, Gaivilė Pileičikienė, Aušra Baltrušaitytė, Gediminas Skirbutis

References

- Carlsson GE. Critical review of some dogmas in prosthodontics. J Prosthodont Res. 2009; 53: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther F. TMD and occlusion part II. Damned if we don’t? Functional occlusal problems: TMD epidemiology in a wider context. Br Dent J. 2007; 202: 38–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-F Jung-Chih L Yang Hui-Wen Lee Yu-Hsien Yu Chuan-Hang. . Clinical effectiveness of laser acupuncture in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorder. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014; 113: 535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralur SB. Digital evaluation of functional occlusion parameters and their association with temporomandibular disorders. JJ Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7(7): 1772–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane TV, Kenealy P, Kingdon HA, Mohlin BO, Pilley JR, Richmond S, et al. Twenty-year cohort study of health gain from orthodontic treatment: Temporomandibular disorders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135(135): 692.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini A, Nota A, Cozza P. The association between occlusion time and temporomandibular disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2015; 25: 151–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullinger AG, Seligman DA, Gornbein JA. A multiple regression analysis of risk and relative odds of temporomandibular disorders as a function of common occlusal features. J Dent Res. 1993; 72: 968–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BH. Temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surgery, Oral medicine, Oral pathology 1999; 88(88): 379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegužytė A, Bernotas J. Smilkininio apatinio žandikaulio sąnario disfunkcijos etiologinių veiksnių ir prevencijos kriterijų apžvalga [Temporomandibular joint dysfunction etiology and prevention criteria review]. Stominfo. 2011; 6: 17–20. Lithuanian. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Opstelten D, Samman N, Tideman H. Experimentally induced unilateral tooth loss: expression of type II collagen in temporomandibular joint cartilage. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61: 1054–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Qiu-Fei X, Kai L, Light AR, Kai-Yuan F. Experimental occlusal interference induces longterm masticatory muscle hyperalgesia in rats. Pain. 2009; 144: 287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar KI, Srivastava A. A health technology assessment report on the utility of digital occlusal analyzer system T-Scan® in temporomandibular disorders. DENT 655–Health Technology Assessment 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gedrimas V, Burneckis E, Kubilius R, Grabliauskienė Ž, Pacauskienė I, Šidlauskas A. et al. , Dantų anatomija. Sąkandis [Dental anatomy. Occlusion]. Kaunas: KMU leidykla; 2010. Lithuanian. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos J Blackman RB Nelson SJ. Vectorial analysis of the static equilibrium of forces generated in the mandible in centric occlusion, group–function, and balanced occlusion relationships. J Prosthet Dent. 1991; 65: 557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Peter E. Function occlusion: from TMJ to smile design. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Yin X. Occlusal risk factors associated with temporomandibular disorders in young adults with normal occlusions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2012; 114: 419–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos B, Godt A, Schille C, Goz G. Precision of an instrumentation-based method of analyzing occlusion and its resulting distribution of forces in the dental arch. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie. 2010; 71: 403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstein RB, Radke J. Masseter and temporalis excursive hyperactivity decreased by measured anterior guidance development. Cranio. 2012; 30: 243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierpinska T, Kuc J, Golebiewska M. Assessment of masticatory muscle activity and occlusion time in patients with advanced tooth wear. Arch Oral Biol. 2015; 60: 1346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saracoglu A, Ozpinar B. In vivo and in vitro evaluation of occlusal indicator sensitivity. J Prosthet Dent. 2002; 88(88): 522–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patyk A, Lotzmann U, Scherer C, Kobes LW. Comparative analytic occlusal study of clinical use of T-scan systems. ZWR 1989; 98: 752–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throckmorton GS, Rasmussen J, Caloss R. Calibration of T–Scan sensors for recording bite forces in denture patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2009; 36(36): 636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester SE, Presswood RG, Toy AC. Pain MT. Occlusal measurement method can affect SEMG activity during occlusion. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2011; 38(38): 655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroni CR, Oliveira AS, Guaratini MI. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in university students. J Oral Rehabil. 2003; 30: 283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations if the international RDC/TMD consortium network and orofacial pain special interest group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014; 28: 6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Blanco C Penas FC Llave-Rincon AI Zarco-Moreno P Rio Peter Svensso FG. Characteristics of referred muscle pain to the head from active trigger points in women with myofascial temporomandibular pain and fibromyalgia syndrome. J Headache Pain. 2012; 13: 625–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetto MO Hotta TH Andrade Pizzo RC. . Measurements of jaw movements and TMJ pain intensity in patients treated with GaAlAs laser. Braz Dent J. 2010; 21(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HN, Kim KA, Koh KJ. Relationship between pain and effusion on magnetic resonance imaging in temporomandibular disorder patients. Imaging Sci Dent. 2014; 44(44): 293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshvad A, Winstanley RB. Comparison of the replicability of routinely used centric relation registration techniques. J Prosthodont. 2003; 12(12): 90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansdottir R, Bakke M. Joint tenderness, jaw opening, chewing velocity, and bite force in patients with temporomandibular joint pain and matches control subjects. J Orofac Pain. 2004; 18(18): 108–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]