Abstract

The assessment of binge ethanol-induced neuronal activation, using c-Fos immunoreactivity (IR) as a marker of neuronal activity, is typically accomplished via forced-ethanol exposure, such as intraperitoneal injection or gavage. Neuronal activity using a voluntary binge-like drinking model, such as “drinking-in-the-dark” (DID), has not been thoroughly explored. Additionally, studies assessing ethanol-elicited neuronal activation may or may not involve stereotaxic surgery, which could impact c-Fos IR. The experiments detailed herein aimed to assess the effects of voluntary binge-like ethanol consumption on c-Fos IR in brain regions implicated in ethanol intake in animals with and without surgery experience. Age-matched male C57BL/6J mice underwent either stereotaxic surgery (Study 1) or no surgery (Study 2). Then, mice experienced one 4-day DID cycle, tail blood samples were collected immediately after test conclusion on day 4, and mice were subsequently sacrificed. In each study, mice that drink ethanol were sorted into those that achieved binge-equivalent blood ethanol concentrations (BECs ≥ 80 mg/dl) versus those that did not. Relative to water-consuming controls, mice with BECs ≥ 80 mg/dl showed significantly elevated c-Fos IR in several brain regions implicated in neurobiological responses to ethanol. In general, the brain regions exhibiting binge-induced c-Fos IR were the same between studies, though differences were noted, highlighting the need for caution when interpreting ethanol-induced c-Fos IR when subjects have a prior history of surgery. Altogether, these results provide insight into the brain regions that modulate binge-like ethanol intake stemming from DID procedures among animals with and without surgery experience.

Keywords: c-Fos, drinking-in-the-dark (DID), voluntary consumption, binge, ethanol, surgery

Introduction

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines a binge episode as a 2-hour period in which men and women consume ≥ 5 or 4 alcoholic beverages, respectively, eliciting blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) exceeding 0.08% (80 mg/dL) (NIAAA, 2004). Several existing rodent models of binge drinking involve forced exposure techniques, such as intragastric gavage and intraperitoneal administration (i.p.), though these methods inherently fail to model voluntary consumption observed in humans. A well-developed preclinical model of voluntary binge-like ethanol consumption has been developed, called “drinking-in-the-dark” (DID), which promotes high levels of consumption and reliably generates BECs exceeding 80 mg/dL over a 4-day paradigm (Rhodes et al., 2005, Rhodes et al., 2007, Thiele and Navarro, 2014). Though most commonly utilized in mice, researchers have adapted the DID paradigm for use in rat studies (Bell et al., 2011, Holgate et al., 2017, Larraga et al., 2017). With DID procedures researchers have shown that several brain regions are implicated in modulation of binge-like ethanol intake, recruiting a variety of neurochemical systems (Sprow and Thiele, 2012). For example, in response to binge-like ethanol drinking, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) levels are increased or decreased, respectively, in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST; Pleil et al., 2015), CRF levels are increased within the central amygdala (CeA) and ventral tegmental area (VTA; Lowery-Gionta et al., 2012, Albrechet-Souza et al., 2015), NPY levels are reduced in the CeA (Sparrow et al., 2012), and orexin levels are reduced in the lateral hypothalamus (LH; Olney et al., 2015).

Numerous studies have measured ethanol administration-elicited neuronal activation via quantification of inducible transcription factors (ITFs), such as c-Fos (Curran and Morgan, 1995). The use of c-Fos expression has been useful for not only assessing neuronal activity in response to ethanol consumption and administration, but also to study phenotypes associated with increased risk of excessive consumption. For example, adolescent mice with a history of prenatal ethanol exposure exhibit reduced c-Fos activity in the infralimbic cortex (Fabio et al., 2013) while prenatal ethanol exposure reduces and elevates ethanol injection-primed c-Fos IR in the prelimbic cortex and VTA, respectively (Fabio et al., 2015). Brain mapping of nuclei involved in ethanol’s effects via quantification of ethanol-induced c-Fos expression has been studied using a variety of ethanol-exposure paradigms, though ethanol exposure at binge-like levels has most frequently been modeled via intragastric and i.p. administration techniques. For instance, researchers have shown that intragastrically-administered binge-like episodes increase c-Fos immunoreactivity (IR) in various brain regions including the CeA (Leriche et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2011), the locus coeruleus (LC), the A1–A2 cell groups, and adrenergic C1–C3 cell groups (Lee et al., 2011). Likewise, ethanol administered i.p. increases c-Fos IR in the LC and A2 subregion of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS; Thiele et al., 2000), Edinger-Westphal nucleus (EW; Chang et al., 1995, Turek and Ryabinin, 2005), and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), CeA, dBNST, and EW (Knapp et al., 2001).

Assessment of c-Fos induction following voluntary ethanol consumption in limited-access consumption or operant paradigms (Ryabinin et al., 2003) or chronic consumption in two-bottle choice paradigms (Li et al., 2010, Sajja and Rahman, 2013) indicates that voluntary consumption can region-specifically alter c-Fos expression. However, c-Fos IR resulting from DID-elicited binge-like ethanol drinking has not been examined in mice. This is a critical gap in the literature given the popular use of DID procedures in pre-clinical studies (Sprow and Thiele, 2012). Accordingly, the goal of the present study was to assess the effects of binge-like ethanol intake, using DID procedures, on neuronal activation in various brain regions implicated in alcohol use and abuse. Candidate regions for quantification included noradrenergic brainstem structures, extended amygdaloid structures (BNST, CeA, & basolateral amygdala (BLA)), the LH, and the EW, regions that have previously been shown to exhibit ethanol-induced c-Fos expression using other consumption or exposure paradigms. To this end, c-Fos IR in mice with BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl was compared to c-Fos IR from mice with BECs below 80 mg/dl and water-consuming control mice. BECs and tissue collection occurred following test conclusion (day 4), providing insight into patterns of neuronal activity present during experimental manipulations typically performed on day 4 of the DID procedure. Since preclinical studies assessing ethanol consumption may or may not utilize stereotaxic surgery procedures prior to testing, and given recent evidence that exposure to the anesthetic drug isoflurane impacts ethanol-induced c-Fos expression (Smith et al. 2016) we assessed binge-induced c-Fos expression in both surgery-naïve and surgery-exposed mice in two separate studies. Finally, we assessed tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)/c-Fos co-expression in the LC and A2 nucleus of the NTS among surgery-exposed mice to determine the percentage of noradrenergic cells activated within each region and to compare with one of our previous studies (Thiele et al., 2000) that examined similar labeling in rats receiving an ethanol injection.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (n=50, stock # 000664, Jackson Laboratory), 6 – 8 weeks old were housed in individual home cages with a room temperature maintained at 22°C and a 12:12 hour (hr) reverse light/dark cycle with lights off at 0830 hr. Prolab® RMH 3000 (Purina labDiet®; St. Louis, MO) and water were available ad libitum except where noted. All protocols were conducted under National Institute of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Voluntary consumption: “Drinking-in-the-Dark” Procedure

A four-day DID paradigm was used. Briefly, animal weights were collected 30 minutes prior to homecage water bottle removal. Beginning 3 hr into the dark cycle, homecage water bottles were removed and replaced with 10 mL plastic pipettes (calibrated to 0.1 mL) containing either unsweetened ethanol [20%, v/v; diluted from 95% (Decon Labs, King of Prussia, PA)] or tap water. Following the two hour free-access period, pipettes were removed and homecage water bottles were returned. Pipette volume was measured to the nearest 0.1 mL at homecage water bottle removal and replacement. Ethanol consumption was assessed as the difference in volume measured at the beginning of the session versus the end. On the fourth day tail blood samples were collected from each animal 2–4 minutes after ethanol or water access, and BECs from ethanol-consuming mice were assessed via an alcohol analyzer (Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA).

We elected to provide mice with 2 hours of access over all 4 days as opposed to 4 hours access on day 4 of the DID procedure as our lab has found that chemogenetic and pharmacological procedures often produce effects that subside within 2 hours (Navarro et al., 2016, Olney et al., 2017, Rinker et al., 2017), and despite the more limited access period, mice undergoing 2 hours of access achieve binge-equivalent BECs similar in magnitude to BECs achieved with 4 hours of access on day 4 (Olney et al., 2017).

Experimental Procedure

All mice experienced 1, 4-day DID cycle prior to sacrifice. Surgery-exposed and surgery-naïve cohorts were run as separate studies.

Surgery cohort

30 mice were weighed and anesthetized using a ketamine (66.7 mg/kg; Henry Schein, Dublin, OH) and xylazine (6.67 mg/kg) cocktail administered by i.p. injection. 0.1 mL 1% Lidocaine HCl (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) was subcutaneously applied above the skull. Green and red Retrobeads (0.2 – 0.3 μL/site; Lumafluor, Durham, NC), directed at ipsilateral BNST (AP +0.15, ML −1.00, DV −4.8; no angle) and VTA (AP −3.1, ML −0.50, DV −4.6; no angle) structures, were infused via Hamilton syringes. RetroBeads were intended to be used in combination with c-Fos IR to study neurocircuitry activated in response to binge-like drinking. However, since RetroBeads failed to exhibit measurable retrograde labeling these data were not quantified and are not described further. Following surgery conclusion, animals received topical analgesic cream containing Lidocaine and Prilocaine (25mg/g of each; Akorn Pharmaceuticals, Gurnee, IL). Subjects recovered for two weeks before undergoing testing (i.e., age at testing onset = 9 – 11 weeks). N=15 mice consumed only tap water during DID while n=15 consumed 20% ethanol. We used a larger sample size in this cohort relative to the surgery-naïve cohort described below as we anticipated loss of subjects due to missed RetroBead placement, but since we abandoned Retrobead assessment there was no need to remove animals.

Surgery-naïve cohort

20 mice never received surgery or anesthesia. Testing began 3 weeks after arriving to the UNC vivarium (i.e., age at testing onset = 9 – 11 weeks), approximately the same age that testing begin in the surgery cohort above. N=5 mice consumed only tap water while n=15 mice consumed 20% ethanol. Relative to water-consuming controls, we used a larger sample size in the 20% ethanol subset in anticipation of some animals failing to achieve binge-equivalent levels of intake.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were sacrificed 30 minutes after the 2-hour consumption test (i.e., 26–28 min post-tail blood collection). We chose this time point because maximal c-Fos expression typically emerges 90 to 120 minutes after experimental manipulations, though detectable c-Fos induction can occur 30 min post-manipulation, (Cullinan et al., 1995, Barros et al., 2015), and we wanted to limit the impact of blood sample manipulations on c-Fos expression.

Mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 3 minutes followed immediately by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; P6148, Sigma-Aldrich) for 7 minutes using a Masterflex L/S perfusion pump (catalogue #7200-12, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). Brains were collected and postfixed in approximately 15 mL 4% PFA for 24 h. Next, brains were cryoprotected in approximately 15 mL PBS solution containing 20% sucrose and 0.01% sodium azide (catalogue #S2002, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Brains were sectioned into 40 μm slices via vibratome (model VT1000 S, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Tissue was placed in cryopreserve and stored in a −20° freezer for later retrieval.

Sections underwent three 30 s rinses prior to overnight incubation in rabbit anti-cFos (catalogue #sc-52, lot# D0512, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), diluted 1:20,000 in PBS with 0.25% Triton-X (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 0.01% sodium azide (D5637, Sigma-Aldrich). Following two 30 s rinses, sections incubated for 30 min in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit secondary (1:1k; code #711-065-152, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:1000 in PBS. Sections underwent four additional rinses before incubating for 1 h in Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:1000 in PBS. Sections rinsed twice before exposure to PBS containing 0.05% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate (DAB; catalogue #D5637, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.05% ammonium nickel (II) sulfate hexahydrate (catalogue #A-1827, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide. The stain was terminated via rinses in PBS containing 0.01% sodium azide. Tissue obtained from surgery-exposed mice then underwent a second stain, with sections placed into a 1:20,000 dilution of sheep anti-TH (catalogue #AB1542, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). TH staining procedures were identical to c-Fos staining with the exceptions that the secondary step utilized donkey anti-sheep (1:1k; code #713-065-147, Jackson Immunoresearch) and nickel was omitted during the DAB step. For some regions, missing or partial sections further limited the number of animals in subsets of analyses.

Data Analyses

Brain region identification was based upon coordinates established in The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates atlas (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Counts represent the average of bilateral IR within 2 – 3 tissue slices per brain region for each animal. Slices were matched to images in the atlas corresponding to AP position relative to bregma (dBNST & vBNST: +0.38, +0.26, +0.14; CeA & BLA: −1.06, −1.34, −1.58; PVA (paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, anterior): −0.22, −0.46, −0.58; PVT (paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus): −1.22, −1.46, −1.82; EW: −3.4, −3.64, −3.8; LH (lateral hypothalamus): −1.22, −1.34, −1.46; LC: −5.34, −5.4, −5.52; lPBn: −5.2, −5.34; A2: −7.32, −7.48, −7.56). Despite performing TH/c-Fos IHC in the surgery cohort, we did not quantify TH/c-Fos co-expression in the VTA due to overwhelming TH staining and weak c-Fos expression in this region, regrettably obstructing co-localization efforts. Brain regions from one water-consuming control animal (mouse 1) in the DID-surgery cohort were photomicrographed and encircled in Adobe Illustrator (San Jose, CA) based upon boundaries established in the brain atlas at each level of AP listed above. To maintain consistent boundary identification of brain regions across animals, experimenter-encircled boundaries from mouse 1 were overlayed with all other mice. Due to unequal variances between groups in 3 of the brain regions examined (as indicated by significant Brown-Forsythe tests), non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess group differences in IR in all regions to maintain consistency of statistical methods. Dunn’s posthoc analysis was used when appropriate. All counts were performed by an individual blind to experimental conditions and are labeled in figures as median (black bars) and individual data points. Unpaired t-tests were used to assess BEC and ethanol consumption and are represented in text as mean ± standard error. Analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Comparison of c-Fos IR among mice with surgery experience

On test day, 8 (53%) ethanol-consuming mice exceeded the criteria for a binge episode (80 mg/dl BEC) with a mean ethanol consumption of 3.98 ± 0.17 g/kg and mean BEC of 121.63 ± 9.75 mg/dl (“≥ 80 mg/dl” group, Fig. 1 & 2). 7 DID-surgery mice failed to obtain BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl (“< 80 mg/dl” group, Fig. 1 & 2; consumption: 2.00 ± 0.29 g/kg; BEC: 40.23 ± 9.23 mg/dl). Ethanol consumption [t(13) = 6.097; p < 0.01] and BECs [t(13) = 6.012; p < 0.01] were significantly different between groups.

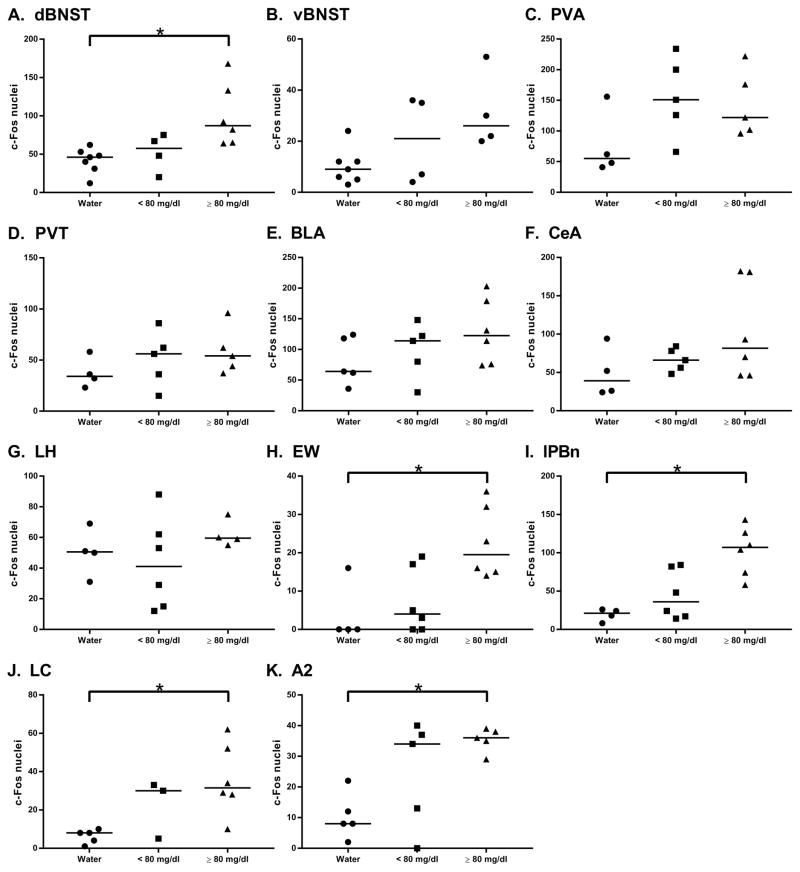

Figure 1.

C-Fos IR among surgery-exposed mice following one DID cycle. Relative to water-consuming controls, mice that consume enough ethanol (20%; 2 hr DID test day) to achieve or exceed binge-equivalent BECs (≥80 mg/dl) exhibit significant site-specific increases in c-Fos in A) dorsal bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (dBNST); H) Edinger-Westphal nucleus (EW); I) lateral parabrachial nucleus (lPBn); J) locus coeruleus (LC); and K) A2 subregion of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). Mice that failed to achieve binge-equivalent BECs are labeled as “< 80 mg/dl.” All values reflect bilateral counts and are represented as median (bar) and individual data points. * signifies p < 0.05.

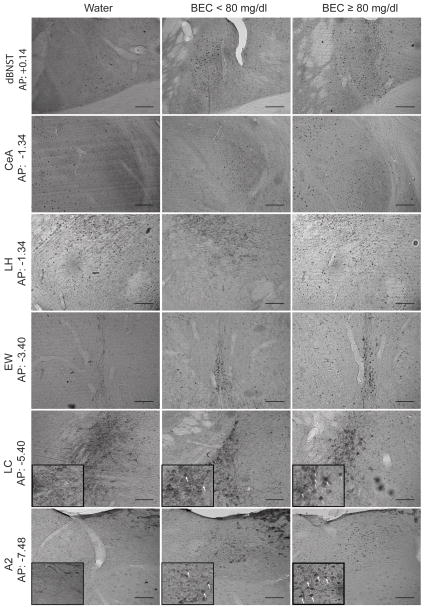

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs from brain regions where significant c-Fos differences were observed in mice with a history of surgery experience. dBNST, top row; CeA, second row from top; LH, third row from top; EW, third row from bottom; LC, second row from bottom; A2, bottom row. AP coordinates indicate approximate image locations according to The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Images at 20x magnification. Scale bars denote 0.1 mm.

Kruskal-Wallis tests indicated that mice exceeding the 80 mg/dl BEC binge threshold displayed significantly greater c-Fos-positive nuclei in the dBNST [Χ2(3) = 6.353, p < 0.05, ε2 = 0.42; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 1a; Fig. 2, top row], EW [Χ2(3) = 10.53, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.59; Dunn’s p < 0.01; Fig. 1h; Fig. 2, third row from bottom], LC [Χ2(3) = 9.645, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.54; Dunn’s p < 0.01; Fig. 1j; Fig. 2, second row from bottom], and A2 [Χ2 (3) = 11.45, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.82; Dunn’s p < 0.01; Fig. 1k; Fig. 2, bottom row] relative to water-consuming controls, while mice with BECs below 80 mg/dl did not exhibit c-Fos IR significantly different from controls across these regions. Interestingly, in the CeA, c-Fos IR was increased in both the < 80 mg/dl and ≥ 80 mg/dl groups relative to the water drinking control group [Χ2(3) = 10.56, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.75; Dunn’s p < 0.05 (water vs. < 80 mg/dl) and p < 0.05 (water vs. ≥ 80 mg/dl); Fig. 1f; Fig. 2, second row from top], suggesting that ethanol consumption activates this region regardless of BEC achieved. Mice obtaining BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl displayed significantly greater c-Fos IR in the LH [Χ2(3) = 6.962, p < 0.05, ε2 = 0.63; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 1g; Fig. 2, third row from top], but only when compared to the < 80 mg/dl group. Kruskal-Wallis tests failed to detect significant c-Fos IR differences in vBNST [Χ2(3) = 2.892, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.19; Fig. 1b], PVA [Χ2(3) = 0.274, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.02; Fig. 1c], PVT [Χ2(3) = 4.835, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.35; Fig. 1d], BLA [Χ2(3) = 1.522, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.12; Fig. 1e], and lPBn [Χ2(3) = 5.352, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.36; Fig. 1i]. For both the A2 and LC, TH/c-Fos co-expression was greatest among mice exceeding the 80 mg/dl binge threshold (A2: 35–40%; LC: 40–50%; Fig. 2, second row from bottom and bottom row). Co-expression was comparatively lower among mice that failed to achieve the 80 mg/dl binge threshold (A2: 10–15%; LC: 15–20%, Fig. 2, second row from bottom and bottom row), and co-expression was essentially non-existent among water-consuming mice (Fig. 2, second row from bottom and bottom row).

Comparison of c-Fos IR among mice without surgery experience

Among ethanol-consumers, 7 (47%) achieved BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl with a mean ethanol consumption of 3.16 ± 0.19 g/kg and mean BEC of 114.67 ± 7.62 mg/dl (“ ≥80 mg/dl” group, Fig. 3 & 4). 8 DID-non-surgery mice failed to obtain BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl (“< 80 mg/dl” group, Fig. 3 & 4; consumption: 1.99 ± 0.21 g/kg; BEC: 23.49 ± 8.97 mg/dl). BECs were significantly different [t(13) = 7.624; p < 0.01], and mice that failed to achieve binge-equivalent BECs consumed significantly less ethanol than mice that exceeded the 80 mg/dl binge threshold [t(13) = 4.054; p < 0.01].

Figure 3.

C-Fos IR among surgery-naive mice following one DID cycle. Relative to water-consuming controls, mice that consume enough ethanol (20%; 2 hr DID test day) to achieve or exceed binge-equivalent BECs (≥80 mg/dl) exhibit significant site-specific increases in c-Fos in A) dBNST; H) EW; J) LC; and K) A2 of the NTS. F) C-Fos in the central amygdala (CeA) is increased among mice that consume ethanol relative to water-consuming controls. G) C-Fos in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) is significantly increased among mice that binged relative to mice that failed to achieve binge-equivalent BECs (< 80 mg/dl), but neither condition was significantly different from water consumption-elicited c-Fos. All values reflect bilateral counts and are represented as median (bar) and individual data points. * signifies p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs from brain regions where significant c-Fos differences were observed in mice without a history of surgery experience. dBNST, top row; EW, second row from top; lPBn, middle row; LC, second row from bottom; A2, bottom row. AP coordinates indicate approximate image locations according to The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). Images at 20x magnification, with scale bars denoting 0.1 mm. Inset images in second row from bottom and bottom row were taken at 40x magnification, with white arrows denoting TH/c-Fos double labeling.

Relative to water-consuming controls, mice with BECs exceeding 80 mg/dl exhibited significantly greater c-Fos IR in the dBNST [Χ2(3) = 9.504, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.59; Dunn’s p < 0.01; Fig. 3a; Fig. 4, top row], EW [Χ2(3) = 6.272, p < 0.05, ε2 = 0.42; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 3h; Fig. 4, second row from top], lPBn [Χ2(3) = 8.65, p < 0.01, ε2 = 0.58; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 3i;, Fig. 4, middle row], LC [Χ2(3) = 7.117, p < 0.05, ε2 = 0.55; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 3j; Fig. 4, second row from bottom], and A2 [Χ2(3) = 6.271, p < 0.05, ε2 = 0.45; Dunn’s p < 0.05; Fig. 3k; Fig. 4, bottom row]. We failed to observe statistically significant differences in cFos IR across conditions in the vBNST [Χ2(3) = 4.336, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.31; Fig. 3b], PVA [Χ2(3) = 4.063, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.31; Fig. 3c], PVT [Χ2(3) = 2.538, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.20; Fig. 3d], BLA [Χ2(3) = 2.328, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.16; Fig. 3e], CeA [Χ2(3) = 1.938, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.14; Fig. 3f], and LH [Χ2(3) = 2.024, p > 0.05, ε2 = 0.16; Fig. 3g].

Discussion

While there have been numerous studies that have assessed c-Fos IR in response to ethanol consumption and administration, to date there has been no assessment of brain c-Fos IR using DID procedures in mice. Since different procedures induce different patterns of c-Fos IR, the present work provides novel information on brain region activation in response to binge-like ethanol drinking specifically stemming from DID procedures. Additionally, we sought to make qualitative comparisons regarding ethanol-induced c-Fos IR in animals with and without a history of intracranial surgery, in light of recent evidence that exposure to an anesthetic drug can impact c-Fos IR (Smith et al. 2016) and as many studies that employ DID procedures entail intracranial surgery prior to assessment of binge-like ethanol drinking. The major findings were that 1) ethanol ingestion associated with binge-equivalent BECs site-specifically increased c-Fos IR relative to controls; 2) brain regions exhibiting significantly elevated c-Fos IR were overlapping, though not identical, across surgery conditions; 3) in most brain regions, binge-like ethanol drinking that generated BECs of 80 mg/dl or greater caused significantly greater c-Fos IR relative to water drinking controls while drinking ethanol that generated BECs below 80 mg/dl failed to induce significant c-Fos IR relative to water drinking controls.

Significant binge-induced increases of c-Fos IR were similar between surgery conditions in most brain regions. We found that achieving BECs greater than or equal to 80 mg/dl significantly increased c-Fos IR in the dBNST, EW, LC, and A2 relative to water-consuming controls in both surgery-exposed and surgery-naïve studies. On the other hand, binge-induced c-Fos IR in the lPBn was only evident in the surgery-naïve group, and binge-induced c-Fos IR in the LH and CeA were only evident in mice with a prior history of surgery. Interestingly, ethanol drinking that failed to promote binge-like BEC levels also induced c-Fos IR in the CeA of animals with a prior surgery. Our results are largely consistent with and extend previous literature showing that acute binge intoxication in rats via i.p. injection increases c-Fos IR in the BNST, CeA, EW, LC, PBn, and A2 (Chang et al., 1995, Thiele et al., 1996, Ryabinin et al., 1997, Thiele et al., 2000, Knapp et al., 2001, Sharko et al., 2016).

Previous studies have shown that voluntary ethanol consumption in limited access sessions, wherein water-restricted rodents were allotted 30 min to consume either 10% ethanol (2.5 hr into dark cycle; Sharpe et al., 2005), 10% ethanol/10% sucrose (testing in light cycle; Bachtell et al., 1999), or 10% ethanol and 10% ethanol/0.2% saccharin solutions (7 hr into dark cycle; Weitemier et al., 2001) solutions, increase Fos IR in the nucleus accumbens core (AcbC), the medial posterioventral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeMPV; Bachtell et al., 1999), and the EW (Bachtell et al., 1999, Weitemier et al., 2001, Sharpe et al., 2005). Similarly, we found that a single binge-like drinking cycle with DID procedures increased c-Fos IR in the CeA among surgery-exposed mice, and in the EW among both surgery conditions. However, our results showed that binge-like ethanol drinking stemming from DID procedures caused c-Fos IR in the BNST and PVT, which were not detected with 30 min limited access procedures, and we did not find binge-induced c-Fos in the AcbC (not quantified due to the lack of expression) and CeMPV. Interestingly, in a study with C57BL/6J mice that used a 10% ethanol/10% sucrose solution which promoted binge-like drinking (~2.9 g/kg of ethanol) and associated BECs (~250 mg/dL) over a 30-minute test, there was no evidence of increased c-Fos IR in areas of the amygdala and reduced c-Fos IR in the LH relative to water-drinking mice, both observations that are inconsistent with our findings. Similar to our results though, they did find increased c-Fos IR in the EW (Ryabinin et al., 2003). Numerous procedural differences between the studies described above and our manipulations 1) reinforce the idea that ethanol-induced c-Fos IR is procedure-specific, and 2) highlight the novelty of the present work which reveals neuronal activity specific to DID procedures, which will better inform studies that adapt this paradigm.

Because surgery-naïve and surgery-exposed studies were performed at separate times, we were unable to make direct quantitative comparisons of c-Fos IR between studies. Qualitatively, we observed differences in CeA, LH, and lPBn c-Fos IR between surgery conditions. There are numerous factors that could contribute to differences between surgery conditions, including administration of anesthetic drugs, stress, engagement of the immune system in response to surgery, RetroBead presence in surgery-exposed mice, and accordingly, we are unable to identify the specific variables that may have promoted differences in c-Fos IR between our studies. However, these observations suggest that caution is necessary when interpreting studies that assess ethanol-induced c-Fos IR, or other measures of cellular activity, in animals with a prior history of surgery.

Because we found robust c-Fos IR in the A2 and LC in both surgery conditions using DID procedures, we further assessed TH and c-Fos co-expression in these noradrenergic nuclei. Among surgery-exposed mice, we found that voluntary water consumption produced near-zero co-expression in both structures. Conversely, the percentage of co-expression was elevated among animals that achieved binge-like BEC levels (A2: 35–40%; LC: 40–50%). These expression patterns are comparable with previously reported findings in male rats, where i.p. ethanol injections elicited ~65–75% and ~35–60% co-expression in the A2 and LC, respectively (Thiele et al., 2000). While caution is necessary when making between-species comparisons, i.p. injection of ethanol appears to promote great c-Fos/TH co-expression in the A2 relative to binge-like ethanol drinking. The LC innervates numerous brain regions including the orbitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, LH, amygdala, and VTA, among others (Foote et al., 1983, Chandler et al., 2014), while the A2 innervates regions that include the BNST, accumbens shell, LH, and VTA (Delfs et al., 2000, Smith and Aston-Jones, 2008, Mejias-Aponte et al., 2009). Given the elevated levels of TH/c-Fos co-expression in A2 and LC following binge-like ethanol consumption, as well as increased c-Fos in regions innervated by the A2 and/or LC (LH, BNST, CeA), noradrenergic circuitry may play an important role in modulating ethanol consumption associated with DID procedures. Accordingly, our lab is investigating possible involvement of noradrenergic circuitry in modulation of voluntary binge-like ethanol consumption.

An examination of our c-Fos IR data indicates that in many brain regions c-Fos IR was relatively high under baseline water drinking. An inherent aspect to the DID procedure is that behavioral assessment is performed during the dark cycle, when mice are more active and consume the majority of their daily food and water. In rats, others have demonstrated that c-Fos mRNA expression oscillates depending on time of day, with increased c-Fos activity occurring at night and weak activity during rest hours (Grassi-Zucconi et al., 1993). Moreover, light/dark exposure can site-specifically influence c-Fos IR in the rat brain, with the “lights-on” phase increasing c-Fos IR presence in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (Aronin et al., 1990) and the “lights-off” phase increasing c-Fos IR in various regions including the PVT, magnocellular paraventricular nuclei, and dorsomedial nuclei (Choi et al., 1998). Interestingly, in reviewing the literature involving experimenter-administered ethanol to model binge-like exposure, this work was almost exclusively conducted in the lights-on portion of rodent light cycle. Thus, higher-than-anticipated basal c-Fos IR in the control conditions of our studies may potentially be a product of collecting measures during the dark cycle. Additionally, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that stress associated with blood sampling procedures contributed to high baseline levels of c-Fos IR, but since blood samples were collected in all groups, including the water drinking group, a potential effect of stress from blood on c-Fos IR would not have biased group differences.

Finally, we must note that our procedures were performed in males exclusively. Adult female C57BL/6J mice have been reported to voluntarily consume significantly more ethanol (g/kg) than male counterparts in intermittent 24-h access paradigms (Hwa et al., 2011), under conditions of food or water deprivation (Middaugh and Kelley, 1999), and in two-bottle choice paradigms with 2-h limited access sessions (Vetter-O’Hagen et al., 2009) or continuous access (Yoneyama et al., 2008). Thus, future studies should investigate potential sex differences in binge-induced neuronal activation stemming from DID procedures.

Taken together, our results indicate that a single 4-day binge-like ethanol drinking session with DID procedures region-specifically activates c-Fos IR in brain areas implicated in neurobiological responses to ethanol and ethanol drinking, specifically the dBNST, EW, LC, and A2. Surgery-naïve and surgery-exposed mice displayed significantly elevated c-Fos IR across largely overlapping regions (dBNST, EW, LC, A2), though differences between studies highlight the need for caution when interpreting data assessing neuronal activity when subjects have a prior history of surgery. Altogether, this work provides insight for future studies aimed at identifying brain regions and circuitry involved in modulation of binge-like ethanol drinking, particularly those employing DID procedures.

Highlights.

Binge-induced c-Fos with “drinking in the dark” (DID) procedures was assessed.

Groups with and without prior intracranial surgery were compared.

Differences between surgery condition suggest a point of caution for c-Fos studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants AA013573, AA015148, and AA022048.

Abbreviations

- A2

A2 region of the NTS

- AcbC

nucleus accumbens core

- BEC

blood ethanol concentration

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CeA

central amygdala

- CeMPV

medial posterioventral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala

- CRF

corticotropin releasing factor

- dBNST

dorsal bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- DID

“drinking-in-the-dark” paradigm

- EW

Edinger-Westphal nucleus

- hr

hour

- i.p

intraperitoneal injection

- IR

immunoreactivity

- LC

locus coeruleus

- LH

lateral hypothalamus

- lPBn

lateral parabrachial nucleus

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PVA

paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, anterior

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus

- PVT

paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- vBNST

ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albrechet-Souza L, Hwa LS, Han X, Zhang EY, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Corticotropin Releasing Factor Binding Protein and CRF2 Receptors in the Ventral Tegmental Area: Modulation of Ethanol Binge Drinking in C57BL/6J Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:1609–1618. doi: 10.1111/acer.12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronin N, Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Schwartz WJ. Light regulates expression of a Fos-related protein in rat suprachiasmatic nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5959–5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Wang YM, Freeman P, Risinger FO, Ryabinin AE. Alcohol drinking produces brain region-selective changes in expression of inducible transcription factors. Brain Res. 1999;847:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros VN, Mundim M, Galindo LT, Bittencourt S, Porcionatto M, Mello LE. The pattern of c-Fos expression and its refractory period in the brain of rats and monkeys. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:72. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Smith RJ, Toalston JE, Franklin KM, McBride WJ. Modeling binge-like ethanol drinking by peri-adolescent and adult P rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DJ, Gao WJ, Waterhouse BD. Heterogeneous organization of the locus coeruleus projections to prefrontal and motor cortices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6816–6821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320827111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SL, Patel NA, Romero AA. Activation and desensitization of Fos immunoreactivity in the rat brain following ethanol administration. Brain Res. 1995;679:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00210-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Wong LS, Yamat C, Dallman MF. Hypothalamic ventromedial nuclei amplify circadian rhythms: do they contain a food-entrained endogenous oscillator? J Neurosci. 1998;18:3843–3852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Battaglia DF, Akil H, Watson SJ. Pattern and time course of immediate early gene expression in rat brain following acute stress. Neuroscience. 1995;64:477–505. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T, Morgan JI. Fos: an immediate-early transcription factor in neurons. J Neurobiol. 1995;26:403–412. doi: 10.1002/neu.480260312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfs JM, Zhu Y, Druhan JP, Aston-Jones G. Noradrenaline in the ventral forebrain is critical for opiate withdrawal-induced aversion. Nature. 2000;403:430–434. doi: 10.1038/35000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabio MC, March SM, Molina JC, Nizhnikov ME, Spear NE, Pautassi RM. Prenatal ethanol exposure increases ethanol intake and reduces c-Fos expression in infralimbic cortex of adolescent rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103:842–852. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabio MC, Vivas LM, Pautassi RM. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters ethanol-induced Fos immunoreactivity and dopaminergic activity in the mesocorticolimbic pathway of the adolescent brain. Neuroscience. 2015;301:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Bloom FE, Aston-Jones G. Nucleus locus ceruleus: new evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:844–914. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.3.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi-Zucconi G, Menegazzi M, De Prati AC, Bassetti A, Montagnese P, Mandile P, Cosi C, Bentivoglio M. c-fos mRNA is spontaneously induced in the rat brain during the activity period of the circadian cycle. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1071–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgate JY, Shariff M, Mu EW, Bartlett S. A Rat Drinking in the Dark Model for Studying Ethanol and Sucrose Consumption. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:29. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa LS, Chu A, Levinson SA, Kayyali TM, DeBold JF, Miczek KA. Persistent escalation of alcohol drinking in C57BL/6J mice with intermittent access to 20% ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1938–1947. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DJ, Braun CJ, Duncan GE, Qian Y, Fernandes A, Crews FT, Breese GR. Regional specificity of ethanol and NMDA action in brain revealed with FOS-like immunohistochemistry and differential routes of drug administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1662–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larraga A, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM. Nicotine Increases Alcohol Intake in Adolescent Male Rats. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:25. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Craddock Z, Rivier C. Brain stem catecholamines circuitry: activation by alcohol and role in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to this drug. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leriche M, Mendez M, Zimmer L, Berod A. Acute ethanol induces Fos in GABAergic and non-GABAergic forebrain neurons: a double-labeling study in the medial prefrontal cortex and extended amygdala. Neuroscience. 2008;153:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Cheng Y, Bian W, Liu X, Zhang C, Ye JH. Region-specific induction of FosB/DeltaFosB by voluntary alcohol intake: effects of naltrexone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1742–1750. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery-Gionta EG, Navarro M, Li C, Pleil KE, Rinker JA, Cox BR, Sprow GM, Kash TL, Thiele TE. Corticotropin releasing factor signaling in the central amygdala is recruited during binge-like ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3405–3413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6256-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejias-Aponte CA, Drouin C, Aston-Jones G. Adrenergic and noradrenergic innervation of the midbrain ventral tegmental area and retrorubral field: prominent inputs from medullary homeostatic centers. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3613–3626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4632-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh LD, Kelley BM. Operant ethanol reward in C57BL/6 mice: influence of gender and procedural variables. Alcohol. 1999;17:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Olney JJ, Burnham NW, Mazzone CM, Lowery-Gionta EG, Pleil KE, Kash TL, Thiele TE. Lateral Hypothalamus GABAergic Neurons Modulate Consummatory Behaviors Regardless of the Caloric Content or Biological Relevance of the Consumed Stimuli. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1505–1512. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JJ, Navarro M, Thiele TE. Binge-like consumption of ethanol and other salient reinforcers is blocked by orexin-1 receptor inhibition and leads to a reduction of hypothalamic orexin immunoreactivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:21–29. doi: 10.1111/acer.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JJ, Navarro M, Thiele TE. The Role of Orexin Signaling in the Ventral Tegmental Area and Central Amygdala in Modulating Binge-Like Ethanol Drinking Behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:551–561. doi: 10.1111/acer.13336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleil KE, Rinker JA, Lowery-Gionta EG, Mazzone CM, McCall NM, Kendra AM, Olson DP, Lowell BB, Grant KA, Thiele TE, Kash TL. NPY signaling inhibits extended amygdala CRF neurons to suppress binge alcohol drinking. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nn.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Ford MM, Yu CH, Brown LL, Finn DA, Garland T, Jr, Crabbe JC. Mouse inbred strain differences in ethanol drinking to intoxication. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker JA, Marshall SA, Mazzone CM, Lowery-Gionta EG, Gulati V, Pleil KE, Kash TL, Navarro M, Thiele TE. Extended Amygdala to Ventral Tegmental Area Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Circuit Controls Binge Ethanol Intake. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:930–940. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Criado JR, Henriksen SJ, Bloom FE, Wilson MC. Differential sensitivity of c-Fos expression in hippocampus and other brain regions to moderate and low doses of alcohol. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Galvan-Rosas A, Bachtell RK, Risinger FO. High alcohol/sucrose consumption during dark circadian phase in C57BL/6J mice: involvement of hippocampus, lateral septum and urocortin-positive cells of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:296–305. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajja RK, Rahman S. Cytisine modulates chronic voluntary ethanol consumption and ethanol-induced striatal up-regulation of DeltaFosB in mice. Alcohol. 2013;47:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharko AC, Kaigler KF, Fadel JR, Wilson MA. Ethanol-induced anxiolysis and neuronal activation in the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Alcohol. 2016;50:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AL, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Ataxia and c-Fos expression in mice drinking ethanol in a limited access session. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1419–1426. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000174746.64499.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Aston-Jones G. Noradrenergic transmission in the extended amygdala: role in increased drug-seeking and relapse during protracted drug abstinence. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:43–61. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprow GM, Thiele TE. The neurobiology of binge-like ethanol drinking: evidence from rodent models. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Cubero I, van Dijk G, Mediavilla C, Bernstein IL. Ethanol-induced c-fos expression in catecholamine- and neuropeptide Y-producing neurons in rat brainstem. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:802–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Navarro M. “Drinking in the dark” (DID) procedures: a model of binge-like ethanol drinking in non-dependent mice. Alcohol. 2014;48:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Roitman MF, Bernstein IL. c-Fos induction in rat brainstem in response to ethanol- and lithium chloride-induced conditioned taste aversions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek VF, Ryabinin AE. Expression of c-Fos in the mouse Edinger-Westphal nucleus following ethanol administration is not secondary to hypothermia or stress. Brain Res. 2005;1063:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter-O’Hagen C, Varlinskaya E, Spear L. Sex differences in ethanol intake and sensitivity to aversive effects during adolescence and adulthood. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:547–554. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitemier AZ, Woerner A, Backstrom P, Hyytia P, Ryabinin AE. Expression of c-Fos in Alko alcohol rats responding for ethanol in an operant paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:704–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama N, Crabbe JC, Ford MM, Murillo A, Finn DA. Voluntary ethanol consumption in 22 inbred mouse strains. Alcohol. 2008;42:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]