Abstract

Retention indices for 124 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and 62 methyl-substituted (Me-) PAHs were determined using normal-phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) on a aminopropyl (NH2) stationary phase. PAH retention behavior on the NH2 phase is correlated to the total number of aromatic carbons in the PAH structure. Within an isomer group, non-planar isomers generally elute earlier than planar isomers. MePAHs generally elute slightly later but in the same region as the parent PAHs. Correlations between PAH retention behavior on the NH2 phase and PAH thickness (T) values were investigated to determine the influence of non-planarity for isomeric PAHs with four to seven aromatic rings. Correlation coefficients ranged from r = 0.19 (five-ring peri-condensed molecular mass (MM) 252 Da) to r = −0.99 (five-ring cata-condensed MM 278 Da). In the case of the smaller PAHs (MM ≤ 252 Da), most of the PAHs had a planar structure and provided a low correlation. In the case of larger PAHs (MM ≥ 278 Da), nonplanarity had a significant influence on the retention behavior and good correlation between retention and T was obtained for the MM 278 Da, MM 302 Da, MM 328 Da, and MM 378 Da isomer sets.

Keywords: normal-phase liquid chromatography, retention index, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, non-planarity

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a class of environmental pollutants that have been identified as potential carcinogens and studies have shown that exposure to PAHs can lead to an increased risk of cancer [1–3]. These compounds often exist in complex mixtures of condensed multi-ring benzenoid compounds that originate from natural and anthropogenic sources. Methods used to quantify PAHs in complex matrix samples typically employ a single chromatographic technique or a combination of techniques such as normal-phase liquid chromatography (NPLC), reversed-phase (RP)-LC, and/or gas chromatography (GC). RPLC separations on a polymeric octadecylsilane (C18) stationary phase [4] and GC [5] on a 50% phenyl methylpolysiloxane (MPS) phase or 50% liquid crystalline dimethylpolysiloxane stationary phase has been shown to provide excellent separations of isomeric PAHs. NPLC is often used as a low resolution fractionation technique to isolate PAHs for further characterization by RPLC and/or GC [6–19].

Silica and alumina were the classical adsorbents used for decades with nonpolar solvents in open column chromatography for the isolation of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons (including PAHs). However, because of high absorptivity and the influence of moisture content, the use of these adsorbents for routine NPLC fractionation of PAHs was unreliable. In the late 1970s with the emergence of chemically-bonded LC stationary phases, the use of polar functionalized stationary phases in a NP mode became a viable alternative. Wise et al. [10] introduced the use of an aminopropyl (NH2) stationary phase for the separation and isolation of PAHs from complex mixtures. Wise et al. [10] investigated the retention behavior of 42 alkyl-substituted benzenes and two-ring to five-ring PAHs on the NH2 phase and compared the retention characteristics with classical silica [20] and alumina [21] data from the literature. They concluded that with the NH2 phase…. “when a nonpolar mobile phase such as n-hexane is used, a hydrocarbon class separation similar to that obtained on silica and alumina is achieved, i.e., saturated hydrocarbons elute before olefinic and aromatic hydrocarbons, and the elution volumes for the aromatic hydrocarbons increase with the number of condensed rings.”. In contrast to classical adsorbents where the addition of alkyl groups to the aromatic ring generally increased retention, they observed that the presence of an alkyl group had only a slight effect on retention, thereby providing a more distinct class (aromatic ring) fractionation with more reproducible retention than silica or alumina [10]. Wise et al. [10] attributed the retention behavior on the NH2 phase primarily to “the interaction between the aromatic π electrons of the PAHs and the polar amino group of the stationary phase.”. Following this initial study, Wise et al. [22] published additional NPLC retention data, as retention indices, for 31 parent PAHs with two to six aromatic rings and 38 alkyl-substituted PAHs commenting that retention was “… based on the number of condensed aromatic rings and on some steric considerations.”. A later study focusing on six-ring PAHs of molecular mass (MM) 302 Da reported the retention indices for 19 of these six-ring isomers [6].

Since these initial studies reporting retention indices [10, 22], Wise and coworkers have used the NH2 stationary phase extensively for fractionation of complex PAH matrices [6–8, 11–14] without expanding the investigation of the retention behavior to a greater number of PAHs. The original studies [10, 14, 22] were incorrect in looking at the separation as based on increasing number of condensed aromatic rings. In subsequent studies [6–8, 11–13] using the NH2 phase for PAH fractionation, this concept changed to the retention being based on the number of aromatic carbons rather than aromatic rings. May and Wise [11] first stated that the retention of PAHs on the NH2 phase was based on number of aromatic carbons, and they reported retention indices for seven deuterated PAHs, which were used as internal standards in PAH fractions isolated on the NH2 phase. In those studies, however, there was no formal evaluation or discussion of the retention based on number of aromatic carbons. In the current study, we revisit the NPLC retention of PAHs on the NH2 phase for a significantly greater number (i.e., 186) of PAHs and alkyl-PAHs and investigate the relationship of retention and number of aromatic carbons and the influence of non-planarity on the retention behavior. A similar study of NPLC retention behavior for polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles (PASHs) and their alkylated derivatives is published elsewhere [23]. In a companion study [24] the NPLC retention behavior of PAHs and MePAHs reported here is used as the basis to develop a NPLC fractionation procedure combined with GC/MS for characterizing the complex mixture of PAHs in a coal tar sample.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chemicals

Reference standards were obtained from several commercial sources including Bureau of Community Reference (Brussels, Belgium), Chiron AS (Trondheim, Norway), W. Schmidt (Ahrensburg, Federal Republic of Germany), Pfaltz and Bauer, Inc. (Waterbury, CT), Fluka Chemie AG. (Buchs, Switzerland), and the National Cancer Institute of Chemical Carcinogen Repository (Bethesda, MD). Additional reference standards were obtained from J. Jacob and G. Grimmer (Biochemical Institute for Environmental Carcinogens, Ahrensburg, Federal Republic of Germany), J. Fetzer (Chevron Research Co., Richmond CA), and A. K. Sharma (Penn State University, College of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA). The names and abbreviations for these standards are listed in Tables 1 – 5. HPLC grade n-hexane, dichloromethane (DCM), and toluene were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Table 1.

NPLC retention indices for the two-ring and three-ring PAHs.

| PAHs | Abbreviations |

MM (Da) |

No. of Aromatic Carbon |

Thickness (Å) |

Log I NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | Naph | 128 | 10 | 3.88 | 2.00 |

| Acenaphthylene | Acey | 152 | 12 | 3.88 | 2.68 |

| Acenaphthene | Ace | 154 | 10 | 4.22 | 2.27 |

| Fluorene | Flu | 166 | 12 | 4.24 | 2.72 |

| 1-Methylfluorene | 1-MeFlu | 180 | 12 | 5.13 | 2.82 |

| 2-Methylfluorene | 2-MeFlu | 180 | 12 | 5.02 | 2.74 |

| Anthracene | Ant | 178 | 14 | 3.88 | 2.93 |

| 1-Methylanthracene | 1-MeAnt | 192 | 14 | 4.21 | 2.92 |

| 2-Methylanthracene | 2-MeAnt | 192 | 14 | 4.20 | 2.96 |

| 9-Methylanthracene | 9-MeAnt | 192 | 14 | 4.14 | 3.03 |

| Phenanthrene | Phe | 178 | 14 | 3.89 | 3.00 |

| 1-Methyphenanthrene | 1-MePhe | 192 | 14 | 4.22 | 3.05 |

| 2-Methyphenanthrene | 2-MePhe | 192 | 14 | 4.20 | 3.06 |

| 4-Methyphenanthrene | 4-MePhe | 192 | 14 | 4.69 | 3.02 |

| 9-Methyphenanthrene | 9-MePhe | 192 | 14 | 4.22 | 3.03 |

Table 5.

NPLC retention indices for the seven- and eight-ring PAHs.

| PAHs | Abbreviations |

MM (Da) |

No. of Aromatic Carbon |

Thickness (Å) |

Log I NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seven-Ring PAHs | |||||

| Coronene | Cor | 300 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.03 |

| Acenaphtho[1,2-j]fluoranthene | A12jF | 326 | 26 | 4.63 | 5.90 |

| Acenaphtho[1,2-k]fluoranthene | A12kF | 326 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.11 |

| Dibenzo[b,ghi]perylene | DBbghiPer | 326 | 26 | 3.90 | 5.68 |

| Dibenzo[e,ghi]perylene | DBeghiPer | 326 | 26 | 3.89 | 5.74 |

| Dibenzo[cd,lm]perylene | DBcdlmPer | 326 | 26 | 3.90 | 5.28 |

| Diindeno[1,2,3-de,1’,2’,3’-kl]anthracene | Rubicene | 326 | 26 | 3.89 | 5.82 |

| Naphtho[1,2,3,4-ghi]perylene | N1234ghiPer | 326 | 26 | 4.07 | 5.71 |

| Naphtho[8,1,2-bcd]perylene | N812bcdPer | 326 | 26 | 4.74 | 5.77 |

| Benzo[a]naphtho[8,1,2-cde]naphthacene | BaN812cdeNap | 352 | 28 | 4.37 | 6.50 |

| Benzo[vwx]hexaphene | BvwxHexa | 352 | 28 | 3.89 | 6.35 |

| Dibenzo[h,rst]pentaphene | DBhrstPenta | 352 | 28 | 4.31 | 6.57 |

| Benzo[a]naphtho[1,2-j]naphthacene | BaN12jNap | 378 | 30 | 5.28 | 6.46 |

| Benzo[a]naphtho[1,2-l]naphthacene | BaN12lNap | 378 | 30 | 4.05 | 6.97 |

| Benzo[a]naphtho[2,1-j]naphthacene | BaN21jNap | 378 | 30 | 3.95 | 7.00 |

| Benzo[b]naphtho[1,2-k]chrysene | BbN12kC | 378 | 30 | 3.89 | 7.00 |

| Benzo[b]naphtho[2,1-k]chrysene | BbN21kC | 378 | 30 | 3.89 | 6.91 |

| Benzo[c]naphtho[2,1-p]chrysene | BcN21pC | 378 | 30 | 5.49 | 5.46 |

| Dibenzo[a,c]pentacene | DBacPen | 378 | 30 | 4.57 | 6.25 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pentacene | DBalPen | 378 | 30 | 3.89 | 6.93 |

| Heptaphene | Hepta | 378 | 30 | 3.90 | 6.87 |

| Dibenzo[b,n]picene | DBbnPic | 378 | 30 | 3.90 | 6.95 |

| Dibenzo[c,m]pentaphene | DBcmPenta | 378 | 30 | 3.90 | 7.10 |

| Naphtho[2,3-c]pentaphene | N23cPenta | 378 | 30 | 4.01 | 6.96 |

| Phenanthro[1,2-b]chrysene | Phe12bC | 378 | 30 | 4.28 | 7.08 |

| Phenanthro[2,1-b]chrysene | Phe21bC | 378 | 30 | 3.89 | 6.97 |

| Phenanthro[4,3-b]chrysene | Phe43bC | 378 | 30 | 5.33 | 6.54 |

| Phenanthro[9,10-b]chrysene | Phe910bC | 378 | 30 | 4.98 | 7.04 |

| Phenanthro[3,4-b]triphenylene | Phe34bTriPhe | 378 | 30 | 5.47 | 5.28 |

| Phenanthro[9,10-b]triphenylene | Phe910bTriPhe | 378 | 30 | 5.95 | 6.04 |

| Tribenzo[a,c,j]naphthacene | TriBacjNap | 378 | 30 | 4.77 | 7.07 |

| Trinaphthylene | TriNaph | 378 | 30 | 4.51 | 7.01 |

| Eight-Ring PAHs | |||||

| Truxene | Trux | 342 | 24 | 4.26 | 5.99 |

| Benzo[a]coronene | BaCor | 350 | 28 | 3.89 | 6.17 |

| Benzo[pqr]naphtho[8,1,2-bcd]perylene | BpqrN812bcdPer | 350 | 28 | 4.26 | 6.13 |

| Phenanthro[5,4,3,2-abcde]perylene | Phe5432abcdePer | 350 | 28 | 3.89 | 6.16 |

| Pyranthrene | Pyrant | 376 | 30 | 3.94 | 6.39 |

| Tribenzo[a,cd,lm]perylene | TriBacdlmPer | 376 | 30 | 5.58 | 6.21 |

Instrumentation and chromatographic columns

NPLC-UV was performed using a liquid chromatograph (1200 series, Agilent Technologies, Avondale, PA) coupled to a UV-vis detector (UV2000, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MS). The LC system was equipped with a gradient pump (G1311A) a degasser (G1322A) and an auto sampler (G1329A). The instrument was computer controlled using commercial software (Chromeleon, Thermo Scientific). Separations were carried out on an NH2 analytical column purchased from Waters (Milford, MA) with the following characteristics: 25.0 cm length, 4.6 mm inner diameter, and 5 µm average particle diameters.

Methods

Thickness Calculations

The procedure for calculating the thickness (T) dimension has been described in detail previously [25, 26]. Typically, non-substituted PAHs and MePAHs with T ≈ 3.90 Å and T ≈ 4.20 Å, respectively, are considered to be planar molecules. As the T value increases, the degree of non-planarity increases for the PAH structure.

NPLC retention index data

NPLC retention index values (log I) were calculated according to Eq. (1) with the following index markers: (2) Naph, (3) Phe, (4) BaA, (5) BbC, (6) DBbkC, (7) BbN12kC [26].

| (1) |

R is the corrected retention volume, x represents the solute, and n and n + 1 represent the lower and higher eluting PAH standards. All retention index data was obtained at room temperature using the NH2 analytical column with a mobile phase of 98 % n-hexane and 2 % DCM with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min except for the seven-ring MM 352 Da, seven-ring MM 378 Da isomer group, and the eight-ring PAHs (80 % n-hexane and 20 % DCM). Previous studies have investigated the retention behavior of PAHs on NH2 stationary phase using log I values as their basis for retention indices using index markers 2 – 5 [26, 6]. DBahP was used as the six-ring index marker because of a lack of reference standard at that time for DBbkC. DBbkC and BbN12kC represent the six-ring and seven-ring, respectively, of the series of cata-condensed PAHs used as retention standards (Fig. S1). The log I values are based on three chromatographic runs obtained from reference standards. The standard deviation of log I values was equal to or less than ± 0.02. Baseline resolution of two components could be achieved with a difference of ~0.08 log I units on the NH2 analytical column.

Statistical t-test calculations

The method for calculating statistical t-test for linear correlations between L/B and T has been described in detail previously using Eq. (2) [27, 28]:

| (2) |

where r is the correlation coefficient, df is the degrees of freedom (n − 2), and n is the number of data points. Based on the df, the correlation coefficient shows a significant linear trend if the calculated tcal value is greater than the critical t-test value (tcrit). These statistical calculations will be used in the results and discussion section to correlate the NPLC retention behavior of isomeric PAHs and their structural non-planarity (T).

Results and Discussion

The NPLC retention indices (log I), molecular mass (MM), number of aromatic carbons, and thickness (T) values for the two-ring and three-ring, four-ring, five-ring, six-ring, and seven-ring and eight-ring PAHs are summarized in Tables 1 – 5, respectively. The retention indices in Tables 1 – 5 represent the most extensive compilation of NPLC retention data for PAHs on the NH2 phase to be published to date. The log I values reported here and the values from the original papers by Wise et al. [6, 10, 11, 22] discussed previously are generally in agreement relative to elution orders. However, because of the improvements in LC packing materials (10 µm irregular particles vs. 5 µm spherical particles), the analytical column used to generate the log I data in this study is much more efficient. Thus, PAHs with differences in retention indices of 0.07 – 0.10 log I are baseline resolved in the current study whereas in the original studies a difference of 0.10 to 0.12 log I units was generally required to separate two PAHs [22].

Since the original studies [10, 14, 22], researchers have reported retention behavior for a very limited number of PAHs (especially isomers) with the following polar functionalized stationary phases: NH2 [15, 29], triamine [30, 31], silica [30], alumina [30], 2,4-dinitroanilinooctaylsilica [31], 2,3,6-trinitroanillinooctylsilica [31], aminocyano [15, 32], dihydroxypropyl propyl ether [33], nitrophenyl [32], poly(4-vinylpyridine)-grafted silica [34], 3-(2,4-Dinitroanilino)propyl [30, 31, 35], and hypercrosslinked polystyrene [35]. Despite these additional polar stationary phases, the NH2 phase has been the predominant phase used for NPLC to isolate isomeric PAHs based on the number of aromatic carbon atoms [6, 7, 9]. Herein, we investigate this correlation by plotting the log I averages vs. the total number of aromatic carbon atoms in Fig. 1a. The error bars represent the standard deviation for the log I averages, which demonstrate that the retention behavior varies for PAHs with the same number of aromatic carbon atoms. This correlation is better illustrated in Fig. 1b, which plots the log I values vs. the total number of aromatic carbon atoms for each of the 124 unsubstituted parent PAHs. The MePAHs provided similar results as the unsubstituted parent PAHs, and the corresponding plots are provided in Figs. S2a and S2b. Differences among the retention of isomeric PAHs or MePAHs on the NH2 phase may be due to differences in molecular shape and/or non-planarity, which will be discussed in the following sections.

Fig 1.

Plots of the number of aromatic carbon atoms vs. the average log I value for the PAHs (a) and the log I value for each PAH (b). The uncertainty listed with each value is the standard deviation for the average log I value for each set of aromatic carbon atoms. Plot of the number of aromatic carbon atoms vs. the average log I and T value for the six-ring and seven-ring PAHs (c). Plot of the number of aromatic carbon vs. the average log I value for the dibenzopyrene and dibenzofluoranthene backbone isomer subsets (d).

In this study, 85 of the 124 parent PAHs included in this study have planar molecular structures, as indicated by the T parameter (T = 3.88 Å to 4.24 Å). The remaining PAHs have various degrees of non-planarity within the following ranges for T: T = 4.25 Å to 5.00 Å (27 PAHs), T = 5.01 Å to 5.50 Å (12 PAHs), and T > 5.50 Å (10 PAHs). As shown in Fig. 1b, three of the five PAHs with the highest degree of non-planarity (T > 5.50 Å) are less retentive than the PAHs with the same number of aromatic carbon atoms and T < 5.50 Å. The four isomeric groups of PAHs with 22, 24, 26, and 30 aromatic carbon atoms are plotted in Fig. 1c using the T parameter as a third dimension (size of the circle) to illustrate the influence of non-planarity on the retention behavior of PAHs. One of the isomer groups included in Fig. 1c is the six-ring PAHs with MM 302 Da (24 aromatic carbons), which primarily consist of two structural subsets: pyrene backbone (10 isomers) and fluoranthene backbone (12 isomers). The pyrene backbone for the MM 302 Da isomers consists of four benzene rings and the fluoranthene backbone consists of three benzene rings and one cyclopenta-1,3-diene ring. Based on the MM 302 Da isomer structure schemes shown in Fig. S3a and S3b, the average log I values for the PAHs are plotted vs. the total number of aromatic carbon atoms in Fig. 1d. In each case, the fluoranthene backbone PAHs were slightly more retentive than the pyrene backbone PAHs.

Two-ring and three-ring PAHs

The retention indices (log I) and T values for the two-ring and three-ring PAHs and MePAHs are summarized in Table 1. Ant and Phe are the two parent PAHs in this isomer group (Fig. S4). Although both isomers have the same T value, they are baseline resolved on the NH2 phase with Ant eluting first. Ant is the linear structure and Phe has the presence of a bay-region as shown in Fig S4, which is discussed in more detail in the next section. Similar studies have shown the importance of a bay-region for the retention behavior of PASH in RPLC on a polymeric C18 stationary phase [27]. In the case of MePAHs, the two of the four possible MeFlu isomers (MM 180 Da), three possible MeAnt isomers (MM 192 Da), and four of the five possible MePhe isomers (MM 192 Da) were evaluated on the NH2 phase (Fig S5, Fig S6, and Fig S7, respectively). The only isomer with MM of 192 Da with a non-planar structure is 4-MePhe with T = 4.69 Å, and it elutes slightly before the three other MePhe isomers, which all elute after Phe.

Four-ring PAHs

The retention indices (log I) and T values for the four-ring PAHs and MePAHs are summarized in Table 2. NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards of the four-ring PAHs are shown in Fig 2. The elution order among the four-ring PAH groups follows the increasing MM and number of aromatic carbon atoms of each isomer groups, i.e., MM 202 Da, MM 216 Da, and MM 228 Da. The three MM 202 Da isomers are nearly baseline resolved, while the three MM 216 Da isomers co-elute. NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards of the MeFluor and MePyr isomers are shown in Fig. S8 and Fig. S9, respectively. MeFluor and MePyr isomers have similar retention behaviors within the group due to their planar structures (T ≈ 4.21 Å). Comparisons with their parent PAH, i.e., Fluor and Pyr, reveal some differences in their retention behavior. Pyr elutes at log I of 3.44 and the three MePyr elute with log I values ranging from 3.38 to 3.43 while Fluor has a log I value of 3.51 and the four MeFluor elute later with log I values ranging from 3.57 to 3.65.

Table 2.

NPLC retention indices for the four-ring PAHs.

| PAHs | Abbreviations |

MM (Da) |

No. of Aromatic Carbon |

Thickness (Å) |

Log I NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acephenanthrene | Acephe | 202 | 16 | 3.89 | 3.59 |

| Fluoranthene | Fluor | 202 | 16 | 3.88 | 3.51 |

| 1-Methylfluoranthene | 1-MeFluor | 216 | 16 | 4.22 | 3.63 |

| 3-Methylfluoranthene | 3-MeFluor | 216 | 16 | 4.20 | 3.65 |

| 7-Methylfluoranthene | 7-MeFluor | 216 | 16 | 4.22 | 3.57 |

| 8-Methylfluoranthene | 8-MeFluor | 216 | 16 | 4.20 | 3.59 |

| Pyrene | Pyr | 202 | 16 | 3.89 | 3.44 |

| 1-Methylpyrene | 1-MePyr | 216 | 16 | 4.20 | 3.43 |

| 2-Methylpyrene | 2-MePyr | 216 | 16 | 4.20 | 3.38 |

| 4-Methylpyrene | 4-MePyr | 216 | 16 | 4.21 | 3.42 |

| 7H-Benzo[c]fluorene | 7H-BcF | 216 | 16 | 4.24 | 3.72 |

| 11H-Benzo[a]fluorene | 11H-BaF | 216 | 16 | 4.24 | 3.68 |

| 11H-Benzo[b]fluorene | 11H-BbF | 216 | 16 | 4.24 | 3.73 |

| Benzo[a]anthracene | BaA | 228 | 18 | 3.89 | 4.00 |

| 1-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 1-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 5.04 | 3.98 |

| 2-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 2-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.21 | 4.06 |

| 3-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 3-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.21 | 4.08 |

| 4-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 4-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.22 | 4.08 |

| 5-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 5-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.22 | 4.05 |

| 6-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 6-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.21 | 4.15 |

| 7-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 7-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.57 | 4.17 |

| 8-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 8-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.21 | 4.02 |

| 9-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 9-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.20 | 4.06 |

| 10-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 10-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.20 | 4.12 |

| 11-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 11-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 4.22 | 3.96 |

| 12-Methylbenzo[a]anthracene | 12-MeBaA | 242 | 18 | 5.16 | 3.97 |

| Benzo[c]phenanthrene | BcPhe | 228 | 18 | 4.99 | 3.66 |

| 1-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 1-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.94 | 3.60 |

| 2-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 2-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.18 | 3.77 |

| 3-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 3-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.00 | 3.76 |

| 4-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 4-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.39 | 3.74 |

| 5-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 5-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.28 | 3.73 |

| 6-Methylbenzo[c]phenanthrene | 6-MeBcPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.05 | 3.69 |

| Chrysene | Chr | 228 | 18 | 3.92 | 4.00 |

| 1-Methylchrysene | 1-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 4.22 | 4.11 |

| 2-Methylchrysene | 2-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 4.20 | 4.12 |

| 3-Methylchrysene | 3-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 4.20 | 4.12 |

| 4-Methylchrysene | 4-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 5.01 | 4.05 |

| 5-Methylchrysene | 5-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 4.97 | 4.04 |

| 6-Methylchrysene | 6-MeChr | 242 | 18 | 4.22 | 4.11 |

| Triphenylene | TriPhe | 228 | 18 | 4.37 | 4.10 |

| 1-Methyltriphenylene | 1-MeTriPhe | 242 | 18 | 5.19 | 4.08 |

| 2-Methyltriphenylene | 2-MeTriPhe | 242 | 18 | 4.18 | 4.15 |

| Naphthacene | Nap | 228 | 18 | 3.89 | 3.92 |

Fig 2.

NPLC separation of the four-ring PAH isomers with MM 202 Da, 216 Da, and 228 Da on the NH2 stationary phase

In the case of the cata-condensed MM 228 Da isomers, BaA and Chr co-elute but are resolved from the remaining three isomers, which are baseline resolved. PAHs with similar T values would be expected to have similar retention behaviors on the NH2 stationary phase. BaA, Chr, and Nap are the three planar PAHs with MM 228 Da. Similar to the retention behaviors of Ant and Phe, the linear isomer Nap elutes first followed by BaA and Chr that have bay-regions. BcPhe and TriPhe are non-planar with T values of 4.99 and 4.37 Å, respectively. BcPhe elutes earlier than the planar PAHs due to its non-planarity. TriPhe elutes last among the five MM 228 Da isomers despite the moderately non-planar structure but it does have three bay-regions in the structure. A plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T for the five MM 228 Da isomers is shown in Fig S10 with a correlation coefficient of r = −0.70, which provides a tcal value of 1.71 (tcrit = 3.18, α = 0.05, n = 5) indicating that there is not a significant linear trend between PAH retention and T values [36].

In the case of the 26 methyl-substituted four-ring cata-condensed PAHs (MM 242 Da), a plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T is shown in Fig. 3a with a correlation coefficient of r = −0.79, which provides a tcal value of 6.21 (tcrit = 2.07, α = 0.05, n = 26) indicating that there is a significant linear trend between the 26 cata-condensed MePAH retention and T values [36]. Based on the log I values reported in Table 2, non-planarity does play a significant role in the retention behavior of MePAHs on the NH2 stationary phase. Two examples of the importance of non-planarity are illustrated with BcPhe and Chr, their molecular structures are shown in Fig. 3b. The NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual standards of BcPhe and six MeBcPhe isomers are shown in Fig 3c. 1-MeBcPhe elutes prior to BcPhe on the NH2 stationary phase. This early elution behavior can be attributed to the higher degree of non-planarity as indicated by the larger T value (T = 5.94 Å). Similar results were obtained for the MeBaA isomers, where 1-Me (T = 5.04 Å) and 12-MeBaA (T = 5.16 Å) eluted prior to BaA. Of the cata-condensed four-ring MePAH isomers, the six MeChr isomers provided the best correlation for their retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T providing a correlation coefficient of r = −0.99 and a tcal value of 14.14 indicating that there is a significant linear trend (tcrit = 2.78, α = 0.05, n = 6) [36]. The NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual MeChr standards are shown in Fig. 3d. The earlier elution for 4-Me and 5-MeChr in comparison to the other four MeChr isomers can be explained by the larger T values of 4.97 Å and 5.01 Å, respectively. NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards of the MeBaA and MeTriPhe isomers are shown in Fig. S11 and Fig. S12, respectively.

Fig 3.

(a) Plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase versus T values for the 26 methyl-substituted four-ring cata-condensed PAHs. (b) Molecular structures of BcPhe and Chr and their methyl-substitution position numbering. (c) NPLC separation of BcPhe and six MeBcPhe isomers on the NH2 stationary phase. (d) NPLC separation of Chr and six MeChr isomers on the NH2 stationary phase

Five-ring PAHs

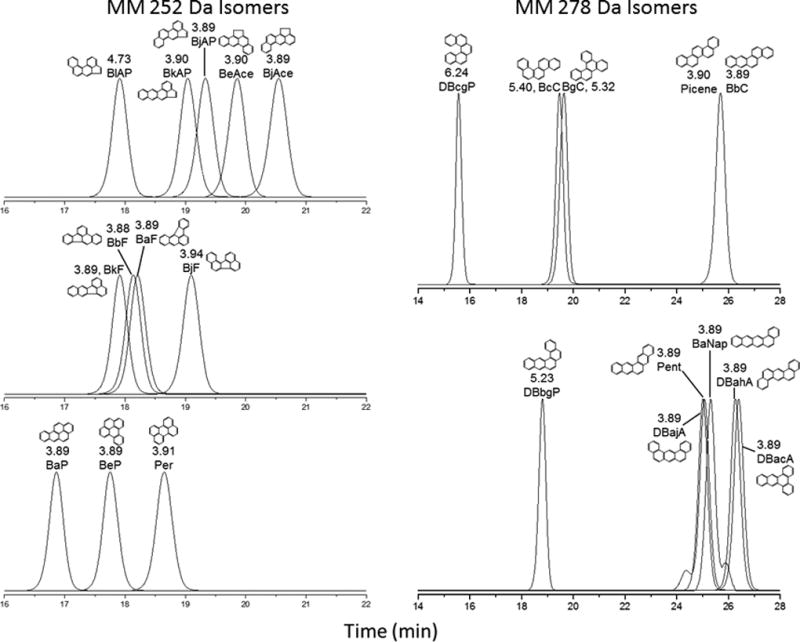

The retention indices (log I) and T values for the five-ring PAHs and MePAHs are summarized in Table 3. NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards of the 12 five-ring MM 252 Da PAHs and 11 five-ring MM 278 Da PAHs are shown in Fig. 4. In the case of the MM 252 Da isomers, the T values for the MM 252 Da isomers are ~ 3.90 Å indicating planarity except for BiAcep (4.73 Å). Because of the planarity of this PAH isomer group, their retention on the NH2 stationary phase and T values did not provide a significant linear correlation (r = 0.09, data not shown).

Table 3.

NPLC retention indices for the five-ring PAHs.

| PAHs | Abbreviations |

MM (Da) |

No. of Aromatic Carbon |

Thickness (Å) |

Log I NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzo[ghi]fluoranthene | BghiF | 226 | 18 | 3.88 | 3.70 |

| Cyclopenta[cd]pyrene | CPcdP | 226 | 18 | 3.89 | 3.95 |

| Benz[e]aceanthrylene | BeAce | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.58 |

| Benz[j]aceanthrylene | BjAce | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.64 |

| Benz[j]acephenanthrylene | BjAcep | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.54 |

| Benz[k]acephenanthrylene | BkAcep | 252 | 20 | 3.90 | 4.51 |

| Benz[l]acephenanthrylene | BlAcep | 252 | 20 | 4.73 | 4.50 |

| Benzo[a]fluoranthene | BaF | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.44 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | BbF | 252 | 20 | 3.88 | 4.43 |

| Benzo[j]fluoranthene | BjF | 252 | 20 | 3.94 | 4.52 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | BkF | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.41 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | BeP | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.40 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | BaP | 252 | 20 | 3.89 | 4.30 |

| 1-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 1-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.20 | 4.42 |

| 2-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 2-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.21 | 4.37 |

| 3-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 3-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.22 | 4.45 |

| 4-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 4-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.21 | 4.38 |

| 5-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 5-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.22 | 4.39 |

| 6-Methylbenzo[pyrene | 6-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.36 | 4.52 |

| 7-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 7-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.22 | 4.40 |

| 8-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 8-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.20 | 4.42 |

| 9-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 9-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.20 | 4.41 |

| 10-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 10-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.98 | 4.36 |

| 11-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 11-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.89 | 4.36 |

| 12-Methylbenzo[a]pyrene | 12-MeBaP | 266 | 20 | 4.21 | 4.42 |

| Perylene | Per | 252 | 20 | 3.91 | 4.48 |

| 1-Methylperylene | 1-MePer | 266 | 20 | 5.27 | 4.50 |

| 2-Methylperylene | 2-MePer | 266 | 20 | 4.46 | 4.49 |

| 3-Methylperylene | 3-MePer | 266 | 20 | 4.44 | 4.59 |

| Benzo[a]naphthacene | BaNap | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 4.97 |

| Benzo[b]chrysene | BbC | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 5.00 |

| Benzo[c]chrysene | BcC | 278 | 22 | 5.39 | 4.56 |

| Benzo[g]chrysene | BgC | 278 | 22 | 5.32 | 4.56 |

| Dibenz[a,c]anthracene | DBacA | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 5.04 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | DBahA | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 5.03 |

| Dibenz[a,j]anthracene | DBajA | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 4.96 |

| Dibenzo[b,g]phenanthrene | DBbgP | 278 | 22 | 5.23 | 4.50 |

| Dibenzo[c,g]phenanthrene | DBcgP | 278 | 22 | 6.24 | 4.16 |

| Pentaphene | Pen | 278 | 22 | 3.89 | 4.96 |

| Picene | Pic | 278 | 22 | 3.90 | 5.00 |

| 1-Methylpicene | 1-MePic | 292 | 22 | 5.39 | 5.03 |

| 2-Methylpicene | 2-MePic | 292 | 22 | 4.20 | 5.12 |

| 3-Methylpicene | 3-MePic | 292 | 22 | 4.20 | 5.12 |

| 6-Methylpicene | 6-MePic | 292 | 22 | 5.56 | 5.10 |

| 13-Methylpicene | 13-MePic | 292 | 22 | 5.42 | 5.06 |

Fig 4.

NPLC separation of the 12 MM 252 Da PAH isomers and the 11 MM 278 Da isomers on the NH2 stationary phase

In the case of the five-ring MM 278 Da PAH isomers (cata-condensed), non-planarity was expected to play an important role in their retention behaviors based on their T values and previous discussions including the four-ring cata-condensed PAHs. BbC, Pic, DBajA, Pent, BaNap, DBahA, and DBacA are planar with T values of ≈ 3.89 Å. DBcgP, DBbgP, BcC, and BgC are non-planar with T values ranging from 5.23 Å to 6.24 Å. The chromatograms in Fig. 4 clearly indicate the effect of non-planarity on the retention behavior. The seven planar isomers elute within 24 min – 27 min, while the non-planar isomers (T ≈ 5.30 Å) elute earlier at 18.5 min – 20 min and the highly non-planar isomer DBcgP (T ≈ 6.24 Å), elutes at ~15.5 min. The correlation of retention on the NH2 phase and T value for the 11 MM 278 Da isomers is shown in Fig. 5a with a correlation coefficient of r = −0.99. The tcal value is 23.45 (tcrit = 2.16, α = 0.05, n = 11) indicating that there is a significant linear trend between the retention of cata-condensed five-ring PAH isomers and T values [36].

Fig 5.

Plots of retention on the NH2 stationary phase versus T values for the a) 11 MM 278 Da PAH isomers, b) 25 MM 302 Da PAH isomers, c) 17 MM 328 Da PAH isomers, and d) 20 MM 378 Da PAH isomers

A number of five-ring MePAH isomer sets were investigated including two peri-condensed isomer sets (12 MeBaP and 3 MePer) and one cata-condensed MePAH isomer set (5 MePic). NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards for these isomers are shown in Fig. S13, Fig. S14, and Fig. S15, respectively. In the case of the peri-condensed isomer sets, the MePAH isomers with the methyl group located in the bay-region of the structure provided the highest degree of non-planarity with T ≥ 4.89 Å (1-MePer, 10-MeBaP, and 11-MeBaP). Similar behaviors were observed for 1-Me, 6-Me, and 13-MePic with T values of 5.39 Å, 5.56 Å, and 5.42 Å, respectively. In all cases, the MePAHs eluted later then the parent PAH and the non-planar MePAH eluted earlier than the other MePAH isomers (exception is 1-MePer).

Six-ring PAHs

The retention indices (log I) and T values for the six-ring PAHs are summarized in Table 4. The six-ring PAHs consist of the following isomer groups: (1) MM 276 Da; (2) MM 302 Da; and (3) MM 328 Da. NPLC chromatograms obtained from individual reference standards of the MM 276 Da PAH isomers are shown in Fig. S16. A large number of non-planar PAH isomers are included in the MM 302 Da and MM 328 Da groups with seven isomers (T ≥ 4.84 Å) and six isomers (T ≥ 4.85 Å), respectively. In addition, the MM 328 Da PAH isomers represent the group with the largest differences in T values among all isomer sets investigated with T ranging from 3.88 Å (DBalNap) to 7.41 Å (Phe34cPhe).

Table 4.

NPLC retention indices for the six-ring PAHs.

| PAHs | Abbreviations |

MM (Da) |

No. of Aromatic Carbon |

Thickness (Å) |

Log I NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthanthrene | Anth | 276 | 22 | 3.88 | 4.66 |

| Benzo[ghi]perylene | BghiPer | 276 | 22 | 3.89 | 4.75 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | I123cdP | 276 | 22 | 3.88 | 4.89 |

| Benzo[a]perylene | BaPer | 302 | 24 | 5.47 | 4.97 |

| Benzo[b]perylene | BbPer | 302 | 24 | 4.84 | 5.49 |

| Dibenzo[a,e]pyrene | DBaeP | 302 | 24 | 4.19 | 5.43 |

| Dibenzo[a,h]pyrene | DBahP | 302 | 24 | 3.90 | 5.35 |

| Dibenzo[a,i]pyrene | DBaiP | 302 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.31 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | DBalP | 302 | 24 | 5.17 | 4.88 |

| Dibenzo[e,l]pyrene | DBelP | 302 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.45 |

| Dibenzo[a,e]fluoranthene | DBaeF | 302 | 24 | 3.90 | 5.39 |

| Dibenzo[a,f]fluoranthene | DBafF | 302 | 24 | 3.97 | 5.40 |

| Dibenzo[a,k]fluoranthene | DBakF | 302 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.35 |

| Dibenzo[b,e]fluoranthene | DBbeF | 302 | 24 | 4.64 | 5.14 |

| Dibenzo[b,k]fluoranthene | DBbkF | 302 | 24 | 3.90 | 5.37 |

| Dibenzo[j,l]fluoranthene | DBjlF | 302 | 24 | 4.41 | 5.48 |

| Dibenzo[de,mn]naphthacene | DBNap | 302 | 24 | 4.89 | 5.53 |

| Naphtho[1,2-a]pyrene | N12aP | 302 | 24 | 5.13 | 4.91 |

| Naphtho[1,2-e]pyrene | N12eP | 302 | 24 | 5.15 | 4.92 |

| Naphtho[2,1-a]pyrene | N21aP | 302 | 24 | 4.19 | 5.32 |

| Naphtho[2,3-a]pyrene | N23aP | 302 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.27 |

| Naphtho[2,3-e]pyrene | N23eP | 302 | 24 | 4.41 | 5.35 |

| Naphtho[1,2-b]fluoranthene | N12bF | 302 | 24 | 3.90 | 5.44 |

| Naphtho[1,2-k]fluoranthene | N12kF | 302 | 24 | 3.91 | 5.51 |

| Naphtho[2,1-b]fluoranthene | N21bF | 302 | 24 | 4.92 | 5.15 |

| Naphtho[2,3-b]fluoranthene | N23bF | 302 | 24 | 3.89 | 5.39 |

| Naphtho[2,3-j]fluoranthene | N23jF | 302 | 24 | 3.93 | 5.52 |

| Naphtho[2,3-k]fluoranthene | N23kF | 302 | 24 | 3.90 | 5.39 |

| Benzo[b]picene | BbPic | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.03 |

| Benzo[c]picene | BcPic | 328 | 26 | 3.90 | 5.78 |

| Benzo[c]pentaphene | BcPen | 328 | 26 | 3.90 | 6.05 |

| Benzo[h]pentaphene | BhPen | 328 | 26 | 4.85 | 6.05 |

| Dibenzo[a,j]naphthacene | DBajNap | 328 | 26 | 3.95 | 6.03 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]naphthacene | DBalNap | 328 | 26 | 3.88 | 6.06 |

| Dibenzo[c,p]chrysene | DBcpC | 328 | 26 | 5.62 | 4.97 |

| Dibenzo[g,p]chrysene | DBgpC | 328 | 26 | 6.15 | 4.84 |

| Dibenzo[b,k]chrysene | DBbkC | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.00 |

| Dibenzo[a,c]naphthacene | DBacNap | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.04 |

| Naphtho[1,2-b]triphenylene | N12bTriPhe | 328 | 26 | 4.14 | 6.04 |

| Naphtho[1,2-a]naphthacene | N12aNap | 328 | 26 | 5.00 | 5.45 |

| Naphtho[2,1-a]naphthacene | N21aNap | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.02 |

| Naphtho[1,2-b]chrysene | N12bC | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 6.08 |

| Naphtho[2,3-g]chrysene | N23gC | 328 | 26 | 5.43 | 5.39 |

| Hexaphene | Hexa | 328 | 26 | 3.89 | 5.97 |

| Phenanthro[3,4-c]phenanthrene | Phe34cPhe | 328 | 26 | 7.41 | 4.89 |

NPLC chromatograms obtained on the NH2 phase with individual reference standards of the 25 six-ring MM 302 Da PAHs are shown in Fig. 6. Wise et al. [6] reported log I values for 19 isomers of MM 302 Da using different retention marker PAHs for the six-ring and seven-ring markers. The elution order of the 19 isomers in the original report and this study are similar. Of particular interest is the fact that 6 of the 8 non-planar isomers elute distinctively before (≤ 29 min) the remaining 18 investigated isomers (≥ 30 min) investigated. The other two nonplanar isomers, BbPer and DBNap, showed the highest affinity for the NH2, which could be influence by the presence of bay-regions in their molecular structures (1 and 2, respectively). In addition to the strongly non-planar isomers (T ≥ 4.84 Å), there is a group of five MM 302 Da isomers that are moderately non-planar with T values ranging from 4.19 Å (DBaeP and N21aP) to 4.64 Å (DBbeF). With the exception of DBbeF, the moderately non-planar PAHs elute with the planar MM 302 Da isomers (T ≈ 3.90 Å) between 30 – 37 min. A plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T for the MM 302 Da isomers is shown in Fig. 5b. A correlation coefficient of r = −0.71 and a tcal value of 4.80 (tcrit = 2.08, α = 0.05, n = 25) indicates the existence of a linear trend. Similar to the MM 278 Da isomers, the general trend for elution on the NH2 phase for the MM 302 Da isomers is influenced by structure non-planarity.

Fig 6.

NPLC separation of the 25 MM 302 Da PAH isomers on the NH2 stationary phase

NPLC chromatograms obtained on the NH2 phase with individual reference standards of the 17 six-ring MM 328 Da cata-condensed PAHs are shown in Fig. 7. For this isomer set, 5 of the 6 non-planar isomers elute (≤ 35 min) distinctively before the remaining 12 isomers (≥ 40 min). The extreme non-planarity of Phe34cPhe, DBgpC, and DBcpC resulted in similar log I values as the MM 276 Da and the non-planar MM 302 Da isomers. In the case of DBgpC and Phe34cPhe, their non-planarity has been used extensively to characterize C18 stationary phases in RPLC [37–39]. BhPen with a T = 4.85 Å elutes ~ 15 min later than N12aNap with a T = 5.00 Å. Based on previous discussions, the three bay-regions in the molecular structure for BhPen may influence the later retention than N12aNap with no bay-regions. Similar observations were made for the MM 302 Da isomers of BbPer (T = 4.84 Å) and DBNap (T = 4.89 Å), which elute later than N21bF (T = 4.92 Å). A plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T for the MM 328 Da isomers is shown in Fig. 5c. The plot provided a correlation coefficient of r = −0.91 and a tcal value of 8.60 (tcrit = 2.13, α = 0.05, n = 17) indicating a clear linear trend.

Fig 7.

NPLC separation of the 17 MM 328 Da PAH isomers on the NH2 stationary phase

Seven-ring and eight-ring PAHs

The retention indices (log I) and T values for the seven- and eight-ring PAHs are summarized in Table 5. These isomer groups consisted of Cor (MM 300 Da), eight MM 326 Da isomers, Trux (MM 342 Da), three MM 350 Da isomers, three MM 352 Da isomers, two MM 376 Da isomers, and 20 MM 378 Da isomers. NPLC chromatograms obtained on the NH2 phase with individual reference standards of these PAHs are shown in Fig. S17 – Fig. S20. Cor was the only MM 300 Da isomer included in this study. A total of eight MM 326 Da isomers were available for this study and they can be divided into two sub-groups based on the perylene and fluoranthene structural backbone. The five perylene-based PAHs elute before the three fluoranthene-based PAHs. Additional MM 326 Da reference standards are required to fully explore this trend in more detail. In the case of the perylene-based MM 326 Da isomers, DBcdlmPer elutes at ~28 min while the remaining four isomers elute between 37 – 42 min. The three fluoranthene-based isomers are baseline resolved over a 10 min time interval. No correlation of retention vs T was observed.

The molecular structures of the seven-ring cata-condensed PAH isomers with MM 378 Da are shown in Fig. S21. This isomer group represents the largest number of non-planar isomers in this study with 10 isomers, which have T values ranging from 4.28 Å to 5.95 Å. A plot of retention on the NH2 stationary phase vs. T for the MM 378 Da isomers is shown in Fig. 5d. The plot provided a correlation coefficient of r = −0.74 and a tcal value of 6.71 (tcrit = 2.09, α = 0.05, n = 20) indicating that there is a significant linear trend. Similar to the MM 278 Da, MM 302 Da, MM 328 Da isomers, the general trend for elution on the NH2 phase for the MM 378 Da isomers is influenced by non-planarity. The 10 non-planar isomers can be split into three subsets based on the same T values used in Fig. 1: (1) Phe12bC (4.28 Å), TriNaph (4.51 Å), DBacPen (4.57 Å), TriBacjNap (4.77 Å), and Phe910bC (4.98 Å); (2) BaN12jNap (5.28 Å), Phe 43bC (5.33 Å), Phe34bTriPhe (5.47 Å), and BcN21pC (5.49 Å); and 3) Phe910bTriPhe (5.95 Å).

DBacPen was the only PAH from subset 1 to elute earlier than the planar isomers. It is interesting to note that DBacPen has the fewest number of bay-regions (three) and has a linear structural backbone (Nap) with no additional benzene ring attachments. As discussed for the three and four-ring cata-condensed PAH isomers, these two structural features result in these PAHs being less retentive on the NH2 stationary phase. Of the four isomers in subset 2, BcN21pC and Phe34bTriPhe are less retentive than Phe43bC and BaN12jNap, which could be a result of the slight difference in T values (~0.14 Å). Phe910bTriPhe (subset 3) was expected to be less retentive than the PAHs in subset 2 based on the results for the non-planar five- and six-ring cata-condensed PAHs. However, Phe910bTriPhe eluted after Phe34bTriPhe and BcN21pC. Phe910bTriPhe and Phe34bTriPhe have similar molecular structure backbone except for the placement of one benzene ring, which results in Phe910bTriPhe having six bay-regions and Phe34bTriPhe having three bay-regions and one fj-region.

Conclusions

The results presented in this paper represent the most extensive investigation of NPLC retention behavior of PAHs and MePAHs on a polar stationary phase (i.e., the NH2 phase). The NPLC retention of PAHs on the NH2 phase is primarily based on the number of aromatic carbon atoms in the structure. In the case were there are differences in retention behavior, two main structure features are shown to influence the retention of PAHs on the NH2 phase. First, the non-planar isomers are less retentive than the planar isomers. Correlations between the non-planarity (T) of the MM 278 Da, MM 302 Da, MM 328 Da, and MM 378 Da isomers and their retention on the NH2 phase were reported with correlation coefficients ranging from r = −0.71 (MM 302 Da isomers) to r = −0.99 (MM 278 Da isomers). Second, the presence of a bay-region in the structure of isomeric PAHs resulted in the PAHs being more retentive on the NH2 phase. The retention data reported in this study will provide the basis for developing NPLC fractionation strategies to characterize complex PAH mixtures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

H. V. Hayes and A. D. Campiglia acknowledge financial support from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (Grant 231617-00). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of this organization.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

Certain commercial equipment or materials are identified in this paper to specify adequately the experimental procedure. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Canha N, Lopes I, Vicente ED, Vicente AM, Bandowe BAM, Almeida SM, et al. Mutagenicity assessment of aerosols in emissions from domestic combustion processes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016;23(11):10799–807. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson GM, Meyer BM, Portier RJ. Assessment of the toxic potential of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) affecting gulf menhaden (brevoortia patronus) harvested from waters impacted by the bp deepwater horizon spill. Chemosphere. 2016;145:322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza MR, da Silva FR, de Souza CT, Niekraszewicz L, Dias JF, Premoli S, et al. Evaluation of the genotoxic potential of soil contaminated with mineral coal tailings on snail helix aspersa. Chemosphere. 2015;139:512–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise SA, Sander LC, Schantz MM. Analytical methods for determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) - a historical perspective on the 16 US EPA priority pollutant PAHs. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2015;35(2–4):187–247. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2014.970291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poster DL, Schantz MM, Sander LC, Wise SA. Analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in environmental samples: A critical review of gas chromatographic (GC) methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;386(4):859–81. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise SA, Benner BA, Liu HC, Byrd GD, Colmsjö A. Separation and identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon isomers of molecular-weight 302 in complex-mixtures. Anal Chem. 1988;60(7):630–7. doi: 10.1021/ac00158a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wise SA, Benner BA, Byrd GD, Chesler SN, Rebbert RE, Schantz MM. Determination of polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons in a coal-tar standard reference material. Anal Chem. 1988;60(9):887–94. doi: 10.1021/ac00160a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise SA, Schantz MM, Benner BA, Hays MJ, Schiller SB. Certification of polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons in a marine sediment standard reference material. Anal Chem. 1995;67(7):1171–8. doi: 10.1021/ac00103a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regueiro J, Matamoros V, Thibaut R, Porte C, Bayona JM. Use of effect-directed analysis for the identification of organic toxicants in surface flow constructed wetland sediments. Chemosphere. 2013;91(8):1165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wise SA, Chesler SN, Hertz HS, Hilpert LR, May WE. Chemically-bonded aminosilane stationary phase for high-performance liquid-chromatographic separation of polynuclear aromatic-compounds. Anal Chem. 1977;49(14):2306–10. doi: 10.1021/ac50022a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May WE, Wise SA. Liquid-chromatographic determination of polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons in air particulate extracts. Anal Chem. 1984;56(2):225–32. doi: 10.1021/ac00266a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise SA, Benner BA, Chesler SN, Hilpert LR, Vogt CR, May WE. Characterization of the polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons from 2 standard reference material air particulate samples. Anal Chem. 1986;58(14):3067–77. doi: 10.1021/ac00127a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise SA, Deissler A, Sander LC. Liquid chromatographic determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon isomers of molecular weight 278 and 302 in environmental standard reference materials. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 1993;3(3):169–84. doi: 10.1080/10406639308047869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hertz HS, Brown JM, Chesler SN, Guenther FR, Hilpert LR, May WE, et al. Determination of individual organic-compounds in shale oil. Anal Chem. 1980;52(11):1650–7. doi: 10.1021/ac50061a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson P, Sadiktsis I, Holmback J, Westerholm R. Class separation of lipids and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in normal phase high performance liquid chromatography - a prospect for analysis of aromatics in edible vegetable oils and biodiesel exhaust particulates. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1360:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang ML, Getzinger GJ, Cooper EM, Clark BW, Garner LVT, Di Giulio RT, et al. Effect-directed analysis of elizabeth river porewater: Developmental toxicity in zebrafish (danio rerio) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33(12):2767–74. doi: 10.1002/etc.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marvin CH, McCarry BE, Lundrigan JA, Roberts K, Bryant DW. Bioassay-directed fractionation of pah of molecular mass 302 in coal tar-contaminated sediment. Sci Total Environ. 1999;231(2–3):135–44. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(99)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swistek M, Weber JV. A separative tool for analyzing heavy coal and petroleum residues - the extrography. Analusis. 1991;19(7):191–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilgenast E, Boczkaj G, Przyjazny A, Kaminski M. Sample preparation procedure for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in petroleum vacuum residue and bitumen. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;401(3):1059–69. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popl M, Dolansky V, Mostecky J. Influence of molecular-structure of aromatic-hydrocarbons on their adsorptivity on silica-gel. J Chromatogr. 1976;117(1):117–27. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)81072-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popl M, Dolansky V, Mostecky J. Influence of molecular-structure of aromatic-hydrocarbons on their adsorptivity on alumina. J Chromatogr. 1974;91:649–58. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)97945-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wise SA, Bonnett WJ, May WE. Normal- and reversed-phase liquid chromatographic separations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Dennis ABaAJ., editor. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons: Chemistry and biological effects. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press; 1980. pp. 791–806. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson WB, Hayes HV, Sander LC, Campiglia AD, Wise SA. Retention behavior of polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles and their alkyl-substituted derivatives via normal-phase liquid chromatography. Anal Bioanal chem. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0795-7. in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson WB, Hayes HV, Sander LC, Campiglia AD, Wise SA. Qualitative characterization of srm 1597a for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some methyl-substituted derivatives via normal-phase liquid chromatography and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0464-x. in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sander LC, Wise SA. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure Index, NIST Special Publication. Vol. 922. Washington, DC: 1997. [accessed 17.01.03]. ( https://www.nist.gov/mml/csd/special-publication-922-polycyclic-aromatic-hydrocarbon-structure-index) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wise SA, Sander LC, Jinno K, editors. Chromatographic separatiosn based on molecular recognition. Wiley-VCH; 1997. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson WB, Sander LC, de Alda ML, Lee ML, Wise SA. Retention behavior of isomeric polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1461:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.07.064. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson WB, Sander LC, de Alda ML, Lee ML, Wise SA. Retention behavior of alkyl-substituted polycyclic aromatic sulfur heterocycles in reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1461:120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.07.065. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2016.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun M, Feng JJ, Luo CN, Liu X, Jiang SX. Quinolinium ionic liquid-modified silica as a novel stationary phase for high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(11):2651–8. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7680-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grizzle PL, Thomson JS. Liquid chromatographic separation of aromatic hydrocarbons with chemically bonded (2,4-dinitroanilinopropyl)silica. Anal Chem. 1982;54(7):1071–8. doi: 10.1021/ac00244a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson JS, Reynolds JW. Separation of aromatic hydrocarbons using bonded-phase charge-transfer liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 1984;56(13):2434–41. doi: 10.1021/ac00277a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lubcke-von Varel U, Streck G, Brack W. Automated fractionation procedure for polycyclic aromatic compounds in sediment extracts on three coupled normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography columns. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1185(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubke M, Lequere JL, Barron D. Normal-phase high-performance liquid-chromatography of volatile compounds - selectivity and mobile-phase effects on polar bonded silica. J Chromatogr A. 1995;690(1):41–54. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)01048-j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gautam UG, Shundo A, Gautam MP, Takafuji M, Ihara H. High retentivity and selectivity for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with poly(4-vinylpyridine)-grafted silica in normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1189(1–2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang P, Lucy CA. Retentivity, selectivity and thermodynamic behavior of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on charge-transfer and hypercrosslinked stationary phases under conditions of normal phase high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1437:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MJ, Miller JC. Statistics and chemometrics for analytical cehmistry. 6. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sander LC, Wise SA. Synthesis and characterization of polymeric C18 stationary phases for liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 1984;56(3):504–10. doi: 10.1021/ac00267a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sander LC, Wise SA. Shape selectivity in reversed-phase liquid chromatography for the separation of planar and non-planar solutes. J Chromatogr A. 1993;656(1–2):335–51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9673(93)80808-L. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sander LC, Wise SA. Determination of column selectivity toward polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J High Resolut Chromatogr. 1988;11(5):383–7. doi: 10.1002/jhrc.1240110505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.