Abstract

Accumulating evidence implicates innate immune activation in the pathobiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. A key myeloid-related inflammatory protein, S100A9, serves as a Toll-like receptor ligand regulating tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β production. The role of myelodysplastic syndrome-related inflammatory proteins in endogenous erythropoietin regulation and response to erythroid-stimulating agents or lenalidomide has not been investigated. The HepG2 hepatoma cell line was used to investigate in vitro erythropoietin elaboration. Serum samples collected from 311 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome were investigated (125 prior to treatment with erythroid-stimulating agents and 186 prior to lenalidomide therapy). Serum concentrations of S100A9, S100A8, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and erythropoietin were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Using erythropoietin-producing HepG2 cells, we show that S100A9, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β suppress transcription and cellular elaboration of erythropoietin. Pre-incubation with lenalidomide significantly diminished suppression of erythropoietin production by S100A9 or tumor necrosis factor-α. Moreover, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, lenalidomide significantly reduced steady-state S100A9 generation (P=0.01) and lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-α elaboration (P=0.002). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays of serum from 316 patients with non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes demonstrated a significant inverse correlation between tumor necrosis factor-α and erythropoietin concentrations (P=0.006), and between S100A9 and erythropoietin (P=0.01). Moreover, baseline serum tumor necrosis factor-α concentration was significantly higher in responders to erythroid-stimulating agents (P=0.03), whereas lenalidomide responders had significantly lower tumor necrosis factor-α and higher S100A9 serum concentrations (P=0.03). These findings suggest that S100A9 and its nuclear factor-κB transcriptional target, tumor necrosis factor-α, directly suppress erythropoietin elaboration in myelodysplastic syndromes. These cytokines may serve as rational biomarkers of response to lenalidomide and erythroid-stimulating agent treatments. Therapeutic strategies that either neutralize or suppress S100A9 may improve erythropoiesis in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes.

Introduction

Ineffective erythropoiesis in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) derives from both intrinsic abnormalities affecting the response to erythropoietin and extrinsic pressures on the inflammatory bone marrow microenvironment.1 A number of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and others, are generated in excess in MDS and adversely influence hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell survival.2 Moreover, in a subset of MDS patients, endogenous erythropoietin production is deficient, further compromising erythropoietic potential.3 Accumulating evidence implicates innate immune activation in the physiopathology of MDS and the accompanying inflammatory microenvironment.1,2,4,5 Bone marrow plasma concentrations of the pro-inflammatory, danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein, S100A9, are profoundly increased in lower-risk MDS, which serves as a catalyst directing myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion.6 S100A9 is a ligand for CD33 and the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 which, through nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation, regulates the transcription and cellular elaboration of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β.7 The latter cytokines have been shown to suppress erythropoietin elaboration and have been implicated in the suppression of endogenous erythropoietin production8 in patients with anemia of chronic inflammation.9 The involvement of 100A8/S100A9 in del(5q) MDS has already been described.10 Erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESA) and lenalidomide are efficient treatments used in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes.11–13 To date, the role of inflammatory parameters in the regulation of endogenous erythropoietin production and response to erythropoietic treatments in MDS has not been investigated. Here we show the importance of these inflammatory cytokines as key biological determinants of endogenous erythropoietin production and response to ESA and lenalidomide treatments in patients with non-del (5q) MDS.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant S100A9 was generated as previously described.6 TNFα, IL-1β and lipopolysaccharide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Lenalidomide was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). A CD33 chimera was constructed as described elsewhere.6,14 NF-κB and Rho GDI antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Lamin A/C was purchased from Cell signaling (Saint Quentin, France). BMS344541 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

Cell culture

HepG2 cells, acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), were grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution. Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Human S100A9/MRP14 in patients’ serum and supernatants of the HepG2 cell line was quantified using a CircuLex S100A9/MRP14 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit (MBL, Nagano, Japan). Quantitative measurements of human TNFα and IL-1β were made using the Human TNFα ELISA Kit and Human IL-1β ELISA Kit, respectively (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Human erythropoietin in patients’ serum and HepG2 cell line supernatants was quantified using a Human Erythropoietin ELISA Kit (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). All measurements were performed in duplicate.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated using the RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) followed by iScript cDNA synthesis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and amplification using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Herculed, CA, USA). The relative level of gene expression for each experimental sample was calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Untreated cells were the experimental control and the housekeeping gene GAPDH was the endogenous control.

Western blot analysis

After treatment for 24 h, cells were harvested and lysed in 1X RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors for classical western blotting. For the nuclear extraction, cells were lysed in ice with buffer A, then pelleted. After removal of supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction), pellets were lysed in ice with buffer B and pelleted (nuclear fraction) (Nuclear Extraction Kit, Abcam, Cambridge, USA). Lysates were pelleted and 50 μg of protein were resolved by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked for 30 min in 5% nonfat dry milk solution in PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with the indicated antibodies. Membranes were developed using ECL according to the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Densitometry analysis was performed using Image J Software.

Patients and serum samples

Serum samples for ELISA analysis were collected from four centers (Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland, USA AOU Careggi, University of Florence, Italy; Saint Louis Hospital, Paris, France; H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected from patients at Moffitt Cancer Center. All patients had provided consent to Institutional Review Board, or equivalent, approved protocols in hematology clinics at each center, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) E2905 trial (www.clinicaltrial.gov NCT00843882). All routine clinical and biological data were available.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error for continuous variables, or percentage of total for non-continuous variables. Spearman correlation, Mann-Whitney and Jonckheere-Terpstra tests were used for analysis of continuous variables. The chi-square test was used for analysis of non-continuous variables. Differences between the results of comparative tests were considered statistically significant if the two-sided P-value was less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.22 software (IBM SPSS Statistics).

Results

Inflammatory proteins suppress erythropoietin production by HepG2 cells

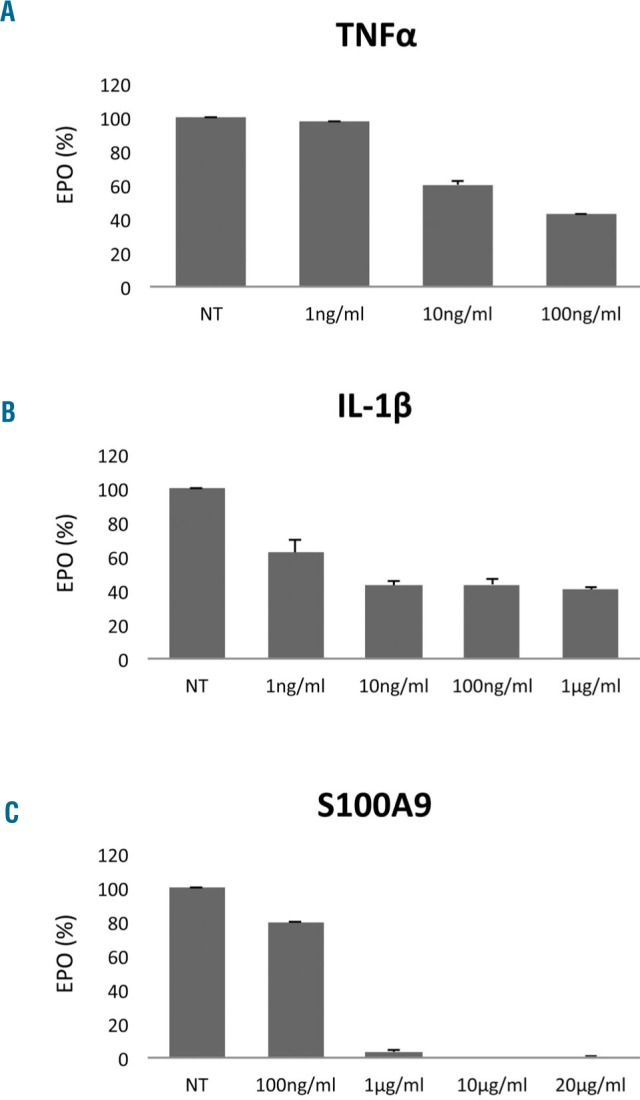

Hepatoma HepG2 cells, which produce erythropoietin under basal conditions,15 were treated with varied concentrations of each of the inflammatory proteins, TNFα, IL-1β or S100A9. After 24 h exposure, we observed a concentration-dependent reduction in erythropoietin elaboration (Figure 1). At a concentration of 10 ng/mL, TNFα yielded a 40% reduction in erythropoietin elaboration (Figure 1A), compared to a 60% reduction following incubation with IL-1β (Figure 1B). Concentrations of 10 to 20 μg/mL of S100A9 completely suppressed erythropoietin elaboration, while 1 μg/mL yielded a 95% reduction (Figure 1C). For subsequent experiments, concentrations of 10 ng/mL of TNFα, 10 ng/mL of IL-1β and 1 μg/mL of S100A9 were employed.

Figure 1.

Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and S100A9 on erythropoietin elaboration in the HepG2 cell line. HepG2 cells were stimulated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of (A) TNFα, (B) IL-1β and (C) S100A9 and erythropoietin (EPO) elaboration was determined by ELISA.

Lenalidomide mitigates suppression of erythropoietin production by S100A9 and tumor necrosis factor-α

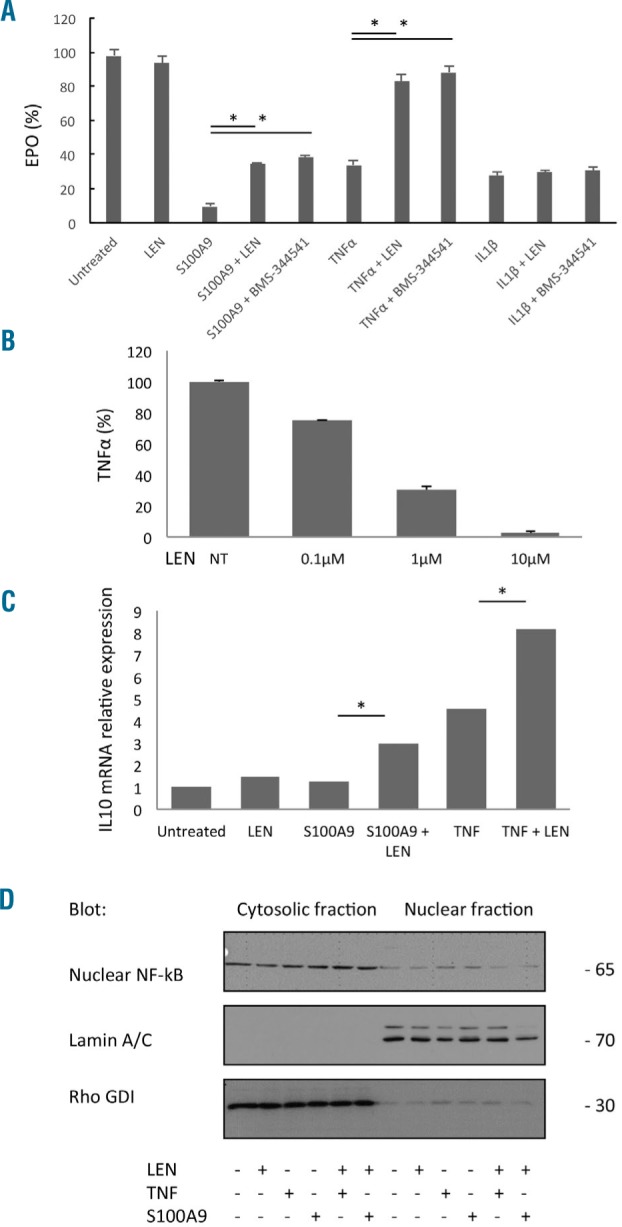

The transcription factor NF-κB is activated by TLR ligands and inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα which, like GATA2, is implicated in transcriptional suppression of the erythropoietin transcript.16 HepG2 cells are known to express the S100A9 receptor, TLR4, on the plasma membrane.17 Lenalidomide has been reported to suppress NF-κB activation in response to inflammatory cytokine stimulation in lymphocytes and other cell lineages.18,19 To determine whether lenalidomide can modulate suppression of erythropoietin production by inflammatory proteins, we treated HepG2 cells with 1 μM lenalidomide or vehicle control for 30 min prior to exposure to TNFα, IL-1β or S100A9. Lenalidomide significantly, but incompletely, reversed suppression of erythropoietin production by S100A9 (91% suppression by S100A9 versus 65% after lenalidomide pre-incubation, P=0.04). Following treatment with TNFα, lenalidomide pre-treatment abrogated cytokine suppression of erythropoietin elaboration (TNFα, 67% suppression versus lenalidomide pre-incubation, 18% P=0.05). Lenalidomide had no effect on IL-1β-directed suppression of erythropoietin elaboration (Figure 2A). We also found that BMS-344541, a specific inhibitor of NF-κB, abrogated cytokine suppression of erythropoietin elaboration with the same conditions (Figure 2A). Moreover, lenalidomide decreased basal TNFα release after lenalidomide stimulation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of lenalidomide on erythropoietin elaboration in the HepG2 cell line. (A) HepG2 cells were treated with 1 μM lenalidomide for 30 min prior to addition of S100A9 (1 μg/mL), TNFα (10 ng/mL) or IL-1β (10 ng/mL). Supernatant erythropoietin (EPO) concentration was determined by ELISA (B) HepG2 cells were treated with 0.1, 1 or 10 μM lenalidomide. Supernatant TNFα concentration was determined by ELISA (C) HepG2 cells were treated with 1 μM lenalidomide 30 min prior to addition of S100A9 (1 μg/mL) or TNFα (10 ng/mL). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for IL10 mRNA expression was performed 24 h after treatment. GAPDH was used as an endogenous control and results are expressed as IL10 mRNA relative expression. (D) HepG2 cells were treated with 1 μM lenalidomide 30 min before addition of S100A9 (1 μg/mL) or TNFα (10 ng/mL). NF-κB protein was visualized by western blot 24 h after treatment. Rho GDI and lamin A/C were used as the loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. *mean P≤0.05.

IL-10 is known to be an anti-inflammatory cytokine secreted by immune cells.20 We performed quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis to determine the effects of the inflammatory proteins and lenalidomide on IL10 gene transcription. Pre-incubation of each inflammatory cytokine with lenalidomide significantly increased IL10 mRNA expression compared to S100A9 or TNFα treatment alone (Figure 2C). Lenalidomide had no modulatory effect on IL10 following IL-1β treatment (data not shown).

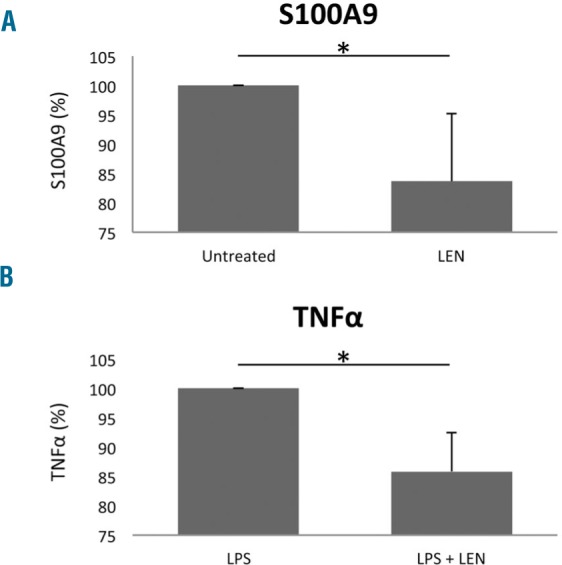

Finally, NF-κB is a key transcription factor involved in S100A9 and TNFα receptor signaling and the transcriptional suppression of erythropoietin mRNA in erythropoietin-producing cells which is modulated by lenalidomide.21–23 We showed that NF-κB targets, including TNFα and IL-10, were regulated by lenalidomide. We therefore performed cytoplasmic and nuclear NF-κB western blotting in HepG2 cells to discern the effect of lenalidomide on inflammatory protein signaling. As demonstrated by nuclear localization after lenalidomide pre-incubation, active NF-κB was significantly reduced following treatment with S100A9 or TNFα, indicating that lenalidomide suppressed NF-κB activation (Figure 2D). To confirm the results observed in HepG2 cells, we investigated the effects of lenalidomide on steady-state production of S100A9 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with non-del(5q) MDS (n=7). ELISA showed a significant reduction in S100A9 elaboration after 24 h exposure to lenalidomide (P=0.01) (Figure 3A). Similarly, pre-incubation of MDS peripheral blood mononuclear cells with lenalidomide significantly reduced TNFα production induced by lipopolysaccharide (P=0.002). These findings indicate that lenalidomide-modulated S100A9 and TNFα suppression of erythropoietin elaboration is NF-κB-dependent.

Figure 3.

Effect of lenalidomide on S100A9 and tumor necrosis factor-α production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndrome. (A) Frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from lower-risk MDS patients (n=7) were treated with 1 μM lenalidomide for 24 h, before analysis of supernatant S100A9 concentration by ELISA. Results are expressed relative to untreated cells. (B) PBMC from lower-risk MDS patients (n=7) were treated with 1 μM lenalidomide 30 min prior to addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 μg/mL): 24 h after stimulation, TNFα ELISA was performed on the supernatants. Results are expressed as a percentage relative to LPS treatment alone. *mean P≤0.05.

Relationship between inflammatory proteins and endogenous erythropoietin concentration in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes

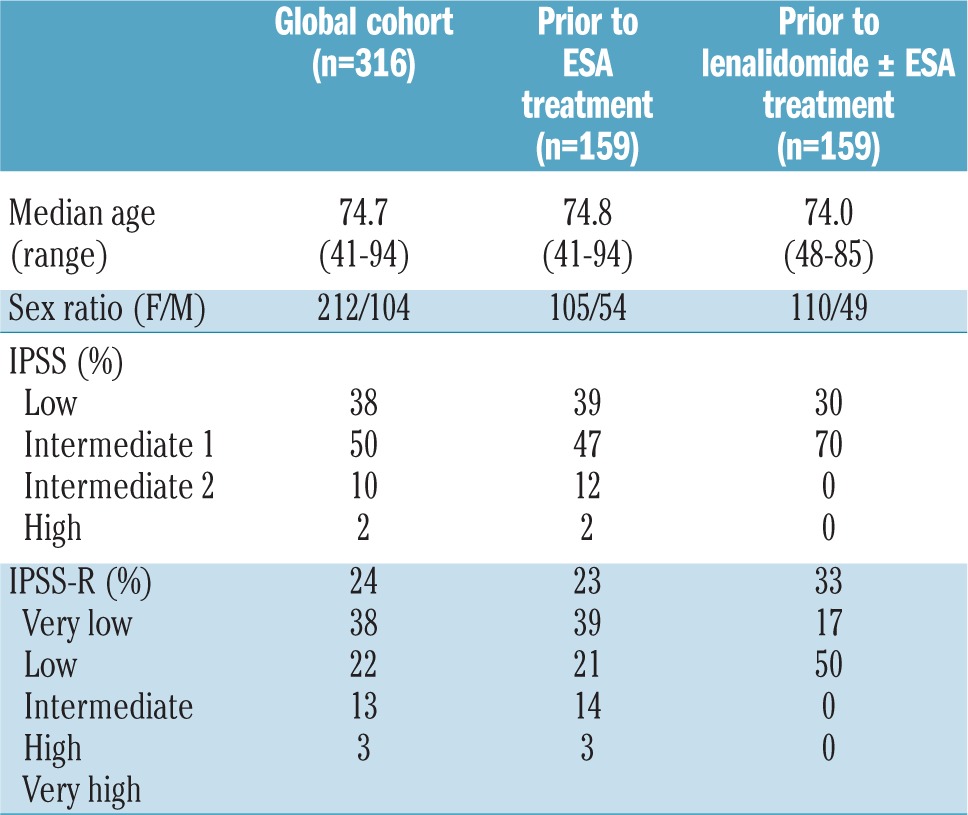

To validate the regulatory role of inflammatory proteins on erythropoietin elaboration in vivo, we assessed the relationships between serum concentrations of various inflammatory cytokines and erythropoietin in MDS patients with symptomatic anemia. Serum samples from 316 patients with non-del(5q) MDS were analyzed. The median age of the patients was 74.7 years (range, 41–94). Distribution of International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) categories was low, intermediate-1, intermediate-2 and high risk in 38%, 50%, 10% and 2% of patients, respectively whereas 24%, 38%, 22%, 13% and 3% of patients were very low, low, intermediate, high and very high risk according to the revised IPSS (IPSS-R) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics and disease characteristics.

Serum concentrations of erythropoietin, S100A9, S100A8, TNFα and IL-1β were assessed by ELISA. The serum S100A9 concentration was significantly higher in patients with lower-risk MDS than in those with higher-risk MDS [12,226 pg/mL (range, 0–228,880) versus 240 pg/mL (range, 0–43,858), respectively P=0.001). No significant differences were observed in TNFα and IL-1β concentrations according to IPSS or IPSS-R category (data not shown).

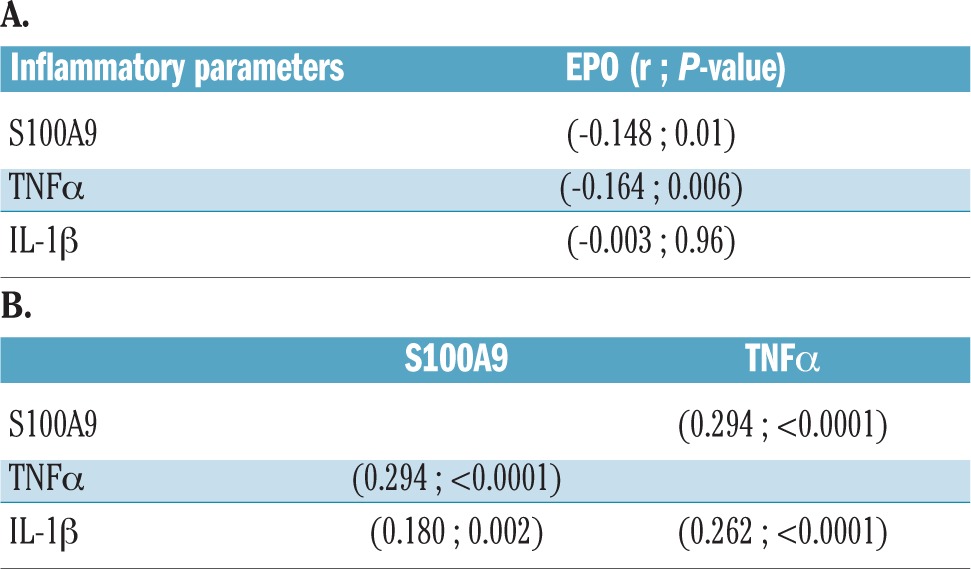

There was a statistically significant negative correlation between TNFα and erythropoietin concentrations (r= − 0.164, P=0.006), and between S100A9 and erythropoietin concentrations (r= −0.148, P=0.01), whereas there was no discernible relationship between IL-1β and erythropoietin concentrations (Table 2A and Online Supplementary Figure S1). As expected, we also found significant positive correlations between the concentrations of the inflammatory protein S100A9 and TNFα (r=0.294, P<0001), S100A9 and IL-1β (r=0.180, P=0.002), as well as IL-1β and TNFα (r=0.262, P<0.001) (Table 2B). These findings support the notion that S100A9 and TNFα suppress renal erythropoietin elaboration and the endocrine response to anemia in non-del(5q) MDS.

Table 2.

(A) Correlations between concentrations of inflammatory proteins and erythropoietin (EPO) in patients’ serum. (B) Relationships between inflammatory proteins.

Relationships between inflammatory protein concentrations and response to treatment with erythropoietic agents

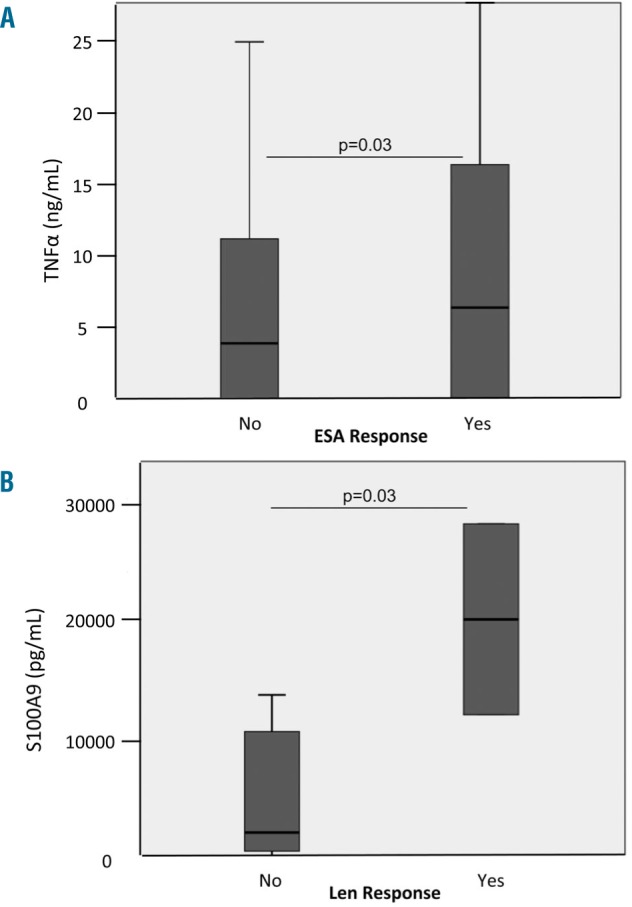

Within the cohort of patients with non-del(5q) MDS, 159 were studied prior to ESA treatment and 159 prior to lenalidomide ± erythropoietin treatment (Table 1). ESA responders had significantly higher serum TNFα concentrations than non-responders (8.37 pg/mL versus 3.79 pg/mL, respectively P=0.03) with a corresponding significantly lower erythropoietin concentration in ESA responders (36 mU/mL versus 113 mU/mL, respectively P<0.0001). Erythroid response rate was 43% versus 55% in patients with low versus high TNFα concentration, respectively (Figure 4A). There was no significant relationship between S100A9 serum concentration and erythropoietin response (data not shown). Nevertheless, erythropoietin concentration was a better biomarker of response to ESA than was TNFα concentration even after adjustment for erythropoietin concentration. Finally, among patients treated with lenalidomide or lenalidomide ± erythropoietin, responding patients had significantly lower serum TNFα concentrations (P=0.02) while there was no relationship with S100A9 concentration (P=0.21). Considering responses to lenalidomide, we observed a significant difference in erythroid response rate (62% versus 12% for patients with low versus high S100A9 serum concentration, respectively P=0.03) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Relationship between serum concentrations of inflammatory proteins and response to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or lenalidomide treatment. (A) Correlation between serum concentrations of inflammatory proteins and response to ESA or (B) lenalidomide treatment.

Discussion

Pro-inflammatory cytokines have long been implicated as key effectors of anemia in disorders of chronic inflammation and malignancy.24 Indeed, TNFα antagonists have been shown to improve anemia in several inflammatory disorders.25 The pathogenesis of ineffective erythropoiesis in MDS, in particular, is multifactorial, including abnormalities inherent to the neoplastic clone as well as the inflammatory bone marrow microenvironment.26 Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, interferon-γ, transforming growth factor-β and TNFα directly inhibit erythroid progenitor colony-forming capacity in vitro and impair iron turnover.27–29 Moreover, both IL-1β and TNFα suppress erythropoietin gene expression and protein secretion in a NF-κB-dependent fashion,30 factors which have been implicated in the disproportionately low endogenous erythropoietin production in response to the anemia of inflammation. In a subset of lower-risk MDS patients who are responsive to treatment with recombinant erythropoietin, renal erythropoietin production is suppressed with a corresponding reduction in serum erythropoietin concentration. The precise physiological events that impair erythropoietin production in lower-risk MDS do, however, remain unexplored. Our investigations show that S100A9, a myeloid-derived inflammatory protein produced in excess in MDS, directly suppresses erythropoietin transcription and elaboration in HepG2 hepatoma cells, analogous to the actions of TNFα.6 Moreover, S100A9 serves as a key coordinator of the inflammatory response by inducing the secretion of TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β via TLR4-dependent activation of NF-κB.30,31 Our findings support the notion that these inflammatory cytokines similarly suppress erythropoietin production in vivo in lower-risk MDS patients. Serum erythropoietin concentration was inversely related to S100A9 and TNFα concentrations. Furthermore, serum TNFα concentration was significantly higher in patients responding to treatment with recombinant erythropoietin than in non-responders (P=0.03). Previous investigations showed that higher serum TNFα concentration predicted resistance to ESA: our data do, therefore, need to be confirmed in a larger study.32,33 Of particular interest, lenalidomide suppressed nuclear translocation of NF-κB to mitigate the suppression of erythropoietin production in HepG2 cells by both S100A9 and TNFα. The ability of lenalidomide to modulate cytokine activation may not only reduce progenitor cell injury, but may also relieve repression of renal erythropoietin elaboration and, therefore, the endocrine response to anemia in MDS. We found that the serum concentration of TNFα was significantly lower and serum concentration of S100A9 was higher in lenalidomide-responsive patients (P=0.03). Together, these findings indicate that S100A9 and its transcriptional target, TNFα, directly suppress erythropoietin elaboration and endocrine response to anemia in MDS and may be useful biomarkers of response to treatment with lenalidomide or recombinant erythropoietin, meriting further investigation. More importantly, our findings suggest that therapeutic strategies that either neutralize or suppress S100A9 may improve erythropoiesis in lower-risk MDS by suppressing inflammatory cytokine generation and restoring endocrine erythropoietin response to anemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Foundation Nuovo Soldati, Phillippe Foundation and “Les amis de la faculte de medecine de Nice” (to TC).

Footnotes

Check the online version for the most updated information on this article, online supplements, and information on authorship & disclosures: www.haematologica.org/content/102/12/2015

References

- 1.Ganan-Gomez I, Wei Y, Starczynowski DT, et al. Deregulation of innate immune and inflammatory signaling in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2015;29(7): 1458–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Qian Y, Eksioglu E, Epling-Burnette PK, Wei S. The inflammatory microenvironment in MDS. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(10):1959–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valent P. Low erythropoietin production as non-oncogenic co-factor contributing to disease-manifestation in low-risk MDS: a hypothesis supported by unique case reports. Leuk Res. 2008;32(9):1333–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varney ME, Melgar K, Niederkorn M, Smith MA, Barreyro L, Starczynowski DT. Deconstructing innate immune signaling in myelodysplastic syndromes. Exp Hematol. 2015;43(8):587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boiko JR, Borghesi L. Hematopoiesis sculpted by pathogens: Toll-like receptors and inflammatory mediators directly activate stem cells. Cytokine. 2012;57(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Eksioglu EA, Zhou J, et al. Induction of myelodysplasia by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4595–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riva M, Kallberg E, Bjork P, et al. Induction of nuclear factor-kappaB responses by the S100A9 protein is Toll-like receptor-4-dependent. Immunology. 2012;137(2):172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faquin WC, Schneider TJ, Goldberg MA. Effect of inflammatory cytokines on hypoxia-induced erythropoietin production. Blood. 1992;79(8):1987–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertero MT, Caligaris-Cappio F. Anemia of chronic disorders in systemic autoimmune diseases. Haematologica. 1997;82(3):375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider RK, Schenone M, Ferreira MV, et al. Rps14 haploinsufficiency causes a block in erythroid differentiation mediated by S100A8 and S100A9. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toma A, Kosmider O, Chevret S, et al. Lenalidomide with or without erythropoietin in transfusion-dependent erythropoiesis-stimulating agent-refractory lower-risk MDS without 5q deletion. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S, Fenaux P, Greenberg P, et al. Efficacy and safety of darbepoetin alpha in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(5):730–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santini V, Almeida A, Giagounidis A, et al. Randomized phase III Study of lenalidomide versus placebo in RBC transfusion-dependent patients with lower-risk non-del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes and ineligible for or refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(25):2988–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon JP, O’Driscoll M, Litman GW. Construction, expression, and purification of chimeric protein reagents based on immunoglobulin Fc regions. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;748:51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porwol T, Ehleben W, Zierold K, Fandrey J, Acker H. The influence of nickel and cobalt on putative members of the oxygen-sensing pathway of erythropoietin-producing HepG2 cells. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256(1): 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Ferla K, Reimann C, Jelkmann W, Hellwig-Burgel T. Inhibition of erythropoietin gene expression signaling involves the transcription factors GATA-2 and NF-kappaB. FASEB J. 2002;16(13):1811–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao CC, Chen PH, Cheng CI, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 is a target for suppression of proliferation and chemoresistance in HepG2 hepatoblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;368(1):144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crane E, List A. Immunomodulatory drugs. Cancer Invest. 2005;23(7):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galili N, Raza A. Immunomodulatory drugs in myelodysplastic syndromes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15(7):805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299(5609):1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuckerman SH, Evans GF, Guthrie L. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms involved in the differential expression of LPS-induced IL-1 and TNF mRNA. Immunology. 1991;73(4):460–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szenajch J, Wcislo G, Jeong JY, Szczylik C, Feldman L. The role of erythropoietin and its receptor in growth, survival and therapeutic response of human tumor cells. From clinic to bench - a critical review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806(1):82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu K, Geczy CL. IFN-gamma and TNF regulate macrophage expression of the chemotactic S100 protein S100A8. J Immunol. 2000;164(9):4916–4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morceau F, Dicato M, Diederich M. Pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated anemia: regarding molecular mechanisms of erythropoiesis. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009: 405016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrado A, Di Bello V, d’Onofrio F, Maruotti N, Cantatore FP. Anti-TNF-alpha effects on anemia in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2017;30(3):302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calado RT. Immunologic aspects of hypoplastic myelodysplastic syndrome. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(5):667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang CQ, Udupa KB, Lipschitz DA. Interferon-gamma exerts its negative regulatory effect primarily on the earliest stages of murine erythroid progenitor cell development. J Cell Physiol. 1995;162(1):134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felli N, Pedini F, Zeuner A, et al. Multiple members of the TNF superfamily contribute to IFN-gamma-mediated inhibition of erythropoiesis. J Immunol. 2005;175(3): 1464–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taniguchi S, Dai CH, Price JO, Krantz SB. Interferon gamma downregulates stem cell factor and erythropoietin receptors but not insulin-like growth factor-I receptors in human erythroid colony-forming cells. Blood. 1997;90(6):2244–2252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simard JC, Cesaro A, Chapeton-Montes J, et al. S100A8 and S100A9 induce cytokine expression and regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome via ROS-dependent activation of NF-kappaB(1.). PLoS One. 2013;8(8): e72138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernov AV, Dolkas J, Hoang K, et al. The calcium-binding proteins S100A8 and S100A9 initiate the early inflammatory program in injured peripheral nerves. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(18):11771–11784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musto P, Matera R, Minervini MM, et al. Low serum levels of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 beta in myelodysplastic syndromes responsive to recombinant erythropoietin. Haematologica. 1994;79(3): 265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stasi R, Brunetti M, Bussa S, et al. Serum levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha predict response to recombinant human erythropoietin in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Lab Haematol. 1997;19(3):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.